What Exactly Is an Art Movement? A Deep Dive into Art's Grand Chapters

Ever wondered why art seems to evolve in 'movements'? Join me as we explore what defines an art movement, why they emerge, and how understanding them unlocks a richer appreciation for art history and contemporary creation. It's more personal than you think!

What Exactly Is an Art Movement? A Deep Dive into Art's Grand Chapters – Your Ultimate Guide

I've always been captivated by the human impulse to categorize, to weave order from the beautiful chaos of existence. We label phenomena, group shared ideas, styles, and epochs – and art, in its boundless forms, is no exception. Standing before a masterpiece, or simply scrolling through a digital gallery, you're bound to encounter terms like “Cubism,” “Surrealism,” and “Impressionism.” For many, these can feel like a secret language, a series of enigmatic buzzwords that require a decoder ring or a hidden handshake to truly unlock their meaning and appreciate their enduring relevance in our world today. And let me tell you, as an artist, understanding these movements has been transformative for my own practice.

But when we peel back the layers of these familiar labels, what truly defines these monumental shifts in artistic expression? What are the underlying currents that propel their emergence? What fuels their distinct philosophies, and how do they continue to resonate, inspire, and provoke the art we see and create today – including, of course, the abstract explorations I pursue right here at ZenMuseum? These are not mere academic questions for me; they are the very inquiries that ignite my artistic journey, and they are precisely what we'll unpack, explore, and ultimately illuminate together in this comprehensive guide. In fact, my aim with this article is to create the ultimate, most engaging, and most useful resource on 'what is an art movement' that you'll find anywhere.

Well, I've spent a fair bit of time pondering this – both as an artist and as someone who simply loves diving deep into culture – and I've come to realize that understanding what an art movement is isn't just about memorizing dates and names. It's about recognizing the very human impulse to innovate, to react, to rebel, and to find kinship in shared creative visions. For me, it's about seeing art history not as a series of isolated masterpieces, but as an ongoing, vibrant conversation, a grand dialogue across centuries and continents. It's a way to understand the pulse of humanity through its visual expression, and a powerful lens through which to view our own creative impulses.

In this guide, my aim is to unpack the entire concept for you, making sense of the labels and showing you why they matter – not just for art historians, but for anyone who appreciates creativity, including those of us who make abstract art today. We'll delve into the very fabric of what makes a movement, exploring its origins, characteristics, and enduring impact. I want to share my personal journey through understanding these grand chapters of art, and how they continue to resonate with my own practice as an artist. This isn't just about history; it's about finding echoes of past innovation in the art you see and create right now.

Unpacking the Idea: What Is an Art Movement? The Core Elements

So, at its core, an art movement is far more than just a fleeting trend; it's a profound and significant wave in the vast, ever-shifting ocean of art history. What defines it? A shared philosophy or a unifying goal, typically embraced by a collective of artists during a discernible period. It’s that exhilarating moment when a constellation of creative minds, often connecting in physical spaces like Parisian salons or Viennese coffee houses, but increasingly through publications and shared ideologies, begin to perceive, interpret, and express the world in a remarkably similar, yet utterly revolutionary, way. Crucially, these movements frequently emerge as a direct response to what came before – a deliberate challenge to the aesthetic and conceptual status quo, or a fresh, compelling reinterpretation of existing realities.

It's this collective shift in perspective, a shared artistic language that defines an era, that truly fascinates me. It's not just a gradual evolution, but often a deliberate rupture with established norms, a bold declaration of a new way of seeing and expressing the world around us. Think of it as a cultural paradigm shift, a moment when the artistic conversation takes a sharp, exhilarating turn. It’s this shared artistic language – a new grammar of forms, colors, and concepts – that allows us to group artists across continents and decades. This language speaks volumes about the historical moment from which it emerged.

I like to think of it like this: it’s not just a random collection of artists doing their own individual thing, each isolated in their studio. No, there's a powerful, shared intellectual and aesthetic underpinning that binds them, creating a collective identity that transcends individual genius. Imagine a band forming: each musician brings their unique talent and perspective, but they coalesce around a unified sound, a shared message, and a particular style that truly sets them apart. They define their genre, often through a deliberate manifesto or a series of provocative exhibitions. Then, other artists either pick up on this new 'sound,' evolving it further, or they react against it, pushing the artistic conversation into entirely new territories. The same dynamic, the same exhilarating push and pull, happens in art, just with paint, clay, digital screens, and performance instead of guitars and drums. And crucially, this shared language isn't just about aesthetics; it often carries profound philosophical, social, or political messages.

Beyond the analogy, this 'shared intellectual and aesthetic underpinning' manifests in wonderfully tangible ways. We see it in recurrent motifs that echo across canvases, in revolutionary techniques that break with tradition, in the adoption of specific materials that become emblematic of an entire movement. It's not just about what is depicted, but how it is depicted, and the deeper philosophical currents that give it purpose. This collective, cohesive identity allows us, centuries later, to look back and trace these distinct, vibrant chapters in humanity's ongoing creative journey.

For me, the beauty of an art movement lies in its collective spirit. It’s a powerful testament to how shared ideas can ignite a blaze of creativity, pushing boundaries and challenging conventions, ultimately shaping how we see the world. It’s an almost alchemical process where individual talents coalesce into something far greater.

The Human Need to Categorize: Why Movements Matter

Why do we even bother with these labels, though? Is it just academic neatness? I don't think so. I believe it stems from a deeply human need to understand, to organize, and to find meaning in the vast, often chaotic, landscape of human expression. For me, it's about creating mental landmarks in a sprawling territory. Categorizing art into movements helps us:

- Identify Patterns: It allows us to discern recurring themes, techniques, and philosophies across seemingly disparate artists and regions. We start seeing the invisible threads that connect a work from Paris to one from New York, simply because they share a conceptual or aesthetic DNA.

- Trace Influence and Evolution: Movements are like stepping stones across the river of time. They allow us to track how one artistic idea leads to another, how artists consciously learn from, subtly reinterpret, or powerfully rebel against their predecessors. It's the story of artistic dialogue, played out on a grand scale.

- Understand Historical and Social Context: Art never exists in a vacuum. Movements are often deeply intertwined with their historical, social, political, and even economic environments. Understanding a movement helps us understand the era that birthed it – its anxieties, its aspirations, its upheavals. It's a visual history lesson.

- Appreciate Innovation and Radicalism: By clearly seeing what came before, we can truly grasp the radical departures, the groundbreaking ideas, and the audacious innovations that define new movements. What might seem ordinary to us today was once revolutionary, and understanding its context reveals its true audacity.

- Facilitate Discussion and Critical Analysis: Having a common vocabulary provides a shared language, allowing critics, historians, educators, and art lovers (like us!) to discuss, compare, and analyze art more effectively. It turns subjective appreciation into informed conversation.

- Preserve History and Legacy: Movements provide a vital framework for organizing, interpreting, and preserving the vast, often overwhelming, output of human creativity. This ensures that future generations can learn from, be inspired by, and continue the grand dialogue of art history.

- Deepen Personal Engagement: For me, these categories aren't restrictive; they're invitations. They spark curiosity, encouraging us to dive deeper, to find our own connections, and to discover what truly resonates with our individual sensibilities. They provide a roadmap for personal exploration within the art world.

Key Elements That Define an Art Movement

To help clarify, here's a look at the essential ingredients that typically go into the making of a recognized art movement.

Element | Description |

|---|---|

| Shared Vision | Artists within a movement often articulate a common philosophy, set of goals, or a unified approach to art-making. This isn't always a formal declaration, but a detectable shared sensibility, often captured in manifestos or collective statements. |

| Distinct Aesthetic | A recognizable visual language or set of techniques that defines the movement, a kind of visual "accent." Think of the intense, non-naturalistic colors of Fauvism or the fragmented planes and multiple perspectives of Cubism. |

| Group Identity | While individual artists are celebrated, the movement is characterized by a group or collective of artists who align with its principles. They often exhibit together, publish shared texts, or engage in rigorous discourse, fostering a sense of artistic kinship. |

| Defined Timeframe | Most movements have a discernible start, peak, and eventual decline or evolution into something new. This period can range from a few intense years to several decades, often coinciding with specific historical shifts. |

| Reactionary Nature | Many movements arise in direct opposition to, or as a reinterpretation of, previous artistic norms, academic traditions, or societal conditions. This 'push-and-pull' is a constant, dynamic force in art history, preventing stagnation. |

| Innovation | Art movements are almost always about pushing boundaries, introducing new materials, revolutionary techniques (like collage or readymades), novel subjects, or entirely new conceptual frameworks that were previously unexplored or considered unconventional. It's about breaking new ground. |

| Influence & Legacy | A truly impactful movement leaves an indelible mark, influencing subsequent generations of artists across different disciplines and shaping the broader trajectory of art history, even long after its active period. Its ideas continue to resonate. |

| Critical Dialogue | The emergence of a movement often sparks intense debate and discussion among critics, the public, and artists themselves. This dialogue, whether positive or negative, solidifies its place in the cultural consciousness and helps to define its meaning and impact. |

| Interdisciplinary Nature | Many significant movements extend beyond painting or sculpture, influencing literature, music, architecture, fashion, and design, reflecting a broader cultural shift. Think of how Art Nouveau embraced everything from posters to furniture. |

| Global Reach | While some movements are geographically concentrated, many influential ones eventually spread across national borders, adapting and inspiring artists in different cultural contexts, leading to global dialogues and new interpretations. |

It's fascinating how these elements combine, sometimes organically, sometimes through deliberate effort, to coalesce into something we later call a "movement." It’s often a messy, vibrant process, much like mixing paints on a palette, where new colors (ideas) emerge from unexpected combinations.

The Driving Forces: Why Do Art Movements Emerge? It's Not Just Random!

This is where it truly gets fascinating for me. Art movements don't simply materialize out of thin air; they are rarely a spontaneous, isolated combustion of creativity. Instead, I've come to understand them as extraordinarily sensitive cultural barometers, finely tuned to the prevailing zeitgeist, both reacting to and often actively shaping the world around them. They are born from a confluence of forces, much like how my own abstract works draw from a myriad of personal and societal influences. Here are a few things I've noticed consistently tend to spark these significant, often radical, shifts in artistic expression:

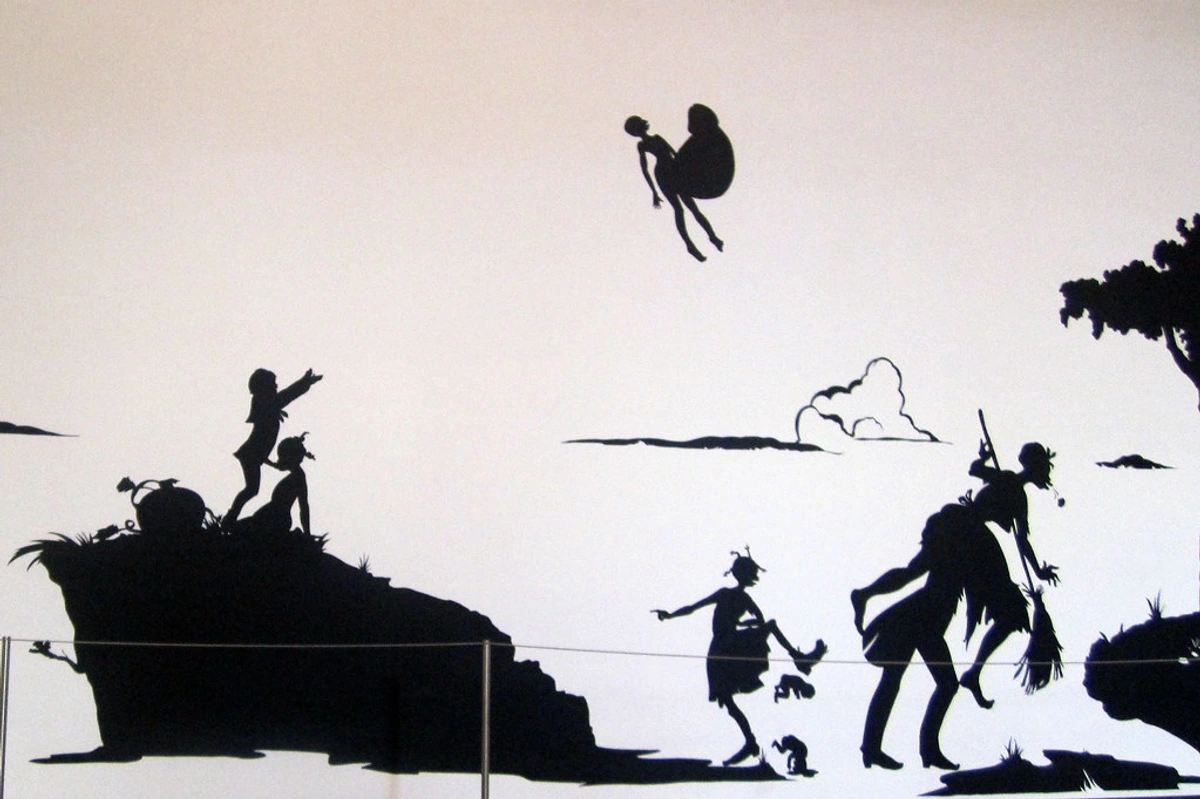

- Social and Political Upheaval: This is a huge one, a powerful catalyst. Major wars, revolutions, significant societal shifts, or even profound social injustices often lead artists to question existing norms, challenge power structures, and express new, often difficult, realities. Think, for instance, about how Dadaism (a movement I'll explore more deeply in future articles, and one often misunderstood for its playful absurdity) emerged as a furious, often nonsensical, response to the horrors and sheer irrationality of World War I – a direct artistic scream against a world gone mad. Art in these tumultuous times becomes a potent mirror reflecting the chaos, or perhaps more ambitiously, a hammer attempting to reshape its era. Consider also the politically charged Russian Avant-Garde movements like Constructivism and Suprematism, which arose directly from the fervor and idealism of the Russian Revolution, aiming to forge a new art for a new society, one built on radical new visual principles. Or, in a different vein, look at the powerful works of Kara Walker, whose silhouette installations grapple with the legacies of slavery and racial injustice in America, profoundly shaping contemporary discourse on history and identity by forcing us to confront uncomfortable truths. Even the decolonization movements of the mid-20th century profoundly influenced artistic expressions across continents, challenging Western-centric narratives and elevating indigenous perspectives, giving voice to previously marginalized stories. This dynamic continues today, as artists respond to climate change, digital surveillance, and global inequalities.

- Technological Advancements: Humanity's progress in technology almost always spills over into art, often revolutionizing how and what artists create. The invention of portable paint tubes directly influenced Impressionism, allowing artists to leave the studio and paint outdoors, capturing fleeting moments of light and color that were previously impossible. Photography, too, was a game-changer; it freed painting from its documentary role, pushing artists toward abstraction and exploring what only paint could do, challenging painters to delve into subjective experience rather than mere representation. More recently, digital tools have birthed entirely new forms of art and movements, such as various forms of digital art, net art, and even AI-generated art, each prompting new aesthetic considerations and philosophical debates about authorship and creativity. But these shifts aren't just about computers. Think about the advent of readily available tube paints in the 19th century, which directly influenced Impressionism by freeing artists from the studio to capture fleeting outdoor moments. The rise of photography, too, liberated painting from its purely documentary role, pushing artists towards abstraction and exploring what only paint could express. Even earlier, the invention of printing techniques dramatically altered how art and ideas could be disseminated, influencing everything from political caricatures to scientific illustrations, and later, the bold graphics of propaganda posters that became synonymous with early 20th-century avant-garde movements. Each new tool opens up a new realm of possibility, a fresh challenge to the creative mind.

- Philosophical and Scientific Shifts: New ways of thinking about humanity, the universe, or the subconscious can profoundly impact artistic expression, essentially reshaping the very lens through which artists perceive reality. Surrealism, for instance, was deeply influenced by Freud's theories on dreams and the unconscious mind, opening up a whole new realm of subject matter previously deemed off-limits or too irrational for serious art. The philosophical shift towards existentialism after World War II, for example, heavily influenced movements like Abstract Expressionism, reflecting a sense of angst, individualism, and a fervent search for meaning in a seemingly meaningless world. Similarly, advancements in understanding light and optics influenced movements like Op Art, which sought to explore perception itself, challenging the viewer's eye and mind. Even deeper, philosophical shifts such as Darwinism influenced movements like Realism and Naturalism, prompting artists to observe the world with a scientific eye, focusing on everyday life and unvarnished truth, often with a critical social commentary. Later, the revelations of quantum physics in the early 20th century, which shattered previous understandings of reality and introduced concepts of uncertainty and multiple perspectives, resonated with artists grappling with fragmented perspectives and the dissolution of traditional forms, indirectly fueling the rise of early abstract movements and the deconstruction seen in Cubism. These aren't just minor ripples; they are seismic shifts in how we understand existence, inevitably reflected in our art as artists grapple with profound questions about reality, truth, and human experience.

- Reaction Against Predecessors: This is a truly significant and recurring theme, a kind of artistic generational rebellion! Often, a new movement is born from a deep dissatisfaction with, or a deliberate rejection of, the established artistic order, a feeling that "we can do better," or simply "we must do something different." The Neoclassical movement, for example, reacted vehemently against the perceived frivolity, sensuality, and excess of Rococo, seeking a return to the perceived purity, moral rectitude, and grandeur of classical antiquity. Post-Impressionism, on the other hand, reacted to Impressionism's focus on fleeting surface light and momentary observations, with artists like Van Gogh, Cézanne, and Gauguin seeking deeper emotional, structural, and symbolic content within their work. It's a constant, often exhilarating push and pull, a fascinating dialectical dialogue across time where each new generation of artists finds its voice not in a vacuum, but by either building upon, radically reinterpreting, or deliberately dismantling what came before. This isn't always a hostile act; sometimes it's a profound act of homage, where understanding the past becomes the very crucible for forging the future. For example, Post-Modernism often explicitly referenced and deconstructed previous styles, engaging in a direct conversation with art history itself, playing with irony and pastiche. This dynamic ensures that art history is never truly linear, but a rich, spiraling, and perpetually evolving conversation.

- Patronage and Art Market Dynamics: Don't underestimate the role of money and influence! The shifting landscape of patronage (from the church and royalty to the rising middle class and, eventually, a global network of collectors), the establishment of new galleries, independent salons, and influential art critics, and even entirely new ways of selling art can profoundly shape what gets created, recognized, and preserved. Think of the monumental shift from art dictated by royal commissions to independent exhibitions, which allowed movements like Impressionism to bypass the traditional academic gatekeepers entirely, forging their own path. This dynamic interplay between artists, collectors, dealers, critics, and institutions creates a complex, ever-evolving ecosystem where new movements can be nurtured, fiercely debated, promoted, and eventually, canonized into the annals of history – or, sometimes, relegated to footnotes. Consider the historical power of academic institutions and royal salons, which for centuries dictated taste and patronage. The Impressionists, for example, famously rebelled against these gatekeepers, forming their own independent exhibitions, effectively creating a new market and a new pathway for artistic recognition. The shift from church and aristocratic patronage to a burgeoning middle-class art market fundamentally changed what kind of art was created and valued. Today, the internet and globalized art markets present new challenges and opportunities for artists and movements to find their audience and sustain their vision, often bypassing traditional structures entirely, leading to a much more fragmented but potentially more democratic art world.

Core Characteristics of an Art Movement: The Ingredients of an Era

While every movement is unique, there are some common threads that tie them together, like a foundational recipe that adapts to different cultural cuisines. I find it helpful to think of these as the ingredients in a recipe for a new artistic era, each contributing to its distinct flavor and lasting impact.

Characteristic | Description |

|---|---|

| Shared Philosophy/Goals | Artists within a movement often share a common intellectual or aesthetic framework. They might be trying to achieve a specific emotional impact, explore new forms, or challenge societal norms. This philosophical backbone gives the movement its coherence and purpose, acting as its guiding star. |

| Distinct Style/Techniques | There's usually a recognizable visual language – whether it's the broken brushstrokes of Impressionism, the geometric fragmentation of Cubism, or the bold, non-naturalistic colors of Fauvism. This becomes the movement's unmistakable signature, its visual DNA. |

| Key Artists/Figures | Movements are often associated with a handful of influential artists who either pioneered the style or became its most iconic practitioners. Think of Henri Matisse for Fauvism or Piet Mondrian for De Stijl. These figures often become the public face and intellectual leaders of the movement, its central gravitational force. |

| Timeframe | While influence can be long-lasting, the active period of a movement is usually identifiable, often spanning a few decades or even less. They have a beginning, a peak, and then either fade, evolve, or splinter into new movements. Like a star, they burn brightly for a time, leaving behind a lasting light that continues to guide. | | Manifestos/Writings | Sometimes, artists within a movement will publish manifestos or theoretical writings to articulate their goals and differentiate themselves from others. This really solidifies their intellectual stance, provides a written record of their intentions, and can act as a powerful recruiting tool for new adherents. | | Exhibitions/Critics | Movements often gain traction through group exhibitions and are debated (sometimes fiercely!) by art critics and the public. This dialogue helps to define and disseminate their ideas, and often, controversy fuels their initial rise, making them impossible to ignore! | | Geographic Hubs | Many movements originate and flourish in specific cities or regions that become centers of artistic innovation, fostering a concentrated environment for shared ideas and collaboration. Think of Paris for Impressionism or New York for Abstract Expressionism. These are the crucibles where new ideas are forged. | | Public Engagement | A successful movement often manages to capture the public imagination, sparking discussion and even controversy, extending its influence beyond the art world itself and embedding itself in the broader cultural conversation. | | Medium/Technique Focus | While not exclusive, some movements are strongly defined by their innovative use of particular mediums or techniques, pushing the boundaries of what's possible with paint, sculpture, photography, or digital tools. Think of the large-scale canvases of Abstract Expressionism or the found objects of Dada. | | Cultural Resonance | An impactful movement's ideas, aesthetics, and philosophies often resonate beyond the art world, influencing fashion, graphic design, literature, and even societal values, becoming woven into the fabric of a particular era. | | Evolution and Decline| Movements rarely end abruptly. They often evolve, splinter into sub-movements, or their core ideas are absorbed into the mainstream, paving the way for the next wave of artistic innovation. Their "decline" is often just a metamorphosis. |

The Evolution of Art Movements: From Patronage to Public Sphere

Before we embark on a quick tour through specific movements, it's worth pausing to consider the grander arc of how these artistic shifts have actually evolved over time, and what that tells us about society itself. For centuries, art was largely dictated by patronage – the church, royalty, or wealthy aristocrats commissioned works, and the resulting art often reflected their values, serving specific political, religious, or decorative functions. Think of the elaborate altarpieces of the Renaissance or the opulent portraits of the Baroque era; these were not typically born of an artist's personal rebellion, but rather, a fulfillment of a patron's vision. The artist was a skilled artisan, albeit a highly revered one, working within established constraints.

The 19th century, however, saw a monumental shift, a kind of artistic emancipation. The rise of the middle class, coupled with the decline of traditional academies and the emergence of independent salons and commercial galleries, created a new space for artistic freedom and expression. Artists began to gather, not just for commissions, but to explore shared ideas, challenge established norms, and find a collective voice. This is really where the 'art movement' as we understand it today – a self-aware group of artists pushing a distinct philosophy and aesthetics – truly took root. Impressionism is a perfect example, born from artists exhibiting together outside the official French Salon system, deliberately defying academic expectations. Later, with the advent of mass media and global communication, movements could emerge and disseminate ideas even more rapidly, sometimes across continents, giving rise to phenomena like Pop Art and its engagement with consumer culture and media saturation.

Today, the landscape is even more complex and fragmented. The internet allows for instantaneous global dialogue, breaking down geographical barriers, but also a proliferation of micro-movements, individual expressions, and ephemeral digital art forms, making singular, dominant movements harder to define. Yet, the underlying human impulse to innovate, connect, and react to the world through art remains as strong as ever. Understanding this evolution helps us appreciate the intricate context in which each 'grand chapter' unfolded, and how they continue to shape the art world we inhabit.

The Global Tapestry: Art Movements Beyond the Western Canon

While this guide, like many art historical texts, tends to focus heavily on Western art movements – a reflection of their prominent documentation and influence in a particular historical trajectory – it's crucial to acknowledge that artistic innovation and collective shifts in style and philosophy are, and always have been, a global phenomenon. Every continent, every culture, has its own rich history of artistic currents, often emerging from unique social, spiritual, and political contexts. Think of the vibrant traditional arts of indigenous cultures, the complex and philosophical movements within various Asian art histories (like the literati painting traditions in China or the Edo period woodblock print movements in Japan), or the powerful and diverse art movements that arose in Africa and Latin America long before and after colonial encounters. These movements, though perhaps not always categorized with the same terminology as their European counterparts, share the same fundamental characteristics: a shared vision, distinct aesthetics, influential artists, and a profound impact on their respective societies. To truly appreciate the breadth of human creativity, we must look beyond a singular narrative and explore this magnificent, interconnected global tapestry.

A Quick Tour Through Some Iconic Art Movements

It's impossible to list every single art movement, but let's take a whirlwind tour through some of the most iconic and influential ones that really demonstrate the diversity and impact of these collective artistic journeys. You'll find many ultimate guides to individual movements on my site, so consider this a jumping-off point for your own exploration!

It's impossible to list every single art movement, but let's take a whirlwind tour through some of the most iconic and influential ones that really demonstrate the diversity and impact of these collective artistic journeys. You'll find many ultimate guides to individual movements on my site, so consider this a jumping-off point for your own exploration!

Movement | Period | Key Characteristics | Key Artists | Explore More | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Renaissance Art | 14th-17th Century | A 'rebirth' of classical ideas, emphasizing humanism, perspective, realism, and naturalism, seeking harmony and balance. Focused on the human form and rational composition. | Leonardo, Michelangelo, Raphael | Ultimate Guide to Renaissance Art | |||

| Baroque Art | Early 17th-Mid 18th Century | Dramatic, opulent, emotionally intense, and highly theatrical, often tied to the Counter-Reformation. Characterized by grandeur, movement, and rich ornamentation. | Caravaggio, Bernini, Rubens | Ultimate Guide to Baroque Art Movement | |||

| Rococo | Early-Late 18th Century | A lighter, more playful, and ornate style than Baroque, often reflecting aristocratic leisure. Characterized by delicate ornamentation, pastel colors, and themes of love, leisure, and nature. | Fragonard, Watteau, Boucher | Ultimate Guide to Jean-Honoré Fragonard: Rococo Master | |||

| Neoclassicism | Mid 18th-Early 19th Century | A revival of classical Greek and Roman art, emphasizing order, clarity, stoicism, and civic virtue, often in response to Rococo's excesses. Often starker and more rational. | Jacques-Louis David, Antonio Canova | The Definitive Guide to the History of Abstract Art Movements | |||

| Romanticism | Late 18th-Mid 19th Century | Emphasized emotion, individualism, the glorification of the past, and the awe-inspiring power of nature. Often dramatic, subjective, and imaginative, focusing on the sublime. | Delacroix, Turner, Goya | Ultimate Guide to Romanticism | |||

| Realism | Mid 19th Century | Focused on depicting subjects as they appear in everyday life, without idealization or stylization, often with a social or political commentary. A reaction against Romanticism. | Gustave Courbet, Édouard Manet | The Definitive Guide to the History of Abstract Art Movements | |||

| Impressionism | Mid-Late 19th Century | Focused on capturing fleeting moments, the effects of light and atmosphere, and outdoor scenes using broken brushstrokes and vibrant colors. Rebelled against academic painting. | Monet, Renoir, Degas | Ultimate Guide to Impressionism | |||

| Art Nouveau | Late 19th-Early 20th Century | A decorative art style characterized by organic, flowing lines, natural forms, and a sense of curvilinear elegance. Often incorporated into architecture, jewelry, and graphic design, seeking a 'total art work'. | Gustav Klimt, Alphonse Mucha, Émile Gallé | Ultimate Guide to Art Nouveau Jewelry | |||

| Expressionism | Early 20th Century | Sought to express emotional experience rather than physical reality. Characterized by distorted forms, vivid colors, and subjective perspectives to evoke mood or ideas, often born from internal angst. | Kirchner, Kandinsky, Munch | Ultimate Guide to Expressionism | |||

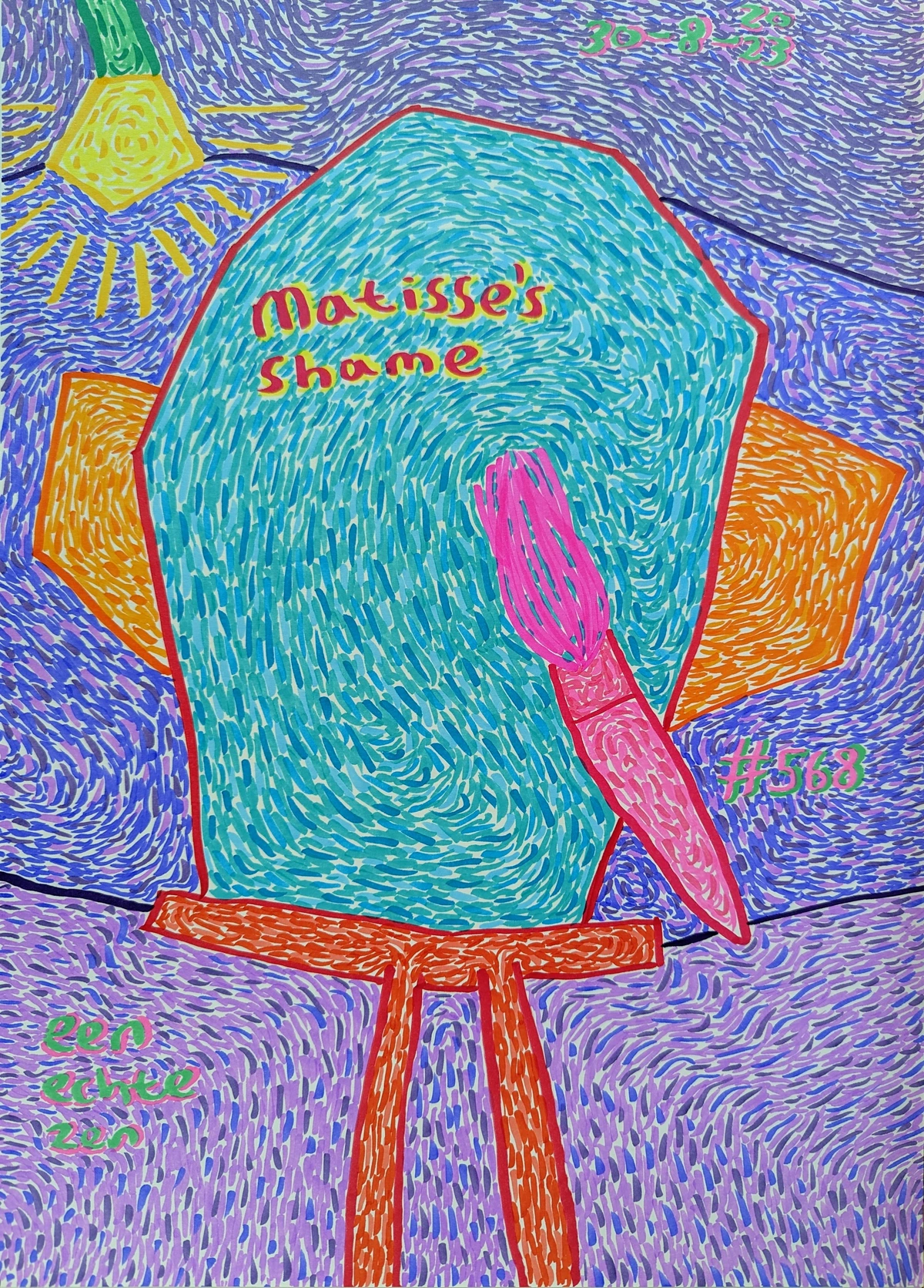

| Fauvism | Early 20th Century | Known for its intense, non-naturalistic, and often wild use of color, applied boldly and directly from the tube, prioritizing emotional expression over realism and descriptive accuracy. | Matisse, Derain, Vlaminck | Ultimate Guide to Fauvism | |||

| Dadaism | 1916-1922 | A radical anti-art movement born from the horrors of WWI, rejecting logic, reason, and traditional aesthetics. Characterized by absurdity, collage, readymades, and performance art. | Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray, Hannah Höch | The Definitive Guide to the History of Abstract Art Movements | |||

| Cubism | Early 20th Century | Revolutionized painting by depicting subjects from multiple viewpoints in fragmented, geometric forms, often abandoning traditional perspective and creating new visual realities. | Picasso, Braque, Gris | Ultimate Guide to Cubism | |||

| De Stijl | Early 20th Century | Dutch movement advocating for pure abstraction and universality through a reduction to essential forms and colors (primary colors + black/white) and horizontal/vertical lines, aiming for spiritual harmony. | Mondrian, van Doesburg | Ultimate Guide to Piet Mondrian | |||

| Suprematism | Early 20th Century | Russian avant-garde movement focused on fundamental geometric forms (squares, circles) in a limited range of colors, expressing pure artistic feeling rather than visual depiction. | Malevich | Ultimate Guide to Kazimir Malevich: Suprematism | |||

| Harlem Renaissance | 1910s-1930s | A flourishing of African American culture, particularly in literature, music, and art, centered in Harlem, New York. Focused on racial pride, identity, and socio-political commentary, celebrating Black excellence. | Aaron Douglas, Jacob Lawrence, Augusta Savage | The Harlem Renaissance: Art, Culture, and Identity | |||

| Surrealism | 1920s onwards | Explored the dream world and subconscious through illogical imagery, unexpected juxtapositions, and psychological symbolism, heavily influenced by Freudian theory, aiming to unleash the mind's full power. | Dalí, Magritte, Miró | Enduring Legacy of Surrealism | |||

| Art Deco | 1920s-1930s | A decorative style characterized by sleek geometric forms, streamlined shapes, and rich ornamentation. Often associated with luxury, glamour, technological progress, and the Jazz Age. | Tamara de Lempicka, Erte | Ultimate Guide to Art Deco Movement | |||

| Abstract Expressionism | Mid-20th Century | American movement characterized by large-scale, gestural, non-representational painting, emphasizing spontaneous action and the artist's inner emotion, often seen as a reflection of post-war angst. | Pollock, Rothko, de Kooning | The Ultimate Guide to Abstract Art Movements | |||

| Pop Art | 1950s-1960s | Challenged fine art traditions by incorporating imagery from popular culture, advertising, and consumerism, often using bright colors and bold outlines, blurring the lines between high and low art. | Warhol, Lichtenstein, Hamilton | Ultimate Guide to Pop Art | |||

| Op Art | 1960s | Short for "Optical Art," this movement creates illusions of movement, depth, and vibration through precise, non-representational patterns and geometric shapes, playing with visual perception. | Bridget Riley, Victor Vasarely | Ultimate Guide to Bridget Riley: Op Art Master | |||

| Minimalism | 1960s-1970s | Sought to reduce art to its fundamental features, emphasizing pure forms, clean lines, and often industrial materials, rejecting expressive content and illusionism, striving for objectivity. | Donald Judd, Dan Flavin, Agnes Martin | The Definitive Guide to the History of Abstract Art Movements | |||

| Conceptual Art | 1960s-1970s | Prioritized the 'idea' or concept behind the artwork over its visual form, often involving text, documentation, and ephemeral gestures, challenging traditional notions of art's purpose and commodification. | Sol LeWitt, Joseph Kosuth, Yoko Ono | The Definitive Guide to the History of Abstract Art Movements | |||

| Land Art | Late 1960s-1970s | Artists created site-specific artworks in natural landscapes, often using natural materials like earth, rocks, and water, highlighting environmental concerns and the impermanence of art, challenging the gallery system. | Robert Smithson, Andy Goldsworthy | The Definitive Guide to the History of Abstract Art Movements | |||

| Feminist Art | 1960s onwards | Challenged the patriarchal structures of the art world and society, addressing issues of gender, identity, and power through diverse mediums and often with overt political messages, seeking to empower and redefine. | Judy Chicago, Cindy Sherman, Carolee Schneemann | The Definitive Guide to the History of Abstract Art Movements | |||

| Postmodernism | Late 20th Century | A broad and diverse movement rejecting grand narratives and universal truths, embracing pluralism, irony, pastiche, and a questioning of authorship and originality across various media, often deconstructing previous styles. | Jeff Koons, Barbara Kruger, Cindy Sherman | The Definitive Guide to the History of Abstract Art Movements | |||

| Neo-Expressionism | 1970s-1980s | A return to figuration and emotional expression, characterized by raw brushwork, vivid colors, and often unsettling or dramatic subject matter, as a reaction against Minimalism and Conceptual Art, reclaiming painting's emotional power. | Jean-Michel Basquiat, Anselm Kiefer, Julian Schnabel | Ultimate Guide to Neo-Expressionism | "Optical Art," this movement creates illusions of movement, depth, and vibration through precise, non-representational patterns and geometric shapes. | Bridget Riley, Victor Vasarely | Ultimate Guide to Bridget Riley: Op Art Master |

| Minimalism | 1960s-1970s | Sought to reduce art to its fundamental features, emphasizing pure forms, clean lines, and often industrial materials, rejecting expressive content and illusionism. | Donald Judd, Dan Flavin, Agnes Martin | N/A | |||

| Conceptual Art | 1960s-1970s | Prioritized the 'idea' or concept behind the artwork over its visual form, often involving text, documentation, and ephemeral gestures, challenging traditional notions of art's purpose. | Sol LeWitt, Joseph Kosuth, Yoko Ono | N/A | |||

| Land Art | Late 1960s-1970s | Artists created site-specific artworks in natural landscapes, often using natural materials like earth, rocks, and water, highlighting environmental concerns and the impermanence of art. | Robert Smithson, Andy Goldsworthy | N/A | |||

| Feminist Art | 1960s onwards | Challenged the patriarchal structures of the art world and society, addressing issues of gender, identity, and power through diverse mediums and often with overt political messages. | Judy Chicago, Cindy Sherman, Carolee Schneemann | N/A | |||

| Postmodernism | Late 20th Century | A broad and diverse movement rejecting grand narratives and universal truths, embracing pluralism, irony, pastiche, and a questioning of authorship and originality across various media. | Jeff Koons, Barbara Kruger, Cindy Sherman | N/A | |||

| Neo-Expressionism | 1970s-1980s | A return to figuration and emotional expression, characterized by raw brushwork, vivid colors, and often unsettling or dramatic subject matter, as a reaction against Minimalism and Conceptual Art. | Jean-Michel Basquiat, Anselm Kiefer, Julian Schnabel | Ultimate Guide to Neo-Expressionism |

## The Enduring Legacy and How it Connects to My Work

Understanding art movements isn't just about historical trivia; it's about seeing the grand, sweeping evolution of human thought and creativity unfold. It gives us a crucial framework to appreciate how artists build on, react to, and sometimes completely dismantle the ideas of their predecessors. For me, it's like learning the secret language of the past to better understand the present, and to consciously (or unconsciously!) weave those historical threads into my own contemporary work.

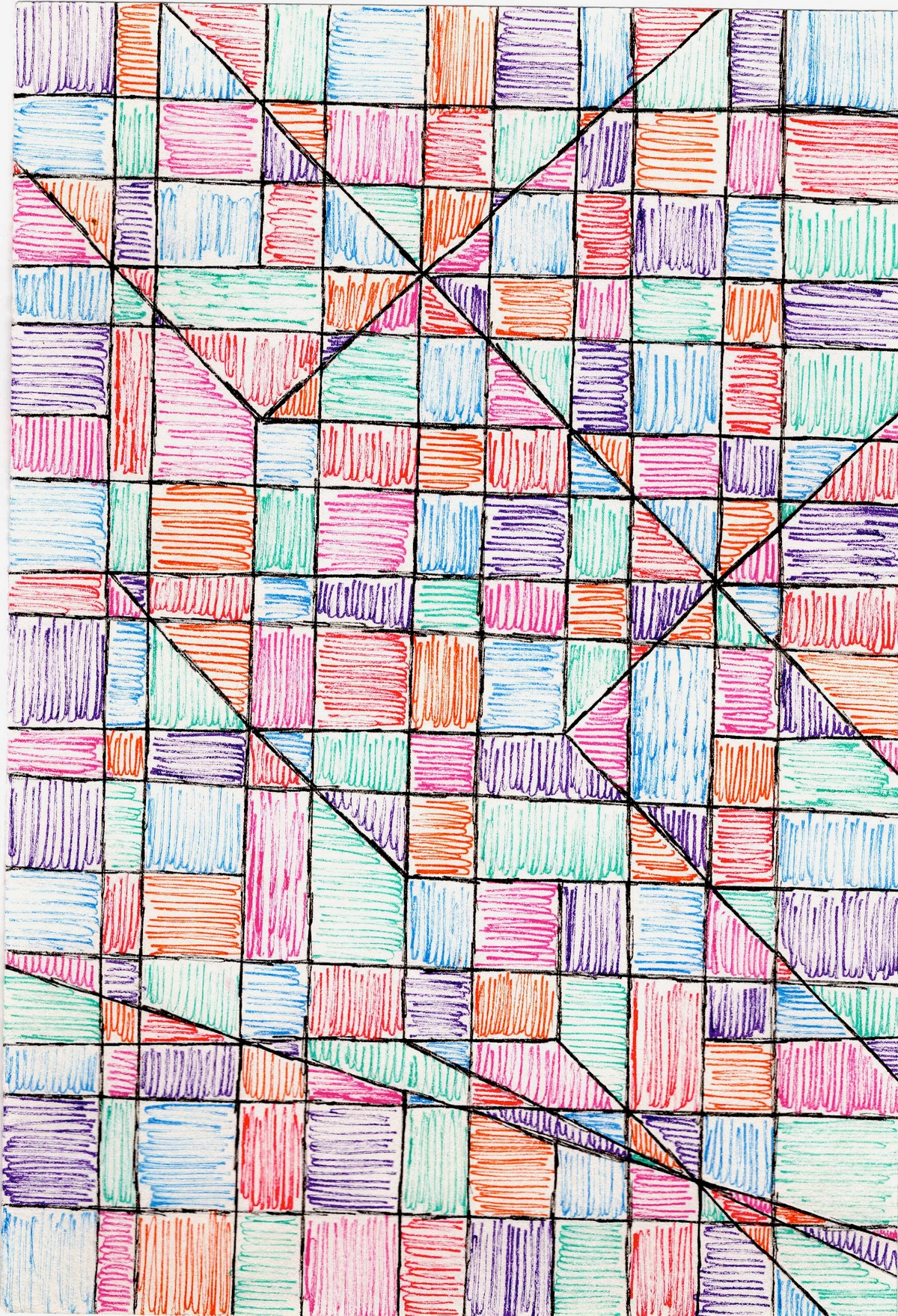

When I'm creating my own abstract art here at ZenMuseum, I'm constantly, and often unconsciously, engaging with these profound historical dialogues. It’s an ongoing conversation, a silent exchange across centuries that deeply informs my contemporary practice. The bold, uninhibited color and dynamic forms you might encounter in my pieces, for instance, certainly resonate with the raw expressive power found in movements like Fauvism or the visceral energy of Abstract Expressionism. Similarly, the underlying geometric structures that sometimes appear in my work might echo the radical principles of De Stijl or the fragmented perspectives of Cubism. Even if my conscious intention is purely contemporary – to forge something entirely new – these echoes are undeniable. It truly feels like standing on the shoulders of giants, doesn't it? Taking what resonated, twisting it with a modern sensibility, and making it profoundly my own. Every brushstroke, every color choice, every textured layer is a subtle nod to this incredible, ongoing history, a quiet yet powerful conversation across time with the masters who came before me. They provided an aesthetic language, and I'm simply finding new ways to speak it, to expand its vocabulary, and to make it relevant for today's world.

These movements provide an unbelievably rich tapestry of influences that contemporary artists, myself included, draw upon. They don't just shape; they are the aesthetic language we use, even when we're trying to forge something entirely new. It's a fantastic, lifelong journey to explore, and I wholeheartedly encourage you to dive deeper into some of these periods on my art timeline or through the various guides on my site. Who knows what inspiration you'll find for your own creative path? And remember, engaging with art history isn't just for academics; it's a vital part of nurturing your own artistic eye and spirit.

If you're ever near Den Bosch, Netherlands, you might even spot some of these influences in person at the Den Bosch Museum, where historical dialogues continue to unfold in exciting contemporary contexts.

Frequently Asked Questions About Art Movements: Your Burning Questions Answered

Q1: What's the difference between an art movement and an art style?

A: Good question, and it's a common point of confusion that I often grapple with myself! I often think of a style as the visual characteristics or techniques specific to an individual artist (like Van Gogh's swirling, impasto brushstrokes, or the ethereal glazes of a Renaissance master) or a broader, less rigidly defined aesthetic trend (think Gothic style in architecture, or the expressive brushwork you might see in my own abstract paintings). A style describes how something looks – the visual 'flair,' the signature look, the aesthetic choices. It's about the visual language itself.

An art movement, on the other hand, encompasses much more than just visual aesthetics. It's a collective phenomenon with a shared philosophy, specific goals, a defined (though sometimes fluid) timeframe, a recognizable group of artists, and almost always a direct reaction against what came before. It carries an intellectual and social underpinning, a deeper 'why' behind the 'how.' So, while Impressionism certainly has a distinct style (broken brushstrokes, capturing fleeting light, vibrant colors), it's also a movement because it was a deliberate, collective effort by a group of artists to challenge academic norms, exhibit together, publish their ideas, and articulate a radically new vision for painting. They had a shared manifesto, even if unwritten. The style, then, is a crucial component of the movement, but not its entirety; it's the visible manifestation of a deeper philosophical, social, or political shift. It's the difference between the car's paint job (style) and the entire engineering, design philosophy, and cultural impact of the car model (movement).

Q3: How long does an art movement last?

A: That's a great question, and there's no single answer! The lifespan of an art movement can vary dramatically, from a few intensely productive years to several decades, and its influence can linger for centuries. Some movements, like Dadaism or Fauvism, had relatively short active periods (roughly 5-10 years) but left an explosive impact, radically changing the course of art. Others, like the Renaissance or the Baroque, spanned well over a century. What's crucial to remember is that a movement's "end" doesn't mean its ideas vanish. Often, its core tenets are absorbed, evolve, or splinter into new, subsequent movements, demonstrating art history's continuous, flowing nature. It's less about a hard stop and more about a transformation.

Q4: Are there still new art movements emerging today?

A: Absolutely, yes! Though perhaps not always with the same centralized manifestos and clear-cut boundaries of past centuries. In our hyper-connected, globalized world, artistic shifts are often more fluid, diverse, and sometimes referred to as "micro-movements" or "trends" rather than singular, dominant movements. Digital art, net art, AI-generated art, bio-art, eco-art, and various forms of social practice art are all vibrant areas where artists are collectively exploring new technologies, addressing pressing global issues, and pushing conceptual boundaries. The instantaneous dissemination of ideas through the internet means movements can be less geographically bound and more ideologically driven. Defining them can be a challenge in real-time, but the human impulse to innovate, to connect, and to react to our world collectively through art is as strong as ever. We are living in a fascinating time of artistic fermentation!

Q2: How are art movements named?

A: It’s quite fascinating, actually, and often a little chaotic! Sometimes, the artists themselves boldly coin the term, often through a formal manifesto (like Suprematism or De Stijl), laying out their principles and giving their collective vision a distinct identity. These names are self-declarations of a new era, asserting their place in history. Other times, a critic, sometimes quite derisively, provides the name, which then, ironically, sticks – Impressionism is perhaps the most famous example, originally a jibe at Claude Monet's painting Impression, Sunrise, meant to be an insult to the "unfinished" look of the work. Similarly, Fauvism (meaning "wild beasts") was coined by a critic who was shocked by the artists' bold use of color. And then, there are names that emerge organically over time, like Renaissance, which means "rebirth," a term that historians later applied to describe that period's revival of classical ideas. So, it's a mix of self-declaration, critical commentary, and historical retrospective that gives these movements their memorable labels.

## Conclusion: The Ever-Unfolding Tapestry of Art – Your Invitation to Explore and Create

And so, we've taken a truly deep dive into what an art movement truly is – far more than just a label, wouldn't you agree? It's a fascinating, dynamic blend of collective spirit, individual genius, powerful societal forces, and, quite often, outright artistic rebellion. From the classical rebirth of the Renaissance to the fragmented realities of Cubism and the subconscious dreams of Surrealism, each movement adds another vibrant, essential thread to the rich, complex, and ever-unfolding tapestry of human creativity. They aren't just historical markers; they are the pulsating landmarks in art history, guiding us through its breathtaking evolution and reminding us of our shared human story.

## Conclusion: The Ever-Unfolding Tapestry of Art – Your Invitation to Explore and Create

And so, we've taken a truly deep dive into what an art movement truly is – far more than just a label, wouldn't you agree? It's a fascinating, dynamic blend of collective spirit, individual genius, powerful societal forces, and, quite often, outright artistic rebellion. From the classical rebirth of the Renaissance to the fragmented realities of Cubism and the subconscious dreams of Surrealism, each movement adds another vibrant, essential thread to the rich, complex, and ever-unfolding tapestry of human creativity. They aren't just historical markers; they are the pulsating landmarks in art history, guiding us through its breathtaking evolution and reminding us of our shared human story.

For me, exploring these movements isn't just about understanding the past; it's about profoundly enriching my own artistic present and sparking endless inspiration for future creations. It reminds me that art is not static or confined; it's an endless conversation, a continuous push against perceived boundaries, and a perpetual, exhilarating quest for new ways to see and express the human experience. It's truly a testament to humanity's boundless imagination. So, I urge you: keep looking, keep questioning, and keep letting art move you. The journey is truly limitless, and frankly, utterly captivating. Perhaps you'll even find inspiration for your own creative endeavors, or find a piece of contemporary abstract art that speaks to your soul right here in my online gallery. I genuinely hope you continue your own journey through art history – it’s one of the most rewarding explorations there is, and one that consistently feeds my own creative spirit. And remember, the next great movement, the next bold declaration of a new way of seeing, could very well start with you, with your unique perspective and your fearless expression. What will your unique contribution be to the ever-unfolding, magnificent story of art?