Jean-Honoré Fragonard: The Rococo Master of Playful Elegance

Explore the enchanting world of Jean-Honoré Fragonard, the quintessential Rococo master. Discover his life, vibrant techniques, and iconic works like 'The Swing,' celebrating 18th-century French art.

Ultimate Guide to Jean-Honoré Fragonard: The Rococo Master of Playful Elegance and Subtle Intrigue

If you're anything like me, you've probably stood before a Fragonard painting and felt an inexplicable pull into a world of whispered secrets and delightful abandon. Jean-Honoré Fragonard (1732–1806) isn't just an artist; he's the very soul of the late Rococo period, his entire body of work a vibrant, shimmering testament to an era defined by sensual delight, aristocratic leisure, and uninhibited joy. His canvases, alive with light, movement, and profound human emotion, transport viewers into a realm where pastoral fantasies seamlessly intertwine with intimate dalliances. I've always been fascinated by how Fragonard, at the very zenith of the Rococo, managed to capture its fleeting spirit with such unparalleled virtuosity, while also subtly hinting at the seismic shifts in art and society to come. This comprehensive guide, then, serves as your definitive resource, offering unparalleled insight into Fragonard's life, his revolutionary artistic vision, and his enduring legacy. We will explore his formative years, delve into the hallmark characteristics of his unique style, illuminate his most iconic masterpieces, and trace his often underappreciated influence, particularly his unexpected anticipation of Impressionism and his crucial role in the transition from the exuberant Rococo to the more austere Neoclassical era. For anyone seeking to understand the essence of Rococo, or simply to marvel at a master of light and human emotion, an exploration of Fragonard's body of work is not merely recommended—it is, in my view, absolutely essential. It’s an immersion into a world where beauty, pleasure, and a hint of the clandestine reigned supreme, a world he depicted with both effervescence and a surprising depth of psychological insight.

For a broader understanding of where Fragonard fits into the grand narrative of art, I often find it helpful to look at the broader sweep of history. You can explore a comprehensive timeline of art history to see how movements like Rococo emerged and evolved.

The World of Rococo: A Stage for Fragonard and the Shifting Tides of Art

The 18th century in France was a period of profound social and artistic transformation, giving rise to the Rococo movement as a stylistic evolution, and often a reaction, against the grandeur and solemnity of the preceding Baroque era. The term "Rococo" itself, derived from the French word rocaille (referring to the delicate shell-work and pebble-work used in garden grottoes and fountains), perfectly encapsulates its essence: a style that embraced a lighter, more intimate, and exquisitely decorative aesthetic. It was, in many ways, an artistic sigh of relief after the weighty pronouncements of the Baroque. Imagine the opulent, monumental scale of Versailles giving way to the charming, often whimsical, private salons and boudoirs of Parisian hôtels and country châteaux. This shift was more than just stylistic; it reflected a profound change in patronage. While Baroque art was largely commissioned by the Church and absolute monarchs for public display, Rococo found its primary patrons among the aristocracy and the burgeoning wealthy bourgeoisie. These clients sought to adorn their private spaces with art that reflected themes of love, nature, and leisurely pursuits, consciously eschewing the didacticism and weighty themes of Baroque art. Instead, they embraced a spirit of playfulness, charm, and elegant sensuality, often perceived as a deliberate counterpoint to its predecessor's severity and public monumental scale. This era fostered a rich culture of private commissions, providing fertile ground for artists like Fragonard to flourish by catering to the refined and increasingly private tastes of the French elite, creating a market perfectly suited to his intimate and emotionally resonant works. This transition from the public, monumental scale of Baroque art to the intimate, domestic focus of Rococo reflected deeper societal changes, including a move away from absolute monarchy towards a more private, pleasure-seeking aristocratic lifestyle, particularly within the lavish Parisian salons and country châteaux. This desire for more personal, ornamental, and emotionally resonant art provided fertile ground for the Rococo movement to flourish, moving away from the grand narratives of church and state to celebrate individual pleasure and sentiment. To understand this transition more fully, I often recommend exploring the ultimate guide to baroque art movement, just to get a sense of the grandeur it was reacting against.

Beyond the courtly sphere, the intellectual currents of the Enlightenment also subtly influenced Rococo's development, fostering an appreciation for natural beauty, individual sentiment, and a departure from rigid dogma. Think of Voltaire's biting wit, Rousseau's emphasis on natural rights and uncorrupted feelings, or Diderot's encyclopedic pursuit of knowledge; this growing emphasis on personal experience, individual sensibility, and the pursuit of happiness provided a fertile philosophical backdrop for the art that celebrated exactly these ideals. It was a time when human reason and individual emotions were gaining precedence, finding their artistic echo in the Rococo's intimate narratives. In a way, the Enlightenment, despite its later clash with Rococo's perceived frivolity, initially provided the intellectual oxygen for an art form focused on individual human experience. I often find it fascinating how these seemingly disparate intellectual and artistic currents converged, creating a rich tapestry of thought and expression.

For a broader understanding, I often find it helpful to delve deeper into the history of Rococo art to fully appreciate the context in which Fragonard thrived. The shift from public, grand narratives to private, intimate expressions truly defined the artistic landscape of the time, creating a fertile ground for Fragonard's particular genius. This fascination with the decorative and the intimate extended beyond painting, influencing furniture, porcelain, and even fashion, creating a holistic aesthetic that permeated aristocratic life across Europe. From the delicate porcelain figures of Sèvres to the intricately carved commodes of Boulle, the Rococo sensibility truly left its mark on every aspect of aristocratic life, forming a complete world for Fragonard's art to inhabit, a world I find endlessly captivating in its pursuit of beauty and charm.

Early Rococo was championed by seminal artists like Antoine Watteau (1684–1721), who, in my opinion, truly set the stage for Fragonard's world. Watteau's invention of the fête galante genre—depicting elegant gatherings in idealized pastoral settings—provided the thematic blueprint for much of Rococo's playful sensibility. His delicate brushwork, shimmering atmospheres, and subtle psychological insights into human relationships laid a crucial foundation, capturing a wistful, almost melancholic charm that belied the genre's surface gaiety. He showed how art could be both lighthearted and deeply expressive, hinting at deeper currents beneath the surface frivolity. Following Watteau, François Boucher (1703–1770) became the undisputed master of early Rococo, a quintessential painter of mythological idylls, allegories of love, and charming pastoral scenes. Boucher's characteristic pastel palette, fluid draftsmanship, and focus on mythological and allegorical love scenes profoundly shaped Fragonard's initial foray into the Rococo idiom. This period under Boucher established a robust stylistic foundation upon which Fragonard would build his unique vision, imbuing it with even greater dynamism, a more profound sense of human emotion, and an almost proto-Impressionistic spontaneity, pushing the boundaries of what Rococo could express. I think of Boucher as providing the vibrant stage, and Fragonard as bringing the truly unforgettable actors and their nuanced dramas to it. It's a fascinating lineage, isn't it? One master laying the groundwork for another to soar to even greater heights.

Rococo in Context: A Comparison of 18th-Century Styles

To fully grasp Fragonard's unique contribution, it is beneficial to view Rococo in contrast to the styles that immediately preceded and succeeded it:

Feature | Baroque | Rococo | Neoclassicism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Period | ~1600-1750 | ~1730-1790 | ~1750-1850 |

| Patronage | Church, Absolute Monarchs, Aristocracy (public display) | Aristocracy, Wealthy Bourgeoisie (private salons) | State, Public Institutions (moral, civic themes) |

| Themes | Grandeur, Drama, Religion, Mythology, Heroism, Power | Love, Pleasure, Fête Galante, Mythology (lighthearted), Domesticity | Reason, Virtue, Patriotism, Classical Mythology/History (didactic) |

| Style | Monumental, Dramatic, Intense Chiaroscuro, Rich Colors, Emotional Intensity, Movement | Delicate, Playful, Ornate, Pastel Colors, Asymmetry, Fluidity, Sensuality | Austere, Orderly, Clear Lines, Balanced Composition, Moral Clarity, Serenity |

| Key Artists | Caravaggio, Bernini, Rembrandt, Rubens | Fragonard, Boucher, Watteau, Chardin | David, Canova, Ingres |

| Key Themes/Motifs | Grandeur, Drama, Religion, Mythology, Heroism, Power, Public Monumentality | Love, Pleasure, Fête Galante, Mythology (lighthearted), Domesticity, Nature, Intimacy | Reason, Virtue, Patriotism, Classical Mythology/History (didactic), Morality, Order |

| Impact | Exalted religious and state authority | Celebrated aristocratic leisure and intimacy | Promoted civic virtue and republican ideals |

This table illustrates how Rococo offered a distinct artistic language, one that Fragonard would master and subtly challenge.

Who Was Jean-Honoré Fragonard?

Jean-Honoré Fragonard's journey from a modest background to the pinnacle of Rococo art is a testament not only to his innate talent but also to a certain determined dedication. Born in Grasse, a charming perfume-producing town in southeastern France, in 1732, his family faced significant financial difficulties that ultimately led them to move to Paris when Jean-Honoré was just a teenager. This move, while perhaps challenging and certainly a stark contrast to his rural upbringing, proved to be the crucible for his artistic awakening. It was in the vibrant, bustling artistic milieu of Paris that his prodigious inclinations were first recognized, setting him on a path that would intertwine with the grand masters of French painting and eventually place him at the forefront of the Rococo movement. I often wonder if the sensory richness of Grasse—its fragrant perfumes, its intense Mediterranean light, and its lush landscapes—subtly influenced his later, intensely atmospheric canvases, lending an almost palpable depth to his depiction of natural settings, a sort of pre-Impressionistic sensitivity to environment. His early life, though humble, provided the raw experiences that would later be transformed into the elegant fantasies we admire, showing that genius can blossom from unexpected soil.

Fragonard's artistic journey commenced, somewhat surprisingly, under the guidance of Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin, a master of still life and genre painting. While their styles appear worlds apart—Chardin's quiet, sober domesticity versus Fragonard's exuberant fantasy—Chardin instilled in the young Fragonard a foundational appreciation for realism, meticulous observation of everyday life, and a subtle, almost Dutch-master-like understanding of light and shadow. These seemingly disparate elements would subtly inform his later, more flamboyant style, providing an undercurrent of grounded observation beneath his fantastical flourishes, ensuring his figures felt tangible even in the most ethereal settings. This early training in careful observation, particularly of texture and the interplay of light on surfaces, would serve him incredibly well, even as his subject matter became more ethereal and emotionally charged, a testament to the enduring lessons of fundamental artistry. I think it's a beautiful example of how even contrasting influences can contribute to a unique artistic voice, much like a chef learning from different culinary traditions.

However, it was under François Boucher (1703–1770), the undisputed master of early Rococo, that Fragonard's delicate touch and vibrant palette truly blossomed. Boucher, a court painter who excelled at mythological and allegorical love scenes, provided Fragonard with a stylistic roadmap, teaching him the art of gracefully rendered figures, lush drapery, and a captivating lightness. His training, focusing on charming and often erotic narratives, along with his characteristic pastel palette and fluid draftsmanship, profoundly shaped Fragonard's initial foray into the Rococo idiom. This period under Boucher established a robust stylistic foundation upon which Fragonard would build his unique vision, imbuing it with even greater dynamism, expressive brushwork, and a heightened, almost tangible, sensuality, ultimately surpassing his master in emotional range and sheer vivacity. I find it fascinating how he absorbed these influences and then, almost effortlessly, made them entirely his own, transcending mere imitation to forge a truly unique artistic voice, a characteristic I see in many great artists who stand on the shoulders of giants. It's almost as if he took Boucher's stage and then brought it to life with an entirely new, electrifying performance.

His prodigious talent was quickly recognized, culminating in the prestigious Prix de Rome in 1752. This scholarship funded study in Italy at the French Academy, a truly pivotal period that allowed him to immerse himself deeply in classical masterpieces. He devoured the monumental works of the High Renaissance and Baroque masters such as Michelangelo, Raphael, and Rubens, and intensely studied the evocative Italian landscape. I imagine him poring over their techniques, absorbing lessons in grand compositions, dramatic narratives, and the powerful interplay of light and shadow, even as he refined his distinctively Rococo sensibility. He was particularly drawn to the vibrant color and dynamic compositions of Venetian masters like Giovanni Battista Tiepolo and Paolo Veronese, whose luminous palettes and effortless movement left a lasting impression, clearly influencing his later exuberance and his unique ability to depict shimmering atmospheric effects. He wasn't just copying; he was internalizing the grandeur and drama, and then filtering it through his own, uniquely playful and sensual lens, a true mark of genius.

While in Italy, Fragonard also sketched extensively, often en plein air, capturing the fleeting beauty of the Roman campagna, the architectural splendors of Rome, and the serene gardens of the Villa d'Este. This practice of direct observation and rapid execution, using lively chalk and wash, honed his ability to render atmospheric effects with remarkable spontaneity. It was this almost insatiable desire to capture the immediate visual sensation that would define his later career, significantly anticipating the spontaneous approach of Impressionism decades before its formal emergence. He wasn't just copying; he was internalizing the grandeur and drama, and then filtering it through his own, uniquely playful and sensual lens. This meticulous yet freehand approach was truly groundbreaking for its time, laying the groundwork for much that would follow in modern art.

This dedication to capturing light and atmosphere directly from nature, even while studying the Old Masters, set him apart. His notebooks from this period are filled with vibrant sketches that pulse with life, demonstrating a fresh, immediate approach that was truly revolutionary for its time. These studies, often executed in red chalk or bistre wash, showcase an early mastery of capturing fleeting moments and effects, prefiguring the spontaneity that would define his most celebrated canvases. It was this rigorous yet liberated approach to observation that fueled his later genius, truly a foreshadowing of the Impressionist movement.

Upon his return to Paris in 1761, Fragonard initially harbored ambitions of establishing himself as a historical painter, then considered the most esteemed genre, often commissioned by the Royal Academy. He even presented his impressive work Coésus and Callirhoé (1765) to the Academy, receiving a commission for a larger version. This early work clearly demonstrated his academic prowess and capacity for grand narrative, proving he could master the lofty themes expected of a serious artist. However, despite this initial success, the grandeur, moral gravity, and didacticism inherent in historical painting ultimately proved less suited to his inherent temperament and burgeoning talent for capturing fleeting moments of human intimacy. It was his innate ability to infuse scenes with charm, sensuality, and psychological nuance—depicting the stolen kiss, the secret rendezvous, the idyllic picnic, and charming domestic vignettes—that truly captivated his aristocratic clientele. His spontaneous, fluid, and vibrant style was perfectly suited to the private decorative schemes of the period, allowing him to largely bypass the more rigid academic system and flourish instead in the burgeoning private art market. He swiftly became the darling of French society, his canvases adorning the most fashionable salons and private boudoirs, perfectly suiting the era's demand for art that celebrated pleasure, intimacy, and a certain refined frivolity, much to the chagrin of more conservative critics who yearned for art of moral instruction rather than sheer delight. I often think of this period as his moment of self-discovery, where he realized his true artistic calling lay not in grand pronouncements, but in the intimate whispers of the human heart.

Signature Style & Techniques

Jean-Honoré Fragonard's distinctive style is characterized by several key elements, each contributing to the enduring appeal and revolutionary nature of his work. I think what truly sets him apart is his seemingly effortless command of these elements, blending traditional skills with an audacious spontaneity. His innovative approach to paint handling, color, and composition not only defined the late Rococo but also subtly anticipated many innovations of later art movements such as Impressionism and even aspects of modern abstraction. He wasn't just a Rococo painter; he was a bridge to a new way of seeing, pushing the boundaries of what was considered acceptable and exploring new visual languages.

The Art of the Brushstroke: Fluidity and Expression

Fragonard's virtuosity with the brush is perhaps his most recognizable trait, demonstrating a radical freedom for his era. His brushstrokes are famously loose, dynamic, and seemingly effortless, often executed alla prima (wet-on-wet) to capture the immediacy of a moment with remarkable speed and freshness. This direct, spontaneous painterly approach imbued his figures and landscapes with an unparalleled sense of movement and vivacity, allowing for soft, almost blurred transitions and richly textured surfaces that invite the viewer's eye to dance across the canvas. This bold technique not only conveyed a sense of fleeting light and ephemeral movement but also contributed to the overall lightness and informality characteristic of Rococo art. Furthermore, Fragonard often utilized judicious amounts of impasto—thickly applied paint—in areas he wished to highlight, creating textured surfaces that catch the light and add to the illusion of movement and depth. He employed a sophisticated variety of brushes, from broad flat ones for sweeping movements and lush foliage to fine pointed tips for delicate facial features and intricate costume details, showcasing a masterful control that belied the apparent spontaneity. It's this seemingly effortless yet incredibly skilled handling of paint that I believe directly paved the way for later movements, especially for the Impressionists, who would take such visible brushwork to new extremes. It's almost as if he was painting with light itself, a true alchemist of the canvas.

The Luminous Palette: Colors of Delight and Dream

While embracing the delicate pastel hues characteristic of Rococo—pinks, sky blues, creams, and greens—Fragonard often elevated his compositions with brilliant accents of rose, gold, vibrant emeralds, and deep sapphires, creating a dynamic interplay of subtle and bold tones. His masterful use of glazes (thin, transparent layers of paint applied over a dry underlayer to enrich color and luminosity) and scumbles (thin, opaque layers of paint applied lightly over a dry base) created a shimmering, almost iridescent quality, making his scenes appear bathed in a soft, ethereal light, almost as if the canvas itself was glowing from within. This luminous effect was crucial in rendering the atmospheric depth and dreamlike quality of his pastoral and intimate scenes, enhancing their delicate gaiety and infusing them with a palpable sense of warmth and vitality. The subtle gradations of light and shadow achieved through these techniques contribute significantly to the overall charm and emotional resonance of his work. It’s worth noting that Fragonard was also known for his experimental use of pigments, often mixing his own, which allowed him a unique vibrancy and luminosity not always seen in his contemporaries. His understanding of how these pigments would interact with light, and with each other, was truly exceptional, contributing to the distinctive glow of his canvases. This mastery of color and light is, to me, one of his most profound legacies, truly setting him apart from his peers, a testament to his painterly alchemy. It’s a bit like a magician conjuring light from thin air, don't you think?

Themes: Love, Leisure, and the Fête Galante

Fragonard's art is an unabashed celebration of sensuality, flirtation, and the idyllic aspects of love, almost invariably set within dreamlike pastoral landscapes or elegant interiors. He perfected the fête galante, a genre depicting aristocratic revelries and graceful gatherings in enchanting outdoor settings, transforming seemingly everyday encounters into scenes of elegant fantasy and playful escapism. These works often feature finely dressed figures engaged in music, lively conversation, or discreet amorous pursuits amidst lush gardens and classical ruins, vividly capturing the sophisticated frivolity and refined pleasures of the era. Beyond the overt charm and surface gaiety, Fragonard’s intimate domestic scenes often subtly hint at deeper psychological nuances, exploring the complexities of human relationships and unspoken desires with a keen and empathetic eye, suggesting narratives beyond the immediate visual delight. In some instances, his works carry a subtle allegorical weight, referencing classical myths or literary themes without being overtly didactic. These allusions add layers of meaning for the educated viewer, inviting a deeper engagement with the art that transcends mere visual pleasure, inviting a deeper intellectual as well as aesthetic appreciation. He truly mastered the art of suggestion, a skill I believe is essential for any enduring work of art, allowing the viewer to participate in the narrative rather than just observe it. It's like he's inviting us to complete the story in our own minds.

Dynamic Compositions and Narrative Flow

Fragonard masterfully employed diagonal lines, swirling drapery, and asymmetrical arrangements to guide the viewer’s eye through intricate narratives. This radical departure from Baroque monumentality—which typically favored strict balance and classical restraint—added to the overall sense of dynamism, spontaneity, and delightful disorder, making his scenes feel remarkably alive and immediate. He often utilized dramatic angles and implied movement, coupled with a subtle sense of theatricality, to create an impression of unfolding action, drawing the viewer into the story as if witnessing a private moment or a stage play in progress. A technique I particularly admire is his frequent use of repoussoir—where a figure or object in the foreground, often silhouetted, directs the viewer's eye into the depth of the composition, amplifying the sense of spatial illusion and drawing you into the scene, effectively creating a sense of voyeurism and intimate participation. This wasn't just a compositional trick; it was a psychological device, pulling the viewer into the narrative, making them feel like a clandestine observer, much like we see in The Swing. It's a subtle way of making you complicit in the scene, which I find utterly compelling.

Mastery of Foreshortening and Spatial Illusion

Beyond merely dynamic compositions, Fragonard also demonstrated a keen understanding of foreshortening and spatial illusion. He frequently employed these techniques to enhance the sense of depth and three-dimensionality in his figures and settings, making them project convincingly into the viewer's space. This added layer of realism and engagement further amplified the immersive quality of his scenes, ensuring that even the most fantastical fête galante felt tangible and immediate. His figures are never flat; they possess a captivating volume that lends itself to their lively interactions. This volumetric quality, combined with his dynamic poses, gives his scenes a tangible, almost theatrical presence, truly making you feel as if you could step into the canvas. It's a testament to his mastery that he could create such illusions of reality even within his most fantastical settings.

Mastery of Light and Shadow: Chiaroscuro and Luminescence

Beyond his vibrant palette, Fragonard was adept at using strong contrasts between light and dark (chiaroscuro), especially in his later works like The Bolt. This technique amplified the emotional intensity and dramatic tension in his compositions, allowing him to explore more morally ambiguous or dramatically charged subjects. Simultaneously, his unique ability to depict soft, dappled light filtering through foliage and shimmering atmospheres (luminescence) contributed to the ethereal and dreamlike quality prevalent in his fête galante scenes, showcasing a versatility that transcended purely lighthearted themes. His understanding of how light interacts with form and texture creates a tangible sense of atmosphere in all his works, making his scenes breathe with a captivating naturalism, whether bathed in sunlight or shrouded in dramatic shadow. This nuanced approach to light, moving beyond simple illumination to convey emotion and atmosphere, is a hallmark of his genius and a significant departure from the more stark, sculptural light of Baroque art. It's almost as if he painted the very air itself, infusing his canvases with a palpable sense of presence.

Drawing and Printmaking Mastery

While celebrated primarily for his oil paintings, Fragonard was also a prolific and virtuoso draftsman, producing an astonishing number of works on paper. He frequently utilized a range of media, including red chalk, black chalk, sepia wash (often bistre), and sometimes white gouache highlights, to create both meticulous preparatory studies and strikingly spontaneous finished drawings. These drawings are renowned for their vitality, fluid lines, and remarkable immediacy. Often executed with incredible speed, they demonstrate his keen observational skills and his uncanny ability to capture movement, gesture, and emotion with minimal yet expressive lines. These graphic works reveal a raw energy and directness, showcasing his mastery of line, tone, and atmospheric effect, and providing invaluable insight into his creative process. Highly sought after by collectors in their own right, these drawings further cemented his reputation as a versatile master. Fragonard also experimented with etching, translating some of his compositions into prints, a practice that helped disseminate his distinctive style to a wider audience across Europe. His prints, like his drawings, possess a remarkable immediacy and fluidity, showcasing his mastery of line in a different medium. These works often served as studies or as means to circulate popular designs, further extending his artistic reach, allowing his unique vision to permeate beyond the canvases of private collections. It's fascinating how his drawing practice was not merely preparatory but a significant artistic output in itself, demonstrating his complete mastery across different mediums, a true testament to his relentless creativity.

![]() credit, licence

credit, licence

Masterpieces & Iconic Works

Fragonard’s legacy is enshrined in a collection of works that define the Rococo aesthetic, showcasing his extraordinary range from lighthearted flirtation to dramatic intensity. These works continue to captivate audiences with their beauty, dynamism, and profound emotional resonance. Here are some of his most celebrated pieces, each a testament to his unique ability to capture the fleeting moments of 18th-century life with unparalleled skill:

The Swing (La Balançoire)

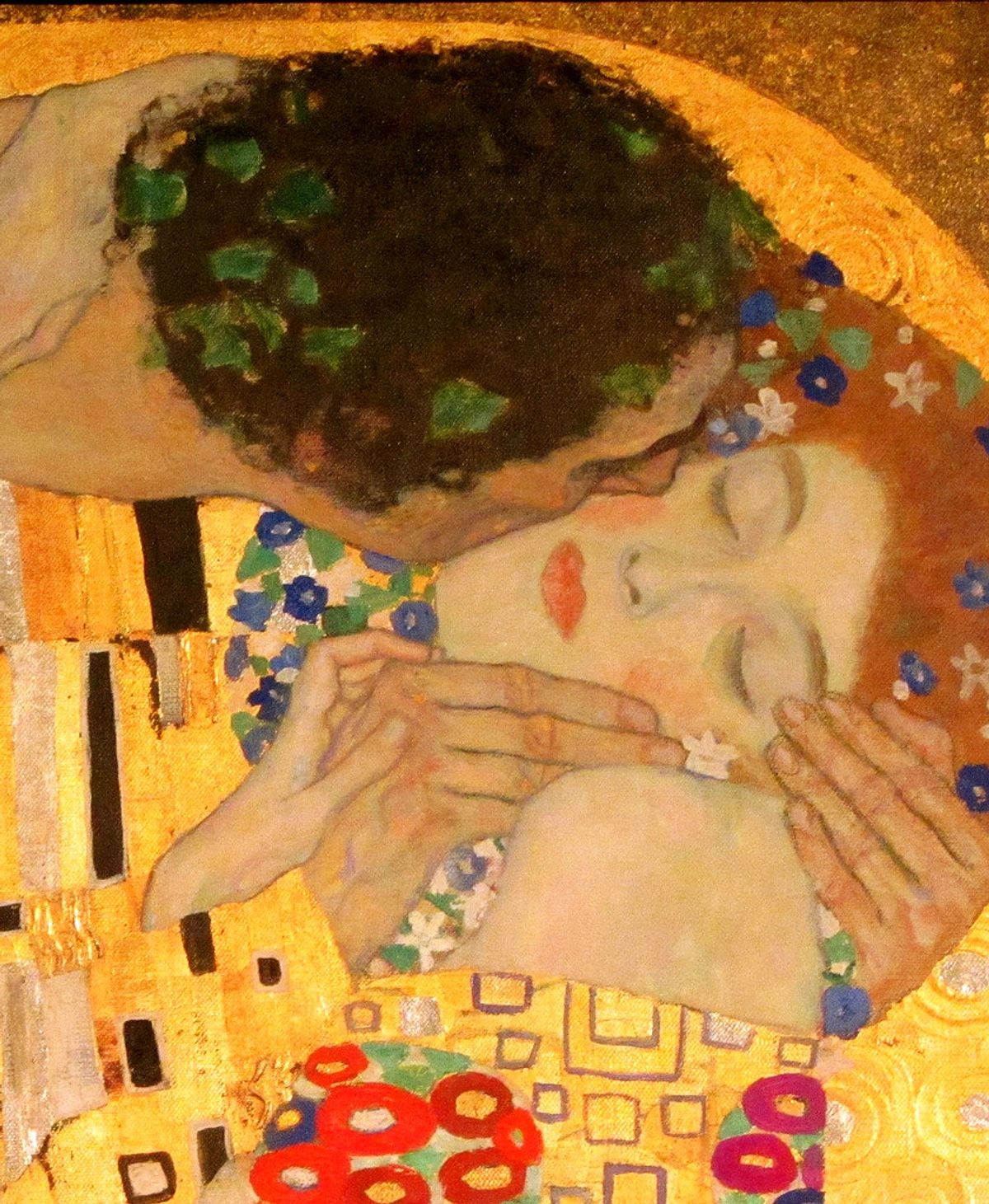

Perhaps Fragonard's most famous work, The Swing (c. 1767) stands as the absolute epitome of Rococo playfulness and hidden sensuality. Commissioned by a wealthy baron, Baron de Saint-Julien, who reportedly wished to see his young mistress on a swing, being pushed by a complaisant old man (often interpreted as a bishop or a cuckolded husband), while he himself could glimpse her ankles from below, the painting is a delightful tableau of aristocratic folly and covert desire. Set within a lush, overgrown jardin à la française—a fantastical, almost theatrical, outdoor stage—the delicate pastel colors, luxuriant foliage, and the swirling drapery of the young woman all contribute to its iconic status. The composition, with its dynamic triangular arrangement and implied movement, makes it a quintessential representation of 18th-century French aristocratic life and its playful eroticism. Beyond its scandalous narrative, the technical brilliance of the work—with its exquisite rendering of dappled light filtering through the leaves, rich textures, and vibrant dynamism—cements its place as a masterpiece that perfectly encapsulates the charm, moral ambiguity, and artifice of the era. I often find myself pondering the subtle symbolism here: the kicked-off slipper, hinting at lost innocence or carefree abandon; the strategically placed Cupid statues, witness to the illicit flirtation; and the overgrown garden itself, a metaphor for uncontrolled passion—each element seems to whisper of fleeting pleasures and hidden desires, making it a feast for both the eyes and the mind. It’s a painting that invites endless interpretation, a true testament to its complexity beneath the surface charm. It truly makes you wonder about the conversations that must have taken place in those opulent Parisian salons.

A Young Girl Reading (La Liseuse)

One of Fragonard's most beloved and intimate works, A Young Girl Reading (c. 1776) captures a profound moment of quiet contemplation, representing a delightful and significant departure from his more exuberant fête galante scenes. The painting depicts a young woman, possibly a middle-class sitter, dressed in a vibrant saffron-yellow dress with a white ruff, engrossed in a book, her identity and the book's content deliberately left ambiguous. Her head is tilted, her attention fully absorbed by the text, framed by the soft, expressive brushwork that is Fragonard's hallmark. The light gently illuminates her face and the pages, emphasizing the intimacy and psychological depth of the scene. This work is celebrated for its delicate color palette, fluid execution, and tender, almost proto-Romantic portrayal of a private, intellectual, and contemplative moment. It offers a poignant glimpse into the domestic life and evolving sentiments of the Rococo era, highlighting Fragonard's remarkable versatility beyond purely aristocratic fantasies and his ability to evoke profound human emotion in moments of quiet solitude. This work, I believe, showcases his capacity for a subtle psychological realism, capturing a universal moment of absorption that transcends the aristocratic setting and speaks to the quiet joys of intellectual pursuit. It's a beautiful counterpoint to his more boisterous compositions, revealing the breadth of his emotional range and, dare I say, hinting at the introspection that would define later Romanticism. It makes me think about the enduring power of a quiet moment of connection with a good book, even centuries later.

The Bathers

This iconic work (c. 1765-1767) showcases Fragonard's unparalleled ability to depict natural beauty and the human form with exquisite grace and vitality. The soft, dappled light filtering through lush foliage, the playful interaction of the nude figures, and the extraordinarily fluid brushwork converge to create a scene of pure, unadulterated sensuality, set within an idealized natural landscape. It embodies the Rococo ideal of harmonious interaction between figures and nature, subtly referencing classical mythological themes of nymphs, goddesses, and putti without being explicitly didactic or overtly narrative. The vibrant brushwork and luminous colors capture the fleeting movements of the bathers, emphasizing the joy, freedom, and almost primal innocence of the natural world, a hallmark of Fragonard's playful classicism. The composition, often described as a "pyramid of flesh," adds to its dynamic and timeless appeal, demonstrating his mastery of complex multi-figure arrangements, a compositional genius that few could rival.

The Progress of Love Series

Commissioned by Madame du Barry, King Louis XV’s last mistress, for her newly built Château de Louveciennes, this ambitious series (1771-1773) originally comprised four monumental paintings: The Pursuit, The Rendezvous, The Declaration of Love, and The Lover Crowned. These works beautifully illustrate the unfolding stages of courtship and love, set against lush, classical gardens characteristic of Fragonard's idyllic visions, replete with statues, fountains, and vibrant flora. Each panel captures a distinct moment in a romantic narrative, from initial pursuit to the culmination of affection, rendered with Fragonard's characteristic dynamism and shimmering light. However, in a significant and rather dramatic turn of events, Madame du Barry ultimately rejected the series. Her stated reason was that their lighthearted Rococo style clashed with her evolving, more Neoclassical tastes, which were then gaining prominence, or perhaps the rejection was fueled by political maneuvering against Fragonard himself, a common occurrence in the Machiavellian court of Versailles. Consequently, Fragonard later painted two additional, more reflective panels for his cousin's house in Grasse: Reverie and Friendship, which were often considered to be a commentary on the fleeting nature of love and patronage, perhaps even a subtle artistic rebuttal. The rejected series eventually found its permanent home in the Frick Collection in New York, where it remains one of the most celebrated ensembles of Rococo art. This rejection, while initially a blow to Fragonard, also serves as a poignant historical marker. It wasn't merely a clash of personal taste, but a reflection of the rapidly shifting artistic and political currents in pre-Revolutionary France. The grand, neoclassical ideals championed by figures like Jacques-Louis David were beginning to gain traction, rendering the Rococo's playful sensuality increasingly unfashionable in elite circles, making this series a fascinating document of a turning point in art history, a swan song for an era. It’s a compelling reminder of how art is inextricably linked to the social and political fabric of its time, and how tastes can change with startling rapidity.

The Bolt (Le Verrou)

In stark contrast to the overt lightness and aristocratic frivolity of The Swing, The Bolt (c. 1777-1778) offers a far more dramatic and intense depiction of a clandestine, possibly illicit, encounter. The masterful use of chiaroscuro (strong contrasts between light and dark) amplifies the tension and raw passion of the moment, focusing on the dramatic action of a man bolting a door, sealing off a private, intensely charged scene. This work showcases Fragonard's profound versatility beyond purely lighthearted themes, venturing into a more morally ambiguous and psychologically complex narrative. It stands as a powerful exploration of human desire, the theatricality of intimate moments, and the fragility of societal norms, executed with a raw energy that was remarkably ahead of its time. The Bolt thus pushes the boundaries of Rococo subject matter, foreshadowing a proto-Romantic sensibility in its emotional intensity. The symbolism of the bolt, the rumpled bed, and the dramatic, almost stark, lighting all contribute to a heightened sense of tension, forbidden passion, and the narrative's underlying urgency. Interestingly, The Bolt is often considered a companion piece to another Fragonard painting, The Contract (also known as Le Contrat), which depicts a more formal, perhaps arranged, marital agreement. This pairing highlights Fragonard's exploration of love's varied forms, from societal conventions to raw, impulsive desire, offering a nuanced commentary on the complexities of human relationships. This duality is a profound statement on the human condition itself, don't you think? It reveals a Fragonard capable of much more than just pretty surfaces, delving into the darker, more complex corners of human experience.

The Music Lesson

Another exquisite example of Fragonard's intimate genre scenes, The Music Lesson (c. 1769) portrays a young woman receiving instruction on a stringed instrument, likely a theorbo or lute, from a male tutor. The scene is imbued with a characteristic Rococo charm and subtle flirtation, a gentle interplay of gazes, gestures, and proximity that hints at a budding romance or shared intimacy beneath the veneer of formal instruction. The soft, luminous light, the elegant drapery, and the delicate expressions of the figures exemplify Fragonard's mastery in capturing intimate moments of aristocratic life with grace and psychological nuance. This work demonstrates his ability to imbue seemingly everyday interactions with a sense of playful intrigue and emotional depth, reflecting the sophisticated social rituals of 18th-century French society. Unlike the quiet domesticity one might find in a Chardin genre scene, Fragonard infuses this setting with an undeniable flirtation, turning a simple lesson into a stage for human connection and burgeoning romance. It's a subtle but powerful difference, showcasing his unique approach to the genre, transforming a routine activity into a tableau of budding desire, a glimpse into the intimate social dances of the era, truly making it his own.

Blind Man's Bluff (Colin-Maillard)

Fragonard’s painting Blind Man's Bluff (c. 1750-1752, or a later version around 1775) beautifully encapsulates the playful spirit of the Rococo and is a prime example of the fête champêtre genre. Depicting a group of elegantly dressed young men and women engaged in the popular parlor game amidst a sun-dappled, luxuriant park, the work is a testament to Fragonard's ability to infuse everyday leisure with an air of sophisticated charm and subtle flirtation. The swirling forms, vibrant colors, and dynamic poses perfectly capture the fleeting joy and innocence of youth, while subtly hinting at the underlying romantic tension and societal rituals of courtship common in the 18th century. The fête champêtre, a lighter, more pastoral variation of the fête galante, focused on idyllic rural settings and informal aristocratic amusements, which Fragonard mastered with unparalleled skill, making this work a vibrant testament to his ability to convey both exuberant energy and nuanced emotion. These scenes were not just visually appealing; they offered a glimpse into the idealized world of aristocratic leisure, a world Fragonard captured with both charm and a subtle critique, subtly revealing the complex social dynamics beneath the surface playfulness, a fascinating blend of celebration and observation. It’s a delightful window into a world where even games are infused with romance.

Fragonard’s Patrons and the 18th-Century Art Market

Fragonard's success was inextricably linked to the burgeoning art market and the specific tastes of the French aristocracy in the 18th century. Unlike the previous era dominated by church and state commissions—where Baroque artists served powerful institutions—Rococo artists found their primary patrons among wealthy private collectors. These clients sought art for their intimate Parisian hôtels and country châteaux, preferring themes that celebrated personal pleasure, domesticity, and the idyllic life rather than grand historical or religious narratives. This shift in patronage fostered a more personal and intimate relationship between artist and client, allowing for greater artistic freedom in certain genres and encouraging artists to specialize in subjects that catered to private sensibilities, a dynamic that Fragonard exploited to perfection, almost becoming a confidante to his patrons' desires.

His primary patrons included influential financiers and members of the burgeoning upper bourgeoisie, such as Pierre Jacques Onésyme Bergeret de Grancourt, who provided Fragonard with significant financial support and commissions during his early career, notably accompanying him on his second trip to Italy. Other prominent patrons included the actress Madeleine Guimard, for whom he decorated a private theatre, and the ambitious collector Louis-François de Bourbon, Prince de Conti. These individuals not only purchased his works but often housed him, allowing him dedicated time for creation, a common practice of the era. The rise of the Salon exhibitions also played a crucial role, offering artists a public platform to display their work and attract new clientele, though Fragonard sometimes preferred to work directly for private patrons, circumventing the more formal academic system. This preference allowed him to maintain his distinct, spontaneous style, often working outside the dictates of academic conventions and subject matter. It's also important to remember the growing influence of art critics and writers during this period, such as Denis Diderot. Their reviews and commentaries in the Salons played a significant role in shaping public taste and opinion, sometimes championing, sometimes critiquing, the very style that Fragonard embodied, making the art market of the 18th century a complex and vibrant ecosystem. It was a fascinating interplay of aristocratic demand, artistic freedom, and evolving critical discourse. I often find this dynamic of private patronage versus public display to be a recurring theme throughout art history.

Fragonard’s Influence & Legacy

Fragonard's artistic career spanned a period of significant change. While he was highly successful during the height of the Rococo, the shift in taste towards the more austere and morally serious Neoclassical style, championed by artists like Jacques-Louis David, saw his popularity wane significantly. The French Revolution further cemented this change, as his art was deemed too frivolous and aristocratic for the new political climate, which prioritized civic virtue and historical grandeur.

However, in the 19th century, particularly with the rise of the Impressionists, Fragonard’s loose, visible brushwork, vibrant colors, and profound focus on capturing fleeting light and atmospheric effects found new and enthusiastic admiration. Artists like Pierre-Auguste Renoir (who, like Fragonard, painted scenes of leisure and social life with a fluid touch) and Edgar Degas (with his dynamic compositions and emphasis on movement) looked back to Fragonard's spontaneity and dynamic compositions, recognizing a kindred spirit in his rejection of academic rigidity and his embrace of immediate visual sensation. His ability to render shimmering light, depict dappled foliage, and capture movement with broad, visible strokes directly anticipated the core concerns of Impressionism, making him a fascinating and crucial precursor to the movement. Think of the Impressionists' fascination with light's fleeting effects, their loose brushwork, and their focus on contemporary life—all elements Fragonard was exploring well over a century earlier, albeit through a Rococo lens. This direct lineage, though often overlooked, highlights his groundbreaking approach to paint application and observation. For more on this influential art movement, one can explore the ultimate guide to impressionism, and see how Fragonard's vision truly laid some foundational groundwork. His influence can even be subtly traced in the decorative arts and interior design of later periods, notably in the Belle Époque, where a renewed appreciation for elegance and ornamentation echoed Rococo's spirit. It's a testament to his timeless appeal that his work continues to resonate across centuries.

He is now celebrated not only as the last great master of the Rococo but also as a crucial bridge to modern painting, anticipating many of the stylistic innovations that would emerge decades later, including the emphasis on subjective experience, expressive technique, and a proto-Romantic sensibility evident in works like The Bolt. His influence can even be subtly traced in the decorative arts and interior design of later periods, notably in the Belle Époque, where a renewed appreciation for elegance and ornamentation echoed Rococo's spirit. It's a testament to his timeless appeal that his work continues to resonate across centuries. It's a bit like discovering an ancestor who was far more ahead of their time than anyone realized.

The Fête at Saint-Cloud

Among Fragonard's large-scale fête champêtre paintings, The Fête at Saint-Cloud (c. 1775-1780) stands as a vibrant testament to aristocratic leisure and public festivity. The painting depicts a bustling open-air festival in the meticulously manicured gardens of the Château de Saint-Cloud, filled with elegantly dressed figures enjoying games, music, conversation, and various social interactions. It masterfully captures the effervescent spirit of both public and private festivities of the era, showcasing Fragonard's extraordinary ability to manage complex compositions with numerous figures and intricate groupings while maintaining an overriding sense of lighthearted charm and dynamism. The painting's expansive landscape and lively crowd scenes highlight his mastery of depicting atmospheric effects, the interplay of light and shadow, and the joyous energy of collective merriment, making it a compelling snapshot of 18th-century French social life. Look closely, and you'll find charming vignettes: couples flirting, children playing, vendors selling their wares—each figure contributing to the bustling tapestry of a truly vibrant scene, revealing Fragonard's keen eye for social observation. It’s a masterpiece of organized chaos, where every detail adds to the overall joyous energy, making it a truly immersive experience.

The Love Letter

The Love Letter (c. 1770) is another exquisite example of Fragonard's intimate genre scenes, depicting a young woman caught in the act of writing or perhaps secretly receiving a love letter. The painting is characterized by its delicate palette, fluid brushwork, and the tender, almost conspiratorial atmosphere that draws the viewer into the private world of the sitter. Her absorbed expression, framed by the soft, diffused light, emphasizes the privacy and emotional intensity of the moment, suggesting a world of hidden sentiments and romantic longing. This work perfectly embodies the Rococo fascination with romantic intrigue, sentimental narratives, and the nuanced emotional landscapes of 18th-century individuals, offering a captivating and empathetic glimpse into their personal lives. The tender light and the subject's absorbed expression create a compelling intimacy, inviting the viewer to speculate on the secrets held within the letter, showcasing Fragonard's talent for narrative suggestion. This ability to imply a rich inner world with a single, perfectly captured moment is a hallmark of his genre scenes. It's a subtle form of storytelling that engages the viewer's imagination, a quality I find particularly compelling in his work, a true masterpiece of emotional subtlety.

Fragonard and the French Revolution: A Turning Point

The tumultuous events of the French Revolution (1789-1799) profoundly impacted Fragonard's life and career. As the aristocracy, his primary patrons, faced persecution, imprisonment, or emigration, the demand for his lighthearted, pleasure-filled Rococo canvases evaporated almost overnight. The new political climate favored the austere morality and civic virtue embodied by Neoclassical art, championed by artists like Jacques-Louis David. This dramatic shift rendered Fragonard's style, once so celebrated, seemingly irrelevant to the new political and social order.

Life During and After the Revolution

Fragonard, once the darling of Parisian society, found himself abruptly out of favor and largely unemployed, a stark contrast to his earlier successes. The aristocratic patronage base that had sustained him for decades had either fled, been imprisoned, or executed during the tumultuous events of the Revolution. He eventually returned to his native Grasse with his family, including his wife Marie-Anne Gérard and their children, seeking refuge from the Parisian chaos. However, Fragonard’s story during this period isn't solely one of decline. Demonstrating remarkable adaptability, he took on a crucial role as a conservator and administrator at the newly formed Central Museum of Arts (which would later become the Louvre Museum), working tirelessly to protect, inventory, and organize the vast nationalized art collections. This important position, secured through the influence of his friend and former student Jacques-Louis David—despite their stark artistic differences—offered him a degree of stability amidst the societal upheaval. While his personal artistic output diminished significantly as public taste shifted dramatically, his administrative contributions during this critical period were invaluable to the preservation of French artistic heritage. The Revolution irrevocably altered the art world, favoring propaganda and morally uplifting themes, embodied by the new Neoclassical aesthetic, over the playful sensuality of Rococo, rendering his once-celebrated style seemingly anachronistic, and marking the end of an era. It’s a somber reminder of how quickly artistic fortunes can change with political winds, but also a testament to his enduring dedication to art itself, regardless of personal gain. I find this turn in his career particularly poignant; a master of delight becoming a custodian of cultural heritage.

The "Band of Noir" Period

Interestingly, during the upheaval of the Revolution and its immediate aftermath, Fragonard experienced a lesser-known but fascinating period often referred to as his "Band of Noir" (Black Band) or "Fantasy Figures" period. Here, he produced a series of portraits and genre scenes characterized by darker, more somber palettes and often more intense, almost melancholic, expressions. These works, stripped of the Rococo's characteristic pastel hues, reveal a profound emotional depth and a responsiveness to the changing psychological landscape of his time, showcasing a side of Fragonard rarely associated with his more famous, joyous canvases. I see these as his silent commentary on a world turned upside down, a reflection of the tumultuous internal and external shifts of the period, demonstrating his artistic adaptability even in the face of profound personal and societal change. It’s a powerful reminder that even the most lighthearted artists can delve into profound seriousness when the world demands it.

His later years were marked by a quiet decline, overshadowed by the changing artistic tides and the trauma of the Revolution. He died in Paris in 1806, his vibrant Rococo style largely forgotten by a public captivated by the grandeur of Empire style and Neoclassicism. However, his legacy was not lost. His rediscovery in the 19th century, particularly by astute art historians and collectors, cemented his posthumous status as a foundational figure in French art history, and a crucial precursor to later art movements concerned with light, color, and expressive brushwork, demonstrating the enduring cyclical nature of artistic appreciation and influence. This cyclical nature of art history is a fascinating thing to observe; what is dismissed today often becomes revered tomorrow. It’s a testament to the fact that true artistic genius often finds its audience, eventually.

The Fête at Saint-Cloud

Among Fragonard's large-scale fête champêtre paintings, The Fête at Saint-Cloud (c. 1775-1780) stands as a vibrant testament to aristocratic leisure and public festivity. The painting depicts a bustling open-air festival in the meticulously manicured gardens of the Château de Saint-Cloud, filled with elegantly dressed figures enjoying games, music, conversation, and various social interactions. It masterfully captures the effervescent spirit of both public and private festivities of the era, showcasing Fragonard's extraordinary ability to manage complex compositions with numerous figures and intricate groupings while maintaining an overriding sense of lighthearted charm and dynamism. The painting's expansive landscape and lively crowd scenes highlight his mastery of depicting atmospheric effects, the interplay of light and shadow, and the joyous energy of collective merriment, making it a compelling snapshot of 18th-century French social life. Look closely, and you'll find charming vignettes: couples flirting, children playing, vendors selling their wares—each figure contributing to the bustling tapestry of a truly vibrant scene, revealing Fragonard's keen eye for social observation. It’s a masterpiece of organized chaos, where every detail adds to the overall joyous energy, making it a truly immersive experience.

The Love Letter

The Love Letter (c. 1770) is another exquisite example of Fragonard's intimate genre scenes, depicting a young woman caught in the act of writing or perhaps secretly receiving a love letter. The painting is characterized by its delicate palette, fluid brushwork, and the tender, almost conspiratorial atmosphere that draws the viewer into the private world of the sitter. Her absorbed expression, framed by the soft, diffused light, emphasizes the privacy and emotional intensity of the moment, suggesting a world of hidden sentiments and romantic longing. This work perfectly embodies the Rococo fascination with romantic intrigue, sentimental narratives, and the nuanced emotional landscapes of 18th-century individuals, offering a captivating and empathetic glimpse into their personal lives. The tender light and the subject's absorbed expression create a compelling intimacy, inviting the viewer to speculate on the secrets held within the letter, showcasing Fragonard's talent for narrative suggestion. This ability to imply a rich inner world with a single, perfectly captured moment is a hallmark of his genre scenes. It's a subtle form of storytelling that engages the viewer's imagination, a quality I find particularly compelling in his work, a true masterpiece of emotional subtlety.

Key Characteristics of Rococo Art

To better understand Fragonard's place and truly appreciate his genius, I think it's incredibly helpful to outline the defining features of the Rococo movement. By examining these characteristics, we can see how Fragonard both embraced and elevated the stylistic innovations of his era:

Characteristic | Description | Example in Fragonard's Work |

|---|---|---|

| Delicacy & Lightness | Soft colors, graceful lines, and a general air of elegance and refinement. Often characterized by a lighthearted mood and a rejection of Baroque grandeur. | Pastel hues in The Swing, the ethereal atmosphere in The Bathers, and lighthearted themes. |

| Ornamentation | Elaborate, often asymmetrical decoration, inspired by natural forms like shells (rocaille), flowers, and foliage, creating a sense of organic movement. This extended to architecture, interior design, and decorative arts. | Lush gardens, intricately carved furniture, and decorative elements in The Progress of Love series and his genre scenes. The delicate framing and rocaille motifs in many of his canvases, reflecting the widespread influence of the style in interior decoration and furniture. |

| Asymmetry | A significant departure from the strict symmetry and balance of Baroque, favoring playful, curvilinear forms and dynamic, often unbalanced compositions. | The off-center, dramatic action and swirling drapery in The Swing perfectly exemplify this principle. The dynamic interplay of figures in Blind Man's Bluff further showcases his innovative use of unbalanced compositions to create a sense of natural movement and spontaneity. |

| Themes of Love & Fête Galante | A strong focus on romantic encounters, mythological love stories, amorous dalliances, and especially the fête galante – idealized outdoor gatherings of elegantly dressed figures. This genre captured moments of aristocratic leisure and flirtation. | The Bathers, The Progress of Love series, and Blind Man's Bluff are prime examples. His numerous depictions of lovers and intimate scenes. |

| Intimacy & Sensuality | Art designed for private salons and boudoirs rather than grand public spaces, promoting a sense of personal connection, often with a hint of eroticism or flirtation. | The secretive nature of scenes in The Bolt and the playful suggestiveness of The Swing. The tender gaze in The Music Lesson. |

| Pastoral Scenes | Idealized depictions of rural life, often featuring shepherds, shepherdesses, and leisurely activities in luxuriant, dreamlike landscapes. These scenes offered an escape from urban life and its rigid social structures. | Many of his landscape and genre paintings, such as A Young Girl Reading, often incorporate idyllic natural settings, creating a sense of tranquil escape. |

| Chinoiserie & Exoticism | A fascination with East Asian motifs and imagery, incorporated into decorative arts, fashion, and sometimes painting, reflecting a taste for the exotic. This often manifested in whimsical, imagined scenes rather than accurate depictions. | While less central to Fragonard's main body of work, Rococo artists often incorporated these elements in decorative commissions, which subtly influenced broader artistic tastes. For Fragonard, elements like fanciful pagodas, exotic birds, or draped fabrics with oriental patterns might occasionally appear in decorative schemes or as subtle decorative elements within his genre scenes, reflecting the broader Rococo trend for imaginative "Orient-inspired" flourishes, adding a touch of whimsical fantasy to the overall aesthetic. This trend also speaks to the broader curiosity about the wider world that characterized the Enlightenment era, albeit often through a romanticized lens. |

| Pastel Color Palette | A preference for soft, delicate, and often shimmering pastel colors, contributing to the overall lightness and dreamlike quality of the art. | The dominant pinks, blues, and golds in works like The Swing and The Bathers. | | Chinoiserie & Exoticism | A fascination with East Asian motifs and imagery, incorporated into decorative arts, fashion, and sometimes painting, reflecting a taste for the exotic. This often manifested in whimsical, imagined scenes rather than accurate depictions. | While less central to Fragonard's main body of work, Rococo artists often incorporated these elements in decorative commissions, which subtly influenced broader artistic tastes. For Fragonard, elements like fanciful pagodas, exotic birds, or draped fabrics with oriental patterns might occasionally appear in decorative schemes or as subtle decorative elements within his genre scenes, reflecting the broader Rococo trend for imaginative "Orient-inspired" flourishes, adding a touch of whimsical fantasy to the overall aesthetic. This trend also speaks to the broader curiosity about the wider world that characterized the Enlightenment era, albeit often through a romanticized lens. |

Frequently Asked Questions about Jean-Honoré Fragonard

What was Fragonard's relationship with the Royal Academy?

Fragonard had a complex and evolving relationship with the French Royal Academy. While he initially achieved academic success, winning the prestigious Prix de Rome and even presenting a historical painting (Coésus and Callirhoé) for acceptance into the Academy, he ultimately chose a path outside its rigid structure. The Academy, which favored grand historical and religious subjects, clashed with Fragonard's natural inclination towards lighter, more intimate, and sensual genre scenes. He largely bypassed the traditional Salon system (the Academy's public exhibitions) in favor of private commissions from aristocratic patrons. This allowed him greater creative freedom but also meant he didn't achieve the same official recognition or prestigious public commissions as academic painters like Jacques-Louis David. However, as noted, he did accept an administrative role at the Louvre later in his life, demonstrating a continued, albeit different, connection to official art institutions, showcasing his adaptability and dedication to the arts beyond personal creation. This later role highlights a pragmatism often overlooked in artists known for their joyful creations. It's almost as if he chose creative freedom over institutional recognition, a bold move for any artist. It makes me wonder about the personal sacrifices artists often make for their craft.

When was Fragonard active as an artist?

Jean-Honoré Fragonard was primarily active during the mid to late 18th century, with his most prominent and celebrated works created between the 1760s and 1780s. This period precisely coincides with the zenith and eventual decline of the Rococo art movement in France. His extensive and prolific career saw him not only adapt to, but also profoundly shape, the prevailing artistic tastes, until he was eventually challenged by the dramatic shifts in aesthetic preference and the monumental political upheaval that characterized France at the close of the 18th century. He effectively worked as a professional artist from roughly 1750 until the onset of the French Revolution drastically altered the art market and traditional patronage structures, compelling him to adapt to new circumstances and artistic demands, including a shift to administrative roles in art preservation, a testament to his resilience. It's a vivid illustration of how an artist's career can be a microcosm of broader historical change.

How did Fragonard's art reflect the changing role of women in 18th-century society?

Fragonard's art offers fascinating insights into the evolving role of women in 18th-century French society, particularly within the aristocracy and wealthy bourgeoisie. His works frequently depict women not merely as passive objects, but as active participants in flirtation, leisure, and even intellectual pursuits, as seen in A Young Girl Reading. While often presented in idealized or overtly sensual contexts, his female figures exude a sense of agency, charm, and intelligence. The private nature of many Rococo commissions, destined for boudoirs and salons, suggests a more intimate female gaze and a desire for art that resonated with women's personal lives and emotions, a subtle but significant shift from the more overtly masculine themes of the Baroque. His work, I believe, captures the spirit of a society where women exerted considerable influence in salons and private spheres, even if formal power remained largely with men, highlighting a nascent recognition of female autonomy and individual experience, and showcasing a more nuanced view of femininity than often acknowledged in art history. It's a wonderful example of how art can quietly reflect profound societal shifts.

What is Jean-Honoré Fragonard known for?

Fragonard is celebrated as the quintessential master of the Rococo style, renowned for his vibrant, sensual, and exquisitely playful paintings that encapsulate the spirit of 18th-century aristocratic France. He is particularly recognized for his exceptionally fluid and expressive brushwork, shimmering color palettes dominated by pastels yet punctuated by brilliant accents, and his captivating depictions of aristocratic leisure, romantic encounters (fête galante), and idyllic pastoral scenes. His work consistently conveys a profound sense of spontaneity, a deep understanding of light, movement, and human emotion, and a unique ability to capture fleeting moments of pleasure and intrigue. While his most famous work is undoubtedly The Swing, his artistic versatility spanned an impressive range, from lighthearted intimate genre scenes to dramatically charged, psychologically complex compositions such as The Bolt, demonstrating a profound mastery across various thematic and emotional registers. I think of him as a painter of pure delight, but with a keen eye for the underlying human drama, a true storyteller with a brush.

Did Fragonard travel outside of France and Italy?

While Fragonard's primary artistic journey included his formative years in France and a pivotal period of study in Italy (primarily Rome and Venice), there is no significant evidence to suggest extensive travels beyond these two countries. His artistic development was deeply rooted in the French Rococo tradition and further enriched by his immersion in Italian classical and Baroque art. Unlike some contemporaries who embarked on grand tours across various European capitals, Fragonard seemed to find ample inspiration and patronage within France, particularly Paris, after his return from Italy, focusing on the domestic and aristocratic scenes that defined his most celebrated work. His world was largely confined to the vibrant artistic and social circles of Paris and the Italian landscapes that deeply informed his imagination, proving that profound artistic vision can flourish within specific geographical and cultural confines. He truly mastered his chosen artistic ecosystem. It's a reminder that sometimes the deepest insights come from a focused exploration of one's immediate world.

What are some famous paintings by Fragonard?

Some of Fragonard's most iconic paintings include The Swing, The Bathers, The Bolt (Le Verrou), and the magnificent series The Progress of Love (including The Pursuit, The Rendezvous, The Declaration of Love, and The Lover Crowned, as well as the later additions Reverie and Friendship). Other notable works include A Young Girl Reading, The Music Lesson, Blind Man's Bluff, The Fête at Saint-Cloud, and The Love Letter. These masterpieces collectively showcase his unparalleled mastery of light, movement, sensual themes, and capturing the effervescent spirit of the Rococo era, offering a rich tapestry of 18th-century life and emotion, each a window into the nuanced social dynamics and individual desires of the time. It's truly a pleasure to explore the breadth of his creative output.

What were the critical reactions to Fragonard's work during his lifetime?

During his most productive years, Fragonard's work was largely well-received by his aristocratic patrons, who adored his playful sensuality, his vibrant palettes, and his ability to capture the frivolous yet charming spirit of their lives. He was highly sought after for private commissions for salons and boudoirs. However, official art critics and members of the Royal Academy often held reservations. Figures like Denis Diderot, while occasionally acknowledging Fragonard's technical brilliance, frequently critiqued the perceived frivolity and moral lightness of his subjects, advocating instead for art with more serious, didactic, or heroic themes. As tastes shifted towards Neoclassicism in the late 18th century, critical opinion increasingly turned against the Rococo, deeming it decadent and outmoded, which significantly impacted Fragonard's reputation towards the end of his active career. It’s a classic example of an artist perfectly in tune with his time, only to be out of step with the next, highlighting the unpredictable currents of artistic taste and public opinion. It makes you wonder how many artists throughout history have faced similar fates.

How did Rococo art, as exemplified by Fragonard, differ from previous styles?

Rococo art diverged significantly from the preceding Baroque style, which was characterized by grandeur, drama, and weighty religious or historical themes, often intended for public display and to inspire awe and devotion, frequently employing strong contrasts and monumental scale. Rococo, in sharp contrast, embraced delicacy, intimacy, lightheartedness, and predominantly secular themes of love, pleasure, and aristocratic leisure. Its aesthetic was markedly more ornamental, asymmetrical, and focused on a vibrant yet soft pastel color palette, creating a sense of charm, elegance, and playful sensuality perfectly suited for private aristocratic salons, as exquisitely demonstrated in Fragonard's works. The scale of the art also shifted, becoming more suited to personal contemplation rather than monumental impact. Rococo aimed to enchant and delight, emphasizing grace and decorative harmony, serving as a direct counterpoint to the severity and didacticism of its predecessor, reflecting a profound shift in societal values and patronage. It's almost as if art itself took a deep breath and decided to have a little fun after the earnest pronouncements of the Baroque.

How did Fragonard's drawings relate to his paintings?

Fragonard was a prolific and masterful draftsman, producing an astonishing number of drawings that were intrinsically linked to his painting practice. His drawings served multiple purposes: as meticulous preparatory studies for larger oil compositions, allowing him to work out poses, compositions, and light effects; as independent works of art, highly prized by collectors for their own expressive qualities; and as a means of rapid idea generation. Often executed with remarkable spontaneity in chalk, bistre wash, or sanguine, they capture movement and emotion with a directness that sometimes surpasses his finished paintings. They reveal, I think, the raw energy of his creative process and his unparalleled command of line and tone, offering a fascinating window into his artistic mind, demonstrating the breadth of his artistic talent beyond the canvas. I often see his drawings as pure expressions of his artistic thought, unburdened by the demands of a large canvas. It's where you truly see the unadulterated genius at work, without the layers of refinement.

Did Fragonard's family members also pursue art?

Yes, art was very much a family affair for Jean-Honoré Fragonard. His wife, Marie-Anne Gérard, was a talented miniature painter, and his younger sister-in-law, Marguerite Gérard, became a highly successful and acclaimed genre painter in her own right, often adopting Fragonard's intimate themes of domesticity and sentimentality, and even collaborating with him on some works, particularly in the later part of his career. Their shared household and artistic environment fostered a vibrant creative exchange. His son, Alexandre-Évariste Fragonard, also became an artist, initially working in a more Neoclassical vein but later showing clear traces of his father's expressive and dynamic style. This familial artistic legacy underscores the deep integration of art into their personal lives, highlighting a rich tradition of artistic collaboration and influence. It's truly fascinating to see how artistic talent can run so strongly through a family, a testament to the stimulating environment Fragonard cultivated. It makes me think of an artistic workshop, but filled with familial love and creativity.

What is the significance of the "secret" or "clandestine" nature in some of Fragonard's works?

Many of Fragonard's most iconic works, such as The Swing or The Bolt, thrive on a sense of secrecy, hidden glances, and clandestine encounters. This element is profoundly significant as it reflects the social mores and aristocratic amusements of 18th-century France. In a society governed by strict public etiquette, private spaces and secret dalliances offered an escape. Fragonard masterfully tapped into this fascination with the forbidden, the whispered secret, and the thrill of the hidden moment. These themes allowed him to explore human desire and passion with a heightened sense of drama and psychological tension, making his works resonate with a captivating blend of charm and subtle subversion. It’s a powerful invitation to the viewer to become a co-conspirator in the scene, experiencing the thrill of a shared secret, a truly engaging aspect of his narrative genius. It's as if he's winking at us, sharing a delicious secret from centuries past.

Did Fragonard have any notable students or collaborators?

While Fragonard's style was highly individual and deeply personal, he did have several students who carried forward aspects of his artistic legacy. Most prominent among them was Marguerite Gérard, his sister-in-law, who became a highly successful genre painter in her own right, often adopting Fragonard's intimate themes of domesticity and sentimentality, and even collaborating with him on some works, particularly in the later part of his career. His son, Alexandre-Évariste Fragonard, also became an artist, initially working in a more Neoclassical vein, but later demonstrating clear traces of his father's expressive and dynamic style. Fragonard also famously had a complex and often strained relationship with his friend and contemporary, Jacques-Louis David, who would become the leading painter of the Neoclassical era, representing a stark stylistic contrast to Fragonard's Rococo exuberance. Despite their aesthetic differences and evolving political alignments, David's intervention proved crucial in securing Fragonard's position at the Louvre during the tumultuous years of the Revolution, highlighting a professional respect that transcended their artistic rivalry and underscoring the interconnectedness of the 18th-century Parisian art world. It’s a fascinating insight into the personal and professional ties that often shape art history. It's a bit like a complex family tree, but for artistic lineages.

What painting materials and techniques did Fragonard typically use?

Fragonard primarily worked with oil on canvas, employing a highly fluid, expressive, and often spontaneous technique that frequently incorporated visible, energetic brushstrokes—a radical approach for his time. He was particularly known for his innovative use of glazes (thin, transparent layers of paint applied over a dry underlayer to enrich color and luminosity) and scumbles (thin, opaque layers of paint applied lightly to create a softened, hazy effect) to achieve his characteristic shimmering light effects and rich, vibrant colors. His palette often included delicate pastels—such as soft pinks, blues, and creams—alongside brilliant accents of rose, gold, and vibrant greens, creating a distinctive and ethereal luminosity. Beyond oils, he was a master draftsman, frequently utilizing red chalk, black chalk, and bistre wash to create both meticulous preparatory studies and strikingly finished drawings that are renowned for their spontaneity, vitality, and masterful command of line and tone. His rapid and confident execution in both media allowed him to capture the essence of a moment with remarkable immediacy and emotional depth. I always feel like I'm witnessing the very spark of creation when I see his drawings, a direct window into his artistic soul.

Where can one see Fragonard's works today?

Fragonard's masterpieces are housed in prominent museums and collections worldwide, offering numerous opportunities for art enthusiasts to experience his unique genius firsthand. Major collections can be found in the Louvre Museum in Paris, which holds significant examples of his early and mature work; the Wallace Collection in London, renowned for its exquisite Rococo holdings; the Frick Collection in New York, famously home to The Progress of Love series; the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York; and the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., among other esteemed institutions. Visiting such institutions offers an unparalleled opportunity to experience his art firsthand, allowing viewers to appreciate the delicate brushwork and vibrant colors in person. For collectors interested in contemporary interpretations of artistic beauty, exploring available pieces at [/buy] can offer a connection to the enduring spirit of artistic expression, echoing the timeless elegance found in masters like Fragonard. It's a journey that connects the past with the present, showing how beauty truly transcends time, inviting us to be part of that continuous artistic conversation. I often feel a profound sense of continuity when I stand before one of his works, knowing that others have felt the same pull across centuries.

What was Fragonard's personal life like?