Kara Walker: Her Art, Silhouettes, and Unflinching Impact

Explore Kara Walker's powerful art, from iconic silhouettes to monumental installations. Confront her critiques of race, slavery, gender, and history, and uncover her enduring legacy.

Kara Walker: The Ultimate Guide to Her Art, Silhouettes, and Enduring Impact

I'm usually someone who prefers art that offers a bit of comfort, a gentle escape from the daily grind. But then there's Kara Walker. Her work, with its stark, often unsettling silhouettes and provocative narratives, doesn't just ask you to look; it grabs you by the collar, shoves you into a corner, and demands you feel something profound, even if that feeling is a messy blend of fascination, horror, and a touch of bewilderment. Initially, I even wondered if I was 'doing art wrong' by reacting this way – turns out, I was just having a perfectly normal, albeit powerful, human encounter with genius. I remember standing in front of one of her sprawling installations for the first time, my breath catching in my throat, a strange mix of dread and awe washing over me. It felt like I'd stumbled into a secret, unsettling history lesson unfolding right before my eyes, and my art-loving brain, used to prettier things, wasn't quite ready. This visceral jolt, that mix of repulsion and magnetic pull, is precisely why her art sticks with you. As an artist myself, her ability to elicit such strong, unvarnished reactions makes me constantly reconsider the purpose and power of my own work. This kind of emotional impact often makes me think of other profound art movements, like the raw power of Expressionism, which, much like Walker's work, demands a certain kind of emotional courage. Her work refuses to be casually scrolled past; it pulls you in, whispers dark secrets, and dares you to look away. And honestly, I've come to love that friction. In a world saturated with easily digestible content, Walker's work, a searing confrontation of racial injustice and historical trauma, gender, and power dynamics, is a necessary reminder that art can, and perhaps should, make us feel something profound, even if that feeling isn't always pleasant. Ready to dive into the mind behind the silhouettes and the uncomfortable truths they reveal?

Who is Kara Walker? A Master of Historical Discomfort

So, who is the woman behind these powerful, sometimes infuriating, works? Born in Stockton, California, in 1969, Kara Walker was raised in an artistic household; her father, Larry Walker, is also a distinguished painter and art professor. This early exposure to art, combined with her innate talent for drawing and painting, and their family's move at age 13 to Stone Mountain, Georgia – a town infamous for its Confederate monument and its historical association with the Ku Klux Klan – profoundly shaped her unique artistic perspective. It’s hard to imagine growing up with that kind of historical weight right outside your door, and it makes her unflinching dive into these themes all the more understandable. I often wonder what conversations happened around their dinner table; perhaps they were filled with debates on representation or the power of visual storytelling, planting seeds for Kara's later fearlessness. Meanwhile, my own family dinners were mostly debates about whose turn it was to do the dishes – a slightly less impactful upbringing, perhaps, but just as intense in its own way!

She honed her craft through formal art education, first at the Atlanta College of Art and later at the Rhode Island School of Design. At RISD, where she earned her MFA in 1994, her now-iconic large-scale cut-paper silhouettes began to take shape, quickly garnering attention for their provocative narratives. Even before her MacArthur, her early works, like those exploring antebellum fantasies, were already generating significant buzz and challenging the art world's sensibilities with their raw, unflinching confrontation of historical narratives. She is currently a professor at Rutgers University, further solidifying her ongoing impact on the next generation of artists. Honestly, it sometimes makes me feel a bit inadequate, looking at the sheer audacity and ambition in her career trajectory! But then I remember that even feeling inadequate can be a spark for inspiration, a reminder to keep pushing my own boundaries, much like the pieces I strive to create in my art for sale collection.

Drawing inspiration from diverse and often deeply problematic sources, such as the disturbing iconography of minstrel shows (performances that perpetuated racist caricatures through exaggerated stereotypes, often by white actors in blackface) and the exaggerated forms of antebellum caricatures (visual representations that mocked and dehumanized enslaved people through grotesque distortions), alongside the often sanitized narratives of historical chronicles, her early work immediately challenged the art world's sensibilities. For instance, in her groundbreaking series like Gone: An Historical Romance of a Civil War As It Occurred Between the Dusky Thighs of One Young Negress and Her Heart, she might take the smiling, subservient 'Mammy' figure from a historical advertisement and twist her into a monstrous, vengeful entity, or transform the idealized Southern belle into a perpetrator of violence. She meticulously researched 19th-century publications, slave narratives, and even popular novels like Uncle Tom's Cabin, absorbing the visual language and problematic stereotypes of the era. She would then profoundly subvert them in her own art through powerful exaggeration, shocking juxtaposition, and clever recontextualization of familiar imagery, effectively exposing their inherent absurdity and brutality.

Her rapid ascent and undeniable impact were recognized early on with a prestigious MacArthur Fellowship in 1997, an award often referred to as a 'genius grant,' recognizing exceptional creativity and potential. This was followed by the equally esteemed Rome Prize (1997-1998), further cementing her groundbreaking approach and the immediate, albeit sometimes controversial, resonance of her art. The controversy often stemmed from her explicit depictions of racial violence and sexual acts, with some critics arguing she re-inscribed harmful stereotypes while supporters saw it as a necessary confrontation of historical trauma. These critics, often Black artists and scholars themselves, sometimes felt that Walker’s work, with its raw and explicit imagery, risked re-traumatizing audiences or even inadvertently perpetuating the very stereotypes it sought to critique. Some voiced concern that by depicting such explicit and often caricatured scenes of Black suffering, Walker’s work, particularly when exhibited in predominantly white institutions, might inadvertently cater to a voyeuristic gaze or exploit Black pain for white audiences. Artists like Betye Saar and Howardena Pindell, for instance, have openly critiqued Walker’s approach, suggesting that her work might re-inscribe harmful stereotypes rather than subvert them for some viewers, or that it exploits Black pain for white audiences. Others questioned whether the work offered enough agency or uplift alongside its raw portrayal of trauma, or if it risked reinforcing rather than dismantling harmful stereotypes. This ongoing debate, however, only underscores the powerful and uncomfortable dialogue her art provokes.

Her subject matter? The brutal, often repressed, history of American slavery and racial stereotypes, intertwined with themes of gender, sexuality, and violence. It's heavy stuff, but delivered with a unique, almost theatrical flair that manages to be both horrifying and beautiful. I often think about how brave it must be to tackle such fraught topics head-on. As an artist myself, there's always that internal debate: do I create something comforting, or something challenging? Sometimes I just want to paint a serene landscape or a pretty flower, but Walker clearly leans into the latter, and the art world—and society at large—is richer for it because her work sparks crucial, often overdue, conversations about identity, power, and historical accountability. Her work doesn't offer easy answers; it offers a mirror, reflecting uncomfortable truths back at us. It's a reminder that sometimes, the most profound insights come from facing what makes us flinch. Speaking of mirrors, let's look at the distinctive medium through which Walker often delivers these powerful reflections: the silhouette.

The Power of the Silhouette: Shadows of a Troubled Past

Who knew a simple paper cutout could pack such a punch? It’s almost funny how a medium traditionally associated with gentle Victorian parlor games, or charming sentimental keepsakes, is utterly weaponized in Walker’s hands. She takes something so seemingly benign and infuses it with the kind of historical weight and biting social commentary that makes you wonder if those charming Victorian ancestors were secretly up to something far more sinister. And perhaps, they were.

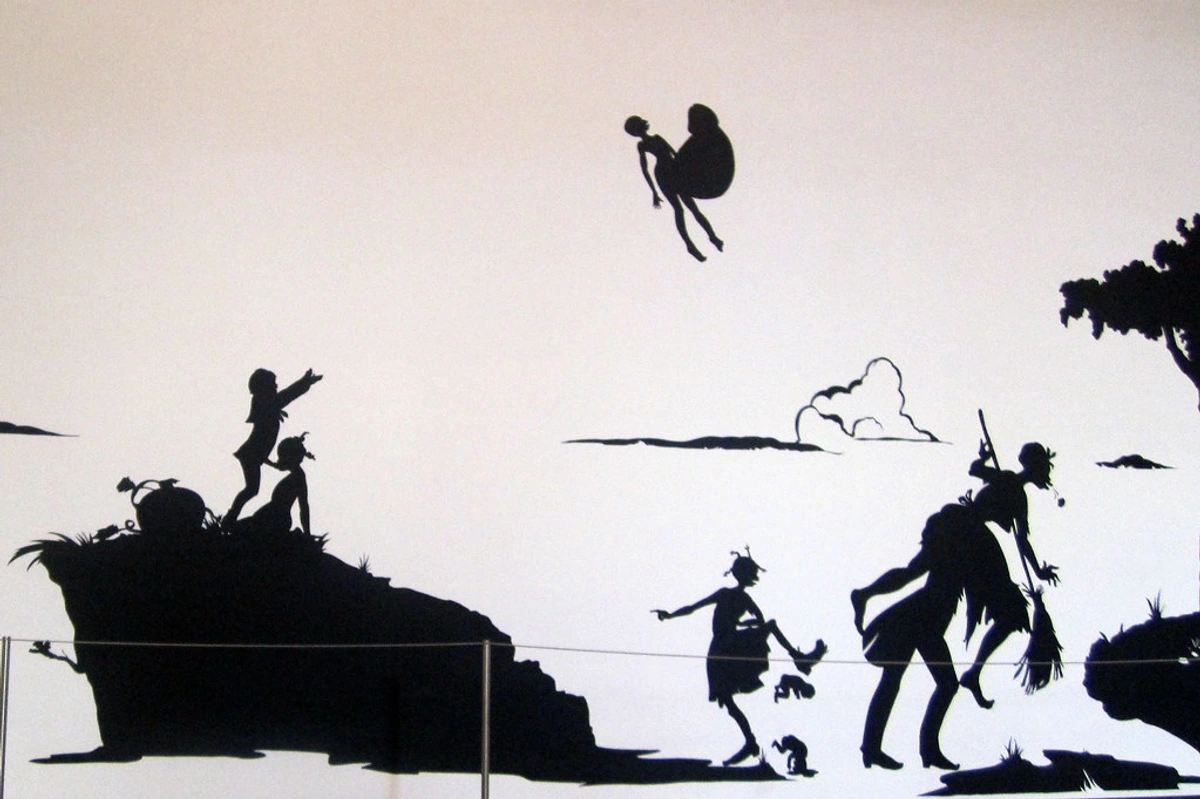

Kara Walker's signature medium is the cut-paper silhouette, a form that, to many, conjures images of innocent Victorian parlor games, genteel portraits, or charming sentimental keepsakes. Think of a genteel profile portrait of a grandparent, or a charming scene of children playing from an old book – that's the innocence she shatters. This seemingly benign medium, popular in the 18th and 19th centuries as an affordable alternative to painted portraits before the advent of photography, is utterly subverted in Walker's hands. She transforms it into a potent, almost aggressive, weapon. Often working on a monumental, room-sized scale, her process involves hand-cutting vast sheets of black paper, which are then adhered directly to gallery walls or projected to create immersive, shadow-like environments. She often begins by creating initial drawings, which she then enlarges significantly, frequently using an overhead projector, onto large sheets of paper before meticulously hand-cutting the forms.

The starkness of black on white, the absence of color or fine detail, strips away individual identity, forcing us to confront archetypes and the broader societal roles these figures embody. This flatness, paradoxically, lends a powerful psychological depth, as the viewer's own imagination is compelled to fill in the moral and emotional gaps, making the disturbing narratives even more chilling. The choice of black is particularly significant; it not only creates visual impact but also hints at themes of racial identity, the historical anonymity of enslaved people, and the stark binaries of race that have shaped American history.

A prime example is her seminal series, Gone: An Historical Romance of a Civil War As It Occurred Between the Dusky Thighs of One Young Negress and Her Heart. This lengthy, deliberately provocative title itself is a microcosm of Walker's approach, juxtaposing the brutal realities of the Civil War with a romanticized, almost salacious, narrative. The very phrasing, 'An Historical Romance' contrasted with 'Dusky Thighs of One Young Negress and Her Heart,' immediately signals her intent to subvert idyllic visions of the antebellum South to expose its hidden horrors and inherent absurdity. Within this series, she often depicts unsettling domestic scenes, grotesque figures engaged in violence or explicit sexual acts, and absurdly distorted caricatures—like those with exaggerated lips or contorted limbs. Imagine figures flying through the air, or a woman giving birth to a demon, all rendered in stark black paper. It immediately disarms and unsettles the viewer, exemplifying her use of fragmented narratives and unsettling imagery.

This choice of medium is brilliant because it taps into a shared visual history while simultaneously subverting it. The anonymous, generic nature of the silhouette allows for archetypes to emerge, representing not just individuals, but entire societal roles and power dynamics. When I look at them, it's like watching a shadow play unfold, but the shadows are alive with the ghosts of history, acting out scenes that are both familiar and shockingly surreal. As an artist who sometimes struggles with the boundaries of my own medium, Walker's fearless expansion of the silhouette into monumental installations constantly pushes me to think bigger, to consider how the simplest materials can convey the most profound truths. Honestly, sometimes I just want to draw a straight line, and she's out here telling epic, terrifying stories with a pair of scissors and some paper. The sheer amount of painstaking cutting, the patience, the dedication... it almost makes my hand cramp just thinking about it, and I only draw! Makes you think, doesn't it?

The audacity of her silhouettes, and the scale to which she takes them, sets the stage for even grander, more audacious works, like her monumental sugar sculpture.

“A Subtlety, or the Marvelous Sugar Baby”: A Sweet and Bitter Reflection

Perhaps Kara Walker's most famous and ambitious installation was A Subtlety, or the Marvelous Sugar Baby (2014) at the former Domino Sugar Factory in Brooklyn, New York. This monumental, sugar-coated sphinx-like sculpture was 75-foot long and 35-foot high, meticulously crafted from unrefined brown sugar, and often interpreted as a contemporary 'mammy' archetype posing unsettling riddles about historical memory and exploitation. It served as a powerful commentary on the history of sugar production, slavery, and global trade. This connection explicitly highlighted the brutal triangular trade routes that linked Europe, Africa, and the Americas, where enslaved people were forcibly transported to fuel the insatiable demand for commodities like sugar, tobacco, and cotton. The immense scale of the sculpture, set within the cavernous space of the factory, further emphasized the overwhelming weight of this history.

The child figures, sticky with molasses, powerfully symbolized the exploitation of child labor and the innocent lives consumed by the brutal sugar industry, adding a chilling dimension to the work's critique. Beyond its staggering visual scale, the air within the decaying factory was thick with the cloying sweetness of sugar, an almost nauseating sensory overload that heightened the work's critical message about the bitter human cost behind our most common commodities. I can almost smell the cloying sweetness, and honestly, it makes my teeth ache just thinking about it! It was a staggering sight, both literally and figuratively, and drew massive crowds before the factory's eventual demolition later that year due to gentrification and urban redevelopment, adding a layer of poignant ephemerality to the work, as if history itself was being erased for new, shinier narratives.

I remember seeing images of it and feeling a deep sense of awe and sadness. But beyond its immense scale and the bitter history it represented, the public's interaction with A Subtlety added another layer of unsettling commentary. People touched it, licked it, even took pieces of the melting sugar, inadvertently echoing the very themes of consumption, exploitation, and the ephemeral nature of history the artwork sought to critique. It was a bizarre, almost comical, and deeply unsettling spectacle: people consuming the very embodiment of exploitation, a truly meta moment that made me question our collective historical amnesia, often over a sweet treat. The sheer audacity of creating something so massive and ephemeral, destined to slowly melt and decay, was truly profound. It’s the kind of art that makes you reconsider where your groceries come from and the human cost behind them – and maybe makes you feel a tiny bit guilty about that sugar in your coffee, or your chocolate, or anything that comes with a complex, often brutal, history. It's the kind of impactful art that always makes me think of grand, site-specific installations, perhaps even inspiring ambitious projects in my own studio someday.

Beyond the Shadows: Other Notable Works and Exhibitions

What else does an artist create when they've so masterfully redefined one medium? It's like asking a chef who's perfected pasta to suddenly bake a cake – turns out, they might just bake the best cake you've ever tasted, albeit a slightly unsettling one. While her silhouettes and A Subtlety are iconic, Kara Walker's oeuvre extends significantly into drawing, painting, film, puppetry, and bronze sculpture, always maintaining her distinctive critical edge. This evolution wasn't a departure from her core themes, but rather an expansion, a strategic choice to explore the multi-dimensional aspects of her concepts – from the dynamic narratives of film to the visceral presence of sculpture – allowing her to engage audiences on different sensory and intellectual levels. Her drawings and paintings, often less explicit than her silhouettes, use a looser, more gestural style, frequently incorporating text and collage elements to explore similar themes of racial identity and historical trauma through a more fragmented and diaristic lens. They provide a deeper insight into her thought process, functioning sometimes as studies for larger works, or as independent, potent explorations. Honestly, it makes my own creative brain feel like it's running on dial-up, just trying to keep up with the mental gymnastics required to be so brilliant across so many different forms! As an artist, seeing her fearlessly leap from two-dimensional silhouettes to colossal sugar sculptures and intricate puppetry truly pushes me to re-evaluate my own creative boundaries. Maybe that abstract painting I've been dreaming of could also be a performance piece, or perhaps a temporary installation that slowly melts away, leaving only memory, much like her sugar baby.

Her haunting film, 8 Possible Beginnings or: The Creation of African-America, a Moving Picture (2005), for instance, delves into similar themes of racial caricature and historical memory, but with the added dimension of time and movement. Shifting from the static imagery of silhouettes to a dynamic, unsettling narrative, this stop-motion animated film, with its hand-drawn elements, often evokes a dreamlike, fragmented, and deeply melancholic feeling that lingers long after viewing. The medium of film allowed her to explore themes of temporal shifts and dynamic narratives that static silhouettes could not capture. More recently, her experimental use of puppetry has appeared in performances and intimate installations, notably in works like The Katastwóf Karavan (2018), a steam-powered calliope sculpture where mechanized puppets act out unsettling scenes from American history, often accompanied by haunting, dissonant melodies. This medium allowed her to bring her unsettling characters to life in three dimensions, offering a more visceral and theatrical engagement with her themes. She has even ventured into opera, designing sets and costumes for shows like The American Soldier (2019), further proving her expansive artistic reach and willingness to push boundaries beyond conventional gallery spaces. Another notable large-scale work is Fons Americanus (2019), a towering monumental fountain at Tate Modern's Turbine Hall, which reinterprets historical monuments to critique the transatlantic slave trade and colonial power. Visually, the fountain depicts grotesque figures, some headless or deformed, with water spouting from various orifices, starkly subverting the celebratory nature of traditional public sculptures and instead symbolizing the dark, often hidden, flows of colonial history. As a monumental bronze sculpture, it offered a different kind of physical presence and permanence compared to her ephemeral sugar works, allowing for complex allegories and direct interaction with the public space, deliberately tapping into the historical association of bronze with lasting public monuments, a stark contrast to the intentional decay of A Subtlety.

Beyond these, the powerful African't series stands out—a body of layered, often fragmented imagery combining silkscreen, collage, and drawing to explore racial identity and historical trauma. Characterized by its vibrant yet unsettling palettes and intricate, symbolic compositions depicting distorted figures and scenes of racial violence, this series often incorporates elements resembling her signature silhouettes within its mixed-media framework. It offers a more chaotic, layered, and often vibrant visual language that mirrors the fragmented nature of memory and identity. While not always pure cut-paper silhouettes, the visual echoes are unmistakable, a testament to her consistent themes across evolving media. Notable exhibitions beyond her individual works include Kara Walker: My Complement, My Enemy, My Oppressor, My Love (2007-2008), a major retrospective that toured several prominent museums, and Kara Walker: A Black Hole Is Everything a Star Longs to Be (2021-2022) at the Kunstmuseum Basel.

Here's a quick overview of some of her notable works beyond the silhouettes:

Work Title | Year | Medium | Key Theme |

|---|---|---|---|

8 Possible Beginnings or: The Creation of African-America, a Moving Picture | 2005 | Film (stop-motion animation) | Racial caricature, historical memory, dynamic narratives |

Fons Americanus | 2019 | Bronze sculpture (fountain) | Transatlantic slave trade, colonial power, historical monuments |

African't series | 2004-present | Silkscreen, collage, drawing, mixed media | Racial identity, historical trauma, fragmented imagery |

She's not afraid to use humor, albeit dark and biting, to expose the absurdities and horrors of historical narratives. Her work often plays with stereotypes, twisting them back on themselves to reveal their inherent cruelty and illogicality—think of a grotesque figure in a seemingly genteel setting, or the absurd juxtaposition of historical elegance with brutal violence. It’s a bit like holding up a funhouse mirror to history: distorted, exaggerated, but revealing a painful truth. For a deeper dive into how an artist's vision evolves, exploring an artist's timeline can be incredibly insightful, much like tracing Walker's journey through different mediums and conceptual explorations.

Themes and Interpretations: Unpacking the Layers

So, what makes Kara Walker's work so profoundly impactful? Is it the sheer audacity, the uncomfortable truths, or perhaps the way she forces us to look inward? Her art is a complex tapestry woven from various challenging themes, meticulously interwoven to create a multi-layered critique and often unsettling interrogation of American history and identity:

- Race and Identity: Her work fiercely deconstructs racial stereotypes, particularly those associated with the antebellum South, by using grotesque caricatures and unsettling narratives that directly challenge comfortable perceptions. For example, her iconic silhouettes in series like

Gone: An Historical Romance...explicitly confront and subvert the racist imagery of minstrel shows. She forces us to grapple with the uncomfortable origins and persistence of racialized identity. This often leads directly to her engagement with the pervasive legacy of slavery... - Slavery and Post-Slavery Narratives: She doesn't shy away from the brutality of slavery, but she also explores its lasting legacy and how it continues to inform contemporary racial dynamics. It’s less about a historical retelling and more about how history lives in the present, made palpable through visceral, often disturbing, scenes that force viewers to confront uncomfortable truths.

A Subtlety, or the Marvelous Sugar Babystands as a powerful testament to the ongoing legacy of slavery in global commerce, linking past exploitation to present-day consumption. If you're interested in how art intersects with historical events, our history of art guide offers a broad overview of art through the ages, showing how artists across time have grappled with their contemporary realities. And within these historical and racial contexts, her work unflinchingly examines... - Gender and Sexuality: Walker often depicts provocative and violent sexual acts, challenging the idealized notions of womanhood and exploring the intersection of race, power, and sexual violence. Her early works, especially, frequently depict explicit and disturbing sexual encounters that expose the historical vulnerabilities and exploitation of Black female bodies, often with a raw, confrontational honesty that subverts traditional portrayals. Her approach often aligns with feminist art critiques by giving voice to historically marginalized experiences and challenging patriarchal narratives.

- Power Dynamics: Her art consistently questions who holds power, who is oppressed, and how narratives are constructed and controlled. This is revealed through master-slave relationships, sexual encounters, and historical allegories that expose imbalances. The very act of touching and consuming

A Subtletyby the public, as mentioned, unwittingly underscored the themes of exploitation and power dynamics inherent in sugar production. - The Unreliable Narrative: By blending historical fact with fiction, myth, and satire, Walker highlights the subjective nature of history itself. She achieves this by weaving fragmented historical documents and caricatures, then twisting them to reveal uncomfortable insights. It's a profound questioning: whose narratives are privileged and whose are silenced? She actively invites us, the viewers, to critically examine our own historical understandings and biases. Think about a family story passed down through generations – how much does it change, and whose perspective is amplified? Walker does this on a grand, societal scale, akin to how a family story can subtly shift over generations, amplifying certain voices while others fade.

- Memory and Forgetting: Walker's work frequently engages with how historical trauma is remembered, repressed, or collectively forgotten, often through revisiting and re-framing difficult past events. For instance, her use of historical caricatures and narratives in her silhouettes forces a re-engagement with uncomfortable truths that society might prefer to forget, making the forgotten visible once more. This active re-memory is a central tenet of her work, pushing against collective amnesia.

Honestly, when I first started grappling with Kara Walker's work, I felt a bit overwhelmed, like trying to untangle a very complex knot. It seemed like every time I thought I'd grasped a meaning, it would shift, morph, and reveal another uncomfortable truth. It's the kind of art that makes you feel like you need a history textbook, a therapy session, and a strong cup of coffee all at once. It's why her work generates so much discussion—and sometimes, controversy. That's the sign of truly powerful art, I think; it doesn't just decorate a space, it occupies your mind, demanding constant re-evaluation. And it is precisely this unflinching complexity and deliberate discomfort that cements her profound and enduring legacy.

Kara Walker's Legacy and Impact: Why She Matters Now

Kara Walker's influence on contemporary art is undeniable. She paved the way for other artists, particularly those exploring themes of race, history, and identity, to approach difficult historical and social themes with boldness and innovation. Her uncompromising vision has earned her numerous accolades, including the aforementioned MacArthur Fellowship, election to the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and the prestigious Rome Prize (1997-1998). Her ongoing role as a professor at Rutgers University also ensures her direct influence on the next generation of artistic voices, profoundly impacting academic discourse and critical theory around race, identity, and representation in art. Her work is a constant point of reference in discussions on intersectionality, postcolonial theory, and the politics of visual culture, often serving as a catalyst for new scholarship. Beyond academia, her work has significantly influenced curatorial practices, prompting museums and galleries to re-evaluate how they exhibit difficult histories and engage with identity politics beyond traditional boundaries, often leading to more daring and inclusive programming. She is also a highly sought-after and collected artist, with her works commanding significant attention in the global art market, further cementing her influence and impact.

Her work is a cornerstone of identity politics in art, challenging viewers to confront narratives of race, gender, and power in ways previously unexplored or deemed too provocative. She has profoundly impacted artists working in installation, performance, and narrative art, encouraging a more critical and confrontational approach to history. Her influence can be seen in the work of contemporary artists like Toyin Ojih Odutola, who similarly explores identity and narrative through drawing, or Fahamu Pecou, whose work often recontextualizes historical imagery to comment on racial identity in modern society. She really raises the bar, doesn't she? Her continuous presence in major international exhibitions and retrospectives further solidifies her place as a pivotal figure.

Her work remains profoundly relevant today, as conversations around racial justice, historical revisionism, and systemic inequality continue to dominate headlines. Critics sometimes argue her work perpetuates stereotypes by visually re-inscribing them, while supporters contend she subverts them to expose deeper truths by showing their absurdity and brutality. This ongoing debate itself underscores her profound influence and the discomfort she deliberately provokes in the service of critical dialogue. She doesn't just show us the past; she shows us how the past continues to shape our present, sometimes in ways we'd rather ignore. This kind of art, art that makes you think deeply, is invaluable. It’s the kind of artistic dialogue that inspires artists like myself to create works that resonate, pushing boundaries and sparking conversations, much like the pieces I strive to create in my art for sale collection. Perhaps one day, I'll be able to visit 's-Hertogenbosch and reflect on her work at a major institution, perhaps even our Den Bosch Museum, taking in her influence right there in my own artistic backyard. It’s inspiring to think that the ripples of her audacious work can reach even a small, quiet studio like mine, urging me to keep pushing my own creative boundaries.

FAQ: Your Burning Questions About Kara Walker

Still pondering Kara Walker's profound impact? Here are some of the questions I often hear, and my thoughts on them:

What is Kara Walker most known for?

She is most known for her large-scale cut-paper silhouettes that depict provocative and often disturbing scenes related to the history of slavery, race, and gender in the American South. Her monumental sugar sculpture, A Subtlety, or the Marvelous Sugar Baby, is also highly recognized.

What themes does Kara Walker explore in her art?

She explores complex themes such as race, gender, sexuality, violence, power dynamics, American history (especially slavery), the construction of identity, and memory and forgetting. She often critiques historical narratives and racial stereotypes, subverting them to expose their absurdity and brutality.

Why does Kara Walker use silhouettes?

She uses silhouettes because they evoke a sense of historical quaintness while also allowing for anonymity and generalization, making the figures archetypal rather than specific individuals. This technique allows her to explore broad historical narratives and stereotypes in a stark, impactful way, forcing viewers to fill in the details with their own interpretations and biases. The choice of black silhouettes also powerfully signifies themes of racial identity and historical invisibility.

How does Kara Walker create her large-scale silhouettes?

Kara Walker typically uses black cut paper for her silhouettes, often working on a large scale, sometimes creating immersive, room-sized installations. She often begins by creating initial drawings, which she then enlarges significantly, frequently using an overhead projector, onto large sheets of paper before meticulously hand-cutting the forms. She employs traditional cutting techniques but subverts the genteel associations of the medium by depicting provocative, often violent or satirical, scenes.

What is Kara Walker's artistic process beyond silhouettes?

Beyond her iconic silhouettes, Walker's process incorporates drawing, painting, film, puppetry, and bronze sculpture. For her films, she often uses stop-motion animation with hand-drawn elements, sometimes accompanied by haunting soundscapes. Her large-scale installations, like A Subtlety or Fons Americanus, involve extensive planning, material research (e.g., sugar for the sphinx, bronze for the fountain), and collaboration with fabricators to realize her ambitious visions.

Is Kara Walker's art controversial?

Yes, her art is often controversial due to its provocative subject matter, including depictions of violence, sexual acts, and racial caricatures. She challenges viewers to confront uncomfortable truths, which can lead to strong reactions and debates about representation, historical trauma, and artistic responsibility. Critics sometimes argue her work perpetuates stereotypes by visually re-inscribing them, while supporters contend she subverts them to expose deeper truths by showing their absurdity and brutality.

How has Kara Walker influenced contemporary artists?

Kara Walker's bold and uncompromising approach has profoundly influenced a generation of contemporary artists, especially those addressing themes of race, gender, history, and identity. She demonstrated that art can be a powerful tool for confronting difficult historical narratives and systemic injustices, pushing boundaries in terms of subject matter, medium, and the intentional use of ambiguity to spark critical dialogue and personal reflection. Her work opened doors for more confrontational and nuanced explorations of these sensitive topics within the art world.

How does Kara Walker use humor in her art?

Kara Walker employs dark, biting, and often satirical humor in her work to expose the inherent absurdities, cruelties, and illogicalities of historical narratives and racial stereotypes. She twists familiar imagery into grotesque or exaggerated forms, creating a jarring juxtaposition that can be both unsettling and comically provocative, forcing viewers to confront uncomfortable truths through laughter or discomfort. This use of humor serves as a powerful tool for subversion and critique.

What is the significance of the 'mammy' figure in Kara Walker's work?

The 'mammy' figure, a historical stereotype of a Black woman who lovingly cares for a white family, is a recurring and highly significant archetype in Kara Walker's art. Walker profoundly subverts this seemingly benign figure by twisting her into monstrous, vengeful, or sexually explicit entities, exposing the violent and exploitative realities hidden beneath the idealized, subservient facade. This recontextualization forces viewers to confront the racist and dehumanizing origins of the stereotype and its enduring legacy.

Where can you see Kara Walker's art?

Her art is held in numerous prestigious collections worldwide, including the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, the Tate Modern in London, the Broad in Los Angeles, and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA). She also frequently has solo exhibitions at major galleries and museums globally.

Conclusion: What Kara Walker Taught Me (and Maybe You Too)

Sitting with Kara Walker's art is rarely a comfortable experience, and I think that's the point. It's a testament to her genius that she can take something as seemingly benign as a paper cutout and turn it into a searing critique of history, a profound exploration of human nature, and a mirror reflecting our own discomforts. She doesn't just tell stories; she makes us feel them, in all their ugly, beautiful complexity.

Her work serves as a powerful reminder that art isn't always about comfort or pretty pictures. Sometimes, the most important art is the art that challenges us, pushes our boundaries, and makes us think long after we've walked away. It urges us to keep looking, to keep questioning, and to never settle for easy answers. And for that, I am profoundly grateful to Kara Walker. She taught me that sometimes, the most profound beauty is found in the raw, unapologetic truth – and that my initial discomfort was just my brain getting a much-needed workout. So go ahead, let her art grab you by the collar; seek out her work in person if you can, or spend time with images of her installations online. It might just be the jolt you need, and perhaps, the profound insight you didn't know you were missing. What kind of art truly moves you? My art, on the other hand, is more of a gentle, comforting hug for your eyeballs—but hey, there's room for both, right?