Piet Mondrian: Evolution of De Stijl, Theosophy & Enduring Art Legacy

Explore Piet Mondrian's compelling journey: from early emotive landscapes through Cubism to the profound spiritual philosophy of De Stijl's Neoplasticism. Uncover his lasting influence on abstract art, design, and universal harmony.

Piet Mondrian. At first glance, just lines and primary colors, right? I'll admit, for years, my brain had a knee-jerk reaction: 'My kid could probably do that!' (No offense to any hypothetical future prodigies, but you get the sentiment). And honestly, who hasn't felt a little pang of skepticism standing before one of his iconic grid paintings, wondering what all the fuss is about? But if we stop there, we're doing ourselves a huge disservice. We're missing a profound artistic odyssey, a relentless spiritual quest to distill the overwhelming chaos of the modern world into something pure, something universal. This journey, I promise, is far more compelling than any initial impression of simplicity might suggest. Mondrian wasn't just slapping paint on a canvas; he was a philosopher with a paintbrush, meticulously building a new visual language. His work, especially the famous De Stijl pieces, feels both incredibly simple and infinitely complex – a paradox I’ve come to really appreciate. That's precisely what we're diving into today: a personal exploration beyond the familiar grids to uncover the deep philosophy and surprising evolution that solidified Piet Mondrian's place as a titan of modern art. It’s a pursuit of fundamental truths, a journey I find myself on too, in my own way, when I'm wrestling with a new piece for my art for sale. We'll traverse his path from early, emotive landscapes to the rigorous philosophy of De Stijl, and ultimately, to his enduring, pervasive legacy across art and design.

The Genesis of a Vision: More Than Just Grids

Let's be honest, before he became the patron saint of straight lines and primary colors, Mondrian was painting trees. Yes, trees! And not just any trees; these were feeling trees, imbued with a raw, almost Expressionist energy. It's a fascinating paradox, isn't it? To think the architect of rigid abstraction began with something so organic and deeply emotive. This early period, often overlooked, is crucial because it offers a glimpse into his relentless, almost spiritual, search for structure beneath the chaotic surface of the natural world. So, no, he certainly didn't only paint grids, and his career's evolution is, for me, one of the most compelling narratives in all of modern art. Just take a moment to really look at 'Evening; Red Tree' (1908-1910). If your mental image of Mondrian is limited to geometric grids, this vibrant, stylized landscape might have you scratching your head, wondering if he fell through an artistic wormhole. This early phase, deeply rooted in the Dutch landscape, shows him wrestling with the influences of Impressionism's fleeting light – notice how he uses broken brushstrokes and vibrant hues to capture a momentary sensory experience, albeit with a deeper emotional resonance than pure Impressionism. Then there's Post-Impressionism's emotional depth, visible in the bold, almost symbolic use of color and the subjective distortion of natural forms. And especially Symbolism's quest to express inner experiences through evocative, suggestive forms. For Mondrian, Symbolism provided a powerful early framework, with its emphasis on conveying spiritual meaning and subjective realities beyond the visible world. He sought not merely to depict a tree, but to imbue it with an essence, a hidden vitality. Even amidst the swirling colors, he was already searching for an underlying rhythm, a hidden order. It reminds me a bit of looking back at my own artistic timeline and realizing how many unexpected detours and transformations occurred, sometimes in directions I never anticipated.

From Organic Forms to Geometric Deconstruction

From his expressive trees, Mondrian's relentless search for underlying order took a dramatic turn with his crucial move to Paris in 1911. As many artists discover, it was a game-changer. Escaping the somewhat provincial Dutch art scene, he found himself amidst the radical experiments of artists like Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, who were pioneering Cubism. You can almost see Cubism's tectonic influence as his forms became increasingly fragmented and analytical. Cubist techniques, particularly the simultaneous viewpoints (showing multiple sides of an object at once), the use of geometric planes to represent volumes, and a more muted, monochromatic palette, deeply appealed to his nascent desire for a structured way to deconstruct reality. He began systematically breaking down objects into geometric components, almost as if dissecting them on the canvas – moving further and further from direct representation, much like the way analytical Cubists would fragment a still life into interlocking facets. It was like he was methodically peeling back layers, trying to get to the very essence of what he was seeing – a frustrating, almost maddening, but ultimately deeply rewarding task. Honestly, it's not unlike those days when I’m struggling to find the core idea in a new abstract piece, systematically eliminating elements until something essential emerges. This intensive period of fragmentation and analysis wasn't an end in itself; it was the rigorous groundwork, the crucible that forged a more radical distillation of form and color, paving the way for the birth of De Stijl.

De Stijl: The Philosophy Behind the Grids

So, how exactly did we make the leap from those emotional red trees and fragmented Cubist still lifes to the iconic, seemingly austere grids? Was it a sudden bolt of inspiration? Not at all. It was a slow, deliberate distillation, a profound philosophical and spiritual journey that culminated in the art movement we know as De Stijl (Dutch for "The Style"). For Mondrian, this wasn't just about art; it was about addressing the "chaos of the world." Think about the early 20th century: the ravages of World War I, the accelerating pace of industrialization, the sheer upheaval of society. This was a time of immense uncertainty and perceived fragmentation. Mondrian saw this chaos manifesting in the subjective, fleeting distractions of the material realm, the superficiality of modern life, and the disequilibrium he perceived everywhere. He aimed for art that could offer a glimpse into a higher, more harmonious reality, one grounded in universal principles rather than individual perception. It’s a bit like trying to find the underlying perfect pitch in a cacophony of everyday sounds, hoping to restore some fundamental order.

The Birth of De Stijl and a Universal Aesthetic

Mondrian, alongside his collaborator Theo van Doesburg, officially launched De Stijl in 1917. They weren't just forming an art group; they were advocating for a total revolution, a universal aesthetic that would permeate art, architecture, and design. Other visionaries like Gerrit Rietveld, Bart van der Leck, and Vilmos Huszár applied these principles. Huszár, for instance, played a significant role in graphic design and the movement's journal, De Stijl, helping to disseminate the aesthetic principles beyond just painting. Bart van der Leck's early De Stijl paintings, such as "Composition 1917 No. 4 (The Cat)," demonstrate a clear move towards primary colors and simplified forms, showcasing a systematic reduction of naturalistic elements – a method that greatly influenced Mondrian's own approach to color in his mature work. They envisioned a cohesive new world where art and life were seamlessly integrated, where the principles of harmony and balance could transform everything around us.

Neoplasticism and Theosophy: A Spiritual Blueprint

Mondrian’s specific philosophical framework for this new art was Neoplasticism. In essence, Neoplasticism was his quest to express universal harmony and order through the absolute reduction of visual elements. He called it a "new plastic art" – and by "plastic," he meant the artistic capacity to shape or form elements, moving beyond mere imitation to create something entirely new and self-sufficient. He believed it transcended mere representation, using art's fundamental elements – line, form, and color – to directly express universal truths, rather than just depict objects.

This wasn't merely an aesthetic preference; it was profoundly intertwined with his deep spiritual convictions, particularly Theosophy. In the early 20th century, Theosophy, a spiritual movement blending Western esotericism with Eastern mysticism, gained significant traction among artists and intellectuals seeking deeper meaning in a rapidly changing, industrialized world. It offered a grand, unifying narrative of spiritual evolution and cosmic order, providing a philosophical bedrock for abstract artists like Mondrian who yearned to move beyond superficial appearances.

For Mondrian, Theosophy offered a lens through which to comprehend the universe's underlying spiritual laws and humanity's place within them. He was deeply influenced by esoteric texts like H.P. Blavatsky's The Secret Doctrine, which explored concepts of spiritual evolution, the intricate planes of existence (physical, astral, mental, spiritual), and the fundamental dualities of existence. He believed art could directly articulate these universal principles, revealing a deeper, harmonious reality free from the ephemeral noise of the material world.

Concepts like the "divine unity of all things," the pursuit of cosmic order, and the spiritual evolution of humanity directly informed his radical visual reduction. He saw the straight line, for example, as representing the fundamental duality of existence – the male (vertical, active, spiritual) and female (horizontal, passive, material) forces achieving spiritual equilibrium when balanced. Primary colors, for him, were the most essential, pure expressions of light and cosmic energy, cleansed of all secondary and tertiary muddiness (mixtures that he felt obscured fundamental truths). It was as if he was attempting to paint the very fabric of existence, or at least his profound understanding of it. Thinking about it now, the sheer dedication to a single, overarching philosophy is almost intimidating.

Mondrian's Core Elements: Visualizing Harmony

This philosophy led to art that was purely abstract, intentionally free from individual emotion or direct representation, stripped down to its most fundamental elements. Imagine trying to find the absolute truth in everything around you, systematically stripping away all the noise until only the bare essentials remain. That’s what Mondrian was doing, settling on:

- Primary colors: Red, yellow, and blue, meticulously purified to remove any secondary or tertiary hues. For him, these were the foundational expressions of light and cosmic energy, untainted by the subjective variations of nature.

- Non-colors: Black, white, and grey, serving as crucial contrasts and structural anchors within his compositions, symbolizing the ultimate balance of light and shadow, presence and absence.

- Straight lines: Exclusively vertical and horizontal, symbolizing universal balance, the dynamic interplay of opposing forces, and the fundamental structure of reality itself. These lines carved out space, creating a dynamic rhythm without expressing individual emotion.

These elements, in his view, were the most basic visual components, capable of expressing a universal, harmonious rhythm. It sounds incredibly rigid, I know, but there's an undeniable sense of balance, tension, and rhythm in these compositions. To achieve the crisp lines and perfectly flat planes of color, Mondrian often employed rulers and sometimes even masking tape, meticulously applying oil on canvas to ensure an objective, impersonal finish, utterly devoid of expressive brushstrokes or impasto. His process often involved multiple layers of thin paint, carefully dried between applications, to achieve the uniform, unmodulated color fields he desired, a practice that demanded immense patience and precision. This meticulousness underscored his dedication to a pure, non-subjective aesthetic.

But not everyone agreed with this rigor. Critics, like Wilhelm Fraenger in 1928, found his work to be 'coldly intellectual' and 'devoid of human warmth,' perceiving its strict geometric language as overly rigid or sterile. Other voices, particularly those within the nascent abstract art scene, lauded his radical approach for its purity and forward-thinking vision, seeing it as a necessary step towards a universal art form. For Mondrian, however, these were not limitations but liberating principles, a profound spiritual undertaking to achieve ultimate clarity. He would likely dismiss accusations of lacking emotional depth by arguing that the depth lay in the profound, universal truths he aimed to reveal, rather than fleeting individual sentiment.

The Evolution of the Grid: From Observation to Abstraction

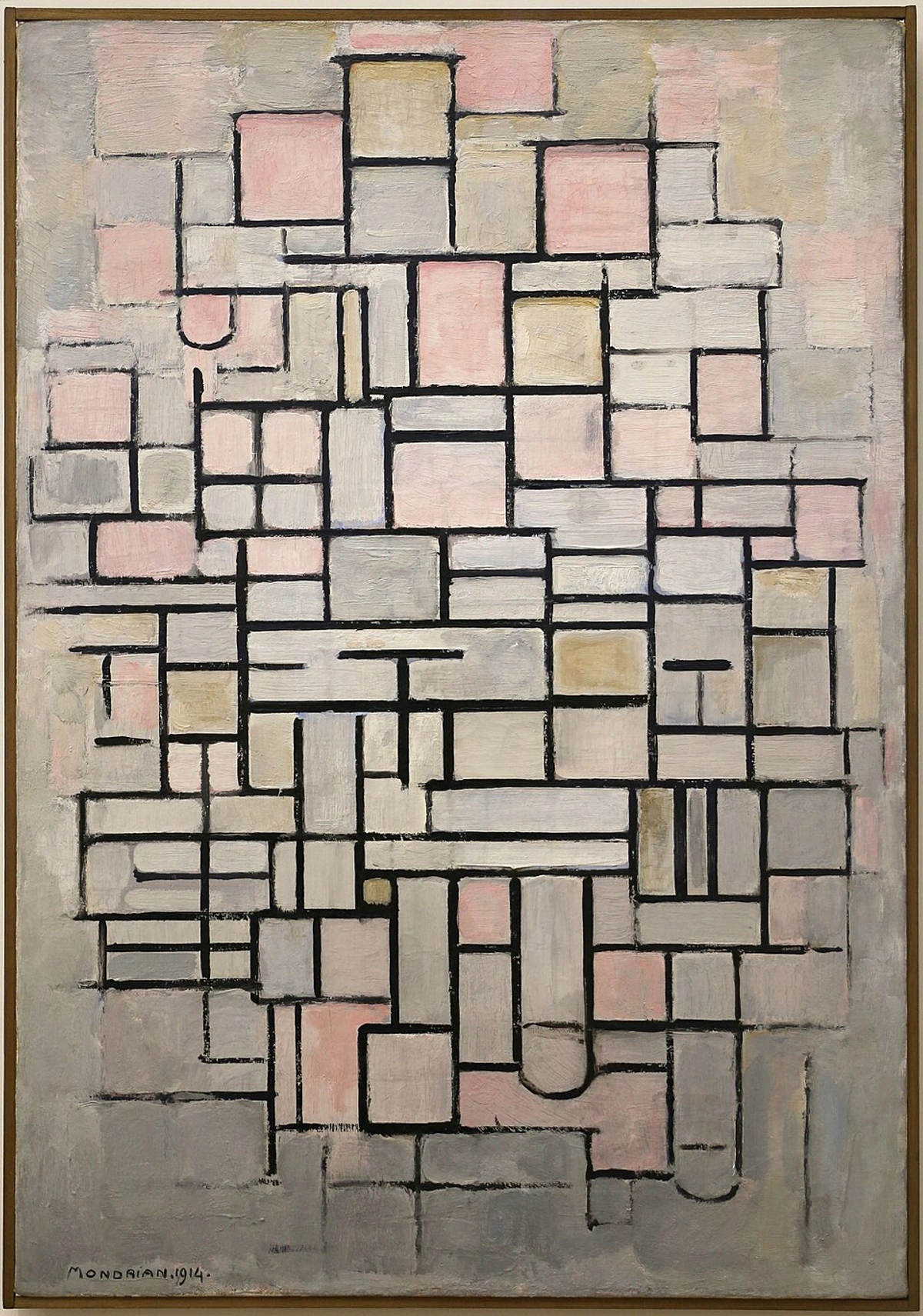

Take a look at these earlier abstract compositions, where he's still honing his vision:

This one, 'Composition No. IV,' from 1914, shows him already deep into the grid structure, but before he fully committed to just the primary colors. You can still see hints of softer hues like pink and ochre, a sort of transitional moment where he's almost there, but not quite.

Moving from that composition, notice how in this next piece, he continues to refine his approach:

![]()

Here, in 'Composition No. VII / Tableau No. 2,' you see the grid again, but with a different, still evolving palette. The subtle shifts in the proportions of the colored rectangles and the black lines, alongside the restricted color palette (compared to his earlier works), truly highlight that slow refinement towards his ultimate vision. The journey towards the quintessential Mondrian was not a straight line (ironically!), but a winding path of rigorous self-critique and experimentation. This dedication to stripping away the superfluous really resonates with me when I think about minimalism in art, or even when I'm just trying to declutter my workspace. It’s about finding clarity by shedding the non-essential.

Collaboration, Divergence, and the Path to Purity

Meanwhile, his collaboration with Theo van Doesburg, though foundational, was not without friction. Van Doesburg, a champion of a related but distinct concept he termed Elementarism, favored diagonal lines and more dynamic compositions, believing they better represented modern dynamism. Mondrian, however, saw the diagonal as disrupting the universal equilibrium he sought, finding it too emotional and individualistic – a departure from the cosmic order he aimed to depict. This fundamental philosophical difference ultimately led to a public break between the two artists in 1924, a pivotal moment for De Stijl. This division solidified Mondrian's commitment to the purity of his vision, paving his solitary path towards the iconic compositions we recognize today.

The Iconic Mondrian: Universal Harmony in Primary Hues

And so, through this rigorous process of philosophical distillation and visual refinement, we arrive at the Mondrian most people instantly recognize: those perfectly balanced, almost vibrating compositions of bold black lines and resonant blocks of red, yellow, and blue. These weren’t haphazard arrangements, decided on a whim. Oh no. Every single line, every meticulously placed color block, was chosen with absolute intention to create a dynamic, universal equilibrium – a state of active balance, not static symmetry. He was striving for an aesthetic that transcended individual cultures, personal feelings, and the fleeting trends of the day, seeking instead to reveal the fundamental, harmonious order he firmly believed lay hidden beneath reality's often chaotic surface. His ultimate purpose for art, I've come to understand, was to transform human consciousness, to help us see the underlying unity and order in the world, fostering a sense of spiritual calm and intellectual clarity.

These masterpieces, often executed in oil on canvas, ranged from intimate sizes for personal contemplation to larger works that seemed to demand an architectural presence. The scale of a Mondrian often plays a crucial role in how you experience it; a small canvas draws you into a focused meditation on balance, while a monumental piece can feel like a window onto a vast, organized cosmos, demanding engagement with the very space it inhabits. His lines, achieved with almost surgical precision using rulers or masking tape, and his flat, unmodulated color blocks, applied with meticulous care, were all about upholding a pure, objective aesthetic. You won't find impasto or expressive brushstrokes here; you encounter pure, unadulterated form and color, a testament to his belief in an impersonal, universal art. He truly believed that by stripping away the subjective, he could reveal the objective – a bold claim for an artist, wouldn't you say?

When I stand before a classic Mondrian, I don’t just see geometric shapes. I feel the tension between the horizontal and vertical, the push and pull of the colors, almost as if they're humming with a quiet, internal energy. It’s a silent dance, a profound conversation about balance and dynamism, all unfolding within the strictest, most self-imposed of rules. It forces you to consider just how potent a limited color palette can be, and the deep, underlying psychology of color in abstract art that’s at play, even in such constrained forms. For Mondrian, these carefully selected primary colors weren't just decorative; red could signify vitality, blue depth, and yellow warmth, each contributing to a universal emotional resonance. He wasn't just building a painting; he was revealing a fundamental order to the world, one precise stroke at a time. This relentless pursuit of universal harmony through such radically reduced means sparked both fervent admiration and, yes, for some, the criticism that his work could be too rigid or sterile, even 'purely decorative.' Mondrian, I imagine, would simply retort that this perceived sterility was precisely the purity required to strip away subjective distractions and reveal objective truth. But whether loved or questioned, its impact on the trajectory of art was undeniable.

Mondrian's Enduring Legacy: Beyond the Canvas

Mondrian's influence, I've found, isn't confined to canvases hanging quietly in galleries. His De Stijl principles became a veritable cornerstone for modern design in art, permeating everything from architecture to graphic design. Think of Gerrit Rietveld's iconic Schröder House, a living, breathing De Stijl manifesto with its movable walls and primary color accents, or his stark yet beautiful Red and Blue Chair, a three-dimensional geometric composition. And of course, there's the unforgettable Yves Saint Laurent dress from 1965, a direct, undeniable sartorial homage to Mondrian's grid compositions. His vision of universal harmony, expressed through basic geometric forms and primary colors, fundamentally redefined what art could be and how it could dynamically interact with our daily lives. His ideas even subtly influenced later movements like Minimalism, providing a blueprint for artists seeking purity and structural integrity through radically reduced forms.

While De Stijl was revolutionary, Mondrian’s quest didn't simply stop there. When he sought refuge in New York in the 1940s, escaping the devastation of war-torn Europe and the encroaching Nazi regime, his work absorbed a completely new, pulsating energy. His final masterpieces, like the iconic 'Broadway Boogie Woogie' (1942-43), perfectly exemplify this shift. The solid black lines of his earlier work give way to vibrant, colorful dashed lines that seem to dance across the canvas, directly evoking the city's dizzying grid system, the syncopated rhythms of jazz music he adored, and the relentless, dynamic movement of urban life. These broken lines and vibrant blocks capture the improvisation and vitality of the jazz clubs he frequented; the syncopation of the music is almost visually translated into the staggered, pulsing blocks of color. It’s a beautiful fusion of his rigorous abstraction with the undeniable energy of his new surroundings. It’s a powerful testament that even in his lifelong pursuit of universal order, Mondrian was still evolving, still finding fresh ways to express vitality within his highly structured world.

This dynamism, this sheer willingness to continually re-evaluate and adapt, is a quality I deeply admire, and frankly, one I strive for in my own abstract art. It's fascinating to note that while Mondrian was forging his unique path, other contemporaries like Kazimir Malevich were also exploring pure abstraction with their own movements like Suprematism. While both sought universal forms, Malevich's Suprematism, often exemplified by his Black Square, leaned towards spiritual liberation and the 'supremacy of pure feeling' through dynamic, often floating geometric shapes and stark contrasts. Mondrian's Neoplasticism, by contrast, focused on a more disciplined, structural balance of elements within a grounded grid, aiming for equilibrium and a universal order rather than dynamic, untethered motion. This shows a fascinating parallel quest for universal forms in a rapidly changing world. Ultimately, Mondrian showed us that profound beauty and order could be unearthed in the deepest simplicity – a profound lesson that still resonates today. When I’m working on my own canvases, even if they burst with more colors and less rigid lines than a Mondrian, I often find myself circling back to his ideas about underlying structure, impeccable balance, and the dynamic tension that he so masterfully articulated. His spirit of seeking fundamental truths through visual language is something I deeply admire and continuously strive for in my own work. His work, despite its apparent rigidity, actually evokes a sense of contemplative calm and energetic tension, inviting viewers to find their own harmony within its universal principles.

Where to Experience Mondrian

If you truly want to appreciate Mondrian’s work, seeing it in person is, for me, an absolute must. There's a tangible energy that doesn't quite translate through reproductions. Major museums worldwide proudly house his masterpieces, each offering a slightly different window into his genius. The Kunstmuseum Den Haag (formerly Gemeentemuseum Den Haag) in the Netherlands, often dubbed the "Mondrian Capital," boasts an unparalleled collection. Here, you can trace his entire career from those surprising early landscapes all the way through to his groundbreaking De Stijl canvases, including his final, unfinished, and deeply moving work, 'Victory Boogie Woogie.' This particular piece is a poignant testament to his evolving vision, even at the end of his life, pulsating with the dynamism of New York and jazz rhythms. In New York, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) proudly displays his iconic 'Broadway Boogie Woogie,' offering a vibrant encounter with his later, jazz-infused New York period – a perfect example of his ability to fuse rigorous abstraction with urban energy. And across the pond, Tate Modern in London provides a superb selection of his abstract compositions, allowing for quiet contemplation of his universal harmony and the subtle tensions within his grids. And if you happen to find yourself in the Netherlands, you might even consider visiting my museum in 's-Hertogenbosch for a different take on contemporary abstract art – perhaps you’ll find some echoes of Mondrian’s enduring legacy in my own exploration of color and form.

Frequently Asked Questions About Piet Mondrian

Q: What is De Stijl?

A: De Stijl (Dutch for "The Style") was an art movement founded by Piet Mondrian and Theo van Doesburg in 1917. It advocated for Neoplasticism, a philosophy of pure abstraction, reducing art to its most fundamental forms: primary colors (red, yellow, blue), non-colors (black, white, grey), and straight horizontal and vertical lines. Its goal was to express universal harmony and order, reflecting a deeper, spiritual reality.

Q: What is Neoplasticism?

A: Neoplasticism is the term Piet Mondrian used to describe his mature, highly abstract style. It's the philosophical and artistic framework behind his De Stijl work, emphasizing a new "plastic art" that uses only elementary geometric forms and colors to achieve a universal, rational aesthetic. It was deeply influenced by his Theosophical beliefs, seeking to use art's fundamental visual elements (form, color, line) to articulate fundamental truths, rather than merely represent objects.

Q: What were Mondrian's main philosophical influences?

A: Mondrian was deeply influenced by Theosophy, a spiritual movement that sought to understand the hidden laws of the universe and humanity's place within it. This philosophy heavily informed his Neoplasticism, as he believed that by reducing art to its most fundamental visual elements (primary colors, non-colors, straight lines), he could reveal a universal, spiritual harmony beneath the surface of the chaotic material world. Concepts like the duality of existence and cosmic order were central to his visual language. Theosophy's popularity among early 20th-century intellectuals and artists seeking deeper meaning provided a fertile ground for Mondrian's explorations into abstract art as a means of expressing universal truths.

Q: Did Mondrian only paint grids?

A: Absolutely not! While he is most famous for his grid-based compositions, Mondrian's career evolved significantly over decades. He began with traditional, representational landscape paintings, moving through phases influenced by Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, Expressionism, Symbolism, and Cubism before developing his iconic abstract style. His early works, like the vibrant "Evening; Red Tree," are a fascinating contrast to his later pieces, demonstrating his lifelong, relentless search for underlying structure and harmony that ultimately culminated in his Neoplastic grids.

Q: Why did Mondrian use only primary colors and black/white?

A: Mondrian believed that primary colors (red, yellow, blue) and the non-colors (black, white, grey) were the most fundamental and universal visual elements. Driven by his Theosophical beliefs, he sought to create an art that transcended individual subjectivity and represented universal harmony and order – a pure expression of reality, stripped of the "noise" of naturalistic color. He saw these colors as essential expressions of light and cosmic energy, and the non-colors as symbols of balance, all contributing to a universally comprehensible visual language.

Q: What materials and techniques did Mondrian use for his iconic grid paintings?

A: To achieve the incredible precision and flatness characteristic of his Neoplastic compositions, Mondrian primarily worked with oil paint on canvas. He meticulously planned his compositions, often using rulers and sometimes even masking tape to create his crisp, straight black lines. He applied his primary colors and non-colors in flat, unmodulated planes, often using multiple thin layers of paint, carefully dried between applications, to achieve a uniform, objective finish. He deliberately avoided visible brushstrokes or impasto to maintain an impersonal aesthetic, ensuring that the focus remained on the pure form and color, rather than the artist's hand, embodying his quest for universal principles.

My Final Thoughts on Mondrian

My initial skepticism about Mondrian’s work, that fleeting 'my kid could do that' thought, eventually blossomed into a truly deep, profound admiration. He wasn't just simplifying; he was passionately searching for something eternal, something profoundly spiritual, beneath the chaotic surface of appearances. It’s a pursuit that every artist, in their own way, tries to emulate – a quest for the essence, for profound clarity amidst complexity. His extraordinary journey, from those surprisingly vibrant red trees to the syncopated, energetic rhythms of New York, is a powerful reminder that true innovation often comes from the courage to strip away the unnecessary, from seeking fundamental truths through visual language, and that sometimes, the most revolutionary ideas are expressed with the simplest, most fundamental of means. His legacy continues to inspire me deeply in my own work, urging me to find that underlying structure and balance. I genuinely hope this dive into his world has sparked something similar in you too, pushing you to look beyond the surface, to find the universal in the seemingly simple. Perhaps, like Mondrian, you’ll be inspired to discover the profound harmony hidden within the structures of your own life and art, and perhaps even seek out his work in person to feel that quiet energy for yourself.