African Art's Enduring Pulse: Modernism's Deep Roots & Ethical Reflections

Uncover how African art profoundly shaped Modernism, from Cubism's revolutionary forms to Fauvism's vibrant colors. A curator's journey explores aesthetic breakthroughs, spiritual depth, and the complex ethical tightrope of cultural exchange, appropriation, and decolonization, influencing artists like Picasso, Matisse, and Basquiat.

The Enduring Pulse: African Art's Influence on Modernism – A Curator's Perspective

I still remember that jolt, that very first time I truly saw African art. It wasn't a textbook glance, mind you, but a visceral encounter that rattled my preconceived notions of art history down to their very foundations – what I now recognize as a rather beige, meticulously cataloged Western canon, if I'm being brutally honest with myself. Before that moment, I’d often found myself wrestling with precise rendering in my own early art, feeling almost trapped by the need for photographic accuracy. My artistic journey then was about mastering external reality, but something felt missing, a hollow space. My early work often felt like I was trying to perfectly replicate a snapshot, but it lacked soul, that intangible spark, that primal connection.

It was in a small, wonderfully unassuming ethnographic museum, almost hidden away, many years ago. I found myself standing before this mask, carved from dark, resonant wood – I can almost smell the earthiness and age of it now – with eyes that didn't just look at me, but seemed to bore right into something primal within. That 'primal within' felt like raw emotion, an ancestral connection, a spiritual force that bypassed the visible to speak directly to the soul. Its mouth, an untamed story waiting to be told. Forget perfect anatomical representation – a struggle I knew too well from my own early, slightly obsessive attempts at realism – this was raw energy, a spirit, an essence captured beyond the visible. And frankly, after years of trying to master precise realism, this felt like permission to breathe. It was a profound liberation, a realization that art could be about conveying a deeper truth, an inner world, rather than just mirroring the surface. In that moment, a crucial piece of the Modernism puzzle clicked into place for me, something no academic lecture, no dry historical account, ever quite managed to convey.

What if I told you that the very foundations of Modernism, the art that defined a century, were fueled by a borrowed pulse, an ancient rhythm from across the seas? We often talk about Modernism as this grand, self-contained evolution born purely in the West, and I get why. But, honestly? It’s a much richer, far more intertwined story, a truly global conversation. And the undeniable heartbeat of a significant part of that story? It absolutely comes from Africa. As a curator, my whole approach to art history is about uncovering these often-hidden dialogues, and this one, between African traditions and Western innovation, is one of the most compelling, humbling, and yes, sometimes uncomfortable, threads I’ve ever pulled on. Today, I want to trace that powerful thread, from the initial shock of personal discovery to its enduring impact on the art we see around us, critically examining the complex ethics involved. We'll journey from that initial spark of discovery, through the seismic shifts in art history it ignited, into the ethical tightropes we walk today, and finally, to its vibrant echoes in contemporary art. This journey isn't just about aesthetic breakthroughs; it’s also a deeply personal grappling with the complex ethics involved in such cultural exchanges, which includes issues of appropriation, decontextualization, and colonialism – issues that often highlight power imbalances and a lack of reciprocal understanding. And those parts are often the most uncomfortable, but perhaps the most necessary, to truly understand the story. What does it mean to be truly inspired, after all, and where do we draw the line between homage and exploitation? So, join me as we explore this conversation I've been having with myself for years, and now, with you.

Beyond Mimesis: Why Modernists Looked East and South

So, how did this profound shift occur? Why did a generation of European artists, seemingly hell-bent on breaking every rule in the academic art book, suddenly turn their gaze south and east, seeking a visual vocabulary utterly different from their own? Well, let's be real, they were desperate for something new, something real. For centuries, Western art had been chasing naturalism (the accurate depiction of nature), idealized forms, and a kind of visual 'perfection' that often meant precise linear perspective, strict classical proportions, the idealized nude, and anatomical fidelity. This pursuit, while yielding undeniable beauty, felt increasingly stifling to artists eager for a rupture, particularly as society itself was changing. Industrialization was reshaping daily life, and burgeoning interests in psychology and anthropology challenged static views of humanity, making the old ways of seeing feel increasingly inadequate for capturing the dynamism of modern life. A rising bourgeoisie sought novelty and distinction, while the rigid structures of the Salon – that official, conservative art exhibition system that dictated taste – felt utterly stifling. Imagine the stiff collars and even stiffer poses! It wasn't just about technical constraints; many felt a deep yearning for art that spoke to profound emotional truths and spiritual realities, a dimension often perceived as missing in the academic emphasis on outward appearance.

Then, like a lightning strike, they encountered African sculptures and masks. These objects were often displayed in ethnographic museums – institutions dedicated to the scientific description of peoples and cultures – collections born from colonial-era curiosity, sites of genuine discovery, yes, but let's be honest, also places of profound misinterpretation, often born from loot and conquest. Too often, these powerful objects were displayed without any context of their creators or original purpose, reducing them to mere curiosities rather than recognized masterpieces. Initially, many dismissed them as 'primitive' – a term I find reductive, infuriating, and frankly, deeply unjust, burdened with significant colonial baggage because it denied the sophistication, agency, and artistic mastery inherent in African cultures. But for burgeoning Modernists like Picasso and Matisse, these were anything but simple. They were a revelation.

What truly captivated them was a powerful, sophisticated aesthetic: a deliberate, often radical, distortion of the human form, an emphasis on symbolic meaning over literal representation, a profound spiritual resonance, and forms that were shockingly bold and direct. African art challenged their very notions of perspective, offering multi-faceted viewpoints and a lack of a fixed vanishing point (the distant point at which receding parallel lines seem to meet) – a visual simultaneity that blew open new possibilities. Imagine a face where the front and profile are compressed onto a single plane, or eyes are rendered not as an optical window, but as a piercing, geometric symbol of insight. It was an art that wasn't trying to trick the eye but to stir the soul, speaking to a deeper, spiritual truth, a kind of conceptual representation that prioritized an object's essence over its visible reality. When I'm working in my studio, trying to distill a form down to its very essence, to capture the spirit of something rather than just its surface appearance, I often think of this revolutionary shift. It’s a challenge to see past the obvious and embrace a deeper truth, much like describing a person by their character rather than just their physical features.

These potent vessels of spiritual belief, tools for ritual, or symbols of social power came from vibrant cultures across West and Central Africa. Think of the serene, often elongated faces and intricate headdresses of the Dan masks, frequently carved from dense, dark wood like iroko and central to community rites like initiation or even social control – their elegant abstraction offering a clear counterpoint to Western anatomical studies. Or consider the elegant Baule figures, known for their smooth, polished finishes, dignified postures, and elaborate coiffures, sometimes created from rich, light-colored woods as 'spirit spouses' to bring balance and well-being – their refined stillness conveying immense inner strength that Modernists admired. Then there are the geometrically daring Fang reliquary guardians, with their stylized, often angular proportions and elongated features, housing the ancestral bones of venerated elders – imbued with profound spiritual purpose, typically carved from a single block of wood, or sometimes adorned with copper and brass elements, standing as powerful protectors of lineage. These guardians, with their bold, frontal presence and conceptual rather than optical forms, were particularly revolutionary. We also see the expressive Luba statues, conveying emotion through subtle gestures and often rounded, harmonious forms in highly polished wood, serving as memory boards or symbols of leadership and fertility – their nuanced storytelling through simplified forms resonated with artists seeking expressive truth. And of course, the intricate Senufo carvings, particularly their bird figures like the poro birds, which symbolize wisdom and are vital in initiation ceremonies, with their distinctive elongated beaks and powerful stances – their dynamic yet distilled forms offering a blueprint for symbolic representation. Each piece pulsed with a different energy, a distinct cultural narrative, often carved from resonant woods like iroko or ebony, or cast in bronze, sometimes even incorporating ivory or other precious materials. This rich materiality – the deep grain of the wood, the cool smoothness of polished bronze, the weight of a stone figure, the texture of a raffia mask – spoke volumes. Their tactile presence was as captivating as their forms, inspiring a raw, unpolished approach in Western artists, tired of the illusionistic surfaces that had dominated for centuries. Beyond sculpture, the bold, geometric patterns of African textiles and the rhythmic complexity of African music and dance also offered a revolutionary departure from Western artistic conventions. The repetition and improvisation in textiles, for example, directly inspired new approaches to composition, pattern, and rhythm, not just in painting but also in early performance art and sculpture, pushing artists to think about visual fields as dynamic, broken planes or vibrating surfaces.

While our focus here is on Africa, it’s worth noting that Modernists also looked to other non-Western art forms, like those from Oceania and Mesoamerica, for similar inspiration, drawing a broader connection between disparate cultures seeking a departure from academic tradition. Crucially, the widespread dissemination of these objects, often through photographs and reproductions in journals and salons, made their aesthetics accessible to European artists far beyond the limited confines of museum walls. If you’re curious about the broader strokes of this topic, I’ve also written about understanding the influence of African art on Modernism from a more general perspective.

This embrace of non-Western aesthetics laid the groundwork for entirely new artistic languages, dramatically shaping the trajectory of movements like Cubism, Fauvism, and Expressionism. It was a shattering of old forms, a truly seismic event that echoed across studios and galleries, fundamentally altering the artistic landscape. So, how exactly did these powerful forms ignite such a radical transformation in European art? The journey often begins with a deliberate rupture, a breaking of established norms.

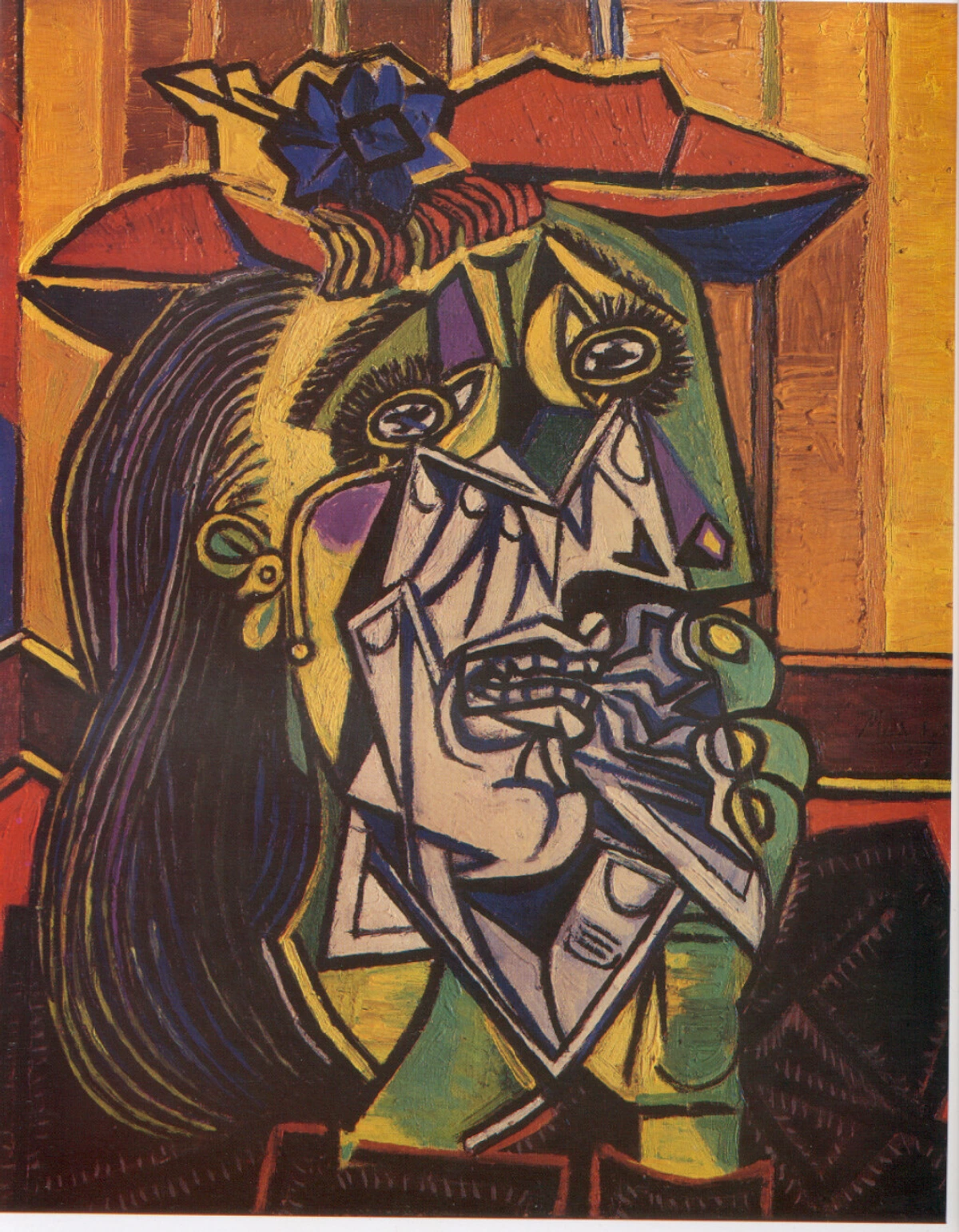

The Cubist Revolution: Picasso, Braque, and the Primal Form

Nowhere was this seismic shift more evident than in the explosive birth of Cubism. I mean, just look at it! The fragmented planes, the multiple viewpoints, the way figures are deconstructed and reassembled – it's less 'almost a direct conversation' and more like a shouted revelation, deeply informed by the formal qualities of African masks and sculptures. Pablo Picasso, in particular, was famously affected after seeing African art at the Trocadéro Museum in Paris, a moment I can only imagine experiencing. He reportedly saw powerful masks from cultures like the Fang and Dan, which resonated deeply with his desire to break down and reassemble forms. This encounter was pivotal for works like his groundbreaking Les Demoiselles d'Avignon (1907), where the faces of some figures bear unmistakable resemblances to Iberian sculpture and, crucially, to African masks, shattering traditional European representation. While Picasso also drew from Iberian sculpture and ancient Greek forms, it was the raw power and radical abstraction of African masks that truly unlocked his vision, pushing him far beyond traditional European representation. And it wasn't just Picasso; his close collaborator, Georges Braque, was simultaneously grappling with similar questions of form and space, finding parallel inspiration in their bold linearity and simplified structures, which helped lay the groundwork for a new understanding of composition. Figures like André Derain and Maurice de Vlaminck, though perhaps less centrally, also engaged with these new visual languages, broadening the impact across the nascent Cubist circles, drawn to the raw, visceral qualities they offered. Derain, for example, collected Fang masks, and his early Fauvist work, though focusing on color, shows a move towards simplified, powerful forms before Cubism fully emerged. If you want to delve deeper into the artist who perhaps sparked this revolution the most, my ultimate guide to Picasso is a great place to start.

Picasso later said something to the effect of: these masks weren't just sculptures, they were 'magical objects... intercessors against everything – against unknown, threatening spirits.' It wasn't just about how they looked, but the power they embodied, the raw material, the patina, the very process of carving life from wood. Imagine the impact of seeing a figure where the nose isn't just a nose, but a sharp, geometric plane, or eyes aren't round and soft but angular and piercing. This kind of conceptual representation, where an object’s essence is conveyed through simplified, exaggerated forms – a sort of 'multiperspectival truth,' allowing multiple facets of an object to be seen at once – was truly revolutionary for him, a stark departure from the optical representation that had dominated Western art. When I'm wrestling with a canvas in my studio, trying to distill form to its essence, to capture the raw truth of a subject without getting bogged down in superficial details, I often think back to how artists like Picasso and Braque must have felt in that moment of profound revelation, discovering a visual language that resonated so deeply with their own artistic quests. Talk about a lightbulb moment! This structural deconstruction wasn't merely aesthetic; it was an attempt to capture a deeper reality, a move mirrored in the profound spiritual functions of the African art itself. If you’re really digging into this, I highly recommend checking out my ultimate guide to Cubism for a deeper dive into the movement itself. How deeply can an external form shape an internal artistic revolution? In my own journey with abstract art, that pursuit of stripping away the superfluous to find the core truth of a subject is a constant, vital challenge, a whisper of those ancient forms guiding my hand.

Emotional Resonance: Fauvism, Expressionism, and Beyond

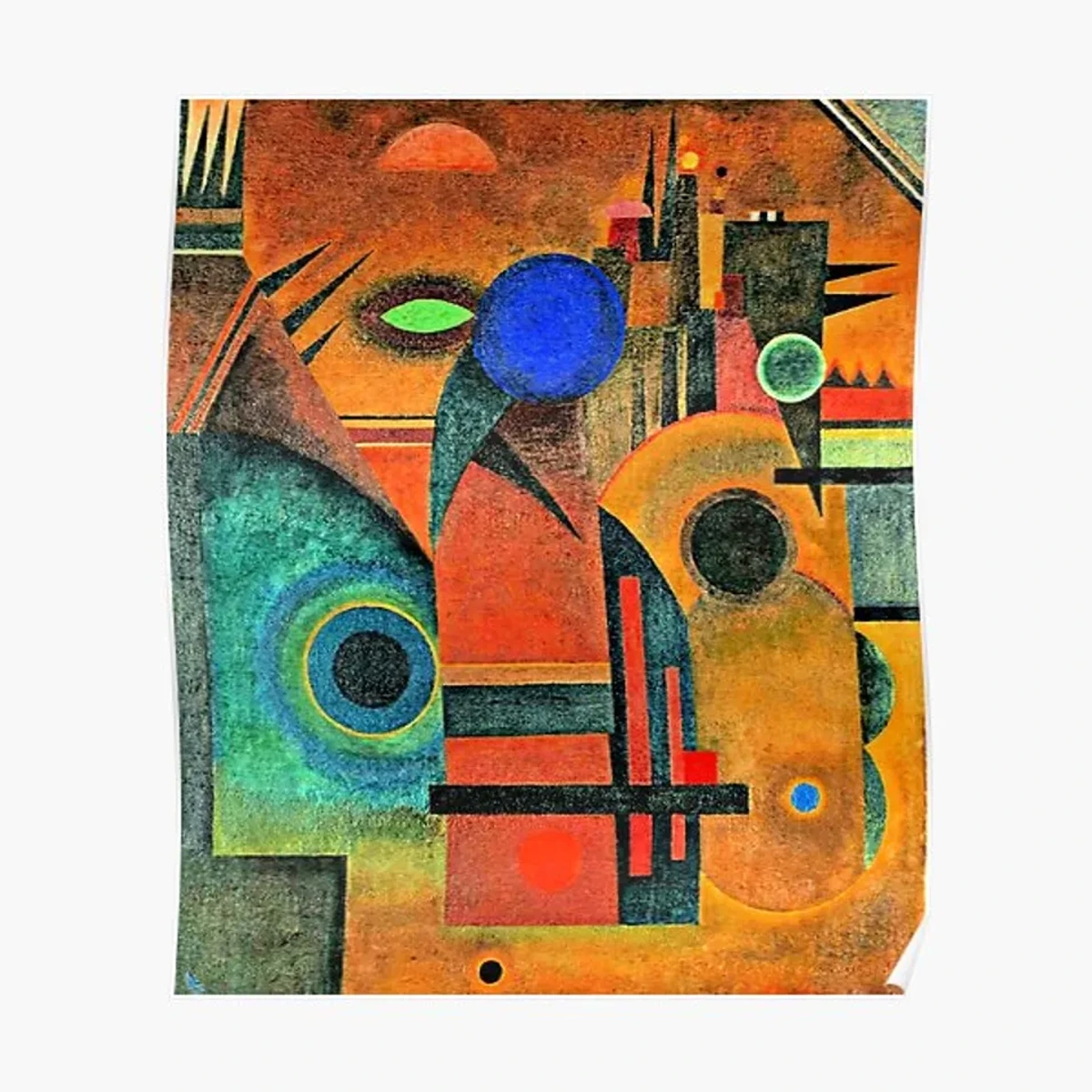

But the influence wasn't confined to dissecting form; it also ignited a fire of emotion and spiritual intensity in subsequent movements. While Cubism fractured reality to reveal its structural truths, other artists sought to express its feeling, its inner world. What about the explosion of color and feeling that came with Fauvism (a movement characterized by bold, non-naturalistic color) and Expressionism (focused on conveying subjective emotion and inner experience)? These movements, too, found profound echoes in African art, shifting the focus from structural deconstruction to emotional intensity and spiritual vibrancy. Henri Matisse, a titan of Fauvism, was also deeply influenced. While Picasso was fascinated by the formal breakdown of figures, Matisse seemed drawn to the bold contours, simplified forms, and vibrant, non-naturalistic colors that African (and, to a lesser extent, Oceanic) art showcased. This included the flattened planes and bold outlines found in some African textiles, painted surfaces on masks, and carved figures, which provided a striking aesthetic template. His figures often possess an elegant distortion, a rhythmic simplification that echoes the powerful, yet refined, presence of many African sculptures. Matisse saw a directness, an immediacy that European art, perhaps, had lost in its pursuit of illustrative perfection. He sought the spiritual power, the 'mana' if you will, that these forms embodied, often manifested through their striking color combinations and simplified palettes – colors that seemed to vibrate with an inherent energy, a stark contrast to the muted tones of traditional academic painting. You can see this clearly in works like his famous La Danse, which pulses with a vibrant, simplified energy, a primal dance that transcends mere representation, directly inspired by the dynamic energy and communal spirit of African dance and ritual. If you want to delve deeper into his oeuvre, my ultimate guide to Henri Matisse is a good resource, and you can explore more about the movement itself in my ultimate guide to Fauvism and even how they understood color theory.

Similarly, the German Expressionists like those in the Die Brücke and Der Blaue Reiter groups, as well as broader German Expressionist tendencies, were utterly captivated by the raw emotional intensity and spiritual power they perceived in African art. They weren't just looking at the aesthetics; they were grasping for the very techniques and materials – the direct carving of wood, the stark application of pigments, the bold, often symbolic use of color – that conveyed such potent feeling. This included the very texture and physicality of the African objects – the rough-hewn surfaces of wood carvings, the worn patina of ceremonial masks, the raw impression of material straight from the earth. These qualities directly inspired a more immediate, less polished approach to paint application in their own works, leading to techniques like visible, impasto brushstrokes and a valuing of the material presence of paint over smooth illusion. They sought to convey inner experience rather than external reality, and African art, particularly the more angular, powerful masks and figures from West and Central Africa, provided a potent model for achieving this through stark forms, vivid colors, and a deliberate disregard for conventional beauty. It was a rejection of bourgeois tastes and a yearning for something more primal and authentic, a direct echo of that initial 'raw energy' I saw in that museum so long ago. The perceived ritualistic and spiritual function of these objects deeply resonated, offering a pathway to imbue art with a deeper sense of purpose and connection to fundamental human experience, a profound search for authenticity that mirrored their own emotional turmoils and societal critiques. If you want to explore this more, my ultimate guide to Expressionism might be a good next stop, perhaps followed by a deeper dive into texture in abstract art.

And the influence didn't stop with the big names or the loudest movements. Consider Amedeo Modigliani, whose elongated figures, with their simplified, mask-like faces and almond-shaped eyes, unmistakably channel the graceful, yet stylized, forms from the Punu or Baule peoples – an elegant echo of African portraiture, distilling human presence to its essential lines. Or think of Constantin Brancusi's relentless pursuit of simplified, elemental, totemic forms, which, while deeply personal, shares a profound kinship with the reductive power seen in many African sculptures, where an entire being is distilled to its most essential lines, a whispered secret passed down through generations. His smooth, abstracted wood and stone carvings evoke a similar primal energy to the carefully chosen raw materials of traditional African sculpture. It’s a reminder that this dialogue wasn't confined to a few titans; it infused the entire fabric of early 20th-century art, inspiring a pervasive, fundamental shift in Western artistic thought. How do we measure the echoes of a whispered truth across continents and centuries? When I reflect on my own journey, trying to find that perfect balance of expressive gesture and distilled form, I often feel this same lineage, this ancient wisdom, informing my choices.

A Curatorial Tightrope: Navigating History and Ethics

Now, from a curatorial perspective – and this is where things get a bit more nuanced, sometimes uncomfortable, and frankly, a necessary moment for self-reflection – we absolutely have to acknowledge the complex context of this exchange. While the profound artistic impact of African art on Modernism is undeniable, this powerful exchange was deeply intertwined with complex ethical considerations that we, as curators and art historians, must confront. Walking this curatorial tightrope, for me, means grappling with the heavy responsibility of presenting art history honestly, of celebrating beauty while confronting injustice. This artistic revolution wasn't without its shadows. How do we navigate the complex ethical terrain of this exchange, celebrating the breakthroughs while confronting the difficult truths?

The term 'primitivism,' used to describe this appropriation, carries significant colonial baggage. It often implied that these forms were simple or unsophisticated, rather than recognizing them as highly refined products of complex, ancient cultures with their own rich histories, philosophies, and master artists – a truly reductive and frankly, deeply unjust categorization. For instance, a sophisticated Luba memory board (lukasa), intricately carved to transmit historical narratives, might have been dismissed by Western collectors as a mere 'primitive idol' due to its non-Western origins, completely divorcing it from its profound cultural and intellectual purpose. It's almost ironic, isn't it, how the very cultures being subjugated by colonial powers were simultaneously providing the "inspiration" that revitalized Western art. This label was a tool of 'othering,' categorizing non-Western art as inherently less developed or rational, effectively denying its rightful place in a global art historical canon. A bitter pill to swallow, if you ask me.

This historical narrative also often presents these objects as mere 'artifacts' rather than 'art,' further decontextualizing them – stripping them of their original meaning, function, and cultural narratives. Modernists, in their aesthetic revolution, often extracted formal elements from African objects, stripping away not just their original meaning and function but also the underlying cultural narratives and spiritual power. Crucially, they did this largely without attribution or full understanding, and notably, without direct engagement with contemporary African artists or the living traditions that created these works, contributing to the Western tendency to view vast, diverse African art through a monolithic lens – a bit like judging all European art by looking at only Dutch still lifes, missing a huge, vibrant world of artistic expression! This historical narrative has rightly faced significant criticism from scholars and institutions challenging these colonial-era interpretations. Early scholars like Carl Einstein, and prominent collectors and dealers of the era, while acknowledging the artistic power, often framed African art through a Western, evolutionary lens, suggesting it represented an earlier, less developed stage of human creativity. This further entrenched the problematic 'primitive' label, subtly justifying a hierarchy where European art sat at the apex.

My role, and what I strive for when I consider art history, is to illuminate this complex dance. It’s about celebrating the immense, undeniable contribution of African art while also critically examining the power dynamics, biases, and sometimes outright injustices of the era. This involves grappling with debates around:

Repatriation of Objects

The urgent and ongoing discussion of returning cultural heritage to its originating communities is paramount. The recent discussions and returns of Benin Bronzes to Nigeria, for example, highlight this critical process of rectifying historical wrongs and acknowledging the rightful ownership of cultural property, which were often plundered during punitive colonial expeditions in the late 19th century. These returns are not just about objects; they're about restoring dignity and cultural narrative.

Decolonizing Museum Collections

This means actively re-evaluating and making collections more inclusive and ethically curated – a topic that feels incredibly urgent today, and one I've touched upon in the enduring influence of indigenous art on modern abstract movements. It's about shifting narratives and ensuring diverse voices are heard.

Fostering Collaborative Exhibitions

Ensuring that African voices and interpretations are centered, and that exhibitions are co-created with, rather than imposed upon, originating communities. This promotes true dialogue and respectful engagement.

Recontextualization

Presenting objects not just as isolated aesthetic forms, but within the rich social, spiritual, and historical frameworks from which they emerged, often through direct collaboration with originating communities and living artists. It's about restoring meaning and purpose.

It's an ongoing conversation, one I engage with regularly, whether through exploring influences on my own artist's timeline or participating in discussions at institutions like the Den Bosch Museum. It's a tricky path, but a profoundly necessary one, to move beyond simply acknowledging influence to understanding the full cultural exchange, with all its beautiful, messy, and sometimes uncomfortable truths. And if you're ever considering acquiring art with a deep cultural history, you should certainly be aware of the ethical considerations when buying cultural art. What responsibility do we bear as custodians of cultural heritage? For me, it means constant questioning, learning, and striving to give voice where it has historically been silenced, even in my own art. I sometimes reflect on my own creative process and wonder if, in the act of simplification or abstraction, I'm inadvertently stripping away context. It's a humbling thought, a reminder to always be aware of the stories behind the forms.

The Unbroken Thread: Contemporary Echoes

The ripple effect of African art on Modernism didn't stop in the early 20th century; it continues to resonate, a vibrant, unbroken thread through contemporary art. While the historical engagement with African art by Modernists is fraught with complexity, its influence is not a relic of the past; it continues to resonate powerfully in contemporary art, inspiring new generations. Artists today still draw on a raw, expressive energy and symbolic language that, while distinct, can be seen in a lineage that traces back through Modernism to its non-Western wellsprings. Think of Jean-Michel Basquiat, for instance, whose Neo-Expressionist work pulses with a directness, layered symbolism (often drawing on African, Haitian, and street art iconography, including mask-like faces and abstract figures), and an almost primal mark-making. His intense emotionality and raw authenticity directly echo the Expressionist yearning for inner truth over external reality that was also inspired by African art. It feels like he took that initial spark the Modernists first glimpsed and amplified it for a new generation, creating a raw visual poetry that challenged the art establishment and made us look differently. If you want to dive deeper into this fascinating movement, my ultimate guide to neo-expressionism is a great place to start, or even specifically explore the work of Jean-Michel Basquiat.

And then there are artists like El Anatsui, whose monumental textile-like sculptures made from recycled bottle caps reclaim and transform materials and ancestral techniques like weaving and assemblage, creating a powerful dialogue between tradition and contemporary concerns. By repurposing everyday found objects into intricate, shimmering tapestries, he imbues them with new meaning, speaking directly to issues of identity, consumption, and history in a way that resonates with that same innovative spirit of recontextualization and material reverence. His choice of discarded bottle caps is particularly significant; it transforms objects tied to global consumerism and colonial legacies into grand statements of cultural resilience and artistic innovation, reminiscent of traditional Kente cloth or royal regalia, and echoing the collaborative workshop practices of many traditional African art forms. His flexible, flowing installations constantly adapt to new spaces, challenging fixed notions of sculpture and offering a powerful critique of Western art historical hierarchies. It’s a wonderful example of how African artists themselves engage with, and redefine, their rich artistic heritage, contributing to a broader African Modernism – a distinct, multifaceted artistic movement that developed across the continent, often in dialogue with global trends but rooted in unique African perspectives and traditions, rather than simply being a source of influence for the West. This active reinterpretation by African artists underscores the continuous vitality of these traditions, moving beyond the historical, often one-sided, engagement of early Modernists to create a truly global, inclusive art history.

For me, as an artist exploring abstract art, this dialogue is incredibly important. It reminds me that artistic innovation rarely happens in a vacuum. It's a grand conversation across cultures and centuries, a constant push and pull of ideas, forms, and philosophies. When I'm in my studio, experimenting with new techniques or playing with color and composition, I'm constantly thinking about how to convey emotion and meaning without literal representation. When I choose a particular shade of ochre, for instance, I'm not just thinking about its visual appeal, but about the earthy resonance I first felt in that museum, a resonance I now consciously seek to evoke in my own palette. Or when I strip a form down to its geometric essence, I feel a kinship with those ancient carvers, aiming for that same raw energy and spiritual depth. It's a journey, always – and it’s a profound moment, isn't it, when you really see how these threads connect across time and space? It makes you feel the universal pulse of creativity, a beautiful, messy, and constantly evolving story.

So, next time you're in a museum, perhaps even my own at Den Bosch, pause. Look not just at the surface of a painting, but try to feel its pulse, its lineage. You might just find that ancient African heartbeat echoing through the canvas, a testament to art's enduring, boundary-crossing power – a whisper, perhaps, that even in our most modern expressions, we are forever connected to the deepest, most primal wellsprings of human creativity. If you're curious about my work and want to see some of these echoes for yourself, feel free to browse my art for sale.

Frequently Asked Questions About African Art's Influence on Modernism

Before we sign off and you rush to the nearest gallery, let's tackle a few burning questions that often arise when we talk about this fascinating cross-pollination. It's a lot to take in, I know, so think of these as little signposts along our journey.

Question |

|---|

| Was the influence of African art on Modernism purely aesthetic? |

| Which specific African art forms had the greatest impact? |

| How diverse is African art, and did Modernists engage with this diversity? |

| How did photography and reproductions facilitate the influence of African art on Modernism? |

| Is the Modernist engagement with African art considered cultural appropriation? |

| How can I distinguish between genuine appreciation and problematic appropriation? |

| What were the ethical implications of collecting African art during the colonial era? |

| What are the ethical considerations for museums displaying African art today? |

| How do contemporary African artists engage with this legacy? |

| What role did specific materials play in African art's influence on Modernism? |

| What was the role of women in traditional African art production and use? |

| How did colonialism facilitate the dissemination of African art to Europe? |

| How can I identify African art influences in specific Modernist works? |

| How can I learn more about the independent evolution of African art? |

| How can I learn more about this connection? |

Answer |

|---|

| Not at all. While formal qualities (like geometric distortion, simultaneity, simplified forms) were undeniably key, Modernists were also deeply drawn to the perceived spiritual and symbolic depth. They sought to imbue their art with similar power, authenticity, and connection to universal human experiences, moving beyond mere visual representation and into the realm of deeper meaning and emotional truth. |

| Primarily masks and figurative sculptures from West and Central Africa (e.g., from the Dan, Fang, Senufo, Luba, and Baule peoples) profoundly influenced Cubism and Expressionism. Their stylized, geometric, and emotionally charged forms provided a revolutionary new visual language. Crucially, these objects were often created for vital ritual, ceremonial, or ancestral veneration purposes, imbued with a profound function that resonated with Modernists seeking more than mere representation. |

| African art is incredibly diverse, encompassing thousands of ethnic groups, distinct traditions, styles, and materials across a vast continent. Modernists, however, often engaged with it under a generalized 'primitivism' label, primarily drawn to a limited subset of forms (mostly sculpture and masks) from West and Central Africa. They often failed to appreciate the immense cultural depth or individual artistic contexts, contributing to a monolithic, reductive view – a bit like judging all European art by looking at only Dutch still lifes. |

| Photography and various forms of reproduction (like etchings in journals or exhibition catalogues) played a critical, often underestimated, role. They allowed European artists, many of whom never traveled to Africa, to encounter and study African artworks, facilitating their widespread dissemination far beyond museum walls. These reproductions brought new visual vocabularies to artists, influencing their experimentation with form, perspective, and symbolism. |

| Yes, the Modernist engagement with African art is widely considered to include elements of cultural appropriation. While Modernists often genuinely admired the art, cultural appropriation occurs when elements from one culture are taken and used by members of another, often without understanding, respect, or acknowledgment of the original context, and typically within a power imbalance. Their engagement was largely decontextualized and occurred during intense colonialism, raising significant concerns about power imbalances, failure to acknowledge original cultural significance, lack of attribution, and the one-sided nature of the exchange. My own feelings on it are complicated, but many scholars and I argue appropriation was certainly present, reflecting the colonial mindset. Modern curatorial practice actively aims to address these historical complexities with greater nuance. |

| This is a tricky tightrope, isn't it? Genuine appreciation involves actively engaging with the art and culture with deep respect, seeking to understand its original context, meaning, and purpose, and always giving proper attribution and credit to its creators. Problematic appropriation, on the other hand, often involves extracting elements superficially, stripping them of context, failing to acknowledge the source, and benefiting from another culture's heritage without reciprocity or respect. So, ask yourself: am I learning, honoring, and contributing to a deeper understanding, or simply taking and rebranding? It’s about humility and true, two-way engagement. |

| The collection of African art during the colonial era often involved plunder, forced acquisition, and exploitation, directly linked to colonial expansion and violence. Many objects were removed from their cultural contexts and functions without consent or fair exchange, leading to ongoing debates about restitution and repatriation. Moreover, these objects were often categorized as 'artifacts' rather than 'art,' stripping them of their inherent aesthetic value and reinforcing colonial hierarchies. |

| Modern curatorial practice grapples with several issues: decolonization (critically re-evaluating colonial narratives and practices), advocating for repatriation (returning looted or unethically acquired objects), ensuring ethical provenance (the history of ownership of a work of art), and presenting African art not as ethnographic objects but as significant artistic expressions. This actively involves collaborating with originating communities and living artists to interpret and display their heritage respectfully and with proper attribution, giving voice to the cultures from which the art originates. |

| Many contemporary African artists are actively reclaiming, reinterpreting, and transforming their rich artistic traditions, often engaging in a dialogue with both indigenous aesthetics and global modern and contemporary art movements. They offer vital perspectives that challenge historical misinterpretations, critique the colonial gaze, and contribute to a more inclusive, dynamic understanding of art history, often using their heritage as a source of strength and innovation, rather than simply reacting to Western art. This has led to a vibrant African Modernism, distinct and powerful. |

| The raw materiality of African art – the deep grain of carved wood, the cool smoothness of bronze, the tactile nature of raffia or woven elements – profoundly influenced Modernists. Tired of the illusionistic surfaces of Western art, they were drawn to the directness, authenticity, and physical presence conveyed by these materials. This inspired a more textural, less polished approach in their own work, valuing the visible traces of the artist's hand and the inherent qualities of the medium. |

| In many traditional African societies, women played diverse and crucial roles in art production and use. While men often carved masks and large sculptures, women were frequently responsible for creating intricate textiles, pottery, body adornments, and murals, often imbued with deep symbolic meaning and ritual function. Their artistic contributions were fundamental to communal life, storytelling, and spiritual practice, though often overlooked in Western historical accounts focusing primarily on monumental sculpture. |

| Colonialism played a dual role: it led to the often violent acquisition and looting of African art, but also paradoxically facilitated its widespread dissemination to European museums and private collections. Objects were brought back by explorers, missionaries, and soldiers, often under exploitative conditions, and then displayed in ethnographic museums, making them accessible to European artists. Reproductions in journals and photographs further spread these images far beyond museum walls, but typically without their original cultural context. |

| Look for specific stylistic cues! In Cubism, seek fragmented forms, multiple viewpoints compressed into one plane, and simplified, geometric facial features often reminiscent of masks, often departing from strict anatomical accuracy. For Fauvism, notice bold, non-naturalistic colors, strong outlines, and simplified, rhythmic figures that suggest primal energy. In Expressionism, look for raw, emotionally charged brushstrokes, deliberate distortion, and a palpable sense of spiritual intensity or primal energy, often conveyed through angular forms or symbolic color. Artists like Modigliani show elongated figures and mask-like faces as a clear echo. It’s all about seeking the essence or spirit over literal imitation. |

| To truly appreciate African art's independent evolution, delve into its diverse regional styles, historical periods (e.g., ancient Nok, Ife, Benin kingdoms), and its ongoing contemporary developments. Explore the specific cultural contexts, functions, and philosophical underpinnings of various art forms. Resources from African scholars and institutions are particularly vital here, providing perspectives rooted in their own heritage and moving beyond a Western-centric lens. |

| Beyond this article, look for museum exhibitions that specifically pair African art with Modernist works, and seek out scholarly texts that delve into the history of primitivism and cultural exchange in art. Visiting ethnographic collections alongside modern art museums can offer profound insights, allowing you to draw your own connections and, dare I say, have your own 'jolt' of understanding. I highly recommend 'The Art of Africa' by Peter Garlake or 'African Art in Motion' by Robert Farris Thompson for deeper dives. You might even find parallels in all art styles or explore the broader history of modern art. |