African Art's Profound Influence on Modernism: A Personal Journey

Explore the deep, complex influence of African art on Modernism through a personal lens. Discover its impact on Picasso, Matisse, Expressionism, and abstraction, confronting 'Primitivism' and its colonial roots, and tracing its echoes in contemporary art and my own abstract practice.

Beyond the Canvas: Tracing African Art's Undeniable Influence on Modernism

Sometimes, I find myself staring at one of my abstract paintings, a kaleidoscope of color and form, and a familiar question quietly surfaces: "Where do these ideas truly come from? What threads connect my work to the vast, swirling tapestry of art history?" It’s a bit like trying to trace your artistic family tree. And just as you might uncover a distant ancestor who was, say, a daring explorer or a quiet revolutionary, you occasionally stumble upon influences so profound, so foundational, they make you pause, rethink everything, and maybe even let out a soft "aha!" For many modern artists, that 'aha!' moment, often steeped in problematic colonial encounters, came from an unexpected direction. While European Modernism broadly engaged with various non-Western traditions, from Japanese prints to Oceanic art, the immense, often complicated, influence of African art on the entire trajectory of Modernism is a story that solidified for me personally, and that’s what this journey is about: exploring how these profound historical threads connect, reshape our understanding of art history, and continue to echo in my own creative process.

This isn't just a quaint historical footnote; it's a deep, foundational current, sometimes hidden, sometimes loudly proclaimed, beneath the very edifice of what we now casually label modern art. And trust me, it’s a story worth diving into—a journey of discovery, cultural exchange, and more than a few historical moments that might make you raise an eyebrow (or two, if you’re anything like me), revealing both incredible artistic cross-pollination and the uncomfortable truths of appropriation.

The Urgent Quest for the New: Europe at the Turn of the Century

Picture yourself as an artist in early 20th-century Europe. The world was accelerating at an almost dizzying pace: industrialization, groundbreaking philosophies, the rise of photography challenging painting's traditional role, burgeoning psychological theories exploring the subconscious, and a pervasive sense of disillusionment in the wake of the rigid Victorian era and the impending shadows of global conflict. This was a time of profound existential yearning for renewal, a desire to dismantle the familiar and find new, more authentic ways of seeing and feeling. Tragically, and rather awkwardly, this coincided with the zenith of European colonialism.

As empires aggressively expanded across Africa, countless invaluable artifacts—majestic masks, powerful sculptures, intricately woven textiles—were systematically plundered and brought back to Europe. These objects were often displayed as curiosities in ethnographic museums, rarely, if ever, acknowledged as high art. This context, let’s be absolutely clear, is deeply problematic. The term "Primitivism" itself emerged from this era, a Eurocentric label reflecting a gaze that often fetishized, essentialized, and profoundly misunderstood non-Western cultures. It reduced their millennia-old, complex artistic traditions to something "simple," "instinctual," or merely "exotic." It's a term we must dissect with a critical eye, acknowledging its undeniable historical (and often uncomfortable) role in shaping Western art while condemning its colonial undertones and disregard for the sophisticated functions and meanings of these works. For a deeper look into these difficult conversations, our article on ethical considerations when buying cultural art offers further insights.

A Personal Awakening: The Resonance of Form and Spirit

I remember wandering through a museum once—probably on a quest for coffee, if I’m being completely honest with myself—and stumbling into a room brimming with early 20th-century European art. The jagged lines, the audacious colors, the almost confrontational distorted faces… it all pulsed with a raw, revolutionary energy. It felt so incredibly new. Then, in an adjacent hall, a different kind of power emanated from incredible West African masks and sculptures. Understanding the historical backdrop—this urgent European quest for artistic renewal and the simultaneous, tragic exploitation—made my personal encounter with these art forms even more potent. And that’s when it hit me, with the force of a perfectly aimed conceptual art piece: It wasn't just a fleeting stylistic resemblance; it was an undeniable, profound conversation reverberating across continents, centuries, and distinct cultures.

It’s easy, and perhaps a little comforting, to view Modernism as an entirely European rebellion—a defiant uprising against academic tradition born purely in the cafes and studios of Paris or Berlin. And yes, it absolutely was that: a daring break from realistic representation, an exploration of new modes of seeing, an injection of visceral emotion into art. If you’ve ever had that restless urge to gently (or not so gently) dismantle something perfectly good just to see what happens, just to understand its core, you’ll instinctively understand that rebellious spirit. (And sometimes, in my studio, I still feel that urge to strip away the familiar, to find a new kind of truth in the chaos of creation.) For a deeper dive into this radical shift, you might find our history of modern art article illuminating.

But here’s the unexpected twist, the bit that always makes me smile at history’s delightful ironies: a massive catalyst for this very "newness" stemmed directly from ancient, non-Western traditions—from art forms controversially labeled 'primitive' by the very Europeans who found themselves so utterly captivated. They sought raw passion, directness, and a spiritual profundity that seemed to have vanished from their own artistic traditions.

A Radical New Visual Language: Formal Influences of African Art

Before we delve into the formal innovations, it's crucial to acknowledge the deep spiritual and functional roles these African artworks played in their original contexts. These were not merely decorative objects; they were often imbued with profound meaning, used in rituals, ceremonies, or as conduits to ancestral spirits. The materials themselves – wood, metal, ivory, and textiles – were chosen and worked with immense skill, their textures and patinas often deepening their symbolic power through specific carving techniques, patination, and the application of natural pigments. This inherent vitality, this directness of creation and purpose, was something European artists keenly felt, even if they often divorced the forms from their original meanings. For me, as an artist, the sheer ingenuity of how form and material convey such intense meaning is always a little breathtaking. When I think about the bold, simplified geometric lines in some of my own work, I often wonder if I’m unconsciously tapping into that ancient impulse to distill complex ideas into their most potent visual essence, echoing the deliberate abstraction seen in so much African art.

Through this fraught colonial lens, these African objects resonated with an almost seismic force among European artists. They discovered a potent visual language fundamentally different from their own: a powerful departure from naturalistic representation towards:

- Geometric Abstraction: The bold use of simplified, often angular or curvilinear, shapes to represent forms, moving away from illusionistic detail. Think of the intricate patterns in Kuba textiles or the striking linear designs on Ndebele house paintings.

- Elongated and Distorted Figures: Intentional exaggeration or distortion of features for emotional, symbolic, or spiritual impact, rather than anatomical accuracy.

- Multiple Perspectives / Composite Views: African sculptures were often designed to be viewed from all angles, sometimes incorporating multiple viewpoints simultaneously or showing different facets of a subject at once. This influenced the radical deconstruction of perspective in Cubism.

- Symbolic, Non-Literal Depiction: Art as a vehicle for complex ideas, spiritual communication, or social commentary, where meaning is conveyed through suggestion, abstraction, and established iconography rather than direct mimesis.

- Intense Emotional or Spiritual Charge: These were not mere carvings; they were often 'intercessors', imbued with a life and purpose that seemed utterly absent from the polite salon paintings of their own time.

They were captivated by the way a Fang reliquary figure could convey serene power through its stylized features, or how a Baule mask expressed complex social ideals through simplified forms. This yearning also intersected with new intellectual currents – the rise of psychology and anthropology, which, ironically, while sometimes contributing to colonial narratives, also prompted a questioning of Western rationalism and opened minds to the profound depths of non-Western worldviews. It offered a thrilling, uncharted path forward for their burgeoning modern sensibilities. For more on the broader cross-cultural dialogue, our article on the influence of non-Western art on modernism offers further insights.

Key Modernist Voices: The Transformative Encounters

These artists were prime examples of the seismic shift African art ignited in European sensibilities.

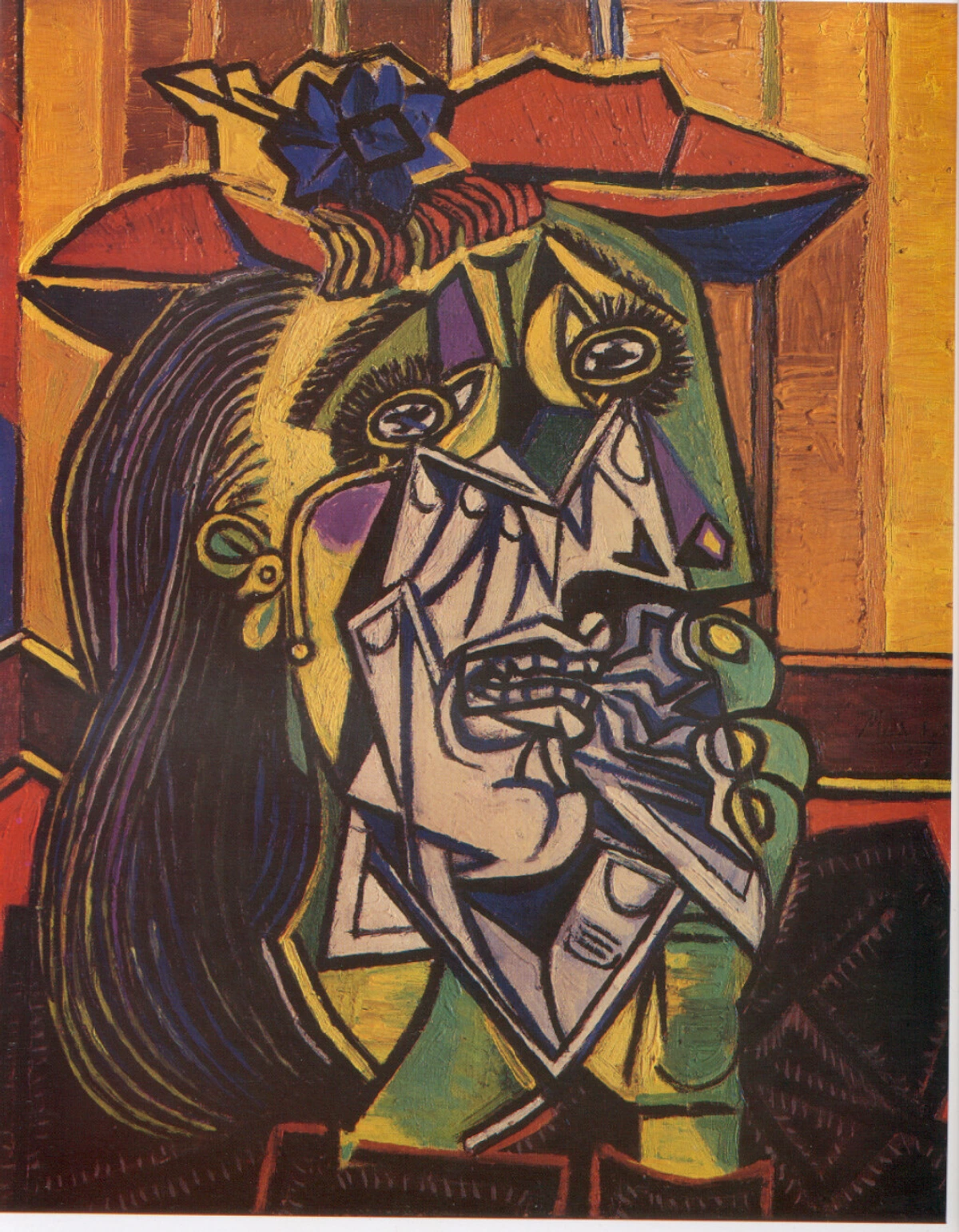

Pablo Picasso: The Catalyst of Cubism

The most iconic tale of this cross-cultural impact undoubtedly centers on the legendary Pablo Picasso. The story, almost mythical now, describes how a somewhat bewildered Picasso visited the Trocadéro Museum in Paris in 1907—a vast repository then filled with 'primitive' art from Africa and Oceania. By his own candid account, he was profoundly shaken, almost haunted, by the African masks and sculptures he encountered there. He famously described them not as mere aesthetic objects, but as "intercessors"—powerful, magical entities capable of mediating between the human and spiritual realms, embodying a raw, protective force.

This encounter, alongside his study of Iberian sculpture, directly ignited the fuse for his revolutionary masterpiece, Les Demoiselles d'Avignon. If you look closely at the faces of the women on the right side of the painting, they are strikingly un-European; instead, they are stark, fragmented, and undeniably mask-like, drawing direct inspiration from both Iberian sculpture and, crucially, the compelling geometry and spiritual intensity of African ceremonial masks. This wasn't merely imitation; it was a profound translation of an aesthetic philosophy, an internalization of the idea that form could convey power and meaning far beyond mere resemblance. The multiple viewpoints characteristic of African sculpture, designed to be viewed from all angles, also informed Cubism's radical simultaneous presentation of different perspectives.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/gandalfsgallery/20970868858, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.0/

This pivotal work, along with Picasso's subsequent radical explorations with Georges Braque, laid the explosive groundwork for Cubism. Cubism shattered traditional perspectives, breaking objects into geometric planes and presenting multiple viewpoints simultaneously. While this deconstruction of form certainly had intellectual roots within European thought, the audacious, geometric simplification and the raw, spiritual power inherent in African sculpture undeniably provided a potent visual vocabulary for this entirely new way of seeing and depicting the world.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/oddsock/101164507, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/

Henri Matisse: The Rhythmic Energy of Fauvism

It wasn’t solely Picasso who felt this magnetic pull. His contemporary, the audacious Henri Matisse, also found profound inspiration, albeit through a distinctly different lens. Matisse, a virtuoso of color and form, emerged as a pivotal figure in Fauvism, an early modernist movement celebrated for its 'wild,' non-naturalistic use of color and boldly simplified shapes. If you’ve ever encountered a painting where trees blaze bright blue or skin glows vibrant green, you’ve likely stumbled upon a Fauvist masterpiece, unapologetically rejecting mimetic representation. For a deeper, more colorful dive into this movement, explore our ultimate guide to Fauvism.

Matisse, a discerning collector, acquired various African sculptures and deeply admired African textiles. What captivated him in these forms was a thrilling liberation from academic constraint: an unbridled emphasis on pure, expressive color, rhythmic line, and an unadorned, direct emotional impact. He wasn't primarily concerned with their ritualistic or ethnographic functions, but rather with their sheer aesthetic power—how they distilled intense feeling and dynamic energy through exquisitely simplified means, much like the vibrant patterns and flat planes of Kuba textiles or the bold, symbolic colors found in many African masks.

https://live.flickr.com/4073/4811188791_e528d37dae_b.jpg, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/

Consider his iconic work, La Danse. The simplified, almost abstract human forms, the robust outlines, the expansive, flat planes of vibrant color—these signature elements, while undeniably Matisse’s unique vision, powerfully echo the bold simplification and energetic rhythm frequently found in many African ritual objects and traditional dances. It’s a pure, unadulterated celebration of form and movement, intentionally stripped of superfluous detail, much like the compelling visual efficiency and spiritual potency of a ceremonial mask or a Yoruba carving.

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/8/87/Henri_matisse%2C_la_danse.jpg, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0

Beyond Parisian Salons: Expressionism's Soul and the Dawn of Abstraction

The reverberations of African art's influence didn't stop at the borders of France; they traveled across Europe, igniting artistic revolutions elsewhere. In Germany, the artists of the Expressionist movements, notably Die Brücke (The Bridge) and Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider), actively sought to articulate profound inner emotion and spiritual truths over mere external reality. Figures like Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Emil Nolde were deeply drawn to the raw, visceral power, directness, and potent symbolic qualities of African, Oceanic, and other non-Western art. Their often angular, intensely distorted figures and vivid, non-naturalistic colors found a powerful resonance with the uninhibited expressive force of African sculpture, such as Fang reliquary figures or Baule masks, which prioritize spiritual evocation over anatomical accuracy. This embrace of essential forms also extended to sculptors like Constantin Brâncuși. His focus on the essential form, the truth to materials, and the direct carving methods—stripping away superfluous detail to reveal the inherent spiritual presence—resonated deeply with the artistic philosophies embodied in many African and Oceanic sculptures, such as the elegant forms of Luba caryatids or Dogon ancestor figures. For more on this emotionally charged era, explore our ultimate guide to Expressionism.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/vintage_illustration/51913390730, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/

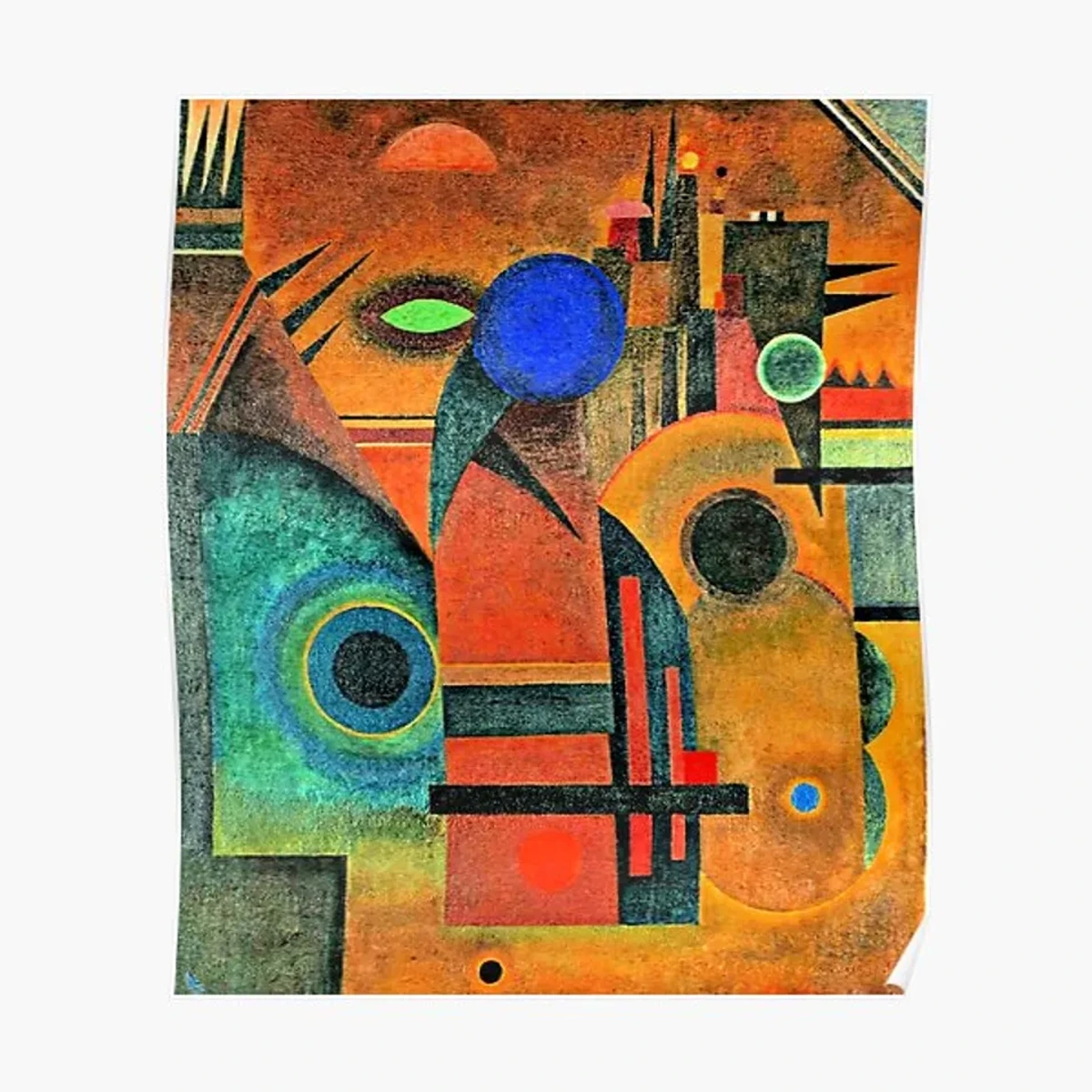

This widespread turning towards simplification, profound symbolic meaning, and heightened emotional intensity ultimately laid the fertile groundwork for the radical development of abstract art. Artists like Wassily Kandinsky, often considered a pioneer of pure abstraction, while perhaps not directly 'borrowing' from African forms in the same explicit way as Picasso, were undoubtedly part of this broader intellectual and spiritual movement. He sought for art to speak a universal language, much like music, directly to the soul, bypassing literal representation entirely. The symbolic, non-literal, and emotionally charged forms of African art, with their intrinsic power to convey deep meaning without mimesis (the imitation of the real world), undeniably contributed significantly to the intellectual climate that allowed pure abstraction to not just flourish, but explode onto the global stage. Exploring the history of abstract art truly illuminates this profound progression.

Printerval.com, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

More Than Mere Inspiration: Appropriation and Paradigm Shift

So, we’ve traced the threads of influence across Europe, but now comes the moment for a deeper look into the mirror, at the inherent complexities and uncomfortable truths. The relationship between European modernists and African art was, regrettably, not always a respectful, reciprocal dialogue. More often, it was an act of appropriation—forms were detached from their rich cultural and ritualistic contexts, stripped of their original, profound meanings, and then reinterpreted through a distinctly Western, often colonial, gaze. It’s akin to taking a sacred object, stripping it of its spiritual context and name, and then reinterpreting it purely for its aesthetic qualities in your own artistic narrative. This act, while sparking undeniable innovation, too often reinforced problematic power dynamics, turning profound cultural expressions into mere artistic raw material. Awkward, right? And a situation that still resonates today, sparking vital discussions around cultural ownership, restitution, and the ethics of museum collections.

However, despite these ethical complexities, we simply cannot deny the profound, transformative artistic impact. African art didn't merely offer new ideas; it fundamentally reshaped the Western artistic paradigm. It provided European modernists with:

- A Radical New Visual Language: A bold leap beyond the confines of realistic representation towards groundbreaking geometric forms, pure abstraction, and powerful stylization.

- A Renewed Emphasis on Spiritual and Emotional Content: Art was reimagined as a potent vehicle for deeper meaning, visceral emotion, and spiritual connection, transcending mere surface beauty or narrative illustration.

- A License to Break All Rules: A profound liberation from centuries of academic norms, granting artists permission to dismantle conventions. This included challenging the strictures of anatomical accuracy, linear perspective, and the sole focus on narrative or mythological subjects, opening the door for courageous exploration of radical new expressions.

This wasn't merely about copying intriguing shapes; it was about internalizing and translating an entirely different philosophy of art-making—one that championed symbolic power, raw emotional resonance, and a deeper engagement with the unseen, over literal depiction. It was a true paradigm shift.

African Art's Enduring Modernity: A Two-Way Street

While European Modernism undeniably looked to African traditions for renewal, it’s equally vital to recognize that African art was never static, nor were African artists merely passive recipients of Western influences. African art encompasses incredibly diverse and sophisticated traditions spanning thousands of years, long predating Western Modernism. Many African art forms are inherently abstract, highly stylized, and conceptually rich, exhibiting characteristics that later became hallmarks of modern art, such as abstraction, symbolism, and a focus on essential form, demonstrating its timeless innovation and profound sophistication.

As the 20th century progressed, a vibrant African Modernism emerged, often blending indigenous artistic practices with new forms, materials, and ideas introduced through global exchange. Artists like Ben Enwonwu in Nigeria, whose iconic sculpture "Anyanwu" (1954-55) powerfully merges traditional Igbo aesthetics with modernist stylization, or the sculptors of the Cyrene School in Libya, engaged with their own rich histories and identities while also critically responding to Western influences. This period saw a powerful assertion of unique African voices in the global art scene, proving that the conversation was, and continues to be, a rich, multifaceted dialogue, not a one-way street. These artists weren't just influenced; they were also influencing, redefining what "modern" meant from their own perspectives, often reclaiming and reinterpreting traditional forms in contemporary ways. This re-evaluation was further amplified by post-colonial thought, which critically examined the historical power imbalances and advocated for the repatriation of cultural artifacts and the rightful recognition of African agency in shaping global art history. For me, it's a continuous, evolving dialogue, prompting us to ask: how do we responsibly acknowledge historical influences while honoring original contexts and creators? To explore more about these dynamic artists, consider our spotlight on contemporary African diaspora artists.

Echoes in My Studio: A Personal Synthesis

As an artist crafting abstract art prints and paintings for sale, this intricate history resonates with me on a deeply personal level. While I’m certainly not consciously "borrowing" from specific African forms—nor would I ever claim a cultural connection I don't possess—the enduring spirit of that modernist break, that audacious quest for raw expression and simplified, emotional power, is something I constantly strive for in my own compositions. I see it in the bold, geometric interplay of shapes, and the vibrant, non-representational use of color in my work, much like the compelling efficiency found in a ceremonial mask or the directness of a stylized figure.

It's a powerful reminder that true innovation often springs from daring to look beyond the familiar, from challenging those ingrained assumptions about what art "should" or "must" be. My own artistic journey, much like the wider, ever-unfolding story of art, is one of continuous learning, rigorous experimentation, and passionate evolution. If you’re curious to trace the threads of my personal artistic path, you can always explore my artist's timeline. I truly believe that understanding these rich, complex historical influences helps us not only better appreciate the art of yesterday but also find deeper meaning in the art of today, including, I hope, my own work. Perhaps this understanding also helps explain that restless urge to 'dismantle' I mentioned earlier – it's about getting to the core, the essence, much like the artists of Modernism sought to do. The lasting legacy of these cross-cultural encounters continues to inform contemporary art practices, reminding us that artistic evolution is always a global conversation.

FAQ: Unpacking African Art's Influence on Modernism

Q: What exactly is "Primitivism" in art?

A: Primitivism refers to a significant trend in early 20th-century Western art where European artists drew inspiration from what they often perceived, through a colonial lens, as 'primitive' or 'less developed' cultures—primarily those of Africa, Oceania, and indigenous Americas. While it undeniably introduced new forms and expressions into Western art, the term itself is highly problematic and Eurocentric, reflecting a mindset that frequently romanticized, essentialized, and profoundly misunderstood the rich, complex, and ancient artistic traditions of non-Western societies. It is critiqued today for its colonial origins and its reduction of diverse cultural practices to a singular, often demeaning, label.

Q: Which modern artists were most influenced by African art?

A: The most iconic and foundational figures include Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse, who were instrumental in the development of Cubism and Fauvism respectively. However, the influence extended far wider, profoundly impacting artists across various movements, particularly German Expressionists like Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Emil Nolde (from groups like Die Brücke), as well as sculptors such as Constantin Brâncuși.

Q: Was it just copying, or was there deeper engagement?

A: It was far more complex than mere copying. While aspects can certainly be viewed as direct appropriation, many modernists were profoundly inspired by the underlying principles of African art: its bold simplification of form, its powerful spiritual intensity, its radical rejection of Western naturalism, and its ability to convey potent emotion and profound meaning through abstraction and stylization. They integrated these philosophical and aesthetic insights into their own distinct Western artistic languages, leading to truly innovative outcomes.

Q: How did African art influence specific techniques in Modernism?

A: African art inspired several technical shifts:

- Geometric Simplification: Modernists adopted the use of stark, angular, and curvilinear forms to deconstruct and represent subjects, moving away from illusionistic detail.

- Shift in Perspective: The composite views and fragmented forms in African sculpture, designed for ritual observation from multiple angles, influenced Cubism’s multi-perspective approach.

- Expressive Distortion: The intentional exaggeration or distortion of features for emotional or symbolic impact, seen in many masks and figures, found parallels in Expressionist portraiture.

- Bold, Non-Naturalistic Color: While Matisse's color use was his own, the freedom from literal color in African textiles and painted objects reinforced the idea of color serving emotional or symbolic, rather than descriptive, purposes.

- Negative Space and Voids: The deliberate use of negative space and 'voids' as integral compositional elements in some African sculptures also offered a novel approach to form, influencing modernists to consider the interplay of solid and empty space as equally significant.

Q: What are the ethical concerns surrounding the use of African art by European Modernists?

A: The primary ethical concern lies in the context of appropriation and colonialism. European modernists often encountered African art through exploitative colonial channels, detaching objects from their original spiritual and cultural meanings. They reinterpreted these forms through a Western lens, often without acknowledging the original creators or cultures, and sometimes perpetuating a problematic "primitive" label. This act of appropriation reinforced power imbalances and overlooked the sophisticated artistic traditions from which these forms originated. It raises crucial questions about ownership, credit, and the respectful engagement with cultural heritage that continue to be debated today, including calls for the repatriation of cultural artifacts.

A Journey of Continuous Discovery

The narrative of African art’s indelible influence on Modernism is a vibrant, complex tapestry—one that continues to unravel and reveal new insights. It serves as a potent reminder that art is an ongoing, boundless conversation, constantly evolving, perpetually borrowing, and often, beautifully sparking passionate debate. It stands as a powerful testament to the universal, boundless power of human creativity, and the endlessly fascinating, often unexpected ways cultures intersect, challenge, and profoundly inspire one another.

This ongoing dialogue certainly keeps me thinking, questioning, and creating—and perhaps, that’s the most profound influence of all. What connections have you discovered that reshaped your view of art? If you ever find yourself in 's-Hertogenbosch, I would be genuinely delighted for you to drop by my museum and experience some of my work firsthand, perhaps even to continue this intricate conversation about art and its endless influences. Because, truly, the story never ends.