Indigenous Art's Enduring Influence on Modern Abstraction: A Curator's Reflection

As a curator and artist, I delve into Indigenous art's profound influence on modern abstraction, from Cubism to contemporary works, exploring its conceptual depth, the 'Primitivism' paradox, and the vital call for responsible, introspective engagement today. It's a dialogue still echoing.

Beyond 'Primitivism': Indigenous Art's Enduring, Introspective Influence on Modern Abstraction

As a curator and an artist, I confess I'm always on the hunt for the hidden connections that truly animate art history. I love uncovering the whispered conversations across centuries and cultures that subtly, yet profoundly, shape our understanding of art. This journey often leads me to reflect on narratives that, at first glance, might seem peripheral to the grand story of Western modernism, but upon closer inspection, reveal themselves as foundational. One such immensely impactful, yet often simplified or even overlooked, dialogue is the enduring influence of Indigenous art on modern abstract movements. It's a journey into the history of abstract art that’s far more intertwined than many realize, a secret handshake across time and space that's still echoing today. Sometimes I wonder if the real 'discovery' was realizing we were all speaking variations of the same visual language all along – just in different accents, perhaps.

For too long, the dominant narrative of modern art has been painted with broad European strokes, a story of singular innovation emerging from bustling Parisian ateliers. Yet, if we lean in closer, if we truly listen, a richer, more complex tapestry unfolds – one woven with continuous, vibrant exchanges between Western artists and the profound artistic traditions of Indigenous cultures worldwide. It’s a dialogue that didn't just add a splash of "exotic" flavor; it fundamentally reshaped how artists perceived form, color, and meaning, propelling them towards abstraction and challenging the very definitions of what art could be.

The "Primitivism" Paradox: A Complicated Catalyst

By the turn of the 20th century, European art felt like a gilded cage. There was a restless, yearning energy for new forms of expression, a palpable hunger for something raw, authentic, and direct, a stark contrast to the perceived decadence and over-intellectualization of academic art. It was in this fertile, slightly desperate ground that many European artists "discovered" the powerful, unbridled aesthetics of African, Oceanic, and Indigenous American art. This fascination, often branded "Primitivism," was, undeniably, a deeply complicated affair. It was transformative for the artists themselves, offering a radical departure from convention, yet it was also undeniably laden with colonial undertones, reducing complex living cultures to static, anonymous sources of "raw" aesthetic material. It's a part of art history that still makes me squirm a little, honestly, given the inherent power dynamics. I often think about the irony: searching for authenticity, yet often stripping it away in the process. It's a human failing, I suppose, to see only what we want to see.

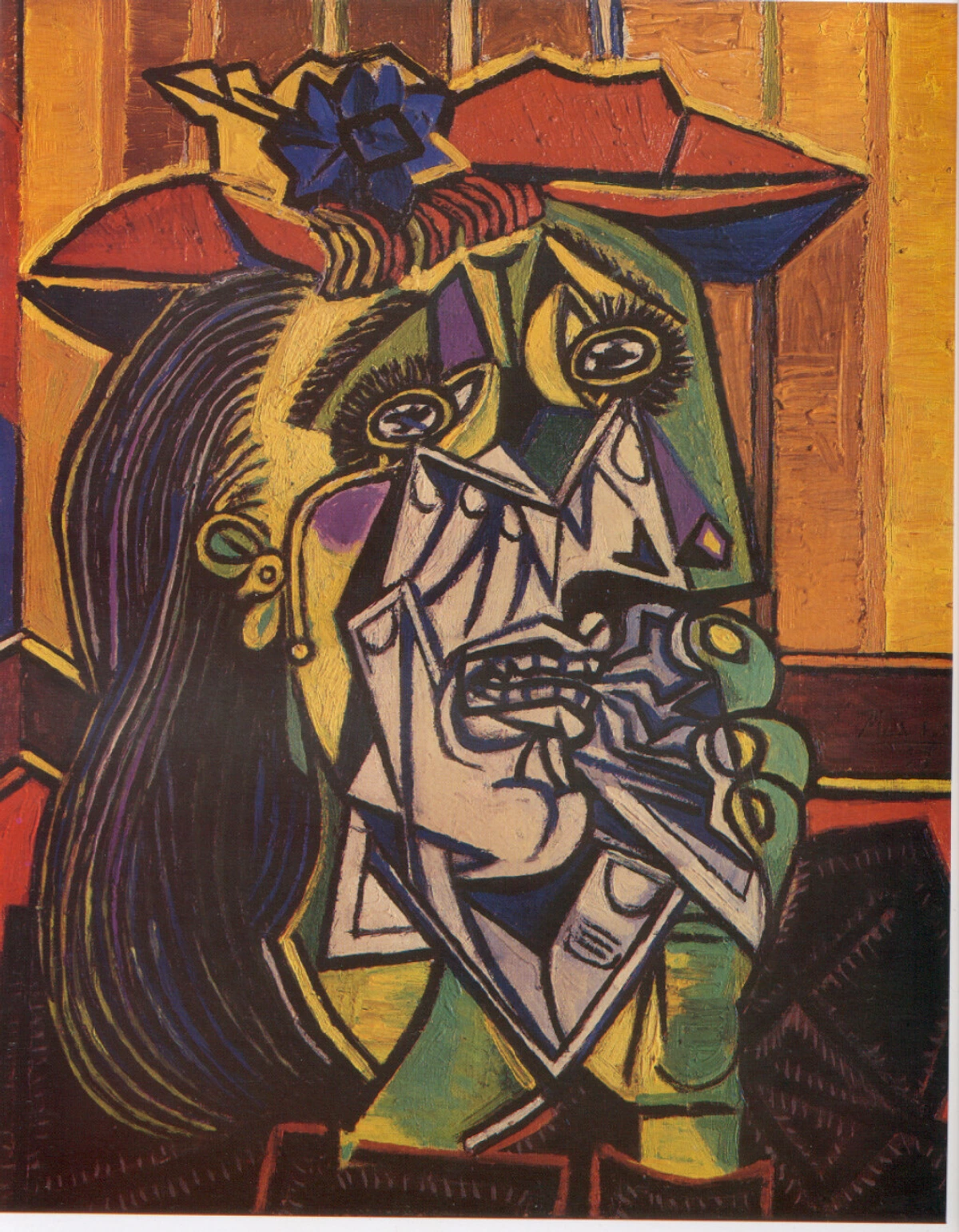

Artists like Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse were captivated by the raw energy, simplified forms, and expressive power embedded in masks and sculptures from Africa (such as those of the Dan or Fang peoples) and Oceania (like Malanggan carvings from New Ireland). Picasso's groundbreaking work, particularly his development of Cubism, famously drew inspiration from these forms. He didn't just copy them; he used their radical reordering of perspective and their symbolic directness to fracture his own understanding of reality, reassembling it in ways that shocked and revolutionized the art world. It was a paradigm shift, seeing art not as a mirror to reality but as a profound means to express deeper truths and internal states, echoing the spiritual and functional roles of the art that inspired him. You can almost hear the gears turning in his head, can't you? A seismic internal shift, mirrored on canvas.

Matisse, too, found a liberation in the bold lines and flattened perspectives, moving towards the vibrant, expressive qualities that defined Fauvism. His early works, often with their flattened forms and vibrant palettes, demonstrated this fresh perspective, a kind of joyous visual rebellion.

His later cut-outs, like 'La Gerbe,' demonstrate a continued pursuit of simplified, abstract forms and vivid color, mirroring the directness seen in many Indigenous textile designs or bark paintings. While the term "Primitivism" is now widely critiqued – and rightly so – for its decontextualization, exoticization, and erasure of non-Western cultures, its undeniable role as a catalyst for breaking free from academic constraints is irrefutable. It was a moment of profound, albeit imperfect, cross-cultural pollination. For a more detailed exploration of this specific cross-cultural exchange, you might find my earlier piece, Understanding the Influence of African Art on Modernism, particularly insightful.

The Unseen Foundations: Echoes of Deep Time

Before we even talk about modernism, it’s crucial to acknowledge that the seeds of abstraction were thriving in diverse human cultures long before Western artists 'stumbled upon' them. Indigenous art, spanning millennia and continents, often embraced abstraction, symbolism, and non-representational forms not as an aesthetic choice for its own sake, but as an inherent part of spiritual, ceremonial, or narrative purposes. These weren't mere decorations; they were maps, histories, and spiritual conduits, embodying entire visual languages. Perhaps we're all just a little late to the party, endlessly fascinated by the conversations that have been happening for millennia.

Think of the ancient rock art of the Australian Aboriginal peoples, dating back tens of thousands of years, or the sophisticated geometric patterns in pre-Columbian textiles from the Andes. These forms speak to an inherent human capacity for abstraction, long predating European 'modern' innovations. I sometimes wonder if this innate human drive to abstract is just part of our DNA – a way to grasp the complex by simplifying it.

Yet, this story of "discovery" is, I find, deeply uncomfortable. It’s hard to ignore the power imbalance inherent in the way these traditions were often appropriated. For too long, the 'why' behind these powerful Indigenous forms – their deep spiritual, ceremonial, or communal purposes – was stripped away, leaving only the aesthetic shell for European consumption. The dominant narrative of modernism actively excluded or ignored the contributions and perspectives of Indigenous artists themselves, effectively erasing their agency in the "discovery" process. This decontextualization is precisely why re-examining these influences is so vital today. It’s not just about correcting historical oversights; it’s about reclaiming voices, challenging colonial narratives, and acknowledging the profound, pre-existing sophistication of Indigenous artistic philosophies.

Beyond Aesthetics: Shared Conceptual Ground

The impact of Indigenous art wasn't just aesthetic; it was profoundly conceptual. What struck these modern artists, I believe, was not just the "look" but the underlying philosophy. Indigenous art, often created for spiritual, ceremonial, or narrative purposes, inherently embraced abstraction, symbolism, and non-representational forms long before Western modernism coined these terms. This offered a compelling, ancient alternative to the Western tradition's centuries-long emphasis on naturalism and illusionism – the idea that art should primarily mimic reality. It's almost as if they were speaking the same language, just in different accents, revealing a universal human impulse to express the ineffable, the things words simply can't capture.

Modern abstract artists, in their quest to break free from convention and find new ways to express the intangible, found deep resonance in these ancient approaches. They began to explore with renewed vigor:

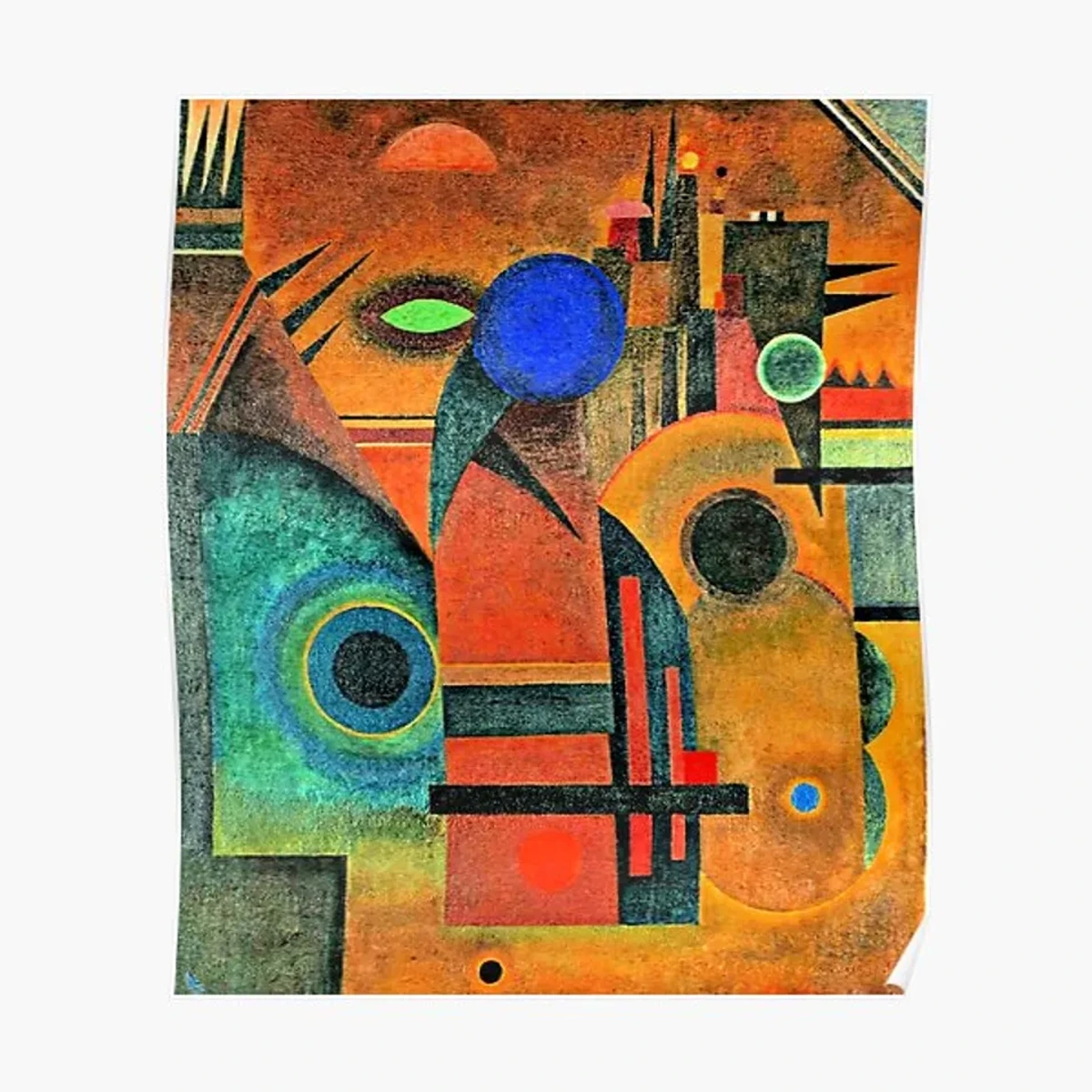

- Symbolism and Narrative as Visual Language: Indigenous art is rich with intricate symbols that convey complex stories, beliefs, and cosmological views – essentially, entire visual languages. Think of the potent, story-rich designs in Plains Nations beadwork, the narrative complexity of Northwest Coast Indigenous masks, or the intricate bark paintings of Australian Aboriginal cultures. These forms are not just beautiful; they mean something deeper, much as Indigenous art has always done. Modern artists, like Wassily Kandinsky, sought a similar spiritual or emotional depth in their abstract compositions, moving beyond literal depiction to evoke feeling, idea, and a sense of the universal. His search for an inner, spiritual resonance in art feels directly connected to the profound symbolic systems of Indigenous cultures, a quest for a visual grammar of the soul.

- Geometric Abstraction and Cosmic Order: From the intricate, sacred patterns of Navajo weaving and sand paintings to the bold lines and symbolic representations of Australian Aboriginal dot paintings, and even the precise designs of pre-Columbian textiles from the Andes, Indigenous cultures have masterfully employed geometric shapes and repetitive patterns to create visually stunning and deeply meaningful works. These often reflect a cosmic order or spiritual geometry. Western artists like Piet Mondrian and Kazimir Malevich, though operating within vastly different cultural contexts, shared this profound interest in universal geometric order and its capacity for essential expression. Mondrian himself reportedly studied Native American art, searching for elemental forms that transcended specific cultures, a testament to the cross-cultural appeal of foundational shapes. He was looking for the visual 'bones' of reality, much like these ancient traditions.

- Materiality, Texture, and Primal Expression: Indigenous artists often utilize natural pigments, fibers, and found objects, celebrating the inherent qualities of their materials, their raw tactility, and their connection to the earth. This emphasis on texture and raw materiality resonated deeply with subsequent Abstract Expressionists. Think of Jackson Pollock's drips, Willem de Kooning's agitated brushstrokes, or Antoni Tàpies' use of rough, found elements. They favored thick impasto, visible brushstrokes, and non-traditional media to convey primal emotion, immediate presence, and a sense of unmediated artistic action, much like the directness often seen in Indigenous art. It's almost as if they were channeling a primal scream onto the canvas, rendered in paint and earth, seeking a fundamental connection to the physical world. I know in my own practice, the feel of the paint, the way it interacts with the canvas, is as much a part of the 'story' as the image itself.

- Process, Ritual, and Holistic Art-making: What if the act of creation itself was as significant as the final product? Beyond the aesthetic qualities, the very approach to art-making in many Indigenous cultures – where art is often inseparable from ritual, community, and daily life – offered a profound conceptual challenge to Western notions of art as a commodity or purely aesthetic object. This holistic view, where the process of creation holds deep meaning, seeped into modernist thought, influencing artists' exploration of performance, process art, and the spiritual dimensions of their work. From the meditative act of a sand painting, destroyed after its ceremonial use, to the improvisational intensity of action painting, the echoes are undeniable. They saw art as something lived, breathed, and integrated, not just displayed – an idea that deeply resonates with my own creative philosophy. I find myself returning to this idea constantly in my studio.

Here’s a snapshot of how these principles align:

Indigenous Art Characteristic | Description | Western Modernist Parallel | Specific Artists/Movements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Symbolism & Narrative (Visual Language) | Complex stories, beliefs, cosmology conveyed through visual systems | Spiritual/emotional depth, universal language | Kandinsky, Symbolism, Expressionism, Cobra |

| Geometric Abstraction (Cosmic Order) | Sacred patterns, bold lines, repetitive designs reflecting order | Universal geometric order | Mondrian, Malevich, Constructivism, Op Art |

| Materiality & Texture (Primal Expression) | Celebration of natural pigments, fibers, raw tactility | Primal emotion, direct presence, connection to earth | Abstract Expressionism, Art Informel, Arte Povera |

| Process & Ritual (Holistic Art-making) | Art inseparable from community, ceremony, life; emphasis on creation act | Performance, process, spiritual art | Action Painting, Performance Art, Conceptual Art |

An Ever-Unfolding Conversation: From Modernism to Today

The dialogue between Indigenous art and modern abstraction is not a dusty chapter confined to the early 20th century; it's an ever-unfolding conversation that continues to resonate powerfully. This influence extends beyond the initial formal appropriations, touching on deeper conceptual and spiritual explorations.

Consider Barnett Newman, an American Abstract Expressionist, who famously studied Native American art – particularly the potent, simplified forms and spiritual resonance found in totem poles and ceremonial objects. He sought to create a "sublime" art that transcended mere representation, much as Indigenous art often does, connecting with universal, elemental truths through his stark, monumental "zip" paintings. His fascination wasn't with surface aesthetics, but with the profound sense of scale and spiritual void these objects evoked, aiming for a similar unmediated, awe-inspiring presence in his own work. It's a fascinating leap from specific cultural forms to a universal spiritual language.

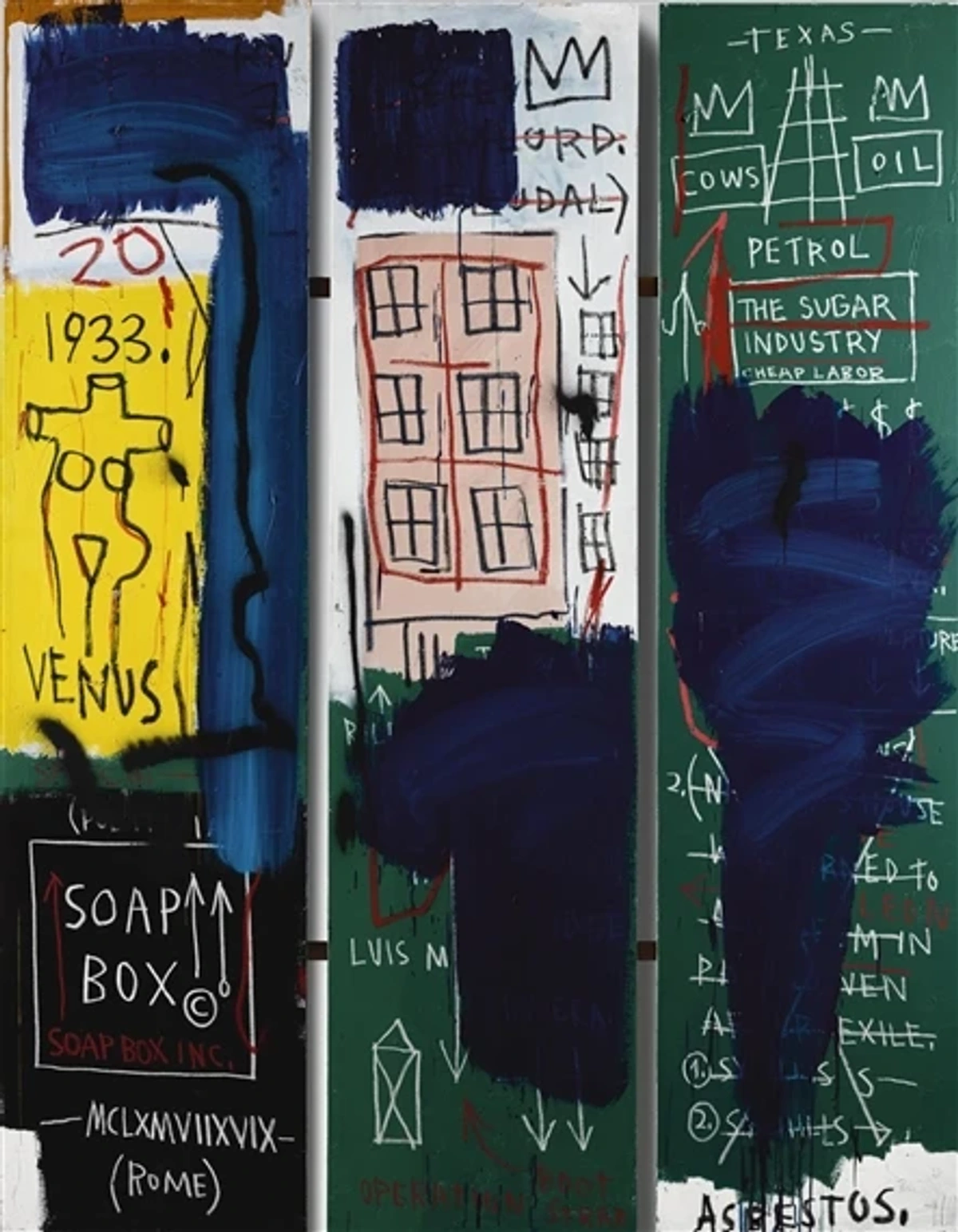

When I look at the raw, gestural energy and symbolic intensity in the work of Jean-Michel Basquiat, I can't help but see echoes. While his immediate influences were a vibrant mix of graffiti, street art, jazz, and comics, the visceral power, layered narratives, and symbolic motifs in his paintings often evoke a connection to the expressive force seen in various Indigenous art forms. His work, a complex amalgamation of text, figures, and abstract marks, speaks to a direct, unmediated form of communication, a potent visual language that bypasses traditional academic constraints, much like the visual languages of many Indigenous cultures. It prompts us to consider how art, regardless of its origin, can tap into universal human experiences, archetypes, and a primal need to communicate. It's like he bottled raw energy and then uncorked it on canvas, a kind of modern-day cave painting.

My Art, This History: An Artist's Reflection

For me, as an artist creating contemporary abstract pieces, I'm profoundly aware of this rich lineage. While my canvases are not direct interpretations of specific Indigenous forms, the understanding of how early modernists broke free from conventions – partly inspired by the conceptual and formal innovations of Indigenous forms – deeply informs my own pursuit of expressive, non-representational art. It's a reminder that truly compelling art often draws from a wellspring of diverse human creativity across time and cultures. It's about finding that universal resonance. I often feel like I'm standing on the shoulders of giants, even those whose names aren't always explicitly on the Western art history syllabus.

My studio practice, with its emphasis on intuitive mark-making and the exploration of color as a language, often mirrors the directness and emotional potency I admire in Indigenous art. For instance, when I’m layering colors, letting them bleed and interact, I’m consciously engaging with the idea of 'story' through pure visual means, much like a complex weaving or a bark painting conveys narrative without explicit figures. It's less about literal representation and more about conveying an inner world, a feeling, a conversation between color and form that speaks on a deeper level. This historical understanding gives me a compass, reminding me that the pursuit of the 'new' often finds its deepest roots in the ancient, in art forms that have always prioritized meaning over mere mimesis. You can explore my journey and approach in my abstract art styles or see my current art for sale sections. My artistic timeline also reflects this continuous learning and connection to a broader human artistic heritage.

Reclaiming Agency: Contemporary Indigenous Art's Powerful Trajectory

It’s vital to remember that the influence isn't a one-way street confined to history. Contemporary Indigenous artists are not simply preserving traditions; they are dynamically extending them, engaging with global art dialogues, and continuing to innovate within and beyond abstract forms. Artists today – from the global Indigenous art scene – are challenging static notions of "tradition," using abstraction, narrative, and materiality to explore identity, history, and contemporary experiences with profound agency. For instance, the late Emily Kame Kngwarreye, an Anmatyerr woman from Australia, created monumental abstract paintings that resonate with the ancient stories of her country, transforming traditional ceremonial body paint designs into globally recognized abstract masterpieces.

Similarly, artists like Kent Monkman (Cree, Canada) use painting and performance to critically engage with colonial narratives while reasserting Indigenous presence and sovereignty, often employing stylized, abstracted forms. Beyond these, artists like Kay WalkingStick (Cherokee, USA) blend abstract landscapes with Native American motifs, creating a dialogue between place, memory, and abstraction. These artists, and countless others, are not only reinterpreting their ancestral aesthetics but also actively critiquing and re-contextualizing the historical Western gaze on their work, forging a truly multi-directional and vital global art conversation. Their work serves as a living testament to the enduring vitality and dynamism of Indigenous cultures and their artistic practices, powerfully shaping the future of art, including the ongoing evolution of abstract expression. It's a powerful statement that their art, like all great art, is alive and constantly evolving.

![]()

More Than Admiration: Towards a Responsible Engagement

Recognizing this profound influence of non-Western art on modernism comes with a deep and often complex responsibility. As curators, collectors, and enthusiasts (myself included, certainly), it's crucial to move beyond simplistic notions of "borrowing" or "inspiration" and engage with Indigenous art respectfully, acknowledging its original contexts, spiritual significance, and the sovereignty of its creators. It’s not enough to admire; we must understand and respect.

We must strive to:

- Support Indigenous Artists Directly: Directly acquiring works from contemporary Indigenous artists ensures fair compensation and recognition of their ongoing contributions. It’s about direct action, not just academic appreciation – put your money where your reverence is. It's a small but significant act of decolonization in your own collection.

- Understand Context Deeply: My own studies have taught me that learning about the specific cultures, histories, and meanings embedded within Indigenous artworks is paramount. We must avoid generalizing, exoticizing, or stripping these powerful works of their original intent. Always ask: what is the story behind this object, and who is telling it? And if no one is telling it, perhaps you’re not looking closely enough.

- Promote Education and Dialogue: Advocating for exhibitions and scholarly work that highlight Indigenous art's global significance and its rightful, sovereign place in the broader narrative of art history is essential. Museums, like the one I proudly oversee in 's-Hertogenbosch, play a vital role in this education, fostering genuine cross-cultural dialogue and supporting initiatives like repatriation and collaborative curation.

- Acknowledge Attribution and Agency: Always attribute Indigenous artworks and cultural forms to their specific creators, communities, and nations. Avoid the historical erasure of individual and collective agency that characterized much of the "Primitivism" era. These are not anonymous objects; they are expressions of specific people and traditions.

The journey through the history of abstract art is indeed a complex and endlessly fascinating one, revealing layers of cross-cultural fertilization and profound human connection. By genuinely engaging with the enduring influence of Indigenous art, we not only enrich our understanding of modernism but also foster a more inclusive, respectful, and truthful appreciation of global artistic heritage. It's a journey that deeply resonates with my own artistic timeline and continuous learning, reminding me that art, at its core, is a universal language spoken in myriad, beautiful ways. It’s a conversation worth leaning into, with open ears and an open mind.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is "Primitivism" in art, and why is it problematic?

"Primitivism" refers to a Western art movement of the late 19th and early 20th centuries where artists drew inspiration from the art of non-Western, pre-industrial, and Indigenous cultures, often perceived as "primitive" or less developed. While it was a catalyst for radical artistic innovation in the West, helping break free from academic traditions, the term and practice are now widely critiqued for their colonial implications and inherent power dynamics. It often involved decontextualizing and exoticizing the source material, appreciating its aesthetics without fully understanding or respecting its original cultural significance, spiritual purpose, or the sovereignty and agency of its creators. It's a bit like admiring a beautiful shell without understanding the living creature that once inhabited it, reducing a complex ecosystem to a mere curio – pretty, but tragically incomplete.

Which modern artists were significantly influenced by Indigenous art, beyond the early Cubists?

While Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse are perhaps the most famous for their early engagement with African and Oceanic masks and sculptures (informing Cubism and Fauvism), the influence extended much further. Constantin Brâncuși and Amedeo Modigliani also drew inspiration from simplified, totemic forms. Later, Abstract Expressionists like Barnett Newman famously studied Native American art, seeking spiritual and sublime qualities for his monumental "zip" paintings. Jean-Michel Basquiat's work, though rooted in street culture, resonates strongly with the raw, symbolic, and narrative energies seen in various Indigenous art forms. The conversation continues with many contemporary artists globally, often more consciously and respectfully, such as Emily Kame Kngwarreye (Australia), Kent Monkman (Canada), and Kay WalkingStick (USA).

How can one appreciate Indigenous art responsibly in the modern era?

Responsible appreciation of Indigenous art involves several key aspects:

- Educate Yourself Thoroughly: Seek to understand the specific cultural context, history, and meaning behind the artwork, moving beyond a purely aesthetic gaze. This isn't just looking; it's learning, and avoiding broad generalizations that flatten diverse cultures.

- Acknowledge Sovereignty and Rights: Respect the rights of Indigenous peoples over their cultural heritage and intellectual property, including advocating for repatriation of cultural objects. This is about recognizing a profound ethical dimension.

- Support Indigenous Artists Directly: Whenever possible, purchase art from Indigenous creators and their communities, ensuring economic benefit directly supports them and their cultural continuity. Voting with your wallet, as they say, makes a real difference.

- Avoid Appropriation: Clearly differentiate between respectful inspiration (which involves deep study, attribution, and understanding) and cultural appropriation (taking elements out of context without understanding, permission, or benefit to the original creators). It's a fine line sometimes, but crucial to navigate with integrity.

- Engage with Cultural Institutions: Visit museums and cultural centers that present Indigenous art thoughtfully and ethically, often in consultation with Indigenous communities, and advocate for such practices. Support institutions actively working towards decolonizing their collections and narratives.

- Demand Proper Attribution: Always ensure Indigenous artworks are attributed to their specific creators, communities, and nations, recognizing their individual and collective artistic agency. They deserve that recognition, just like any Western master.