Georges Seurat: Pointillism, Neo-Impressionism & The Science of Seeing – A Curator's Definitive Guide

Discover the profound genius of Georges Seurat: his meticulous Pointillism, Neo-Impressionism, and the scientific theories that revolutionized art. Explore 'La Grande Jatte' and his enduring, meticulous legacy in this authoritative guide.

Georges Seurat: Pointillism, Neo-Impressionism & The Science of Seeing – A Curator's Definitive Guide

When I first encountered Georges Seurat's work, it wasn't just the sheer optical vibrancy that captivated me; it was the profound sense of intellectual rigor, the quiet, almost meditative authority emanating from the canvas. Seurat (1859-1891) was more than an artist; he was a meticulous scientist, a quiet revolutionary who, in his tragically brief life, dared to redefine the very act of seeing. Far from the spontaneous gestures of his Impressionist contemporaries, Seurat approached art with the precision of a laboratory experiment, transforming light and color into a new, intellectually charged language. His monumental works, particularly his magnum opus, "A Sunday on La Grande Jatte," compel us not merely to observe, but to actively participate in the optical alchemy unfolding before our eyes. It’s an experience that, for me, truly challenges conventional perceptions of art and indeed, perception itself, inviting us to slow down and truly see. This is the definitive guide for anyone seeking to truly understand Seurat, the meticulous visionary who laid the groundwork for so much of modern art.

In this article, we'll delve into the structured world Seurat built: from his academic foundations and the scientific theories that inspired him, to the masterpieces he meticulously crafted, the profound theoretical framework he constructed, and the lasting legacy he left on the trajectory of modern art. Prepare to explore how a quiet mind orchestrated a visual revolution, turning the canvas into a finely tuned instrument of light and emotion.

![]()

The Young Visionary: Academic Roots and a Scientific Spark

Born Georges-Pierre Seurat in Paris in 1859, he was, by all accounts, a reserved and deeply methodical individual. I often ponder what thoughts occupied such a focused mind, seemingly untouched by the fleeting whims that captivated so many of his peers. His father, Antoine-Chrysostome Seurat, a retired legal official, instilled a sense of order and quiet discipline that perhaps resonated with the young artist's temperament. His artistic journey began with formal training at the École des Beaux-Arts from 1878 to 1879, where he studied under Henri Lehmann, a pupil of the Neoclassical master Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. This classical education wasn't just about technique; it instilled in Seurat a profound appreciation for line, form, and composition – a structured approach that would profoundly inform his later innovations. During these formative years, he would have meticulously studied Old Masters, focusing intensely on drawing, anatomy, and the precise rendering of form, developing a robust foundation that underpinned his revolutionary break from tradition.

While absorbing academic traditions, Seurat also keenly observed the emerging Impressionist movement, admiring their pursuit of capturing light and color in fleeting moments. Yet, and this is where his unique vision truly began to coalesce, he perceived a fundamental lack of structure and scientific underpinning in their spontaneous methods. I imagine him, a quiet observer, perhaps noting how the fleeting nature of their work felt almost… unanchored, a beautiful chaos yearning for order. He wasn't content with merely capturing an impression; he sought a means to imbue the ephemeral with permanence, to ground subjective experience in objective, systematic principles. For Seurat, the Impressionists, despite their innovations, were too reliant on individual, transient perceptions, creating a subjective chaos that he believed could be elevated through systematic application. This intellectual conviction would become the bedrock of his unique artistic exploration. I can't help but wonder if his quiet, almost introverted nature drove this need for order in an otherwise chaotic world. He even showed an early interest in photography, perhaps seeing in it a parallel for systematically analyzing reality before reforming it on canvas – a kind of pre-visualization technique that appealed to his analytical mind, much like a photographer carefully composing a shot before pressing the shutter.

The Theoretical Framework: Orchestrating Color, Line, and Emotion

Seurat's quest for a systematic approach to painting led him to develop a holistic theoretical framework – almost a philosophy of perception itself. Ever wonder why certain colors evoke specific feelings, or how a simple line can feel joyful or melancholic? Seurat believed that artistic harmony could be achieved through a precise, scientific application of color and line, much like musical harmony. His studies were deeply influenced by the theories of several 19th-century scientists and aestheticians. This fascinating connection between visual elements and human psychology is something I often ponder in my own work: how can a simple line feel joyful or melancholic?

He meticulously studied the works of chemists like Michel Eugène Chevreul, whose Law of Simultaneous Contrast (1839) explained how adjacent colors intensify each other. Chevreul, working in a tapestry factory, observed that the perceived hue of a thread changed based on the colors woven next to it. He proposed that when two different colors are placed next to each other, each color will appear to tint the other with its complementary color. Think of it like a visual echo – red next to green makes the red 'borrow' a bit of green's complementary color, and vice-versa, making them both appear more intense! This phenomenon is partly due to retinal fatigue; your eye's cones, after perceiving one color, become momentarily less sensitive, making its complementary color appear stronger in the adjacent area. Seurat rigorously applied this, for instance, placing tiny dots of blue next to yellow to create a more luminous green optically, rather than mixing the pigments directly on the palette.

He also drew from the physicist Ogden Rood's analyses of complementary colors and their optical mixing. Rood's work showed how small, pure patches of color, when viewed from a distance, would mix in the eye, creating a more luminous effect than if the pigments were physically mixed on a palette. This is because light reflects directly from the pure colors rather than being partially absorbed by a pre-mixed, duller pigment. Seurat understood that by keeping colors separate on the canvas, he maximized their light-reflecting properties, creating an unparalleled luminosity. This idea of painting with pure light, rather than muddy pigments, was revolutionary.

Furthermore, Seurat absorbed Charles Henry's theories on the psychological effects of lines and hues. Henry suggested that specific directions of lines and types of colors could evoke particular emotional responses. According to Seurat's systematic application of these theories, which you can delve into further by exploring the definitive-guide-to-color-theory-in-art and the-psychology-of-color-in-abstract-art-beyond-basic-hues:

- Upward lines and warm colors (such as reds, oranges, and yellows) were associated with joy and gaiety. We see this powerfully in the festive, upward curves of the dancers in "Le Chahut."

- Downward lines and cool colors (blues, greens, and violets) conveyed sadness or calm. Consider the contemplative figures along the riverbank in "Bathers at Asnières."

- Horizontal lines and balanced colors implied tranquility and stability. "A Sunday on La Grande Jatte" famously employs a strong horizontal composition to create its sense of serene timelessness, as do his seascapes, such as "Seascape at Port-en-Bessin, Normandy."

This intellectual endeavor sought to distill emotion down to fundamental geometric and chromatic principles, creating what he hoped would be a universal language of aesthetic experience. It was about creating art that was both scientifically sound and emotionally resonant, a true synthesis of head and heart.

Beyond just the optical, Seurat's quest for order extended to a philosophical search for permanence in a transient world. While Impressionists celebrated the fleeting moment, Seurat sought to imbue those moments with an almost eternal quality, grounding subjective experience in objective principles. This intellectual rigor, this systematic approach to art, also resonated with the broader Symbolist movement of the late 19th century, which sought to express ideas and emotions through objective forms and symbols rather than direct representation. Seurat's quiet revolution was, in many ways, an attempt to bring a new kind of visual truth to a chaotic modern existence, perhaps even influenced by contemporary Positivist philosophies emphasizing scientific objectivity and observable facts. He was, in essence, an artistic manifestation of a positivist worldview, seeking to apply scientific methods to the seemingly subjective realm of aesthetics.

Neo-Impressionism: Theory into Practice

Seurat's quest for a systematic approach to painting led him to develop what became known as Neo-Impressionism, a movement fundamentally rooted in scientific principles of color and optics. At its core lay Divisionism (also known as Chromoluminarism, literally "color-light-ism"), the theory of separating individual colors into distinct brushstrokes or dots, which would then blend optically in the viewer's eye. Think of it as painting with light itself, rather than just pigment. Chromoluminarism specifically describes the effect of combining colors by separating them into pure components, allowing the eye to merge them into a new, more luminous color that appears almost to radiate light. This is distinct from simply mixing pigments on a palette, where the physical blending often dulls the resulting color. Pointillism emerged as the most visible and iconic technique for applying these Divisionist principles – the very method, I'd argue, that makes us lean in closer to his canvases, trying to unravel the magic. For a deeper dive into the specifics of this technique, I highly recommend exploring what-is-pointillism-in-art.

Consider, for instance, mixing blue and yellow paint to get green. Seurat's method involved placing tiny blue dots next to tiny yellow dots. When viewed from a distance, these dots optically combine to create a far more vibrant and luminous green than any pre-mixed pigment could achieve, as light is reflected directly from the pure colors rather than absorbed by a blended one. It’s remarkably similar to how pixels on a digital screen work, but hand-painted with painstaking precision. This wasn't just art; it was a meticulously controlled scientific experiment, a true pursuit of how how-artists-use-color can transcend mere aesthetics and become a phenomenon. He was a pioneer in applying scientific theory directly to artistic practice, methodically testing and refining his hypotheses on canvas after canvas.

This table offers a snapshot of how Seurat's vision diverged from his predecessors, highlighting his intellectual construction over spontaneous emotion:

Feature | Impressionism | Neo-Impressionism (Pointillism) |

|---|---|---|

| Brushwork | Visible, spontaneous, broad strokes | Small, distinct, uniform dots or dashes |

| Color Mixing | On the palette, often blended | Optical mixing in the viewer's eye |

| Approach | Capturing fleeting moments, subjective impression | Scientific, systematic, objective application of color theory |

| Subject Matter | Everyday life, landscapes, light effects | Similar, but with a focus on timelessness and formal structure |

| Emphasis | Light, atmosphere, immediate sensation | Luminosity, color harmony, structural composition |

| Core Philosophy | Spontaneous emotional response | Intellectual construction & objective analysis |

| Critique of Impressionism | Perceived as lacking scientific rigor, too subjective, fleeting | Sought to bring scientific rigor and permanence |

For those interested in the broader context of modern art's genesis, exploring the ultimate-guide-to-impressionism offers invaluable insights into the artistic landscape Seurat navigated and transformed. It’s a fascinating journey to see where art had been, and where Seurat decided it should go next, using his rigorous theoretical framework to orchestrate color, line, and emotion.

Seurat's Artistic Process: The Architect of Vision

To understand Seurat is to appreciate his unwavering commitment to a highly systematic artistic process – a process that was the direct embodiment of the theoretical framework we've just discussed. This wasn't an artist who simply picked up a brush and began; he was an architect of vision, a meticulous planner. I can only imagine the mental fortitude required for such an endeavor. His meticulous approach involved extensive preparatory work, beginning with numerous charcoal drawings to establish tonal values and compositional structure. These weren't mere sketches; they were finished works in themselves, demonstrating his mastery of line and shadow. He often used Conté crayon, a medium allowing for precise definition and rich tonal gradations, which was crucial for setting a strong linear and structural foundation for his paintings. Beyond Conté crayon, Seurat experimented with various types of canvases, often preferring a finely woven, smooth surface. This choice was deliberate: a smooth surface ensured that his meticulously applied dots remained distinct and didn't blur or merge into the canvas texture, maximizing the optical mixing effect. He also employed specialized, smaller brushes for precise dot application and carefully selected his oil paints for their pure pigment quality, as any impurity would dull the light-reflecting properties crucial to Divisionism.

Following the drawings, he would create small oil studies, or croquetons (from the French for "small sketches"). These croquetons were not just preliminary ideas; they were his mini-laboratories, allowing him to experiment with color relationships and optical mixing on a smaller scale. These studies allowed him to predict the optical effects before committing to the monumental canvases, essentially testing his scientific hypotheses. For "A Sunday on La Grande Jatte," for instance, he created over 60 such studies. Imagine the mental fortitude, the sheer patience required to plan and execute a painting this way, especially when using millions of tiny dots! It's a level of dedication that makes assembling IKEA furniture look like a spontaneous burst of creativity. Every figure, every tree, every shadow was carefully considered and placed, not by chance, but by deliberate, scientific intent. He even considered the frame as an integral part of the artwork, often painting a border of complementary dots directly onto the frame itself, or choosing a custom frame with specific color accents, to enhance the optical effect of the main image. This thoughtful integration ensured the artwork extended beyond the canvas, orchestrating a complete visual experience. It was an all-encompassing artistic endeavor, a testament to what disciplined focus can achieve.

Seurat's Masterpieces: A Chronology of Vision

Seurat's relatively short career produced an astonishing body of work, each piece a meticulous step in his ongoing scientific and artistic exploration. I find it fascinating to trace the evolution of his vision through these iconic canvases.

Bathers at Asnières (1884)

Often considered a precursor to "La Grande Jatte," "Bathers at Asnières" (1884) depicts working-class men by the Seine. While the Divisionist technique is still developing here – you might notice slightly broader strokes than in his later, more refined works – the painting undeniably showcases Seurat's early fascination with monumental forms and the play of light on solid figures. The classical composition and sculpturesque quality of the figures imbue the scene with a timeless dignity, contrasting the working-class subject matter with a traditional, almost reverential, artistic treatment. Its carefully constructed forms echo the classical masters, elevating the mundane to a quiet monument. I see in it a deliberate attempt to elevate the laborers with a classical weight usually reserved for mythological figures, perhaps subtly questioning societal hierarchies through art by dignifying the working class with a monumental presence often absent in contemporary art. By depicting common laborers with the formal grandeur traditionally reserved for historical or mythological subjects, Seurat gently but firmly challenged the artistic conventions that reinforced existing class divisions, suggesting that dignity and monumental beauty were accessible to all, not just the elite.

A Sunday on La Grande Jatte (1884-1886)

Seurat's most celebrated achievement, "A Sunday on La Grande Jatte" (1884-1886), is not merely a painting but a landmark event in the history of modern art. This monumental canvas, measuring over 2 by 3 meters, took Seurat two intense years to complete, following countless preparatory sketches and oil studies. It depicts Parisians enjoying a leisurely afternoon on an island in the Seine River, a subject seemingly aligned with Impressionist themes of modern life and leisure. But allow me to clarify, don't let that superficial similarity fool you; the execution tells a profoundly different story.

Yet, a closer examination reveals a profound departure. The figures, while engaged in leisure, are rendered with an almost architectural precision, appearing stiff, stylized, and strikingly static. They are frozen in time, rather than captured in a fleeting moment. This deliberate formality, coupled with the meticulous application of countless tiny dots of pure color, creates a scene that is both vibrantly alive with optical mixing and strangely still. For me, it offers a subtle, almost melancholic commentary on the rigidity of modern urban life, the growing anonymity in crowds, and the social stratification of the era. The presence of both bourgeois figures with their elaborate attire and parasols, alongside working-class individuals and even a soldier, suggests a calculated observation of Parisian society's distinct social classes, all coexisting in a seemingly harmonious yet rigidly separated public space. This rigid separation is visually reinforced by their lack of interaction, their almost identical profiles, and the distinct pockets they occupy on the island, each group largely oblivious to the others. It’s a snapshot of a society carefully arranged, much like the dots on his canvas, each individual distinct yet contributing to a larger, sometimes impersonal, whole. I find myself searching for individual narratives within the collective stillness, and the very act of seeing becomes a contemplative process. What emotions do you feel when you look at the stillness of these figures? Do you sense the quiet hum of individual lives amidst a calculated, almost architectural crowd?

Every element, from the top-hatted gentlemen and women with their parasols to the animals and the small girl in white, is meticulously composed. The painting is a masterclass in how order and unity can emerge from a multitude of individual points, demonstrating Seurat's profound understanding of compositional harmony and the scientific application of color theory. The overall effect is one of undeniable luminosity and a timeless serenity, a testament to the cumulative impact of painstaking precision. When I stand before it, I always feel a sense of meditative calm, an invitation to slow down and truly see not just the image, but the ingenious method behind it.

Seascapes and Coastal Scenes (1885-1890)

Seurat's captivating seascapes, such as "Le Bec du Hoc, Grandcamp" (1885), "Seascape at Port-en-Bessin, Normandy" (1888), and "The Channel of Gravelines, Petit Fort Philippe" (1890), allowed him to expand his experiments with light, shadow, and optical mixing to capture the shimmering effects of water and the subtle variations in sky and land. These coastal scenes often possess an incredible stillness, meticulously rendered with his signature dot technique, demonstrating his ability to apply his scientific system to evoke tranquil and atmospheric landscapes. He was particularly adept at capturing the subtle atmospheric conditions, using his dots to create the illusion of hazy skies, shimmering reflections on the water's surface, and the soft, diffused light of a coastal day. For instance, to depict mist, he might use a higher density of cooler, desaturated dots, while for shimmering water, he would employ contrasting warm and cool pure colors in dense, broken patterns to mimic the dance of light. The prominent use of horizontal lines in works like "Seascape at Port-en-Bessin" also exemplifies his theory that such lines induce a feeling of calm and stability, creating a sense of monumental serenity that belies the smallness of the dots. I find them almost meditative, like perfectly composed moments of silence where every ripple and cloud is precisely placed, orchestrated for visual harmony.

Later Works: Pushing the Boundaries of Movement and Emotion (1887-1891)

In his later works, such as "Circus Sideshow" (1887-88), "Le Chahut" (1889-90), and "The Circus" (1891), Seurat turned his attention to artificial light and indoor scenes, notably the vibrant world of Parisian entertainment. These settings were often depicted by his Impressionist contemporaries with spontaneous energy, but Seurat sought to capture their essence through his structured approach. "Circus Sideshow," often regarded as the first significant Pointillist painting depicting artificial light, captures the quiet drama of a fairground attraction at night, its figures stiffly arranged yet imbued with a profound stillness that belies the bustling atmosphere. It's a fascinating study of how formal arrangement can convey a sense of melancholic anticipation, a quiet theatricality. Under artificial light, the optical mixing effects could be even more pronounced, creating a heightened sense of luminosity and an almost surreal glow, presenting new challenges and opportunities for his meticulous dot application. Artificial light presented unique challenges because its spectral composition differs from natural sunlight, altering how colors interacted and how the eye perceived them, requiring Seurat to adjust his chromatic choices and dot density to achieve the desired effect of depth and vibrancy.

While still employing Divisionist principles, these paintings demonstrate an increasing emphasis on dynamic lines and exaggerated forms to convey movement and emotion. In "Le Chahut," for instance, the upward-sweeping lines of the dancers and the warm, vibrant colors evoke a sense of gaiety and theatrical energy, directly applying Charles Henry's theories on expressive lines. He masterfully uses reds and yellows to amplify the feeling of celebratory movement. "The Circus," with its swirling motion and a palette dominated by reds and yellows, pushes this even further, using his rigorous system to capture the very essence of a fleeting, energetic performance, rather than just its static appearance. They reveal his willingness to push the boundaries of his own rigorous system, integrating more expressive elements while maintaining his scientific approach to color and composition. Notably, "The Circus" remained unfinished at the time of his death. Examining its incomplete state offers a poignant glimpse into his final, evolving artistic intentions – we can see areas where dots are sparse, revealing the underdrawing, suggesting a mind still actively exploring, still pushing the limits of his own theories, hinting at new directions he might have taken towards an even more profound synthesis of structured form and vibrant emotion. Critics of his time were often perplexed by his radical approach, initially finding his work cold or mechanical. They often misunderstood the scientific intent, craving the immediate emotional expression of Impressionism rather than Seurat's calculated visual engineering.

Seurat's Enduring Legacy and Influence: A Quiet Seismic Shift

Georges Seurat's life was tragically cut short at the age of 31 in 1891, likely due to diphtheria or a form of meningitis. This untimely death, following a brief illness, left behind a relatively small yet incredibly significant body of work and an enduring "what if" in art history. One can only speculate on the further innovations he might have achieved, what new visual puzzles he would have posed had he been granted more time – perhaps delving further into abstraction, exploring different light sources, or even new subject matters. His impact, however, was immense, a quiet seismic shift that reverberated through the art world, largely gaining wider recognition through posthumous exhibitions that cemented his place in art history.

His intensely focused, almost monastic dedication to his craft contributed to the remarkable output achieved in such a short period. He maintained a relatively private life, keeping personal relationships, including one with his model and mistress Madeleine Knobloch – with whom he had two sons, Pierre-Georges and Claude-Marie – largely separate from his family and the wider art world. This singular focus underscores the profound mental fortitude required to execute millions of dots with such precision, often at great personal cost. It makes me wonder, what drives such an intense, almost obsessive, pursuit of an artistic ideal? Some might criticize Neo-Impressionism as too cold or mechanical, but few could deny the sheer intellectual power behind Seurat's vision. It was a vision that demanded every ounce of his being.

Direct Followers and Key Proponents

His closest collaborator and most ardent advocate was Paul Signac, who enthusiastically adopted and continued to develop Neo-Impressionism after Seurat's death, becoming its chronicler and chief theoretician. Signac not only applied the Divisionist technique to his own vibrant landscapes and seascapes but also codified the movement's principles in his seminal book, "D'Eugène Delacroix au Néo-Impressionisme" (From Eugène Delacroix to Neo-Impressionism), published in 1899. This text was instrumental in defining and disseminating Neo-Impressionist theory to a wider audience, ensuring Seurat's ideas lived on and influenced subsequent generations. Signac, along with artists like Camille Pissarro (who briefly adopted the style) and Henri-Edmond Cross, helped solidify Neo-Impressionism as a distinct, influential movement with its own principles and proponents.

Broader Artistic Currents

But Seurat's influence extended far beyond his direct followers, permeating the broader currents of modern art in ways that might surprise you.

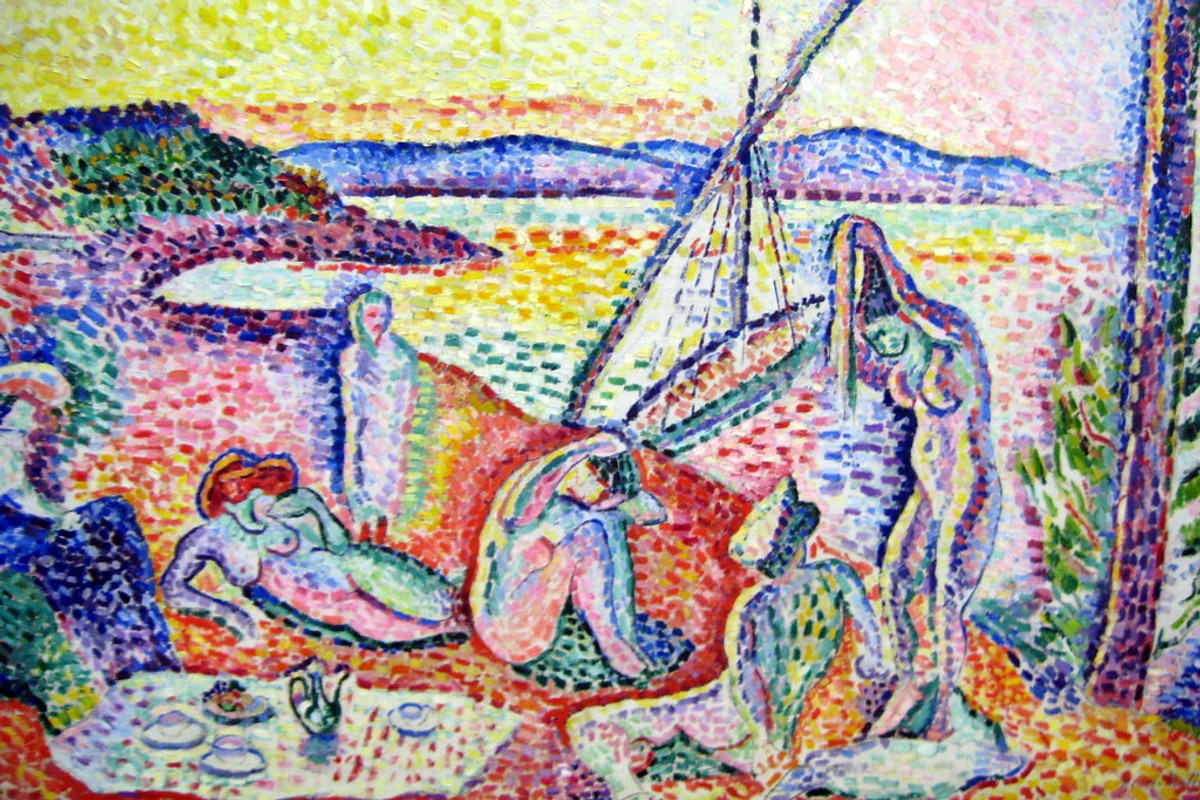

One notable example is the early work of Henri Matisse. His iconic "Luxe, calme et volupté" (1904) directly reflects Neo-Impressionist principles, with its visible dotted brushwork and vibrant color juxtapositions used to create a luminous, harmonious scene. This artwork, while a stepping stone to his explosive break into ultimate-guide-to-fauvism, clearly owes a debt to Seurat's systematic color application. Vincent van Gogh, too, experimented with systematic brushwork that echoed Divisionist concerns in some of his later pieces, as if finding a new kind of order in his own expressive chaos – for instance, his landscapes like "A Wheatfield with Cypresses" show a more controlled, almost patterned application of paint, though still intensely expressive. Seurat’s impact can even be traced to the structured compositions of ultimate-guide-to-cubism, where artists like Braque and Picasso broke down and reassembled forms. This analytical approach to visual reality, deconstructing perception into its constituent parts and presenting multiple viewpoints, echoes Seurat's desire to systematize and objectify the act of seeing.

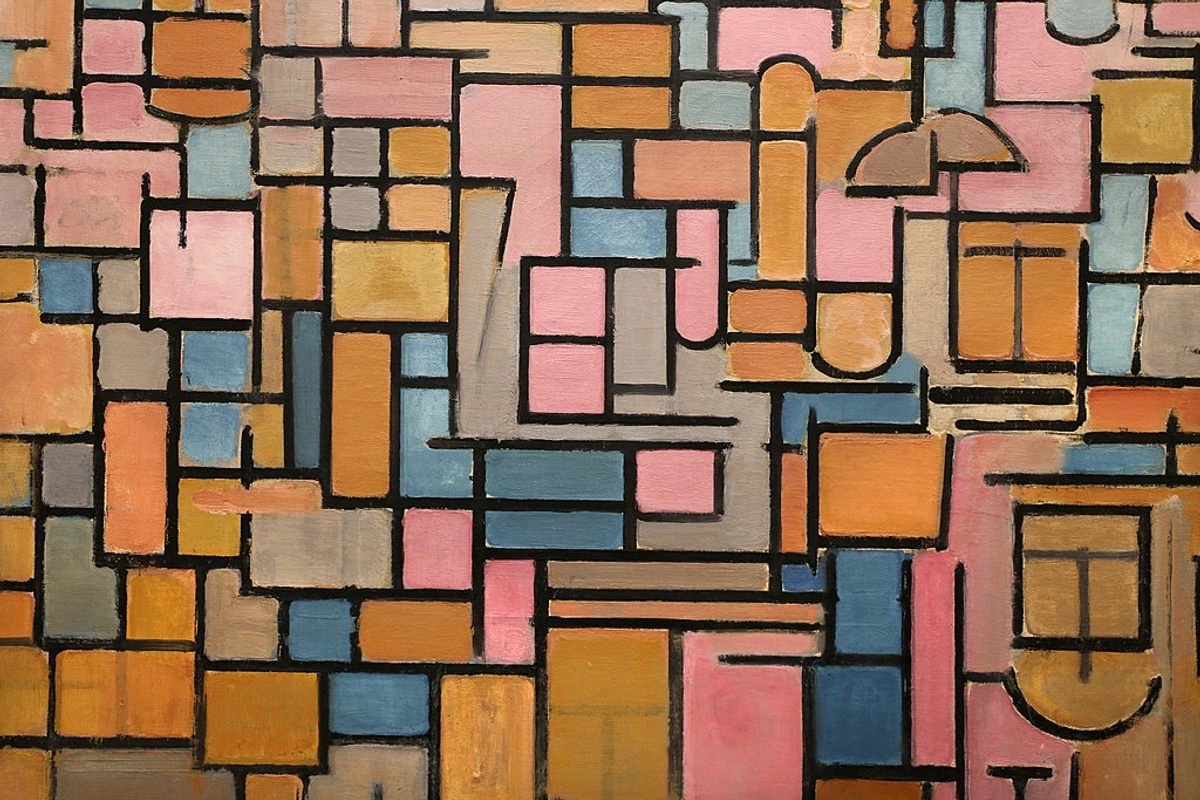

Moreover, the precise color theory explored by later abstract artists like Piet Mondrian, whose work (like "Tableau III: Composition in Oval") resonates with Seurat's quest for geometric and chromatic harmony, clearly owes a debt to Neo-Impressionism. Seurat’s analytical division of color laid a crucial foundation for the geometric abstraction that followed, seeking universal harmony through objective visual elements. Even some early graphic designers and illustrators, seeking novel ways to achieve luminosity and systematic color in print, drew inspiration from his innovations, realizing that small, distinct color elements could create vibrant illusions from a distance.

Neo-Impressionism, born from Seurat's analytical vision, compelled artists to approach color and form with a more scientific and intellectual rigor. It sparked a crucial dialogue within the art world: should art be primarily intuitive, or could it be meticulously constructed? Seurat decisively argued for the latter, irrevocably altering the trajectory of 20th-century art and paving the way for abstraction and diverse color experiments. His work, in a way, was a philosophical treatise disguised as painting. His precise, almost static compositions offered a striking counterpoint to the dynamic, fleeting captures of Impressionism, influencing how artists considered time and movement on canvas. For a broader perspective on artistic careers and historical context, consulting a general timeline can provide valuable insight into the brevity and immense impact of his life.

Conclusion: A Meticulous Visionary's Enduring Light

Georges Seurat remains an indispensable figure in the grand tapestry of art history. His work challenges viewers to engage with art on both an emotional and intellectual level, compelling us to observe with heightened awareness. He demonstrated that profound aesthetic statements could be achieved not through grand gestures, but through painstaking precision, one tiny dot at a time. Seurat transformed the perception of color from a mere aesthetic choice into a scientific phenomenon, proving that methodical experimentation and daring reconstruction of reality could yield unparalleled brilliance. His legacy is a testament to the enduring power of deliberate action and unwavering dedication in shaping artistic discourse. It’s a powerful reminder that sometimes, the quiet revolutionaries make the biggest noise, and that a deep understanding of structure can unleash new forms of beauty.

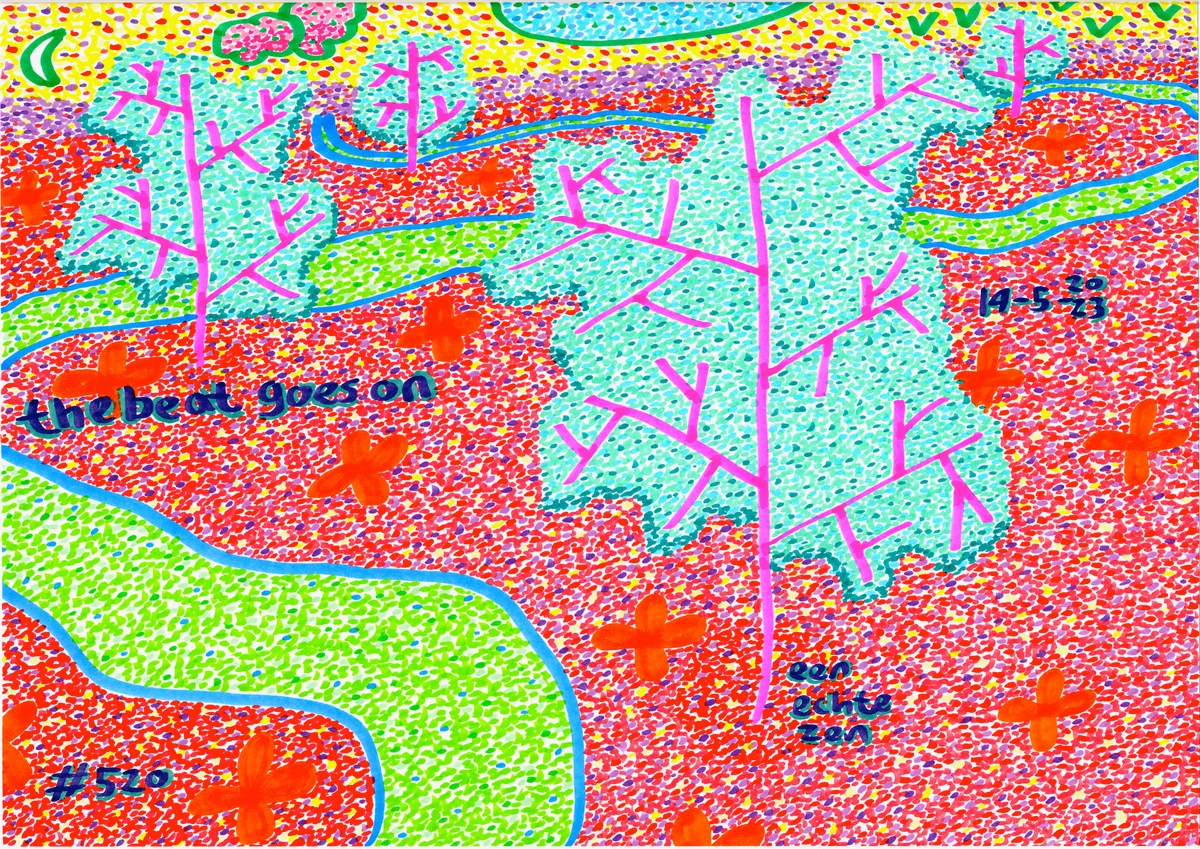

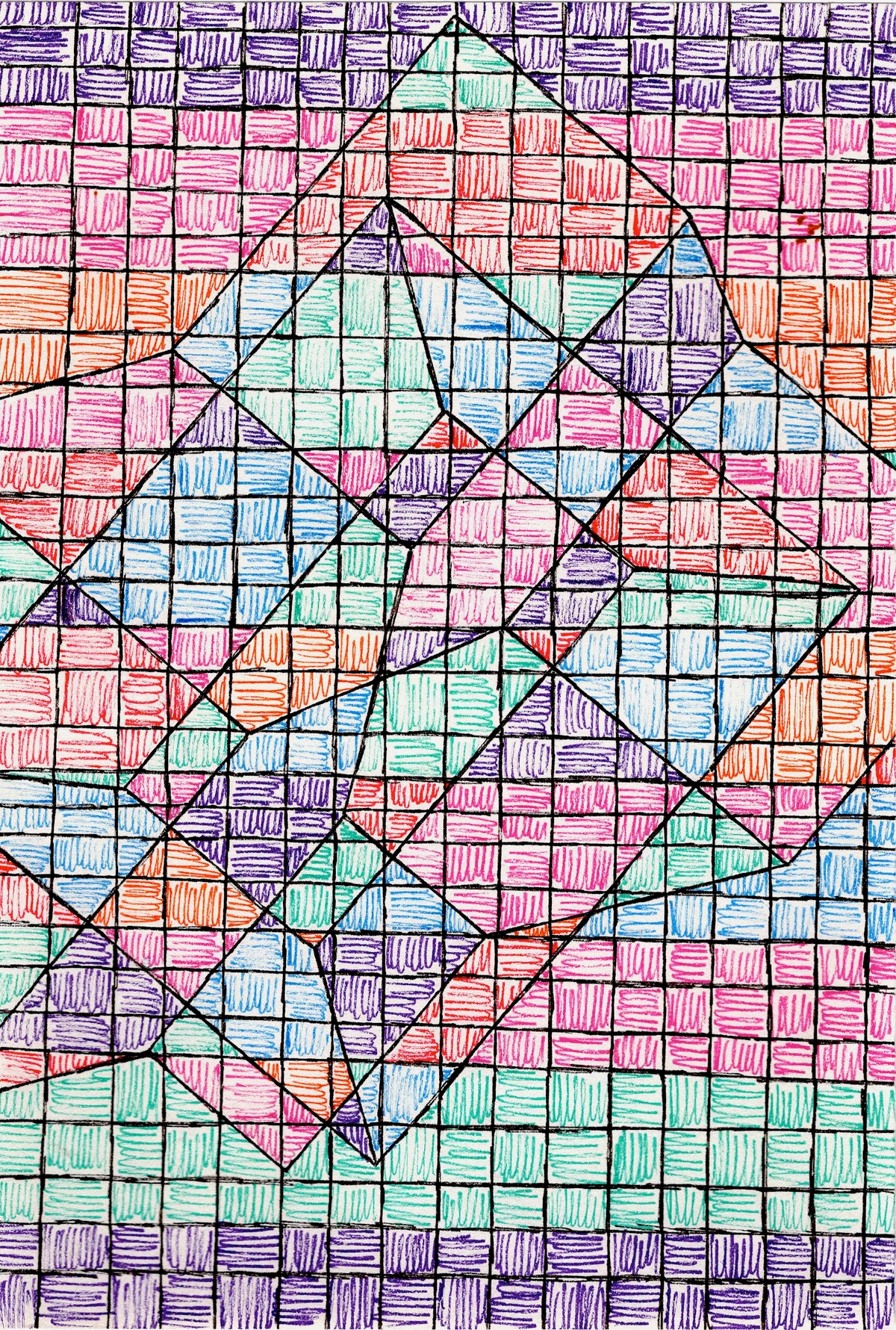

Contemporary artists continue to explore and reinterpret the principles of optical mixing and systematic color application. For example, artists like Zen Dageraad often draw from similar chromatic investigations, transforming intricate dot patterns into vibrant, abstract works that pulsate with light and achieve profound optical blending, directly echoing Seurat's foundational inquiries into perception and luminosity. Other artists, from Op Art practitioners like ultimate-guide-to-victor-vasarely-the-father-of-op-art to digital color theorists, echo Seurat's fundamental questions about how the eye and mind construct an image from discrete elements. You might explore current exhibitions at the den-bosch-museum to find contemporary art that resonates with these principles, or consider acquiring pieces that draw from similar chromatic investigations via [buy]. These engagements offer a glimpse into how Seurat's meticulous vision continues to resonate in today's art world, inviting new interpretations of color, light, and form. Next time you see a Seurat, don't just glance – truly see the millions of tiny decisions that make up his grand vision, and perhaps even try a simple optical mixing experiment yourself; you might be surprised by the vibrancy you can create when you understand the science of seeing!

Frequently Asked Questions About Georges Seurat

This section addresses common inquiries regarding Georges Seurat and his revolutionary artistic contributions. I find these questions often provide a wonderful entry point into understanding his complex genius, and as a curator, I'm always keen to make art accessible. Dive in, and let's unravel some mysteries! What else is there to know about this quiet revolutionary?

What is Pointillism?

Pointillism is an art technique developed by Georges Seurat, characterized by the application of small, distinct dots or strokes of pure color in patterns to form an image. This technique is the most visible application of Divisionism (or Chromoluminarism), the broader theory of separating individual colors. Pointillism relies on the viewer's eye to optically blend these colors, resulting in a more luminous and vibrant effect than traditional mixing on a palette. It's truly a collaboration between the artist's hand and the viewer's brain, a deliberate science of perception, much like the pixels on a screen. For a comprehensive look, explore our guide on what-is-pointillism-in-art.

What are Georges Seurat's most famous paintings?

Georges Seurat's most famous painting is "A Sunday on La Grande Jatte" (1884-1886), a true icon. Other significant works include "Bathers at Asnières" (1884), "Circus Sideshow" (1887-88), "Le Chahut" (1889-90), "The Channel of Gravelines, Petit Fort Philippe" (1890), and "The Circus" (1891). Each represents a different facet of his meticulous exploration into light, form, and emotion, showcasing his progression from monumental figures to dynamic, artificially lit scenes.

How long did Seurat work on A Sunday on La Grande Jatte?

Seurat dedicated approximately two intense years to "A Sunday on La Grande Jatte," working from 1884 to 1886. This period involved extensive preparatory charcoal drawings and over 60 oil sketches, culminating in the painstaking application of millions of individual dots of paint. It was an undertaking that speaks volumes about his dedication to his vision and his scientific approach – a truly monumental effort for a monumental artwork, essentially a long-form scientific experiment on canvas.

How did Seurat die?

Georges Seurat died tragically young at the age of 31 in 1891. The exact cause is generally attributed to diphtheria or a form of meningitis, potentially exacerbated by overwork and stress, though some historical sources also mention infectious angina. His untimely death was a profound loss for the art world, cutting short a career that promised even greater innovations and leaving us to wonder what more he might have achieved. It's a poignant reminder of the fragility of even the most brilliant artistic lives.

How did Seurat's scientific approach differ from academic art training?

While academic art training at institutions like the École des Beaux-Arts emphasized scientific principles of anatomy, perspective, and classical composition, Seurat's scientific approach went further. He applied scientific theories of color perception and optics (from Chevreul, Rood, Henry) directly to the application of paint, systematically breaking down color into its constituent parts for optical mixing. Academic training focused on realistic representation; Seurat aimed for a more objective, deconstructed, and optically vibrant reality. He was, in essence, trying to engineer vision itself, rather than merely replicate it.

What were the limitations of the Pointillist technique?

The Pointillist technique, while offering unparalleled luminosity and a sense of timelessness, did have limitations. Its meticulous nature was incredibly time-consuming, limiting the number of works Seurat could produce and demanding immense patience from the artist. Some critics also found it to be rigid or mechanical, lacking the spontaneous emotional expression they associated with other movements. Additionally, the optical blending works best from a specific viewing distance, which can be challenging to control in a diverse gallery setting. It was a compromise between scientific rigor and fluid artistic expression.

Did Seurat consider himself a scientist or an artist?

Seurat considered himself an artist, but one who rigorously employed scientific methods to achieve his artistic vision. He saw art and science not as separate disciplines, but as complementary paths to understanding and representing reality. His aim was to create art that was both aesthetically profound and intellectually sound, grounded in objective principles rather than mere subjective impulse. He was, in essence, an artist-scientist, a visual engineer, constantly experimenting with the mechanics of human perception.

What is the difference between Pointillism and Impressionism?

The fundamental difference lies in their approach to color, brushwork, and underlying philosophy. Impressionism employs visible, spontaneous brushstrokes to capture fleeting light and atmosphere, often mixing colors on the palette, focusing on a subjective "impression." Pointillism, a key technique of Neo-Impressionism, utilizes small, distinct dots of pure color applied systematically to the canvas. It relies on the viewer's eye to optically blend colors, aiming for greater luminosity, structured composition, and a scientific basis rather than a subjective emotional response. One seeks the fleeting, immediate moment; the other, a timeless, calculated, and optically constructed phenomenon. It's the difference between a spontaneous sigh and a meticulously composed symphony, or perhaps the difference between a candid snapshot and a carefully engineered photograph.

What were the main criticisms of Pointillism/Neo-Impressionism during Seurat's lifetime?

During Seurat's lifetime, Pointillism and Neo-Impressionism faced several criticisms. Many critics found the technique to be cold, rigid, and mechanical, arguing that its systematic approach stifled emotional expression and spontaneity, which were highly valued by the Impressionists and many other contemporaries. Some also dismissed it as overly scientific or theoretical, lacking the intuitive touch they expected from art. The painstakingly slow process limited the number of works Seurat could produce, and the need for a specific viewing distance for optimal optical mixing was also seen as a practical limitation in gallery settings. They often failed to grasp the intellectual depth and the revolutionary intent behind his scientific rigor.

Who did Georges Seurat influence?

Georges Seurat profoundly influenced his contemporaries and subsequent artists. His most direct follower was Paul Signac, who formalized and continued the Neo-Impressionist movement, along with artists like Camille Pissarro and Henri-Edmond Cross. Other notable artists influenced by his color theories and techniques include Henri Matisse (particularly in his early Fauvist works like "Luxe, calme et volupté"), Vincent van Gogh (who experimented with systematic brushwork), Piet Mondrian with his structured abstraction, and various artists associated with Symbolism, Cubism (ultimate-guide-to-cubism), and the broader development of Modernism, all of whom engaged with his analytical approach to art. His ripple effect was truly significant, setting the stage for much of 20th-century abstraction and even impacting early graphic design principles. You can see echoes of his systematic thought in many forms of contemporary art today.

How is Seurat’s approach to art scientific?

Seurat’s approach to art was scientific in its rigorous application of optical and color theories. He studied the works of scientists like Michel Eugène Chevreul, Ogden Rood, and Charles Henry to understand complementary colors, optical mixtures, and the psychological effects of lines and hues. He systematically separated colors into individual dots, believing they would blend more vibrantly in the viewer's eye than if mixed on a palette, essentially treating the canvas as a laboratory for color and light experiments. He was a keen observer of natural phenomena and sought to formalize these observations into a repeatable, objective artistic methodology, even considering the potential impact of photography on composition and perspective. It was less about spontaneous expression and more about controlled, observable results, making art a truly intellectual pursuit and a profound act of visual engineering.

Connect with Seurat's Vision

If Seurat's meticulous approach to color and form has resonated with you, I invite you to delve deeper into the interplay of light and perception in contemporary art. Explore current exhibitions at the den-bosch-museum to find modern works that echo Seurat's foundational inquiries, or perhaps even discover pieces that draw from similar chromatic investigations via [buy]. Engaging with art, whether through studying history or experiencing contemporary creations, is a continuous journey of discovery, much like Seurat's own lifelong quest to master the science of seeing.