Pointillism Unveiled: Optical Science, Dot Art, & Modern Legacy

Dive into Pointillism's optical science, from Seurat's meticulous dots to its pioneering Neo-Impressionist vision. Explore key artists, characteristics, technical challenges, and its vibrant influence on contemporary art and perception.

Pointillism Unveiled: Optical Science, Dot Art, & Its Enduring Legacy

I remember the first time I really saw a Pointillist painting. I mean, I’d seen pictures, of course, but it wasn't until I stood inches away, then stepped back, that the magic actually clicked. Up close, it was just… dots. A kaleidoscope of tiny, separate specks of color, a bit like my laundry pile on a Monday morning, a chaotic collection of individual items. But then, as I stepped back, those chaotic dots suddenly coalesced into a vibrant, coherent image, shimmering with an intensity I hadn't expected. It genuinely felt like a trick, a visual illusion played just for me.

And honestly, that’s when I fell a little bit in love with Pointillism. It's not just a style; it's an invitation to engage, a secret whispered between the artist and your brain. It asks you to participate, to do some of the work, and in return, it rewards you with something truly special. My initial fascination quickly sent me down a rabbit hole, eager to understand the science, dedication, and even the subtle psychology behind it. So, join me on this journey as we demystify Pointillism, exploring its scientific heart, the dedication of its pioneers, and understanding its enduring whisper in the art world – a whisper that still sparks fascination today, and one I've found holds a surprising key to understanding the vibrant dance of colors in much of my own abstract work.

The Big Dotty Idea: Optical Mixing and the Science of Sight

But how did tiny dots, these individual specks of pigment, coalesce into those shimmering masterpieces I found so captivating? It all boils down to optical mixing, the ingenious core of Pointillism. At its heart, Pointillism is an art technique where small, distinct dots of pure color are applied in patterns to form an image. Sounds simple, right? But the genius lies in the 'pure color' part. Instead of mixing colors on a palette (the traditional way, which, let's be honest, can be quite satisfying), Pointillists placed primary and secondary colors side-by-side on the canvas. The actual blending happens not on the artwork itself, but in your eye. It's a bit like a chef preparing spices – each distinct flavor is there, but your palate does the real blending to create a complex taste sensation. Wild, right? But with optical mixing, that's essentially what happens; the colors blend in your eye.

Your brain, being the clever thing it is, takes all those tiny, individual color dots and blends them together into new, luminous hues. It’s a bit like how a TV screen or your phone's display works; countless tiny pixels of red, green, and blue combine to create every image you see. The crucial difference here is that your perception is the mixer. The pixels on a screen emit light, blending physically, but with Pointillism, your brain does the heavy lifting, stitching those separate points into a cohesive whole, creating something that wasn't physically there on the canvas. For me, it's a profound reminder that art isn't just what's on the canvas, but also what happens in the space between the canvas and the viewer. It's a conversation. And speaking of conversations, it makes you wonder about the subjectivity of it all, doesn't it? What one eye perceives as a shimmering orange, another might see slightly differently depending on lighting, individual biology, or even variations in color perception. It's a subtle reminder that the artwork truly comes alive in the unique landscape of each viewer's mind.

This scientific approach wasn't some happy accident; it was deeply rooted in the color theories of the time. Artists like Seurat avidly studied the writings of chemists such as Michel Eugène Chevreul, who explored the concept of simultaneous contrast. Chevreul showed how colors placed next to each other profoundly affect one another's appearance. A red dot next to a green dot, for instance, wouldn't just sit there politely; they would vibrate, each making the other seem more intense and luminous. Before this, many artists relied on intuition or traditional color mixing rules, not fully grasping the dynamic interplay of adjacent hues. Physicists like Ogden Rood also influenced Pointillists with their work on how the human eye perceives light and mixes colors. They were essentially working with additive color mixing, similar to light itself, where combining pure colors results in brighter, more luminous hues. Think of spotlights in a theater: red, green, and blue light overlapping create white light. This is fundamentally different from subtractive color mixing, which is what happens when you mix paint on a palette. With paint, the pigments absorb certain wavelengths of light, and as you mix more colors, more light is absorbed, resulting in darker, duller tones – often ending up in a murky brown if you mix too many.

By meticulously applying pure, complementary colors (like blue and orange, or red and green) in small dots side-by-side, Pointillists aimed to achieve maximum luminosity and vibration, trusting the viewer's eye to do the complex blending work for a shimmering, almost vibrating effect. For example, by placing tiny dots of pure red and pure green close together, your eye doesn't see distinct red and green; instead, it optically blends them to perceive a vibrant yellow or sometimes a warmer brown, depending on the proportion and intensity. This goes beyond just making colors "vibrate"; it's about actively generating new hues in the viewer's mind. It's amazing to think how much of what we see is influenced by what's next to it, isn't it? It makes you re-evaluate every color choice, and truly understand how artists use color.

These scientific principles weren't just theoretical curiosities; they were the bedrock upon which a new artistic revolution was built by a select group of visionary artists.

The Visionaries Behind the Dots: Seurat, Signac, and the Neo-Impressionist Revolution

Pointillism wasn't some random happy accident; it was a deliberate, almost scientific, movement that emerged from Neo-Impressionism in the late 19th century. This was a time of immense scientific and industrial progress, where people were fascinated by systems, logic, and observable phenomena. Beyond industrial might, new fields like psychology were exploring human perception, and the burgeoning art of photography was challenging traditional notions of capturing reality, pushing artists to rethink how they represented the world. This era fostered a broader cultural movement towards positivism, a belief in scientific knowledge as the ultimate authority, which profoundly influenced art. Artists felt a pull to understand the mechanics of vision and apply scientific rigor to their canvases, rather than merely replicate reality. But who were the masterminds behind this dotty revolution, and what drove them to such meticulous precision? The undisputed grand master of this technique was Georges Seurat, and his friend, Paul Signac, was a close second. They were tired of the fleeting, spontaneous nature of Impressionism (which, don't get me wrong, I adore for its immediacy, but it lacked a certain… rigor for them).

Neo-Impressionism, and Pointillism within it, wasn't just about a new technique; it was almost a philosophical stance. Artists like Seurat sought to bring a sense of order, permanence, and universal harmony to art through a systematic, almost mathematical application of paint. It was a reaction against what they perceived as the superficiality and transient emotionalism of Impressionism. They wanted art to be intellectually rigorous, built on observable scientific principles, not just fleeting impressions. This systematic approach, emphasizing structure and objective principles over subjective feeling, makes it a fascinating precursor to many later abstract art movements, laying groundwork for explorations into pure form and color.

Seurat, in particular, was fascinated by color theory and the science of optics. He avidly studied the writings of chemists like Michel Eugène Chevreul, who explored simultaneous contrast, and physicists like Ogden Rood, whose work on color perception deeply influenced Seurat's approach. He believed he could create more vibrant, luminous colors by applying tiny dots of pure pigment rather than mixing them traditionally. He called his method chromoluminarism (or divisionism), which simply means he was obsessed with light and color, and dividing them into their purest forms for the eye to blend. Imagine sitting there, meticulously placing dot after dot, knowing that the real magic wouldn't happen until someone stood back and let their eyes do the work. That takes a special kind of dedication, something I can certainly appreciate (though my own patience often wears thin when a new idea sparks and I just want to see it finished!).

His most famous work, "A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte," exemplifies this monumental dedication. This single painting, spanning over 10 feet wide, contains literally millions of meticulously placed dots, taking Seurat two years to complete—a staggering testament to the immense time commitment the technique demanded. Its initial reception was mixed; some critics found its scientific precision cold and its figures rigid, lacking the emotional expressiveness of more traditional painting. Indeed, this strict methodology posed a fascinating dilemma: while it promised precision, some critics argued it could stifle expressive freedom, potentially leading to a perceived sterility, a sense of being overly mechanical, or a lack of emotional intensity if not handled with immense skill. It's a subtle tension, I think, where the system, if not carefully wielded, risks dictating the art rather than serving the artist's deepest expression.

While Seurat and Signac were the pioneers, other artists like Camille Pissarro, Henri-Edmond Cross, and Maximilien Luce also experimented with or were influenced by these divisionist principles. Cross, for instance, developed a softer, more fluid application of dots, pushing the technique towards a more decorative and harmonious aesthetic, proving that the "dot" could be more than just a precise scientific tool. Beyond the potential for rigidity and the risk of appearing mechanical, the technique was incredibly time-consuming, limiting the output of artists and sometimes leading to a certain flatness if not handled with exceptional artistic judgment and a deep understanding of composition in art. It makes you wonder, what sacrifices are artists willing to make for their vision?

Beyond the Brushstroke: The Enduring Characteristics of Pointillism

So, when I step back and really ponder Pointillism, what are the defining features that make these 'dot paintings' truly sing? For me, it boils down to a few core aspects that have always resonated, even in my own very different artistic journey:

The Language of Pure Color and Precision

Pointillism is, at its core, a language of carefully chosen, unmixed hues.

- Pure, Unmixed Color: As I mentioned, no muddying colors on the palette. It's all about letting the individual pigments sing on the canvas. This results in an incredible vibrancy; the colors seem to glow from within, almost like they're backlit. It's a stark contrast to how many of us instinctively reach for the mixing palette, isn't it? It makes you rethink basic assumptions about how artists use color.

- Systematic Application: This wasn't chaotic splattering (though I do love a good splatter now and then!). Seurat and Signac were incredibly methodical. Every dot had its place, contributing to the overall composition in art and the intended optical effect. It’s less about spontaneous emotion and more about controlled precision – a bit like a complex mathematical equation, but a beautiful one. There was also the challenge of maintaining consistent dot size and spacing, which required immense discipline and a steady hand.

- Optical Mixing: This is the party trick, the core concept. The colors don't physically blend; they blend in your perception. This gives Pointillist works a unique, shimmering quality that’s hard to achieve with conventional brushwork. The surface buzzes with life as your eye constructs the final image.

- Luminosity and Vibrancy: The result of pure, unmixed colors undergoing optical blending is an unparalleled luminosity. Pointillist paintings often appear brighter and more vibrant than those made with traditional color mixing, almost as if the light emanates from the canvas itself, creating a palpable visual 'vibration' that captivates the viewer.

The Dance with the Viewer

Pointillism isn't just painted; it's completed in your mind, fostering a unique interaction.

- Visible Texture: While the goal was optical blending, the physical application of distinct dots creates a subtle, tactile texture on the canvas. This slightly raised surface can add another layer of visual interest, inviting closer inspection. But it's more than just a tactile element; this subtle physical texture actually enhances the optical blending. Think about it: the tiny shadows and highlights on each individual dot, however minuscule, play with the light, contributing to the shimmering, almost three-dimensional quality of the final image. It's as if the surface itself is breathing, contributing to that vibrant 'buzz' you feel. It truly makes you appreciate the role of texture in art.

- Viewer Participation & Psychological Effect: This is perhaps one of the most compelling, if subtle, characteristics. The active role demanded of the viewer in mentally blending the colors can create a profound, almost meditative engagement with the artwork. There's a wonder that comes from seeing individual dots coalesce into a coherent image, making the viewing experience itself a creative act, a quiet dialogue between the canvas and your mind. It’s a profound reminder that the art isn't just on the surface; it's completed in your brain, creating a sense of active discovery and a more intimate connection with the artist's intent.

The Artist's Unwavering Commitment

Creating Pointillist masterpieces demanded a rare blend of scientific rigor and monastic patience.

- Time-Consuming Nature: This is perhaps one of the most significant, if often overlooked, characteristics. Creating a large-scale Pointillist work like Seurat's "La Grande Jatte" took years, not months. The meticulous placement of countless tiny dots demanded unparalleled patience and dedication, severely limiting the output of artists and requiring a profound commitment to the process. I mean, can you imagine trying to hit just the right shade of blue, dot by dot, for two years straight? My coffee would be cold by lunchtime on day one! It truly demanded a monk-like dedication that, frankly, leaves me in awe.

- Subject Matter: Pointillists often chose subjects that allowed for calm, ordered compositions, such as serene landscapes, Parisian leisure scenes, and urban life. The deliberate and slow nature of the technique suited these subjects perfectly, providing a sense of timelessness rather than fleeting impression, and a framework for their structured approach. These were not subjects for quick, emotional sketches, but for carefully constructed visual harmony.

- Scale: Achieving the full, shimmering optical effect often necessitated larger canvases. These grander scales allowed for the multitude of dots to be appreciated both up close and from a distance, immersing the viewer in the intricate detail and the final blended image.

Speaking of dedication, the Pointillists were equally meticulous about their materials and tools. They typically used traditional canvases, often prepared with an exceptionally smooth gesso or primer. This wasn't just aesthetic; a smooth surface was absolutely crucial to ensure the precise, consistent application of their tiny, uniform dots, preventing any interference from canvas texture that could disrupt the delicate optical blend. For the dots themselves, they favored pure, high-quality pigments, ensuring the vibrancy and luminosity necessary for the optical mixing effect. To achieve the required precision, artists often employed fine-tipped brushes or even the blunt end of a paintbrush handle to apply their countless tiny marks with unwavering consistency.

This meticulousness, this almost scientific approach to art, is what I find so compelling. It's a reminder that sometimes the most impactful results come from a deep understanding of the fundamentals, even if your ultimate goal is wild abstraction. So, next time you see a painting with a million tiny details, take a moment to consider the sheer dedication behind it. What fundamental truths about art and perception do these tiny dots reveal to you?

My Journey with Dots: Abstract Echoes of Pointillist Principles

While I don't consider myself a Pointillist in the traditional sense, the principles, the very spirit of Pointillism, absolutely weave their way into my art. My abstract work often explores the interplay of vibrant hues and tactile textures, creating a sense of depth and movement through layered forms and energetic marks. The idea of discrete elements coming together to form a larger, vibrant whole? That’s something I explore constantly in my contemporary, colorful abstract paintings. I’m fascinated by how individual brushstrokes or color blocks interact to create movement, depth, and emotion without necessarily depicting a recognizable form. It’s about the pure joy of color and how it dances in your eye, much like those tiny dots do in a Seurat.

For instance, in a piece like 'Chromatic Vibrations' (a hypothetical title, of course!), I might use small, deliberate dabs of electric blue alongside fiery orange, or perhaps deep indigo next to a warm yellow. My intention isn't to represent a city scene, but to make those colors vibrate against each other, creating that same optical shimmer you see in a classic Pointillist canvas. From a distance, the intense blue and orange might blend into a shimmering grey-brown, while the indigo and yellow could produce a rich, perceived green – all without me ever mixing them on my palette. It's about how their energetic conversation creates a larger, dynamic narrative for the viewer. It's funny, sometimes I still catch myself fussing over a single brushstroke, thinking about how it will impact the whole, and a little voice whispers, 'Channel your inner Seurat!'

My work might not use tiny, uniform dots, but the careful placement of color, the way I layer hues to create optical effects, and how I build complexity from simplicity – that's a direct conversation with the legacy of artists like Seurat. Sometimes, it's about the juxtaposition of intense colors that vibrate against each other, creating a perceived glow. Other times, it's the subtle textural build-up from repeated marks. It’s about building an immersive experience for the viewer, inviting them to complete the picture in their own minds. If you're curious about my own explorations in color and abstraction, feel free to browse my art for sale – you might just see some distant cousins of those Pointillist dots! It’s this profound interaction between individual elements and holistic perception that I find so endlessly fascinating, and it's a principle I carry into every canvas.

Pointillism's Enduring Whisper: A Quiet, Vibrant Revolution

Pointillism, though a relatively short-lived movement in its purest form, cast a long shadow. It influenced subsequent generations of artists, demonstrating that art could be both intellectually rigorous and visually stunning. It pushed the boundaries of how we think about color and perception. It paved the way for movements like Fauvism, with its bold, unmixed colors, directly inspiring artists to break free from traditional representation and explore the emotional impact of pure, liberated hues. Moreover, the active participation demanded of the viewer in optically blending the colors can create a more profound, almost meditative viewing experience, a psychological resonance that lingers.

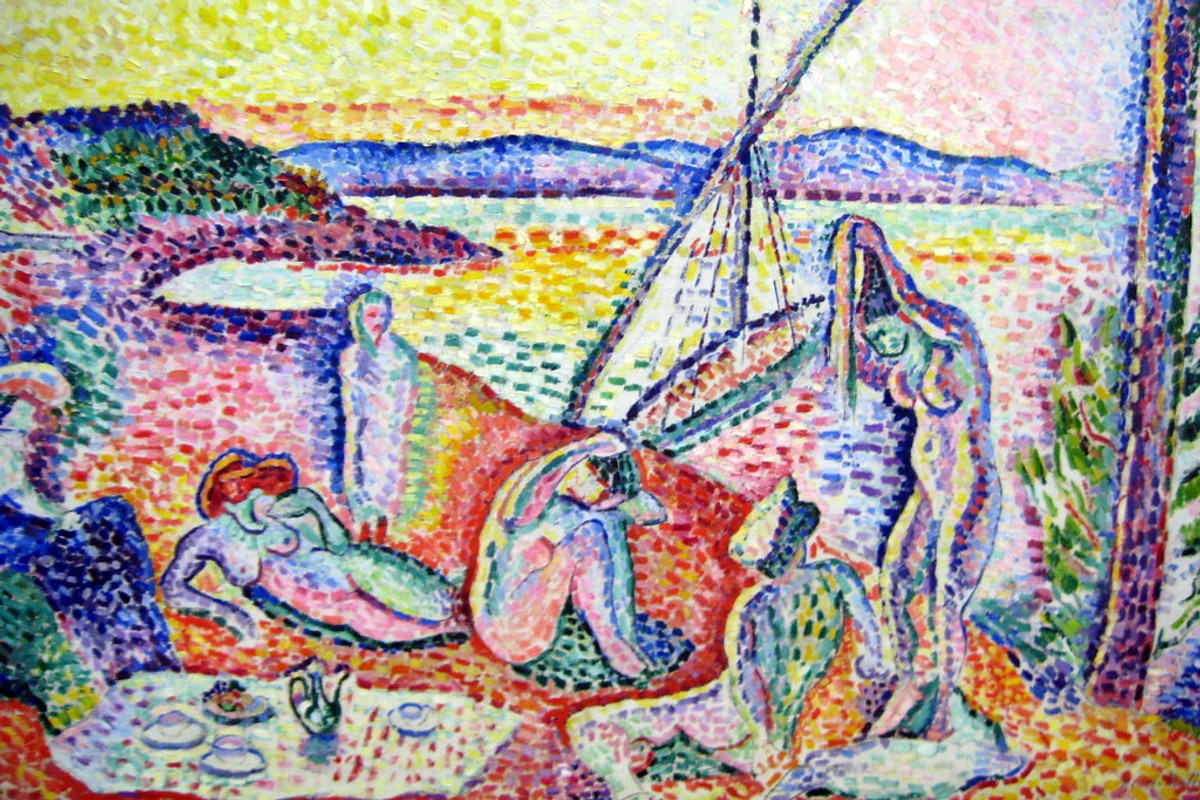

The Fauves, for instance, wholeheartedly embraced the Pointillist's revolutionary concept of using pure, unmixed colors directly on the canvas to achieve maximum vibrancy. However, their intent diverged significantly. They consciously rejected the meticulous, scientific application of tiny dots, finding its rigorous system too restrictive. Instead, artists like Henri Matisse in his "The Joy of Life" and André Derain employed broad, expressive brushstrokes, using these liberated, intense colors not for optical precision, but for raw emotional expression and decorative effect, prioritizing spontaneity and feeling over methodical application. Where a Pointillist might use red and green dots to optically blend into a shimmering yellow for a precise effect, a Fauve artist might splash pure, unmixed red next to pure green for the sheer jarring emotional impact and visual intensity. It was a stylistic departure that owed much to Pointillism's groundbreaking color theory while forging its own path. If you want to dive deeper into this fascinating offshoot, check out our ultimate guide to Fauvism.

Beyond Fauvism, Pointillism's principles echoed in various ways. Orphism, for example, explored color interactions and simultaneity, building on the idea that color itself could be the primary subject. Even artists developing earlier forms of abstract art movements found inspiration in the scientific approach to color, adapting it to their own non-representational ends. Pointillism, in essence, taught us that sometimes the most profound visions emerge not from grand gestures, but from the meticulous arrangement of the smallest, purest elements, inviting us to look closer, think deeper, and ultimately, see more.

Even today, its principles echo in digital art (think of every pixel on your screen as a tiny, deliberate dot!), graphic design, textile design, and scientific imaging. Pixel art, dithering in early computer graphics, and certain generative art algorithms directly mirror the Pointillist approach of building complex images from discrete, colored units, each one a conscious decision. When we look at the immersive, dot-filled environments of contemporary artists like Yayoi Kusama, while her motivations are distinct from Seurat’s scientific rigor, there's an undeniable spiritual connection in the overwhelming visual power created by countless individual points. It’s that same sense of wonder, that immersion in a world built from simple, repeated forms. So, the next time you encounter a piece of art, whether it's composed of tiny dots or sweeping gestures, ask yourself: what small, deliberate choices are at play, and what larger conversation are they inviting you into? If you ever find yourself wandering through a museum, like perhaps my own museum in 's-Hertogenbosch, keep an eye out for those seemingly simple dots; they tell a much bigger, more vibrant story than you might expect.

FAQ: Your Dot-to-Dot Guide for Burning Questions

Got more questions about those intriguing dots? Here’s a quick dot-to-dot guide to some common queries:

Who invented Pointillism?

Primarily, Georges Seurat is credited with inventing Pointillism, though his close collaborator and fellow artist Paul Signac also played a crucial role in developing and popularizing the technique, often preferring the term divisionism.

What's the difference between Pointillism and Impressionism?

Oh, this is a good one! Impressionism focused on capturing fleeting moments and the effects of light with loose, spontaneous brushstrokes, often blending colors directly on the palette. Pointillism, in contrast, was systematic and scientific, applying color theory with meticulous dots of pure color to achieve luminosity through optical mixing, often resulting in more structured compositions. Impressionists painted what they saw right now; Pointillists crafted a visual system for your eye to complete.

Is Pointillism still used today?

While pure Pointillism as a dominant art movement had its heyday, its principles absolutely live on! Many contemporary artists, myself included, draw inspiration from its color theory and optical mixing concepts, even if they don't use the strict dot technique. You'll see echoes of it in digital art, graphic design (think pixels!), textile design, and even in how some street artists approach murals. It's less about strict adherence and more about the enduring lessons it taught us about color and perception.

What kind of canvases or surfaces did Pointillists use?

Pointillists generally preferred traditional canvases, often preparing them with a particularly smooth gesso or primer. Why so smooth? Because this meticulous precision was crucial for applying tiny, uniform dots without interference from canvas texture. A rough surface would have disrupted the consistent application and the delicate optical blending, potentially muddling the intended visual effect rather than creating luminosity. While larger canvases allowed for the full immersive effect – enabling the intricate detail to be appreciated both up close and from a distance – smaller panels were also used for studies, ensuring that whether grand or intimate, the surface supported the exactitude required for their optical experiments.

Why is it called Pointillism?

The term "Pointillism" was actually coined by art critics in the late 1880s to describe the technique. It comes from the French word "point" or "pointiller," meaning "to dot" or "to stipple." It was initially used somewhat derisively, implying a mechanical or overly systematic approach, but the artists themselves, particularly Seurat, often preferred the more scientific-sounding terms chromoluminarism or divisionism.

What were the main technical challenges for Pointillist artists?

Beyond the sheer time commitment, Pointillist artists faced several formidable technical hurdles. Achieving consistent dot size and spacing across large canvases required immense discipline and a steady hand. They often used small, round brushes or even the blunt end of a paintbrush handle to apply the dots uniformly. Moreover, correctly anticipating the optical mixing effect was a formidable challenge. If colors were chosen or placed incorrectly, the intended luminosity could easily be lost, or the blending in the viewer's eye might result in muddy, dull tones rather than the desired vibrant, shimmering hues. Another critical challenge, less about application and more about longevity, was the potential for pigment degradation or fading over time. Using pure pigments, while great for luminosity, meant that artists had to be acutely aware of their stability. Many pigments used in the late 19th century were not as lightfast as modern ones. If unstable pigments were used, or if the works were exposed to harsh light, the vibrant, luminous effects could unfortunately diminish significantly, altering the artist's original intention and disrupting the delicate optical blend. It truly was a delicate balance of scientific theory and artistic intuition, demanding not only patience but also a deep understanding of color relationships and human perception to ensure the dots sang rather than just sat there.

As I look at my own abstract canvases today, I often see the faint, enduring echoes of Pointillism’s quiet revolution. That meticulous attention to individual elements, the belief that small, deliberate choices can coalesce into something far greater than the sum of their parts, and the profound invitation for the viewer to participate in the art – these are the lessons I carry forward. It's a reminder that truly impactful art often comes from a deep understanding of its foundational elements, no matter how abstract the final expression. So, whether you're standing before a Seurat masterpiece or an abstract explosion of color, remember the power of the dot, the pixel, the individual mark, and the vibrant conversations they spark in the landscape of our perception.