Caring for Watercolor Paintings: A Comprehensive Preservation Guide

Discover how to preserve your precious watercolor paintings from light, moisture, and time. I share my essential tips on framing, displaying, and storing your art for lasting beauty.

The Essential Guide to Watercolor Preservation: Care, Display, and Long-Term Protection

I remember the first time I saw a watercolor painting that had faded. It was years ago, a beautiful landscape, once vibrant, now a ghost of its former self. My heart sank a little, not just for the lost beauty, but for the artist's effort and the collector's joy, diminished by something as simple as light. That experience truly hammered home for me: watercolors are delicate. They demand a certain tenderness, a particular kind of guardianship. And if you've invested your time, passion, or money into these luminous pieces, you absolutely want to ensure they stay as brilliant as the day they were created. This isn't just about protecting an object; it's about preserving a moment, a vision, and the magic of a medium that dances with light and water. But it's more than that, isn't it? It’s about being a steward of fleeting beauty, a keeper of light-infused dreams, and a guardian of cultural heritage. This isn't just a guide; it's the definitive guide to becoming a true guardian of your most cherished watercolor art, ensuring its legacy for generations. We'll dive into the nuances of archival framing, ideal display environments, strategic storage, and the vital role of professional conservation, covering everything a collector or artist needs to know for long-term preservation and care.

The Unseen Battle: Why Watercolors Are So Vulnerable

Why are watercolors considered so fragile? Well, it mostly comes down to their very nature and chemical composition. Unlike oils or acrylics, which form a relatively robust, continuous polymer film, watercolor pigments are essentially microscopic particles of inorganic or organic compounds, finely ground and suspended in a water-soluble binder, most commonly gum arabic. This binder is derived from acacia trees and, while excellent for creating transparent washes, offers very little physical protection to the pigment particles themselves. These thinly applied pigments then settle into the porous fibers of the paper, making them incredibly responsive and vulnerable to external factors like light, moisture, and airborne pollutants. It's a delicate dance of light and pigment on paper, where the very elements that bring it to life can also lead to its slow demise. Understanding this inherent fragility—this lack of a truly protective 'skin'—is the first step towards becoming a diligent steward. For a broader perspective on various artistic mediums, you might find our guide on the definitive guide to paint types for artists insightful.

- Pigments and Light: Many watercolor pigments, especially older or lower-grade ones, are not entirely lightfast. This means prolonged exposure to various forms of electromagnetic radiation—primarily ultraviolet (UV) light but also intense visible light—can break down their chemical structure, leading to fading, dulling, or even a complete color shift. It's a cruel irony that something meant to capture light is so susceptible to its damaging effects. Historically, artists often contended with notoriously fugitive pigments—think carmine, indigo, or older alizarin crimson—that would visibly shift or disappear over decades. Imagine creating a masterpiece only for its vibrant hues to become ghosts within a generation! The ephemeral nature of some historical pigments like cochineal (carmine) or gamboge (a vibrant yellow) reminds us of the constant battle artists and collectors face against time. The chemical bonds within the pigment molecules are literally broken down by the energy from light photons, leading to irreversible changes in color and intensity. While modern chemistry has gifted us with far more stable options, with pigments synthesized for superior endurance and purity, understanding lightfastness ratings is still paramount. The most common standard is the ASTM (American Society for Testing and Materials) scale, which rates pigments from I (Excellent Lightfastness) to V (Very Poor Lightfastness). Another widely used system, especially in Europe, is the Blue Wool Scale, which uses a rating of 1 (very poor) to 8 (excellent). Even certain natural light components, beyond just UV, can degrade colors over time, creating a cumulative effect. Always check these ratings when selecting or acquiring artwork if longevity is a priority. I always suggest seeking out professional-grade watercolors known for their lightfastness; it’s a non-negotiable for lasting work. For artists, the choice of pigment is an act of foresight, a silent promise of endurance to your future collectors. And for collectors, knowing these ratings can be the difference between a lasting masterpiece and a faded memory.

Understanding Pigment Lightfastness Ratings

Rating System | Lightfastness | Description |

|---|---|---|

| ASTM I | Excellent | No perceptible change in 100 years of museum exposure. |

| ASTM II | Very Good | Slight change in 100 years of museum exposure. |

| ASTM III | Fair | Noticeable change in 50 years of museum exposure. |

| ASTM IV | Poor | Considerable change in 20 years of museum exposure. |

| ASTM V | Very Poor | Extreme change or fading in 10 years of museum exposure. |

| Blue Wool 8 | Excellent | Fading resistant for over 100 years. |

| Blue Wool 1 | Very Poor | Fading resistant for less than 5 years. |

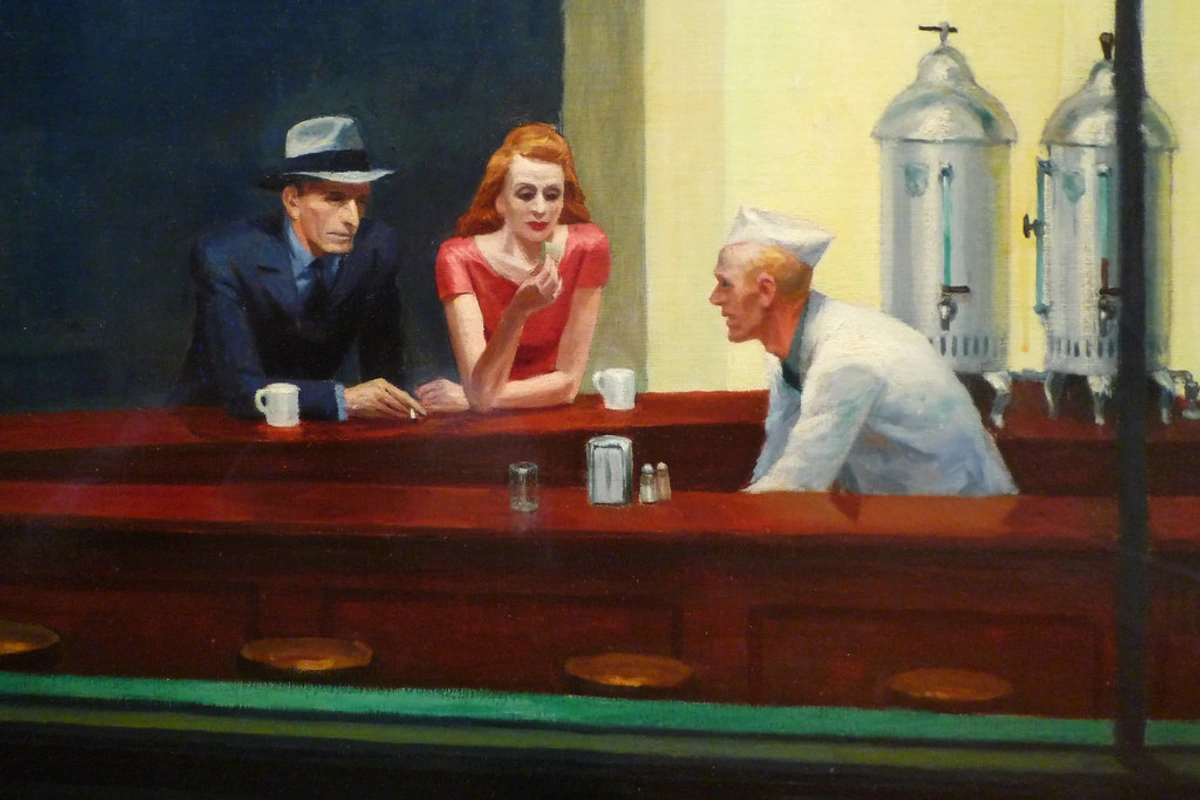

credit, licence

- Paper and Environment: The paper itself, usually cellulose-based, is susceptible to acidity, mold, and physical damage. Humidity can cause buckling, while dryness can make it brittle. Dust, pollution, and even oils from our hands can degrade the paper over time. It's a delicate ecosystem, really, and we're the stewards. The presence of lignin—a natural polymer found in wood pulp—is a common culprit for acidity in non-archival papers, leading to yellowing and embrittlement. Lignin naturally breaks down over time, releasing acids that actively damage cellulose fibers, eventually turning the paper brittle and prone to breakage. Beyond this, airborne pollutants from urban environments—such as ozone, sulfur dioxide, and nitrogen oxides—or even off-gassing from common household items like fresh paint, new furniture, or cleaning products can contribute to the slow, insidious decay of paper fibers. Even microscopic mold spores, seeking a food source and moisture, can proliferate rapidly, leaving irreversible stains and weakening the paper structure. The type of paper also matters immensely: consider the surface texture (hot press for smooth, cold press for subtle texture, rough for highly textured), the weight (thicker, heavier papers like 300lb or more are generally less prone to buckling from humidity fluctuations than lighter weights like 140lb), and the sizing, which affects absorbency. Historically, papers often contained impurities or were manufactured using acidic processes, making them inherently unstable over time. Choosing the right foundation is key for longevity; if you're an artist, always opt for acid-free and 100% cotton rag paper to give your work the best fighting chance against time. Look for terms like 'archival quality,' 'museum grade,' or 'pH neutral.' For collectors, assume any older work might be on acidic paper unless proven otherwise, and handle it with extra caution. For an artist, selecting the right paper is like choosing the canvas for a lasting legacy; it impacts not just the artistic execution but the very lifespan of your creation. You can find more insights into selecting the best foundations in articles like this one on best watercolor paper for artists review.

You might be thinking, "Oh no, my precious piece!" Don't worry, it's not a death sentence. With the right care, your watercolors can last for generations, looking almost as fresh as the day they were painted. It's all about creating the right protective environment. We also need to be aware of the less obvious threats.

Beyond the Basics: Invisible Threats

Beyond the well-known culprits of light and humidity, there are subtle, often unseen dangers lurking. Pests like silverfish, booklice, and various beetles have an unfortunate appetite for paper and cellulose-based materials. They thrive in dark, undisturbed, and often humid environments. Their presence can lead to chewed edges, tunnels through the paper, and unsightly droppings, which, trust me, are not fun discoveries. Then there are the airborne chemicals: volatile organic compounds (VOCs) off-gassing from building materials (like certain particle boards or glues), fresh paints, new furniture, carpets, and even common cleaning supplies or air fresheners. These invisible assailants can subtly react with paper and pigments over time, causing discoloration, embrittlement, or accelerating degradation through chemical reactions. Even dust, seemingly innocuous, can be abrasive, and when combined with humidity, can become a breeding ground for micro-organisms, leading to insidious mold growth. It's a reminder that true preservation requires vigilance against a multitude of silent enemies, a constant awareness of the microscopic world that can impact your macroscopic art. Simple preventative measures like regular, gentle dusting, ensuring good air circulation, and avoiding direct exposure to new household items that might off-gas are surprisingly effective. Implementing a basic Integrated Pest Management (IPM) strategy, focusing on cleanliness and monitoring, is a cornerstone of long-term preservation at home.

The Indispensable Value of Archival Materials: An Investment in Longevity

I know, the word "archival" often comes with a higher price tag, and it's tempting to cut corners. But let me be blunt: with watercolors, it's a false economy. Investing in museum-grade materials for framing and storage isn't just about protecting an object; it's about preserving an investment, a piece of cultural heritage, or simply something that brings you profound joy. Think of it as preventative medicine for your art. A few extra dollars spent upfront can save you hundreds, if not thousands, in potential restoration costs down the line – costs that might not even fully reverse the damage. For artists, using archival materials isn't merely a recommendation; it's a mark of professionalism, integrity, and deep respect for your craft and your collectors. It signals that you value the longevity of your creations. For collectors, it's about ensuring the legacy and lasting beauty of the art you bring into your life, safeguarding its intrinsic, aesthetic, and financial value. It’s the foundational layer of true preservation, and frankly, I wouldn't do it any other way. Trust me, the regret of seeing a cherished piece degrade due to non-archival choices far outweighs the initial savings.

Common Non-Archival Culprits and Archival Alternatives

Beyond the paper and matting, the frame itself matters. Not all wood is created equal in terms of archival quality. Certain woods, particularly softwoods like pine or fir, can contain natural acids and resins that off-gas over time, potentially damaging artwork. Hardwoods like maple or oak are generally more stable, but should still be properly sealed.

Frame Material | Archival Suitability | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| Softwoods (Pine, Fir) | Poor; high acidity, off-gassing | Avoid direct contact, ensure proper sealing. |

| Hardwoods (Maple, Oak) | Moderate; more stable, but still sealable | Use with archival barrier and seal. |

| MDF/Particle Board | Poor; high VOCs from glues and resins | Avoid; significant off-gassing risk. |

| Metal (Aluminum, Steel) | Excellent; inherently inert, no off-gassing | Highly recommended. |

| Polymer/Plastic | Good; if 'archival grade' or inert | Verify material is inert and pH neutral. |

Non-Archival Material | Problem | Archival Alternative | Key Benefit of Alternative |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardboard | Acidic, leaches into artwork, yellows paper. | 100% Cotton Rag Board / Alpha-Cellulose Board | pH neutral, lignin-free, stable. |

| Standard Wood Frames | Off-gassing acids, can stain mat/art. | Sealed Hardwood / Metal Frames | Inert, prevents chemical migration. |

| Regular Window Glass | Minimal UV protection, allows fading. | UV-Filtering Glass / Acrylic | Blocks 97-99% of harmful UV rays. |

| Pressure-Sensitive Tape | Adhesives degrade, stain, become irreversible. | Japanese Paper Hinges + Wheat Starch Paste | Reversible, stable, non-damaging. |

| Newsprint/Kraft Paper | Highly acidic, rapid degradation. | Acid-Free Tissue / Mylar Sleeves | Inert barrier, protects from contact and pollutants. |

The Cornerstones of Watercolor Protection

Protecting a watercolor painting boils down to a few core principles: shielding it from harmful light, meticulously managing its environment, and robustly protecting it physically. Think of it as building a tiny, perfect sanctuary for your art, a micro-museum designed for optimal preservation. This comprehensive approach is what truly distinguishes diligent stewardship from casual ownership.

1. The Power of Framing: Your Art's First Line of Defense

This is, without a doubt, the most critical step for any watercolor you intend to display. Proper framing is not just about aesthetics; it's a meticulously engineered protective enclosure. I often tell people it's like putting your art in a tiny, customized fortress, a climate-controlled bubble against the ravages of time and environment.

- Archival Matting and Backing: This is non-negotiable. You absolutely must use acid-free and lignin-free materials for anything that touches your artwork. This includes the mat board and the backing board. Why? Because regular paper products contain acids that will slowly, relentlessly, "burn" and discolor your artwork over time, a process often called "mat burn" or "acid migration." It starts as a subtle yellowing and then... well, it's not pretty. I've seen it happen, and it's heartbreaking. So, only museum-grade (100% cotton rag) or conservation-grade (purified alpha-cellulose) boards are acceptable here. These materials are processed to remove harmful acids and lignin, ensuring they won't leach damaging chemicals into your artwork. Lignin, for those curious, is a complex natural polymer found in wood pulp that breaks down over time, releasing acids that turn paper yellow and brittle—it's the silent enemy of paper longevity. Don't skimp on this; it's the closest material to your precious art. Furthermore, ensure proper hinging is used to secure your artwork to the mat or backing. This involves using reversible, archival Japanese paper hinges and wheat starch paste or methyl cellulose adhesive, never tape directly on the artwork. This allows the artwork to expand and contract naturally with minor environmental changes without buckling or tearing. Think of it as giving your art room to breathe without letting it wander, ensuring its long-term stability within the frame. You can learn more about paper choices in articles like this one on best watercolor paper for artists review, and for general supplies, check out essential watercolor supplies for beginners.

Types of Archival Boards for Framing

Board Type | Material Composition | Key Characteristics | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| 100% Cotton Rag Board | Pure cotton fibers | Highest archival quality, naturally acid-free, stable. | Museum-grade framing for valuable/sensitive artworks. |

| Alpha-Cellulose Board | Purified wood pulp (lignin-free) | Conservation-grade, less expensive than rag, acid-free. | General archival framing for most artworks. |

| Archival Foam Core | Polystyrene core, acid-free paper surfaces | Lightweight, rigid, used for backing and spacers. | Backing large artworks, creating internal frame spaces. |

| Fluted Polypropylene | Inert plastic | Moisture-resistant, rigid, pH neutral. | Backing in humid environments, long-term storage. |

Hinging Methods for Works on Paper

Proper hinging is a subtle but crucial aspect of archival framing. The goal is to secure the artwork while allowing for natural expansion and contraction, preventing stress and damage.

Hinging Method | Description | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|

| T-Hinge | Two short strips of Japanese paper attached to the top verso of the artwork, then to the backing board. | Strong, common, invisible from front. | Requires careful placement, can create slight impression on thin paper. |

| Pendant Hinge | A single strip of Japanese paper attached to the top verso of the artwork, allowing it to hang freely. | Minimizes stress, suitable for thicker papers. | Less common, may allow more movement. |

| Strap Hinge | A long strip of Japanese paper extending the length of the artwork, attached to the backing board. | Very strong, ideal for large or heavy works. | More visible from verso, requires more material. |

| Corners/Slits | Mylar corners or slits cut into mat to hold artwork without adhesive contact. | Completely reversible, no adhesive on artwork. | Can be less secure for heavy works, corners can crease. |

Always use archival, acid-free Japanese paper and reversible adhesives like wheat starch paste or methyl cellulose. Avoid pressure-sensitive tapes at all costs, as their adhesives degrade over time, causing irreversible staining and damage.

- Spacer or Mat: Creating the Essential Air Gap A mat serves a crucial purpose beyond aesthetics: it creates an essential air gap between the surface of the artwork and the glazing (glass or acrylic). This is vital because moisture can condense on the inside of the glass, and if it touches the watercolor directly, it can cause the paper to stick, pigments to transfer, or mold to grow. The mat board itself acts as a buffer. If you prefer a "float mount" or no mat, a hidden spacer made of archival material (like archival foam core or clear acrylic strips) must still be used to maintain this essential air gap. A float mount is a beautiful display technique where the artwork appears to float within the frame, showcasing its deckled edges or full sheet. While aesthetically pleasing, it still requires that crucial separation from the glazing, often achieved with a hidden foam core spacer or risers. The principle remains the same: no direct contact between art and glass. This isn't just a design choice; it's a functional imperative; it prevents irreversible damage. Think of it as a personal space bubble for your art, a microclimate of protection. This air circulation within the frame package is also critical for dissipating any minor off-gassing from the artwork or frame materials, preventing it from accumulating and accelerating degradation, and creating a stable mini-environment.

- Glazing (Glass or Acrylic): Your Primary UV Shield This is where you battle UV light head-on. Glazing is not just about keeping dust off; it's a powerful, scientifically engineered shield against the insidious effects of light. But it's not a one-size-fits-all solution; the type of glazing you choose makes all the difference.

- UV-Filtering Glass/Acrylic: Invest in glass or acrylic that offers robust UV protection. This isn't just about blocking some UV; it's about minimizing the impact of the most damaging spectrum of light, specifically UVA, UVB, and UVC radiation, with UVA and UVB being the most detrimental to pigments and paper. Museum glass or conservation clear acrylic can block 97-99% of harmful UV rays. This is your primary weapon against fading, embrittlement, and discoloration. Standard window glass, for all its transparency, offers very little protection, often blocking only a minimal percentage of UV radiation. It's important to remember that UV light doesn't just fade colors; it can also cause the paper itself to yellow and become brittle, accelerating the aging process from within. Think of UV-filtering glazing as a critical line of defense, slowing down the inevitable march of time, but not stopping it entirely. It’s like wearing the highest SPF sunscreen on a sunny day – essential, but you still seek shade, right? Cumulative exposure matters, even with the best protection, and every bit of UV blocked extends the life of your artwork.

- Understanding UV Radiation and its Shielding: It's helpful to remember that UV light is part of the electromagnetic spectrum. UVA (long-wave, 315-400 nm) penetrates deeply, UVB (medium-wave, 280-315 nm) causes sunburn and direct DNA damage, and UVC (short-wave, 100-280 nm) is largely blocked by the ozone layer but can be present in artificial sources. Specialized glazing is engineered with microscopic layers that either absorb these specific wavelengths or incorporate coatings that reflect them, preventing them from reaching the artwork. This is a marvel of material science, giving your art a much-needed invisible shield. This is often an area where even seemingly knowledgeable people misunderstand; they think any glass will do, but it simply won't.

- Anti-Reflective Coatings: While not directly protective, anti-reflective coatings significantly improve viewing pleasure, making the art pop without distracting glare. It's a quality-of-life upgrade for your artwork, allowing the true colors and subtleties to shine through. Imagine gazing at a serene landscape only to have your own reflection staring back at you – anti-reflective coatings eliminate that visual interruption, ensuring the art remains the sole focus. Some museum-grade options combine both high UV filtration and exceptional anti-reflective properties, offering the best of both worlds, truly allowing the art to be seen as the artist intended.

Glazing Terminology at a Glance

Term | Purpose / Benefit | Key Feature | Additional Detail |

|---|---|---|---|

| UV Filtering | Protects artwork from fading and degradation. | Blocks 97-99% of harmful UV light. | Crucial for paper-based art and sensitive pigments. |

| Anti-Reflective | Reduces glare for optimal viewing. | Special coatings minimize reflections. | Enhances visual clarity, makes glass seem |

- Acrylic vs. Glass: Weighing Your Glazing Options Acrylic (Plexiglas) is lighter and more shatter-resistant, making it a good choice for larger pieces, especially in high-traffic areas, earthquake zones, or homes with children or pets. It's also safer to ship. However, it can scratch more easily than glass and tends to build static electricity, which can attract dust and fine pigment particles over time. Special anti-static cleaners for acrylic are a must, and avoid wiping it with dry cloths. To further mitigate static, some conservators recommend gently wiping acrylic with a soft, slightly damp (with distilled water) lint-free cloth, as moisture temporarily dissipates static charges. Glass, while heavier and brittle, is generally more scratch-resistant and doesn't build static as readily. The choice often comes down to specific needs, display environment, and budget. For very large works, the weight of glass can make handling and hanging impractical, making acrylic the superior choice despite its drawbacks. Each material has its place, but understanding their characteristics is key to making an informed decision.

Backing Boards and Sealing: Completing the Protective Enclosure

Once framed, the back of the frame should be meticulously sealed with archival tape (such as gummed paper tape or self-adhesive polyester tape) to create a comprehensive barrier against dust, insects, and environmental fluctuations. This isn't just a nicety; it completes the protective enclosure, creating a stable micro-environment within the frame that helps regulate humidity and keeps out unwelcome guests like silverfish or dust mites, which unfortunately have a taste for paper. A well-sealed frame is a truly robust fortress. This also helps to prevent acidic gasses from the wall or surrounding environment from entering the frame package. Ensuring a proper, breathable archival backing board behind your artwork further enhances this protection. Options include conservation corrugated plastic (fluted polypropylene), archival foam core (acid-free, with a polystyrene core), or even museum board for extra rigidity. The choice depends on the size and weight of the artwork, as well as the desired level of protection against punctures and impacts. The backing board, in conjunction with the frame sealing, prevents environmental contaminants from migrating into the frame package from the back.

Archival Tapes for Frame Sealing

Not all tapes are created equal when it comes to long-term preservation. Choose tapes specifically designed for archival use to avoid future damage. These tapes form a critical part of the frame's defensive barrier, preventing ingress of dust, insects, and atmospheric pollutants, while remaining stable and reversible over time.

Tape Type | Description | Key Benefit | Avoids | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gummed Paper Tape | Water-activated, pH-neutral paper tape with a stable adhesive. | Strong, durable, completely reversible. | Pressure-sensitive tapes, acidic adhesives. | Often used for sealing dust covers, provides strong bond. |

| Self-Adhesive Polyester | Clear, inert polyester film with a stable acrylic adhesive. | Transparent, strong, moisture-resistant. | Tapes with rubber-based adhesives (which degrade). | Ideal for creating a smooth, invisible seal. |

| Linen Tape | Woven linen cloth with a pH-neutral, reversible adhesive (often gummed). | Very strong, ideal for heavier frames/backs. | Non-archival cloth tapes. | Provides robust structural support for heavy backing boards. |

| Tyvek Tape | Made from high-density polyethylene fibers, strong, water-resistant. | Breathable yet protective, durable. | Non-archival duct tapes. | Good for humid environments, allows slight vapor exchange. |

Choosing the Right Frame Material: More Than Just Aesthetics

While the matting and glazing are crucial, the frame itself also plays a role. Traditional wooden frames can sometimes off-gas acidic compounds, especially if they are made from unsealed, non-archival wood or processed wood products like MDF (medium-density fiberboard) which use glues that contain volatile organic compounds (VOCs). If you're custom framing, inquire about the wood type and if it's been properly sealed or painted with an inert, low-VOC finish to prevent any potential interaction with the artwork. Look for frames made from hardwoods, or those with stable, inert finishes. Metal frames are often a safer bet in this regard as they are inherently inert and do not off-gas. Think of the entire framing package as a system where every component should support the longevity of your art. Beyond this, consider the weight and structural stability of the frame material in relation to the artwork's size and the chosen hanging method. A flimsy frame, regardless of how archival its internal components are, risks damaging the artwork if it's not robust enough to support its weight or if it's hung precariously. The structural integrity of the frame is a foundational aspect of its protective function.

Common Framing Problems and Solutions

Problem | Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Mat Burn/Acid Migration | Non-archival mat/backing touching art. | Re-frame with 100% cotton rag or alpha-cellulose matting and backing. |

| Buckling/Waviness | High humidity, improper hinging, or insufficient air gap. | Re-frame with proper hinging, spacers, and ensure stable humidity. Conservator may flatten. |

| Mold Growth | High humidity, lack of air circulation, condensation. | Professional conservation treatment. Ensure proper sealing and environmental control. |

| Fading/Discoloration | UV light exposure. | Use UV-filtering glazing. Avoid direct sunlight. |

| Artwork Sticking to Glass | No air gap, high humidity causing condensation. | Re-frame with a mat or spacer to create an air gap. |

| Dust/Insects Inside Frame | Improperly sealed frame. | Re-seal the frame with archival tape. Clean interior with professional assistance if needed. |

Seeking Expert Framing Advice: When to Call the Pros

Look, framing is an art in itself, and a professional framer is truly a specialist in their field. If you have a particularly valuable, sentimentally cherished, or oversized piece, don't hesitate to consult with a professional, experienced art framer. They can guide you through the labyrinth of archival practices, material choices, and aesthetic considerations for your specific artwork and display environment. Their expertise is invaluable in creating that perfect, protective sanctuary. When choosing a framer, look for someone who emphasizes archival materials, uses reversible techniques, and can explain the 'why' behind their recommendations. Don't be afraid to ask about their experience with paper-based artworks, and ask for examples of their work. For more insights, you might find this Q&A with an expert art framer helpful, as it demystifies the process. A good framer is a partner in preservation, not just a service provider. In fact, think of them as a primary care physician for your art – they can diagnose potential issues and prescribe the best course of preventative treatment before more serious intervention (like conservation) is needed.

Questions to Ask Your Professional Framer

To ensure your artwork receives the best possible care, here are some key questions to ask when consulting with a professional framer:

- "What archival materials do you use for matting and backing?" (Look for 100% cotton rag or purified alpha-cellulose.)

- "What kind of glazing do you recommend for UV protection?" (Aim for 97-99% UV blocking.)

- "What hinging method will you use, and with what adhesives?" (Ensure reversible, archival Japanese paper hinges and wheat starch paste/methyl cellulose.)

- "How will the frame package be sealed against dust and insects?" (Expect archival tape and a proper backing board.)

- "Do you have experience framing delicate works on paper, specifically watercolors?" (Crucial for their understanding of the medium's unique needs.)

- "Can you provide a written estimate and explain each component?" (Transparency is key.)

- "What are your recommendations for handling and displaying the framed artwork?" (A good framer will offer advice beyond the workshop.)

Asking these questions demonstrates your commitment to preservation and helps you gauge the framer's expertise and commitment to archival standards.

Here's a quick comparison of framing glazing options, which I find invaluable when making choices:

Glazing Options: A Comparative Overview

Feature | Standard Glass | Conservation Clear Glass | Museum Glass | Conservation Clear Acrylic | Museum Acrylic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UV Protection | Minimal (40-50%) | Good (97%+) | Excellent (99%+) | Good (97%+) | Excellent (99%+) |

| Reflection | High | Moderate | Very Low (Anti-reflective) | Moderate | Very Low (Anti-reflective) |

| Weight | Heavy | Heavy | Heavy | Light | Light |

| Durability | Brittle, shatters | Brittle, shatters | Brittle, shatters | Shatter-resistant, scratches | Shatter-resistant, scratches |

| Cost | Low | Moderate | High | Moderate | High |

| Static | Low | Low | Low | High | High |

| Best Use | Temporary, non-valuable art | Valued art, budget-conscious | High-value art, optimal viewing | Large art, safety, valued art | Large, high-value art, optimal viewing |

Secure Hanging and Installation: The Final Act of Protection

Even the most perfectly framed watercolor needs to be securely hung. Use appropriate hardware for your wall type – whether it's picture wire and hooks into studs, or robust wall anchors for drywall. For larger or more valuable pieces, consider using two hooks for extra stability, a French cleat system for even weight distribution, or even specialized security hardware that prevents easy removal and tampering, especially in public spaces or earthquake-prone areas. A fall can cause irreparable damage to both the frame and the artwork, and trust me, you don't want to explain that accident to an insurance company or a conservator. Beyond security, ensure your artwork is hung level and plumb; minor tilting can, over time, cause internal components to shift, or worse, put uneven stress on the hinging, potentially leading to tears or detachment. The method of hanging should be as thoughtful and professional as the framing itself, representing the final act of securing your artwork within its display environment.

2. Displaying Your Masterpiece: Location, Location, Location

Even with the best archival framing, where you hang your watercolor matters immensely. This is where your inner curator and environmental engineer truly shines, constantly seeking that perfect balance that extends its life and vibrancy, effectively creating a bespoke microclimate for your art. Every placement choice is a critical decision for preservation, a proactive step in safeguarding its delicate beauty.

Understanding Light Sources: Natural vs. Artificial

Before we even talk about placement, let's briefly touch on light itself. Understanding the various components of light is crucial for art preservation. Natural sunlight, even indirect, contains a broad spectrum of light, including powerful ultraviolet (UV) rays (UVA, UVB, UVC, though UVC is mostly filtered by Earth's atmosphere). These are the most damaging wavelengths. Artificial light sources, especially modern LEDs, generally emit very little to no UV radiation, making them a much safer option for illuminating art. However, even artificial light can cause damage if it's too intense (high lux levels), if it has a poor Color Rendering Index (CRI) distorting the artwork's true colors, or if it generates excessive heat (as is common with older incandescent or halogen bulbs), which can accelerate the aging of paper and pigments. It's a delicate balance; you want to see the art, but you don't want to cook it or change its appearance. Different artificial light sources have varying spectral outputs and heat generation characteristics: incandescents emit a lot of heat and some UV, halogens are similar but more efficient, fluorescents can emit significant UV if not properly filtered, and LEDs are generally the safest due to minimal UV and heat. For a deeper dive into lighting for art, check out how to choose the right lighting to enhance your abstract art collection.

To give you a better grasp of safe light levels, consider that museums often limit light exposure for sensitive works on paper to around 50 lux (5 foot-candles). This is a very dim light, barely enough to read by. While impractical for a home, it illustrates the extreme caution professionals take. For home display, aiming for indirect ambient light, especially from modern LEDs which are inherently low in UV, is your best bet. Avoid halogen or incandescent bulbs directly over art, as they generate significant heat and UV. The CRI, by the way, tells you how accurately a light source renders colors compared to natural light; a high CRI (90+) is ideal for art, ensuring your piece looks true to its original hues. For more on the intricacies of light and its interaction with art, you might explore the definitive guide to understanding light in art.

- Avoid Direct Sunlight: The Cardinal Rule of Display This is the golden rule, etched in stone. No matter how good your UV glass is, direct, prolonged sunlight is a relentless, unforgiving enemy. It's not a matter of 'if' but 'when' damage will occur. Find a wall that receives consistently indirect light, or if absolutely unavoidable, consider investing in high-quality UV-filtering blinds or curtains that you actually use. East-facing walls might get intense morning sun, west-facing walls afternoon sun – be meticulously mindful of how light shifts throughout the day in your space, seasonally even. It’s not just about direct rays; even bright ambient light can contribute to cumulative exposure over decades, silently diminishing your artwork. I've heard stories of pieces turning utterly monochrome in sun-drenched rooms over just a few years – a heartbreaking fade from vibrant to ghost, an irreversible loss. For highly sensitive or valuable works, consider implementing a rotation schedule, displaying them for limited periods before returning them to dark, archival storage. This allows you to enjoy them without subjecting them to constant light exposure. Think of it as a sabbatical for your art, allowing it to rest and rejuvenate away from the stresses of display. Even UV-filtering window films are only a partial solution; they reduce, but do not eliminate, the threat. They offer a layer of defense, yes, but they aren't a magical shield that allows you to defy the sun entirely. Vigilance and thoughtful placement remain supreme.

Considering Room Dynamics and Placement

Beyond direct light, consider the general dynamics of the room itself. Is it a high-traffic area with constant movement? Does it experience significant vibrations from nearby appliances (e.g., washing machines, dryers), heavy foot traffic (especially in older buildings), or even exterior elements like passing heavy vehicles? These factors, while often overlooked, can contribute to long-term damage through cumulative micro-trauma. For instance, art placed near a frequently used door might experience subtle jolts over time, potentially impacting the frame's integrity, loosening mounting hardware, or causing the artwork to shift within its enclosure, leading to abrasion or tears. Even artworks hung on exterior walls with poor insulation can be susceptible to greater temperature and humidity swings, a subtle form of environmental assault that causes materials to expand and contract, stressing both the artwork and its frame. If you're decorating a space with such considerations, you might find our guide on choosing art for high-traffic areas durability tips useful, as it offers strategies for mitigating these risks. I often think of it as finding the calmest, most stable corner for your art, much like you'd choose a peaceful spot for focused work.

- Steer Clear of Environmental Extremes: The Unseen Perils of Placement This is where common sense meets conservation. Certain rooms are simply hostile environments for delicate paper artworks.

- Bathrooms and Kitchens: The fluctuating humidity and temperature in these rooms are a big no-no. Think of the steam from showers, the heat from cooking, and the aerosols from cleaning products. Steam and cooking grease can cause paper to buckle, matting to warp, and even encourage aggressive mold growth inside the frame. Trust me, you don't want to find a furry patch on your watercolor; it's a conservator's nightmare. Beyond visible mold, constant high humidity can weaken paper fibers, encourage bacterial growth, and even reactivate water-soluble pigments, causing blurring or migration. The chemicals from cleaning products (ammonia, bleach, solvents) can also off-gas and react with paper and pigments over time, causing discoloration or degradation. And that subtle film of cooking grease? It attracts dust and can chemically react with paper over time, creating a sticky, acidic residue that is incredibly difficult to remove without further damaging the artwork. These are truly battlegrounds for paper art, and frankly, your art doesn't belong there. The combination of high moisture and organic particles creates a perfect storm for biological and chemical degradation.

- Vents and Fireplaces: Avoid placing art directly above radiators, heating vents, or active fireplaces. The dry, localized heat can cause the paper to become excessively brittle, prone to cracking, and accelerate pigment degradation. Furthermore, soot and airborne combustion byproducts from fireplaces can cause irreparable staining and deposit acidic particles onto and into the artwork. The issue here isn't just visible damage, but also the rapid temperature fluctuations and potential for insidious chemical residues from combustion, which accelerate the aging process, leaving your paper brittle and susceptible to cracking at the slightest touch. Basically, any place that feels 'unstable' for you likely isn't great for your art either. It's like leaving a delicate plant in a fluctuating oven; it won't thrive. Even direct exposure to air conditioning vents can cause localized drying and fluctuations that stress the paper, potentially causing uneven shrinkage or expansion.

- Stable Temperatures and Humidity: The Ideal Climate Ideally, aim for a stable relative humidity (RH) between 40-60% and temperatures between 60-75°F (15-24°C). This is the sweet spot for paper and pigments. Drastic fluctuations in either temperature or humidity are far more damaging than a consistent, slightly imperfect environment, as they cause materials to constantly expand and contract, leading to stress and eventual damage. I personally use a simple hygrometer (a device that measures humidity) and a thermometer in my studio and storage areas. Better yet, consider a thermohygrometer or a data logger, which can track conditions over time, giving you a comprehensive understanding of your environment. For larger, more valuable collections, or in environments with extreme external climate swings, investing in a professional HVAC system with integrated climate control (humidifiers/dehumidifiers, precise temperature regulation) might be a necessary, albeit significant, investment. It's a small investment in monitoring that gives me peace of mind and allows me to react if conditions start to drift too far out of ideal ranges. Knowing is half the battle, right? For comprehensive solutions to maintaining these conditions, especially for larger collections, you might want to look into art storage solutions for collectors. Consistent, gentle conditions are your art's best friend. Think of it as creating a permanent spring day for your artwork, without the pollen.

3. Storing Unframed or Collection Pieces: The Hidden Sanctuary

Not all your watercolors will be on display all the time, especially if you're an artist or a serious collector. Proper storage for unframed pieces or rotating collections is just as vital as display care, if not more so. This is where your long-term commitment to preservation truly shines, safeguarding those pieces awaiting their moment in the spotlight, or simply being held in reserve, like precious artifacts in a personal vault. It’s an act of faith in the future, ensuring that the vibrancy you cherish today will be there tomorrow, and for generations to come.

- Archival Storage Boxes and Portfolios: Invest in flat, acid-free archival boxes or portfolios. These are designed to protect your art from dust, light, and environmental pollutants, creating a stable micro-environment. I prefer sturdy clamshell boxes for their rigidity, ease of access, and superior protection. Drop-front boxes are also excellent for allowing easy retrieval without excessive handling. For larger collections or very large individual pieces, you might consider flat file cabinets with acid-free drawers (often metal with a powder-coat finish to prevent off-gassing) or specialized solander boxes which offer exceptional protection and are often custom-made to exacting museum standards. The goal is always to create a dark, stable, and protected enclosure for each piece, shielding it from external contaminants and physical damage. This physical barrier is your first line of defense against both environmental and human-induced harm. For exceptionally large, unframed watercolors that cannot be stored flat, consult a professional conservator about specialized archival tubes with inert liners. These are a last resort and require expert advice to ensure no damage occurs during rolling or unrolling, as this can stress paper and pigment layers.

Types of Archival Storage Boxes

Box Type | Description | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clamshell Box | Hinged lid, opens like a book, rigid. | Excellent protection, easy access, stackable. | Can be bulky for very large quantities. |

| Drop-Front Box | One side drops down for easy removal of contents. | Minimizes handling of artwork, good for stacks. | Requires more horizontal space to open fully. |

| Flat File Cabinet | Metal or archival wood cabinet with shallow drawers. | Maximum protection, secure, excellent for large collections. | Expensive, takes up significant space, heavy. |

| Solander Box | Book-like box with a drop-spine, very rigid, often custom-made. | Supreme protection, elegant presentation, highly durable. | Very expensive, often made to order, heavy. |

| Portfolio Case | Carrying case, often with handles, made from archival board or polypropylene. | Portable, good for transporting, protects against light. | Less rigid than boxes, not ideal for long-term stacking. |

All types should be made from acid-free and lignin-free materials.

- Individual Sleeves/Interleaving: A Personal Space for Each Artwork Each artwork should be separated by a sheet of acid-free tissue paper or stored in an individual Mylar sleeve. This prevents abrasion, pigment transfer between pieces, and provides a crucial barrier against airborne pollutants. Think of it as giving each artwork its own little bed, a personal protective bubble. When using Mylar sleeves (also known as polyester film), ensure they are made from inert polyester (specifically archival grade polyester film like DuPont Mylar D or equivalent) and are open on at least two sides to allow for air circulation and easy removal without touching the artwork surface. This open-sided design helps prevent 'sweating' and allows the artwork to breathe. Glassine paper, another archival option, is excellent for interleaving, providing a smooth, translucent, and pH-neutral barrier, particularly good for preventing smudging of delicate charcoal or graphite details, as well as the subtle surface of watercolors. Always use materials that are specifically labeled 'archival quality' to avoid introducing new contaminants. No shortcuts here; cheap materials will cost you more in the long run.

Archival Interleaving Materials

Material Type | Characteristics | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Acid-Free Tissue | Thin, translucent, pH neutral, available in various weights. | General interleaving, cushioning, wrapping. |

| Mylar (Polyester) | Clear, stable, inert, rigid, non-porous. | Individual sleeves, encapsulation, visible protection. |

| Glassine Paper | Smooth, translucent, pH neutral, water-resistant. | Preventing smudging, separating delicate surfaces. |

| Archival Paper | Thicker, opaque, acid-free, buffered options available. | Backing boards within boxes, separating heavier prints. |

Always ensure the material is specifically labeled as 'archival' or 'conservation grade' to avoid introducing acidity or other harmful chemicals to your artwork.

- Flat Storage is Key: Always, always store watercolors flat. Rolling or folding them can cause permanent creases, cracks in the paper and pigment layer, and irreparable damage to the structural integrity of the artwork. If you have extremely large pieces that cannot be stored flat, consult a conservator about appropriate, very large archival tubes with inner liners, but this should be a last resort and undertaken only with professional guidance. For most works, flat is the golden rule; it respects the inherent structure of the paper and pigment. Gravity is not your friend when it comes to rolled or folded paper.

- Climate-Controlled Space: The Ideal Environment for Long-Term Storage Store your archival boxes in a stable, climate-controlled environment – away from attics, basements, or garages where temperature and humidity can swing wildly and invite pests. A closet inside your main living space, away from exterior walls, is often a surprisingly good, stable choice. This advice aligns with general art storage solutions for collectors. To be truly diligent, consider placing a data logger in your storage area. These devices record temperature and relative humidity over time, giving you a detailed history of your storage environment. This data can be invaluable for pinpointing problematic fluctuations you might not notice day-to-day, allowing for proactive adjustments before damage occurs. It's like having a silent, ever-vigilant sentry watching over your precious collection.

Routine Inspection and Pest Management

Out of sight, out of mind can be dangerous when it comes to stored art. I make it a habit to periodically (every 6-12 months) inspect my stored pieces, even if they're well-protected. Look meticulously for any signs of mold (a powdery or fuzzy growth, often with a musty smell), insect activity (tiny droppings, chewed edges, webbing, or actual insects like silverfish or carpet beetles), or subtle changes in the paper itself (discoloration, embrittlement, foxing). Ensure your storage area is impeccably clean, dry, and free of food debris or organic materials that could attract pests. Implementing an Integrated Pest Management (IPM) strategy, even at home, means being proactive about cleanliness, monitoring (e.g., using sticky traps to identify pests early), and eliminating potential entry points. This might involve sealing cracks, regular vacuuming, and ensuring proper ventilation. A little vigilance goes a long, long way in preventing a catastrophic discovery. And remember, prevention is always easier (and cheaper) than remediation.

The Human Touch: Handling Your Watercolors with Respect

Even the simplest acts of handling can cause damage if not done carefully. This is where mindfulness becomes your greatest tool for preservation, a conscious effort to safeguard delicate beauty.

- Clean Hands & Gloves: The First Line of Contact Protection Always wash your hands thoroughly with soap and water before touching any artwork, ensuring they are completely dry. The natural oils, dirt, and lotions on your hands can transfer invisibly to the paper, leaving behind unsightly and potentially damaging marks that attract pollutants and degrade over time. Think of it as leaving a permanent fingerprint, literally. For an even higher level of protection, especially when dealing with very sensitive or unframed pieces, wear clean, white cotton gloves or nitrile gloves. These create a crucial barrier, preventing skin oils and dirt from transferring. While cotton gloves are breathable and good for general handling of framed or matted works, nitrile gloves offer a more secure barrier against moisture, some chemicals, and fine dust, and are often preferred by conservators for direct handling of unframed paper or delicate surfaces. The key is cleanliness and barrier; pick the glove that best suits the task and your comfort level, but never skip this step!

- Support and Edges: The Art of Gentle Movement When moving an unframed watercolor, always support it from beneath with a rigid, acid-free board (like a piece of archival foam core or museum board). Handle it only by the very edges or corners, and use both hands if possible. Never touch the painted surface, even with gloves. Seriously, don't. The fragility of the pigment layer means even slight pressure can cause damage, and oils can penetrate through layers of paint. For larger unframed works, two people might be needed, each supporting an edge with rigid boards, moving in a coordinated manner to prevent buckling or creasing. When moving a framed artwork, especially a large one, always lift from the bottom and support the sides, avoiding pressure on the glass. Avoid holding it by the top wire alone, as this puts immense stress on the frame and hanging mechanism. It’s a dance of deliberate care, minimizing any stress on the paper or frame.

- Limit Handling: The Best Hands-Off Policy This is perhaps the simplest yet most effective rule: the less you handle your art, the better. Every touch, every movement, introduces a minuscule risk – of abrasion, creasing, or accidental transfer. It's like a delicate flower; too much fiddling just causes petals to drop prematurely. Plan your movements, ensure a clear, clean workspace, and only handle your art when absolutely necessary. Less contact equals less opportunity for accidental damage. This is particularly true for works on paper, which lack the robust surface of an oil painting on canvas. Plan your movements, ensure a clear workspace, and only handle your art when absolutely necessary.

Safe Transport and Handling Beyond the Studio

Moving a watercolor, whether across the room, across the country, or across continents, introduces new risks that require careful planning and often, specialized knowledge. For unframed pieces, always transport them flat between two rigid, acid-free boards, secured gently with archival tape on the outer edges (never touching the artwork), and then placed in a sturdy archival portfolio or box. Avoid rolling large watercolors unless absolutely necessary, and then only with proper archival tubes (acid-free, lignin-free, and larger in diameter than the rolled artwork to prevent excessive curvature) and careful interleaving with glassine or Mylar to prevent movement. For framed pieces, investing in specialized art-shipping boxes (often custom-built with foam inserts and double-boxing for maximum protection) or engaging professional art handlers and specialized art shippers is paramount. Never rely on just bubble wrap and a prayer – inadequate packing can lead to catastrophic damage from even a tiny bump or shock, causing the frame to shift, the glass to break, or the artwork within to suffer. Exhibiting your work, sending it for appraisal, or lending it to a gallery? Always ensure those handling it are acutely aware of its fragility and committed to following rigorous archival handling protocols. Proper art insurance for transit (often separate from home insurance) is also a non-negotiable step. It's an investment in peace of mind, knowing that if the unthinkable happens, you're covered. Just like you wouldn't trust your rare vintage car to just any mechanic, your valuable art deserves specialist handling during transport. This is not the place to economize. You can find more comprehensive advice on this in our guide to understanding art shipping and installation: a collector's guide to logistics.

Preparing for Exhibition or Loan

When your artwork is destined for a gallery, museum, or even a private collection on loan, the stakes for proper handling and condition reporting escalate significantly. Before any piece leaves your care, meticulously document its condition with high-resolution photographs, noting any existing imperfections (e.g., small tears, abrasions, discolorations, previous repairs). This condition report is a vital, detailed document, protecting both you and the borrowing institution, and should be signed by both parties. Ensure that the receiving institution has established, documented protocols for handling works on paper and that their exhibition environment meets stringent archival standards (light levels, temperature, humidity, security). Don't be afraid to ask for these assurances, including their exhibition plan and environmental data; it's your responsibility as a diligent steward of the art. This level of diligence ensures the artwork returns to you in the same condition it left. Always remember to check their insurance coverage for loaned items as well, for that extra layer of peace of mind. For more on the crucial process of documenting your collection, consider reading photographing artwork for web and print.

When to Call in the Pros: Conservation and Restoration

Sometimes, despite our best efforts, accidents happen, or time simply takes its toll. If your watercolor suffers from significant damage – severe fading, pervasive mold growth, tears, punctures, extensive staining, or even insect damage – do not attempt to fix it yourself. Seriously, don't even think about it. You'll likely make it worse, potentially rendering the damage irreversible or significantly more costly to correct. The adage "first, do no harm" is the guiding principle in conservation, and it applies even more so to the amateur restorer. I've heard horror stories of well-intentioned but disastrous DIY repairs, often involving inappropriate glues, tapes, or chemical cleaners that cause far more harm than good.

Preventive vs. Interventive Conservation

It's important to understand the two main branches of conservation. Preventive conservation focuses on minimizing future deterioration by controlling the environment (light, temperature, humidity), proper handling, and archival storage. It's about proactive measures to stop problems before they start. Interventive conservation, on the other hand, involves direct treatment of an object to arrest active deterioration or reverse past damage. This is what a professional conservator does when a piece is already damaged, but their primary goal remains stabilization and preservation of the original integrity, not merely aesthetic restoration. Both are crucial for the long-term survival of artworks, but prevention is always the first and most cost-effective line of defense.

This is when you call a professional paper conservator. These are highly skilled individuals who specialize in the ethical and scientific preservation and restoration of paper-based artworks. They possess a unique blend of art historical knowledge, chemistry, and meticulous manual dexterity. They have the specialized knowledge, tools, and archival materials to assess the damage and, if possible, ethically reverse or stabilize it without further harm to the original integrity of the piece. They can perform a range of delicate treatments, from surface cleaning to remove ingrained dirt and grime, mending tears with archival Japanese papers and reversible adhesives, to sophisticated stain reduction, pH neutralization (to combat acidity), or mold remediation. It's truly incredible what they can achieve, often bringing a piece back from what looks like irreversible damage, restoring both its aesthetic and historical value. Finding a reputable conservator is an investment in the longevity of your piece, and it's absolutely worth it for valuable, sentimentally important, or historically significant artworks. It’s part of understanding the true value of your art, much like understanding art appraisals for its monetary value. They are the specialists who can truly perform magic, but it’s a magic based on science and ethical practice.

Finding and Vetting a Professional Conservator: Your Art's Medical Specialist

So, how do you find one of these wizards? Start by asking for referrals from reputable art galleries, museums, or even fine art insurance companies. Professional organizations for conservators (like the American Institute for Conservation - AIC in the US, or ICON in the UK) often have online directories of accredited professionals. When you find a potential conservator, don't be shy: conduct thorough due diligence. Ask about their specialization (paper conservation is key, as different mediums require different expertise), their years of experience, specific training, and request to see examples of their previous work on similar pieces. Always ask for a detailed, written treatment proposal that outlines the proposed interventions, the materials to be used (ensuring they are reversible and archival), and a transparent cost estimate. A good conservator will be transparent, ethical, prioritize the long-term stability and integrity of the artwork above all else, and will communicate clearly throughout the process, even providing photographic documentation of 'before' and 'after' treatment. They are partners in your art's long-term health, much like a trusted family doctor, but for your cultural treasures. For more on understanding the value of such expertise, our article on understanding art appraisals: what every collector needs to know can provide further context.

Common Misconceptions in Watercolor Care: Separating Fact from Fiction

There are a few persistent myths floating around about watercolor care that I feel compelled to address. It's easy to assume certain things, but these can sometimes lead to unintentional harm or missed opportunities for optimal preservation.

- Misconception 1: "All glass is the same for framing." Absolutely not! This is one of the most common and damaging myths. As we discussed, standard window glass offers minimal UV protection. You need specialized UV-filtering glazing to truly safeguard against fading and paper degradation. Don't let a framer convince you otherwise if you care about the long-term health and vibrancy of your artwork. It's an investment that pays dividends.

- Misconception 2: "You can just varnish a watercolor like an oil painting." This is a hard NO. Traditional watercolors are not designed to be varnished. Applying a varnish directly can fundamentally alter the delicate, absorbent nature of the pigments, change the paper's texture and color saturation, and often results in an irreversible, glossy finish that utterly detracts from the watercolor's inherent aesthetic. While some contemporary artists experiment with fixatives (typically a thin, sprayable resin solution that offers a minimal protective layer), these are generally not considered archival in the same way framing is, and can still alter the surface appearance or pigment vibrancy over time. The established, archival method for protection remains proper framing behind UV-filtering glazing. You can learn more about appropriate varnishing for other mediums like how to varnish an oil painting a step-by-step guide or how to varnish an acrylic painting.

- Misconception 3: "A dry environment is always best for paper." While high humidity is problematic and a breeding ground for mold, an environment that is too dry can also cause significant issues. Extremely low humidity can desiccate paper fibers, making the paper brittle and stiff, leading to cracking, especially if the paper has been stretched or previously exposed to fluctuating conditions. It can also cause delicate paint layers, particularly if applied thickly or with certain binders, to become brittle and flake off the surface. Stability, not extreme dryness, is the optimal goal for long-term preservation, aiming for that sweet spot of 40-60% relative humidity.

- Misconception 4: "Small tears or stains can be fixed with household tape or cleaners." Oh, please, no! This is perhaps the most dangerous misconception, leading to irreversible damage. Household tapes, even seemingly benign 'scotch tape,' contain adhesives that will degrade over time, yellowing, becoming brittle, and leaving irreversible stains and residues that are incredibly difficult, if not impossible, for a conservator to remove without further damaging the paper. The chemical composition of these adhesives can actively cross-link with paper fibers, creating a permanent, disfiguring bond. And as for household cleaners? They are almost always highly acidic or alkaline, designed to dissolve grime, not to delicately treat fragile paper and pigments. You’ll just end up making a terrible situation far, far worse, often introducing new, insoluble chemical stains or accelerating the paper's degradation. Always, always, call a professional conservator for any damage, no matter how small it seems. This is not a DIY project; it's a specialist repair job, and attempting it yourself is a guaranteed way to devalue and potentially destroy your artwork. Think of it like performing surgery with kitchen utensils; it's just not going to end well.

The Importance of Archival Prints and Digital Reproductions: A Modern Perspective

In our modern world, not every "watercolor" you encounter is an original. High-quality prints and digital reproductions have become incredibly popular, allowing art to be more accessible to a wider audience. But do they require the same meticulous care? The answer is nuanced: yes and no.

Original watercolor paintings are unique, hand-created works, carrying the direct touch and intention of the artist. Their preservation ensures their longevity as singular cultural objects, historical records, and significant investments. Their value lies in their direct connection to the artist's hand and the irreplaceable nature of the original. Archival prints, such as Giclée prints, are high-fidelity reproductions often printed with advanced, pigment-based inks on acid-free, often 100% cotton rag paper. While they are not originals, they are meticulously crafted for longevity and should absolutely still be framed with UV-filtering glass and archival materials to prevent fading and degradation of the print itself. Their value, while distinct from an original, can still be significant, especially for limited editions or those signed by the artist. When considering prints, always look for detailed information on the print process (e.g., inkjet, giclée, offset lithography), ink type (pigment inks are vastly superior to dye-based inks for lightfastness), and paper quality (e.g., alpha-cellulose vs. 100% cotton rag, weight, surface). These factors directly impact the print's own lightfastness and stability. For more on this, check out our article what is giclee print. I always tell people to think of it like this: an original watercolor is a handwritten letter from history, while a giclée print is a meticulously crafted, museum-quality reproduction. Both are valuable, but their inherent nature and care requirements differ subtly.

Original vs. Archival Print Care: A Comparison

Feature | Original Watercolor | Archival Giclée Print | Additional Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uniqueness | One-of-a-kind, irreplaceable. | High-quality reproduction, often limited edition. | Original carries the artist's direct hand and intention. |

| Pigments | Directly applied artist pigments. | Pigment-based archival inks. | Pigment density and binder can differ. |

| Paper | Original artist's paper (varying archival quality). | Certified archival, acid-free paper (e.g., cotton rag). | Print paper is typically chosen for its archival properties. |

| Lightfastness | Varies by artist's pigments, generally high for modern. | High, dependent on ink and paper quality. | Always check specific ratings for both originals and prints. |

| Fragility | Very high, delicate surface, susceptible to all damage. | High, paper susceptible to physical damage, but pigment layer often more robust. | Originals often have more subtle surface textures. |

| Framing | Absolute necessity for display, UV glass, archival mat. | Highly recommended for longevity, UV glass, archival mat. | Extends lifespan and protects against environmental factors. |

| Handling | Minimal, gloves, rigid support. | Careful, gloves recommended for valuable prints. | Avoid touching surfaces to prevent oil transfer and smudges. |

| Conservation | May require specialist intervention for damage. | Less likely, but paper conservator for significant damage. | Professional intervention for originals is highly specialized. |

| Value Driver | Artist's hand, historical significance, rarity. | Edition size, artist's signature, print quality. | Provenance and condition are key for both. |

| Print Technology | N/A | Inkjet (Giclée), pigment-based. | Different print methods have varying archival qualities. |

| Surface Durability | Very delicate, water-soluble. | Generally more resistant to minor abrasion than original watercolor pigment layers. | Still avoid direct contact. |

Digital reproductions, on the other hand, present a whole different set of considerations, focusing more on screen quality, color calibration, and appropriate lighting conditions for viewing rather than physical preservation. While digital files offer immense flexibility for sharing and display, they are not a substitute for the archival preservation of physical artworks. They have their own vulnerabilities, primarily related to technological obsolescence (file formats becoming unreadable), data corruption (bit rot), and the fragility of storage media, a quiet but persistent threat in our digital age. Even discussions around NFTs and blockchain for digital art, while interesting and offering new avenues for provenance and ownership in the digital realm, don't fundamentally change the physical preservation needs of tangible artworks; they address a different set of challenges entirely. I always emphasize that a digital file, no matter how high-resolution, is a copy, not the irreplaceable original – and its long-term viability is intrinsically tied to evolving technology, not the inherent stability of archival materials. Therefore, they demand a different kind of 'preservation' through consistent data migration and backup strategies.

Frequently Asked Questions About Watercolor Care

Here are some of the questions I often get asked, distilled for clarity and practical advice.

Q: Can I hang my watercolor in a sunroom if it has UV glass?

A: I really wouldn't recommend it. While UV glass is excellent, it doesn't block 100% of UV rays, and the intensity and duration of direct sunlight in a sunroom will still cause accelerated fading over time. Indirect light is always the safest bet. Think of UV glass as a fantastic sunscreen, but you still wouldn't sit directly in the blazing sun for hours on end without consequences, would you? Cumulative exposure is the enemy, and even with 99% UV blocking, that remaining 1% over years in intense sunlight adds up to irreversible damage.

Q: Should I rotate my watercolors off display?

A: For highly sensitive or valuable watercolors, absolutely. Implementing a rotation schedule is an excellent preventive conservation strategy. Displaying a piece for a few months to a year, then returning it to dark, archival storage for an equal or longer period, significantly reduces its cumulative light exposure and extends its lifespan. It's like giving your artwork a much-needed sabbatical from the stresses of being on display.

Q: How do I clean the glass on my framed watercolor?

A: Use a soft, lint-free cloth and a very small amount of ammonia-free glass cleaner (or just distilled water). Crucially, spray the cleaner onto the cloth, not directly onto the glass. This prevents liquid from seeping under the frame and damaging the artwork or matting. Gently wipe. For acrylic, use a cleaner specifically designed for acrylic, as some glass cleaners can damage its surface or cause hazing.

Q: My watercolor paper is wavy or buckled. Can I flatten it myself?

A: If it's framed and buckled, it likely needs to be re-framed with proper archival techniques (like a well-fitted mat and backing that allows for expansion). The buckling is often a sign that the paper is reacting to environmental moisture and doesn't have room to expand and contract. If it's unframed, gentle humidification and pressing by a professional conservator might be possible, but attempting this yourself can cause irreparable damage, reactivate pigments, or even introduce mold. So, my advice is firm: don't try this at home. Leave it to the experts. The risk of irreversible damage far outweighs any perceived saving.

Q: Are modern watercolor paints more lightfast than older ones?

A: Generally, yes! Paint manufacturers have made significant advancements in pigment technology, leading to far more stable and durable paints. Many professional-grade modern watercolors are highly lightfast. Always check the pigment lightfastness ratings (often indicated by ASTM ratings I, II, or stars on the paint tube/pan) when purchasing paints if longevity is a concern. This is something I always consider when reviewing professional watercolor sets and is a critical factor for artists and collectors alike.

Q: Is it okay to display watercolors in a brightly lit room with artificial light?

A: Yes, generally artificial light (especially modern LED lights with low UV output) is much safer than natural sunlight. The key is to avoid placing art directly under very strong, hot spotlights which could generate heat and affect the paper and pigments. Ambient room lighting is usually perfectly fine, and even targeted art lighting can be used safely if it's LED, low heat, and correctly positioned. The absence of UV in most modern artificial light sources makes a huge difference.

Q: How often should I re-frame my watercolor painting?

A: If your watercolor was framed using professional archival materials and techniques, it might not need re-framing for decades, unless there's visible damage, degradation of materials, or a desire to change the aesthetic. However, if if it's an older piece, or if you suspect non-archival materials were used (common in frames from before the 1980s), an inspection every 5-10 years by a professional framer is a good idea. They can assess the condition of the materials and advise if an upgrade is necessary. Ignoring potential issues can lead to irreversible damage, often silently.

Q: Can I store my collection in an unheated attic or damp basement?

A: A resounding no! Attics, basements, and garages are almost universally unsuitable for storing any artwork, especially delicate watercolors. These spaces are prone to extreme fluctuations in temperature and humidity, which cause paper to expand, contract, buckle, and become brittle. They are also breeding grounds for pests, mold, and dust. Always opt for a stable, climate-controlled interior living space for long-term storage, as detailed in the "Storing Unframed or Collection Pieces" section.

Q: Can I use a regular cleaning wipe on my framed art glass/acrylic?

A: No, absolutely not. Many household cleaning wipes contain chemicals that can etch, haze, or leave residues on both glass and acrylic, and these chemicals could potentially off-gas into the frame package. Always use a dedicated, gentle cleaner as described above, or simply a damp cloth with distilled water, followed by a dry, lint-free cloth.

Conclusion: Guardians of the Delicate Beauty for Generations to Come

Caring for watercolor paintings might seem like a lot of rules, a daunting list of dos and don'ts, but really, it boils down to understanding their inherent delicacy and giving them the profound respect they deserve. These artworks, with their ethereal washes, luminous colors, and unique artistic expressions, bring so much joy and beauty into our lives. They are fragile whispers of creativity, demanding our stewardship, a quiet dedication to their enduring presence.

By taking simple, informed, and consistent steps in their archival framing, thoughtful display, and strategic storage, you transcend the role of mere owner; you become a true guardian of that beauty. You are actively ensuring that your treasured pieces can continue to inspire and delight for not just years, but for generations to come. It’s a relatively small, ongoing effort for a lifetime—and beyond—of vibrant, lasting art. It's about preserving a piece of the artist's soul, a slice of human creativity, and a legacy for future admirers. So, take these lessons to heart, become the vigilant steward your watercolors deserve, and enjoy their enduring luminosity. And if you're ever looking for new, vibrant pieces to add to your collection, remember that investing in art is also investing in beauty that lasts – you know where to buy original contemporary art! Or delve deeper into the artist's journey at Zen Museum or explore their creative evolution through their timeline. May your watercolors remain as luminous and captivating as the day they were created, a testament to thoughtful preservation and deep appreciation. The longevity of art lies in the hands of its guardians.