Art About Guilt: An Artist's Deep Dive into Facing Shadows on Canvas and In Life

Explore how artists, including myself, confront and depict the complex emotion of guilt – personal, societal, historical, and creative – through various mediums and movements, and discover where to find art that resonates with this deeply human experience.

Art About Guilt: Facing the Shadows on Canvas and In Life

Guilt. It's that heavy, sticky feeling that clings to you long after the moment has passed. It whispers 'what if?' or shouts 'you should have!' in the quiet corners of your mind. As an artist, I've often found myself wrestling with it – not just personal guilt (though there's plenty of that, usually involving deadlines or questionable color choices), but the broader, societal, historical, and even creative kind. This article isn't just an academic look; it's a personal journey into how artists, myself included, grapple with guilt in its many forms and how that struggle manifests on canvas and beyond.

Let's be honest, who doesn't carry a little guilt around? Maybe it's about that thing you said years ago, or the opportunity you didn't take, or perhaps something much heavier, a weight you feel from history or the world around you. It's a universal thread, and because art is fundamentally about the human condition, it's no surprise that artists have been exploring this uncomfortable emotion for centuries. It's not always obvious, like a painting titled 'The Weight of My Regrets' (though I'm sure that exists somewhere). Often, art about guilt is subtle, woven into the fabric of a piece, hiding in the shadows or screaming from the canvas in abstract form. Even way back, artists were depicting scenes of moral failing and its consequences, showing that this uncomfortable emotion has long been part of the human story told through art.

Feeling a connection to art that explores deep emotions? You might find something that resonates in my collection for sale.

Why Artists Turn Towards the Uncomfortable

Why would anyone choose to make art about something as unpleasant as guilt? Honestly, sometimes I wonder that myself when I'm staring at a blank canvas, feeling guilty about not having started yet. Or like that time I spent an entire afternoon meticulously organizing my paint tubes by shade instead of actually painting – the sheer, unproductive guilt was almost paralyzing. But the truth is, art thrives on emotion, on the messy, complicated stuff of life. And guilt? It's a powerhouse emotion, a quiet internal storm that artists, bless their complicated souls, often feel compelled to translate.

Artists are often observers, processors, and translators of the human condition. We see the world, we feel it, and we try to make sense of it, or at least express the feeling of not making sense of it. Guilt, whether personal or collective, is a fundamental part of that condition. It shapes our actions, our relationships, and our internal landscapes. It can stem from a million places: personal mistakes, perceived failures, things left unsaid or undone, or even the weight of history and societal wrongs. It's a way to externalize it, to understand it, maybe even to share the burden or provoke empathy in others. It's like saying, "Hey, you feel this too? Let's look at it together, even if it's uncomfortable." What kind of internal storms do you find yourself grappling with? Sometimes just acknowledging them is the first step, whether in life or in art.

A Historical Weight: Guilt Through the Ages in Art

Art's engagement with guilt isn't new; it's woven into the very fabric of art history. Even in Ancient and Classical art, while overt depictions of personal guilt might be less common than in later periods, themes of transgression, divine retribution, fate, and the consequences of human hubris were explored in mythology, drama, and the visual arts that illustrated these narratives. Think of depictions of figures from Greek tragedies grappling with the aftermath of their actions, or Roman reliefs showing the consequences of defying authority. These works laid groundwork for exploring moral and societal burdens.

In Medieval art, depictions of sin, judgment, and repentance were central, often serving didactic purposes to guide viewers towards moral behavior and away from eternal damnation. Think of dramatic altarpieces or illuminated manuscripts illustrating the consequences of moral failings, like scenes from the Last Judgment or vivid portrayals of the Seven Deadly Sins and their punishments. The focus was often on religious or moral guilt, a collective understanding of right and wrong dictated by faith.

Moving into the Renaissance, while religious themes persisted, there was a growing focus on the individual. Artists began to explore the inner turmoil and conscience of figures. Scenes like Adam and Eve after the Fall, their faces etched with shame and regret, became powerful explorations of personal guilt and its impact. Consider Masaccio's The Expulsion from the Garden of Eden, where the raw anguish and shame of Adam and Eve are palpable. But even in portraits or genre scenes, subtle cues could hint at inner states. Consider a portrait where the subject's gaze is averted, or their hands are clasped tightly – these small details, when interpreted through body language in art, can suggest unease, regret, or a burdened conscience. Peter von Cornelius's "The Israelites Resting" might not be explicitly about guilt, but the weariness and weight conveyed by the figures' postures and expressions can certainly resonate with the burden of past actions or difficult journeys.

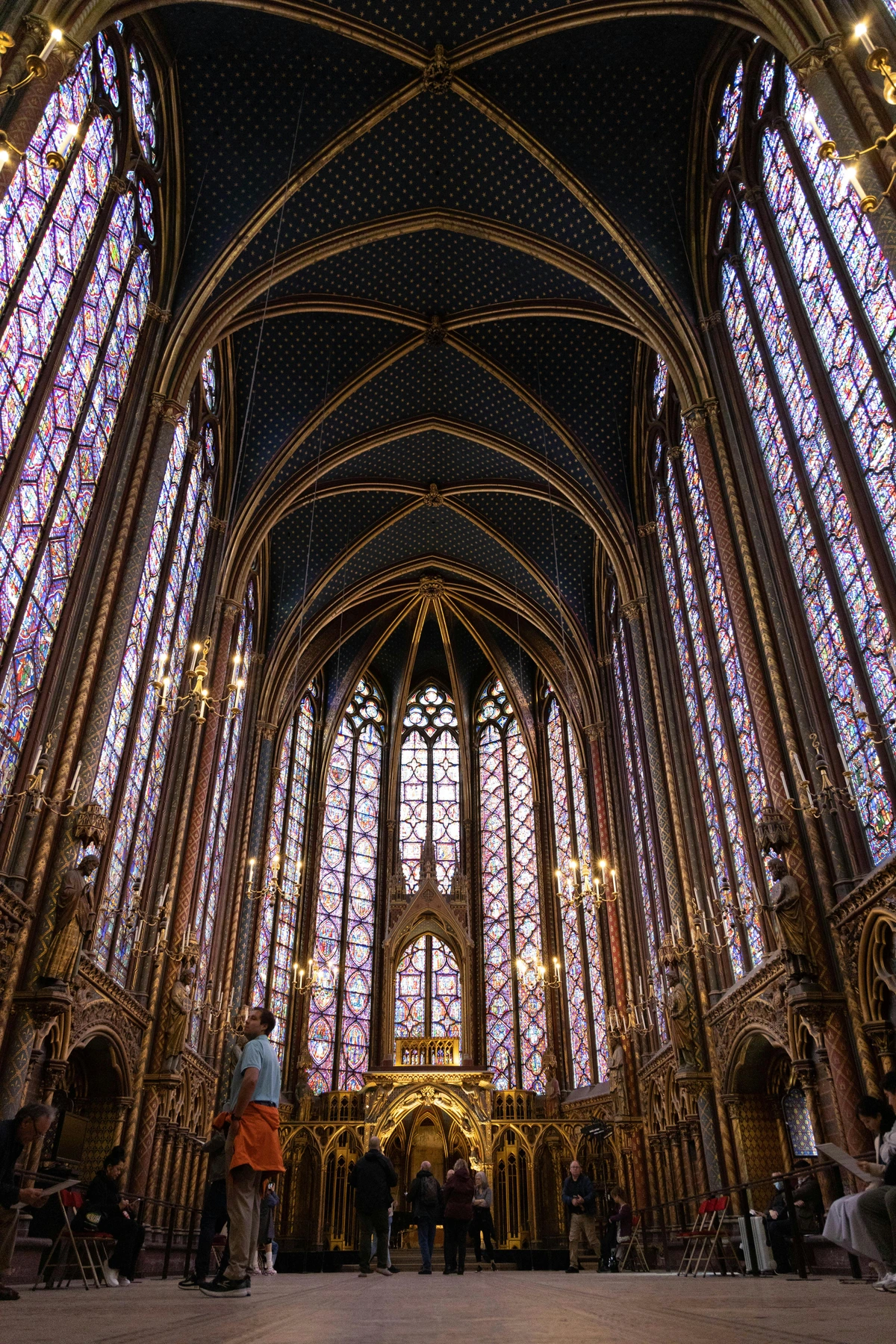

![]()

The Baroque era often amplified this drama, using intense light and shadow (how artists use light and shadow dramatically) and dynamic compositions to depict emotional intensity, including the agony of guilt or the fervor of repentance. Think of Caravaggio's dramatic depictions of biblical scenes where figures grapple with moral choices and their consequences. A powerful example is Caravaggio's The Denial of Saint Peter, which captures the raw, immediate anguish and regret of Peter after denying Christ, using stark chiaroscuro to heighten the emotional turmoil. Other Baroque artists like Rembrandt also explored inner psychological states, sometimes depicting figures in moments of deep contemplation or remorse. Later periods, like the Victorian era, saw guilt explored through narrative painting and literature, often focusing on social transgressions and their psychological toll, sometimes with a moralizing tone.

As we move towards Romanticism, the focus shifts further inward. Artists explored intense emotions, melancholy, and the sublime, often touching upon themes of loss, regret, and the weight of history or personal failings. Think of dramatic landscapes or scenes depicting solitary figures burdened by unseen forces. Caspar David Friedrich's solitary figures contemplating vast, often somber landscapes can evoke a sense of existential weight that resonates with feelings of regret or a burdened conscience. Théodore Géricault's The Raft of the Medusa, while a depiction of survival, is steeped in the political and moral fallout of a disaster caused by negligence, implicitly raising questions of guilt and responsibility.

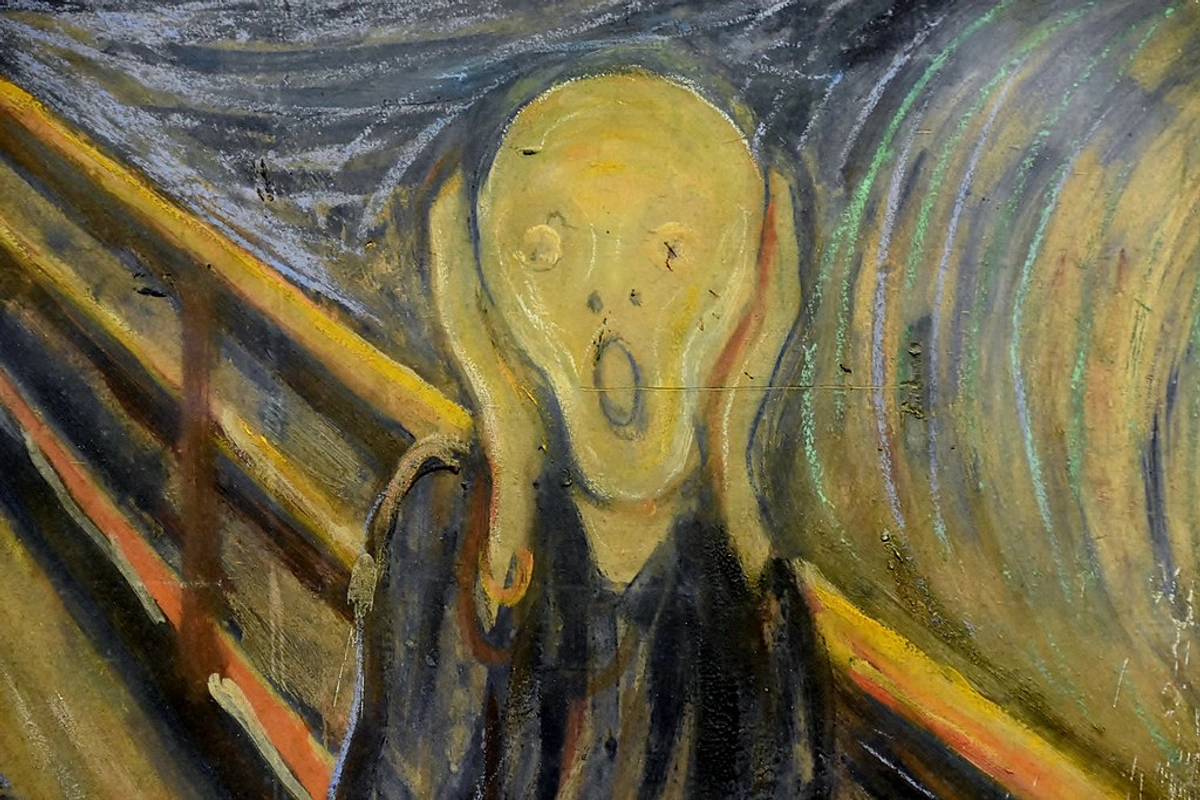

Symbolism delved even deeper into the subconscious and inner psychological states. Artists used symbolic imagery to evoke complex emotions and ideas that were difficult to express directly. Guilt, anxiety, and the darker aspects of the psyche were fertile ground for Symbolist artists, who sought to represent the unseen world of feeling and thought. Edvard Munch, often associated with Expressionism but with roots in Symbolism, famously captured states of anxiety and despair that are closely linked to guilt.

This historical journey shows that while the form and focus of depicting guilt have changed, the underlying human experience remains a constant source of artistic inspiration (or perhaps, compulsion). The shift from collective religious guilt to individual psychological turmoil reflects broader societal changes, but the artistic impulse to explore this difficult emotion endures.

How Guilt Manifests in Art: Beyond the Obvious

So, how do artists actually do it? How do they take this internal feeling and make it visible? It's a fascinating question, and the answers are as varied as the types of artwork explained out there. Artists employ a vast toolkit of techniques and approaches to capture the nuances of guilt.

Narrative and Figurative Depictions

Sometimes, it's quite direct. Historical or religious paintings often depict scenes of sin, judgment, or repentance, directly engaging with the concept of moral guilt. Think of classic depictions like Adam and Eve after the Fall, their faces etched with shame and regret, or scenes of penitent saints like Mary Magdalene. These works use recognizable stories and human forms to convey the weight of guilt.

More modern figurative work might show figures burdened, hiding their faces, isolated, or physically contorted. Body language is a powerful tool here, conveying unspoken emotional states. Learning how to interpret these visual cues can unlock layers of meaning, including unspoken guilt or shame.

It's worth pausing here to consider the distinction between guilt and shame, as art often explores the blurry lines between them. Guilt is typically associated with a specific action or inaction – the feeling that you did something wrong. Shame, on the other hand, is a more pervasive feeling about one's self – the belief that you are wrong or fundamentally flawed. Art can depict this difference: a painting showing a figure confessing a specific sin might focus on guilt, while a figure hiding their face or physically shrinking might convey shame. Artists like Jenny Saville or Francis Bacon, while not exclusively focused on guilt, often depict the human form in ways that convey deep psychological distress, vulnerability, or the weight of existence, which can resonate strongly with feelings of guilt or shame. Their distorted or raw portrayals can feel like the physical manifestation of internal turmoil. Artists like Adrian Ghenie, known for his distorted portraits, can evoke a sense of unease and psychological burden that might touch upon themes of difficult history or internal conflict.

Abstract and Symbolic Expressions

This is where things get really interesting for me, as someone who often works abstractly. Guilt doesn't have a single look. It can feel like a heavy weight, a sharp pain, a suffocating cloud, or a tangled mess. Abstract artists can use color, form, and texture to evoke these feelings.

Dark, muddy colors, sharp, jagged shapes, or dense, claustrophobic compositions can all suggest the emotional landscape of guilt. Conversely, sometimes a stark, empty space or the deliberate use of negative space can convey the isolation, void, or sense of absence left by guilt or regret. The way artists use color or manipulate art elements can speak volumes without depicting anything literal. For instance, a tangled knot of dark lines might visually represent the feeling of being trapped by regret, or a heavy block of oppressive color could feel like the weight of a past mistake. It's important to remember that these interpretations are subjective, drawing on universal associations but filtered through personal experience.

Specific abstract techniques can also mirror the experience of guilt. Layering paint or materials can suggest hidden truths or buried feelings. Distressed surfaces, tearing, or fragmentation might evoke a sense of being broken or damaged by past actions. Repetitive marks could reflect the obsessive replaying of events in one's mind.

Expressionism, for example, is a movement deeply concerned with internal emotional states. Artists like Edvard Munch, famous for "The Scream," weren't just painting what they saw, but what they felt. While "The Scream" is often interpreted as anxiety, that raw, exposed anguish is closely related to the overwhelming dread and torment guilt can bring. The swirling, distorted landscape and the figure's contorted face viscerally communicate a feeling of being overwhelmed by internal turmoil, a state often intertwined with profound guilt. You can dive deeper into this movement in my ultimate guide to Expressionism.

Other abstract artists also tap into these deep emotional wells. Mark Rothko's large color fields, while often discussed in terms of the sublime or spiritual, can also evoke feelings of melancholy, introspection, or even a somber weight that resonates with the experience of guilt. The sheer scale and immersive nature of his large canvases can feel overwhelming, mirroring the way guilt can consume one's internal space. Contemporary abstract artists like Anselm Kiefer (discussed below for his materials) or even some works by Cy Twombly with their layered, frantic marks can evoke a sense of historical burden or internal struggle that touches upon themes of guilt or trauma.

Materials and Process as Metaphor

Sometimes, the very materials an artist chooses or the process they employ can carry the weight of guilt or difficult history. Anselm Kiefer, whose work often confronts Germany's difficult past, uses heavy materials like lead, straw, and ash. These materials are not just inert substances; they carry historical resonance and physical weight, speaking to burden, decay, and consequence. The rough, layered textures and often damaged surfaces in his work can evoke a sense of historical trauma and collective guilt. Similarly, an artist might use repetitive, painstaking, or even destructive processes (like burning, cutting, or layering) that mirror the internal experience of grappling with guilt – the constant replaying of events, the feeling of being damaged, or the attempt to build something new from difficult remnants. Consider the work of Doris Salcedo, who uses everyday objects like chairs or clothing, often altered or embedded in architectural spaces, to speak to themes of violence, absence, and mourning, which can certainly evoke feelings of collective trauma and unresolved history.

Art as Confession, Commentary, or Confrontation

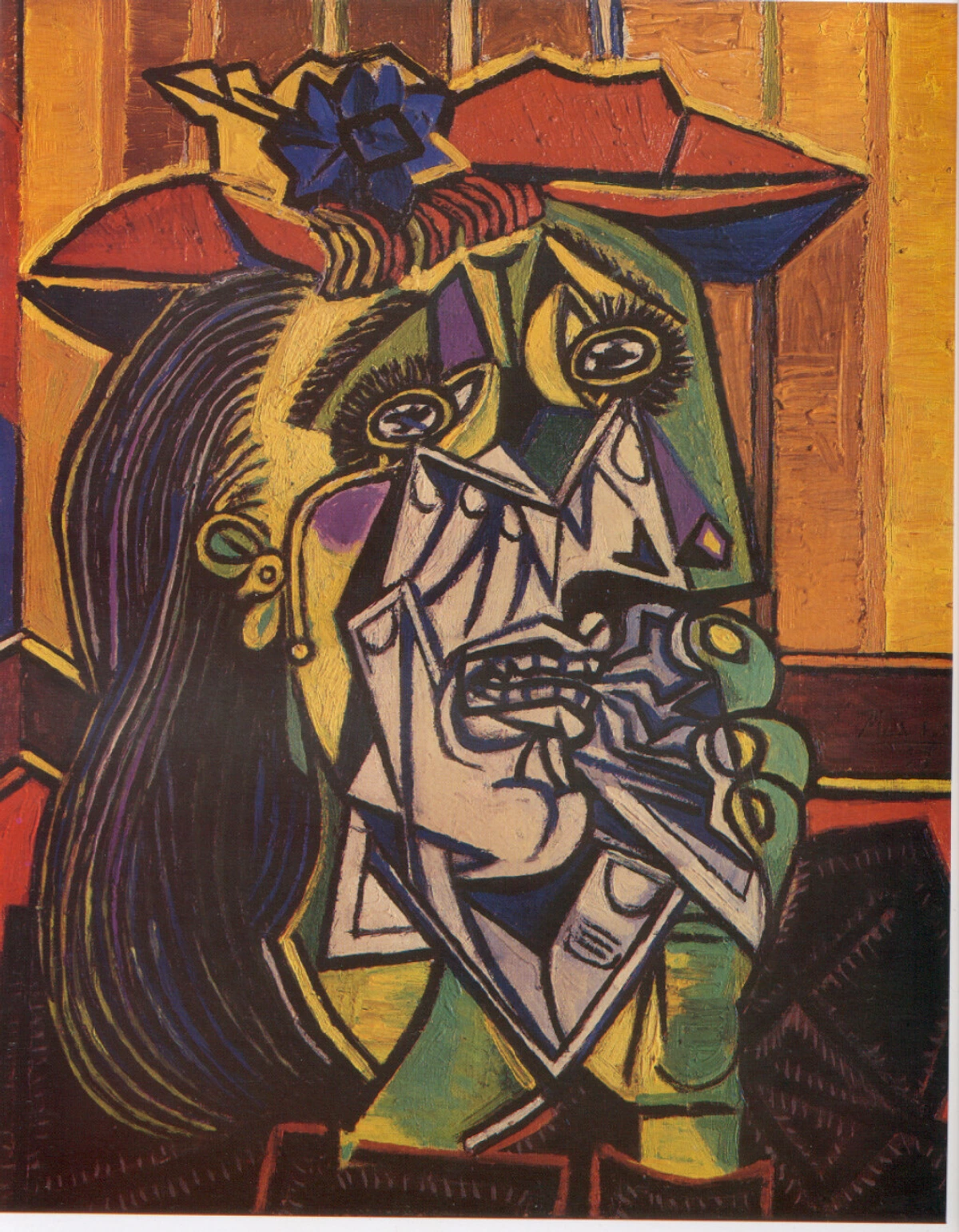

Some artists use their work as a form of public confession or as commentary on collective guilt. This can be seen powerfully in protest art, where artists confront societal injustices and the collective responsibility (and thus, potential guilt) of a community or nation. Picasso's "Guernica," for instance, while a direct response to the bombing of a town, serves as a powerful indictment of the perpetrators and evokes a sense of shared human suffering and the guilt of inaction or complicity. It's a monumental cry against violence that forces viewers to confront the horror and their own potential connection to systems that allow such atrocities.

Beyond specific historical events, artists also address broader themes of collective guilt related to colonialism, environmental destruction, or social inequality. Works that highlight the consequences of these issues can implicitly or explicitly challenge the viewer to confront their own position or complicity within these systems. Artists like Kara Walker, who uses silhouette cutouts to explore themes of race, gender, and violence in the American South, often provoke discomfort and force viewers to confront difficult historical truths and their lingering impact, which can certainly stir feelings related to collective guilt. Sometimes, artists might use irony or satire to highlight hypocrisy or societal blind spots related to guilt, forcing a confrontation through uncomfortable humor. Think of the biting social commentary in the works of artists like Francisco Goya, whose Caprichos series used dark, satirical imagery to expose the follies and vices of Spanish society, implicitly pointing to a collective moral failing.

Performance art can also be a powerful medium for exploring guilt, often by creating uncomfortable situations for the audience that mirror feelings of complicity or unease. An artist might perform an action that highlights a societal blind spot or historical injustice, forcing the viewer to confront their own potential role or passive acceptance, thereby triggering a sense of discomfort akin to guilt. Marina Abramović's work, while exploring many themes, often involves endurance and vulnerability that can provoke introspection and a sense of shared human frailty, sometimes touching on the discomfort of witnessing suffering or inaction. A more direct example might be a performance piece where an artist physically carries a heavy burden, symbolizing collective historical weight, or engages in repetitive, seemingly pointless tasks that evoke the feeling of being trapped by past mistakes.

Installation art can create immersive environments that evoke feelings of being trapped, burdened, or overwhelmed, mirroring the psychological experience of guilt. Think of rooms filled with oppressive objects or spaces designed to feel disorienting or heavy. These environments can make the viewer physically feel the weight of a concept like collective guilt or historical trauma. An installation might use sound, light, and physical barriers to create a sense of confinement or unease, prompting reflection on themes of responsibility or consequence.

Even photography can capture moments of profound guilt or its aftermath, whether through documentary images of suffering that provoke viewer guilt or staged portraits that explore the subject's internal state. The choice of medium itself can add layers – the starkness of black and white photography, the raw immediacy of performance, the immersive quality of installation.

Other forms like video art or sound art can also delve into guilt through narrative, abstract soundscapes, or unsettling visuals that evoke psychological states. A video piece might use fragmented imagery and disjointed sound to mirror the fractured experience of regret, while sound art could employ dissonant tones or repetitive loops to create a sense of unease or being trapped by thought. Even literary art, when integrated into visual pieces or installations, can directly convey narratives or internal monologues related to guilt.

My Own Dance with Guilt (and the Studio)

Okay, confession time. My personal guilt rarely manifests as grand historical narratives on canvas. It's usually more mundane, more... studio-adjacent. Like the guilt of having a studio full of supplies I haven't touched in a week because I got distracted by, I don't know, reorganizing my sock drawer. Or the guilt of feeling like I should be making profound, world-changing art when all I want to do is play with color combinations or experiment with textures.

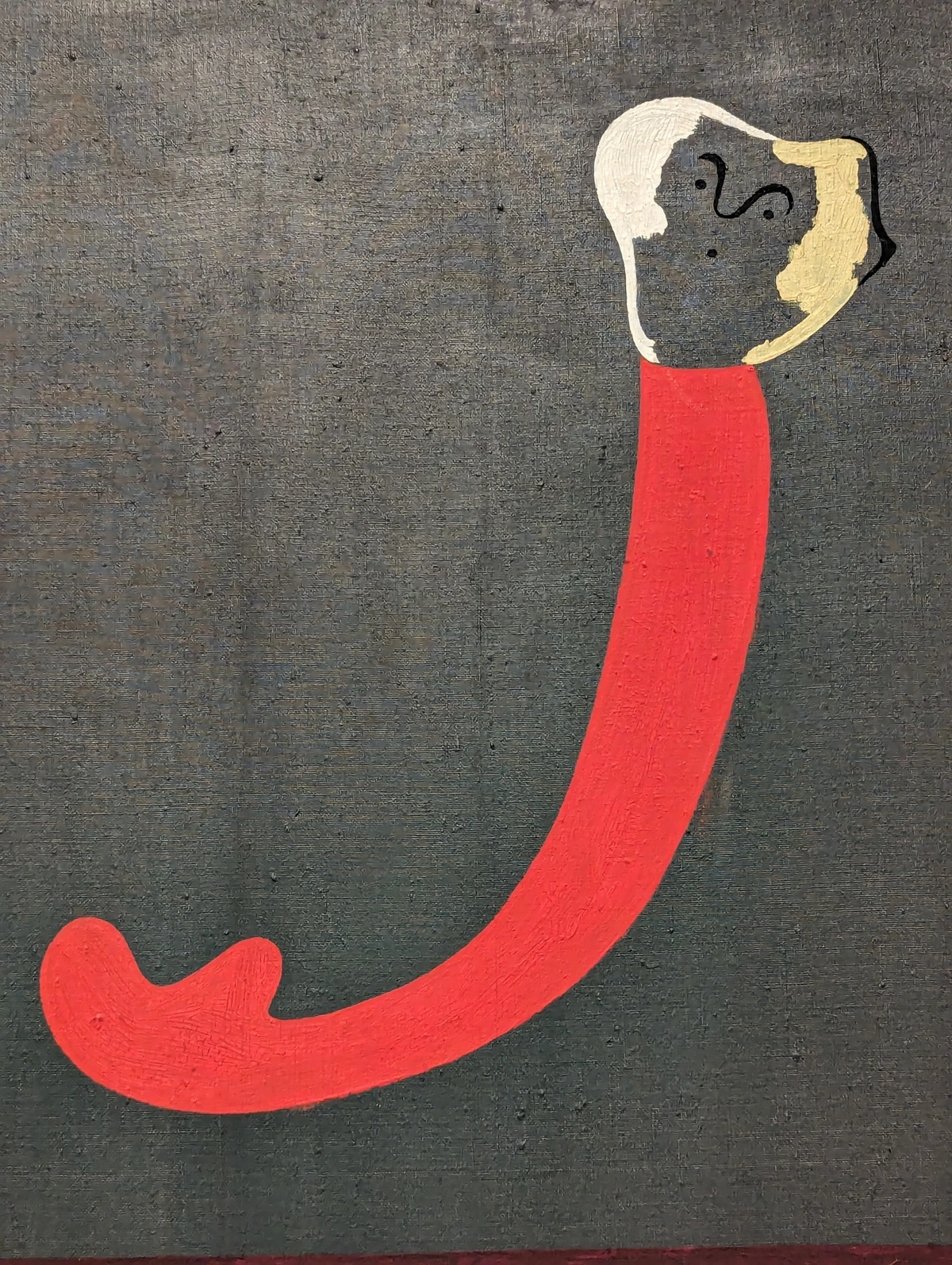

There's the guilt of comparing myself to other artists, feeling inadequate because my output isn't as prolific or my themes aren't as 'serious'. And then there's the classic artist guilt: starting a piece with grand intentions and abandoning it halfway through, leaving it to stare accusingly from the corner of the studio. It's a constant, low-level hum of 'could do better', 'should be doing more'. This feeling of inadequacy or the weight of unfinished projects? It definitely influences my abstract work sometimes. That dense, layered texture in a recent piece? Maybe it wasn't just about exploring texture; maybe it was the visual manifestation of feeling buried under a pile of 'shoulds'. Or the sharp, contrasting colors? Perhaps the internal friction of wanting to create but feeling blocked. For example, I remember starting a large abstract piece with a very clear vision, only to get stuck and abandon it for weeks. The sight of that half-finished canvas in the corner felt like a physical weight, a constant reminder of creative failure. When I finally returned to it, the frustration and guilt manifested in aggressive, layered brushstrokes and a chaotic mix of dark colors that weren't in my original plan. The finished piece, while visually dynamic, carries that undercurrent of struggle and the feeling of having wrestled something difficult into existence. It's like the canvas becomes a silent confessional for my creative shortcomings.

But even these small, silly guilts are part of the creative journey. Sometimes, the frustration or the feeling of inadequacy does push me towards the easel. It becomes a strange kind of fuel. That nagging feeling that I'm wasting time or not living up to my potential can sometimes be the very thing that forces me to pick up a brush. My artist timeline is probably just a series of creative bursts punctuated by moments of existential sock-drawer-related dread and subsequent bursts of 'okay, gotta make something now!' energy.

And when I create abstract work, I'm definitely tapping into a whole range of emotions, not always consciously labeling them. Sometimes a piece just feels right, and maybe, just maybe, it's processing some unspoken feeling, some tiny, lingering guilt I didn't even know was there. Perhaps that abstract piece with the sharp red slashes was, in fact, my subconscious grappling with the guilt of that abandoned painting in the corner. Creating art, even if it's not explicitly about guilt, can be a powerful way to process any difficult emotion. It's a way to externalize the internal noise.

The Viewer's Encounter with Guilt in Art

Looking at art that deals with difficult emotions like guilt can be challenging. Sometimes, you might not even realize why a piece makes you feel uneasy or introspective. It might just resonate on a subconscious level. The artist's expression taps into something you carry within.

I remember seeing a particular abstract piece once – lots of deep blues and blacks, with these sharp, almost violent slashes of red. It gave me this immediate, visceral feeling of something being wrong, a hidden pain. It wasn't depicting anything specific, but it felt like regret, like the sharp sting of realizing you messed up. That's the power of abstract art – it bypasses the literal and goes straight for the gut.

Engaging with such art can be a form of processing. It can help you identify and perhaps begin to understand similar feelings within yourself. It's a safe space to confront the uncomfortable, mediated by the artist's vision. It can even offer a sense of catharsis, allowing for emotional release. If a piece stirs up difficult emotions, consider journaling about it or discussing it with a trusted friend or therapist. Art can be a powerful catalyst for self-reflection and even a step towards healing or reconciliation with difficult pasts, whether personal or collective. How does art about difficult emotions make you feel? What thoughts or memories does it bring up? Your personal context and experiences will heavily influence how you interpret and connect with such work.

If you're interested in understanding how to look beyond the surface, my guide on how to read a painting might be helpful.

The Purpose and Impact of Art About Guilt

While confronting, art about guilt serves several crucial purposes. It acts as a mirror, reflecting uncomfortable truths about individuals, societies, and history. By externalizing these feelings, artists make them visible and shareable, fostering empathy and understanding among viewers. It can be a form of bearing witness, ensuring that difficult histories or personal struggles are not forgotten, offering a form of memorialization and validation for those affected.

Art about guilt can also be a catalyst for dialogue and critical reflection. It challenges complacency and prompts viewers to consider their own positions or complicity within systems that perpetuate injustice or suffering. This confrontation, while difficult, can be a necessary step towards personal growth or broader social change. For both the artist and the viewer, engaging with this kind of art can be incredibly cathartic, offering a space for emotional release and processing. Ultimately, it can even offer a path towards healing, reconciliation, or forgiveness – whether self-forgiveness for personal mistakes or a collective reckoning with a difficult past.

Finding Art That Resonates

If you're drawn to art that explores the deeper, more complex aspects of the human experience, including guilt, where do you look? It's about seeking out works that speak to your own internal landscape.

- Museums and Galleries: Explore modern and contemporary sections. Look for works that evoke a strong emotional response, even if it's not immediately clear why. Pay attention to pieces that use intense color palettes, distorted forms, challenging subject matter, or unconventional materials. My guides to best museums and best galleries worldwide are a good starting point. Consider visiting specific museums known for their modern or contemporary collections, like the MoMA in NYC or the Tate Modern in London. Museums focusing on social history or specific cultural narratives may also house powerful works addressing collective guilt, such as the National Museum of American History or the National Museum of China. In the Netherlands, the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam or the Kröller-Müller Museum might feature relevant modern and contemporary works.

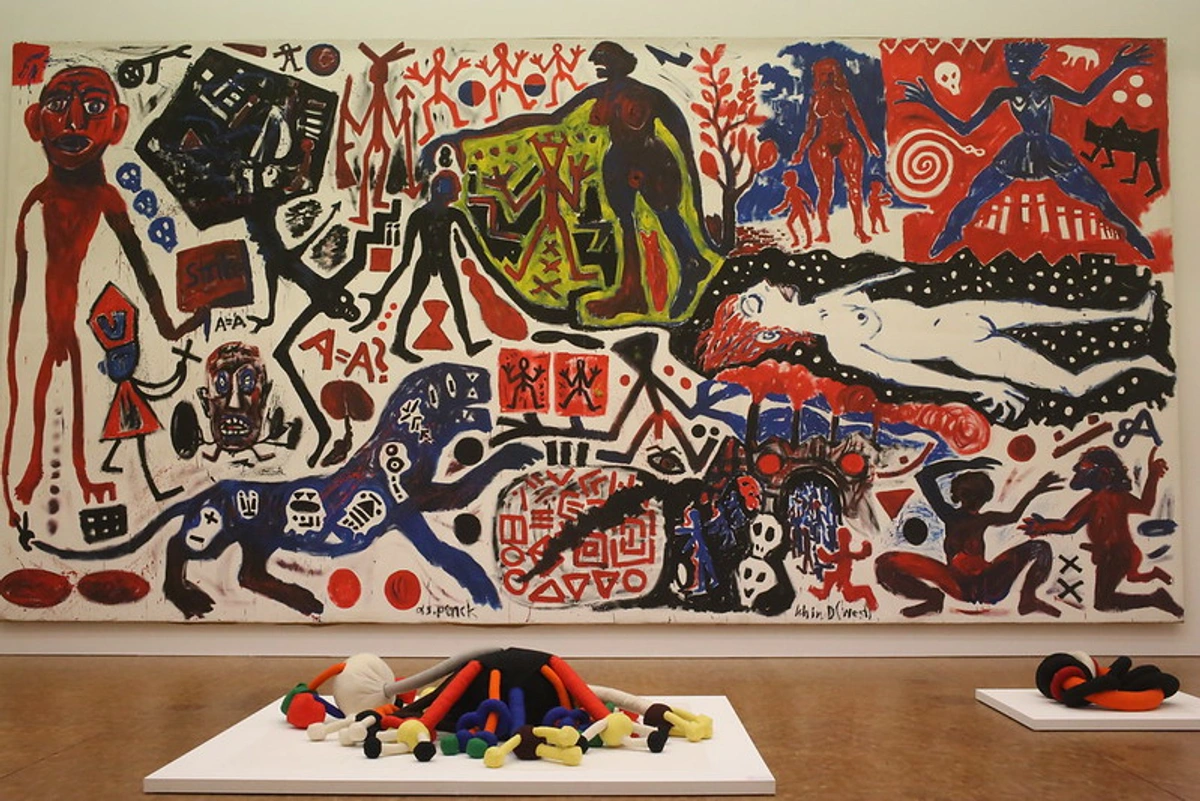

- Specific Movements: Dive into Expressionism (focused on intense subjective emotion), Surrealism (exploring the subconscious and often darker psychological states), or even certain periods of Abstract Expressionism (tapping into raw emotion). These movements, born out of periods of societal upheaval and intense introspection, often delve into themes related to anxiety, the subconscious, and the darker sides of the human psyche, which frequently intersect with guilt. Learning about their historical context can deepen your understanding. Also, look into movements or periods focused on social realism or political art, like Protest Art. Artists like Francisco Goya, particularly in his Caprichos series, used satire and dark imagery to critique societal follies and injustices, often implying a collective guilt or complicity.

- Contemporary Artists: Many living artists are directly addressing difficult themes, including personal and societal guilt, trauma, and responsibility, often through powerful and provocative work. Exploring best contemporary artists can lead you to powerful work. Look for artists whose practice involves social commentary, historical research, or deep personal introspection, such as Ai Weiwei or those featured in guides to Contemporary Art in China or Contemporary Art in Spanish-Speaking Countries. Artists like Kara Walker and Doris Salcedo, mentioned earlier, are prime examples of contemporary artists who tackle difficult histories and their lingering impact, often prompting viewers to consider themes of collective guilt or unresolved trauma. Artists addressing the aftermath of conflict or historical injustices are also highly relevant. Consider artists like William Kentridge, whose work often deals with the difficult history of apartheid in South Africa, or Christian Boltanski, who explores themes of memory, loss, and collective identity, often evoking a sense of historical burden.

- Local Art Scenes: Don't forget local galleries and artist studios! Sometimes the most resonant work is being made right in your community, reflecting shared local histories or contemporary issues. Visiting local art galleries can offer a more intimate connection to the art and the artist. You might find artists directly addressing local histories or community-specific burdens. My own museum in 's-Hertogenbosch, for example, often features work that explores local or personal narratives that can touch on complex emotions. You can find out more about it here.

- Online Resources: The internet has opened up vast possibilities for discovering art. Explore online galleries, artist websites, and social media platforms. Many artists share their process and the themes behind their work directly. This can be a great way to find emerging artists or those working on very specific, personal themes related to guilt or trauma. Just be sure to research the artist and platform carefully, especially if you're considering purchasing. My guide on how to buy art online might be helpful here.

- Trust Your Gut: Don't overthink it. If a piece makes you feel something, lean into it. Art doesn't always need a label or a clear explanation. It's okay to just feel it. Your emotional response is a valid way to connect with the art. Sometimes the artist's intention is less important than the viewer's experience. If you're curious about the artist's perspective, look for an artist statement or check their website or biography for clues about their themes and intentions.

If you're considering adding art to your own space that speaks to you on a deeper level, whether it's about guilt or joy or anything in between, check out my guide on how to buy art. And of course, you can always explore the pieces available for sale on my site – maybe one will resonate with your own internal landscape.

FAQ: Art and Guilt

Q: Is all art that uses dark colors about guilt?

A: Absolutely not! Dark colors can convey many things – mystery, solemnity, power, or simply be part of a composition. Color is complex, and artists use it in myriad ways to create mood and meaning.

Q: How can I tell if an artist is trying to express guilt?

A: Look at the title (if any), the artist's statement (artist statement explained), the context of their other work, and the historical/cultural background. Artists often leave clues! But most importantly, pay attention to how the piece makes you feel. Art is subjective, and your interpretation is valid. Sometimes the artist's intention is less important than the viewer's experience.

Q: Can looking at art about guilt help me process my own feelings?

A: For many people, yes. Art can provide a sense of validation, showing you that you're not alone in experiencing difficult emotions. It can also offer new perspectives or simply a space for quiet contemplation and emotional release. It's like having a silent conversation with the artist and the work. It can help externalize and make sense of internal turmoil.

Q: Can creating art about guilt help the artist process their feelings?

A: Absolutely. The act of creation can be incredibly cathartic. Translating an internal, often chaotic, feeling like guilt into a tangible form – whether it's a painting, sculpture, or performance – can help externalize it, make it feel more manageable, and offer a new perspective on the emotion. It's a form of visual or performative therapy.

Q: How is guilt in art different from shame in art?

A: While often intertwined, guilt is typically associated with a specific action or inaction ("I did something bad"), whereas shame is a more pervasive feeling about one's self ("I am bad"). Art can depict this difference through subject matter (e.g., depicting a specific transgression vs. depicting a figure hiding or physically shrinking) or through the emotional tone conveyed. Some art might deliberately blur the lines, reflecting how these emotions often feel indistinguishable to the person experiencing them. Think of it this way: Guilt says, "I did a bad thing." Shame says, "I am a bad person."

Q: Are there specific art movements known for exploring guilt?

A: While not exclusively about guilt, movements like Expressionism (focused on intense subjective emotion), certain aspects of Surrealism (exploring the subconscious and often darker psychological states), and even some forms of contemporary political or social commentary art often delve into themes related to guilt, anxiety, and the darker sides of the human psyche. These movements provided artists with the visual language to express complex internal states. Historical periods focused on religious or moral themes, like the Medieval and parts of the Renaissance and Baroque, also heavily featured depictions related to sin and repentance. Romanticism and Symbolism also explored inner turmoil and the weight of difficult emotions.

Q: Where can I see famous examples of art related to guilt?

A: Many major museums worldwide house works that touch upon this theme, often within their collections of religious art, Expressionism, Surrealism, or modern and contemporary art. The best museums in Europe or the best museums in the US are good places to start your search. Look for artists known for exploring intense emotions or societal issues, such as Edvard Munch, Francisco Goya (whose "Caprichos" series critiques societal follies and their consequences, often implying guilt), Anselm Kiefer, or contemporary artists dealing with social justice themes like Kara Walker or Doris Salcedo. Picasso's "Guernica," while primarily about the horrors of war, certainly evokes a sense of collective guilt and suffering. Works by artists addressing the aftermath of conflict or historical injustices are also highly relevant. Specific museums like the Museo Reina Sofía in Madrid (home to Guernica) or the MUNCH Museum in Oslo are key places to explore.

Q: Can art about guilt have a positive purpose?

A: Absolutely. While confronting, art about guilt can serve several positive purposes. It can foster empathy by allowing viewers to connect with the depicted struggle. It can prompt critical reflection on personal or societal issues, potentially leading to greater understanding or even social change. For the artist, it can be a powerful tool for processing difficult emotions and finding a form of healing or reconciliation. It reminds us that these feelings are part of the shared human experience, reducing isolation. It offers a path not just to confrontation, but potentially to understanding, empathy, and even a form of reconciliation. It can also act as a form of memorialization or bearing witness to difficult truths.

Art about guilt isn't always easy, but it's important. It reminds us of our shared humanity, our capacity for error, and our ongoing struggle to make peace with our pasts, both personal and collective. It's a powerful testament to the fact that art isn't just about beauty; it's about truth, in all its messy, uncomfortable glory. And sometimes, facing that truth on a canvas is the first step to facing it within ourselves. It offers a path not just to confrontation, but potentially to understanding, empathy, and even a form of reconciliation.