What is Stained Glass Art? A Deep Dive into Its History & Magic

Uncover the enchanting world of stained glass art. From ancient cathedrals to Tiffany lamps, explore its rich history, intricate techniques, and enduring appeal in this personal guide.

Stained Glass Art: A Comprehensive Guide to Its History, Techniques, and Enduring Magic

There are certain art forms that just… get to you, aren't they? For me, the moment sunlight pierces a piece of stained glass, transforming mundane light into a cascade of vibrant, shifting colors, well, that's pure magic. It’s a sensory experience that goes beyond mere aesthetics, a quiet awe that can stop you dead in your tracks. I mean, who hasn't walked into an old cathedral or a beautifully designed public space and been mesmerized by those monumental, glowing narratives? It feels like stepping into a different dimension, doesn't it? It’s a phenomenon, really, how something so seemingly rigid can create such fluidity of light and feeling – a truly universal appeal that transcends cultures and eras, speaking a language all its own.

The very act of light passing through colored glass seems to imbue a space with a different kind of energy, doesn't it? It’s a silent, dynamic presence that changes with the time of day, with the seasons, with every passing cloud. This isn't static art; it's a living, breathing component of architecture and atmosphere, something truly special. It's a dialogue between human ingenuity and the boundless energy of the sun, making each piece a unique, ephemeral performance.

I’ve always been fascinated by how light, one of the most ephemeral things, can be harnessed and shaped by something as solid as glass. It’s a bit like capturing a rainbow and holding it in your hand, a true alchemy of material and illumination. This isn't just about pretty pictures; it’s about a profound interplay of art, craft, science, and a deep, often spiritual, intention, fundamentally tied to what is design in art. This article aims to be your most comprehensive guide, filling a content gap and establishing a new topic area for those curious about this specific art form. Join me as we journey through the fascinating world of stained glass, exploring its ancient origins, intricate techniques, profound significance, and its vibrant presence in the modern artistic landscape. I promise, you'll never look at a sun-drenched window the same way again. We'll delve into the very chemistry of color, the hands-on craft, and the profound impact this luminous medium has had, and continues to have, on our world.

Unveiling the Magic: What Stained Glass Art Truly Is

The Allure of Stained Glass: A Brief Overview

Before we dive deep, let's just take a moment to appreciate what makes stained glass so captivating. It’s more than just a decorative element; it's an architectural marvel, a storyteller, and a manipulator of light that has transcended cultures and centuries. Whether it's the towering biblical scenes in a Gothic cathedral or a delicate Art Nouveau lamp, stained glass holds a unique power to transform a space and evoke emotion. It’s a medium that truly lives, changing with the light of day, offering an endless, ephemeral performance. This isn't merely about static beauty; it's about dynamic interaction and a constant dialogue between the artwork and its environment. It's about capturing light itself and weaving it into a tangible narrative, or simply allowing it to dance in abstract patterns, a visual symphony for the eyes.

So, What Exactly IS Stained Glass Art?

At its core, stained glass art is about creating images or patterns from pieces of colored glass. These pieces are then held together, traditionally by strips of lead, forming a cohesive panel. Think of it as a luminous puzzle. The 'stain' part doesn't always mean the glass itself is stained with paint; often, the color is inherent in the glass, a result of various metallic oxides added to the molten glass during its manufacturing process. These metallic oxides (like cobalt for serene blues, copper for fiery reds or verdant greens, manganese for purples, and iron for warm yellows or earthy browns) introduce specific ions into the glass matrix that selectively absorb and transmit certain wavelengths, resulting in the brilliant colors we see. For example, a tiny amount of gold can produce ruby red glass, while varying concentrations of iron can yield various greens or yellows, or even a subtle blue-green tint depending on the oxidation state. This isn't just about adding pigment; it's about the very atomic structure of the glass itself, absorbing and transmitting different wavelengths of light – a true marvel of material science and artistry. So yes, it's a bit of a misnomer in some ways, but the term has stuck through centuries, encompassing both truly stained and inherently colored glass, and even techniques that involve painting directly onto the glass. When I look at a piece, I'm always thinking about the subtle science behind the glow, as much as the artistry; it's a constant reminder of the magic of chemistry at play. It's an art form that masterfully manipulates the optical properties of glass to create dazzling effects, transforming light into an active, dynamic component of the artwork itself.

The Basic Anatomy of a Stained Glass Panel: A Luminous Blueprint

Think of a stained glass panel as a meticulously constructed tapestry woven from light and solid material. It's a layered process, where each component plays a vital role in the final, breathtaking effect. Understanding this fundamental structure helps demystify the magic and highlights the incredible craftsmanship involved.

Before we delve into the specific materials, it's helpful to understand the fundamental components and the high-level process that brings a stained glass panel to life. At its heart, it involves:

- Conceptualization & Design: This initial phase is where the artistic vision takes shape, evolving into a detailed blueprint known as a 'cartoon.' It's a complex puzzle solved on paper, meticulously outlining every glass piece, its color, and the lead or foil lines, often including notes for painted details. This step requires immense foresight in composition, design, and structural planning.

- Glass Selection: This is a crucial, almost intuitive step, where the artist acts like a painter selecting pigments, but with an added dimension: light. Each piece of colored glass is chosen not just for its hue, but for its texture, opacity, and how it will refract, reflect, and transmit light, influencing the overall luminosity and mood of the piece.

- Cutting & Shaping: This involves the precise art of scoring and breaking glass. Using specialized tools, each piece is cut to match the cartoon's intricate shapes. For complex curves, "grozing" (nipping small pieces of glass) refines the edges, ensuring a perfect, snug fit, which is paramount for structural integrity and a clean aesthetic.

- Assembly: The individual glass pieces are then carefully fitted together. Traditionally, they are secured within channels of H-shaped lead came, which provides both structure and a bold outline. Alternatively, in the copper foil method, each piece is meticulously wrapped in adhesive-backed copper foil, allowing for finer lines and more intricate designs.

- Soldering & Finishing: The joints of the lead came or the copper foil seams are meticulously soldered together, creating a strong, unified metallic grid. For leaded work, a final cementing process involves applying a waterproof putty under the lead flanges, sealing the panel against weather and providing crucial rigidity for longevity. For foiled work, sealants ensure similar protection. The piece is then cleaned and polished, ready to begin its luminous life.

This intricate framework underpins centuries of innovation and artistry, demonstrating a harmonious blend of artistic vision and rigorous craft. Now, let's look at the humble materials that make it all possible.

The Humble Materials: More Than Meets the Eye

It sounds simple, right? Just glass and lead. But oh, the possibilities! You're working with:

- Colored Glass: This is truly the star of the show, the very soul of the artwork. It comes in countless hues, textures, and opacities, each with its own personality and way of interacting with light. Beyond the transparent Cathedral glass (often found in traditional church windows, allowing maximum light passage and intense color saturation) and opaque Opalescent glass (like the kind Tiffany famously used, with a milky, iridescent, and often streaky quality that diffuses light beautifully), you'll encounter a fascinating array of types. These include Flashed glass (a thin layer of one color fused to a base of another, allowing for intricate engraving or etching to reveal the underlying color), Antique glass (hand-blown with natural striations and bubbles, prized for its organic character and often used for historic reproductions), Streaky glass (a blend of two or more colors swirled together, creating organic patterns ideal for naturalistic scenes like skies or water), Whispy glass (a less dense form of streaky opalescent glass, often used for clouds), and even specialty glasses with ripple, hammered, or reamy textures that distort light in intriguing ways. Each piece is chosen not just for its color, but for how it interacts with light – how it glows, reflects, and casts shadows, contributing to the overall luminosity and mood of the piece. I’ve seen artists spend hours just holding pieces up to the light, almost having a conversation with them, understanding their unique personality and potential. It’s not unlike a painter carefully selecting a pigment, but with glass, the medium itself dictates much of the final luminosity, a dance between intention and material, and often a happy discovery in the process.Let's break down some common glass types: | Glass Type | Characteristics | Typical Use | Additional Notes | | :---------------- | :---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- | :------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ | :---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- | | Cathedral | Transparent, smooth, often machine-rolled, allows maximum light passage and brilliance. Comes in a wide range of intense, saturated colors. | Traditional church windows, large architectural panels, general decorative work, abstract designs. | Offers intense light transmission and brilliant color saturation. Ideal for dramatic effects. | | Opalescent | Opaque to semi-opaque, milky, often streaky or mottled, diffusing light for a soft glow. Prevents full visibility through the glass. | Tiffany lamps, decorative panels, modern art, interior design, privacy screens. | Prized for its ability to diffuse and soften light, creating a painterly effect. Often used to depict skin tones or clouds. | | Flashed | A thin layer of one color fused to a base of another, often clear or a contrasting color. This allows for intricate engraving or etching. | Engraving, etching, intricate details where underlying color needs to be revealed. | Creates nuanced effects; the surface color can be removed to expose the base color, adding depth and detail. | | Antique | Hand-blown, characterized by natural striations, bubbles (called 'seeds'), and uneven thickness. Prized for its organic character and historical authenticity. | Historical restoration, traditional designs, character pieces, art seeking an authentic, aged look. | Valued for its unique imperfections, which lend a vibrant, living quality to the light passing through. Often more expensive due to artisanal production. | | Streaky | A blend of two or more distinct colors swirled together during manufacturing, creating organic patterns and movement within the glass. | Organic designs, landscapes (skies, water, foliage), abstract work, modern art. | Excellent for depicting natural elements and creating a sense of fluidity and depth with inherent color blending. | | Ripple/Hammered| Textured surfaces created by rolling molten glass between patterned rollers, designed for light distortion, visual interest, and privacy. | Decorative elements, privacy panels, abstract pieces, backgrounds, borders. | The varied surface refracts light dramatically, adding sparkle and movement. Can obscure views while still allowing light. | | Wispy | A less dense form of streaky or opalescent glass, often with soft, feather-like wisps of opaque color mixed into a more translucent base. | Skies, clouds, misty scenes, delicate natural elements, ambient light diffusion. | Provides a delicate, ethereal quality, ideal for depicting atmospheric conditions or soft transitions. | | Mottled | Opalescent glass with distinct, irregular patterns or concentrations of more intense color, resembling blotches or spots. | Abstract work, organic forms, decorative panels, creating visual weight and interest. | Offers unique, non-uniform coloration that can add character and a painterly feel to a piece, differing from the smooth blend of streaky. |

- Lead Came (or Copper Foil): These are the structural bones, the sinews that hold the luminous body of the artwork together. Traditionally, H-shaped lead strips (called 'came'), available in various profiles (from slender flat Cames for delicate work to broader, bolder Cames for structural integrity, and U-shaped Cames for panel edges), hold the glass pieces together, offering robust support and a classic, bold outline. The choice of came profile is crucial, impacting both the structural strength and the aesthetic of the finished piece. The use of lead dates back centuries, providing both structure and a defining dark line that enhances the artwork, often referred to as the 'patina of time' as it oxidizes and darkens. While lead is incredibly durable, it can sag over time in very large, unsupported panels and requires careful handling due to its toxicity. More recently, especially since the late 19th century, the copper foil method (hello, Tiffany!) allows for much finer, more intricate designs and the creation of three-dimensional objects like lampshades, where the thinner solder lines create a more delicate aesthetic. You'll also find modern alternatives, like rigid zinc, brass, or even electroplated copper came, offering different aesthetic and structural properties, showcasing the ongoing evolution of the craft and providing options for lead-free projects, particularly important for items that might be handled frequently or in public spaces. Each choice of came or foil profoundly influences the final visual weight and character of the piece, transforming the raw glass into a coherent, luminous form.

- Solder: Ah, the unsung hero! This is the metal alloy that, when melted with a soldering iron, flows into the seams, permanently joining the lead came or copper foil lines. Traditionally, a 60/40 tin-lead alloy (60% tin, 40% lead) is common, valued for its malleability, strength, and relatively low melting point, making it easy to work with and producing smooth, shiny beads. However, contemporary artists increasingly opt for lead-free solders (typically tin-copper or tin-silver alloys) for safety and environmental reasons, especially when the artwork is in a public space, a home with children, or handled frequently. While lead-free solders can be harder to work with and require higher temperatures, their benefits are clear, making them a responsible choice for modern creations. The type of solder chosen, and its subsequent finish, can also profoundly affect the final appearance, with different polishes and patinas (such as black, copper, or bronze) available to complement or contrast with the glass and frame, adding an extra layer of artistic consideration. It’s what transforms individual elements into a unified, structurally sound artwork, a quiet act of cohesion that binds the luminous puzzle together. Beyond the standard alloys, there are also solders designed for specific aesthetic purposes, for example, those that accept a darker patina more readily, further enhancing the definition of the lead lines.

- Putty/Cement: Applied to seal the panel, making it waterproof and strengthening it against the elements. This often-overlooked paste – typically a mix of linseed oil, whiting (calcium carbonate), and lampblack or other pigments – is worked meticulously under the lead flanges using a specialized cementing tool. This traditional method fills any tiny gaps between the glass and the came, prevents rattling of the glass pieces, provides crucial rigidity, and is absolutely vital for the longevity of a piece, especially in outdoor installations exposed to the elements, protecting against wind pressure and temperature fluctuations. For copper foil work, a chemical sealant, grout, or even silicone can be applied to provide similar waterproofing and structural stability. It’s the final embrace that makes the panel truly robust against time and weather, silently contributing to its decades, even centuries, of endurance by protecting against moisture ingress, structural fatigue, and even preventing condensation buildup. The quality and application of this cement can be the difference between a piece that lasts a few decades and one that endures for centuries.

A Glimpse Through History's Colorful Lens: From Ancient Origins to Modern Revival

Stained glass isn't a modern invention; its roots stretch back to ancient times. I often find it humbling to think about artisans working with these materials centuries ago, without all our modern tools, yet creating something so utterly breathtaking. It makes me wonder about their patience, their vision. Anyway, where was I? History! But before we dive into the grand cathedrals, it’s worth a quick detour into its even earlier beginnings.

Ancient Roots and Early Innovations: From Beads to Basilicas

While the monumental windows of the Middle Ages often grab all the glory, the story of colored glass in art actually stretches back much further, hinting at the magic of transmitted light. I'm talking about ancient civilizations, long before the soaring Gothic cathedrals we often envision!

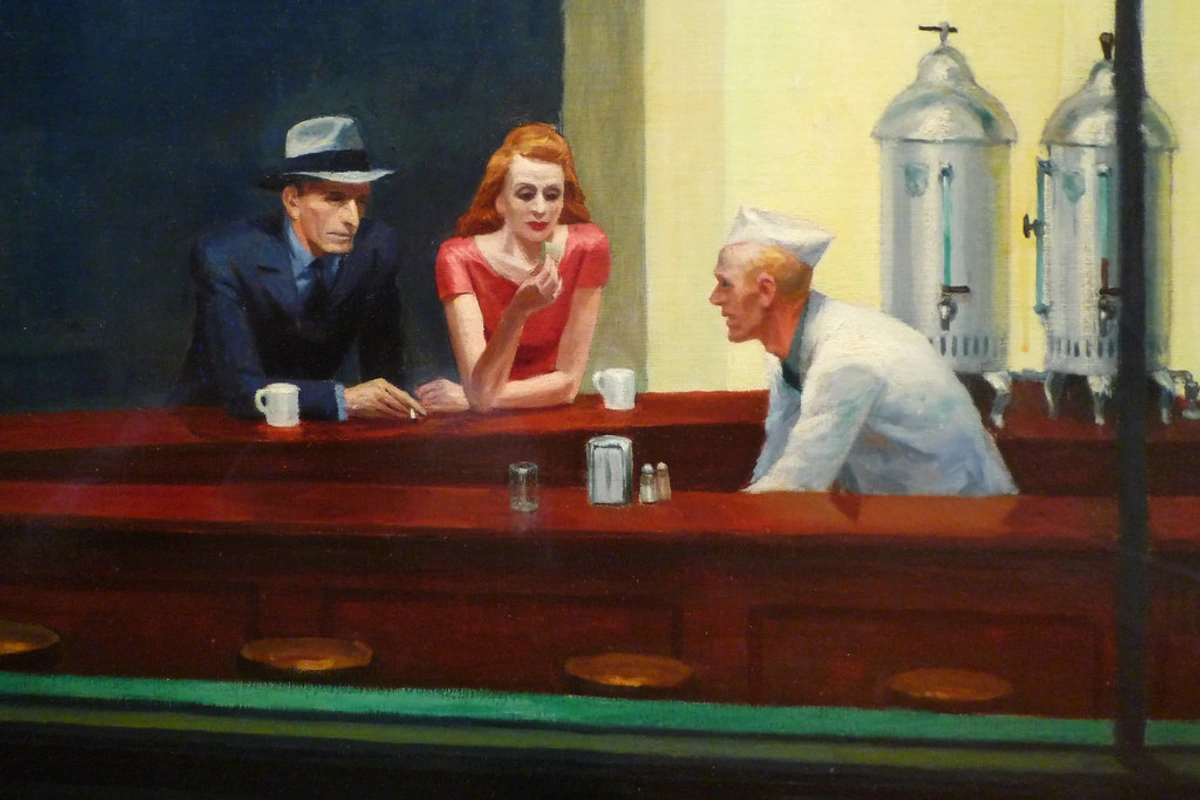

credit, licence

Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia: The genesis of glassmaking can be traced back to Mesopotamia around 3500 BCE, with the Egyptians quickly adopting and refining the craft. They were masters of colored glass as early as 1500 BCE, developing sophisticated techniques not for windows, but primarily for small, luxury objects like beads, amulets, intricate jewelry, and cosmetic containers. These early forms, often opaque and vibrant, demonstrated an astonishing early appreciation for glass as a decorative medium, valued for its beauty and perceived rarity. Imagine the painstaking effort to create those tiny, jewel-like objects without modern tools, meticulously grinding and shaping each piece! Their use of glass, often in combination with faience and other precious materials, shows a clear early understanding of its decorative potential, even if not yet as a light-filtering architectural element.

The Roman Empire: The Romans truly started exploring glass's architectural potential, albeit in different ways. They used colored glass extensively in elaborate mosaics, creating stunning floor and wall decorations, often depicting mythological scenes or geometric patterns. Critically, they also began incorporating small window panes into their opulent villas, public baths, and temples, sometimes including rudimentary forms of translucent colored glass held in wooden or metal frameworks. These often served as decorative screens or light filters rather than fully pictorial windows, showcasing an early form of light manipulation within interior spaces. Roman innovations in glass blowing and casting also allowed for larger, clearer sheets of glass than previously possible, setting the technical stage for future advancements, even if widespread colored windows were still centuries away. This shows a clear lineage towards controlling light for aesthetic and atmospheric effect, setting the stage for future developments.

Early Christian and Byzantine Eras: As the Roman Empire transitioned, early Christian basilicas began incorporating windows, initially using thin sheets of alabaster or marble to filter and soften light in sacred spaces. This served as a precursor, demonstrating a deep-seated desire to control and imbue spaces with a diffused, spiritual glow. Concurrently, the Byzantine Empire (from the 4th to 15th centuries) and the flourishing Islamic world (particularly from the 8th century onwards) played a crucial role in preserving and advancing glassmaking techniques. Byzantine mosaics, renowned for their shimmering gold and vibrant glass tesserae, further refined the use of colored glass for interior illumination and spiritual narrative. Islamic artisans, for example, excelled in crafting mosque lamps, intricate vessels, and elaborate window grilles filled with small, often geometric pieces of colored glass. These designs, found from Spain to Central Asia, not only demonstrated technical prowess but also foreshadowed the segmented approach and luminous storytelling of later European stained glass, particularly in their intricate geometric patterns and the use of small, faceted glass to create dazzling effects. This rich tapestry of ancient innovation, from tiny beads to early architectural inserts, laid the quiet groundwork for the explosion of color to come in medieval Europe.

The Medieval Masterpieces (and the Rise of Gothic)

The shift from small, utilitarian glass pieces to monumental, narrative windows truly defines the medieval period. It's here that stained glass became not just art, but an integral part of the spiritual and architectural experience.

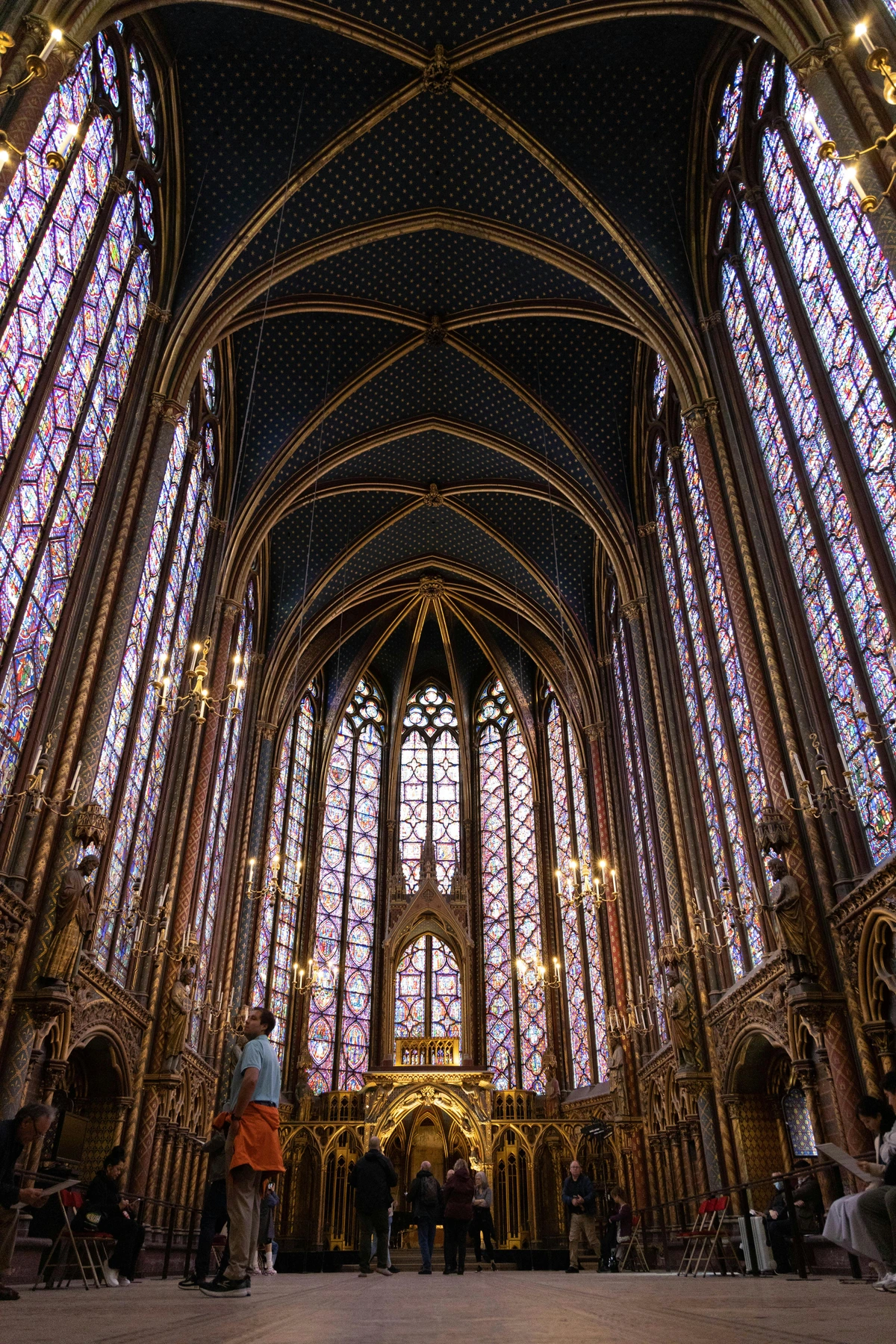

Most people, when they think of stained glass, immediately picture majestic cathedrals. And they wouldn't be wrong. The medium truly soared during the Medieval period, especially with the advent of Gothic architecture. Think of the soaring, jewel-toned walls of places like Chartres Cathedral in France, with its famous deep blues often called "Chartres blue," Canterbury Cathedral in England, or the magnificent York Minster, home to the Great East Window. These aren't just windows; they are monumental tapestries of light, often covering thousands of square feet. The sheer scale and the intricate craftsmanship are breathtaking.

It was more than just decoration; these windows were literally the illuminated scriptures of their time, often referred to as the "Bible of the Poor." Illiteracy was widespread, so the glass panels served as vivid visual narratives, telling biblical stories, lives of saints, and theological concepts to a largely unlettered congregation. Imagine trying to get your spiritual education through sermons alone – these windows must have been a revelation, literally. They transformed dark, imposing structures into ethereal spaces filled with divine light, fostering a profound spiritual experience for worshippers, making the abstract concepts of faith tangible and visible. The very architecture of these cathedrals was designed around these luminous narratives.

During the Gothic era, the engineering advancements (like the flying buttress) allowed for massive window openings, turning solid stone walls into veritable screens of glass. This wasn't just decorative; it was fundamental to the very structure and spiritual experience of a Gothic cathedral, blurring the lines between structural support and artistic expression. The development of new glassmaking techniques, such as the ability to produce larger sheets and more consistent colors, further fueled this artistic explosion. These windows were not just placed in the architecture; they were the architecture, defining the interior space with light and story.

Renaissance Slump and Victorian Revival

Every art form has its ebb and flow, its moments in the spotlight and its periods of quiet retreat. For stained glass, the Renaissance brought a significant shift, only to be gloriously resurrected in the Victorian era.

After the medieval heyday, stained glass took a bit of a back seat during the Renaissance (roughly 14th to 17th centuries). This was a period when artists were more interested in illusionistic fresco painting and sculpture, pushing boundaries in perspective in art and anatomical realism. The emphasis shifted dramatically from the symbolic, filtered light of medieval cathedrals to naturalistic light and chiaroscuro (the use of strong contrasts between light and dark) in painting. This meant that the painterly effects of stained glass, which rely on light passing through colored glass, were less valued than the illusion of depth and form achieved on opaque surfaces. Furthermore, the Protestant Reformation, which began in the 16th century, often led to the iconoclastic destruction of religious imagery, including vast quantities of stained glass, in favor of simpler, unadorned church interiors. Stained glass was frequently relegated to less prominent roles, or even removed from churches in favor of clear glass that allowed more natural light (and a better view of those stunning frescoes!). It was a challenging period for the medium, with its reputation declining, but art, as I always say, finds a way. Despite this decline, isolated pockets of skilled artisans continued the tradition, often working for private patrons or in less publicly visible settings, ensuring the craft never completely died out.

But art is cyclical, isn't it? Thankfully! The Victorian era (roughly 1837-1901) saw a glorious renewed interest, largely fueled by the Gothic Revival movement which sought to re-establish medieval aesthetics, craftsmanship, and spiritual values. Influential figures like the architect Augustus Pugin championed a return to the moral and artistic principles of medieval craftsmanship, viewing stained glass as integral to authentic Gothic design, lamenting its decline and advocating for its reintroduction into churches and public buildings. Alongside this, the Arts and Crafts Movement, spearheaded by figures like William Morris, Edward Burne-Jones, and Charles Rennie Mackintosh (though more closely associated with Art Nouveau, he shared this ethos), championed handmade quality and traditional skills, and the integration of art into everyday life, finding a perfect outlet in stained glass. Major studios like William Morris & Co. (founded by William Morris himself, a seminal figure in design history) and Clayton & Bell became prolific, creating new windows for churches and public buildings across England and beyond, often drawing inspiration directly from medieval designs but also introducing their own distinctive styles. People started appreciating the craftsmanship, the narrative power, and the spiritual resonance of the medium once more, moving it beyond mere decoration and paving the way for something truly spectacular and quite modern for its time, culminating in the dazzling innovations of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The Art Nouveau Revolution and Tiffany's Legacy

Ah, Art Nouveau! A period of exquisite craftsmanship, fluid lines, and organic forms, a true embrace of nature's beauty in art, flourishing from roughly 1890 to 1910. This is where stained glass truly re-entered the popular imagination, moving beyond ecclesiastical settings and into elegant homes, public buildings, and even subway stations. And one name dominates this era, a true visionary: Louis Comfort Tiffany.

Tiffany didn’t invent stained glass, but he revolutionized it. His genius lay in his innovative use of glass itself and his commitment to developing new techniques. Art Nouveau, with its characteristic fluid lines, organic forms, and emphasis on natural motifs (think whiplash curves, botanical elements, and flowing hair), found a perfect partner in stained glass, embodying the movement's desire to integrate art into all aspects of life. He developed unique glass types, such as Favrile glass, known for its iridescent surface, rich, swirling colors, and unique textures, which he manufactured in his own studios to achieve specific luminous effects. Favrile glass was truly groundbreaking, allowing for subtle tonal shifts and a depth of color that mimicked natural phenomena. His widespread adoption of the copper foil method allowed for much smaller, more intricate glass pieces, creating breathtaking lampshades, windows, and decorative objects with unparalleled detail and subtle gradations of color and texture, freeing the medium from the heavier lead lines of traditional methods. Other notable Art Nouveau artists, like Charles Rennie Mackintosh (whose architectural designs often incorporated stained glass with geometric precision and symbolic motifs, particularly in Glasgow), Antoni Gaudí (whose Sagrada Familia in Barcelona is a kaleidoscope of light, often abstract and flowing, using stained glass to create a truly spiritual atmosphere, defining interior spaces with its luminous energy), and Alphonse Mucha, also incorporated stained glass into their architectural and decorative schemes, further cementing its place in this vibrant movement. Their collective work brought stained glass into a new era of decorative arts, where nature, myth, and exquisite craft converged, often blurring the lines between fine art and functional design and making it accessible for domestic settings.

The Rise of Art Deco Stained Glass

Following the flowing, organic lines of Art Nouveau, the Art Deco movement (roughly 1920s-1930s) ushered in a new aesthetic for stained glass, characterized by sleek, geometric forms, bold lines, and a celebration of modernity and industrial design. While less narrative than its predecessors, Art Deco stained glass often featured stylized motifs, sunbursts, chevrons, and abstract patterns, utilizing strong, vibrant colors often set against clear or frosted glass. It found its home in grand public buildings, luxury liners, and the chic interiors of the era, offering a dazzling, sophisticated take on the art form. Think of the dazzling lobbies of skyscrapers like the iconic Chrysler Building in New York (which famously features stained glass in its lobby) or the opulent ocean liners of the 1920s and 30s, where stained glass became a statement of streamlined elegance and technological progress, a stark contrast to the historical themes of Gothic cathedrals. This era truly showcased how a single medium can adapt and transform to reflect such radically different sensibilities in art movements, moving away from historical mimicry towards a distinctly modern visual language, celebrating a new machine age aesthetic.

Following the flowing, organic lines of Art Nouveau, the Art Deco movement (roughly 1920s-1930s) ushered in a new aesthetic for stained glass, characterized by sleek, geometric forms, bold lines, and a celebration of modernity and industrial design. While less narrative than its predecessors, Art Deco stained glass often featured stylized motifs, sunbursts, chevrons, and abstract patterns, utilizing strong, vibrant colors often set against clear or frosted glass. It found its home in grand public buildings, luxury liners, and the chic interiors of the era, offering a dazzling, sophisticated take on the art form. Think of the dazzling lobbies of skyscrapers like the Chrysler Building in New York, or the opulent ocean liners of the 1920s and 30s, where stained glass became a statement of streamlined elegance and technological progress, a stark contrast to the historical themes of Gothic cathedrals. This era truly showcased how a single medium can adapt and transform to reflect such radically different sensibilities in art movements, moving away from historical mimicry towards a distinctly modern visual language.

Beyond the Window Pane: Diverse Applications of Stained Glass

When we think of stained glass, the first image that comes to mind is almost always a towering cathedral window, right? And for good reason! But the truth is, this luminous art form has graced far more spaces and taken on a surprising variety of forms throughout history and even today. It’s an incredibly versatile medium, I think, capable of adapting to almost any context where light and color can make an impact.

Let's explore some of its diverse applications:

Application | Description | Examples | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Architectural Features | Beyond flat windows, stained glass is integrated into domes, intricate skylights, entire walls, or ceilings, transforming interior spaces with dramatic, shifting light and color. | Grand hotel lobbies, public libraries, airport terminals, modernist churches, train stations, shopping malls. | Creates immersive environments; light becomes an active design element, influencing mood and perception of space. Often large-scale and site-specific. |

| Lamps and Lighting Fixtures | Thanks to the Art Nouveau movement and Louis Comfort Tiffany, these are sculptural artworks that bring warmth, color, and intricate patterns into a room, serving as both art and illumination. | Table lamps, floor lamps, elaborate chandeliers, wall sconces, ceiling fixtures, nightlights. | Provides ambient or accent lighting with decorative appeal; diffuses light beautifully, casting colored patterns onto surrounding surfaces. Often 3D. |

| Domestic Settings | A long tradition in private homes, offering aesthetic beauty, a degree of privacy, and a unique personal touch. | Decorative transoms above doorways, cabinet door inserts, unique entryway panels, privacy screens, sidelights, window hangings. | Enhances home aesthetics, adds character, and can control light and privacy in a softer way than curtains or blinds. Reflects personal style. |

| Decorative Panels | Smaller, non-architectural panels that offer a splash of color and privacy without completely blocking light, often movable or temporary. | Hung in windows, incorporated into doors, freestanding room dividers, wall art, triptychs, framed pieces. | Versatile for bringing light and color into a space without permanent installation; can be repositioned or moved. Often serves as a focal point. |

| Functional Art Objects | Bringing the unique interplay of glass and light into everyday objects, elevating the mundane to the magical, making ordinary items extraordinary. | Decorative boxes, jewelry, cabinet inserts, framed mirrors, ornaments, coasters, suncatchers, clock faces, small sculptures. | Blurs the line between art and utility; makes common objects feel precious and unique through the incorporation of colored glass. |

| Contemporary Sculptural Applications | Moving beyond purely functional or architectural roles, standalone sculptures interact with ambient light, forming dynamic installations and exploring abstract or conceptual themes. | Gallery installations, outdoor garden sculptures, public plazas, interactive light art, freestanding forms. | Explores glass as a sculptural medium, interacting with its environment and changing with light conditions. Often abstract, experimental, and pushes material boundaries. |

| Secular Commissions and Public Art | Found in airports, hospitals, university buildings, corporate headquarters, and government buildings, reflecting contemporary themes, civic pride, or abstract visions. | Memorial windows, community art projects, corporate lobby installations, civic centers, university chapels, subway stations. | Art for the public sphere, often conveying messages, commemorating events, or simply enhancing civic spaces with beauty and inspiration. Durable and impactful. |

| Signage and Advertising | Historically and sometimes today, used for elegant and eye-catching store signs, illuminated advertisements, or distinctive brand identification. | Vintage pub signs, custom business logos in specialty glass, illuminated storefronts, historical pharmacy signs. | Provides a unique, upscale, and memorable visual identity; light enhances visibility and aesthetic appeal, often associated with craftsmanship. |

| Religious and Spiritual Spaces | The original and arguably most impactful application, creating sacred atmospheres, conveying narratives, and evoking spiritual contemplation. | Cathedrals, churches, mosques, synagogues, temples, meditation centers, memorial chapels. | Creates a profound sense of awe and reverence, transforming interior light into a spiritual presence. Central to many architectural traditions. |

| Glass Wall Art & Murals | Large-scale installations that function as luminous murals, often integrated directly into interior walls or freestanding as room dividers. | Corporate headquarters, luxury residences, hotels, exhibition spaces, civic buildings. | Combines the monumental scale of a mural with the dynamic, light-filtering qualities of stained glass, creating vibrant, shifting backdrops. |

It’s this adaptability, this capacity to move from the sacred to the everyday, from monumental to intimate, that keeps me so endlessly fascinated by stained glass. It truly lives up to its potential as an art form that transforms any environment it inhabits.

The Crafting Journey: From Idea to Illumination

Before we dive into the specifics of each technique, it’s worth pausing to appreciate the entire journey a stained glass piece undertakes, from an initial spark of inspiration to its final, glowing installation. It’s a demanding but incredibly rewarding process that marries artistic vision with meticulous craftsmanship. Think of it as a meticulously choreographed dance between concept and execution, where every step is critical.

- Conception & Design (The "Cartoon"): Every piece begins with an idea, which is then translated into a detailed, full-scale blueprint traditionally called a cartoon. This isn't just a rough sketch; it's a precise map dictating every individual glass piece, its specific color, and the exact lines where the lead came or copper foil will eventually run. From this master cartoon, a separate cutline pattern is meticulously created, often using specialized pattern shears that remove a tiny sliver of paper to account for the thickness of the lead or foil (known as the 'kerf'). It’s a complex puzzle solved on paper, often including painted details or grisaille effects (monochromatic painting on glass to create shading and detail), before a single piece of glass is even touched, demanding immense foresight in composition and design. This initial planning is the backbone of the entire project, preventing costly errors down the line.

- Material Selection: The artist then meticulously selects the glass, considering not just color and hue, but also texture, opacity, and how each piece will interact with light under various conditions. This is where the magic truly begins, as the artist envisions the play of light through the chosen hues, sometimes holding pieces up to the light for hours, almost communing with the material, much like a painter carefully mixing pigments. The unique properties of each glass type – Cathedral, Opalescent, Antique, Streaky – are carefully considered to achieve the desired visual and luminous effects, influencing the mood and atmosphere of the final artwork. This often involves sourcing rare or specialty glass to achieve a particular artistic vision.

- Cutting & Shaping: The selected glass sheets are then meticulously cut to match the cutline pattern's exact shapes. This requires extraordinary skill, precision, and specialized tools. Glass cutters score the surface, creating a controlled fracture point, and then the glass is broken along that score with a swift, controlled movement. Small, curved cuts, or "grozing" (using grozing pliers), are often necessary to refine the edges and achieve the perfect fit, especially for intricate designs. This is a painstaking process that requires both experience and patience to minimize waste, ensure clean breaks, and achieve edges that will fit snugly within the came or foil, often involving precise grinding to perfect the fit and ensure smooth, safe edges.

- Assembly: The individual glass pieces are then carefully assembled, following the precise layout of the cartoon. In the traditional leading method, they are fitted snugly into the channels of H-shaped lead came, which acts as both structural support and the defining lines of the artwork. In the copper foil method, each piece is meticulously wrapped in adhesive-backed copper foil, which is then burnished smooth with a fid or burnishing tool to ensure maximum adhesion and a perfect, bubble-free seal. This gradual process slowly brings the design to life, transforming disparate shards into a coherent, luminous image, a true testament to patience and vision, often pinned to a workbench for stability.

- Soldering & Sealing: Finally, the entire panel is soldered together at all the joints, creating a strong, unified metallic grid that holds the artwork securely. For leaded work, a crucial and often-underestimated step is cementing – applying a waterproof putty or cement (a mix of linseed oil, whiting, and lampblack) meticulously under the lead flanges. This seals the panel against weather, prevents rattling of the glass, and significantly strengthens the entire piece, adding essential rigidity and ensuring its longevity, particularly for outdoor installations. For foiled work, a chemical sealant or grout is often applied to achieve similar waterproofing and structural stability. The piece is then thoroughly cleaned and polished, prepared for its ultimate installation, ready to tell its story in light, often involving applying a patina to the solder lines to achieve a desired finish.

It’s a process that demands patience, an eye for detail, a deep understanding of materials, and a commitment to precision, truly embodying the spirit of artisanal craft. Now, let’s explore the primary techniques in more detail.

Techniques & Craftsmanship: The Art of Light and Lead

Understanding the techniques involved really helps you appreciate the skill and patience behind each piece. It's not just cutting glass; it's a careful dance between design, material, and execution, requiring a deep understanding of both artistry and craft. If you're interested in what is design in art in a practical sense, this is a prime example of how conceptual planning meets meticulous handiwork, transforming raw materials into luminous works of art.

The Essential Tools of the Trade

Before diving into the techniques, it's worth a quick look at the arsenal of tools a stained glass artist employs. Each tool plays a crucial role in transforming raw materials into luminous art, demanding precision and a steady hand. Mastery of these tools is as important as the artistic vision itself:

Tool | Purpose | Usage Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Glass Cutter | Scores the surface of the glass, creating a weak point for breaking. | Can be pistol-grip or pencil-grip; typically features a carbide wheel for precision and durability, requiring light pressure. |

| Grozing Pliers | Nips off small unwanted bits of glass, refining edges and curves. | Essential for achieving complex shapes and tight fits, allowing for fine adjustments to cut pieces. |

| Running Pliers | Applies even pressure along a score line to cleanly break glass. | Helps ensure smooth, controlled breaks, especially on straight lines, by applying leverage. |

| Soldering Iron | Heats solder to melt and join lead came or copper foil seams. | Available in various wattages (e.g., 80-100W for stained glass); the tip must be kept clean and tinned for optimal heat transfer and smooth solder flow. |

| Solder | Metal alloy (e.g., tin-lead, lead-free) used to bond sections. | Applied to heated joints, forms strong, permanent connections. Commonly 60/40 tin-lead or newer lead-free alloys. |

| Flux | Chemical agent that cleans metal surfaces, allowing solder to flow. | Applied before soldering; available in liquid or paste forms. Absolutely essential for a strong, clean bond by removing oxidation. |

| Lead Nipper | Cuts lead came precisely to length and angle. | Specifically designed for lead, featuring a unique jaw shape that prevents flattening or distortion of the H-channel. |

| Fid / Burnisher | Smooths copper foil onto glass edges for maximum adhesion. | A plastic or wooden tool for firm, even pressure, ensuring no air bubbles and a tight seal around the glass edge. |

| Safety Glasses | Protects eyes from glass shards, solder splashes, and flux fumes. | Absolutely essential for all cutting, grinding, and soldering tasks to prevent eye injury. |

| Grinder | Smooths and shapes glass edges (optional, but highly recommended). | Features a diamond-bit grinding head; prevents cuts, refines fit, and allows for intricate shaping and detail work. Often water-cooled. |

| Pattern Shears | Cuts out paper patterns with a small gap to account for lead/foil. | Essential for accurate sizing of glass pieces; the double blades cut a thin line (the 'kerf') representing the came/foil width. |

| Light Box | Illuminates the cartoon/pattern from below for precise glass placement. | Aids in seeing intricate details, identifying perfect glass pieces, and checking color choices when assembling. |

| Leading Vice | Holds the stained glass panel securely while working. | Provides stability and support during the assembly, soldering, and cementing phases, preventing movement and distortion. |

Traditional Leading Method

This is the classic technique, primarily used for larger windows, like those in cathedrals, and it’s a method that truly connects us to centuries of craft. It involves:

- Design & Cartoon: The process always begins with a vision. The artist creates a detailed, full-scale drawing, traditionally called a cartoon, which is the blueprint for the entire piece. This cartoon meticulously details every individual piece of glass, its color, and the exact lines where the lead came will eventually run. From this, precise paper patterns are cut, often using specialized pattern shears that remove a tiny sliver of paper to account for the thickness of the lead came itself – this sliver is known as the 'cutline allowance' or 'kerf'. Sometimes, details are painted directly onto the cartoon using a technique called grisaille, which mimics the effects of painted glass. It's an intricate puzzle solved before a single piece of glass is cut, demanding immense precision and foresight in composition and design.

- Glass Cutting & Grozing: Each piece of colored glass is then meticulously cut to match the shapes outlined in the cutline pattern. This isn't just a simple snap! Special glass cutters score the surface, creating a controlled fracture point, and then the glass is broken along that score with a swift, controlled movement. Small, curved cuts, or "grozing" (using grozing pliers), are often necessary to refine the edges and ensure a perfect fit, a painstaking process that requires both skill and patience to minimize waste and achieve edges that will fit snugly within the came.

- Leading Up: This is where the magic really starts to take shape. The cut glass pieces are carefully fitted into the channels of H-shaped lead came, following the cartoon. Various profiles of lead came (flat, round, or U-shaped for edges, and differing widths) are chosen to suit the design, influencing both structural integrity and aesthetic line work. The lead acts as both the structural framework and the defining lines of the artwork. Pieces are assembled section by section, like a complex jigsaw puzzle, gradually revealing the full design, often pinned to a workbench to maintain alignment.

- Soldering: Once all the glass pieces are in place within the lead came, the joints where lead lines meet are meticulously soldered together using a hot soldering iron. This creates a strong, unified metallic grid that holds the entire panel together, ensuring its structural integrity. It's a delicate balance of heat and precision to get a clean, secure bond without cracking the surrounding glass, often requiring flux to ensure proper solder flow.

- Cementing & Finishing: Finally, a waterproof putty or cement (often a mix of linseed oil, whiting, and lampblack) is worked thoroughly under the lead flanges using a specialized cementing tool. This crucial step seals the panel against weather, prevents the glass from rattling, and significantly strengthens the entire piece, adding essential rigidity and ensuring its longevity, especially for external installations. The excess cement is then meticulously cleaned off, revealing the newly robust and luminous artwork, ready for its ultimate installation.

Copper Foil (Tiffany Method)

Developed by Louis Comfort Tiffany (and sometimes attributed to his contemporaries, but he certainly popularized it in the late 19th century), the copper foil method offers a world of intricate possibilities, allowing for a level of detail and three-dimensionality that traditional leading struggled to achieve. Instead of rigid lead came, this technique uses thin, adhesive-backed strips of copper foil (typically 7/32" or 1/4" wide, but available in various sizes and even colors like black-backed or silver-backed) wrapped meticulously around the edges of each individual glass piece. This foil is then carefully burnished smooth with a fid (a plastic or wooden tool) to ensure maximum adhesion and a perfect, bubble-free seal, creating a continuous metallic edge on each piece of glass. The foiled pieces are then arranged on the pattern, and all the copper seams are meticulously soldered together using a hot iron and flux, creating a continuous, strong, and relatively fine metallic bead that holds the artwork together. Artists can choose different solder finishes – natural silver (which is the default tin-lead or lead-free color), copper patina, or black patina – to complement the glass colors and achieve a desired aesthetic effect, further influencing the visual weight of the lines. This method allows for much finer details, smaller and more unusually shaped pieces of glass, and is particularly ideal for creating three-dimensional forms like lampshades, jewelry boxes, sculptural objects, and suncatchers, where the flexibility and strength of the solder joint are paramount. The resulting lines are significantly thinner than lead came, giving the piece a lighter, more delicate appearance, making it perfect for intricate organic designs.

Comparison of Techniques

Feature | Traditional Leading Method | Copper Foil (Tiffany Method) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Use | Large windows, architectural panels | Lamps, smaller panels, sculptural items |

| Bonding Agent | Lead came | Copper foil, then solder |

| Line Thickness | Thicker, more prominent lines | Finer, less visible lines |

| Detail Level | Suited for broader designs | Allows for intricate details and complex shapes |

| Flexibility | More rigid, less adaptable to curves | More flexible, ideal for 3D forms |

| Historical Era | Medieval to present | Late 19th century to present |

Dalle de Verre: Concrete and Chunks of Color

While traditional leading and copper foil dominate the stained glass landscape, there's another powerful, chunky, and utterly mesmerising technique called Dalle de Verre, or "slab glass." Originating in France in the early 20th century, particularly after World War I, this method involves using impressively thick, irregular pieces of colored glass – sometimes up to an inch or even more in thickness. These hefty glass chunks, or "dalles," are then strategically chipped, fractured, or faceted with a specialized hammer or a dalle cutter (a specialized tool to break thick glass) to create rough, light-refracting edges. The chipped dalles are then carefully arranged into a pre-designed pattern, often supported by a temporary wooden or metal frame, and set into a matrix of translucent concrete, cement, or epoxy resin, rather than the thinner lead or copper. The result? Windows and panels with an incredibly vibrant, almost gemstone-like quality, where the thick glass refracts and scatters light in a totally different, more intense and shimmering way than thinner sheet glass. The rough, chipped edges of the dalles often create a glittering, almost effervescent effect as light catches them, a truly unique textural and luminous experience that adds depth and dynamism. It’s a bold, robust, and incredibly durable technique that allows for dramatic, often abstract, designs, perfect for large-scale architectural projects requiring strong, durable panels, such as church walls, public building facades, and mausoleums. The concrete or resin matrix itself often forms part of the aesthetic, creating a powerful, sculptural feel that complements the raw beauty of the thick glass.

Painting and Staining Glass: Adding Detail and Hue

Sometimes, the inherent color of the glass itself isn't enough to capture the desired detail or nuance, especially for figurative work or subtle gradations. This is where the art of painting and true 'staining' comes in. It's important to distinguish between two distinct but complementary techniques that have been crucial for centuries in expanding the artistic possibilities of the medium:

- Glass Painting: This involves applying specialized glass paints or enamels onto the colored glass pieces. These paints are typically finely ground glass particles mixed with metallic oxides and a binder (like gum arabic or turpentine or water). Details like faces, hands, hair, drapery, or intricate patterns are meticulously applied to the glass surface, almost like miniature paintings on glass. Techniques like grisaille (a monochromatic, often black or brown, paint applied in washes and layers to create shading, depth, and three-dimensional effects, mimicking sculpture) and tracing lines (fine, dark lines used to outline figures and details, much like ink in a drawing, providing definition) are commonly employed. The painted pieces are then fired in a kiln at high temperatures (typically around 1200-1400°F or 650-760°C), which permanently fuses the paint to the glass surface, creating durable and intricate imagery that won't fade or scratch. This technique is absolutely essential for adding depth, shading, and fine lines that cannot be achieved by cutting glass alone, allowing for a level of figurative detail that distinguishes much of early stained glass and even modern narrative works.

- Silver Staining: This is a truly remarkable chemical process, and it was a groundbreaking innovation, particularly in the medieval period, appearing around the early 14th century! A compound of silver salts (typically silver nitrate or silver chloride) is applied to the back (exterior) surface of the glass and then fired in a kiln at a relatively lower temperature than glass paint. The silver ions penetrate the surface of the glass, and through a chemical reaction, produce a glorious range of translucent yellow to amber tones, depending on the silver compound used, the concentration, and the firing temperature and duration. This meant that a single piece of clear glass could suddenly contain multiple colors (its inherent color plus the new yellow/amber tones), greatly expanding the artist's palette and enabling stunning effects, particularly in medieval times when colored glass was more limited and costly. It allowed for the depiction of golden halos, rich hair, or illuminated texts without needing separate pieces of yellow glass. It’s fascinating how a touch of chemistry can unlock such artistic potential, allowing for nuanced shifts in color on a single pane, often giving the impression of gold without the expense, and adding a luminous warmth that enhances the surrounding hues. This innovation dramatically changed the aesthetic possibilities of stained glass, adding a new dimension of light and color.

More Than Just Windows: The Significance of Stained Glass

I think what makes stained glass truly significant isn't just its beauty, but its profound ability to transform space and emotion. It's an art form that demands interaction with its environment, a truly living medium.

Storytelling Through Light: Narratives and Symbolism

As mentioned, historically, especially in medieval cathedrals, stained glass was the ultimate visual bible, depicting narratives from scripture, lives of saints, and theological parables. It was a potent tool for religious instruction and emotional connection, making complex stories accessible to a largely illiterate populace, often referred to as the "Bible of the Poor." These luminous narratives didn't just decorate; they educated and inspired, transforming the church interior into a sacred picture book. Today, its storytelling capacity has broadened immensely. It can tell any story – personal, universal, historical, or purely abstract – imbued with rich symbolism through specific imagery (e.g., a dove for peace, a lion for courage, a rising sun for hope), and even the overall composition and color choices. Each pane can be a word, a phrase, a chapter in a much larger, luminous book, inviting contemplation and interpretation, a narrative constantly reimagined by the shifting light. Contemporary artists often use the medium to explore themes of identity, social justice, environmental concerns, or purely aesthetic principles, demonstrating its enduring narrative power. Whether depicting historical events, personal journeys, or abstract concepts, stained glass offers a unique canvas for narrative expression.

The Alchemy of Atmosphere: Light, Color, and Emotion

Ah, its undeniable superpower! Stained glass doesn't just reflect light; it filters it, colors it, and sculpts it, transforming mundane daylight into an almost mystical experience. A room with stained glass feels profoundly different, imbued with a unique aura. The light shifts throughout the day, constantly changing the mood and appearance of the artwork itself – a living, breathing painting that interacts with its environment in a way few other art forms can. Imagine the subtle transitions from dawn to dusk, painting the floor in a kaleidoscope of hues that fade and intensify with every passing cloud. It's truly dynamic, a constant play of illumination.

The interplay of specific colors also profoundly influences mood and contemplation, acting as a silent language of the soul. This is where color psychology truly comes into its own, guiding the emotional and spiritual experience of the viewer:

- Blue: Often associated with heaven, tranquility, peace, contemplation, and wisdom. Think of the deep, almost palpable blues of Chartres Cathedral, instantly evoking a sense of divine serenity and endless skies, creating an almost otherworldly atmosphere.

- Red: Symbolizes passion, sacrifice, divine love, energy, and martyrdom. Used sparingly, it can create powerful focal points that draw the eye and stir strong emotions, often signifying fervent spiritual intensity or the blood of Christ, demanding attention.

- Yellow/Gold: Represents divine light, glory, revelation, enlightenment, and wisdom. Historically, it also simulated the preciousness of gold, particularly in depictions of halos or heavenly scenes, bathing the space in a warm, ethereal glow.

- Green: Evokes nature, growth, renewal, hope, and earthly paradise. It offers a calming counterpoint to more intense colors, connecting the spiritual realm to the natural world, often used for landscapes or foliage within a scene.

- Violet/Purple: Signifies spirituality, penance, mourning, and royalty. Its rarity in medieval dyes often made it associated with imperial power and divine majesty, lending an air of solemnity and grandeur.

- White/Clear: For purity, truth, innocence, and often used to represent divinity, intense brightness, or to provide contrast, allowing the vibrant colors to truly sing. It acts as a visual breath, highlighting the saturated hues around it and creating focal points of brilliant light.

- Brown/Earth Tones: Symbolize humility, the earth, and human nature, often used for figures or architectural details, grounding the composition and providing a sense of stability and realism.

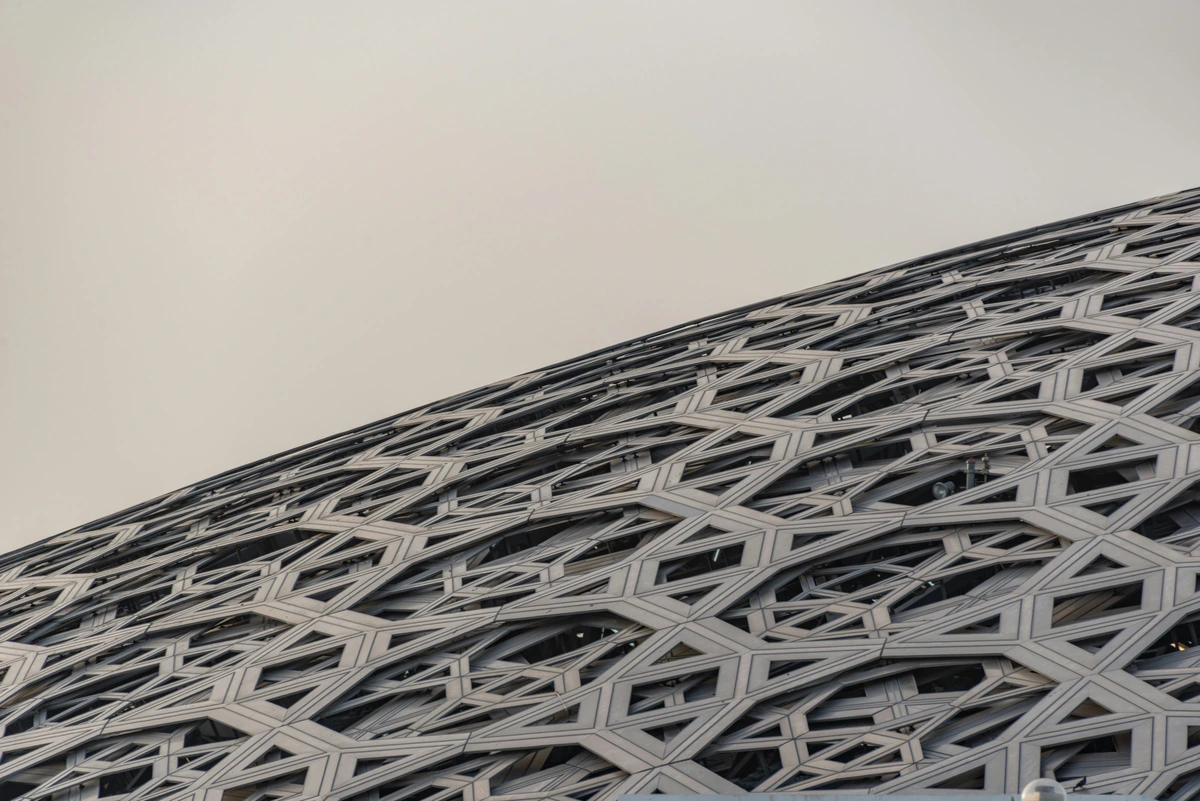

Architectural Integration: Art as Structure

Unlike a painting on a wall or a sculpture on a pedestal, stained glass is almost always an integral part of the architecture itself. It functions not merely as decoration, but as a load-bearing or light-filtering component that fundamentally alters the character and function of a space. It blurss the lines between art and building in the most profound way. It's not just in the building; it is part of the building, shaping its very fabric and experience. From ancient cathedrals where windows define the interior space, to modern architectural marvels like the Louvre Abu Dhabi with its intricate dome filtering light, stained glass becomes an inseparable element, a dialogue between structure and luminosity. Think of its use in grand train stations (like the stunning stained glass dome in the Palace of Catalan Music in Barcelona), opulent hotels, and even modernist churches such as the Coventry Cathedral or the Wieskirche, where the glass often takes on abstract forms, defining and elevating the space and playing with scale and light in entirely new ways. Its capacity to transform mundane walls into luminous membranes of color and light is unparalleled.

Regional Styles and Influence: A Global Tapestry of Light

It's always fascinating to see how local cultures and artistic traditions shape a universal medium. Stained glass is no exception.

Across different cultures and historical periods, distinct regional styles of stained glass emerged, reflecting local aesthetics, available materials, and evolving theological or artistic priorities. From the dense, jewel-like compositions of French Gothic cathedrals, often prioritizing deep blues and reds to create a mystical darkness, to the more narrative and illustrative panels of English medieval work, which frequently featured lighter backgrounds and more detailed figurative scenes, these variations highlight the incredible versatility and adaptability of the medium. We can also see distinct styles in the geometric patterns of Islamic art glass, the vibrant modernism of German Expressionist glass (like the abstract works of Johannes Schreiter or Georg Meistermann), or the unique organic forms of American Art Nouveau glass, particularly those by Louis Comfort Tiffany and his contemporaries. Exploring these differences is like tracing a luminous thread through the history of art, revealing how culture and context shape artistic expression, from the spiritual narratives of medieval Europe to the secular beauty of modern architectural statements.

Preservation of Craft and Legacy: Enduring Artisanship and Conservation

Beyond its immediate aesthetic and spiritual impact, stained glass also represents a continuous lineage of incredible craftsmanship. It's a testament to the enduring human desire to create beauty and meaning through demanding, precise artisanal skills. Each restored window, each new commission, carries forward centuries of tradition, knowledge, and artistic legacy, connecting us directly to the hands and minds of artisans from across time. The dedication required to master this craft ensures its survival and evolution, supported by a growing field of stained glass conservation dedicated to preserving these luminous treasures for future generations. This field addresses the unique challenges of aging lead (which can sag or crack due to 'lead fatigue'), deteriorating cement, fragile painted details, and the effects of environmental pollution or vandalism, ensuring the survival of this delicate art. Conservators meticulously analyze historical techniques and materials to ensure repairs are sympathetic and reversible, maintaining the integrity and authenticity of each piece.

Stained Glass in the Modern World

It would be a mistake to relegate stained glass to the dusty annals of history. This is an art form that continues to thrive and evolve, adapting to contemporary aesthetics and technological advancements.

While we might associate it predominantly with ancient churches and grand historical periods, stained glass is far from a relic. It's a vibrant, evolving art form that continues to captivate and inspire. Contemporary artists are passionately pushing its boundaries, experimenting with new techniques like fusing and slumping glass (melting multiple layers together to create sculptural forms), incorporating new materials, and exploring themes that range from the deeply personal to pressing global issues.

You’ll find modern stained glass not just in homes and galleries, but also in striking public art installations, corporate headquarters, and even as dynamic, standalone sculptures. Contemporary artists are passionately pushing its boundaries, experimenting with new techniques like fusing and slumping glass (melting multiple layers together to create sculptural forms), incorporating new materials, and exploring themes that range from the deeply personal to pressing global issues. It's still being used to tell stories, just perhaps different stories than those of the saints – stories of identity, nature, urban life, or pure abstract contemplation. The beauty of it, for me, is its endless capacity for reinvention.

Famous Stained Glass Artists (Beyond Tiffany)

While Louis Comfort Tiffany undeniably brought stained glass into a new era, a pantheon of other talented artists, both historical and contemporary, have left indelible marks on the medium. In the medieval period, the master glaziers were often anonymous, their individual genius subsumed by the collaborative workshop. However, as the art evolved, so did the recognition of individual vision.

Post-Tiffany, and particularly in the 20th and 21st centuries, artists like Marc Chagall brought a deeply personal, often dreamlike narrative quality to his monumental windows in places like the United Nations Headquarters, Fraumünster in Zurich, and Reims Cathedral. His work often transcended traditional religious iconography, imbuing spaces with vibrant, emotional storytelling. Other notable figures include Frank Lloyd Wright, who integrated stained glass as a fundamental architectural element in his Prairie School homes, often with abstract, geometric designs; John La Farge, an American contemporary of Tiffany who developed new opalescent glass techniques; Johannes Schreiter, known for his abstract, architectural glass, particularly in post-war Germany; and Judith Schaechter, who pushes the boundaries with her intricate, often dark and narrative panels, challenging traditional notions of the medium with her unique contemporary voice. Contemporary artists continue to experiment with new materials and techniques, ensuring that stained glass remains a dynamic and evolving art form, far from being confined to historical contexts. Indeed, its integration into various art movements of the 21st century speaks volumes about its enduring relevance and adaptability.

If you're ever near a contemporary art space or a well-curated modern museum, keep an eye out. You might be surprised at the innovative ways artists are using this ancient medium, breaking free from traditional constraints. It's a testament to its enduring versatility and charm, a powerful dialogue between centuries of tradition and the restless spirit of contemporary abstract art.

Frequently Asked Questions About Stained Glass Art

It's natural to have questions about an art form with such a rich history and intricate process. Here are a few I often encounter, hopefully shedding more light on this luminous craft:

Q1: Is stained glass always made with lead?

Not always! While lead came is the traditional method and remains very popular, it's certainly not the only option. The copper foil method (popularized by Tiffany in the late 19th century) uses thin, adhesive-backed copper strips, allowing for much finer lines, more intricate designs, and the creation of three-dimensional objects like lampshades. Furthermore, modern artists sometimes use other metal cames like zinc, brass, or even innovative assembly methods involving adhesives, silicone, or various framing techniques for a contemporary aesthetic, especially for smaller decorative pieces or those designed to be lead-free for safety reasons. So while lead is classic, it's definitely not the exclusive medium anymore; the choice often depends on the desired aesthetic, structural requirements, and modern safety considerations.

Q2: How is the color put into stained glass?

The color is primarily an inherent part of the glass itself, achieved by adding various metallic oxides to the molten glass during its manufacturing process. For instance, cobalt yields brilliant blues, copper can create striking reds or rich greens, manganese produces purples, and gold can create a luxurious ruby red. These oxides introduce specific ions that selectively absorb and transmit different wavelengths of light. Additionally, details, shading, or specific hues can be added by applying specialized glass paints or enamels onto the surface of the colored glass. These painted pieces are then fired in a kiln at high temperatures, permanently fusing the paint to the glass, a process essential for figurative details like faces or drapery. Silver staining is another historical technique that chemically alters the surface of clear glass to produce yellow to amber tones.

Q3: Is stained glass difficult to maintain?

Generally, stained glass is surprisingly durable once properly installed, designed to last for centuries with proper care. Routine maintenance is quite low-key: regular, gentle cleaning with a soft, lint-free cloth and distilled water, perhaps with a very mild, non-abrasive soap for stubborn grime, is usually sufficient to keep it looking its best. The key is to always avoid harsh chemicals, ammonia-based cleaners, abrasive tools, or excessive scrubbing, as these can irreparably damage the glass, corrode the lead came, or strip away delicate painted details and patinas. Dusting regularly helps prevent build-up, ensuring the light can always pass through unimpeded. For older or very delicate pieces, especially those with painted details, professional inspection every few decades is highly recommended. This allows conservators to address potential issues like sagging lead (often referred to as 'lead fatigue'), cracked panes, deterioration of cementing putty, or structural fatigue before they become severe, ensuring the artwork's longevity. With conscientious care, stained glass is a remarkably resilient art form, far more so than its delicate appearance might suggest.

Q4: Can stained glass be abstract?

Absolutely! While traditional stained glass often depicted figurative religious scenes, modern artists widely embrace abstract designs, moving beyond explicit narratives to explore pure form, color, and light. The play of light and color through geometric shapes, organic forms, or non-representational patterns can be incredibly powerful, contemplative, and emotionally resonant. Think of the dynamic, vibrant compositions in many contemporary public art installations, where the abstract nature allows for universal interpretation. Just as abstract art explores meaning beyond direct representation, so too can abstract stained glass create profound experiences purely through its visual language.

Q5: What's the difference between stained glass and leaded glass?

Technically, stained glass refers specifically to glass that has been colored, either inherently during its manufacture or through painting/staining techniques. Leaded glass is a broader term for any glass panel assembled with lead came, regardless of whether the individual glass pieces are colored, clear, textured, or beveled. So, while most stained glass from traditional eras is also leaded glass (as lead came was the primary assembly method), not all leaded glass is stained glass. For example, a clear glass window with intricate geometric patterns held together by lead came would be leaded glass, but not necessarily stained glass.

Q6: What tools are needed to make stained glass?

If you're looking to dip your toes into this fascinating craft, you'll need a few essential tools to start your luminous journey. For either traditional leaded work or the copper foil method, you'll definitely want a glass cutter (a scoring tool, usually with a carbide wheel), grozing pliers (for nipping and shaping glass edges), running pliers (to break glass cleanly along score lines), a soldering iron, solder, flux (a chemical that helps solder flow), and, crucially, safety glasses and a designated cutting surface. For leaded work specifically, you'll also need lead came, lead nippers, a leading vice to hold the panel, and cementing tools. For copper foil, you'll obviously need copper foil itself, and a fid or burnisher to smooth it. It sounds like a lot, but you can often find beginner kits with the basics, and many communities offer workshops where tools are provided. You'll also likely want a glass grinder for refining edges and achieving precise fits.

Q7: Can I learn to make stained glass?

Absolutely! Stained glass is a skill that can be learned, and there are countless workshops, community college courses, online tutorials, and local studios offering classes available for beginners. While it certainly requires patience, precision, and a bit of a learning curve, the satisfaction of creating your own luminous artwork is immense. Many artists find it incredibly meditative and rewarding. I'd highly recommend starting with the copper foil method for smaller projects like suncatchers or jewelry boxes, as it's often more forgiving for beginners than traditional leading. Seek out local artisans; many are happy to share their knowledge and passion, and there's nothing quite like learning directly from a master craftsman!

Q8: What is the largest stained glass window in the world?

That's a fun question, and one that sparks much debate! While it's hard to definitively name the single largest due to varying criteria (surface area, height, artistic complexity), several monumental works stand out. The Resurrection Window by Max Ingrand at the Coventry Cathedral in England is famously enormous, measuring 70 feet high and 45 feet wide, and is a striking example of modern abstract stained glass. Another colossal contender for sheer scale is the Great East Window in York Minster, England, which is a massive 76 feet high and 32 feet wide, and dates back to the early 15th century, showcasing intricate medieval narrative. Additionally, the windows of Sainte-Chapelle in Paris, while not a single window, collectively represent an astonishing expanse of stained glass, forming virtual walls of light across its upper chapel, encompassing over 1,113 individual scenes. These monumental pieces truly demonstrate the incredible scale and ambition possible with stained glass, transforming entire architectural spaces into breathtaking light installations and acting as powerful visual narratives.

Q9: My stained glass has a crack, can it be repaired?

Yes, most stained glass pieces, even those with cracks, can be repaired! The feasibility and cost depend on the size and location of the crack, the type of glass, and the construction method. Minor cracks in foiled pieces can sometimes be patched with a thin bead of solder, but for more significant damage, especially in leaded panels, a professional conservator or stained glass artist will replace individual broken panes. This is a delicate process that often involves carefully dissecting the lead came or solder lines around the damaged piece, cutting a new one to match the original in color and texture, and then meticulously re-leading or re-foiling and soldering it back into the panel. While painstaking, it’s definitely possible to restore a cherished piece to its former glory and extend its lifespan significantly.

Q10: Are there different types of colored glass beyond what's mentioned?

Indeed! We touched upon Cathedral, Opalescent, Flashed, Antique, and Streaky glass earlier, but the world of art glass is vast and endlessly fascinating. You'll also encounter Wispy glass (a soft, semi-translucent streaky glass, often used for skies or misty effects), Mottled glass (opalescent glass with distinct, irregular patterns of more intense color), Iridescent glass (which has a thin metallic coating that creates a rainbow sheen on the surface), and even specialty glasses designed for specific optical effects, like hammered, rippled, or reamy textures that distort light in intriguing ways. There's also Drawn glass, which is pulled in sheets, and Rolled glass, which is flattened using rollers, each producing unique characteristics. Each type offers a unique way of interacting with light, providing artists with an almost infinite palette of textures, opacities, and hues to work with, each demanding a different approach and contributing a distinct character to the final piece. It's truly a universe of glass out there, waiting to be explored, and a skilled artist understands how to leverage the unique properties of each to achieve their vision!

Q11: What is thermal stress and how does it affect stained glass?

Thermal stress occurs when different parts of a stained glass panel expand and contract at different rates due to variations in temperature, or when the glass heats up or cools down too quickly. This can lead to cracks in the glass, especially in larger panels or those with many pieces joined together, as the materials (glass, lead, solder) all have slightly different expansion coefficients. While modern installation techniques and proper cementing help mitigate this, extreme temperature swings or direct, intense sunlight on one section while another remains cool can still pose a risk over time. It's a common factor conservators consider when evaluating older windows, as these subtle stresses can accumulate over decades, leading to structural fatigue and eventual cracking.

Q12: How long does it take to make a stained glass piece?