Art Nouveau vs. Art Deco: Unraveling the Iconic Differences in Modern Art & Design

Ever wondered about the elegant swirls of Art Nouveau versus the sleek lines of Art Deco? Join us as we curate a deep dive into these two influential artistic movements, dissecting their unique philosophies, styles, and enduring legacies.

Art Nouveau vs. Art Deco: The Ultimate Guide to Their Iconic Differences & Enduring Legacies

Ah, Art Nouveau and Art Deco. As a curator, and someone who's spent decades immersed in the nuances of artistic expression, I can tell you these two titans of design, often spoken of in the same breath and frequently confused, each possess a soul and a story utterly their own. I find myself constantly, gently, pulling people aside to highlight the nuanced—and sometimes glaring—distinctions that truly define these captivating periods. It’s a bit like comparing a wild, untamed garden, bursting with organic life and defiant growth, to a perfectly cut, gleaming diamond, precisely engineered for maximum sparkle; both breathtaking, yes, but each whispering an entirely different tale of aesthetics, purpose, and cultural zeitgeist. So, grab a coffee, let’s peel back the layers and truly understand what sets these magnificent movements apart, why their legacies still shape our visual world today, and how they laid the groundwork for so much of what we call modern. Think of this as your definitive guide, a journey into the heart of early modern art's most fascinating dialogue. You won't find a more comprehensive or engaging comparison, I promise.

The Flourish of Art Nouveau: Nature's Embrace and the Cult of Craftsmanship

Picture this: the late 19th century, right around 1890. The gears of the Industrial Revolution were grinding, spitting out identical objects, and frankly, people were getting a bit tired of it. There was this deep, almost primal, yearning for something else – something organic, something touched by human hands, a defiant rejection of the soulless uniformity of the machine. That, my friends, is the fertile ground from which Art Nouveau—French for 'New Art'—burst forth, a vibrant, almost rebellious, fluid movement generally accepted to span from 1890 to 1910, although its tendrils reached further. It wasn't just a style; it was a philosophy, a way of seeing the world. To dive even deeper into its origins, I often refer to our definitive guide to Art Nouveau movement.

At its heart, Art Nouveau was less a trend and more an artistic manifesto. It passionately advocated for art to permeate every corner of daily existence, dissolving the rigid boundaries between 'fine art' and 'applied art'—from the grandest architectural façade to the most delicate piece of jewelry, even down to a simple letter opener. This isn't just about pretty pictures; it’s about a total aesthetic experience. It’s often characterized by key features that, once you see them, you’ll spot everywhere:

- Rich Symbolism: Art Nouveau was deeply connected to the broader Symbolist movement in painting and literature. Designs were often infused with symbolic meaning, drawing from mythology, folklore, and the subconscious, adding layers of narrative and emotion. This wasn't just beauty; it was beauty with a message, often enigmatic and evocative, much like the hidden layers I explore in my own abstract pieces.

- Organic Forms and Flowing Lines: This is the absolute signature, the visual heartbeat of Art Nouveau. Imagine the graceful curve of a plant stem unfurling, the undulating movement of water, or the flowing locks of a mythical maiden caught in a breeze. We’re talking about sinuous, curvilinear lines, often dramatically elongated and described as the iconic 'whiplash' line—a dynamic, asymmetrical curve that seems to pulsate with life. These aren't just decorative flourishes; they are structural elements, mimicking natural forms like vines, flowers, insects, and yes, the famously flowing, often idealized, hair of women. There’s a distinct asymmetry and dynamism that feels almost alive, a rebellion against the rigid geometry and historical pastiche of earlier eras. It’s about line as an expressive, almost sentient force, a concept I explore often in my guide to understanding line in abstract art. It’s an art that breathes.

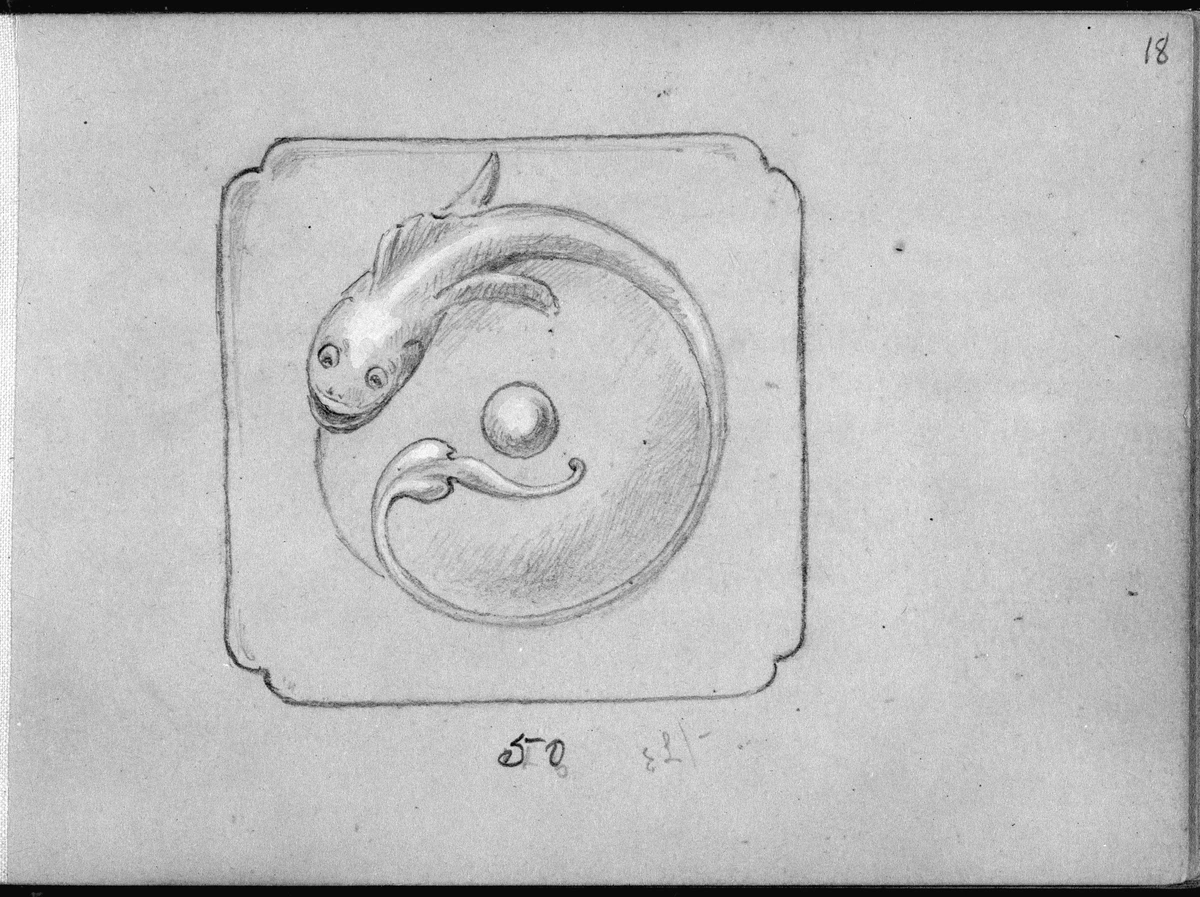

- Nature-Inspired Motifs: The natural world was its inexhaustible wellspring of inspiration, a direct antidote to the urban grime of the Industrial Revolution. Think lush lilies, delicate irises, proud peacocks, shimmering dragonflies, even exotic orchids, and the ethereal forms of water nymphs or mermaids. These weren't merely tacked-on decorations; they were fundamental to the very structure, rhythm, and ethos of the design. Each motif was imbued with a sense of growth, vitality, and often, symbolic meaning, creating a cohesive, living whole. You'll often find flowers with long, elegant stems, insects with delicate, translucent wings, and the sinuous forms of female figures, all intertwined in a harmonious, organic dance.

- Embracing the Handcrafted and the 'Total Work of Art': This was a direct, often impassioned, counter-argument to the impersonal, standardized output of the factory. There was a fierce emphasis on craftsmanship, a celebration of the artisan's skill, and a rejection of mechanical reproduction. The ideal was the Gesamtkunstwerk—the 'total work of art' (a concept championed by Richard Wagner, but fully embraced here)—where every single element of a building, interior, or object was meticulously designed in a unified, harmonious style. From the grand architectural facade to the smallest door handle, the stained glass to the furniture, the wallpaper to the jewelry, everything contributed to one immersive, aesthetic experience. It was a true testament to comprehensive understanding the elements of design in art, aiming for nothing less than a completely unified environment. Think of Victor Horta's Hôtel Tassel in Brussels, where the curving lines of the staircase, the ironwork, and the wall frescoes all flow together to create a single, organic, and breathtaking statement.

Where Art Nouveau Flourished: A Global Embrace

While we might immediately think of paintings and sculptures, Art Nouveau truly found its most glorious expression in the applied arts and architecture. This movement wasn't confined to canvases; it was about shaping entire environments, democratizing art, and infusing beauty into daily life. Think of the iconic, flowing ironwork of the Paris Métro entrances, designed by Hector Guimard; the ethereal, intricate jewelry of René Lalique, often featuring insects, mythical figures, and incredibly innovative glass techniques (our ultimate guide to Art Nouveau jewelry is a must-read if this piques your interest); or the stunning, iridescent glasswork of Louis Comfort Tiffany, particularly his lamps and stained-glass windows. From graphic design, such as Alphonse Mucha’s exquisite posters celebrating the female form and natural elements, to furniture, textiles, and everyday objects, Art Nouveau sought to beautify every aspect of life. Its ambition knew no bounds. Its global presence was manifested through diverse regional interpretations, each adding its unique flavor to the core principles. And, of course, the architectural masterpieces that epitomize the style truly changed cityscapes and interior spaces:

Casa Batlló in Barcelona, designed by the inimitable Antoni Gaudí, is a fantastic, almost fantastical, example, with its undulating forms, bone-like columns, and scaled, dragon-esque roof. It feels like it grew out of the earth rather than being built. And closer to my heart, the elegance of the Vienna Secession building is a profound testament to the movement's ambition to create a 'total work of art,' where every detail contributes to a unified aesthetic vision. We also can't forget Charles Rennie Mackintosh's Glasgow School of Art, where his elegant linearity and subtle use of organic motifs created a distinctly Scottish flavor of the movement, often referred to as the 'Glasgow Style.' Art Nouveau truly embraced regional interpretations, allowing its core principles to be filtered through local traditions and tastes, leading to distinct variations like 'Jugendstil' in Germany and 'Stile Liberty' in Italy. It was a truly global phenomenon, albeit with many delightful variations.

Influential Art Nouveau Publications and Exhibitions

Beyond individual artists and architectural marvels, the dissemination of Art Nouveau's aesthetic was greatly aided by influential publications and international exhibitions. Magazines like Jugend in Germany (from which Jugendstil gets its name) and Ver Sacrum of the Vienna Secession played a crucial role in shaping public taste and promoting the movement's ideals. These journals featured stunning graphic design, illustrations, and theoretical texts, reaching a wide audience and solidifying Art Nouveau's intellectual foundations. International expositions, such as the Paris Exposition Universelle of 1900, also served as vital platforms, showcasing the latest Art Nouveau designs in architecture, furniture, and decorative arts to a global audience, further solidifying its international reach and impact on the burgeoning modern world.

Key Figures of Art Nouveau: Beyond the Brushstroke

While Art Nouveau permeated every aspect of design, certain artists became synonymous with its defining aesthetic. It's not just about what they made, but how they thought about art's role in society:

- Alphonse Mucha (Czech, 1860–1939): The undisputed master of the Art Nouveau poster. His opulent, swirling compositions, often featuring idealized women in flowing robes, surrounded by natural elements and intricate patterns, defined the look of turn-of-the-century advertising. His theatrical posters for Sarah Bernhardt are legendary, turning commercial art into exquisite fine art.

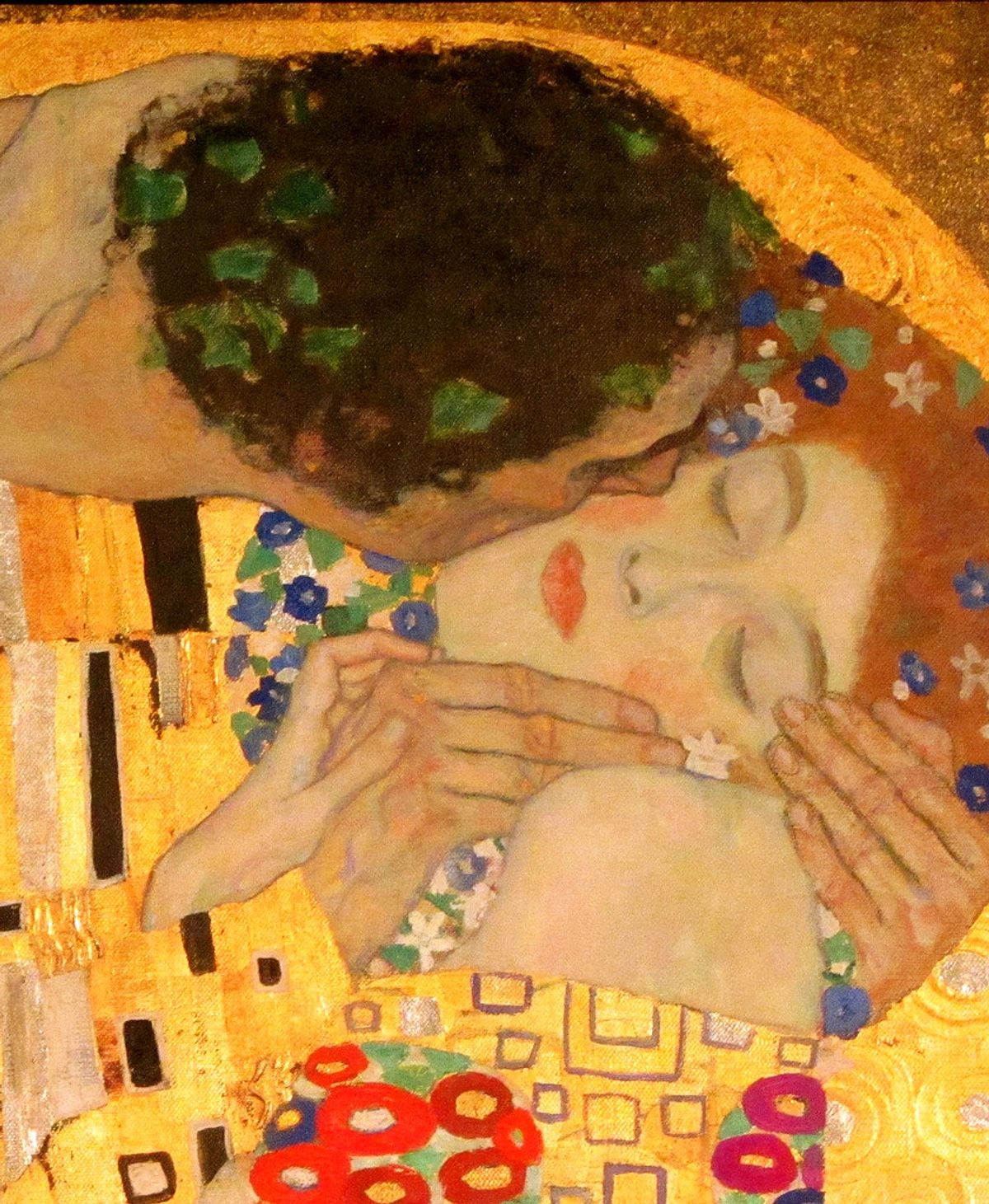

- Gustav Klimt (Austrian, 1862–1918): As a prominent member of the Vienna Secession, Klimt's work, particularly his 'Golden Phase' paintings like 'The Kiss' and 'Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I,' blend rich symbolism with dazzling gold leaf and intricate decorative patterns. His figures are often enigmatic, sensual, and imbued with a deeply psychological quality, reflecting the Symbolist undercurrents of the movement.

- Hector Guimard (French, 1867–1942): The architect responsible for the iconic Art Nouveau entrances of the Paris Métro. His cast-iron designs, with their fluid, organic lines, glass canopies, and distinct typography, brought the movement into the everyday urban landscape, making public transport an artistic experience. He saw each station as a complete artistic statement, from the intricate ironwork mimicking plant forms to the unique lettering of the signage. His work truly brought 'art for all' to life in the urban sphere, transforming mundane utility into sculptural beauty.

- René Lalique (French, 1860–1945): A jeweler and glassmaker who elevated the applied arts to new heights. His pieces, often featuring mythological creatures, insects (like dragonflies), and the female form in exquisitely crafted enamel, glass, and semi-precious stones, are masterpieces of delicate artistry and innovative material use. He saw jewelry not just as ornamentation but as wearable sculpture.

- Victor Horta (Belgian, 1861–1947): A pioneering architect whose private residences in Brussels (like Hôtel Tassel, Hôtel Solvay, and his own Horta House) are considered seminal works of Art Nouveau architecture. His use of exposed ironwork, flowing 'whiplash' lines in staircases, murals, and mosaics, and his revolutionary open floor plans created truly integrated, luminous, and organic living spaces.

- Charles Rennie Mackintosh (Scottish, 1868–1928): A key figure in the Glasgow School, Mackintosh developed a more rectilinear, yet still highly symbolic and nature-inspired, form of Art Nouveau. His distinctive style, often referred to as the 'Glasgow Style,' is characterized by elegant proportions, geometric rigor softened by subtle curves, and motifs like the 'Glasgow Rose' and elongated female figures. His work at the Glasgow School of Art, from its robust exterior to its exquisitely detailed interiors, is a testament to his unique vision, blending traditional Scottish elements with the 'New Art' ethos, creating spaces that are both functional and profoundly spiritual.

Artists like Gustav Klimt, with his shimmering gold leaf, intricate patterns, and deeply symbolic figures, are intrinsically linked with the Vienna Secession, a particularly radical and influential branch of Art Nouveau in Austria. His work, like 'The Kiss' (which, if you haven't seen it, is a true masterpiece that still gives me chills), perfectly encapsulates the decorative, emotional, and symbolic qualities of the movement, particularly in its Austrian iteration. You can explore more of his incredible work in our ultimate guide to Gustav Klimt.

Art Deco: The Roaring Twenties' Modernity and the Celebration of the Machine Age

Now, let's hit the fast-forward button. We've emerged from the Great War, and the world is exhaling, ready for a new chapter. The trauma of conflict gives way to an explosion of optimism, technological wonder, and a craving for glamour and escapism. This is where Art Deco makes its grand entrance, a style that didn't just flourish but dominated from the vibrant 1920s into the late 1930s—a period we fondly remember as the 'Roaring Twenties,' the 'Jazz Age,' and the 'Machine Age.' It’s the visual soundtrack to an era of unprecedented economic prosperity (for some), flappers, widespread social change, and newfound freedoms. For those who want to really immerse themselves, our ultimate guide to Art Deco movement is an essential read, but for now, let's consider how this era, scarred by war, was paradoxically eager for exuberance and a definitive break from the past.

Art Deco, in many ways, was a deliberate, almost audacious, break from its predecessor. Where Art Nouveau whispered secrets from the natural world with organic fluidity, Art Deco shouted from the rooftops of skyscrapers, celebrating the machine age, technological advancement, and the electrifying pulse of urban life. It's truly a testament to how rapidly artistic sensibilities can evolve, shifting from a pastoral dream to a metropolitan marvel in a blink of an eye. Its hallmarks are unmistakable and speak volumes about its era:

- Geometric Shapes and Clean, Streamlined Lines: This is the antithesis of Art Nouveau's organic flow. We bid adieu to undulating curves and embrace bold symmetry, rectilinear forms, and crisp, sharp angles. Imagine zigzags, chevrons, dynamic sunbursts, and majestic tiered shapes reminiscent of ancient Ziggurats or the stepped profiles of new skyscrapers. This focus on geometry often reflects direct influences from avant-garde movements like Cubism, with its fragmented perspectives, and particularly Futurism, which celebrated precision, speed, and the dynamism of modern life. It's a style that really shows the symbolism of geometric shapes in abstract art, stripping away excessive ornamentation to reveal a sleek, powerful aesthetic that felt utterly modern and forward-looking. This geometric rigor often lends itself to the structured, vibrant energy I try to capture in some of my own more linear works, albeit with a contemporary twist.

- Glamour, Luxury, and Modern Opulence: This was the quintessential style of the flapper, the magnificent ocean liner (think the SS Normandie), the grand hotel, and the soaring skyscraper. Art Deco didn't just suggest luxury; it exuded it from every polished surface and gleaming detail. It spoke of sophistication, an almost celebratory materialism, and a desire for all things opulent and modern after the austerity of war. It was the visual language of the Jazz Age, embodying a sense of carefree indulgence, progress, and a bold embrace of a hedonistic lifestyle. Think grand entrances, lavish interiors, dazzling fashion, and the rise of Hollywood glamor. Our exploration of Art Deco's enduring influence on modern fashion gives even more context, highlighting its impact on silhouettes, jewelry, and accessories, which to me, is a perfect illustration of art's journey from galleries to everyday life.

- Eclectic and Exotic Inspirations: While unequivocally modern in its final form, Art Deco was a cultural magpie, drawing heavily from a wonderfully diverse array of global sources. The discovery of Tutankhamun's tomb in 1922, for instance, sparked a pervasive fascination with Ancient Egyptian art, which lent itself perfectly to geometric patterns, stylized figures, and monumental scale. Aztec and Mayan motifs, African tribal art (exploring the influence of African art on modernism is fascinating), Russian Constructivism, and even the machine aesthetic itself, all contributed to its rich and often surprising visual vocabulary. It's a blend that, on paper, sounds contradictory, but in practice, was revolutionary and forged a distinctly new global style. This ability to synthesize disparate influences into something fresh is something I deeply admire, and often try to emulate in my own practice.

- Embracing New Materials and Industrial Techniques: This movement didn't shy away from the industrial; it celebrated it with unbridled enthusiasm. Art Deco eagerly utilized modern materials like chrome, gleaming stainless steel, plate glass, sleek lacquer, and the then-revolutionary Bakelite (an early plastic, mind you!). These were often combined with luxurious, traditional finishes and exotic woods (like ebony and zebrawood), sharkskin, or even ivory and jade, creating a striking contrast between the machine-made and the handcrafted, the industrial and the opulent. It was a forward-looking aesthetic that perfectly matched the era's technological advancements, turning factories into sources of artistic inspiration and new materials into mediums for luxury. This embrace of industrial aesthetics and new materials, for me, is a powerful precursor to how contemporary artists approach unconventional mediums today.

Art Deco and the World's Fairs: Global Showcases of Modernity

One of the most potent vehicles for Art Deco's global dissemination was undoubtedly the international exposition, or World's Fair. These grand events served as spectacular showcases for the latest in art, design, architecture, and technological innovation. The Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes in Paris in 1925, from which Art Deco gets its very name, was a seminal moment, presenting a unified vision of modern luxury and functional design to millions of visitors. Subsequent fairs, such as the 1933 Chicago 'Century of Progress' Exposition and the 1939 New York World's Fair, continued to propagate the style's sleek, optimistic aesthetic worldwide. These expositions not only influenced public taste but also fostered a sense of global interconnectedness, proving that modern design could transcend national borders and speak a universal language of progress and sophistication.

Where Art Deco Sparkled: From Skyscrapers to Silverware

Art Deco's influence was incredibly pervasive; it truly permeated every facet of design, touching everything from fashion and jewelry to furniture, vibrant posters, and perhaps most spectacularly, architecture. The magnificent Chrysler Building in New York City, with its gleaming gargoyles and sunburst crown, stands as perhaps its most iconic architectural representation, a true temple to commerce and modernity. But its reach was far wider: countless structures, stylish interiors, industrial designs, and even everyday objects—from radios and telephones to toasters and streamlined automobiles—bore its distinctive, luxurious mark. It wasn't just about grand statements; it was about bringing sophistication to the mundane. You can see its lasting impact in our guide to Art Deco's influence on modern design and architecture.

Key Figures of Art Deco: The Architects of Modern Glamour

While Art Deco often celebrated anonymity in design (the machine aesthetic, after all), many brilliant individuals shaped its iconic look, creating pieces that are still coveted today:

- Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann (French, 1879–1933): The quintessential Art Deco furniture designer, known for his exquisite, opulent creations using rare woods like macassar ebony and amboyna, often inlaid with ivory, tortoiseshell, or shagreen. His work epitomized the luxurious, high-end side of Art Deco, making furniture into objets d'art rather than mere utilitarian pieces, a true testament to the era's celebration of craftsmanship and refined taste.

- Tamara de Lempicka (Polish, 1898–1980): A painter whose stylized, glamorous portraits of aristocrats and flappers perfectly captured the sophistication and sensuality of the Jazz Age. Her crisp, almost sculptural lines, bold, often saturated colors, and dramatic lighting are instantly recognizable and deeply embody the Art Deco aesthetic in fine art. Her powerful, independent female figures became icons of a new era of freedom and modernity.

- René Lalique (French, 1860–1945): While also an Art Nouveau master, Lalique seamlessly transitioned into Art Deco, adapting his glassmaking genius to the new geometric aesthetic. His frosted glass vases, car mascots, and architectural glass panels, often featuring stylized figures, flora, and fauna, became icons of Art Deco luxury.

- Erte (Romain de Tirtoff, Russian-French, 1892–1990): A prolific artist and designer, Erte defined much of the fashion illustration and graphic design of the Art Deco era. His elegant, elongated figures, intricate costumes, and sophisticated compositions graced magazine covers (famously Harper's Bazaar), theater sets, and fashion plates, making him a true arbiter of the period's visual style. His work extended into sculpture and jewelry, showcasing his mastery across multiple artistic disciplines.

- Raymond Hood (American, 1881–1934): A prominent architect responsible for some of New York's most iconic Art Deco skyscrapers, including the American Radiator Building and, notably, a significant role in the design of Rockefeller Center. His buildings combined powerful massing with intricate, often metallic, decorative details.

- William Van Alen (American, 1883–1954): The architect of the magnificent Chrysler Building. His masterpiece, with its distinctive terraced crown, gleaming stainless steel gargoyles, and sunburst motifs, is arguably the most recognizable and beloved symbol of Art Deco architecture, a true monument to the machine age and modern aspiration.

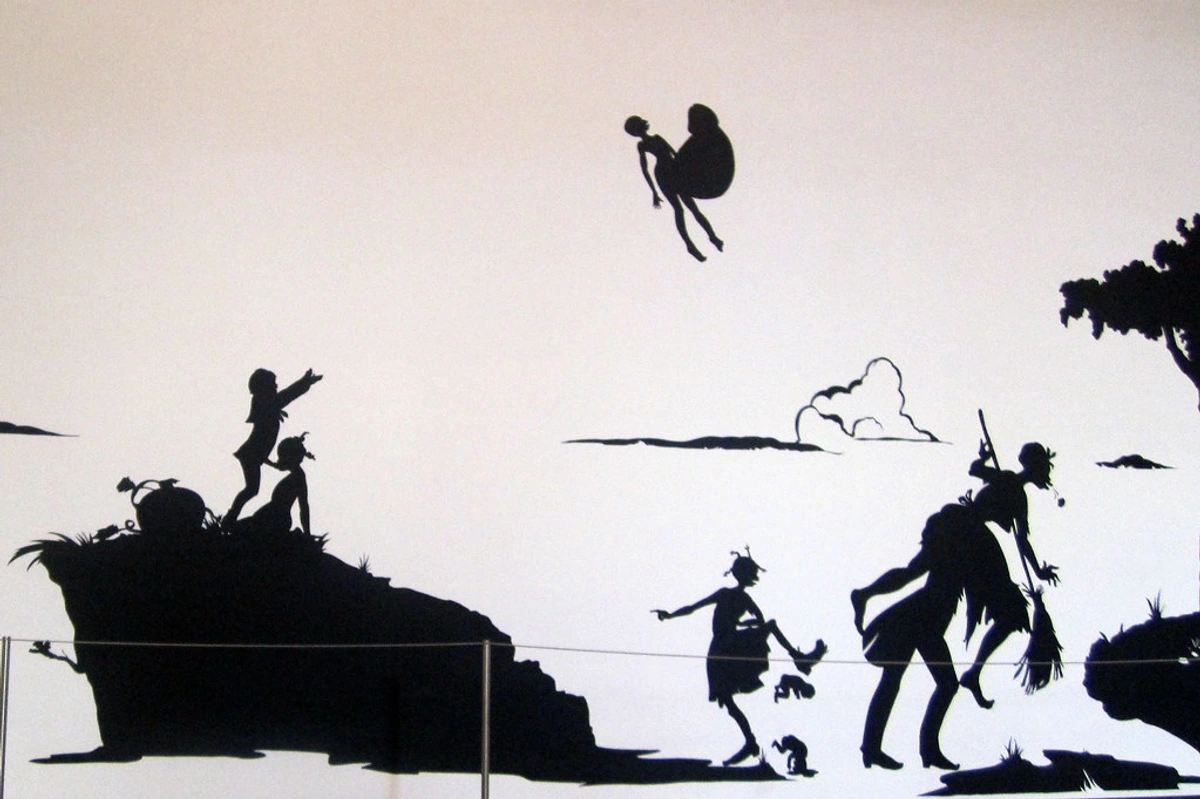

Aaron Douglas's 'Aspiration' from the Harlem Renaissance beautifully captures the forward-looking, geometric spirit of Art Deco, showing figures reaching towards a modern, hopeful future. This connection to the Harlem Renaissance illustrates how Art Deco's aesthetic became a powerful visual language for a new era of cultural and social awakening and empowerment. For a deeper dive, consider our ultimate guide to Art Deco movement.

The Core Differences: A Side-by-Side Look – Where the Rubber Meets the Road

The Core Differences: A Side-by-Side Look – Where the Rubber Meets the Road

Okay, this is it. This is where we get to the real meat of the matter. How do these two magnificent, utterly distinct styles truly stack up against each other? For me, as a curator, it’s in this direct, side-by-side comparison that their individual brilliance—and their profound differences—become most glaringly apparent. It's not just about what they are, but what they aren't in relation to each other, like defining light by understanding shadow.

Comparing the Titans: A Detailed Table

Feature | Art Nouveau (c. 1890-1910) | Art Deco (c. 1920-1930s) |

|---|---|---|

| Philosophy | Organic, anti-industrial, 'art for life,' handcrafted, spiritual, escapist, unity with nature | Modernity, industrial progress, luxury, machine aesthetic, functional, progressive, urban, streamlined |

| Key Inspiration | Nature, flowing water, female form, Symbolism, Pre-Raphaelites, Japanese prints, botany | Machine Age, geometry, ancient Egypt, Aztec, Cubism, Futurism, jazz, speed, aviation, monumental forms |

| Forms & Lines | Asymmetrical, curvilinear, 'whiplash' lines, organic, serpentine, delicate, dynamic | Symmetrical, rectilinear, angular, streamlined, geometric, bold, monumental, repetitive, zigzag, chevron |

| Motifs | Flowers (lilies, irises, orchids), vines, insects (dragonflies, butterflies), peacocks, mythical figures, sensuous female forms | Zigzags, chevrons, sunbursts, stepped forms, lightning bolts, fountains, aerodynamic shapes, stylized animals, gazelles, dancers |

| Materials | Iron, glass, ceramic, wood, precious metals (often with enamel, opals, horn), sometimes natural stone, stained glass | Chrome, stainless steel, glass, Bakelite, lacquer, exotic woods (ebony, zebrawood), sharkskin, ivory, mirrors, marble, aluminum |

| Overall Mood | Ethereal, romantic, whimsical, decorative, natural, sensual, often melancholic, contemplative | Glamorous, sophisticated, modern, luxurious, bold, optimistic, dynamic, sleek, celebratory, energetic |

| Geographical Spread | Strong in France, Belgium, Germany (Jugendstil), Austria (Secession), Spain (Modernisme), widespread but with regional variations | Global, especially prominent in France, USA, UK, and spread through international expositions, mass media |

| Typical Mediums | Architecture, furniture, jewelry, graphic arts, stained glass, textiles, ceramics | Architecture, interiors, fashion, jewelry, graphic design, industrial design, sculpture, painting |

Key Artists and Designers: The Hands That Shaped the Eras

Movement | Key Artists/Designers | Notable Works/Contributions |

|---|---|---|

| Art Nouveau | Alphonse Mucha, Gustav Klimt, Victor Horta, René Lalique, Antoni Gaudí, Charles Rennie Mackintosh | Posters (Mucha), Paintings ('The Kiss' - Klimt), Architecture (Horta Houses, Casa Batlló - Gaudí), Jewelry & Glass (Lalique), Furniture (Mackintosh) |

| Art Deco | Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann, Tamara de Lempicka, Erte, Raymond Hood, William Van Alen, Paul Poiret | Furniture (Ruhlmann), Paintings (Lempicka portraits), Fashion Illustration (Erte), Architecture (Chrysler Building - Van Alen, Rockefeller Center - Hood), Couture (Poiret) |

Color Palettes: A Spectrum of Expression

Beyond forms and lines, the very colors chosen tell a story of each movement's soul:

- Art Nouveau: Typically favored muted, earthy tones alongside richer, jewel-like hues. Think moss greens, olive, mustard yellows, soft lilacs, deep purples, and blues, often accented with gold or silver. The palette aimed to evoke the subtle, shifting shades of nature, sometimes with an almost mystical quality. Think iridescent qualities of dragonflies or the subtle blush of a water lily. I find this connection to the natural world in color profoundly inspiring for how I layer colors in my abstract works, seeking a similar depth and organic flow.

- Art Deco: Embraced bold, often high-contrast, and glamorous color schemes. Rich jewel tones like emerald green, sapphire blue, ruby red, and amethyst purple were common, frequently combined with metallics—gold, silver, chrome—and stark blacks, whites, and creams. The colors were chosen to project luxury, sophistication, and a dynamic modernity, often reminiscent of precious stones or exotic materials. This bold, unapologetic use of color and contrast is something that still resonates deeply in contemporary design, including my own pieces, where I often play with strong juxtapositions to create impact.

Societal Context and Cultural Impact: More Than Just Aesthetics

To truly understand these movements, we have to look at the world they inhabited and the impact they had beyond just beautiful objects:

- Art Nouveau: Emerged as a reaction to the perceived ugliness and dehumanization of the Industrial Revolution. It was a quest for beauty in everyday life, a romantic longing for a connection to nature, and a rejection of academic historicism. Its focus on craftsmanship was also a social statement, valuing the artisan over mass production. It resonated with the Aesthetic Movement and Symbolism, often carrying a sense of introspection and sometimes melancholy, reflecting the fin-de-siècle mood and a yearning for a return to simpler, more beautiful times.

- Art Deco: Was the aesthetic of a post-World War I world eager for optimism, progress, and pleasure. It celebrated the 'Roaring Twenties,' the Jazz Age, and the machine age, embodying newfound freedoms and technological marvels. It was the style of flappers, Hollywood glamour, and the rise of consumer culture. Its global spread was facilitated by international expositions and mass media, making it a truly popular and widely accessible style that symbolized modern living, speed, and luxury. It was less about social critique and more about celebrating a new era of prosperity and technological advancement, a mood that, I've noticed, often bubbles up after periods of great hardship, a collective desire for joy and progress.

Feature | Art Nouveau (c. 1890-1910) | Art Deco (c. 1920-1930s) |

|---|---|---|

| Philosophy | Organic, anti-industrial, 'art for life,' handcrafted, spiritual, escapist | Modernity, industrial progress, luxury, machine aesthetic, functional, progressive |

| Key Inspiration | Nature, flowing water, female form, Symbolism, Pre-Raphaelites, Japanese prints | Machine Age, geometry, ancient Egypt, Aztec, Cubism, Futurism, jazz, speed, aviation |

| Forms & Lines | Asymmetrical, curvilinear, 'whiplash' lines, organic, serpentine, delicate | Symmetrical, rectilinear, angular, streamlined, geometric, bold, monumental |

| Motifs | Flowers (lilies, irises, orchids), vines, insects (dragonflies, butterflies), peacocks, mythical figures | Zigzags, chevrons, sunbursts, stepped forms, lightning bolts, fountains, aerodynamic shapes, stylized animals |

| Materials | Iron, glass, ceramic, wood, precious metals (often with enamel, opals, horn), sometimes natural stone | Chrome, stainless steel, glass, Bakelite, lacquer, exotic woods (ebony, zebrawood), sharkskin, ivory, mirrors, marble |

| Overall Mood | Ethereal, romantic, whimsical, decorative, natural, sensual, often melancholic | Glamorous, sophisticated, modern, luxurious, bold, optimistic, dynamic, sleek |

| Geographical Spread | Strong in France, Belgium, Germany (Jugendstil), Austria (Secession), Spain (Modernisme) | Global, especially prominent in France, USA, UK, and spread through international expositions |

Form vs. Function, Nature vs. Machine: A Philosophical Divide

For me, the most striking—and perhaps most telling—difference lies in their fundamental philosophical approach to form itself. Art Nouveau's forms feel almost biological, growing and evolving with an organic vitality. They are a direct, passionate rejection of the rigidity and standardization of industrial production, almost a yearning for a pre-industrial Eden. It's an art that strives to dissolve the very boundaries between fine art and applied art, manifesting as one cohesive, fluid, natural expression. It’s about creating a unified aesthetic experience where everything flows harmoniously, much like nature itself. This focus on organic form in abstract art continues to inspire many contemporary artists, who find endless possibilities in its naturalistic curves and inherent dynamism.

Art Deco, conversely, doesn't just tolerate the machine; it celebrates it. Its forms are precise, often modular, incredibly functional, and directly derived from industrial design, modern transportation (think streamlined cars, trains, and ocean liners), and the efficiency of the factory. It speaks to speed, to progress, to the thrilling excitement of a new, technologically advanced era. The gentle, often melancholic asymmetry of Art Nouveau gives way to the bold, confident, and frequently repeated symmetry of Art Deco, reflecting a world eager to move forward with purpose and power.

Where They Overlap (Briefly): Shared Aspirations, Different Journeys

It's a common misconception that art movements click on and off like light switches. In reality, they flow, they merge, they overlap, often with fascinating transitional periods where echoes of the past mingle with whispers of the future. Both Art Nouveau and Art Deco, despite their stark differences, shared a profound, foundational desire: to decisively break away from the historical revival styles (the Neo-Gothic, the Neo-Classical, the Rococo imitations that had dominated the 19th century). They wanted to create something utterly, undeniably modern for their respective times—an art that spoke to the present, not the past. They both aimed for a 'total style,' influencing everything from grand architectural visions to the most intimate fashion accessories, seeking to imbue every aspect of life with a coherent aesthetic. And crucially, both were international movements, spreading their influence across continents, even if they manifested with delightful and distinct regional variations, such as Jugendstil in Germany or Modernisme in Spain. It's a reminder that even in opposition, there can be shared ground, a common root in the desire for something new, something that truly spoke to their present moment. The journey from one to the other, while marked by stark stylistic shifts, was driven by a shared, underlying impulse to innovate, something that continually fascinates me when I look at the evolution of modern art.

Why Does It Matter Today? Echoes in Contemporary Design and My Own Work

So, why dedicate so much time to these seemingly distant historical movements? For me, as an artist constantly grappling with the present, understanding Art Nouveau and Art Deco isn't just about a dusty appreciation of historical aesthetics. It's about seeing the living, breathing roots of contemporary design, art, and even our modern abstract movements. These pioneers laid profound foundations for how we conceptualize form, function, decoration, and even the emotional resonance of an object or space. From the organic flow in graphic design to the sleek lines of modern furniture, the bold patterns in textiles to the innovative use of materials, you can absolutely still trace their indelible influence. They were, in their own ways, both radical and forward-thinking, paving the way for what we now understand as modern art and even contemporary art, proving that art isn't just a reflection, but a driver of cultural evolution.

Looking at my own work—which, as you know, is often vibrantly contemporary and abstract—I find myself constantly reflecting on the bold statements and intricate details these movements pioneered. Art Nouveau’s embrace of natural forms and flowing lines, for instance, still informs how I think about organic shapes and movement in my pieces, how they interact and evolve on the canvas. Similarly, Art Deco’s crisp geometry and dynamic compositions echo in the structured elements and vibrant energy I try to capture, the way light plays on sharp edges and bold forms. It’s a powerful reminder that art is an ongoing conversation across time, a continuous dialogue between past and present, and that genuine inspiration can be found in the most unexpected historical places. If this discussion has sparked your own interest in the fascinating evolution of modern art, and how these historic currents flow into the contemporary art world I inhabit, perhaps a piece from my collection might resonate, or a visit to the Den Bosch Museum to see historical influences firsthand. I truly believe that to understand where we're going, we must first understand where we've been, and the Art Nouveau influence on modern design and the enduring influence of Art Deco on modern abstract design and architecture are perfect, luminous examples of this eternal artistic conversation.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Here, I'll address some of the most common questions I get asked, hoping to demystify these movements a little further. Because, let's be honest, distinguishing between these two can feel like a pop quiz, and I want you to ace it every time!

Q: What does Art Nouveau mean?

A: Art Nouveau is French for 'New Art.' The term itself emerged in the 1890s, notably from Siegfried Bing's Parisian gallery, Maison de l'Art Nouveau, which championed contemporary art and design that broke from historical styles. It truly aimed to be a fresh start, a complete aesthetic overhaul, rather than just another revival style. It's not just a name; it's a statement of intent. It was a conscious effort to create a modern style for a new century, rejecting the copying of past aesthetics and instead looking to nature and innovative forms for inspiration.

Q: What are the origins of the terms 'Art Nouveau' and 'Art Deco'?

A: The term Art Nouveau literally means 'New Art' in French, coined from the name of Siegfried Bing's Parisian gallery, 'Maison de l'Art Nouveau,' which opened in 1895 and showcased modern decorative arts, championing a radical break from historical pastiche. Art Deco, on the other hand, is a shortened form of 'Arts Décoratifs,' derived from the 1925 Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes held in Paris, which was a seminal event for the style. It's fascinating how a gallery and an exhibition became namesakes for entire artistic eras, isn't it? It highlights how these movements were deeply embedded in contemporary culture and commerce from their very inception, moving art out of traditional institutions and into the public sphere through commerce and grand public displays.

Q: Is Art Nouveau the same as Jugendstil?

A: That’s an excellent question, and one I hear often! While sharing core principles and the broader Art Nouveau aesthetic, Jugendstil is specifically the German term for Art Nouveau, particularly prevalent in Germany and the Nordic countries. It translates to 'Youth Style,' named after the influential art magazine Jugend. Regional variations are a hallmark of Art Nouveau; Jugendstil, for example, often had a slightly more abstract, rectilinear, and less curvilinear approach than its French or Belgian counterparts, sometimes reflecting a greater influence from traditional German craft movements. You'll also encounter terms like 'Stile Liberty' in Italy and 'Secessionstil' in Austria, the latter of which we explore in our guide to The Vienna Secession: Art Nouveau's Radical Austrian Cousins. It just goes to show how a central idea can blossom into wonderfully diverse local expressions, each responding to local cultural nuances, much like how my own abstract pieces are influenced by the specific light and mood of my studio.

Q: What came first, Art Nouveau or Art Deco?

A: To put it simply, Art Nouveau arrived on the scene first, emerging around 1890 and largely declining by 1910, effectively ending with the outbreak of World War I. Art Deco then followed, dominating from the vibrant 1920s into the 1930s, essentially spanning the interwar period. So, there's a distinct chronological gap, though, as I mentioned, artistic movements rarely have clean-cut beginnings and endings. There was a brief transitional period—roughly the 1910s—where the fading whispers of Art Nouveau met the bold, emerging pronouncements of Art Deco, but they largely represent different historical moments and profoundly different responses to their respective eras. This transition showcases how societal changes profoundly impact artistic sensibilities, a dynamic I constantly observe in the contemporary art world as well.

Q: How did World War I influence these movements?

Q: What about the term 'Modernisme' in relation to Art Nouveau?

A: Modernisme is the Catalan term for Art Nouveau, primarily flourishing in Catalonia, Spain, and epitomized by the visionary work of Antoni Gaudí in Barcelona. While it shares the organic forms, nature-inspired motifs, and emphasis on craftsmanship of Art Nouveau, Modernisme often incorporated unique local traditions, vibrant colors, and a distinctive sense of fantasy and monumental scale. It was a regional expression that embraced its unique cultural identity while contributing to the broader 'New Art' movement, proving that innovation can thrive through local lenses.

Q: What role did women play in Art Nouveau and Art Deco?

A: Women played significant and often groundbreaking roles in both movements, though in different ways. In Art Nouveau, women were frequently depicted as ethereal muses, goddesses, and sensuous figures, central to its nature-inspired iconography, especially in posters by Mucha and jewelry by Lalique. Beyond being subjects, women artists and designers like Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh (Charles Rennie Mackintosh's wife and collaborator) were instrumental in developing the Glasgow Style. For Art Deco, women were not only central to the glamorous 'flapper' image and fashion, but also as influential designers. Artists like Tamara de Lempicka (whose bold portraits defined the era) and designers like Eileen Gray challenged traditional roles, creating furniture and interiors that embodied modern living and female independence. Both periods offered new opportunities for women to engage with art and design, both as creators and as powerful cultural symbols.

Q: How did Cubism influence Art Deco?

A: While Cubism and Art Deco are distinct movements, Cubism's revolutionary breakdown of forms into geometric planes certainly provided a fundamental influence on Art Deco's aesthetic. Cubist artists like Picasso and Braque shattered conventional perspective, presenting objects from multiple viewpoints simultaneously, and often reducing them to their underlying geometric structures. This emphasis on geometric abstraction, symmetry, and angularity was eagerly adopted by Art Deco designers. They reinterpreted these principles not for Cubism's analytical exploration of reality, but for decorative purposes, creating the iconic zigzags, stepped forms, and streamlined patterns that characterize Art Deco architecture, furniture, and graphic design. It was less about fragmenting reality and more about assembling it into a sleek, modern, and luxurious aesthetic.

Q: What is the relationship between Art Deco and the Jazz Age?

A: The Jazz Age is almost synonymous with the Art Deco era, particularly in the United States and parts of Europe. It was a period of cultural explosion, marked by the rise of jazz music, new social freedoms, economic prosperity (especially in the 'Roaring Twenties'), and a general atmosphere of hedonism and optimism following World War I. Art Deco became the visual soundtrack to this era. Its opulent materials, sleek lines, and celebratory motifs perfectly mirrored the glamour, excitement, and modernity of jazz clubs, flapper fashion, grand ocean liners, and soaring skyscrapers. Art Deco design embodied the energy, rhythm, and sophistication of the Jazz Age, providing a stylish backdrop to a period of unprecedented social and cultural change, a truly symbiotic relationship that defined an entire generation. For me, the music and the art of that era are inextricably linked, each feeding into the other's vibrant energy.

Q: Are there any transitional styles between Art Nouveau and Art Deco?

A: Yes, absolutely! Art movements rarely have sharp cut-off points; they often evolve and transition, sometimes in fascinating ways. The period roughly spanning the 1910s is often seen as a transitional phase, where the organic excesses of Art Nouveau began to recede, and the bolder, more geometric inclinations of what would become Art Deco started to emerge. Styles like the Viennese Werkstätte (co-founded by Josef Hoffmann and Koloman Moser, who were part of the Vienna Secession) retained the artisanal quality of Art Nouveau but moved towards a more rectilinear and austere aesthetic, foreshadowing Art Deco's geometric rigor. Similarly, some early modernist architectural experiments in Germany and the Netherlands also showed a move away from ornamentation towards cleaner lines. These transitional styles illustrate a broader shift in aesthetic taste and cultural values, paving the way for the full flourishing of Art Deco in the 1920s.

credit, licence A: World War I played a significant, almost definitive, role in the decline of Art Nouveau and the subsequent rise of Art Deco. Art Nouveau's emphasis on elaborate, expensive craftsmanship, often involving painstaking handwork, felt utterly out of place in the grim realities and economic hardships of wartime. Its romantic, often melancholic and introspective aesthetic, focused on a fantastical escape to nature, didn't align with the stark, pragmatic, and forward-looking post-war desire for optimism, efficiency, and progress. Art Deco, emerging after the war, was a direct response to this cultural shift, embracing modernity, industry, and a more streamlined, celebratory spirit that mirrored the era's hope for a new, brighter, and faster future. The war wiped the slate clean, making way for a completely new vision, a stark reminder that even in devastation, humanity finds a way to envision and create anew.

Q: Can a building be both Art Nouveau and Art Deco?

A: Not typically, as their aesthetic principles are fundamentally quite distinct, almost opposing. Art Nouveau's organic curves and asymmetry clash quite dramatically with Art Deco's precise geometry and symmetry. Imagine trying to fuse a wild vine with a perfectly cut gear – it's a difficult visual juxtaposition! However, during the brief, fascinating transitional period—roughly the 1910s to early 1920s—some architects or designers might have shown influences from both, experimenting as styles evolved and a new aesthetic vocabulary was being forged. Think of some early modernist designs that began to strip away Art Nouveau's ornamentation but hadn't yet fully embraced Art Deco's sharp angles. But generally, a building will strongly align with one style or the other, showcasing a clear preference for either nature's flow or the machine's precision. It's rare to see a true, harmonious hybrid; they're usually distinct statements. This reminds me of how artists today often draw from various movements, but a cohesive vision still often leans more heavily on one primary aesthetic.

Q: What are some famous examples of Art Nouveau architecture?

A: Oh, there are so many exquisite examples, each one a testament to the movement's desire to integrate art into life! Iconic architectural marvels include Antoni Gaudí's fantastical Casa Batlló and the still-under-construction Sagrada Familia in Barcelona—each a swirling, organic dreamscape that feels more grown than built. In Brussels, Victor Horta's Horta House (and other private residences like Hôtel Tassel and Hôtel van Eetvelde) are stunning examples of his innovative 'whiplash' lines and integrated design, where every detail from floor to ceiling is part of the whole. The ornate, cast-iron Paris Métro entrances by Hector Guimard are ubiquitous symbols of the style, transforming mundane public infrastructure into elegant gateways. And, of course, the elegant Vienna Secession Building in Austria, a temple to 'New Art,' is another prime example, asserting its aesthetic with bold gold leaf and stark, yet decorative, lines. Each of these truly captures the movement's ambition to create a unified, immersive artistic experience, extending from the grand exterior to the smallest interior detail.

Q: What are some famous examples of Art Deco architecture?

A: For Art Deco, we're talking about structures that scream 'modern,' 'glamour,' and 'progress.' The list is long and impressive! Foremost are New York City's iconic Chrysler Building, with its terraced, sunburst crown, and the towering Empire State Building—symbols of American ingenuity, luxury, and upward mobility. The Marine Building in Vancouver is another fantastic example, with its intricate nautical motifs, as is the impressive Guardian Building in Detroit, a 'Cathedral of Finance' known for its vibrant tilework. And you can't talk about Art Deco architecture without mentioning the sprawling, perfectly preserved Art Deco Historic District in Miami Beach, a vibrant collection of hotels and beachfront properties that capture the playful, luxurious side of the style. Beyond these, its distinctive influence is seen in countless cinemas, public buildings, and even train stations (like Union Terminal in Cincinnati) and residential complexes across the globe, all designed to evoke speed, sophistication, and the thrilling pulse of progress. These buildings are more than just structures; they are monuments to an era's aspirations.

Q: Which came first: Cubism or Art Deco?

A: Cubism, pioneered by Picasso and Braque, emerged around 1907, significantly before Art Deco, which gained prominence in the 1920s. So chronologically, Cubism was a precursor, laying some of the theoretical groundwork for geometric abstraction. While chronologically distinct, Cubism's revolutionary breakdown of forms into geometric planes certainly influenced Art Deco's embrace of geometric shapes and abstract patterns. Art Deco, however, applied these geometric principles with a focus on decoration, luxury, and streamlined modernity, rather than Cubism's analytical exploration of multiple perspectives and fractured realities. Cubism broke forms apart; Art Deco reassembled them into sleek, elegant compositions, often for purely aesthetic and decorative purposes. It's a fantastic example of how artistic theories can be reinterpreted and applied in entirely new contexts, a process I see echoed in how contemporary abstract artists re-engage with historical forms.

Conclusion: A Timeless Dialogue of Design

So there you have it. Art Nouveau and Art Deco, though often casually grouped, are, in my view, two fundamentally different, yet equally powerful, artistic expressions of their respective eras. One, a romantic, flowing ode to nature, craftsmanship, and a spiritual connection to the organic world; the other, a bold, geometric embrace of modernity, luxury, and the thrilling promise of the machine age. As we've curated this side-by-side comparison, I truly hope you’ve gained a deeper appreciation for their individual spirits, their unique narratives, and the sheer genius behind each. Each movement, in its own inimitable way, sought to define the future, leaving an indelible, vibrant mark on the grand canvas of art history. Their influences, whether subtle or overt, continue to shape artists and designers right up to today. To place them in the broader sweep of art, take a moment to explore our comprehensive timeline, and perhaps you’ll see even more clearly how these historic currents flow directly into the contemporary art world I inhabit. The conversation, after all, in art and life, never truly ends; it just evolves and finds new forms, new expressions, always building on what came before.

If this discussion has truly sparked your interest in the intricate evolution of art and design – and I sincerely hope it has – I wholeheartedly encourage you to delve even deeper into these magnificent movements. Discover how their groundbreaking principles still subtly, or dramatically, shape our contemporary visual world. There’s a lifetime of beauty and insight waiting to be uncovered, and I invite you to keep exploring, questioning, and most importantly, seeing—because that's where true appreciation and understanding begin. And if you’re ever curious to see how these historical threads weave into my own contemporary abstract pieces, a visit to my collection or the Den Bosch Museum might just be the next step in your artistic journey. After all, understanding the past is the surest way to truly appreciate the innovations and expressions of the present. I believe it's an endless conversation, one I'm thrilled to be a part of, and one I hope you'll continue to engage with.