Unlearning Art History: Indigenous Roots of Abstract Art & My Journey

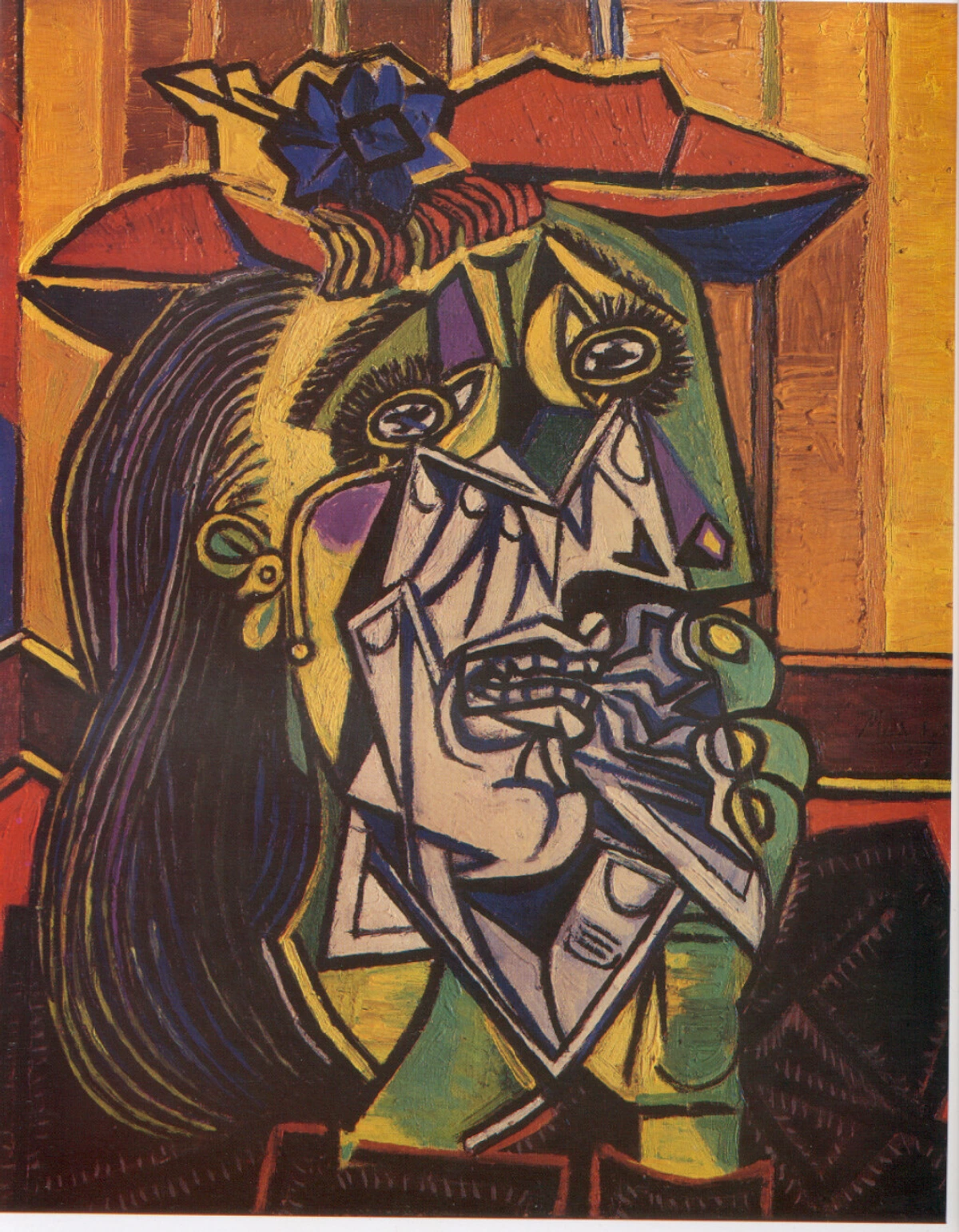

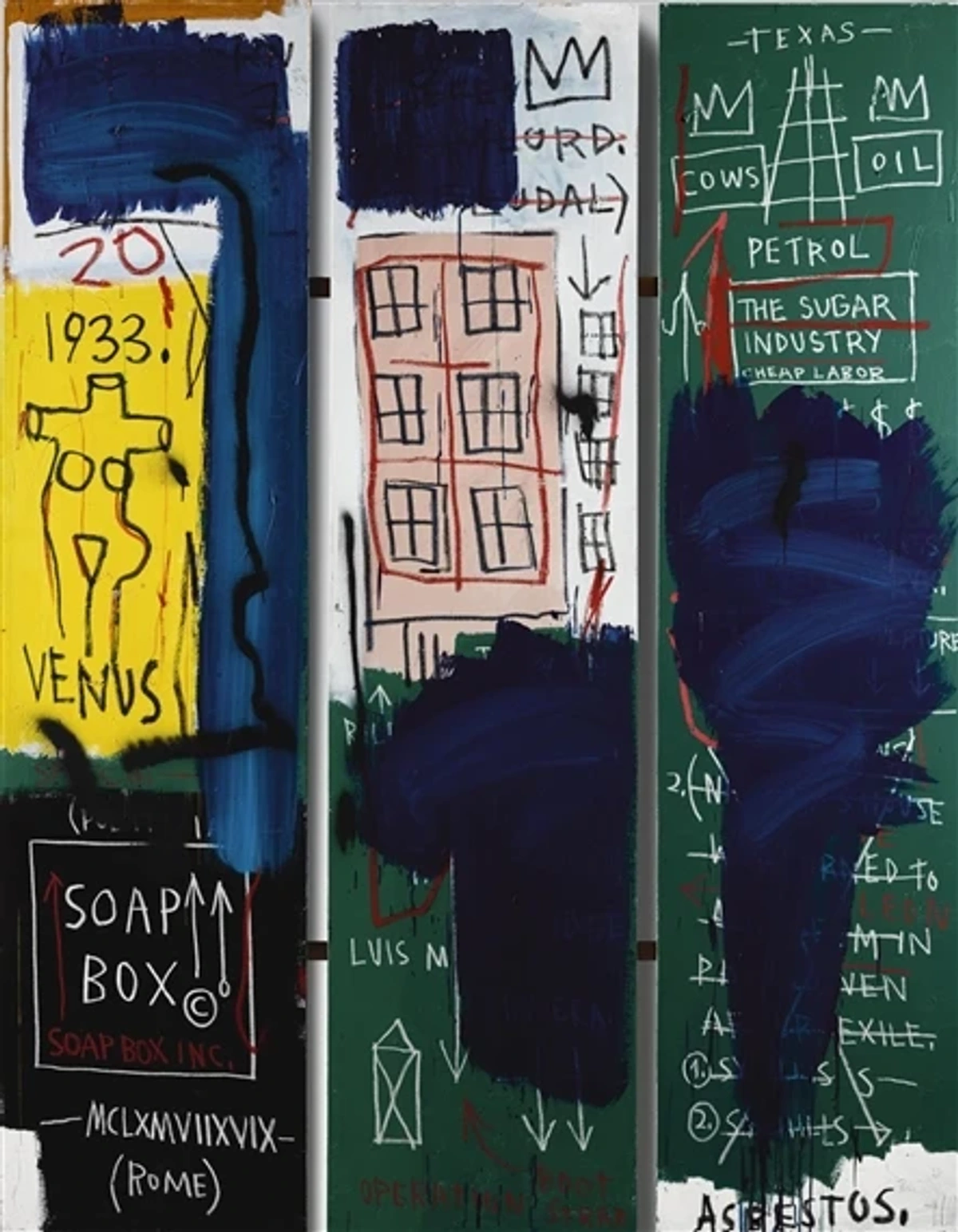

Uncover the profound, complex influence of global indigenous art on modern abstraction and my personal journey of unlearning Eurocentric art history. Explore the raw power that shaped Picasso, Matisse, Basquiat, and my own evolving artistic vision, and learn how to engage ethically.