Japanese Aesthetics in Abstract Art: Wabi-Sabi, Ma & My Creative Journey

Explore how Wabi-Sabi, Ma, and other core Japanese aesthetics profoundly influenced Western abstract art, from early Japonisme to Minimalism. Discover key artists, movements, and my personal journey integrating these philosophies into contemporary art.

The Silent Echo: How Japanese Aesthetics Reshaped Western Abstract Art (and My Own Work)

Ever felt that profound sense of 'just rightness' in art? Not perfection, because perfection often feels sterile, but a quiet, resonant truth where every element, even the empty space, hums with purpose? For me, this elusive quality always whispered in the abstract compositions that captivated my soul. It was only when I unearthed the profound philosophies of Wabi-Sabi and Ma – cornerstones of Japanese aesthetics – that I found the secret language to decode this feeling, not just in the works of Western abstract masters, but in my own art. Suddenly, that ineffable 'rightness' had a name, a lineage, a deeply felt philosophy.

It’s like finally learning the name for that weird ache in your knee after a long hike; suddenly, it makes sense. And once you truly see these influences, they become an undeniable, beautiful connection across vast distances. This isn't merely a historical footnote; it’s a living, breathing testament to how art transcends borders and time, subtly shaping the very fabric of how we create and perceive. So, come with me, and let's unravel this beautiful, quiet dialogue between East and West. Perhaps, you'll find your own 'secret language' too.

Japonisme: The First Brushstrokes of Influence

Before we dive into the profound philosophical echoes, it's important to understand the initial, more tangible encounter between East and West. The opening of Japan in the mid-19th century sparked a widespread phenomenon known as Japonisme in Europe. Western artists, designers, and collectors became utterly fascinated by Japanese woodblock prints (ukiyo-e), ceramics, lacquerware, fans, and textiles. This wasn't just a fleeting trend; it led to a pervasive influence on movements like Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, and Art Nouveau.

Artists like Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, and Vincent Van Gogh were captivated by the flattened perspectives, bold outlines, and asymmetric compositions of ukiyo-e. They eagerly integrated these revolutionary elements into their landscapes, portraits, and genre scenes. Monet’s series of Japanese bridge paintings at Giverny are an obvious homage, while Degas's innovative use of cropped views and high-angle perspectives directly mirrors compositional strategies seen in ukiyo-e. Van Gogh's vibrant colors and strong brushstrokes also showed a clear debt to Japanese printmaking, often depicting specific Japanese motifs. This early, more direct adoption of Japanese visual strategies laid crucial groundwork, slowly acclimatizing the Western artistic eye to alternative ways of seeing and composing, paving the way for the later, more subtle philosophical influences on abstraction. It was like a new visual vocabulary being introduced, setting the stage for deeper, more introspective conversations that would echo through abstract art for generations.

![]()

Whispers from the East: Unpacking the Core Concepts

While Japonisme introduced visual novelties, the deeper currents of Japanese aesthetics offered profound ways of seeing and creating. These aren't just art terms; they're philosophies, ways of seeing the world that, for me, have become lenses through which I decode abstract art and life itself.

Wabi-Sabi: The Beauty of Imperfection

Oh, Wabi-Sabi. It's the philosophy that finally gave me permission to breathe. It’s the appreciation of the transient, the imperfect, the understated. Think of a cracked teacup, lovingly repaired through the practice of kintsugi (golden joinery), telling a story of its journey rather than hiding its past. Or a weathered stone, smoothed by time and elements, bearing the marks of time with dignity. It's about finding beauty in austerity, in the marks of time, in natural asymmetry. For someone like me, who battles a constant inner critic demanding perfection, Wabi-Sabi is a gentle whisper: "It’s okay. It's more than okay. It's beautiful exactly as it is."

How does this translate to abstract art? Imagine the raw, unpolished honesty of a canvas, the visible brushstrokes, the accidental drips, the slightly uneven edges. It's the antithesis of sterile, mass-produced perfection. Think of the raw, almost scarred surfaces in Anselm Kiefer's works, where materials tell a story of decay and transformation, or the visceral textures of a Gerhard Richter abstract painting. It's the soul of intuitive painting, where the artist embraces spontaneity and the inherent beauty of material imperfections rather than fighting them. It’s about accepting the unexpected beauty of imperfection.

Ma: The Profound Power of Empty Space

Then there’s Ma. If Wabi-Sabi finds beauty in the object's inherent nature, Ma is about the space between objects – a concept Western art often refers to as negative space. It's the intentional pause, the interval, the void that allows everything else to breathe and gain significance. Think of the silence between notes in a piece of music, or the empty space in a traditional Japanese garden that invites contemplation. It’s not just empty space; it’s active space, brimming with potential and suggestion. It’s the breath between words, the quiet before a revelation. In abstract art, Ma manifests as the deliberate use of negative space to define positive forms, to create tension, or to invite a sense of profound calm.

It's the understanding that what is not there can be just as powerful, if not more so, than what is present. For me, embracing Ma has been about learning to trust the pauses, the expanses of canvas that might seem "unfinished" to some. It’s about letting the painting breathe, rather than suffocating it with detail. Consider a minimalist sculpture by an artist like Richard Serra, where massive steel forms carve out powerful negative spaces that are as much a part of the artwork as the steel itself. It teaches me that true impact isn't always about shouting; sometimes, it’s about a whispered suggestion that resonates deeply, allowing the viewer's eye and mind to wander, to complete the narrative, to find their own meaning. This concept feels like the unseen structure, the invisible scaffolding that guides my abstract art and underscores the role of negative space in abstract art. How do you experience the quiet power of Ma in your own life?

Echoes in Western Abstraction: A Quiet Revolution

While early Western artists were charmed by Japanese motifs and compositions, a deeper, more philosophical engagement was quietly taking root. The impact of Japanese aesthetics on Western art is a long and rich story, and its silent echo in abstract art, where lines and forms speak without direct representation, is where it truly captivates me. It's like finding a familiar melody woven into a completely new symphony, subtly transformed but undeniably present.

The Raw Beauty of Abstract Expressionism (Wabi-Sabi's Kin)

Think of the raw energy of Abstract Expressionism. Artists like Jackson Pollock with his drip paintings, or Willem de Kooning's gestural canvases, embraced the accidental, the spontaneous, the immediate mark of the artist's hand. This wasn't about polished perfection; it was about process, emotion, and the undeniable presence of the artist's struggle and triumphs on the canvas. Pollock's "all-over" compositions, for instance, defy traditional focal points, creating a democratic surface where every mark, every splatter, contributes to the whole, embodying Wabi-Sabi's reverence for the unrefined and the 'as-is.' The visible texture, the energetic imperfections, the defiance of rigid form – these elements suggest an intuitive understanding of beauty found outside of conventional ideals. It’s about accepting the unexpected beauty of imperfection, even celebrating it. The primal authenticity of the mark, the evidence of human touch and struggle, connects deeply with the acceptance of natural processes and impermanence that Wabi-Sabi champions.

The Meditative Power of Minimalism (Ma's Manifestation)

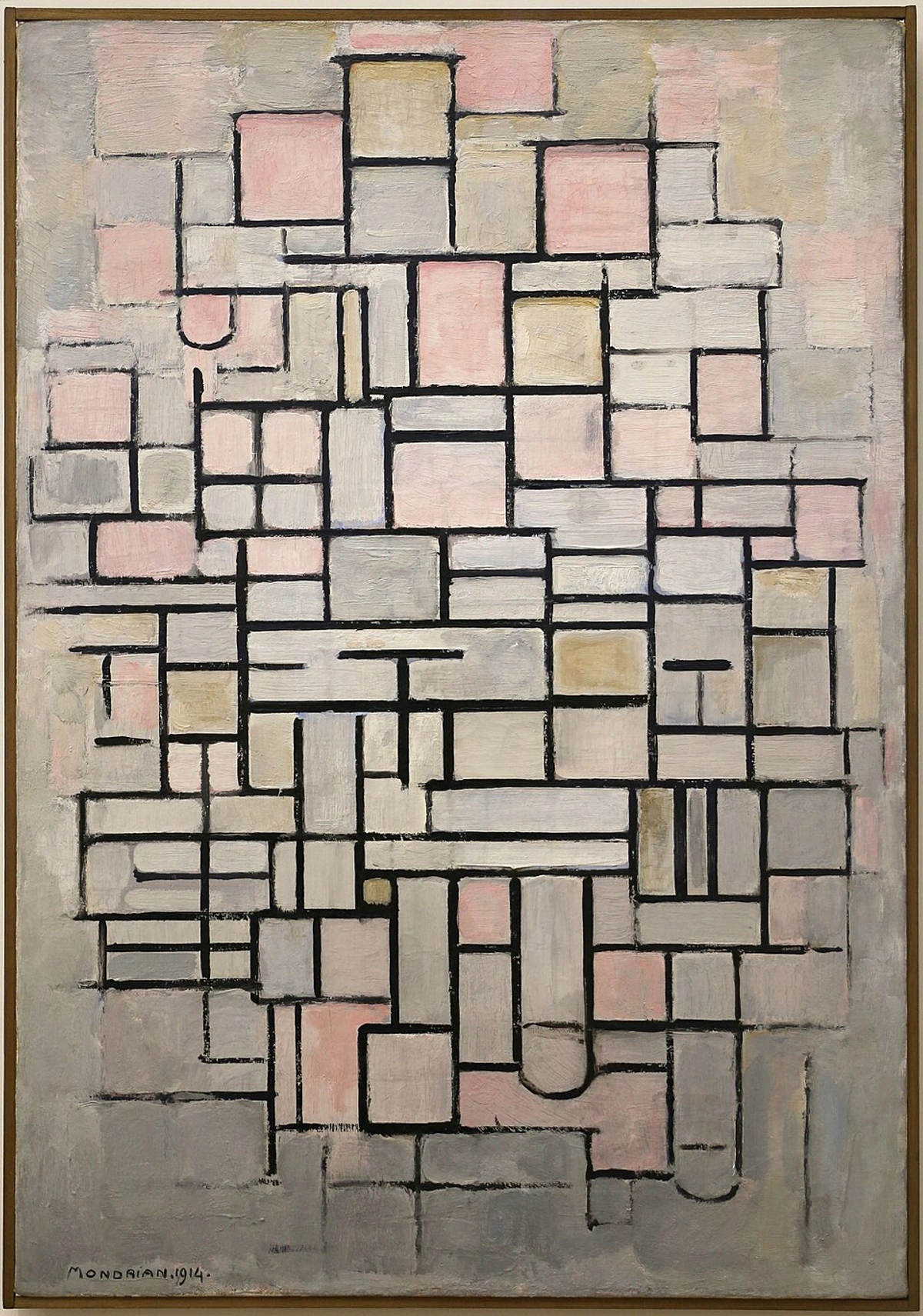

Then consider Minimalism, a movement that stripped art down to its essential elements, often focusing on simple geometric forms and vast, unadorned surfaces. Here, Ma finds a profound Western manifestation. Artists like Piet Mondrian, with his precise grids and limited color palette, used negative space as a crucial compositional element. Mark Rothko's large, hovering color fields invite contemplation, with the 'empty' space around and between the rectangles being as vital as the colors themselves, drawing the viewer into a meditative state. Agnes Martin's subtle, gridded canvases often feel like quiet meditations on infinity and emptiness, where the pauses and subtle variations become the subject. This deliberate reduction, an emphasis on what remains when all excess is removed, isn't just about 'less is more'; it's about the profound power held within the quiet, the sparse, the carefully considered absence. It invites the viewer to fill the void with their own contemplation, much like the empty space in a Zen garden. This quest for essentialism is at the heart of much of minimalist art and the power of negative space.

Beyond Wabi-Sabi and Ma: Deeper Philosophical Resonances

While Wabi-Sabi and Ma are the most tangible echoes, other Japanese aesthetic concepts also resonate with abstract art, subtly shaping how we perceive beauty and meaning. It's like listening for faint, almost imperceptible harmonies in a complex piece of music, revealing layers of understanding.

Iki: Understated Chic and Subtle Strength

Iki describes a beauty that is understated, chic, and subtle, often with a hint of sophistication or quiet strength. It's a beauty that grows on you, avoiding overt ornamentation or flashiness, commanding respect through its refined simplicity. While initially referring to urban style, its essence—a quiet confidence in presence—finds an echo in minimalist abstract art that achieves profound impact through restraint. Think of a perfectly balanced abstract composition where every element feels inevitable, without being loud or decorative – perhaps the quiet, understated strength found in certain minimalist art compositions that command attention through precise forms and subtle presence rather than overt drama.

Yūgen: Profound Mystery and Suggestion

Yūgen refers to a profound, mysterious sense of beauty, often evoked by things that are only partially seen or hinted at. It's the beauty of suggestion rather than full disclosure, of the unseen rather than the explicit. In abstract art, this translates to compositions that don't reveal all their secrets at once – perhaps a Mark Rothko color field with blurred edges hinting at vast, unknowable depths, or the layered translucency of Helen Frankenthaler's poured canvases, where forms emerge and recede like mist. It’s the feeling you get when you glimpse something beautiful just at the edge of your perception, leaving you with a lingering sense of wonder and curiosity, inviting you to lean in closer.

Shibui: Serene Elegance and Quiet Depth

Shibui describes a beauty that is understated, simple, and subtle, often with a hint of natural roughness or a quiet strength. It's a beauty that grows on you, avoiding overt ornamentation or flashiness. Think of muted color palettes, natural textures, and a harmonious balance that doesn't scream for attention but quietly commands respect. Many abstract artists, particularly those working with monochromatic schemes or earthy tones – perhaps the quiet strength of minimalist compositions or the subtle gridded works of artists like Agnes Martin – unknowingly tap into Shibui, creating works that are not immediately dramatic but offer a lasting, serene elegance. It's a beauty that whispers, rather than shouts, reflecting a quiet confidence in its own presence.

Mono no Aware: The Pathos of Impermanence

Mono no aware is the gentle sadness or poignant appreciation for the ephemeral nature of things, the beauty found in transience. It’s the bittersweet understanding that all things are impermanent, and this impermanence makes them all the more precious. In abstract art, this can be seen in the delicate, fading washes of color in a watercolor abstraction, the implied movement in a gestural painting that suggests a fleeting moment, or the sense of something dissolving or forming on a canvas. Even in my own vibrant abstract works, this pathos can be present in the way a color field subtly shifts, or a gestural mark dissolves, embracing the beautiful, transient nature of the artistic moment – a whisper of what once was or what is about to fade, making the present moment of viewing all the more poignant. This concept underpins much of what draws me to the raw, emotional language of color and the transient gestures in my own work.

Further Resonances in Abstract Practice: Kanso, Seijaku, Shizen

Beyond these, other principles subtly align with abstract thought and practice. Kanso (Simplicity), the elimination of clutter and finding beauty in extreme economy, echoes in minimalist drawings and paintings reduced to essential lines and forms, much like a Zen ink wash. Seijaku (Tranquility/Stillness), a quiet, contemplative calm, finds resonance in abstract works that evoke profound peace through vast, unbroken color fields or subtle textural variations. And Shizen (Naturalness/Absence of Artificiality), an effortless and unforced quality, aligns with organic abstraction, the use of natural pigments, or compositions that feel as though they simply are, rather than being meticulously constructed. These concepts encourage a stripping away of the superfluous, fostering a deeper connection to the essence of the art and the viewer's experience.

It’s crucial to acknowledge that while Western artists were inspired, their interpretation and adaptation of these concepts often occurred through their own cultural lenses. This wasn't always a direct translation but rather a fascinating transformation, sometimes leading to new insights, sometimes to a partial understanding or even a recontextualization that diverged from the original Japanese intent. This cross-cultural dialogue is rarely a one-to-one imitation, but rather a rich, ongoing conversation, evolving as each culture reflects on the other.

My Canvas, My Conversation: Weaving Eastern Thought into My Art

These aren't just academic concepts; they've become integral threads in the tapestry of how I approach my own abstract art. When I stand before a blank canvas, it's not just a void to be filled, but a space already potent with possibility – a canvas waiting for its own Ma. I remember one particular painting where I struggled for days, trying to 'fix' a seemingly accidental drip of paint, feeling that familiar internal critic screaming for perfection. It was only when I stepped back, and genuinely embraced the Wabi-Sabi philosophy, that I saw not a mistake, but a unique, beautiful mark of the process, a testament to the journey. I decided to highlight it, subtly, making it an intentional part of the piece. Similarly, I've learned to cultivate Ma, not just in my art, but in my studio; sometimes, the most profound decision is simply to stop, to leave a section of canvas unpainted, allowing the work to breathe and the viewer to complete the narrative. This mindful approach to creating, this trust in the unfinished, is a constant practice. For example, in a recent series, I deliberately left sections of raw canvas visible, allowing the texture and natural imperfections to become part of the finished piece, a nod to Wabi-Sabi’s acceptance of natural wear and tear. Similarly, the careful placement of vibrant color blocks in another series creates significant 'breathing room,' inviting the eye to rest and explore the negative space, directly informed by Ma.

Even in my contemporary, often vibrant and colorful abstract art, these philosophies are the unseen scaffolding – allowing a raw, visible brushstroke to remain, even if initially 'imperfect' (Wabi-Sabi), or strategically leaving vast expanses of canvas to breathe, inviting the viewer's gaze to wander and find meaning within the quietude (Ma). My journey as an artist has been a constant unraveling and re-weaving of influences, much like the layers of my paintings. From the initial spark of an idea to the final brushstroke, I’m listening to the canvas, allowing it to speak, and finding that often, it's speaking a language deeply attuned to these quiet Eastern philosophies. It's about finding freedom in imperfection, power in negative space, and a profound beauty in the subtle and the transient. What's fascinating is how these concepts, born in a different cultural context, can be interpreted and expressed through bold colors and dynamic forms, proving their universality.

It’s a dance between intention and intuition, a process where I’m not just making art, but exploring what it means to be alive, to observe, and to create something that resonates with that quiet "just rightness" I first spoke of. If you're curious to see how these philosophies manifest in my contemporary, colorful abstract art, I invite you to explore my available works or delve deeper into my artistic journey at my museum in 's-Hertogenbosch.

The Enduring Dialogue: Bridging East and West

The silent echo of Japanese aesthetics in Western abstract art is a testament to art's universal language. From the initial fascination of Japonisme to the profound philosophical undercurrents of Wabi-Sabi, Ma, Yūgen, Shibui, Mono no Aware, and others, these concepts have consistently invited Western artists to look beyond the obvious, embrace the essential, and find beauty in the understated. For me, discovering these concepts wasn't just an intellectual exercise; it was a profound personal revelation that transformed how I create and how I perceive the world around me. It's a dialogue that continues to inspire, inviting us all to look a little closer, listen a little more carefully, and find the profound in the quietly understated. Perhaps, in doing so, we might just discover a new secret language for our own souls, and perhaps even a new way to appreciate the power of negative space in abstract art or the unexpected beauty of imperfection that surrounds us. What quiet wisdom will you uncover in the spaces and imperfections of your world today?