Artists Inspired by Nature: Why the Wild Still Captures Our Creative Soul

Nature is an eternal muse for artists. Explore its influence through art history, from ancient times to contemporary environmental art, discover specific elements, techniques, and how to bring nature-inspired art into your space for well-being.

Artists Inspired by Nature: Why the Wild Still Captures Our Creative Soul

Nature. Just saying the word feels like a breath of fresh air, doesn't it? For me, as an artist, it's more than just a pretty backdrop; it's a constant, swirling source of ideas, feelings, and sometimes, utter frustration (ever tried painting outdoors when the wind decides your canvas is a kite, or a sudden downpour turns your carefully mixed pigments into muddy puddles?). I remember one particularly blustery day, setting up my easel by the coast, only for a rogue gust to send my canvas tumbling into the sand. A frustrating moment, sure, but the raw power of that wind, the way it whipped the sea into a frenzy – that energy found its way into my brushstrokes later. Or the time I was sketching a quiet forest stream, completely absorbed, only to look up and find a curious deer watching me from just a few feet away. It startled me, but that moment of unexpected connection, the feeling of being truly seen by the wild, was incredibly powerful and ended up influencing a series of abstract pieces about presence and observation. In a world that often feels increasingly complex and disconnected, I find the call of the wild, the grounding presence of nature, feels more vital than ever for creators and viewers alike. This article will explore this enduring relationship, from its ancient roots to its contemporary expressions, and how it continues to shape the creative soul.

Why is that? Why do we, as creators and as viewers, keep returning to trees, mountains, oceans, and skies? I think it's because nature speaks a language we instinctively understand, even if we can't always articulate it. It's about beauty, yes, but also about scale, cycles, raw power, and a profound sense of connection to something larger than ourselves. It's the ultimate muse – always changing, always challenging, and always, always there. It teaches us about imperfection and change, which, let's be honest, is a lot like life (and art!). The way a river carves through rock over millennia, or how a single flower unfolds its petals and then wilts – these are powerful lessons in process, resilience, and the transient beauty of existence. It's a constant reminder that nothing is static, and art, too, is a process of evolution. These fundamental aspects of the natural world provide artists with a kind of visual and energetic language to draw upon. Artists translate these concepts in countless ways: the immense scale of a mountain range might be captured in a vast canvas or a tiny, detailed drawing; the relentless cycles of growth and decay can be seen in studies of wilting flowers or abstract works about transformation; the imperfection of a gnarled tree branch can inspire a focus on texture and form over idealized beauty. It's this deep, multifaceted language that keeps artists coming back.

Nature Through Art History: A Timeless Muse

The idea that nature inspires artists isn't new; it's woven into the very fabric of human creativity, stretching back far beyond the periods we typically study in art history books. Think of the earliest known artworks – the incredible cave paintings at places like Lascaux or Altamira. These weren't just random scribbles; they were powerful depictions of animals, capturing their energy and form, a clear testament to the deep connection early humans felt with the natural world around them. Or consider ancient Egyptian art, where the Nile River, the sun, and various animals were central to their symbolism and depicted in hieroglyphs, tomb paintings, and sculptures. Medieval illuminated manuscripts often featured intricate borders filled with detailed drawings of plants, flowers, and insects, showing a fascination with the small wonders of the natural world, even within religious texts.

Looking back through the history of art, you see nature woven into the fabric of almost every movement. It's not just about painting pretty pictures of landscapes; it's about capturing the feeling of being in nature, the light, the atmosphere, the sheer force of it all. Artists didn't just depict nature; they used it to explore new techniques and express evolving philosophies. It's fascinating to see how artists across centuries have grappled with the same fundamental inspiration, each finding their own unique way to translate the wild onto canvas or into form. It certainly makes me feel part of a long, messy, beautiful lineage.

Ancient Roots and Early Observations

As mentioned, the connection goes back to cave paintings, but early civilizations like the Egyptians and Mesopotamians also incorporated natural elements extensively in their art, often for symbolic or religious purposes. The Greeks and Romans depicted nature in mosaics, frescoes, and sculptures, often in idealized forms or as settings for mythological scenes. This laid some groundwork for later Western traditions.

Renaissance and Scientific Observation

Even in the Renaissance, nature wasn't just a setting but a subject. Artists like Leonardo da Vinci meticulously studied botany and geology, incorporating detailed natural elements into their works. This scientific observation influenced their realistic rendering techniques. His detailed drawings of plants, like the Star-of-Bethlehem and Other Plants, show an almost scientific precision that informed the lush, believable flora in paintings like the Annunciation or Virgin of the Rocks. Albrecht Dürer's famous Great Piece of Turf isn't a grand vista, but a humble, almost scientific study of a patch of weeds – a testament to the beauty found in the smallest details, rendered with incredible precision. It's a reminder that even the most mundane patch of grass can be a universe of complexity if you just look closely enough. In the Dutch Golden Age, artists like Jacob van Ruisdael and Meindert Hobbema captured the everyday beauty of their surroundings, from detailed botanical studies to vast skies over flat lands, establishing landscape painting as a respected genre. Still life painting also flourished, with artists like Rachel Ruysch creating incredibly detailed and symbolic arrangements of flowers, insects, and fruits, celebrating the beauty and transience of the natural world in miniature.

Romanticism and the Sublime

Then came the Romantic era. Artists weren't just painting mountains; they were painting the sublime – that overwhelming feeling of awe, terror, and exhilaration you get standing before something vast, powerful, and uncontrollable, like a storm at sea or a towering peak. Nature became a mirror for intense human emotion and spiritual experience. This led to dramatic compositions, turbulent brushwork, and heightened color palettes. Think of the dramatic skies and turbulent seascapes of J.M.W. Turner, like his powerful The Fighting Temeraire, where the atmosphere and light are as much the subject as the ship itself, or the majestic, idealized American landscapes of Thomas Cole, a key figure in the Hudson River School, whose work like The Oxbow celebrated the grandeur of the American wilderness. Other Hudson River School artists like Frederic Edwin Church and Albert Bierstadt also captured the epic scale of the American landscape with meticulous detail and dramatic light.

![]()

The Barbizon School in France, meanwhile, focused on more intimate, realistic depictions of the forest and rural life, influencing later movements with their direct observation and muted palettes. Their commitment to painting en plein air – directly outdoors – was a crucial step towards capturing the immediate experience of nature, paving the way for Impressionism. The Pre-Raphaelites in England, like John Everett Millais and William Holman Hunt, were also deeply inspired by nature, advocating for a return to detailed observation and painting directly from life, resulting in works with incredibly intricate depictions of flora and fauna, often imbued with symbolic meaning. Millais' Ophelia, for instance, is renowned for its botanically accurate depiction of the plants surrounding the drowning figure, each carrying symbolic weight, demonstrating a fusion of natural detail and narrative symbolism.

Impressionism and the Fleeting Moment

Then came the Impressionists. Oh, the Impressionists! They took their easels outside – literally, embracing plein air painting – to capture the fleeting moments of light and color. It wasn't about perfect detail, but about the impression of a scene. Sunlight on water, the blur of leaves in the wind... they were obsessed with how nature felt in that specific instant. This led to revolutionary techniques like broken brushstrokes, vibrant, unmixed colors, and a focus on capturing atmospheric conditions. Claude Monet's series, like Impression, soleil levant or his famous Water Lilies, capturing the same scene at different times of day and in varying light conditions, are iconic examples of this dedication to light and atmosphere. He painted the same pond over and over, just to see how the light changed! Other Impressionists like Camille Pissarro and Alfred Sisley also dedicated themselves to capturing the changing light and seasons in landscapes, often using similar techniques. Their focus on the transient nature of light was a direct artistic response to the ever-changing character of the natural world.

![]()

Post-Impressionism and Emotional Expression

And what about the Post-Impressionists like Van Gogh? He didn't just paint nature; he painted his experience of it. Those swirling skies and vibrant fields weren't just what he saw, but what he felt. Nature became a vehicle for intense emotion and a unique artistic style. His use of thick impasto and swirling lines conveyed the energy he perceived in the natural world. Think of the emotional intensity in his cypress trees or wheat fields, famously captured in works like The Starry Night or Wheatfield with Cypresses. Paul Cézanne, another key Post-Impressionist, approached landscapes with a focus on structure and form, seeing the geometric shapes underlying natural elements like mountains and trees, influencing later Cubism. Paul Gauguin, too, found profound inspiration in nature, particularly the lush, vibrant landscapes and people of Tahiti. His use of bold, flat colors and simplified forms in works like Vision After the Sermon or his Tahitian paintings explored themes of primitivism, spirituality, and symbolism through the lens of a seemingly unspoiled natural world, offering a stark contrast to the urban focus of many European artists.

![]()

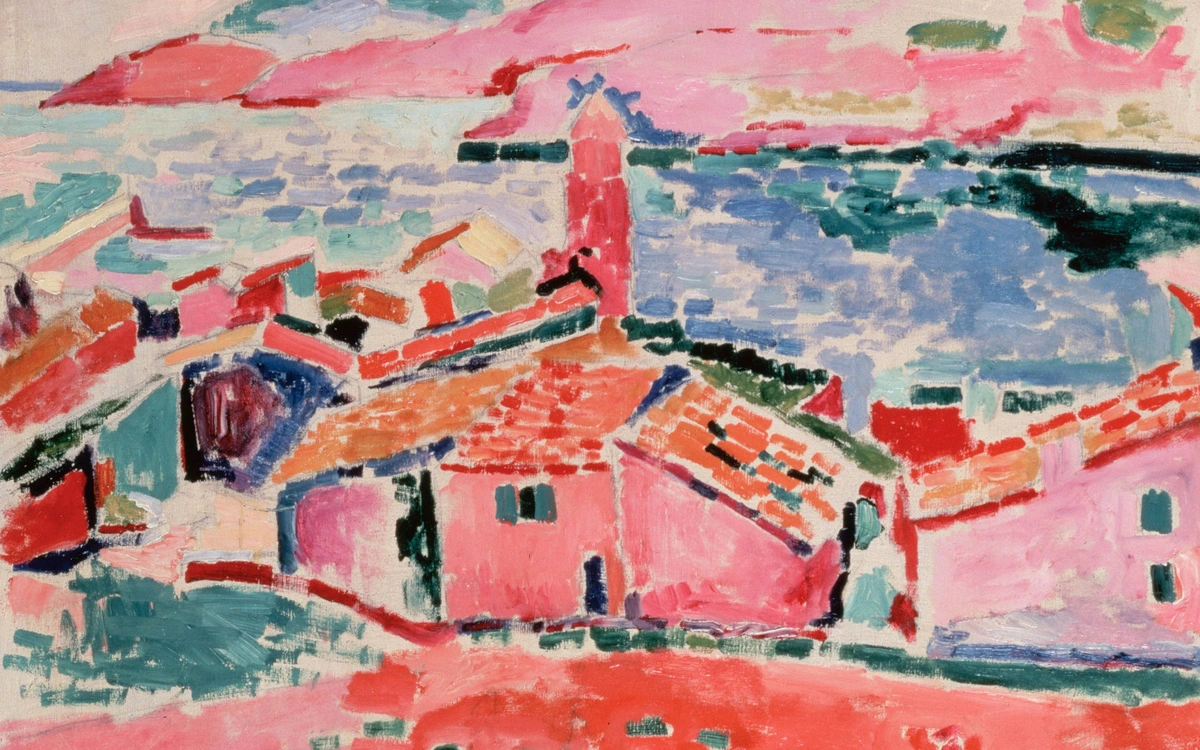

Early Modernism: Fauvism, Expressionism, and Abstract Explorations

Moving into the early 20th century, movements like Fauvism and German Expressionism continued to draw heavily on nature, but often with a focus on subjective experience and emotional intensity rather than objective representation. Fauvists like Henri Matisse used bold, non-naturalistic colors to express their emotional response to landscapes, seeing color as a direct way to convey feeling. Think of the vibrant, almost explosive colors in Matisse's views of Collioure or André Derain's paintings of London. German Expressionists, such as Ernst Ludwig Kirchner or Franz Marc, distorted forms and used intense colors to depict their inner turmoil or spiritual connection to the natural world. Marc's iconic paintings of animals, like Blue Horse I or The Bewitched Mill, used color symbolically to represent emotional states and the spiritual essence of nature. Even as art moved towards abstraction, nature remained a powerful undercurrent. Wassily Kandinsky, a pioneer of abstract art, often spoke of the spiritual connection between art and nature, translating natural rhythms and energies into abstract forms and colors, seeking to evoke the inner 'sound' of the world. Piet Mondrian's early work, like The Red Tree or his series of studies of trees and the sea, shows a clear progression from representational natural forms towards pure abstraction, demonstrating how the underlying structures and energies of nature could be translated into geometric compositions.

![]()

Art Nouveau, Arts and Crafts, and Organic Forms

Moving into the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Art Nouveau drew heavily on nature's forms. This style rejected historical revivalism and embraced organic, flowing lines inspired by plants, flowers, and natural curves like whiplash lines, tendrils, and insect wings. Artists and designers like Alphonse Mucha, Gustav Klimt, and Louis Comfort Tiffany incorporated botanical motifs, insect wings, and flowing water forms into everything from paintings and posters to architecture, furniture, and jewelry, creating a sense of natural elegance and dynamism through decorative, organic patterns. The Arts and Crafts movement, which overlapped with Art Nouveau, also emphasized natural forms and traditional craftsmanship, seeing beauty in the handmade and the organic, often inspired by medieval art and the natural world as a reaction against industrialization. Think of William Morris's intricate textile and wallpaper designs based on flora and fauna.

Symbolism, Surrealism, and the Dreamlike Wild

Nature also played a significant role in Symbolism and Surrealism, albeit often in a more dreamlike or metaphorical way. Symbolist artists used natural elements like flowers, water, or landscapes to evoke moods, ideas, and emotions rather than depict reality, using nature as a symbolic language. Think of the evocative, often melancholic landscapes of artists like Arnold Böcklin. Surrealists, like Salvador Dalí or René Magritte, often placed natural objects in bizarre, unexpected contexts or distorted them to explore the subconscious mind and challenge perceptions of reality. Think of Dalí's melting landscapes or Magritte's apples obscuring faces – nature is present but transformed, serving as a vehicle for the uncanny and the symbolic.

Modern and Contemporary Abstraction

Even in modern art and contemporary art, where abstraction reigns, nature is a powerful undercurrent. Think of Abstract Expressionism – the raw energy, the organic forms, the vastness. It often echoes the feeling of being immersed in a natural force, like the power of a storm or the endless expanse of a landscape. Artists like Jackson Pollock with his drip paintings or Helen Frankenthaler with her soak-stain technique evoke natural processes and landscapes without direct representation, focusing on the fluidity and spontaneity of nature. Wassily Kandinsky, a pioneer of abstract art, often spoke of the spiritual connection between art and nature, translating natural rhythms and energies into abstract forms and colors.

The Influence of Photography

The invention and evolution of photography in the 19th and 20th centuries also profoundly impacted how artists viewed and depicted nature. Photography could capture fleeting moments and intricate details with unprecedented realism, pushing painters to explore different ways of representing the natural world, leading towards Impressionism and abstraction. Photographers themselves, from early landscape pioneers like Carleton Watkins and Ansel Adams to contemporary environmental photographers, have created powerful bodies of work that celebrate, document, and critique our relationship with nature.

Global Perspectives: Non-Western Art and Nature

And let's not forget the influence of non-Western art. Japanese woodblock prints (influence of Japanese woodblock prints on Western art), with their stylized landscapes and depictions of flora and fauna, profoundly impacted Western artists, particularly the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists (Japonisme). Artists like Hokusai and Hiroshige, with their iconic prints of waves, mountains, and everyday scenes, introduced new perspectives on composition, color, and the beauty of everyday scenes, often using techniques like flat areas of color and asymmetrical compositions that felt fresh and dynamic to Western eyes. Beyond Japan, consider the long tradition of Chinese landscape painting (Shanshui), which wasn't just about depicting scenery but capturing the cosmic harmony and energy of nature through expressive brushwork and composition, often leaving significant areas of 'negative space' to evoke mist or emptiness. A classic example is Fan Kuan's Travelers Among Mountains and Streams, which conveys the immense scale and spiritual presence of the natural world. Or the intricate patterns and organic motifs found in Islamic art, often inspired by the geometry and forms of the natural world, particularly in garden design and architectural decoration, using repeating natural elements to create complex, harmonious designs, like the geometric tilework and garden layouts of the Alhambra. Even Indigenous art from various cultures often features deep connections to the land, animals, and natural cycles, serving spiritual, narrative, and aesthetic purposes, frequently using natural materials and depicting local flora and fauna with profound respect and understanding. These global traditions demonstrate that the artistic dialogue with nature is a universal human impulse.

So, from the earliest cave paintings to the meticulous studies of the Renaissance, the emotional outpourings of Romanticism, the fleeting impressions of light, the organic curves of Art Nouveau and the handmade beauty of Arts and Crafts, the symbolic landscapes of Surrealism, and the abstract explorations of modernism, nature has consistently provided artists with both subject matter and a mirror for human experience. But what about today? And what does that historical connection mean for an artist like me? It's a rich legacy that continues to inform and challenge contemporary practice.

Why Nature? An Artist's Personal & Sensory Connection

Okay, enough history for a moment. Let's get personal. Why does nature grab me? Why does it grab so many artists, even today? It's a complex pull, a mix of the tangible and the ineffable. It's not just about finding something pretty to paint; it's about a deeper dialogue. It's about connecting with something ancient and fundamental, something that feels increasingly necessary in our fast-paced, digital lives.

Nature engages all the senses, not just sight. The way light hits a leaf, yes, but also:

- The texture of bark under your fingertips, rough and ancient.

- The sound of rain on leaves, a rhythmic hush, or the sudden crack of thunder.

- The smell of damp earth after a shower, pine needles in a forest, or salt spray by the sea.

- The feeling of wind on your skin, the warmth of sun, the chill of mist.

I remember standing in a dense forest after a rain shower once, the air thick with the scent of pine and wet soil, the light filtering through the canopy in a thousand shades of green. The sounds too – the rustling leaves, the distant bird call, the hum of insects – they created an atmosphere, a feeling of being truly present that I try to capture in the energy of my brushstrokes, even in abstract pieces. Sometimes it's overwhelming, sure, but that's part of the challenge – how to translate that chaos into something coherent, something that captures the feeling. I once tried to capture the smell of a specific coastal walk – the sharp salt, the damp seaweed, the sweet gorse – in a painting. It sounds impossible, right? But by focusing on the colors and textures that evoked those scents for me, using layered washes and rough impasto, I felt I got closer to the memory and feeling of that place than a purely visual depiction ever could. It's a constant reminder that the world is infinitely more complex and vibrant than any single artwork can ever fully convey. I once spent an hour just watching the intricate patterns of moss and lichen on a single rock face – the subtle shifts in color, the delicate textures, the miniature landscape it created. It was a masterclass in detail and complexity, inspiring me to look closer at the world, both macro and micro. And the sheer scale of a mountain range or the endless horizon of the ocean? It simultaneously makes you feel tiny and utterly connected to something immense. That feeling of being a small part of something vast can be incredibly humbling and inspiring.

Nature as Teacher: Lessons in Process, Structure, and Symbolism

Beyond the immediate sensory experience, nature is a profound teacher, offering lessons that resonate deeply with the artistic process and human existence:

- The Ultimate Teacher: Nature teaches you about composition, light, shadow, and color theory better than any textbook. It shows you how things grow, decay, and transform. Observing the way a river carves through rock or how a single flower unfolds its petals reveals fundamental principles of form and process. It's a masterclass in imperfection and change. The constant cycle of growth and decay, the shifting seasons – it's a powerful reminder that nothing is static, and art, too, is a process of evolution. It teaches patience, observation, and the beauty of the transient. I've spent hours just watching how shadows fall across a hillside as the sun moves, or how the color of the sea changes with the light – these are lessons you can't get from a screen. It teaches you to embrace the unexpected, to work with what you're given, much like a sudden change in weather when painting plein air. I remember watching a cliff face slowly erode over years, the way the rock crumbled and shifted, and it made me think about the gradual, sometimes destructive, process of building up and breaking down layers in my own abstract paintings.

- Source of Structure and Pattern: Beyond the obvious beauty, nature is full of hidden structures and mathematical patterns – the spiral of a seashell, the branching of trees, the symmetry of a snowflake, the fractal complexity of coastlines. Artists often draw inspiration from these underlying geometries, whether consciously or unconsciously, finding order within the apparent chaos. These patterns can inform composition, texture, and even abstract forms. Think of the golden ratio found in many natural forms, a principle artists have used for centuries. I find myself often drawn to the repeating patterns in leaves or the chaotic yet ordered structure of tangled branches – trying to capture that underlying logic in my abstract compositions. I remember once being mesmerized by the intricate veins on a fallen leaf, how they branched and subdivided – it felt like a miniature map of the universe, and I spent hours trying to translate that complex, delicate structure into lines and forms in my sketchbook. These natural patterns are a constant source of inspiration for abstract artists seeking to create dynamic yet harmonious compositions.

- Nature as Metaphor and Symbol: Nature provides a rich language of symbols and metaphors that artists use to explore human emotions and experiences. A storm can represent inner turmoil, a blooming flower can symbolize hope or fleeting beauty, a gnarled tree can speak of resilience or age. My own work, while often abstract, frequently uses colors and forms inspired by natural phenomena to evoke specific feelings or states of being – the calm of a still lake, the energy of a thunderstorm, the quiet contemplation of a forest floor. It's about translating the external world into an internal, emotional landscape. Beyond simple representation, nature offers a deep well of symbolic meaning that resonates across cultures and time, allowing artists to communicate complex ideas about life, death, transformation, and the human condition.

Nature's Elements, Techniques, and the Spirit of Place

Artists often focus on specific elements of nature, finding unique inspiration in their characteristics and the feelings they evoke. This focus also influences the techniques they employ and how they capture the unique 'spirit of place' (genius loci) of a location. Understanding these elements can offer a deeper appreciation for nature-inspired art. Here's a look at how different elements translate into artistic approaches:

Element | Characteristics & Feelings Evoked | Techniques & Artistic Approaches | Key Artists/Examples | Spirit of Place Connection |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Light & Shadow | Transient, mood-setting, reveals form, dramatic or subtle | Chiaroscuro, sfumato, atmospheric perspective, capturing specific times of day (dawn, dusk), Impressionism's focus on fleeting light, using glazes or washes to build light | Claude Monet, J.M.W. Turner, Rembrandt, Caravaggio, Johannes Vermeer, James Turrell (installations) | Defines the visual character and mood of a location (e.g., sharp desert light vs. misty forest light), evokes specific times of day or weather conditions |

| Water | Movement, reflection, color, calm or powerful, flow, subconscious | Glazing (translucency), impasto (texture of waves), capturing reflections, using fluid mediums like watercolor or ink, wet-on-wet techniques, depicting ripples or currents | J.M.W. Turner, Claude Monet (Water Lilies), Hokusai (The Great Wave), David Hockney (pools), contemporary artists using water installations or video | Reflects the energy and mood of a place (serene lake, turbulent ocean, rushing river), symbolizes flow, change, or depth |

| Earth & Rock | Grounding, permanence, texture, deep time, resilience | Textured brushwork, palette knives, incorporating actual materials (sand, earth, pigments), depicting geological forms and colors, carving, sculpting, using earth pigments | Cézanne (Mont Sainte-Victoire), Ansel Adams (photography), Land Artists like Robert Smithson or Andy Goldsworthy, Ursula von Rydingsvard (wood sculpture), Richard Long (walks/sculptures) | Conveys the stability, age, and physical presence of the land (rugged mountains, fertile soil, rocky coast), connects to history and deep time |

| Trees & Forests | Life, growth, endurance, mystery, solitude, hidden aspects | Depicting bark/leaf textures, dappled light, capturing density or airiness, using trees symbolically, expressive lines for branches, etching, woodcuts, exploring root systems | Barbizon School artists, Caspar David Friedrich, Gustav Klimt (Symbolism), Emily Carr (Pacific Northwest forests), contemporary artists exploring forests as ecosystems or using wood as medium | Defines the visual and atmospheric character (dense woods, open groves), evokes feelings tied to specific forest types, symbolizes life cycles or hidden worlds |

| Sky & Weather | Vastness, mood, fleeting moments, drama, external/internal states | Color mixing for clouds/sunsets, atmospheric perspective, capturing specific weather events (storms, fog), expressive brushwork, layering glazes, using soft pastels or watercolors for atmospheric effects | J.M.W. Turner, Vincent van Gogh (Starry Night), John Constable, contemporary photographers capturing extreme weather, Olafur Eliasson (installations mimicking weather) | Sets the emotional tone and scale of a landscape, reflects the climate and transient conditions, can mirror internal emotional states |

| Flora & Fauna | Life, fragility, adaptation, interconnectedness, intricate detail | Detailed illustration, expressive depictions, symbolic use, abstract forms from organic shapes, wildlife painting, botanical studies, macro photography, using natural dyes or materials | Albrecht Dürer, Pre-Raphaelites (Millais), John James Audubon (illustrations), contemporary Bio Artists or wildlife photographers, Georgia O'Keeffe (flowers/bones) | Represents the unique biodiversity and life force of a place, adds narrative or symbolic layers, connects to themes of life, death, and adaptation |

Capturing the Spirit of Place (Genius Loci)

Beyond these elements, the specific geography and climate of a region profoundly influence the art created there. Think of the unique light of the Mediterranean that captivated artists like Van Gogh and Matisse, leading to vibrant color palettes. Or the vast, open skies and dramatic rock formations of the American West that defined the Hudson River School, or the way Georgia O'Keeffe captured the stark, spiritual landscape of New Mexico, focusing on bones and flowers to represent its essence. The misty landscapes of East Asia, the dense jungles of the tropics, the stark beauty of polar regions, or the vibrant colors of a coral reef each offer distinct visual languages and inspire different artistic approaches and techniques. Capturing this regional essence, this 'spirit of place' (or genius loci), is a key goal for many nature-inspired artists. It's about conveying not just what a place looks like, but what it feels like, its history, its atmosphere, its unique energy. Artists achieve this through careful observation, immersion in the environment, and selecting elements and techniques that resonate with that specific location.

Artists also draw inspiration from the materials nature provides. Natural pigments derived from minerals and plants have been used for millennia. Charcoal from burnt wood is a fundamental drawing tool. Artists might incorporate sand, earth, or even dried leaves and flowers into their work, directly connecting the artwork to the physical environment. This use of natural materials can add texture, color, and a deeper conceptual layer to the piece.

Contemporary Artists and Nature: New Perspectives, Urgent Themes

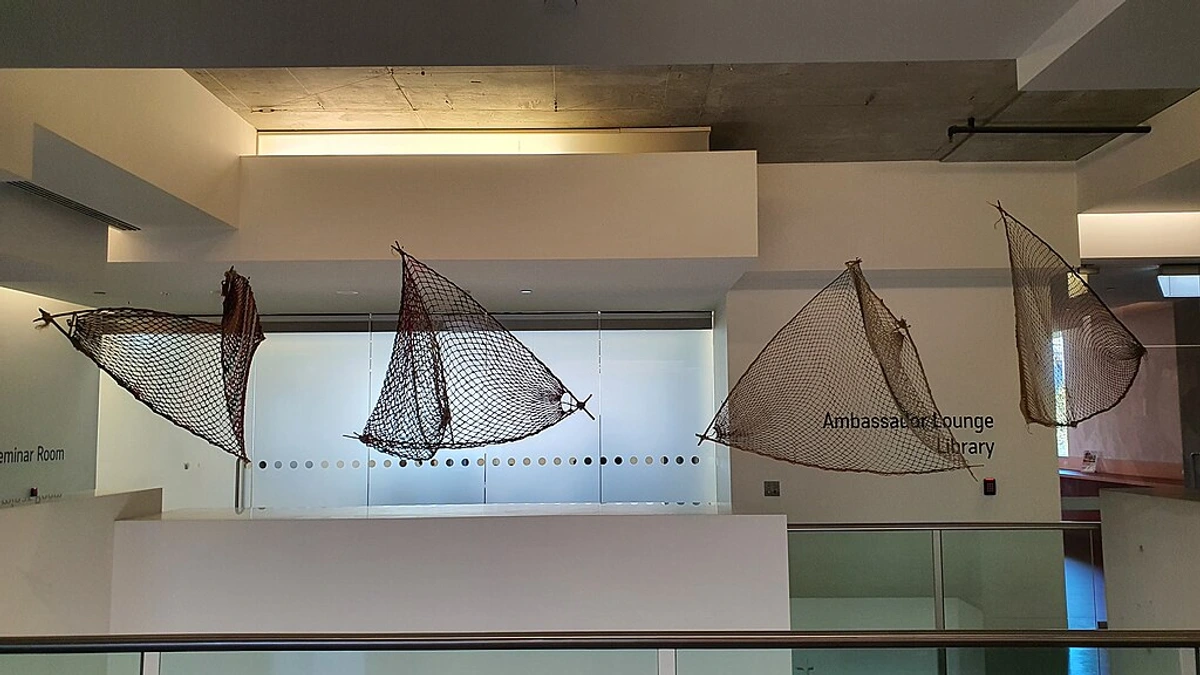

Nature continues to be a vital source for artists today, often with new perspectives, particularly in light of growing environmental concerns. Land Art (or Earth Art) emerged in the late 1960s, where artists used the natural landscape itself as their medium, creating large-scale interventions like Robert Smithson's Spiral Jetty or Andy Goldsworthy's ephemeral sculptures made from natural materials. This movement blurred the lines between art and environment, often highlighting the scale and transient nature of the land.

More recently, Environmental Art directly addresses ecological issues, using nature as both inspiration and subject matter to raise awareness about climate change, conservation, and humanity's impact on the planet. Artists might use natural materials, work directly in affected landscapes, or create pieces that highlight environmental concerns. For example, artists like Olafur Eliasson create installations that mimic natural phenomena or use natural materials to make viewers confront environmental issues, such as his Ice Watch installation where glacial ice blocks were displayed in public spaces to melt. Maya Lin, known for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, also creates powerful environmental sculptures that engage with the landscape and its history, often addressing themes of conservation and memory. Chris Jordan's photography, documenting the vast scale of consumer waste, is another powerful example of art addressing environmental issues. Some artists even engage in Bio Art, working with living organisms, biological processes, or ecological systems as their medium, creating pieces that explore themes of life, growth, decay, and humanity's relationship with the biological world in a very direct and sometimes challenging way, like artworks grown from mycelium or bacteria.

Beyond traditional mediums, contemporary artists also use nature as a basis for performance art or ephemeral installations. Think of artists who create temporary sculptures out of ice or leaves that are designed to melt or decompose, highlighting the transient nature of both art and the environment. Others might use their own bodies interacting with the landscape in performances that speak to connection, vulnerability, or the impact of human presence. These forms of art are inherently linked to the natural cycles of change and decay, offering a powerful commentary on time and environmental fragility.

But contemporary nature-inspired art isn't limited to these movements. Photographers capture the raw beauty and fragility of landscapes and wildlife, often highlighting the impact of human activity. Artists like Ansel Adams or more contemporary photographers like Edward Burtynsky (documenting human impact on the earth) and Sebastião Salgado (documenting global social and environmental themes) continue this tradition. Sculptors use natural materials like wood, stone, or even ice, or create forms inspired by organic shapes – Ursula von Rydingsvard's large-scale wooden sculptures evoke natural forms and textures, while Martin Puryear's work often uses wood and organic shapes to explore complex themes. Digital artists explore natural patterns through algorithms or create immersive virtual natural environments. Abstract painters continue to draw from nature's textures, colors, and energies, translating the feeling of a place or phenomenon into non-representational forms. My own art for sale, for instance, often uses color and form to evoke the feeling of landscapes or natural phenomena, even if it's not a direct depiction. It's about capturing that sensory or emotional response nature triggers. It feels like trying to bottle the energy of a storm or the quiet hum of a forest.

Technology has also opened new avenues for nature-inspired art. Artists use data visualization to represent environmental changes, create digital simulations of natural processes, or even incorporate biological data into their work. Generative art, for example, can use algorithms based on plant growth patterns (like L-systems) to create complex, organic visual forms. Drones allow for breathtaking aerial photography and videography of landscapes, offering new perspectives on scale and form. GIS data can be used to map environmental issues and inform site-specific installations. Photography and video art capture natural phenomena in ways previously impossible, allowing for new forms of expression and interaction with the natural world, and can be powerful tools for highlighting environmental issues.

Nature, Ethics, and Environmental Responsibility

As our understanding of environmental challenges deepens, so too does the role of artists in addressing them. Nature-inspired art today often carries an ethical dimension, prompting viewers to consider their relationship with the planet. This can manifest in several ways:

- Raising Awareness: Many artists use their work to directly highlight environmental degradation, climate change impacts, or species loss. Their art serves as a visual commentary, making abstract scientific data or distant problems feel immediate and personal. For example, the work of Chris Jordan uses large-scale images of consumer waste to confront viewers with the sheer scale of environmental impact.

- Sustainable Practices: Artists are increasingly exploring the use of eco-friendly materials and processes, minimizing their own environmental footprint in their practice. This can involve using natural pigments, recycled materials, or creating works that are biodegradable. For me, thinking about the materials I use and their impact is becoming increasingly important. It's a small step, but it feels necessary. Some artists even create works designed to decompose naturally, returning to the earth.

- Site-Specific Commentary: Working directly in affected landscapes allows artists to create powerful, site-specific pieces that draw attention to local environmental issues, whether it's pollution, habitat destruction, or the effects of extreme weather. Land Art and Environmental Art often operate in this space.

- Promoting Connection and Stewardship: By celebrating the beauty and complexity of the natural world, artists can foster a deeper emotional connection in viewers, inspiring a sense of care and responsibility towards the environment. This aligns with concepts like Biophilia, the innate human tendency to connect with nature. Art can remind us what we stand to lose.

This ethical turn in nature-inspired art reflects a growing urgency and a recognition that the relationship between humanity and nature is not just aesthetic or spiritual, but also one of profound responsibility. Art becomes a tool for advocacy, reflection, and imagining a more sustainable future.

The Challenges of Capturing Nature

Working directly in nature, whether through plein air painting, creating Land Art, or gathering materials, presents unique challenges and rewards. You're at the mercy of the elements, forced to work quickly or adapt. The weather is unpredictable – wind, rain, changing light can be frustrating obstacles. Insects can be a nuisance, and simply carrying supplies can be physically demanding. Capturing the dynamic, ever-changing nature of a scene in a static medium like paint or sculpture is a constant challenge; the light shifts, the water moves, the moment is gone almost as soon as you try to capture it. It forces you to be adaptable and embrace imperfection. I remember one time trying to paint a sunset over the sea, and the colors were changing so rapidly, I felt like I was in a race against time, frantically trying to mix paints before the light vanished. It was exhilarating and utterly frustrating! And yes, sometimes you just get dirt in your paint, or a bug lands on your wet canvas. Or, my personal favorite, setting up your easel only to realize you've forgotten your water container... or your brushes. It's a powerful lesson in embracing imperfection and the uncontrollable. Oh, and the time a seagull decided my carefully arranged still life of beach treasures was actually a snack bar? That was... memorable. And messy.

But you gain an immediacy, a direct sensory input that's hard to replicate in the studio. There's a humility in collaborating with the wind, the rain, or the tide – a reminder that you are part of, not separate from, the natural world. Working in the landscape, especially with Land Art, also involves navigating permissions, site-specific challenges, and the often ephemeral nature of the work itself, which is designed to change or decay over time.

Bringing the Outside In: Nature-Inspired Art in Your Space

So, how does this translate for you, maybe someone looking to bring some of that natural magic into your own space? Buying art inspired by nature is a fantastic way to do it. It's not just about hanging a landscape painting (though those are great!); it's about choosing pieces that evoke the feeling of nature, creating a connection to the wild even indoors. It's part of the idea behind Biophilic Design – the concept that humans have an innate need to connect with nature, and bringing elements of the natural world into built environments can improve well-being. Art is a perfect way to do this, offering a visual and emotional bridge to the calming and restorative power of the outdoors.

Think about the specific elements that resonate with you. Do you love the calm of a forest? The energy of the ocean? The intricate detail of a single leaf? This can guide your search. Consider how different art forms capture these feelings:

- Abstract pieces can capture the energy of a storm or the quiet calm of a forest floor, using color and form to evoke mood and atmosphere without literal representation. Think of swirling blues and grays for a storm, or layered greens and browns for a forest floor. An abstract painting might use gestural brushstrokes to mimic the movement of wind or water, or explore the fractal patterns found in nature. Abstract art is particularly good at capturing the essence or feeling of nature rather than its literal appearance. I have a piece in my own home, an abstract painting inspired by the colors of a stormy sea, and just looking at it brings back the feeling of that raw, powerful energy, even on a calm day.

- Textile art can mimic organic textures and patterns, bringing tactile natural elements indoors. Weavings, tapestries, or fiber sculptures can evoke the feel of moss, bark, or flowing water, adding a unique, soft dimension. Artists might use natural dyes or fibers to enhance this connection. Textiles are great for adding warmth and texture, mirroring the tactile experience of nature.

- Sculptures can use natural materials (wood, stone, clay) or forms inspired by nature (trees, animals, geological shapes). A smooth stone sculpture might evoke the feeling of river rocks, while a carved wooden piece could suggest the growth and form of a tree. Sculptures can also capture the dynamic energy of natural forces, like wind or water erosion, or the solid permanence of rock. They bring a three-dimensional presence that connects to the physical reality of nature.

- Photography can transform a simple natural scene into something profound, capturing fleeting moments of light, dramatic landscapes, or intimate details of flora and fauna. A stunning photograph can transport you to a mountain peak or a quiet forest path, offering a window to the outside world. Environmental photography, in particular, can bring urgent ecological themes into your space. Photography excels at capturing specific moments and details with incredible realism or artistic interpretation.

- Botanical illustrations or detailed studies of flora and fauna bring the precision and beauty of individual organisms into focus. These pieces celebrate the intricate design found in nature, perfect for adding a touch of scientific beauty and historical elegance. They highlight the delicate complexity of the natural world.

- Art made from natural materials (like found object art using driftwood, leaves, or stones) directly connects your space to the environment, bringing a piece of the outdoors inside in a literal way. These pieces often tell a story of place and time, incorporating the textures and colors of the natural world itself. They offer a tangible link to the earth.

Think about the mood you want to create. Do you want the vibrant energy of a summer meadow or the serene calm of a winter forest? Nature-inspired art offers a huge range of possibilities. Consider the scale of the artwork in relation to your space – a large landscape can create a sense of vastness, while a small, detailed botanical print invites close observation. The color palette of the piece will also significantly impact the room's atmosphere; cool blues and greens can be calming, while warm reds and oranges can add energy, much like the colors found in nature itself. It's also a way to connect your indoor space to the world outside, creating a sense of harmony and peace. And honestly, who doesn't need a little more well-being these days? It's like bringing a piece of that calming forest walk or invigorating mountain hike home with you. Nature-inspired art is also increasingly found in public and corporate spaces, like hospitals, offices, and airports, specifically chosen for its calming and restorative qualities, demonstrating its recognized therapeutic benefits.

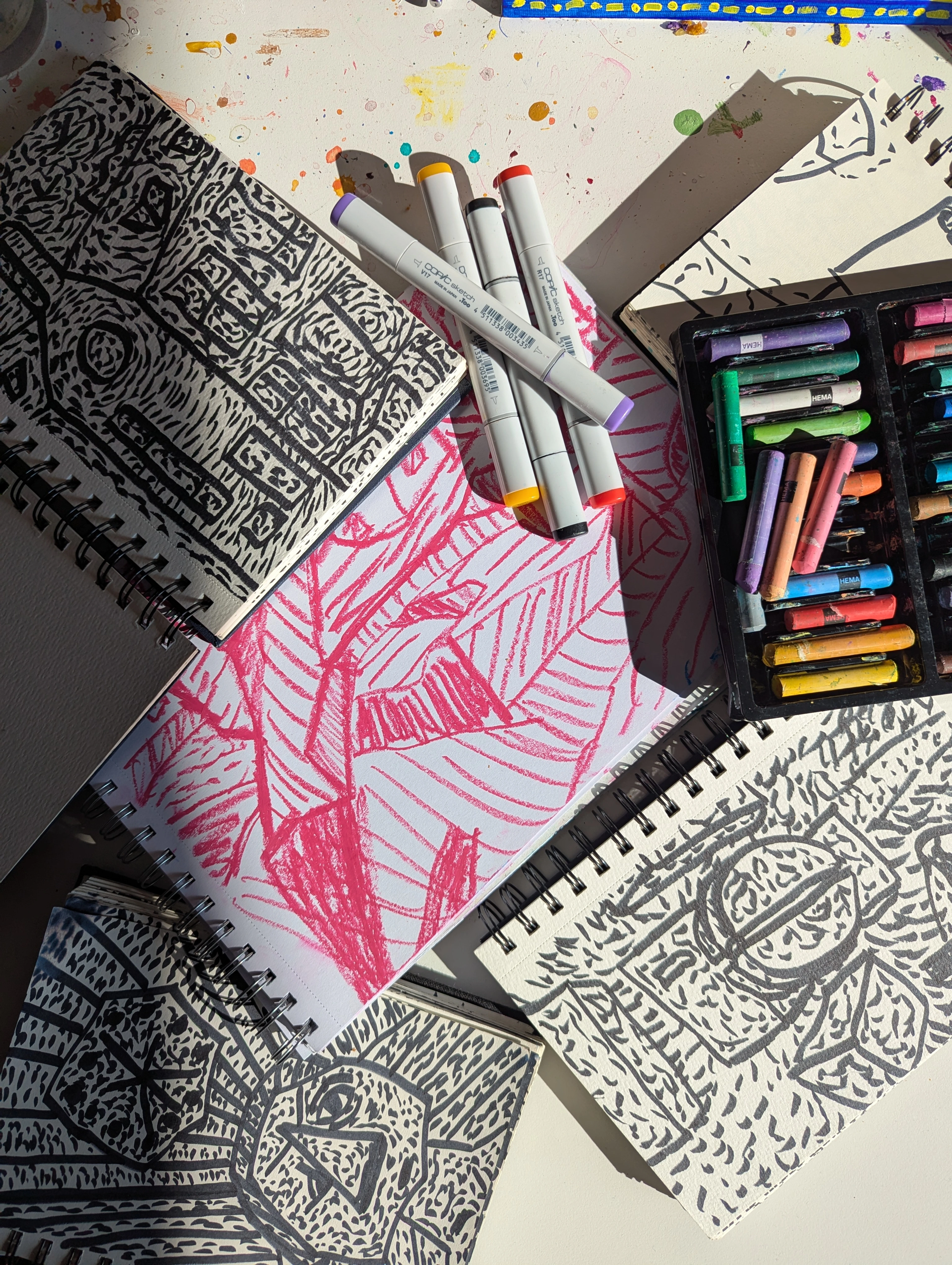

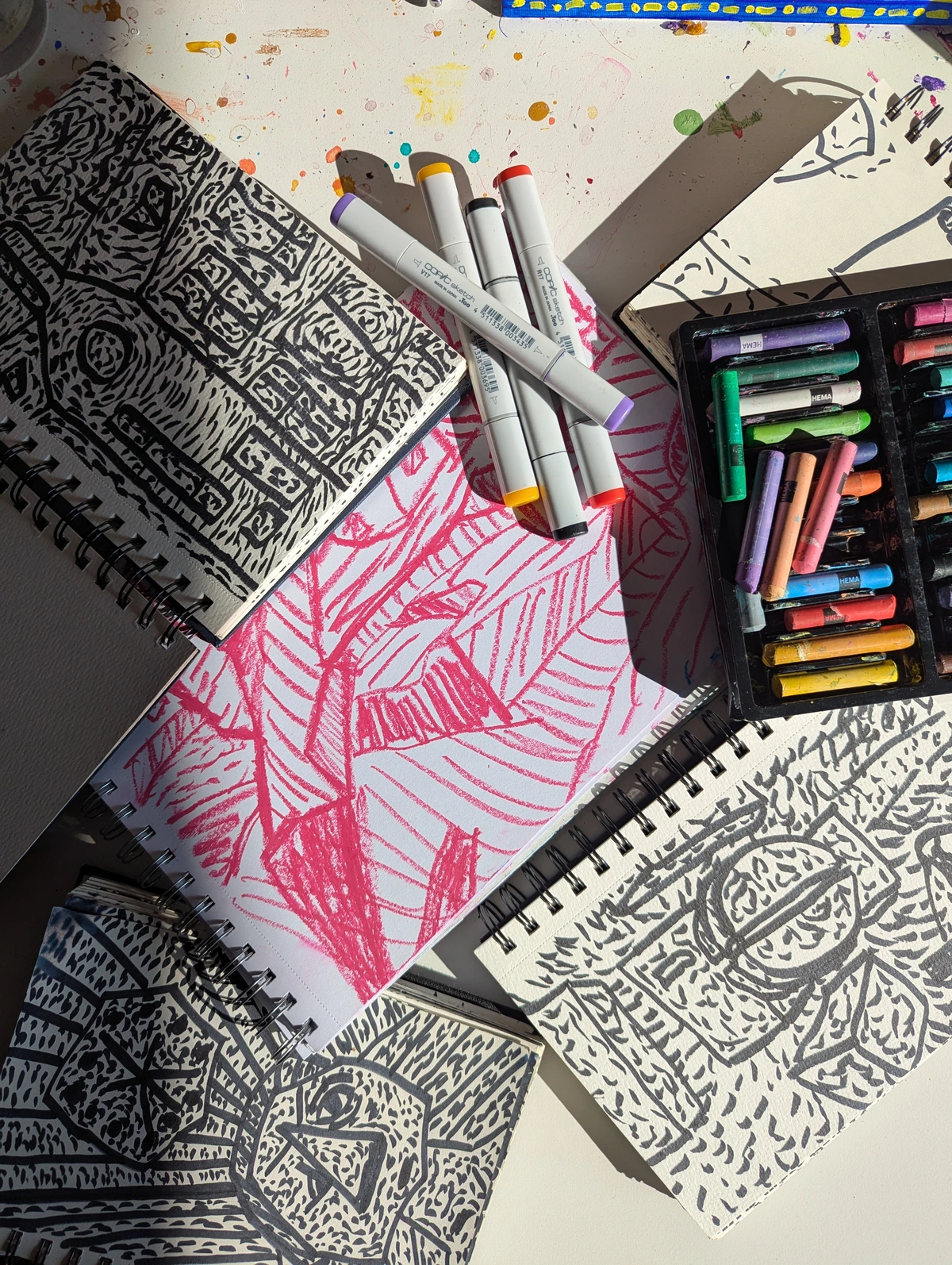

For Fellow Artists: Finding Your Nature Connection

If you're an artist yourself looking for inspiration, try dedicating time specifically to observing nature. Sketch outdoors, collect interesting leaves or stones, focus on capturing the feeling of a place rather than just its appearance. How does the wind sound? What does the air smell like after rain? These sensory details can unlock new creative pathways. Don't be afraid to experiment with different techniques – try using thick impasto for the texture of bark, or thin glazes for the translucence of water. Plein air painting is a classic way to immerse yourself, but even sketching from a window can be a start. Try specific exercises like blind contour drawing of a plant to really focus on its form, or quick gesture sketches of trees swaying in the wind to capture movement. Spend 10 minutes drawing the same tree at different times of day to observe how the light changes it. Create a color palette based only on colors observed in a 1-square-foot patch of ground. Consider working with natural materials you find, or creating ephemeral art in nature itself, letting the environment shape your process. And don't forget urban nature – the resilience of a weed pushing through concrete, the way light hits a fire escape covered in vines, the wildlife that adapts to city life. There's inspiration everywhere, even in the cracks in the pavement. Keeping a dedicated nature-focused sketchbook or journal can be invaluable for capturing these fleeting observations, sensory details, and abstract ideas before they fade.

If you're curious about adding some nature-inspired pieces to your collection, maybe start by exploring art for sale online or visiting local art galleries. See what speaks to you. What piece reminds you of a favorite place, a cherished memory, or just makes you feel good? It's a wonderful way to start collecting art.

FAQ: Artists and Nature

Here are a few common questions I hear about artists and their connection to nature:

- Is all landscape art inspired by nature? Yes, broadly speaking, but the way it's inspired varies hugely. Some aim for realism, others use nature as a starting point for abstraction or emotional expression. Landscape art is a broad genre that has evolved significantly over time.

- Do artists only paint pretty nature scenes? Absolutely not! Nature can be harsh, wild, and even terrifying. Artists explore all facets, from serene beauty to natural disasters and decay. The sublime in Romanticism, for example, embraced the terrifying power of nature.

- Can abstract art be inspired by nature? Definitely! Abstract artists often draw inspiration from natural patterns, textures, colors, and energies without directly representing objects. Think of the flow of water, the structure of a leaf, or the chaos of a forest. Abstract art is a powerful way to capture the essence of nature and the artist's emotional response to it.

- Are there specific art movements focused on nature? While many movements feature nature prominently (Romanticism, Impressionism, Hudson River School, Pre-Raphaelites, Art Nouveau, Arts and Crafts, Fauvism, Expressionism), movements like Land Art (or Earth Art) and Environmental Art specifically use the natural landscape itself as the medium and site for the artwork, or address ecological themes and conservation. Bio Art also engages directly with living systems.

- How can I find nature-inspired art to buy? Look in galleries, online marketplaces (buying art online), and artist websites. Consider different types of artwork like paintings, prints, photography, sculpture, and textiles. Think about the feeling you want the art to evoke and research artists who work with nature themes. Nature-inspired art is widely available across various price points.

- What techniques do artists use to capture nature? Artists use a vast array of techniques, from detailed observation and realistic rendering to expressive brushwork, abstract forms, and working directly with natural light or materials. Plein air painting is a classic technique for capturing the immediate experience of being outdoors, while techniques like impasto, glazing, and specific color palettes are used to convey texture, light, and atmosphere. Using natural materials like earth or charcoal also connects the technique directly to the source.

- Can creating nature-inspired art be therapeutic? Absolutely. The act of observing nature and translating its forms, colors, and feelings into art can be incredibly grounding and meditative, offering a way to connect with the world and process emotions. It's a form of art therapy that connects you to the physical world.

- What specific types of nature inspire different kinds of art? Different environments resonate with different artists and movements. Forests might inspire introspection or detailed studies, mountains evoke the sublime and scale, urban nature can explore themes of adaptation and human impact, while the sea inspires works about power, change, and the unknown. Deserts might inspire stark minimalism or explorations of resilience, while wetlands could lead to studies of complex ecosystems and reflections. It really depends on the artist's focus and feeling, and the unique characteristics of the landscape.

- How has technology influenced nature-inspired art? Technology has opened new avenues, from digital photography and video art capturing natural phenomena in new ways, to using algorithms to generate nature-inspired patterns, or creating immersive virtual reality experiences of natural environments. It allows for new forms of expression and interaction with the natural world, and can also be powerful tools for highlighting environmental issues.

- What are some challenges artists face when working with nature? The weather is unpredictable (wind, rain, changing light!), insects can be a nuisance, carrying supplies can be difficult, and capturing the dynamic, ever-changing nature of a scene in a static medium is a constant challenge. It forces you to be adaptable and embrace imperfection. Working in the landscape, especially with Land Art, also involves navigating permissions, site-specific challenges, and the often ephemeral nature of the work itself.

- How do artists use nature to raise environmental awareness? Many contemporary artists use their work to directly comment on environmental issues. This can involve documenting pollution or habitat loss through photography or film, creating installations using waste materials, making ephemeral art that highlights the fragility of ecosystems, or using natural processes (like erosion or growth) as part of the artwork itself to illustrate ecological concepts or concerns. Environmental Art and Bio Art are particularly focused on these themes.

- What's the difference between painting from nature and painting about nature? Painting from nature typically involves direct observation, often outdoors (plein air painting), focusing on capturing the visual appearance, light, and atmosphere of a specific scene. Painting about nature is broader; it might be inspired by memories, emotions, scientific understanding, or conceptual ideas related to nature. It can be abstract, symbolic, or address themes like environmentalism, using nature as a subject or metaphor rather than just a visual reference.

- How does nature inspire abstract artists? Abstract artists find inspiration in nature's underlying structures, patterns (like fractals or spirals), textures (bark, rock, water), colors, and energies. They translate these elements into non-representational forms, lines, and colors to evoke the feeling or essence of a natural phenomenon or landscape, rather than depicting it literally. It's about capturing the rhythm, flow, or raw power of nature through abstract means.

- What is the future of nature-inspired art, especially with climate change? The future of nature-inspired art is increasingly intertwined with environmental concerns. Artists will likely continue to use nature as a subject, but also as a medium, a site for intervention, and a platform for activism and awareness. Art about nature will likely focus more on themes of climate change, conservation, resilience, and humanity's relationship with a changing planet, using both traditional and new technologies to explore these urgent issues.

- Is nature-inspired art popular or commercially viable today? Yes, absolutely. Nature remains a universally appealing theme, and art inspired by nature, from traditional landscapes to abstract interpretations and environmental pieces, continues to be popular with collectors and viewers. Its ability to evoke feelings of calm, connection, or awe ensures its enduring commercial viability across various styles and mediums.

- How does the emotional or spiritual connection to nature manifest in art? This connection often manifests through the artist's choice of subject, color palette, brushwork, and overall mood. Romanticism, for example, directly sought to capture the spiritual sublime. Abstract artists might use color and form to convey the feeling of awe or peace experienced in nature. The use of natural materials can also be a way to express a spiritual connection to the earth. It's a deeply personal aspect that infuses the artwork with feeling.

- How do artists capture the sounds or silence of nature? While visual art is primarily about sight, artists can evoke sound or silence through various means. This might involve using specific textures or patterns that suggest rustling leaves or rippling water, employing color palettes that create a sense of calm or stillness, or using composition to create a feeling of vast, empty space. Some contemporary artists also incorporate actual sound recordings or create installations that interact with natural sounds.

- What is the concept of 'Spirit of Place' (Genius Loci) in nature-inspired art? 'Spirit of Place' refers to the unique atmosphere, character, and history of a specific location. Artists capturing this aim to convey not just its visual appearance but its intangible essence – the feeling it evokes, its cultural significance, or its ecological story. It's about creating art that is deeply rooted in and responsive to a particular environment.

- How does memory and imagination play a role in nature-inspired art? Artists often draw on memories of natural places or experiences, sometimes combining them with imagination to create idealized, symbolic, or entirely invented landscapes. This allows nature to be a muse even when the artist is not physically present in the environment, fueled by reflection, longing, or the desire to explore internal landscapes inspired by the external world.

Conclusion: The Enduring Call of the Wild

For artists, nature isn't just a subject; it's a partner in the creative process. It provides the raw material, the inspiration, and the quiet space needed for reflection. It challenges us, comforts us, and constantly reminds us of the incredible complexity and beauty of the world we inhabit. It's a wellspring that never runs dry, constantly offering new perspectives and challenges. The cycles of nature, the constant change and renewal, mirror the artistic process itself – moments of intense creation, periods of quiet contemplation, and the inevitable transformation of ideas. For me, the dialogue with nature is ongoing, a source of both profound peace and restless energy that fuels my work. It's the quiet hum beneath the surface of every brushstroke, the echo of a storm in the texture, the memory of light in the color.

Whether you're an artist yourself, a collector, or just someone who appreciates the power of a great piece of art, the connection between creativity and the natural world is undeniable. It's a conversation that has been happening for centuries, across cultures and continents, and one that will continue as long as there are artists to look, and nature to inspire – perhaps now more urgently than ever, as we grapple with our impact on the planet. It's a relationship that grounds us, challenges us, and ultimately, enriches our lives and our art.

So next time you're feeling stuck, overwhelmed, or just in need of a little creative spark, maybe step outside. Look closely at a leaf, watch the clouds drift, or listen to the wind in the trees. You never know what ideas might take root.

Interested in seeing how nature inspires contemporary artists? Explore my own art for sale or learn more about my artist journey.

If you're in the Netherlands, consider visiting my museum in 's-Hertogenbosch to see some of my nature-inspired work in person.