Found Object Art: Why Artists Transform Discarded Items & Objet Trouvé Explained

Explore the world of found object art ('objet trouvé') with an artist. Discover its history, the creative process, challenges, and why discarded items become powerful art. Learn how to appreciate and even create your own, seeing potential everywhere.

The Art of the Unexpected: Why Artists Use Found Objects

Let's be honest. We all have that drawer. You know the one. The one filled with random bits and bobs – a single button, a strange key, a broken toy piece, maybe a dried-up pen that might still work. We keep them, sometimes for a reason, sometimes just because we can't quite bring ourselves to throw them away. There's a tiny, almost imperceptible story attached to each one. I remember finding a smooth, sea-worn piece of glass on a beach once and feeling an immediate connection, wondering about its journey. It wasn't 'art,' but it held a certain magic, a hidden potential. It felt like a secret whispered just to me.

Now, imagine taking that drawer, spilling it out, and seeing not just clutter, but potential for art. That's a little glimpse into the mind of an artist who uses found objects. It's a fascinating world, one that challenges our notions of value, beauty, and what art can even be. And if you've ever looked at a pile of junk and felt a flicker of something more, you're already halfway there. It's a practice that often feels like a treasure hunt, full of serendipity and unexpected discoveries. For me, it's about seeing the world differently, finding beauty and meaning where others see only trash. It's a skill I try to cultivate in my own work, even when I'm just mixing paint in my studio or looking for interesting textures for a print. It's about being open to the unexpected. I once found a perfectly rusted piece of metal just lying on the side of the road and immediately saw the potential texture it could add to a piece – it felt like a gift from the universe, waiting just for me.

What Exactly Are Found Objects in Art? (The Fancy Term: Objet Trouvé)

In the art world, we often use the term objet trouvé, which is just fancy French for "found object." Simple, right? But the concept is profound. It's about taking something that wasn't created as art – an everyday item, a discarded piece of junk, a natural object – and presenting it as art, often with little or no modification. It's a concept that immediately raises the question: is this really art? And that's precisely the point. It forces us to reconsider our definitions of what art is.

This wasn't always a thing, at least not in the formalized way we think of it today. For centuries, art was largely about skill, craftsmanship, transforming raw materials (paint, clay, marble) into something beautiful or meaningful. Yet, the human impulse to collect and repurpose has always been there, visible in folk art, traditional crafts, or even just the way people have historically made do with what they had. The seeds of using non-traditional materials in a fine art context were perhaps sown earlier, in movements like Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, where artists began experimenting with visible brushstrokes, texture, and less idealized subjects. This subtle shift away from pure illusionistic representation and towards the materiality of the artwork itself – acknowledging the paint, the canvas, the surface as important elements – paved the way for more radical material choices down the line. It was a quiet rebellion, perhaps, but a crucial one.

Then came the early 20th century, and movements like Dadaism and Surrealism took this idea and ran with it. Artists associated with these movements were deliberately trying to disrupt traditional art practices and challenge societal norms. Using everyday, often mass-produced, objects was a perfect way to do that. Dada, born out of the disillusionment of WWI, was inherently anti-art and anti-bourgeois; presenting a urinal as art was the ultimate slap in the face to the established art world and its values. Surrealism, exploring the subconscious, found resonance in the strange juxtapositions and inherent histories of found items. It was a bit of a rebellious idea, shaking up the traditional art world. And honestly? I love that. It feels very... human. Like finding a cool rock on the beach and knowing, just knowing, it's special, even if it's just a rock.

Before these movements fully embraced the found object, Cubism played a crucial role. Artists like Picasso and Braque began incorporating newspaper clippings, wallpaper, and other bits of reality into their collages. This wasn't just about adding texture; it was about breaking down traditional representation and incorporating fragments of the real world into the artwork's surface, blurring the lines between painting and reality. This direct use of everyday materials in a fine art context was a vital step, paving the way for the more conceptual uses of found objects in later movements like Dada.

It's worth noting the subtle but important distinctions between terms you might hear:

- Found Object (objet trouvé): The item itself, selected by the artist. Think of a piece of driftwood.

- Readymade: A specific type of found object, usually mass-produced, presented as art with minimal or no alteration, emphasizing the conceptual act of selection (e.g., Duchamp's urinal, Fountain).

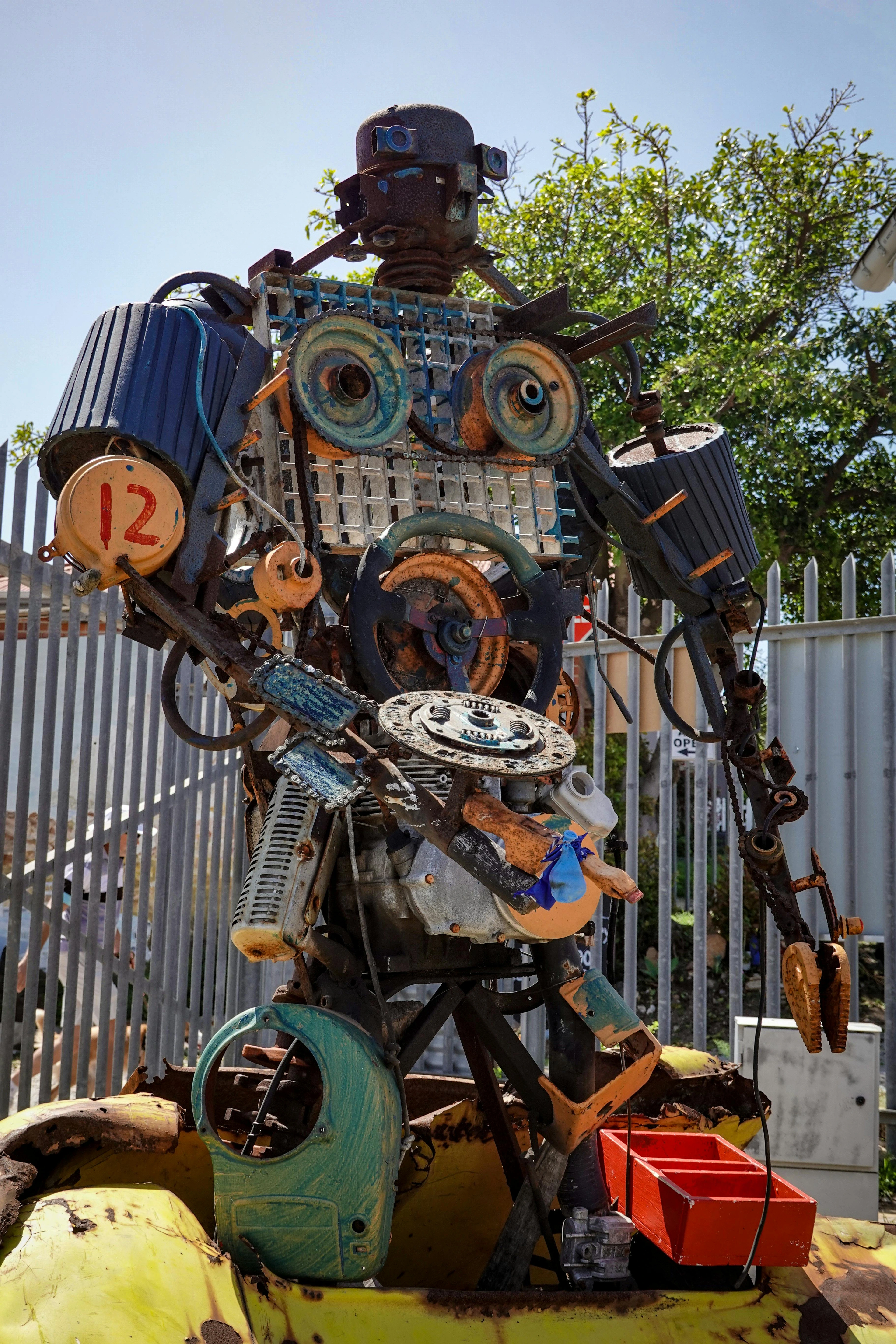

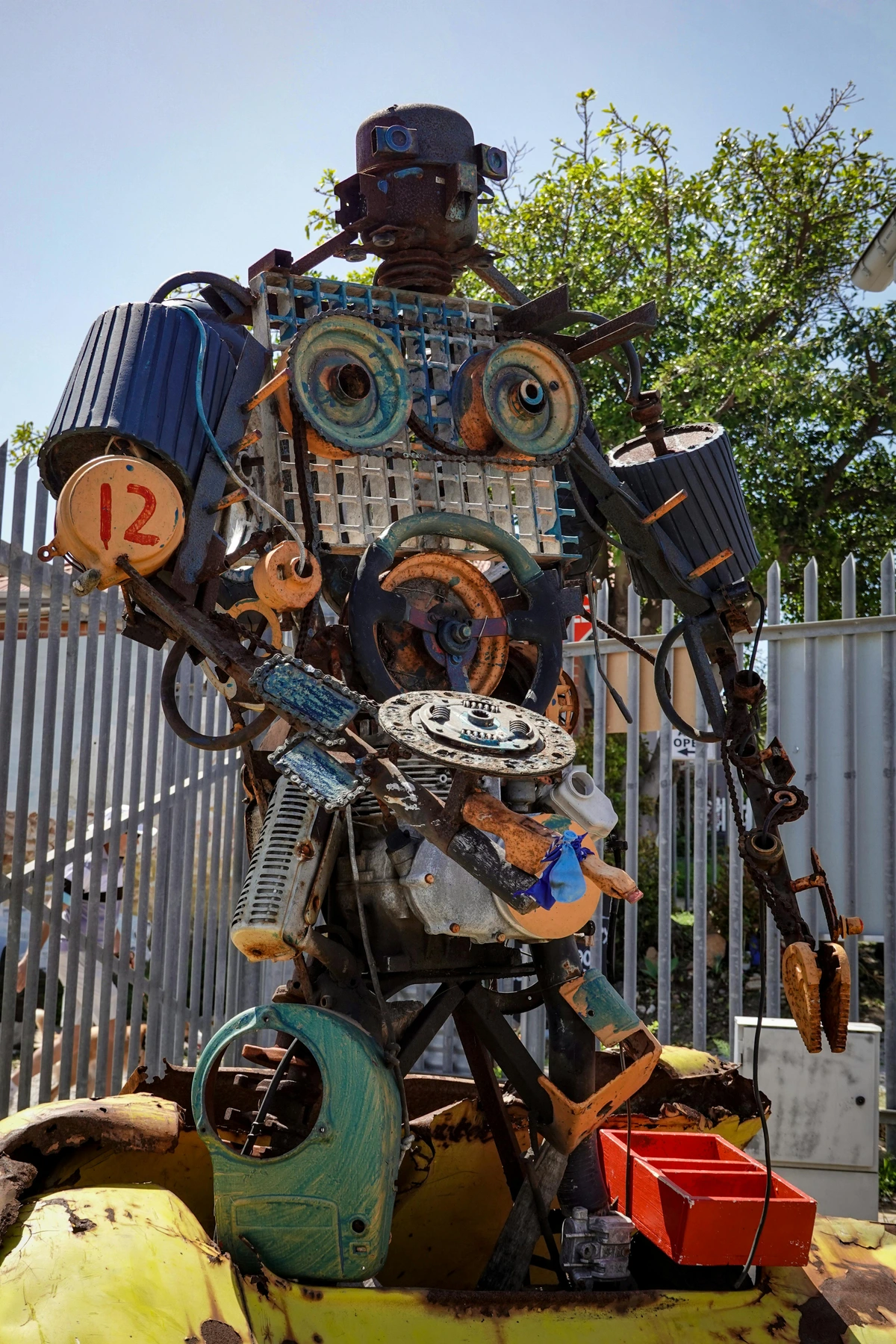

- Assemblage: A three-dimensional artwork created by combining found objects (e.g., Nevelson's sculptures made of wooden scraps).

- Combine: Similar to assemblage but often incorporates painting or other traditional media, blurring the lines between painting and sculpture (e.g., Rauschenberg's works featuring stuffed animals or tires).

- Junk Art / Trash Art: Broader terms often used to describe art made from discarded materials, frequently overlapping with Assemblage and Found Object art, but sometimes emphasizing the sheer volume or nature of the waste material itself.

Why Do Artists Choose the Discarded? It's More Than Just Being Cheap!

But why? Why trade the fresh canvas for rusty metal? Is it just because they're cheap? (Okay, sometimes, let's be real, that helps!). But there are definitely deeper reasons. It's a whole mindset, really. It's about seeing the world as a vast, open-air art supply store, full of unexpected treasures. Here are some of the driving forces behind the use of found objects:

- Challenging the Status Quo: Using everyday objects, especially mass-produced ones, was a direct challenge to the idea that art had to be unique, precious, and made by the artist's hand in a traditional way. It democratized art materials and questioned the very definition of artistic skill. Instead of showcasing the artist's mastery over paint or clay, found object art often highlights the artist's eye – their ability to see potential and meaning in the overlooked. For me, this is about breaking free from expectations, showing that creativity isn't limited by materials or tradition. It's a reminder that the idea can be just as powerful, if not more so, than the execution. I remember feeling a sense of liberation the first time I incorporated something non-traditional into my work; it felt like I was finally making my kind of art.

- Adding History and Narrative: Every found object has a past. It's been used, maybe broken, discarded. It carries the weight of its previous life, its function, its journey. When an artist incorporates it, they're bringing that history into the artwork, adding layers of meaning that fresh materials just don't have. It's like adopting a rescue dog versus buying a puppy – the rescue comes with a story, scars and all. I often wonder about the hands that touched an object before it came to me, the places it's been. Did that rusty key open a grand door or a forgotten box? That mystery is part of the art, a silent narrative waiting to be discovered. Found objects can carry not just physical history but also emotional or psychological weight, imbued with the energy of their past interactions. And sometimes, the sensory history is just as potent – the smell of old wood, the cool feel of worn metal, the sound of glass shards clinking. These sensations add another dimension to the object's story.

- Commentary on Society: Found objects, particularly discarded ones, can be powerful symbols of consumerism, waste, poverty, or industrialization. Artists use them to make statements about the world we live in, often highlighting issues we'd rather ignore. It's a way of holding up a mirror, made of trash. It forces us to confront things we might otherwise turn away from. Think about the sheer volume of plastic waste or electronic junk we generate – artists transforming these materials make us see that reality in a visceral way.

- Transformation and Rebirth: There's a magic in seeing something old and useless transformed into something new and meaningful. It's a kind of artistic alchemy, giving the object a second life and a completely different context. It's about seeing potential where others see only an ending. This resonates deeply with me; it's the core of the creative act, turning nothing into something. It's a hopeful message embedded in the discarded, a testament to resilience and reinvention.

- Accessibility and Relatability: We all recognize a broken bicycle wheel or a teacup. Using these familiar objects can make the art feel more accessible and relatable to viewers who might be intimidated by traditional forms. It bridges the gap between the gallery and everyday life. It's a way of saying, "Art is everywhere, for everyone." It invites the viewer to connect with the art through their own experiences with similar objects, making the encounter more personal.

- Pure Visual Interest: Sometimes, honestly, it's simply about the form, texture, color, or shape of the object itself. An artist might be drawn to the curve of a piece of driftwood or the patina of aged metal purely for its aesthetic qualities. It just looks cool. I've definitely picked things up just because the rust pattern was amazing, or the way light hit a broken piece of glass. The inherent beauty of the object is enough, a ready-made aesthetic waiting to be framed.

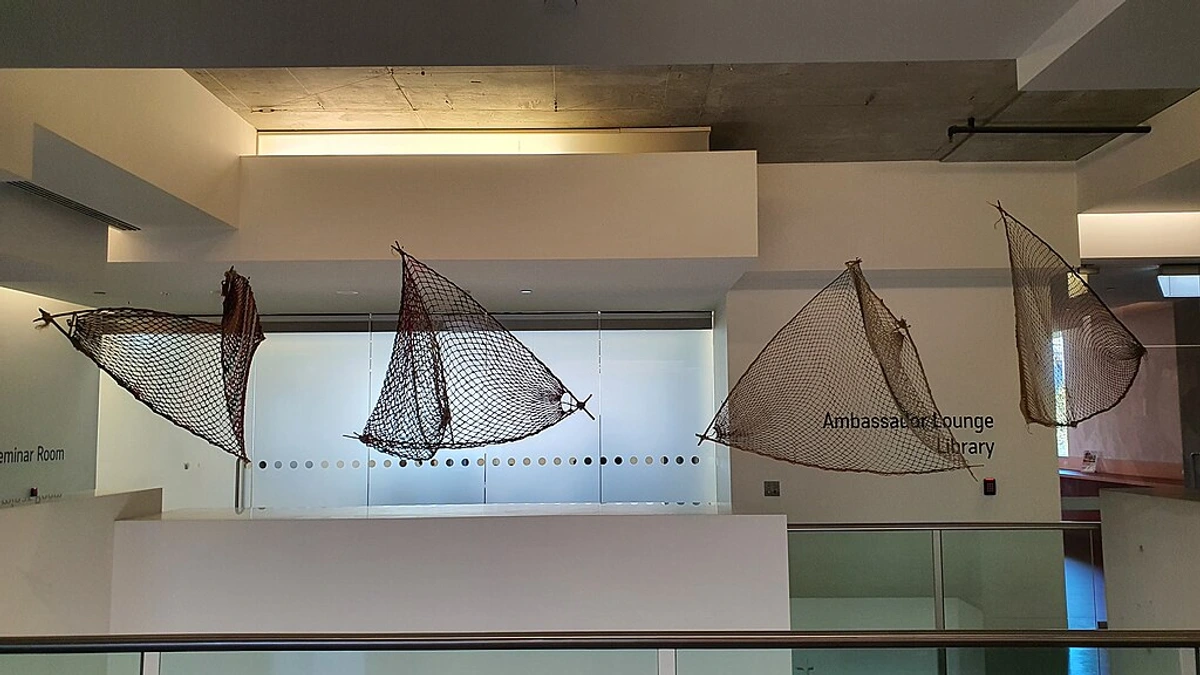

- Environmental Statement: In today's world, using discarded materials also carries a strong message about waste and sustainability. Artists can highlight environmental issues by transforming trash into treasure, encouraging viewers to think about consumption and recycling. It's art with a conscience, a way to make a point without shouting. Using materials like plastic bottles, e-waste, or discarded fishing nets directly confronts the environmental crisis we face, turning waste into a powerful visual argument. It's a way for art to participate in the urgent conversations of our time, sometimes even inspiring the use of eco-friendly art materials in other practices.

- Embracing Spontaneity and Serendipity: Unlike ordering specific materials from a supply store, working with found objects introduces an element of chance and surprise. The artist doesn't always know what they'll find, and the discovery of a particular object can completely change the direction of a piece or spark an entirely new idea. This unpredictability can be incredibly freeing and lead to unexpected creative breakthroughs. It's like the universe collaborating with you, offering up unexpected gifts. You have to be open to the happy accidents. The element of chance isn't just in the finding; it's also in the making. How will that rusty bolt react with that specific adhesive? Will that piece of wood split when I try to bend it? Embracing these unpredictable outcomes is part of the creative dance.

- Resourcefulness and Ingenuity: Figuring out how to incorporate a rusty bolt, a piece of broken ceramic, or a tangled fishing net into a stable, cohesive artwork requires significant problem-solving skills. Artists using found objects often become masters of unconventional joinery, adhesives, and structural support. There's a deep satisfaction in the technical challenge of making disparate materials work together. I've spent hours trying to figure out how to attach one weird thing to another, and the moment it finally clicks is incredibly rewarding. It's a puzzle where the pieces aren't designed to fit, and you have to invent the solution.

- The Element of Play: Let's not forget the simple joy of it! Working with found objects can feel like being a kid again, building something amazing out of whatever you find in the backyard or the junk pile. It encourages experimentation, improvisation, and a less precious approach to art-making. It's a playful dialogue between the artist and the object, a sense of discovery and fun that can be incredibly refreshing.

The Process: Seeing Potential Everywhere (Even in the Gutter)

So, how does an artist actually do this? It often starts with looking. Really looking. Not just at the obvious, but at the overlooked, the discarded, the things we walk past every day. It's a form of active observation, a treasure hunt in the everyday. It requires a certain kind of openness, a willingness to see beyond an object's intended purpose. It's about embracing serendipity – the happy accident of finding just the right piece at the right time. Sometimes the object finds you. The process isn't always linear; finding might inspire an idea, or an idea might send you searching for specific materials. It's a constant dance between intention and chance.

Here are some key steps, though they often overlap and loop back:

- Finding: This could be scavenging junk yards, flea markets, sidewalks, or even just rummaging through their own accumulated stuff. It's about being open to possibility and recognizing something interesting when you see it. It can be messy, dusty work, and you definitely get some strange looks! I've learned to carry gloves and a bag, just in case. I once found a beautiful, broken ceramic tile on a walk and carried it home like it was gold, much to the amusement of my partner. The thrill of the find is a huge part of it. It's about the sensory experience too – the smell of damp wood, the feel of cold metal, the glint of glass in the sun.

- Selecting: Not everything makes the cut. The artist chooses objects based on their form, texture, color, history, or the feeling they evoke. It's an intuitive process, a dialogue between the artist's vision and the object's inherent qualities. It's like building a visual vocabulary, piece by piece. Sometimes an object just feels right, even if you don't know exactly why yet. It speaks to you in some way.

- Transforming (or Not): This is where it varies wildly. Duchamp did very little, focusing on the conceptual shift (the Readymade). Nevelson painted everything black or white to unify disparate forms (Assemblage). Rauschenberg combined them with paint and other media (Combines, a form of ready-made aided art). Some artists might alter, cut, bend, or combine objects extensively – this is sometimes called "ready-made aided" art, where the found object is a starting point for significant modification. Techniques can include deconstruction, repetition, casting the object in a new material, or even using digital processes to manipulate its image or form. Others might simply present the object as is, letting its original state speak volumes. It's about deciding how much of the object's original identity to keep or discard, or how to merge it with new materials.

- Assembling/Composing: This step involves arranging and joining the selected objects. This could result in a collage (flat arrangement), an assemblage (three-dimensional construction), or a large-scale installation that fills a space. It requires technical skill to make the pieces hold together, and an artistic eye for composition and balance. Joining disparate materials like metal, wood, plastic, and fabric can be a real puzzle, requiring specific adhesives, fasteners, welding, or even custom-built supports to ensure structural integrity. The way objects are placed next to each other – creating tension, harmony, or unexpected relationships – is key to the final meaning.

- Presenting: How the object is displayed is crucial. A single object on a pedestal in a gallery feels very different from the same object left on the street. The context matters immensely, guiding the viewer's interpretation. This is also where practical challenges come in – not just conservation (how do you preserve something inherently fragile or prone to decay?), but also storage (where do you keep all this stuff?) and handling (is that rusty metal safe?). It often requires creative solutions and a lot of problem-solving. I've had to get really creative with storage over the years; my studio often looks like a carefully organized hoard! And my partner has learned to just sigh when I come home with another bag of 'treasures'.

- Titling: The title given to a found object artwork can dramatically shift its meaning. A simple object like a bicycle wheel can become profound or humorous depending on the words attached to it, guiding the viewer's interpretation and adding another layer to the conversation between the artist, the object, and the audience. A title can unlock a hidden narrative or add a layer of irony.

It's a process that requires curiosity, patience, and a willingness to experiment. It reminds me a bit of how I approach a blank canvas – sometimes the first mark is the hardest, but once you start, the possibilities unfold. It's about embracing the journey, even if it involves digging through literal junk. I've certainly had my share of dusty hands and strange looks while hunting for materials! These steps might sound simple, but artists throughout history have approached them in wildly different ways, leading to groundbreaking work.

Beyond the Object: Scale, Context, and Ephemerality

Found object art isn't just about the object itself; it's deeply intertwined with its presentation and sometimes, its temporary nature. The scale can range dramatically, influencing how we experience the work and the message it conveys:

- Intimate and Personal: Small-scale works, like Joseph Cornell's shadow boxes filled with collected ephemera, create miniature worlds that invite close inspection and contemplation. These often feel like personal archives or dreamscapes, drawing the viewer into a private narrative.

- Large-Scale Installations: Artists frequently use found objects to create massive, immersive environments or sculptures that fill entire rooms or public spaces. Think of installations made from thousands of discarded items, overwhelming the viewer with the sheer volume of waste or material. These works often make powerful social or environmental statements, using scale to amplify their message. Rudolf Stingel, known for his large-scale installations, sometimes incorporates found elements or materials that evoke a sense of history or place.

- Site-Specific Works: Sometimes, the location where the objects are found or where the artwork is displayed is integral to the piece. Artists might create temporary installations using materials found on a specific beach or in a particular abandoned building, commenting directly on that place's history or environmental state. These works often embrace the ephemeral, designed to exist only for a limited time before being dismantled or left to decay naturally, adding a layer of meaning about impermanence.

This flexibility in scale means found object art can engage viewers in vastly different ways, from quiet, personal reflection to confronting overwhelming societal issues. Furthermore, some artists deliberately choose materials that will degrade over time, making the artwork itself a commentary on impermanence, the cycle of life and death, or the transient nature of consumer culture. This adds another layer of conceptual depth, challenging traditional notions of art as something meant to last forever. Found objects can also be incorporated into performance art, used as props or integral elements in live actions, adding their history and materiality to the ephemeral nature of the performance itself. They can even appear in photography, either as subjects, props, or physically incorporated into the photographic print or object itself.

Key Artists Who Mastered the Found Object

Building on those initial rebellious ideas, this practice has a rich history, and several artists are absolute legends in the field. They didn't just use found objects; they fundamentally changed how we think about art because of them. Learning about their work was incredibly influential for me, opening my eyes to the possibilities beyond traditional materials. You might have heard of some of them:

Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968)

The guy who arguably started it all with his Readymades. Readymades are a specific type of found object art, often mass-produced items, that Duchamp selected and presented as art with minimal or no alteration, shifting the focus from craftsmanship to the artist's conceptual choice. He took mass-produced, everyday objects, signed them, and presented them as art. His most famous (or infamous) is Fountain (1917), a porcelain urinal signed "R. Mutt." Talk about challenging the system! He wasn't transforming the object; he was transforming its context and our perception of it. It was a philosophical act as much as an artistic one, questioning authorship, originality, and the very definition of what art is. It certainly made the art world furious, which I imagine he found quite amusing. Learning about Duchamp's audacity was a pivotal moment for me, freeing my own mind from rigid ideas about what materials were 'allowed' in art. It showed me that the idea could be the art. Fountain, despite its humble origins as a piece of plumbing, became a symbol of artistic freedom and the power of the artist's choice.

Kurt Schwitters (1887-1948)

A German artist associated with Dada, Schwitters developed his concept of Merz, which involved creating collages and assemblages from found materials like bus tickets, newspaper scraps, and packaging. His Merzbau was a massive, evolving architectural construction built within his own home from collected junk. It's a fantastic example of how found objects could be used to create immersive, personal worlds, turning his entire life and its detritus into a single, ongoing artwork. His work often feels like a chaotic, beautiful diary made of trash. Seeing images of his Merzbau made me think about how our own accumulated objects tell the story of our lives, a kind of unintentional self-portrait. His collages, like Merz Picture 25 A. The Star Picture (1920), are intricate tapestries of discarded paper, each fragment carrying a whisper of its former life.

Robert Rauschenberg (1925-2008)

Known for his Combines, which blurred the lines between painting and sculpture by incorporating found objects and everyday items onto or into his canvases. Think stuffed animals, tires, furniture. A famous example is Monogram (1955-59), which features a stuffed angora goat with a tire around its middle, standing on a painted platform. It's like a chaotic, beautiful collision of the world onto a flat surface. His work is a fantastic example of mixed media art, showing how found objects can coexist and interact with traditional art materials. Rauschenberg's fearless mixing of materials always felt incredibly liberating to me; it felt like permission to use anything. Monogram is a prime example of this fearless approach, combining painting, collage, and sculpture in one audacious piece.

Louise Nevelson (1899-1988)

She collected discarded wooden objects – chair legs, crates, architectural fragments, balusters – and assembled them into large, often monochromatic (usually black, white, or gold), sculptural walls or environments. Painting the disparate objects a single color helped to unify them, focusing the viewer on the forms, shadows, and overall structure rather than the individual items' original identities. Her work is incredibly powerful, turning forgotten scraps into monumental, almost architectural, pieces. Think of her Sky Cathedral series, where countless wooden pieces are arranged into towering, complex structures. Her approach is a prime example of assemblage art on a grand scale. Nevelson's ability to find harmony in chaos through the simple act of painting everything one color is something I deeply admire; it's a powerful act of transformation. Sky Cathedral (1958) is a breathtaking example of how she transformed discarded wood into a majestic, unified environment.

Arte Povera

Emerging in Italy in the late 1960s, the Arte Povera (literally "poor art") movement also heavily utilized found, everyday, and often humble materials like soil, rags, wood, and industrial waste. Artists like Michelangelo Pistoletto and Jannis Kounellis used these materials to challenge the commercialization of art and critique consumer culture, creating works that were often ephemeral or site-specific. Their focus on the raw, intrinsic qualities of these 'poor' materials offered a different perspective from the Dada/Surrealist approach, rooted more in political and social commentary and a connection to nature and history. It was a powerful statement against the slickness of the burgeoning art market, a return to basics with a political edge. Pistoletto's Venus of the Rags (1967), a classical sculpture facing a pile of discarded clothes, is an iconic example of this movement's juxtaposition of high art and humble materials.

Contemporary Artists

Many contemporary artists continue this tradition, often with new twists and addressing modern concerns. Artists like Ai Weiwei use found objects, sometimes on a massive scale (like antique wooden stools or bicycles), to comment on history, culture, and politics, often referencing specific Chinese contexts. Consider the work of El Anatsui, who creates shimmering, large-scale sculptures from discarded bottle caps and other metal waste, transforming materials of consumption into breathtaking tapestries that speak to history, trade, and the environment. His work is a stunning example of turning literal trash into transcendent beauty. Betye Saar is another incredible artist who uses found objects, particularly those with racist imagery or personal significance (like Aunt Jemima figures or washboards), to create powerful assemblages that explore African American history, spirituality, and identity, reclaiming narratives through discarded items. Subodh Gupta, an Indian artist, uses everyday objects like stainless steel tiffin boxes and utensils to create large-scale sculptures and installations that comment on Indian society, consumerism, and globalization, turning symbols of daily life into monumental forms. Other artists might use electronic waste, plastic debris from the ocean, or materials specific to their local environment, keeping the practice relevant and ever-evolving, constantly responding to the modern world. Found objects also feature prominently in contemporary street art and public installations, bringing art directly to the people and engaging with urban environments.

These artists, from the pioneers to today's innovators, demonstrate the enduring power and versatility of the found object as a medium for expression, critique, and transformation.

Challenges of Working with Found Objects (It's Not Always Glamorous!)

While the freedom and narrative potential of found objects are immense, this medium isn't without its difficulties. It's not as simple as just picking something up and calling it art (though Duchamp might argue it can be!). Artists working with these materials often face unique challenges:

- Sourcing and Availability: Finding the right objects can be a time-consuming and unpredictable process. You can't just order a specific shade of rust or a perfectly broken teacup from an art supply store. It requires constant searching, patience, and often, a bit of luck. My own studio often looks like a carefully curated junk shop because I never know when that perfect piece will turn up. Explaining your growing collection of 'treasures' to friends or family can also be... interesting. "No, really, this pile of old bottle caps is for my art!" I once spent weeks hunting for just the right kind of weathered wooden plank for a piece, checking every skip and salvage yard I passed. It felt a bit obsessive, but the satisfaction when I finally found it was immense. And yes, my partner has definitely learned to just sigh when I come home with another bag of 'treasures'.

- Conservation and Preservation: Unlike traditional art materials designed to last, found objects are often inherently fragile, prone to decay, rust, fading, or breaking down over time. Preserving these works for future generations requires specialized knowledge and techniques, which can be costly and complex. How do you conserve a sculpture made of old tires and driftwood? It's a real puzzle. It's also worth noting, as mentioned earlier, that some found object art is intentionally ephemeral, designed to decay or be temporary, adding another layer of meaning about impermanence or the cycle of life.

- Structural Integrity: Assembling disparate objects into a cohesive artwork can be technically challenging. How do you make sure a sculpture made of various found items is stable and won't fall apart? It requires ingenuity, engineering skills, and often, a lot of trial and error. Sometimes, the object dictates the structure, and you have to work with its inherent form and limitations. I've definitely had pieces collapse on me mid-assembly, leading to a mix of frustration and unexpected new possibilities. Once, I spent hours carefully balancing a stack of old ceramic shards, only for the whole thing to spectacularly tumble down just as I was about to apply the final adhesive. It was frustrating, but the way the pieces broke differently actually sparked an idea for a new composition. It's a constant battle against gravity and the inherent nature of the materials.

- Ethical Considerations: While I touched on this in the FAQ, it's a significant challenge. Artists must be mindful of where they source objects. Taking items from private property, historical sites, or places where they might still be needed or hold cultural significance is unethical. Focusing on truly discarded materials or purchasing from legitimate sources like flea markets is crucial. It's about finding what's been let go, not taking what's still held onto. Always be mindful of local regulations and property rights.

- Storage and Handling: Found objects can be bulky, dirty, and require significant space to store before they are used. Handling potentially sharp, rusty, or contaminated materials also poses risks. It's definitely not always a glamorous process! You might need a tetanus shot and a good dust mask. But the potential reward of finding that perfect piece makes it worthwhile.

- Valuation and Market Acceptance: This is a big one. How do you price a piece of art made from trash? The value isn't in the materials themselves, but in the concept, the artist's reputation, and the execution. This can be confusing for collectors and challenging for artists to navigate the art market. Convincing someone that a discarded item is worth investing in requires a shift in perspective, which is part of the art's power, but also a practical hurdle. It challenges traditional notions of value based on expensive materials or labor, focusing instead on the idea and the artist's unique perspective. It's a fascinating part of the art market to explore.

These challenges add another layer to the artist's practice, making the successful creation of found object art even more impressive. Despite these hurdles, the power of the discarded object continues to inspire.

Appreciating Found Object Art: How to See the Magic

Okay, so how do you even start looking at this stuff? If you're new to this kind of art, it might feel a bit... weird. And that's okay! It's meant to make you think. It challenges your assumptions. It invites you into a different way of seeing. Here are a few ways to connect with it and maybe even start to love it:

- Look Beyond the Material: Don't just see a rusty bike wheel. Ask yourself why the artist chose that specific bike wheel. What does its rust, its shape, its history make you feel? What stories does it suggest? What was its life before it became art? When I look at a piece, I try to imagine its journey. What memories are embedded in that worn surface? For example, if you see an artwork incorporating old, worn-out shoes, don't just see footwear. Think about the miles walked, the lives lived, the journeys taken in those shoes. What stories could they tell? What does the artist want you to feel about those journeys?

- Consider the Context: Where is the art displayed? Is it in a pristine gallery, a public space, or somewhere unexpected? What is it called? What do you know about the artist's background or intentions? All of this adds layers of meaning. The setting can completely change how you perceive the object. A discarded shoe in a gutter is just trash; the same shoe on a pedestal in a museum, titled

Journey's End, becomes something else entirely. How does the title or location influence your reading? - Think About Transformation: If the object has been altered or combined, how has its original meaning changed? What new meaning has been created through its juxtaposition with other objects or materials? It's like a visual riddle, a puzzle the artist invites you to solve. How does putting a teacup next to a broken clock change how you see both? Using the shoe example, if it's combined with a map or a compass, the theme of journey becomes explicit. If it's filled with soil and a sprouting seed, it speaks of rebirth and nature reclaiming the discarded. What unexpected connections does the artist create?

- Embrace the Questions: Found object art often raises questions about value, authorship, and the definition of what art is itself. It's okay not to have all the answers. The questioning is part of the experience. It's an invitation to dialogue, a chance to challenge your own perspectives. It's a conversation between you, the artist, and the object. What questions does the artwork spark in you?

It's a different way of seeing, and like learning to read a painting, it gets easier and more rewarding with practice. You might even start seeing potential art everywhere you look! Maybe even in your own junk drawer. What hidden treasures are waiting to be discovered? It's about opening your eyes to the stories and possibilities hidden in plain sight. Look for it in unexpected places – a local community center, a small independent gallery, or even finding art in unexpected places like cafes or boutiques. You might be surprised by what you find.

FAQ: Burning Questions About Found Object Art

Q: Is found object art really art?

A: Ah, the million-dollar question! This is exactly what artists like Duchamp wanted us to ask. Most art critics and historians agree that yes, it absolutely is. Art is less about the materials used and more about the concept, the intention, and the statement the artist is making. Found objects are just another medium, albeit a provocative one. It forces us to reconsider our definitions of what art is. If it makes you think, feel, or question, isn't that art doing its job?

Q: Where can I see found object art?

A: You can find it in major museums focusing on modern and contemporary art, like the MoMA in New York or the Tate Modern in London. Many contemporary art galleries also feature artists who work with found objects. Keep an eye out in contemporary art galleries in Europe or the US! You might even stumble upon it in unexpected places like cafes or public spaces. Don't forget smaller, local galleries – they often showcase innovative artists using diverse materials. Sometimes, the most interesting pieces are found outside traditional venues! You might even find it in a museum in Den Bosch if you're in the Netherlands.

Q: Can I make my own art with found objects?

A: Absolutely! It's a fantastic way to get creative and see the world differently. Start small. Collect interesting items you find, think about how they relate to each other, and experiment with arranging or combining them. There are no rules, just your imagination. It's a very accessible way to start making mixed media art or assemblage art. Just be warned, you might start accumulating a lot of 'interesting' junk! My studio is definitely a testament to this.

Q: How do artists find inspiration from found objects?

A: Inspiration can strike in many ways! Sometimes, the object itself sparks an idea – its shape might suggest a figure, its texture might evoke a feeling, or its history might hint at a narrative. Other times, an artist might have a concept in mind and actively search for objects that fit that vision. The element of chance is also a huge source of inspiration; finding an unexpected object can completely change the direction of a piece or lead to entirely new creative paths. It's a dynamic process of observation, intuition, and playful experimentation.

Q: Can I buy found object art, and how is it valued?

A: Yes, you absolutely can buy found object art! You'll find it in galleries specializing in contemporary art, at art fairs, and sometimes directly from artists. How it's valued is complex and often depends less on the intrinsic value of the materials (a rusty nail isn't worth much on its own) and more on the artist's reputation, the concept behind the work, its historical significance, and market demand. It challenges traditional notions of value based on expensive materials or labor-intensive craftsmanship, focusing instead on the idea and the artist's unique perspective. It's a fascinating part of the art market to explore. Don't expect a piece made of trash to be cheap just because of the materials; you're paying for the idea and the artist's unique perspective. You can explore options to buy art online or in galleries, including pieces that incorporate found objects.

Q: Are there any ethical considerations when collecting found objects?

A: Yes, definitely. While scavenging can be part of the process, it's crucial to be respectful. Don't trespass on private property, disturb historical sites, or take things that are clearly someone else's or have cultural significance. Focus on public spaces where discarding is common, or look in places like flea markets and junk shops where items are intended for sale or disposal. It's about finding discarded items, not taking things that are still valued or needed by others. Always be mindful of local regulations and property rights. When in doubt, leave it or ask permission.

Q: What's the difference between found object art and recycling/upcycling?

A: This is a great question! While there's overlap, the key difference lies in intent and context. Recycling breaks down materials to create something new (e.g., melting plastic bottles into pellets). Upcycling transforms discarded items into something of higher value or quality, often functional (e.g., turning old pallets into furniture). Found object art, however, is primarily concerned with the conceptual or aesthetic statement made by presenting the object as art, often retaining its original form and history. The focus is on meaning, critique, or visual impact within an art context, rather than utility or material transformation for reuse. An artist might use upcycled materials within a found object artwork, but the core practice is about the object's journey into the art world.

Q: Is it okay to modify found objects extensively?

A: Absolutely! While Duchamp's Readymades emphasized minimal alteration, many artists extensively modify found objects through cutting, painting, combining, or other processes. This is often referred to as "ready-made aided" art or simply assemblage. The degree of modification depends entirely on the artist's intention and the statement they want to make. The transformation itself can be a powerful part of the artwork's meaning.

Q: Are there legal issues with using found objects?

A: Generally, using objects found in public trash or purchased from junk shops is fine. However, legal issues can arise if you take objects from private property without permission, from protected historical or archaeological sites, or if the object itself is subject to copyright or intellectual property laws (though this is less common with simple discarded items). It's always best to stick to clearly discarded materials in public areas or purchase items from legitimate sources to avoid potential problems.

Q: How are found objects used in other art forms like photography or film?

A: Found objects can appear in photography as subjects, props, or even physically incorporated into the print itself (like collages or mixed media). In film and video, they can be used as symbolic props, set dressing, or even as the basis for stop-motion animation or experimental film techniques using found footage or objects. Their inherent history and texture add layers of meaning to these visual mediums.

Conclusion: A New Way of Seeing

Artists who use found objects invite us to look at the world with fresh eyes. They show us that beauty, history, and meaning aren't just found in traditional materials or pristine conditions, but can be unearthed in the everyday, the discarded, the overlooked. It's a powerful reminder that creativity is about perception and transformation, turning the ordinary into the extraordinary.

So, the next time you see a piece of 'junk', remember the artists who saw a masterpiece. It might just change how you see the world, one found object at a time. And who knows, maybe it will inspire you to start your own collection or create something new. The world is full of potential, just waiting to be found. It's a philosophy that extends beyond the studio, influencing how we see value and possibility everywhere, perhaps even in the art we choose to bring into our own lives, whether it's a found object piece or something you discover and buy because it speaks to you. It's all about connection and seeing the world through a unique lens, a journey of discovery that might even lead you to explore a museum in Den Bosch or reflect on your own timeline of creative discovery.