Art About Natural Disasters: Meaning, Resilience & Climate Crisis

Explore how artists capture the raw power and emotion of natural disasters across history and mediums, from documentation and processing trauma to addressing the climate crisis. Discover art's role in finding meaning, fostering resilience, and preserving cultural memory in the storm. Includes famous examples and where to find disaster art.

Art About Natural Disasters: Finding Meaning and Resilience in the Storm

Okay, let's be honest. Natural disasters? Not exactly a light and breezy topic for a Sunday afternoon chat, is it? My mind usually drifts to color palettes, the perfect brushstroke, or maybe whether I've left the studio door unlocked again. But then something happens – a hurricane on the news, a distant earthquake tremor, even just a truly spectacular thunderstorm – and you're reminded, quite forcefully, of the sheer, untamed power of the natural world. As an artist, I often explore the raw energy of the world around us, translating that immense, chaotic force into forms I can understand, or at least grapple with, through abstract shapes and vibrant colors. This article is my attempt to make sense of how art helps us navigate these turbulent times, exploring the topic through my own personal lens, much like trying to paint the sound of that massive hailstorm that once rattled my studio windows – impossible, but the attempt itself is a way of processing the experience.

It's humbling. Terrifying. And, if we're being completely honest, sometimes even strangely beautiful in its raw, destructive energy. As an artist, or just as a human trying to make sense of things, you can't help but feel something profound when faced with forces so much larger than yourself. And where do we humans often turn when we're grappling with the big, messy, overwhelming stuff? Art, of course.

Art about natural disasters isn't new. It's a thread woven through the history of art, a consistent response to moments when the earth shakes, the waters rise, or the winds rage. This article explores why artists feel compelled to depict such events, how they capture the unimaginable across different mediums and styles, and the impact and meaning found in such powerful work. It's artists trying to capture the unimaginable, process the trauma, or simply stand in awe of the sublime terror of nature unleashed.

Why Do Artists Turn Towards the Chaos?

Why would anyone choose to depict such devastation? It seems counterintuitive, right? Wouldn't we rather paint sunny meadows or cheerful portraits? But artists are often drawn to the edges of human experience, the moments that challenge us, break us, and force us to confront reality in its most raw form. It's a way to process the overwhelming, to find a language for the unspeakable, and sometimes, even to find glimmers of resilience and hope amidst the ruin.

I think there are a few key reasons artists feel compelled to tackle natural disasters. For me, it often comes back to that feeling of being overwhelmed, that need to translate something immense and chaotic into a form I can understand, or at least grapple with. It's like trying to paint the sound of that hailstorm – impossible, but the attempt itself is a way of processing the experience.

- Documentation: Sometimes, it's about bearing witness. Before photography and video, painting was one of the primary ways to record events, including catastrophes. These works served as news, warnings, and historical records. Think of detailed engravings or paintings depicting events like the Great Fire of London (1666) or the Lisbon earthquake of 1755 – they weren't just art; they were visual history, showing the scale of destruction to a wider audience. Consider also works like The Great Flood by Joseph Mallord William Turner, which captures the terrifying scale of a biblical deluge, or historical prints documenting specific storms or volcanic eruptions, serving as crucial visual records for those far away. With the rise of photography in the 19th century, the role of painting shifted somewhat from primary documentation to more interpretive, emotional, or symbolic responses.

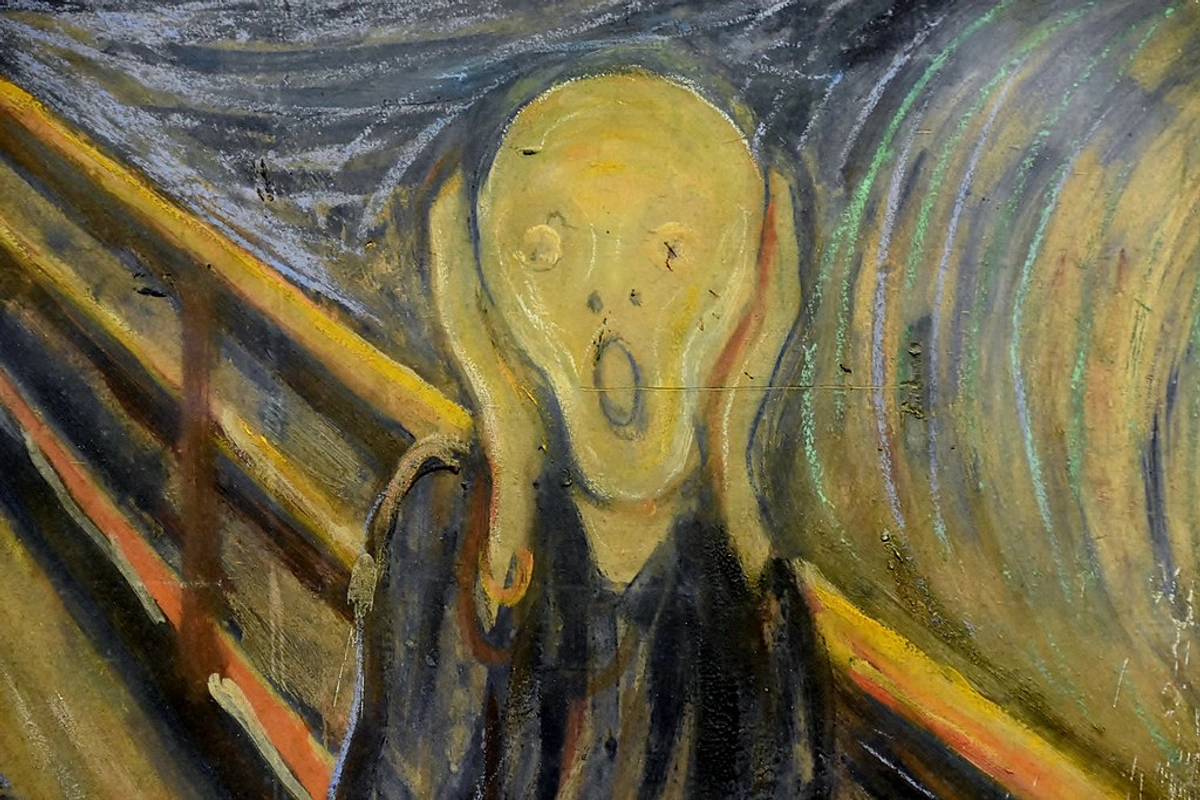

- Emotional Processing: Disasters are traumatic. Art provides a vital outlet for expressing the fear, grief, loss, and confusion that follow. It's a way to externalize overwhelming internal states. This often leads to dramatic art styles or movements like Expressionism, where feeling takes precedence over realism. While Edvard Munch's "The Scream" captures a universal feeling of existential dread that resonates with disaster's fear, consider artworks created directly in the aftermath, like Francisco Goya's The Disasters of War series, which, though depicting the horrors of human conflict, powerfully conveys the raw suffering and trauma that also follows natural catastrophes. For a more direct response to nature's fury, look at works created after specific events, like paintings or drawings made by survivors or artists witnessing the destruction, attempting to grapple with the sheer scale of loss. For me, the very act of putting paint on canvas, of wrestling with color and form, can be a way to work through difficult emotions, even if the subject isn't explicitly traumatic. Using turbulent textures (like impasto) or a specific color palette of stormy grays, deep blues, or fiery reds can directly convey the feeling of chaos and pain.

- Social Commentary: Art can highlight the human cost, critique inadequate responses, or call for aid and change. It can be a form of protest art, demanding that viewers pay attention to inequality or systemic failures exposed by a disaster. Think of photographs documenting the disproportionate impact of Hurricane Katrina on marginalized communities, or murals painted in disaster-stricken areas that serve as both memorials and calls for political action or aid. For example, the work of photographer Robert Polidori documented the devastation and social inequalities laid bare by Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans, offering a powerful visual critique. Community murals in places like Haiti after the 2010 earthquake or in areas affected by wildfires in California serve as powerful visual testaments to both suffering and collective calls for support and systemic change.

- Awe and the Sublime: There's a long tradition in art of depicting the sublime – that feeling of awe mixed with terror when confronted with something vast and powerful, like a raging storm or a towering wave. Philosophers like Edmund Burke and Immanuel Kant explored this concept, describing it as an experience that overwhelms our senses and reason, yet elevates the mind by reminding us of our capacity to contemplate such immensity. In disaster art, the sublime reminds us of our smallness and vulnerability in the face of nature's raw power, but also our ability to perceive and represent it. Artists evoke the sublime through techniques like dramatic scale (dwarfing human figures), intense contrasts of light and shadow (chiaroscuro), turbulent brushwork, and overwhelming compositions. For me, as an artist, trying to capture that feeling – the terrifying beauty of a storm, the overwhelming scale of a mountain – is a way to connect with something much larger than myself, to translate that raw energy onto the canvas. It's not about replicating reality, but about evoking that feeling of being dwarfed by something magnificent and terrifying. Thomas Cole's Romantic landscapes, for instance, often evoke this feeling, hinting at forces beyond human control, much like the hailstorm that made me feel so small in my studio.

Thomas Cole's work often captures the sublime, hinting at forces beyond human control.

Thomas Cole's work often captures the sublime, hinting at forces beyond human control. - Allegory and Metaphor: Sometimes, a natural disaster in art isn't just about the event itself. It can serve as a powerful metaphor for human conflict, societal upheaval, personal loss, or the fragility of existence. Artists use the visual language of destruction and chaos to speak to deeper, often uncomfortable, truths about the human condition. A flood might symbolize overwhelming grief, a crumbling building the collapse of social structures, or a raging fire the destructive nature of anger or conflict. This adds layers of meaning, allowing the artwork to resonate beyond the specific event it depicts.

So, artists turn towards chaos not because they enjoy devastation, but because it's a profound human experience that demands a response – whether to document, process, critique, stand in awe, or explore deeper metaphorical truths. And how do they manage to capture something so immense and overwhelming?

Capturing the Unimaginable: Styles, Approaches, and Famous Examples

How do you even begin to paint a hurricane or a volcanic eruption? Artists have used countless approaches, from meticulous realism to wild abstraction. Historically, you see a lot of detailed, often romanticized, depictions.

Think of shipwrecks or floods, designed to evoke strong emotions in the viewer. J.M.W. Turner, a master of the Romantic period, frequently depicted the raw power of the sea and storms, like in his painting The Slave Ship, where the turbulent ocean mirrors human cruelty. His works capture the sublime terror and beauty of nature unleashed. Volcanic eruptions have also been a recurring theme. Joseph Wright of Derby's paintings of Mount Vesuvius erupting, often seen at night, capture the terrifying beauty and destructive force of the volcano, tapping directly into the sublime. Other historical examples include depictions of the eruption of Mount Vesuvius burying Pompeii, captured in paintings and frescoes, or medieval manuscripts illustrating floods and famines.

Beyond Western traditions, many cultures have long histories of depicting natural phenomena and disasters. Japanese Ukiyo-e prints, for example, famously capture the power of waves (Hokusai's The Great Wave off Kanagawa is an iconic example, though often interpreted beyond just a disaster) or the majesty of Mount Fuji, a volcano. Dutch Golden Age seascapes, while often celebrating maritime power, also frequently depicted ships battling violent storms, reflecting the nation's vulnerability to the sea. In other cultures, like those in the Pacific Ring of Fire, art might depict volcanic eruptions or earthquakes through mythology, ritual objects, or narrative paintings, often emphasizing the power of nature spirits or the importance of community survival. Indigenous Australian art, for instance, includes depictions of floods and other environmental events, often tied to ancestral stories and the deep connection to the land.

The specific type of disaster – a sudden earthquake versus a slow-moving flood or a raging fire – can also heavily influence the artistic approach, dictating the sense of movement, color palette, and composition used. An earthquake might be depicted with jagged lines and fractured forms, a flood with sweeping, fluid brushstrokes, and a fire with intense, chaotic reds and oranges.

Artists also employ specific techniques to convey the power and chaos. Impasto, or thick application of paint, can create turbulent textures that mimic rough seas, swirling winds, or piles of rubble. It gives the surface a physical, almost violent energy – something I often strive for in my own work when trying to capture raw emotion or the feeling of dynamic movement. Dynamic composition, using diagonal lines, sharp angles, and swirling forms, can suggest movement, instability, and collapse, pulling the viewer into the disorienting experience of a disaster. The use of specific color palettes, from stormy grays and blues to fiery reds and oranges, directly impacts the emotional tone, evoking feelings of dread, danger, or even strange beauty. Think of the oppressive grays in depictions of the Dust Bowl or the fiery reds in paintings of volcanic eruptions.

Théodore Géricault's 'The Raft of the Medusa' is a powerful example. While the initial cause was human error, the painting vividly portrays the desperate struggle against the overwhelming, indifferent forces of the sea and storm, a struggle that mirrors the experience of natural disasters.

As art evolved, so did the ways of representing chaos. Abstract art can be incredibly effective at conveying the feeling of a disaster – the disorientation, the noise, the sheer force – without showing a literal scene. Think of swirling colors, jagged lines, and turbulent textures. It's less about what happened and more about how it felt. Abstract Expressionism, with its focus on conveying emotion through form and color, can often evoke the chaos and intensity of such events. For me, sometimes the most powerful way to express overwhelming emotion isn't through a literal image, but through the raw energy of color and form on the canvas. It's about capturing the essence of the feeling, not the visual details.

Sometimes, abstraction captures the feeling of chaos better than realism.

Symbolism also plays a huge role. A broken tree, a submerged house, a lone figure against a vast, angry sky – these images become potent symbols of loss, resilience, and vulnerability. Artists use these visual metaphors to speak to deeper truths about the human condition when faced with such events.

Beyond Painting: Other Forms of Disaster Art

It's not just paintings, of course. Natural disasters have inspired all sorts of types of artwork. Each medium offers a different way to process and present the experience, adding layers to the conversation and reaching different audiences. Exploring these diverse forms reveals the multifaceted ways artists respond to catastrophe.

- Photography: Perhaps the most immediate and visceral response. Documentary photography captures the raw reality of the event and its aftermath, providing crucial visual records and bearing witness to suffering and survival. Think of the iconic, heartbreaking images from events like the Dust Bowl (documented by Dorothea Lange), the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina (documented by Robert Polidori, among others), or the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami. Photography galleries, like The Photographers Gallery in London or the European House of Photography in Paris, often feature powerful documentary work that confronts viewers with the stark reality of such events.

Photography galleries often feature powerful documentary work.

Photography galleries often feature powerful documentary work. - Sculpture and Installation: Artists use debris, salvaged materials, or create new forms to reflect on destruction, loss, and rebuilding. Installations can recreate the feeling of being in a damaged space or use collected objects as memorials. Imagine a sculpture built from twisted metal and splintered wood found after a hurricane, transforming wreckage into poignant memorials. A notable example is the work of artists who have used materials salvaged from disaster zones, turning destruction into powerful symbols of recovery. For instance, artists working after the 2011 Japanese tsunami created installations and sculptures from debris, transforming remnants of destruction into poignant memorials and symbols of resilience. These works bring the physical reality of the disaster into the gallery space, forcing a tangible confrontation with the aftermath.

Sculpture and installation can use space and materials to evoke powerful feelings.

Sculpture and installation can use space and materials to evoke powerful feelings. - Performance Art: Can explore themes of survival, vulnerability, and the physical experience of being in a disaster or its aftermath. Artists might use their bodies to represent the struggle against the elements or the process of recovery. A performance piece might involve an artist enduring simulated wind and rain, or performing repetitive, exhausting tasks that mimic the labor of cleanup and rebuilding. Consider performance artists who have enacted rituals of mourning or resilience in public spaces affected by disasters, using their bodies to embody the collective experience and evoke empathy in viewers. For example, some performance artists have created pieces that involve physically navigating simulated disaster environments or performing acts of endurance that mirror the struggle for survival. These ephemeral works often emphasize the human body's fragility and strength.

- Textile Art: Can be used to create memorials, tell stories of survival, or even incorporate salvaged fabrics. Community quilt projects, for instance, have been used to process collective grief and preserve memories after disasters, incorporating scraps of clothing or household textiles from damaged homes into a collective artwork that represents shared loss and resilience. These textiles become powerful artifacts, literally woven with the history and emotions of the event. Artists like Ann Hamilton have created large-scale textile installations that evoke themes of collective memory and vulnerability, which resonate strongly with the aftermath of disasters. The tactile nature of textiles can offer a sense of comfort and connection.

- Digital Art, Video, and VR: Technology offers new ways to depict and experience disasters. Digital simulations can visualize the scale of events like rising sea levels or tsunamis. Video installations can immerse viewers in the sights and sounds of a storm or its aftermath. Virtual reality can even place viewers within a simulated disaster zone, creating a powerful, albeit potentially overwhelming, sense of presence and vulnerability. These mediums allow for dynamic, interactive, and often data-driven explorations of natural forces and their impact. For example, artists and designers have created VR experiences that simulate the impact of climate change on coastal cities or visualize the spread of wildfires, making abstract data feel terrifyingly real. They can also be used for educational purposes or to raise awareness on a global scale.

The Impact on the Viewer

Looking at art about natural disasters can be challenging. It can trigger empathy, fear, or even a sense of helplessness. It might make you flinch, turn away, or feel a knot in your stomach. But it can also foster understanding, build connection with those affected, and serve as a powerful reminder of the importance of preparedness and community. By seeing the human face of a disaster, even through artistic interpretation, viewers can feel a sense of shared humanity and be moved to offer support or reflect on their own circumstances. Art can also inspire concrete action, prompting donations, volunteer efforts, or engagement with policy discussions related to disaster relief and climate change.

It makes you think about your own vulnerability, doesn't it? I mean, I worry about dropping a paint jar on my foot, not my entire studio being swept away by a flood. But seeing these works brings that possibility, however remote, into sharp focus. It's a reminder to appreciate the stability we often take for granted. However, there's also a complex ethical dimension – can repeated exposure to disaster imagery lead to desensitization, making us less responsive to real-world suffering? It's a question worth pondering as we engage with this kind of art. For me, personally, viewing powerful disaster art often leaves me feeling a profound sense of both fragility and interconnectedness. It's a stark reminder of the forces we can't control, but also of the shared human experience of facing them together.

These pieces can be found in major museums worldwide and smaller local art galleries. Experiencing them in person, feeling the scale and texture, adds another layer to the emotional impact.

Can Art Help After a Disaster?

This is a big question. Can a painting really help someone who has lost everything? Maybe not directly, in the immediate aftermath, but art plays a crucial role in the longer-term recovery and healing process. It's a quiet, often understated, form of resilience. Like finding a single flower pushing through cracked concrete. I've seen firsthand how the simple act of creating, of focusing on something tangible and expressive, can be a lifeline when everything else feels out of control.

- Memorialization: Creating art can be a way to remember what was lost – people, homes, communities. Public art installations or community murals can serve as lasting memorials, honoring victims and preserving the memory of the event and the community's spirit. They become focal points for collective mourning and remembrance.

- Community Building: Collaborative art projects can bring people together, fostering a sense of shared experience, mutual support, and resilience. Working together on a creative project, like painting a mural on a rebuilt community center or creating a collective sculpture from salvaged materials, can be incredibly therapeutic and empowering, helping people connect and rebuild social bonds. These projects can also help preserve cultural memory and identity when physical landmarks are destroyed.

- Raising Awareness: Art can communicate the impact of a disaster to those who weren't there, encouraging support and action. Powerful images or installations can cut through the noise and make people pay attention, prompting donations, volunteer efforts, or policy changes. Art can make the abstract reality of a distant disaster feel immediate and personal.

- Healing: For individuals, the act of creating art, or even just engaging with it, can be profoundly therapeutic. Art therapy is often used in post-disaster settings to help survivors process trauma, express difficult emotions that are hard to put into words, and begin to rebuild their sense of self and the world. It provides a non-verbal language for pain and hope.

- Preserving Cultural Memory: When disasters destroy historical buildings, artifacts, and landscapes, art can play a vital role in preserving cultural memory and identity. Artists can document what was lost, recreate scenes from memory, or create new works that embody the spirit and history of the affected community, ensuring that the past is not entirely erased. This can include documenting traditional practices or creating new narratives through visual means.

- Economic Recovery: While not its primary purpose, art and cultural activities can contribute to the economic revitalization of disaster-stricken areas. Art sales, cultural tourism, and creative industries can provide income and employment opportunities during the rebuilding phase.

Sometimes, just the act of creating, surrounded by your tools, can be a form of healing.

Sometimes, just the act of creating, surrounded by your tools, can be a form of healing.

Contemporary Art and the Climate Crisis

As natural disasters become increasingly linked to climate change, contemporary artists are increasingly addressing this ongoing, global crisis. Their work often moves beyond documenting a single event to exploring broader themes of environmental degradation, human impact, and the potential future of our planet. This can take many forms, from data-driven visualizations of rising sea levels to installations using melting ice or polluted materials, or even performance pieces that highlight human vulnerability to environmental shifts. Artists like Olafur Eliasson have used melting icebergs in public spaces to make the reality of climate change tangible, while others create works from plastic waste collected from oceans. Another example is the work of Chris Jordan, whose photographs of albatross chicks that have died from ingesting plastic debris offer a stark, heartbreaking commentary on the impact of pollution on wildlife and ecosystems, a crisis exacerbated by changing environmental conditions. The work of Maya Lin, known for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, has also turned to environmental themes, creating installations that map endangered rivers or highlight species loss, connecting ecological fragility to collective memory and loss. Artists like John Akomfrah use multi-screen video installations to explore themes of migration, climate change, and the ocean, creating immersive and often unsettling experiences. This art serves not only as commentary but also as a call to action, urging viewers to confront the reality of climate change and its role in intensifying natural disasters. It's a powerful reminder that the storm isn't just a one-time event, but potentially a changing, ongoing reality.

Contemporary public art can often address pressing issues like the environment.

Frequently Asked Questions About Art and Natural Disasters

Q: Is it appropriate for artists to profit from art about natural disasters?

A: That's a tricky one, isn't it? This is a complex ethical question. Many artists create such work to raise awareness or funds for relief efforts, donating proceeds. Others may create work as a personal response. The appropriateness often depends on the artist's intent, how the work is presented, and whether it exploits or genuinely reflects on the human experience of the disaster. There's also the question of who gets to tell the story – is it more appropriate for artists from the affected community to create the work, or can outsiders offer valuable perspectives? It's a dialogue without easy answers.

Q: Where can I see famous examples of art depicting natural disasters?

A: Good question! You can find relevant works in museums with strong collections in periods like Romanticism (for storms, shipwrecks, volcanoes) or those focusing on historical events. Museums with significant collections of modern art and contemporary art may feature works addressing 20th and 21st-century disasters or the climate crisis. Look specifically in photography collections, prints and drawings departments, or contemporary wings. Search museum databases online using keywords like "storm," "flood," "earthquake," "volcano," "shipwreck," or the names of specific historical events. Major institutions like the Louvre, the Tate Modern, or the Metropolitan Museum of Art hold vast collections where relevant pieces might be found, even if not explicitly labeled "disaster art." Don't forget photography museums like The Photographers Gallery or the European House of Photography, which often house powerful documentary images. You might also find relevant works in museums focusing on specific regions prone to certain disasters, or in exhibitions specifically curated around themes of nature, climate, or social impact. Online archives and digital collections can also be valuable resources.

Museums like the Louvre hold countless stories, some of which touch upon humanity's struggle with nature.

Q: How do different cultures approach depicting natural disasters in art?

A: Responses vary widely based on cultural beliefs, historical context, and the specific nature of the disasters faced. Some cultures may emphasize spiritual or mythological interpretations, others focus on human resilience and community, while modern approaches might prioritize scientific understanding or political commentary. Exploring art from regions frequently impacted by specific disasters (e.g., earthquake art in Japan, hurricane art in the Caribbean) can reveal diverse perspectives. Historically, depictions might be tied to religious explanations or divine wrath, while contemporary globalized art often focuses on shared human vulnerability and the need for collective action. The way a culture experiences and understands a disaster is deeply reflected in the art it produces in response.

Q: How has technology impacted disaster art?

A: Technology has profoundly changed how disaster art is created, shared, and experienced. Digital art, video installations, and virtual reality can immerse viewers in simulated environments or present data in compelling visual ways. Social media allows for immediate sharing of photographic and video documentation, turning ordinary citizens into witnesses and creators of powerful, albeit raw, visual records. Online platforms also facilitate global collaboration on art projects and enable artists to reach a wider audience for awareness and fundraising efforts. The speed and reach of digital media mean that responses to disasters can be almost instantaneous and globally distributed.

Q: What role does scale play in depicting disasters?

A: Scale is huge! Literally and figuratively. Artists grapple with capturing the immense physical scale of events like tsunamis or volcanic eruptions, often dwarfing human figures or structures to emphasize nature's power. But scale also refers to the human impact – depicting the vast number of lives affected, the widespread destruction, or the sheer emotional weight of collective trauma. Artists use scale in composition, the size of the artwork itself, and the details (or lack thereof) to convey the overwhelming nature of these events.

Q: How can I support artists who create work related to natural disasters?

A: You can support them by purchasing their work (especially if proceeds go to relief), attending exhibitions, sharing their work online, or supporting organizations that commission or display such art. If you're looking to buy art, consider seeking out artists whose work resonates with you on a deeper level, perhaps even those who tackle challenging themes. Engaging with their work, discussing it, and promoting it also provides valuable support. Look for artists from affected communities or those who work with relevant non-profits.

Q: What makes a disaster artwork particularly impactful or memorable?

A: For me, impact often comes from authenticity and emotional resonance. It's not just about showing destruction, but about conveying the human experience – the fear, the loss, but also the resilience and hope. Art that feels genuine, whether through raw emotion in an expressionist piece, the stark reality of a photograph, or the symbolic power of an installation, tends to stick with you. It connects you to the event and the people affected on a deeper level, often prompting reflection or action.

Q: Can beauty be found or depicted in disaster art?

A: This is a complex and often debated question. While the subject matter is inherently tragic, artists may find and depict moments of stark beauty in the raw power of nature, the resilience of the human spirit, or the unexpected patterns of destruction. This isn't about glorifying suffering but acknowledging the complex reality and finding visual language for the full spectrum of experience, including the awe-inspiring (and terrifying) aspects of nature's force. It requires sensitivity and careful consideration to avoid aestheticizing trauma.

Q: How does art about natural disasters differ from art about human-caused environmental disasters?

A: While there's overlap, art about natural disasters often focuses on humanity's vulnerability to external forces and themes of survival, loss, and resilience in the face of uncontrollable events. Art about human-caused environmental disasters (like pollution, deforestation, or climate change) tends to focus more on critique, responsibility, systemic issues, and calls for action to change human behavior. Contemporary art increasingly blurs this line as natural disasters are linked to climate change, addressing both the immediate impact and the underlying human causes.

Conclusion: Art as a Compass in the Storm

Art about natural disasters serves as a powerful compass, helping us navigate the turbulent waters of loss, fear, and uncertainty that these events bring. It reminds us of our shared vulnerability, celebrates the resilience of the human spirit, and offers a space for reflection and healing. It also challenges us to confront difficult truths, whether about the power of nature or our own impact on the planet.

It's a reminder that even in the face of overwhelming destruction, the urge to create, to understand, and to connect endures. It's a testament to the power of art itself – not just to decorate a wall, but to help us make sense of the world, even when it feels like it's falling apart. For me, exploring these themes, the raw emotion and energy of the world around us, is a vital part of my own artistic journey, a journey you can read more about on my timeline. It's about finding that raw energy, that feeling of the sublime, and translating it into something tangible, something that speaks to others. I hope this exploration encourages you to seek out and engage with this powerful form of art, and perhaps even reflect on your own relationship with the immense forces of nature. And if you're ever in the Netherlands, consider visiting my museum in 's-Hertogenbosch – you might find some pieces that, while not depicting disasters, speak to the raw emotion and energy I try to capture in my own work, the kind of energy that reminds me of the power of nature, both beautiful and terrifying.