What is Art? Ultimate Guide to Definition, Meaning, History & Key Examples

Go beyond the famous few! Explore fascinating, lesser-known art movements like Fauvism, Dada, Constructivism, and more in this personal, engaging guide. Discover hidden gems that shaped art history.

Beyond the Famous Few: Art Movements You Might Not Know (But Totally Should!)

Okay, let's be honest. When someone says 'art movement', your brain probably jumps straight to the big leagues: Impressionism (Monet's water lilies, check), Cubism (Picasso's weird faces, check), maybe Surrealism (Dali's melting clocks, double check). And fair enough, they're famous for a reason. They changed the game, shifted perspectives, and gave us art that's still plastered on postcards and dorm room walls worldwide.

But art history, like any history, isn't just about the headliners. It's a sprawling, messy, interconnected web of ideas, reactions, and experiments. Sometimes I feel like I know less the more I learn, which is both frustrating and kind of exciting. There's always more hiding just around the corner. I remember stumbling upon a book about the Bauhaus movement years ago, expecting something dry and academic, and instead being completely blown away by its radical ideas about integrating art and life. It totally shifted how I thought about design and creativity. That's the magic of digging a little deeper.

Think of it like music – everyone knows The Beatles or Beyoncé, but there’s a whole universe of incredible indie bands, niche genres, and forgotten pioneers that offer just as much, sometimes even more, satisfaction once you find them. The art world is no different. Digging a bit deeper reveals movements that were radical, beautiful, weird, and incredibly influential, even if they don't have the same blockbuster museum exhibitions.

So, let's put on our explorer hats (metaphorically, unless you actually own one, in which case, rock it) and dive into some art movements you might not know, but definitely should.

Why Bother With the Obscure Stuff?

I get it. Time is limited. Why spend energy on movements that aren't household names? Well, for a few reasons:

- Deeper Understanding: Knowing these lesser-known movements provides crucial context for the famous ones. Art doesn't happen in a vacuum; it's a conversation across time. Understanding Fauvism enriches your appreciation of later Expressionism. It's like understanding punk rock to really get grunge.

- Discovering New Loves: You might find your absolute favorite style isn't Impressionism, but something like Orphism or Synchromism. Broadening your horizons increases the chances of finding art that truly speaks to you. Maybe you'll find a style that just clicks with your soul, like finding that perfect, slightly obscure band.

- Appreciating the Process: Seeing these 'in-between' or less commercially successful movements highlights the experimentation and risk-taking inherent in art. It's not always about ending up in the MoMA. It's about the journey, the pushing of boundaries, the glorious failures, and the quiet revolutions.

- Inspiring Your Own Creativity: As an artist myself, exploring these diverse approaches is like filling up a creative well. Seeing how artists tackled color in Fauvism, structure in Constructivism, or pure emotion in Expressionism gives me new ideas for my own work. It reminds me there are infinite ways to see and create.

- Sounding Smart (Optional but Fun): Casually dropping 'Orphism' into conversation? Instant art cred. (Use responsibly. Don't be that person... unless you want to be. No judgment here.)

Alright, enough preamble. Let's meet some of these fascinating artistic side-quests.

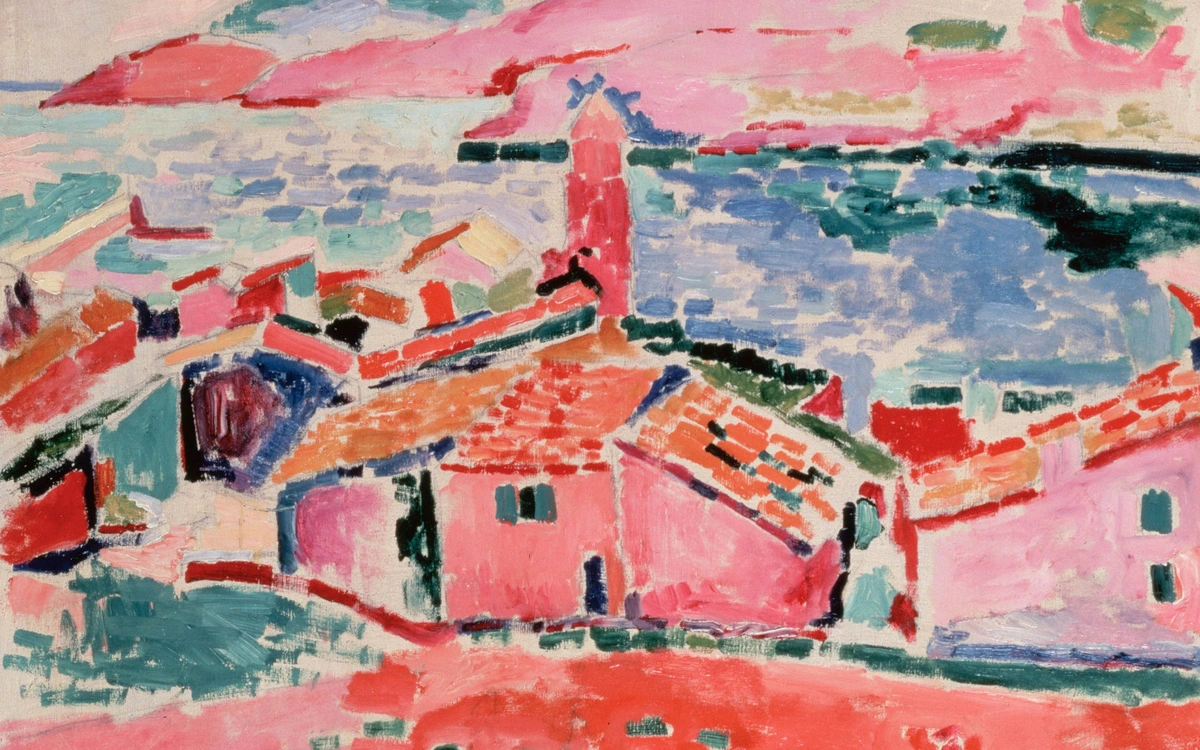

Fauvism: The Wild Beasts of Color

Imagine telling painters, steeped in the subtle light of Impressionism, to just unleash pure, unadulterated color straight from the tube. That's kind of what Fauvism did around the turn of the 20th century. It was a roar of color against the gentle Impressionist whisper.

What Was It?

Led by artists like Henri Matisse and André Derain, Fauvism was all about intense, non-naturalistic color and bold, often spontaneous brushwork. But it wasn't just about slapping paint on the canvas. The Fauves also embraced simplified forms and a flattened perspective, moving away from traditional representation. Forget realistically depicting a scene; the Fauves used color to express emotion and create a powerful visual impact. Trees could be red, skies orange, faces green – whatever felt right, whatever conveyed the feeling of the scene rather than its literal appearance. They were heavily influenced by the expressive use of color by Post-Impressionists like Gauguin and Van Gogh, taking those ideas and running wild with them. The name itself means 'wild beasts' in French, a term coined (initially derisively) by a critic shocked by their vibrant canvases at the 1905 Salon d'Automne in Paris. Honestly, I kind of love being called a 'wild beast' for using too much color. It feels right.

Why It Matters

Though short-lived as a formal movement (roughly 1905-1908), Fauvism's liberation of color was revolutionary. It paved the way for Expressionism and influenced countless modern artists. It reminds us that art isn't just about copying reality, but interpreting and heightening it. Sometimes you just need to let the colors roar. You can explore Fauvism in more detail in our Ultimate Guide to Fauvism.

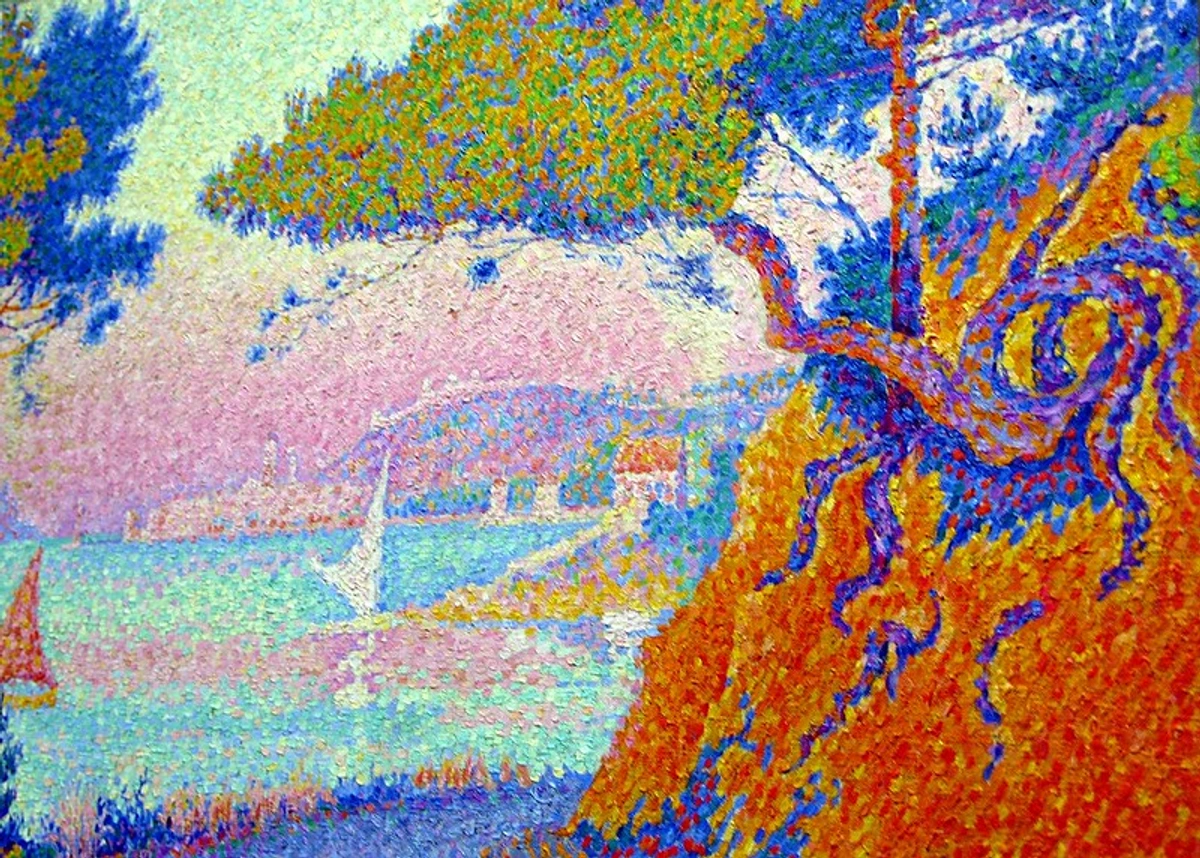

Pointillism / Neo-Impressionism: The Science of Dots

While the Fauves were painting with instinct and emotion, others sought a more calculated approach. Okay, maybe you've heard of this one, or at least seen Georges Seurat's massive, dot-filled park scene. But Pointillism (or the more formal Neo-Impressionism) is more than just one famous painting. It's a testament to patience and color theory.

![]()

What Was It?

Emerging in the 1880s with Georges Seurat and Paul Signac at the helm, Neo-Impressionism took the Impressionists' interest in light and color a step further, applying scientific theories about optics. Instead of mixing colors on the palette, they applied small, distinct dots of pure color directly onto the canvas. The idea was that these dots would blend in the viewer's eye (optical mixing), creating more vibrant and luminous results than pre-mixed pigments. Why? Because light reflecting off tiny dots of pure color was believed to be brighter and more intense than light reflecting off colors already dulled by mixing on a palette. It's like the pixels on your screen! Other artists who experimented with this demanding technique included Camille Pissarro (for a period) and Henri-Edmond Cross.

Why It Matters

Pointillism represented a more calculated, almost scientific approach compared to the spontaneity of Impressionism. It required immense patience (imagine painting a huge canvas dot by dot – makes my hand hurt just thinking about it) and a deep understanding of color theory. While the technique itself was demanding, its focus on the 'building blocks' of color influenced later abstract movements and even graphic design. It's a reminder that sometimes, breaking things down into their smallest components can reveal something new and brilliant. Check out our Ultimate Guide to Pointillism for more.

Orphism / Synchromism: Abstracting Color and Music

Taking the exploration of color even further, these two movements popped up around the same time (roughly 1912-1914) and are so similar they're often discussed together. Think Cubism, but make it about pure color and rhythm. They took Cubism's fragmentation of form but rejected its often monochromatic palette, opting instead for a full-blown color party.

What Was It?

Orphism, primarily associated with Robert Delaunay and Sonia Delaunay in Paris, aimed for pure painting by abandoning recognizable subject matter. They focused on pure abstraction through vibrant, contrasting colors and geometric shapes (especially circles), believing color itself could be the subject. They were inspired by the idea that color harmonies could evoke feelings similar to music (hence 'Orphism', referencing the mythical musician Orpheus). They sought to translate musical concepts like harmony, rhythm, and counterpoint into visual terms, using the interplay of colors and forms to create a dynamic, non-representational experience for the viewer. Imagine a symphony, but instead of notes, it's made of swirling, vibrating colors.

Synchromism ('with color'), developed by American artists Stanton Macdonald-Wright and Morgan Russell (also in Paris), had almost identical goals: creating abstract art based solely on color relationships and rhythms, often drawing analogies to musical composition. It's fascinating how similar ideas can emerge simultaneously in different places.

Why It Matters

Orphism and Synchromism were among the very first purely abstract art movements. They pushed the boundaries by insisting that color alone, arranged dynamically, could be as compelling and meaningful as representational art. Their work is a joyful explosion of color and form, a precursor to much later abstract art. They remind us that art doesn't always need to show you something; sometimes it just needs to feel like something.

Constructivism: Art for a New Society

Moving from the purely aesthetic to the intensely practical and political, we find Constructivism. Born out of the revolutionary ferment in Russia around 1913, Constructivism wasn't just an art style; it was an ideology. Art was seen as a tool to build a better world.

![]()

What Was It?

Artists like Vladimir Tatlin, Alexander Rodchenko, and El Lissitzky rejected the idea of 'art for art's sake'. They believed art should serve a social purpose, contributing to the construction of a new communist society. This was art deeply intertwined with the ideals and propaganda needs of the early Soviet state. Constructivism emphasized geometric abstraction, industrial materials (metal, glass, plastic), and functional design. Think bold typography, photomontage, dynamic compositions, and utilitarian objects rather than traditional easel painting or sculpture. Their principles were applied across a huge range of media: posters, book covers, furniture, textiles, clothing design, architecture, and even theatre sets. It was about art integrated into everyday life, not confined to galleries.

Why It Matters

Constructivism fundamentally linked art with social and political goals. It blurred the lines between fine art and design, influencing graphic design, architecture, photography, and theatre design for decades. Its visual language still feels modern and impactful today, a powerful example of how art can be a force for change (or propaganda, depending on your perspective). It also stands in contrast to the academic art of the time, which often clung to traditional subjects and styles, highlighting the radical break these movements represented.

Suprematism: The Supremacy of Pure Feeling

Emerging alongside Constructivism in Russia, Suprematism shared the interest in geometric abstraction but had a very different philosophical aim. Founded by Kazimir Malevich around 1915, it was less about building a new society and more about exploring pure artistic feeling.

![]()

What Was It?

Malevich sought to create an art that was 'supreme' in its purity, free from any representation of the objective world. He believed that the most fundamental artistic elements were the square, the circle, the triangle, and the cross, rendered in a limited palette of colors (often black, white, and red). His famous Black Square (1915) is considered a foundational work, representing the 'zero point of painting' – a radical break from everything that came before. Suprematism was about the spiritual and emotional experience evoked by pure form and color, not about depicting reality or serving a function. It was art for the sake of art, taken to an extreme.

Why It Matters

Suprematism was a crucial step towards pure abstraction and had a significant impact on the development of abstract art, particularly in its emphasis on geometric forms and minimalist aesthetics. While its philosophical underpinnings can be a bit dense, the visual impact of its stark, powerful compositions is undeniable. It challenged viewers to find meaning and feeling in form and color alone, a challenge that continues to resonate in abstract art today.

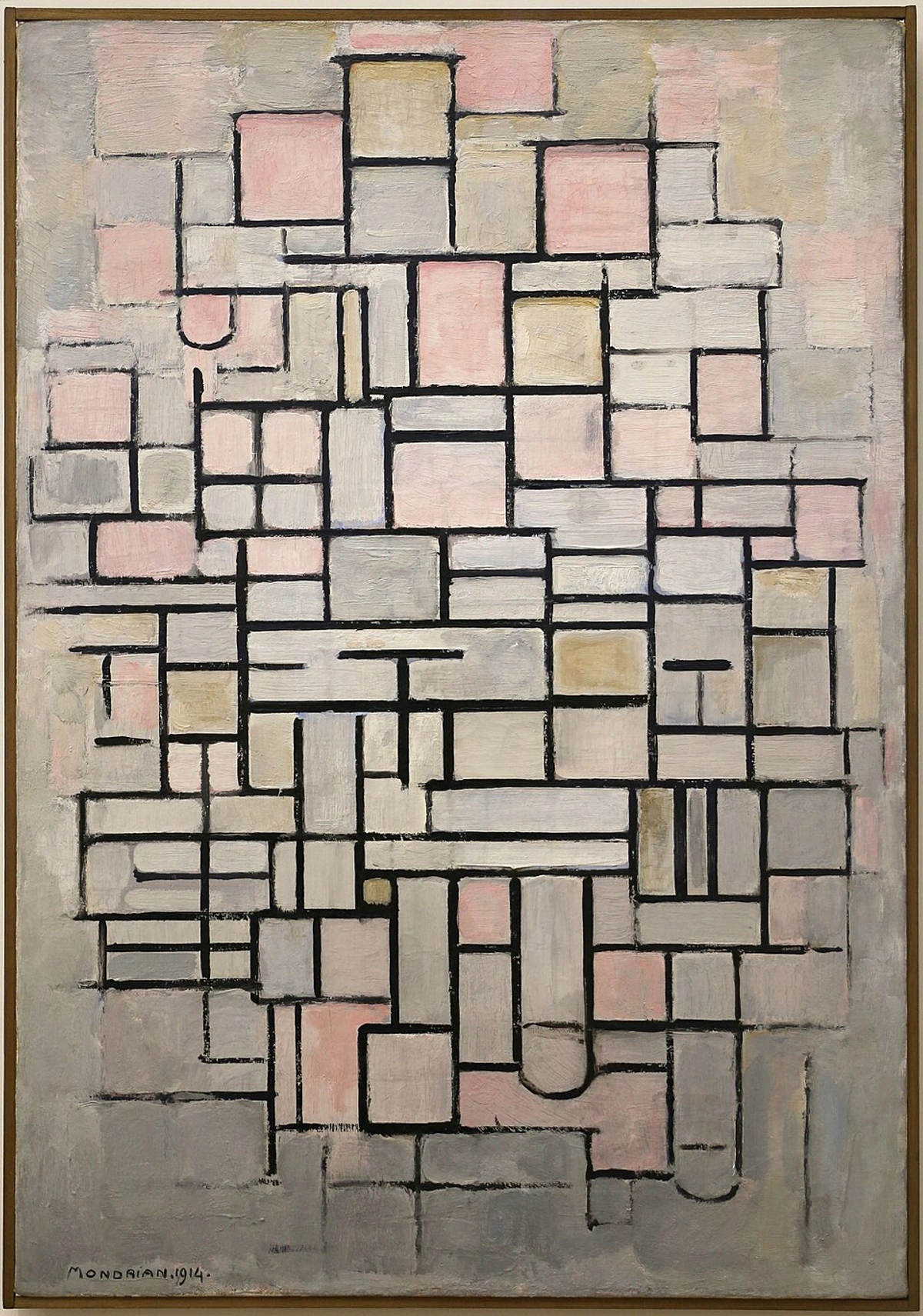

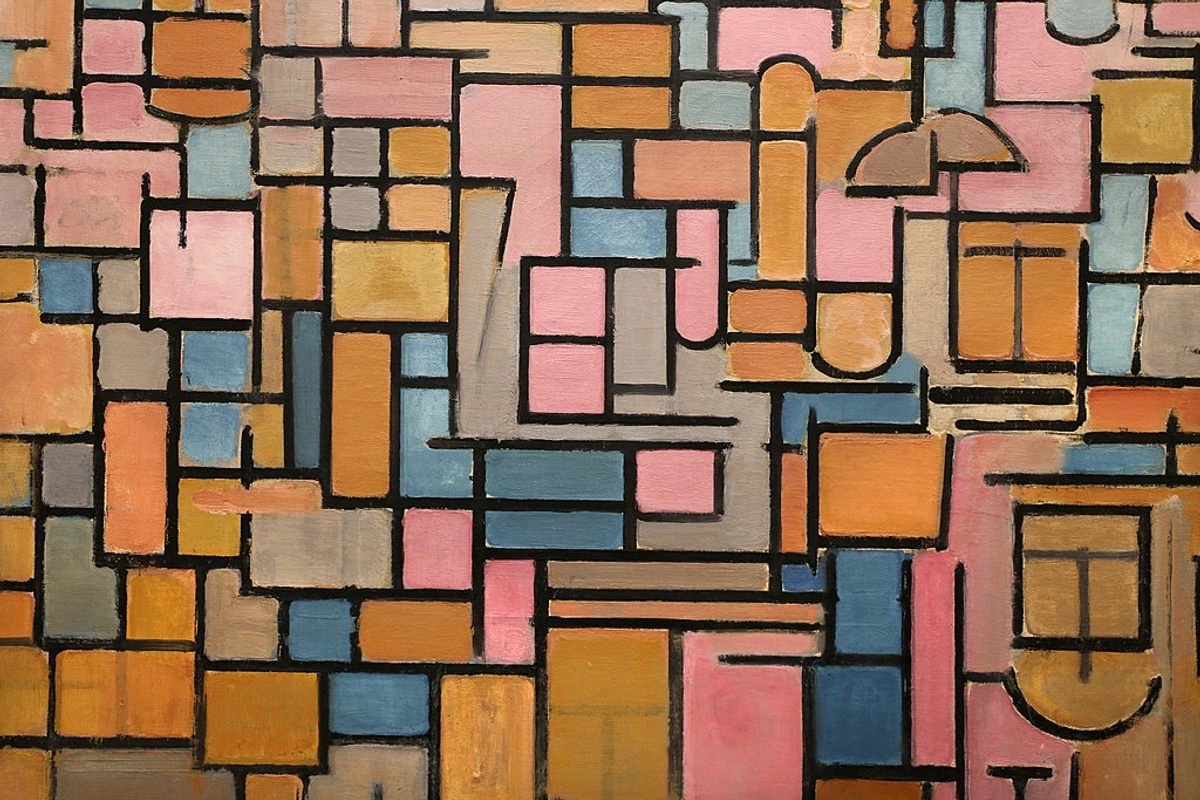

De Stijl: Harmony and Order

Across Europe, another group of artists was also exploring geometric abstraction, but with a focus on harmony, order, and universal principles. De Stijl (Dutch for 'The Style'), founded in the Netherlands in 1917 by Theo van Doesburg and including Piet Mondrian, sought a utopian vision through art.

What Was It?

De Stijl artists aimed for a pure, abstract art based on the most fundamental visual elements: straight lines (horizontal and vertical), primary colors (red, yellow, blue), and non-colors (black, white, gray). They believed that by reducing art to these essentials, they could create a universal visual language that reflected underlying cosmic harmony and order. Like Constructivism, De Stijl wasn't confined to painting; its principles were applied to architecture, furniture design, typography, and even clothing. Mondrian's famous grid compositions are the most recognizable examples, but the movement's influence can be seen in everything from modern architecture to graphic design.

Why It Matters

De Stijl's rigorous approach to abstraction and its emphasis on universal harmony had a profound impact on modern design and architecture. It championed clarity, order, and functionality, influencing movements like the Bauhaus. It's a fascinating example of how a seemingly simple set of rules (only straight lines and primary colors!) could lead to such a wide range of creative output, all aimed at creating a more balanced and harmonious world. It's proof that sometimes, constraints can actually fuel creativity.

Dadaism: Art as Anti-Art

If Constructivism wanted to build a new world with art, and Suprematism/De Stijl sought universal harmony, Dadaism wanted to tear the old one down – or at least mock it mercilessly. Born during the chaos of World War I (around 1916) in Zurich, and spreading to Berlin, Paris, and New York, Dada was less a style and more an attitude. It was a scream of protest against the absurdity of a world that could descend into such violence.

![]()

What Was It?

Dadaists like Marcel Duchamp, Tristan Tzara, Hannah Höch, and Kurt Schwitters reacted to the absurdity and horror of the war by rejecting logic, reason, and traditional aesthetic values. Their work embraced chance, irrationality, nonsense, and protest. The movement famously began at the Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich, a hub for artists and writers seeking refuge from the war. Key techniques included the readymade (presenting ordinary objects as art, like Duchamp's urinal, titled Fountain), photomontage (creating new images by cutting and pasting photographs), collage, and sound poetry. Dada wasn't monolithic; it had different flavors in different cities. Berlin Dada, for instance, was highly political and critical of German society, while Zurich Dada was more focused on performance, poetry, and abstract art. It was provocative, often humorous (dark humor, naturally), and deeply critical of bourgeois society and the established art world. They basically asked,