The Scream Meaning: Unraveling Edvard Munch's Iconic Artwork

Explore the profound meaning behind Edvard Munch's 'The Scream'. Delve into its Symbolist and Expressionist roots, personal inspiration, and enduring cultural impact.

The Scream by Edvard Munch: An Ultimate Guide to Its Profound Meaning and Enduring Legacy

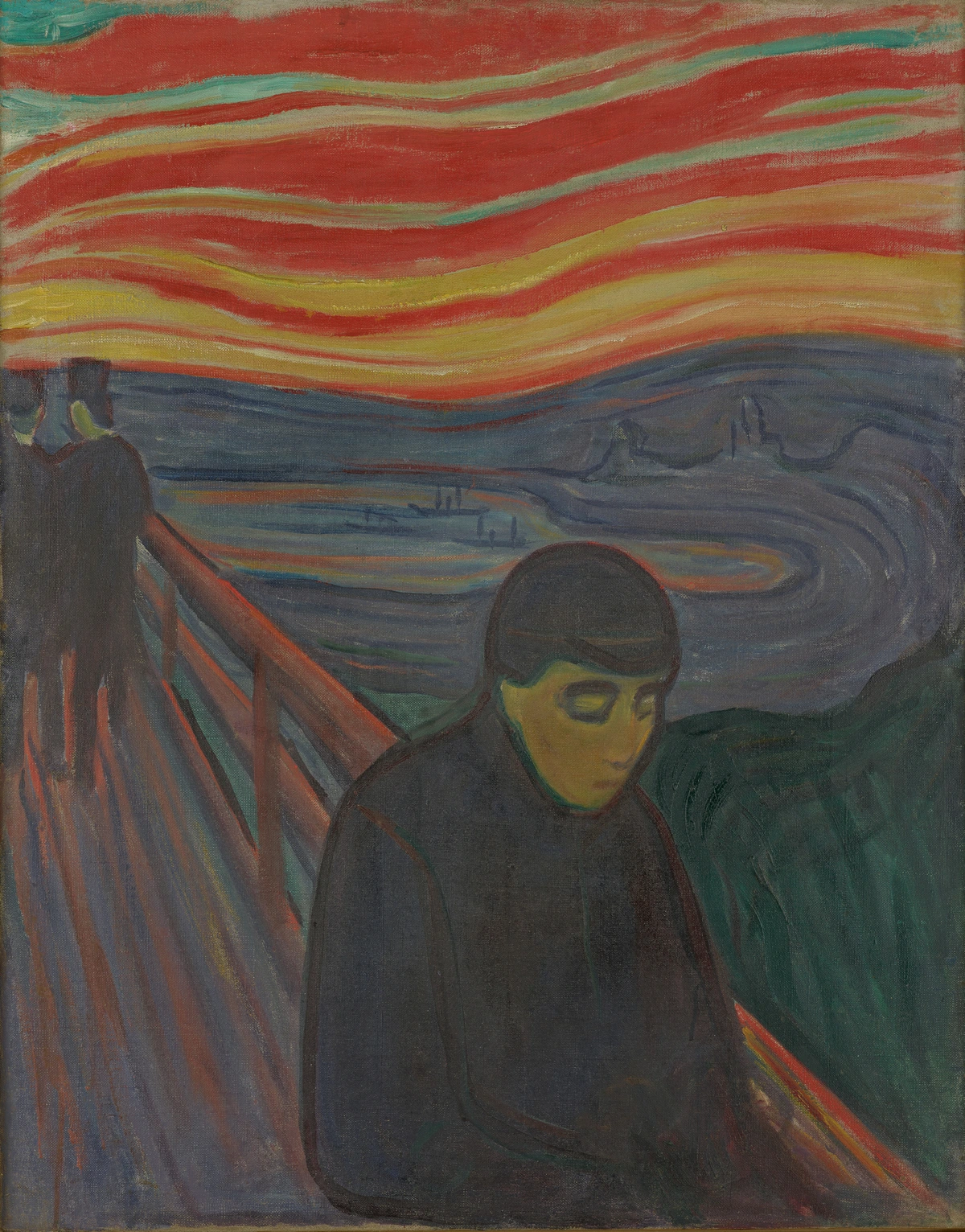

I've always been captivated by artworks that don't just whisper, but scream emotion, pieces that articulate the inarticulable anxieties of the human condition. And few, if any, paintings achieve this with the raw, gut-wrenching power of Edvard Munch's iconic The Scream. It's far more than just paint on canvas; it’s a chillingly prophetic embodiment of universal human anxieties, a visceral vision of modern existential dread, and for me, a piece that makes you feel profoundly seen, even amidst its terror. From the moment it was first exhibited, The Scream ignited both fervent controversy and deep fascination, instantly carving out a unique, unsettling space in the art world. As a curator of human experience, I find this work absolutely essential to understand. Its initial reception, too, is a fascinating lens into the shifting sensibilities of its era, revealing a society grappling with its own unspoken fears. This isn't just a guide; it’s an exhaustive, meticulous unraveling of this masterpiece's multifaceted layers. We'll explore everything from its deeply personal origins in Munch's tormented psyche and the unsettling cultural climate of the Fin de Siècle, to its groundbreaking visual language that pioneered Expressionism and irrevocably shifted the course of modern art, and its enduring, almost inescapable, legacy in contemporary consciousness. Here, we’ll delve into The Scream's profound artistic and historical significance, exploring its unparalleled capacity to articulate the unspoken fears that reside within the human experience, and its monumental place in the annals of psychological art history. Prepare to gain a deeper, more visceral appreciation for this masterpiece's enduring power and its continued, almost alarming, relevance in our complex modern world. It's a scream that still echoes.

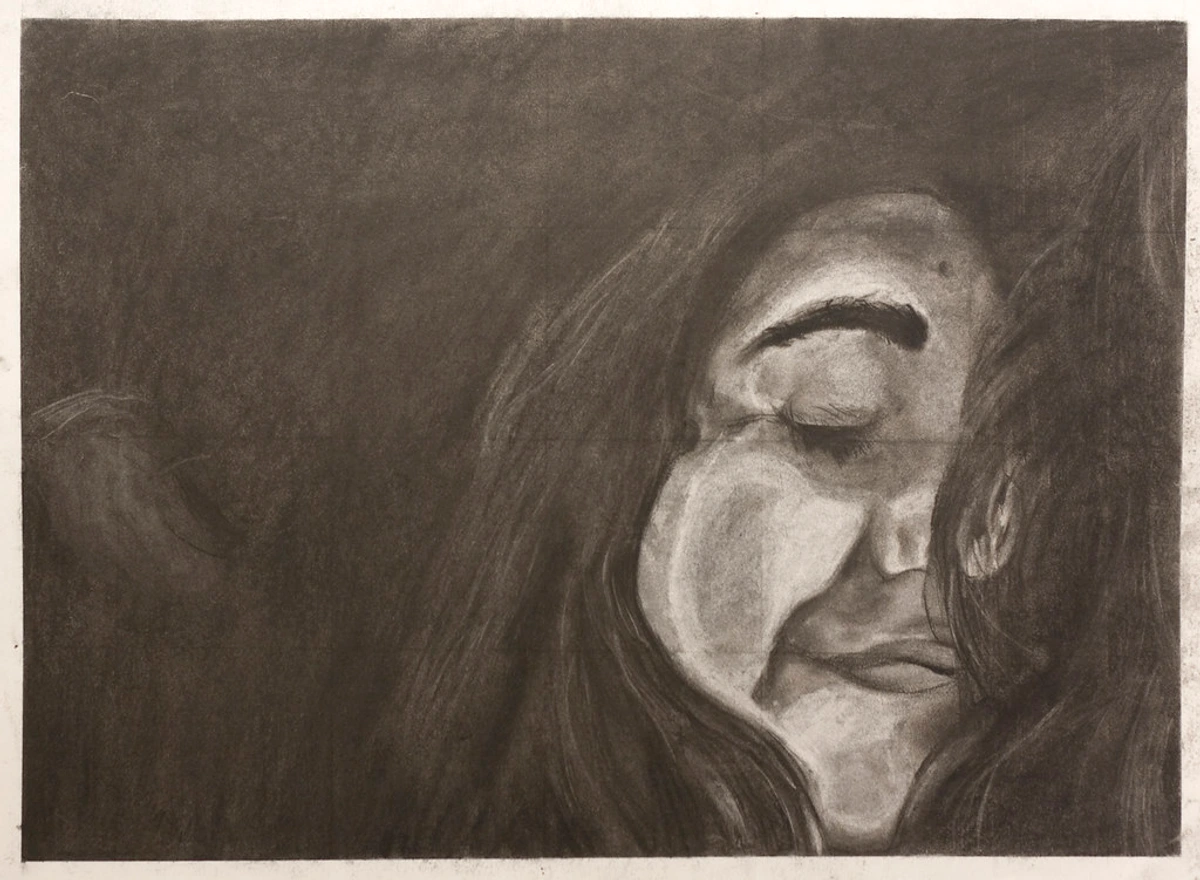

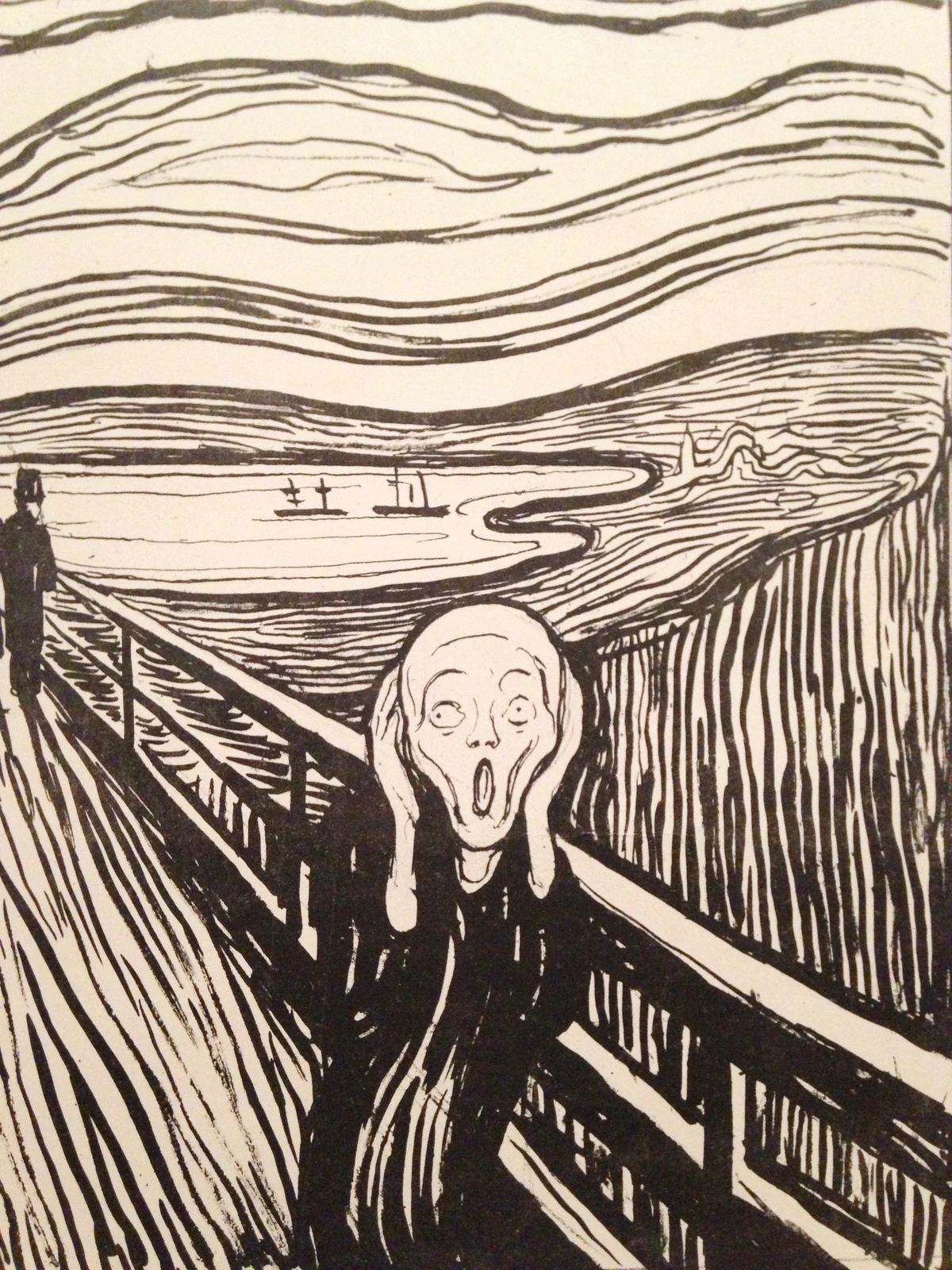

The Lithographic Scream: Democratizing Anguish and Amplifying Message

While the painted and pastel versions of The Scream are undoubtedly its most famous, Edvard Munch’s creation of a lithographic stone in 1895 is, in my view, equally, if not more, significant for its radical implications. This black and white print version wasn't just another iteration; it was a revolutionary act that allowed for the widespread dissemination of the image, breaking it free from the confines of elite galleries. Think about it: it transformed The Scream from a unique, singular art object into a reproducible, almost democratic, icon, capable of reaching an unprecedented audience. Through lithography, Munch wasn't just making copies; he was able to strip the image down to its rawest graphic lines, emphasizing pure form and stark contrast in a way that paint couldn't quite achieve. This technique, relying on the greasy interaction of ink and water on a stone surface, enabled him to capture the primal anguish with a stark immediacy and graphic punch that differed subtly from the painterly qualities of the other versions. The multiple prints made from this stone further democratized The Scream's powerful, unsettling message, making it accessible to a broader audience far beyond the exclusive art world. This forward-thinking approach to artistic reproduction, almost anticipating the mass media and viral spread of images in our digital age, cemented its place in public consciousness and solidified its status as a global icon. I find it fascinating how Munch, through this early adoption of printmaking, was able to control the narrative and reach a wider public, profoundly amplifying the artwork's message of universal anxiety.

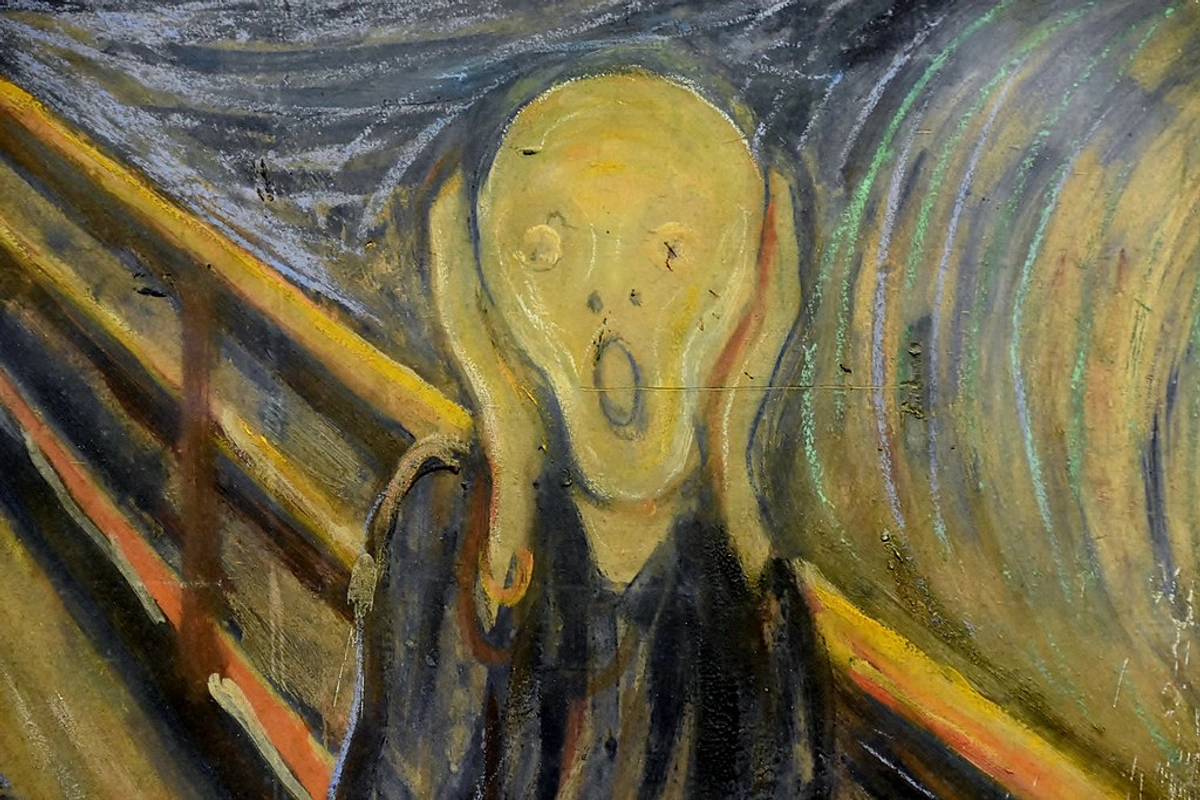

credit, licenceThe Scream, 1893, National Gallery, Oslo](https://images.zenmuseum.com/article/why-is-edvard-munchs-the-scream-famous/dad7f400-ab29-11f0-b627-9dcb4bd4c069.jpg)

Munch's Artistic Process and Vision: Translating Emotion into Form and the Frieze of Life

Edvard Munch’s artistic process was, to put it mildly, deeply unconventional for his time. It wasn't driven by academic adherence to realistic representation, which was still very much the norm in many circles. Instead, it was fueled by an urgent, almost therapeutic need to externalize his inner emotional landscape. For Munch, art was never just about beauty or skill; it was a profound means of self-expression, a way to grapple with the anxieties and traumas that relentlessly plagued his life. He famously stated, "I paint not what I see, but what I saw." This philosophy profoundly shaped every aspect of his approach to composition, color, and line, making his work intensely subjective and emotionally charged. It’s almost as if he was painting a memory, a feeling, a haunting echo, rather than a mere scene.

He often revisited the same motifs over many years – a testament, I think, to the persistent power of his inner visions and a psychological necessity – creating multiple versions of his most iconic works in different mediums: paintings, pastels, lithographs, and woodcuts. This iterative process wasn't a sign of indecision but a deliberate, almost obsessive, exploration, a way to chase down the elusive core of an emotion. For Munch, each new version, whether a subtle shift in color or a bold change in medium, offered a fresh opportunity to refine its visual language and achieve maximum psychological impact. His goal was never merely to depict; it was to evoke, to make the viewer feel the same intensity of emotion that he himself experienced. This dedication to psychological truth, even at the expense of conventional beauty, truly marks him as a revolutionary figure in modern art, a true pioneer of emotional realism. It's almost like he was building a visual lexicon for his own soul, piece by piece, as part of his ambitious "Frieze of Life" series, which aimed to explore the fundamental themes of existence – birth, love, sickness, anxiety, and death.

The Genesis of a Scream: Munch's Personal Anguish and the Fin de Siècle Mood

To truly comprehend The Scream, I believe one must delve deeply into the life of Edvard Munch himself. Born in Løten, Norway, in 1863, his existence was, to say the least, relentlessly tragic, profoundly shaping his artistic vision. Imagine: at age five, he lost his mother. Just nine years later, his beloved sister Sophie succumbed to tuberculosis. Another sister, Laura, suffered from mental illness and was institutionalized, while his father grappled with deep depression and an intense, often terrifying, religious fanaticism, frequently recounting hellfire sermons. These were not just isolated incidents; these deeply traumatic experiences became the crucible in which his extraordinary artistic vision was forged. Rather than crushing him, they fueled his urgent need to grapple with universal themes of life, death, love, fear, and a profound, inescapable melancholy through his art. It's almost as if he processed his entire personal catastrophe through his canvas.

His artistic inclinations were nurtured from a young age, leading him to enroll in the Royal School of Art and Design in Oslo. There, he received a relatively traditional art education, focusing on academic realism – the kind of art he would later radically depart from. However, it was his subsequent exposure to the vibrant, often scandalous, bohemian circles of Oslo, and later the avant-garde movements in Paris, that truly catalyzed his departure from convention. These experiences, combined with his continuous personal struggles, moved him decisively away from objective representation towards a profoundly subjective and emotionally charged artistic language. This groundwork was crucial for his seminal works, positioning him as an undeniable forerunner of the nascent Expressionist movement.

Munch's intensely personal torments resonated eerily with the wider mood of the Fin de Siècle, the "end of the century" in Europe. This wasn't just a calendar change; it was a period of widespread societal unease, spiritual angst, and a deep, almost morbid, fascination with the darker, more unsettling aspects of the human psyche. Think of it: contemporaries like playwrights Henrik Ibsen and August Strindberg, and poets like Charles Baudelaire, similarly explored themes of human despair and alienation in their work. Philosophers like Friedrich Nietzsche were questioning traditional morality, declaring the "death of God," which certainly didn't help with spiritual comfort. Meanwhile, the rapid advance of industrialization brought new forms of alienation and an existential void, challenging traditional values and creating a profound sense of fragmentation. It was a world in flux, a world often teetering on the edge of chaos. This rich cultural backdrop, intertwined with Munch’s own struggles, positioned him as an exceptionally sensitive interpreter of the modern condition, uniquely capable of articulating the invisible anxieties swirling through society and setting the stage for his intensely personal artistic expressions. It was as if the collective subconscious found its visual voice in his art. The specific geographical location of Munch's seminal experience, Ekeberg Hill, a prominent vantage point overlooking the Oslofjord and the bustling city of Oslo, also plays a symbolic role. This wasn't some remote, exotic locale; this was a familiar, seemingly idyllic landscape, yet it became the stage for Munch's profound psychological rupture. The very act of walking along this particular road, a routine activity, was suddenly imbued with terrifying existential significance as the artist perceived the natural world itself to be screaming. And here's a detail I find particularly chilling: the Ekeberg area, incidentally, also had a history as a place associated with mental institutions and a local slaughterhouse. Elements that, I believe, some art historians compellingly argue subconsciously contributed to the underlying sense of dread and despair that Munch captured so powerfully. This layering of personal trauma, philosophical angst, and deeply unsettling environmental resonance makes the location itself an integral, symbolic element of The Scream, serving as a concrete, yet terrifying, backdrop to an intensely abstract and internal experience. It's as if the very ground held a memory of suffering.

The Synesthetic Inspiration: Munch's Diary Entry and the Krakatoa Connection

Now, for the aha! moment, the direct, almost hallucinatory inspiration for The Scream is famously documented in Munch's poignant diary entry from January 22, 1892 (though some art historians cite 1893 as the year of initial conception for the first version, particularly for the first painted version). This entry, for me, provides a crucial, intimate window into the artist's subjective experience, detailing a moment of intense, almost synesthetic terror that directly led to the iconic image:

"I was walking along the road with two friends – the sun was setting – suddenly the sky turned a blood red – I paused, feeling exhausted, and leaned on the fence – there was blood and tongues of fire above the blue-black fjord and the city – my friends walked on, and I stood there trembling with angst – and I sensed an infinite scream passing through nature."

This visceral account paints a picture of profound psychological rupture. It’s a moment of profound synesthetic experience, where visual stimuli – that blood-red sky – triggered an overwhelming auditory and emotional sensation: the scream passing through nature. That "blood red" sky is not just a visual phenomenon; it's a potent symbol of internal turmoil, a sense of cosmic horror that completely overwhelms the individual. Munch's choice of words—"blood," "tongues of fire," "trembling with angst"—evokes a sense of apocalyptic dread, transforming a natural event into a deeply personal and terrifying omen. This profound ability to imbue external reality with internal, emotional significance is a testament to his unique artistic genius and his capacity to find universal meaning in intensely subjective experience. It's crucial to understand: the central figure isn't making the sound; rather, it is responding to the overwhelming "scream" of nature itself, a profound existential tremor that permeated the artist's perception of the world. It's a primal reaction to the world's raw, terrifying indifference. Many art historians find the theory that the intense, blood-red skies depicted could be influenced by the actual atmospheric phenomena witnessed across Europe after the 1883 eruption of the Krakatoa volcano incredibly compelling. This catastrophic volcanic event created vividly colored sunsets for years, and Munch, a keen observer of his environment and internal states, may have subconsciously or consciously integrated these spectacular, unsettling natural displays into his emotional landscape.

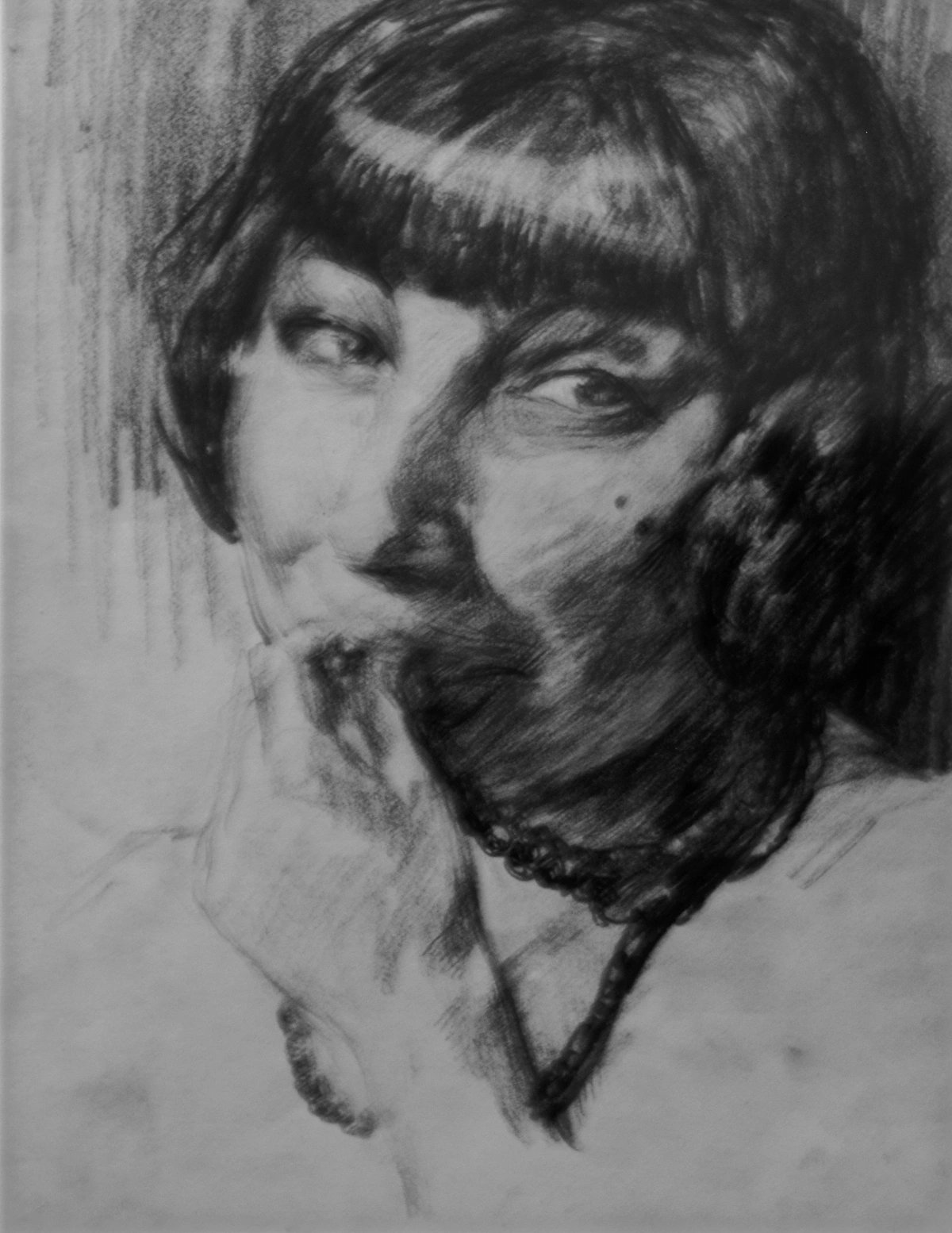

This powerful, synesthetic experience – where Munch felt rather than literally heard the scream – transformed a deeply personal moment of anxiety into a universal artistic statement. I find it so compelling that the central figure is not making the sound; rather, it is responding to the overwhelming "scream" of nature itself, a profound existential tremor that permeated the artist's perception of the world. The landscape itself appears to cry out, and the figure functions as a conduit for that immense, suffocating dread, echoing the philosophical anxieties about humanity's place in an indifferent cosmos. This profound engagement with personal trauma and its translation into universal emotional experience is also evident in the works of artists such as Käthe Kollwitz, whose art captured the anguish of societal commentary and personal loss. Munch's ability to imbue external reality with internal, emotional significance is a testament to his unique artistic genius and his capacity to find universal meaning in intensely subjective experience. It's an internal tremor made visible.

Symbolism of the Figure: Beyond the Scream

Beyond the immediate, gut-wrenching anguish, the central figure in The Scream holds multiple layers of symbolic meaning that contribute to its timeless appeal. The figure's elongated, almost liquid form isn't just a stylistic choice; it suggests a being in the process of dissolution, mirroring, I think, the disintegration of traditional certainties in the rapidly changing modern age. It is a universal 'everyperson,' stripped of specific identity, making its agony profoundly relatable across cultures and centuries. Some interpretations connect the figure directly to Munch's own struggles with mental illness, viewing it as a raw depiction of a mind utterly overwhelmed by internal demons. Others see it as a stark representation of humanity's existential loneliness in an indifferent cosmos, a small, fragile being confronting the vast, terrifying forces of nature and existence itself. The deliberate ambiguity is key here; it ensures that the figure can embody a spectrum of human fears, from intensely personal anxieties to a broader, collective dread, making it a powerful visual shorthand for the human condition itself. This profound engagement with human vulnerability and suffering elevates The Scream far beyond a mere depiction of a moment; it becomes a meditation on the fundamental nature of fear and isolation. It's a mirror reflecting our deepest, unspoken terrors. The striking similarity between the figure's posture and the forms of pre-Columbian Peruvian mummies, with their hands often clasped to their faces, is a detail that art historians often highlight, underscoring the timeless and universal nature of this primal expression of horror and resignation.

Symbolism of the Figure: Beyond the Scream

Beyond the immediate, gut-wrenching anguish, the central figure in The Scream holds multiple layers of symbolic meaning that contribute to its timeless appeal. The figure's elongated, almost liquid form isn't just a stylistic choice; it suggests a being in the process of dissolution, mirroring, I think, the disintegration of traditional certainties in the rapidly changing modern age. It is a universal 'everyperson,' stripped of specific identity, making its agony profoundly relatable across cultures and centuries. Some interpretations connect the figure directly to Munch's own struggles with mental illness, viewing it as a raw depiction of a mind utterly overwhelmed by internal demons. Others see it as a stark representation of humanity's existential loneliness in an indifferent cosmos, a small, fragile being confronting the vast, terrifying forces of nature and existence itself. The deliberate ambiguity is key here; it ensures that the figure can embody a spectrum of human fears, from intensely personal anxieties to a broader, collective dread, making it a powerful visual shorthand for the human condition itself. This profound engagement with human vulnerability and suffering elevates The Scream far beyond a mere depiction of a moment; it becomes a meditation on the fundamental nature of fear and isolation. It's a mirror reflecting our deepest, unspoken terrors.

The Role of Distortion and Exaggeration in Evoking Emotion: A Rebellion Against Realism

Munch's deliberate use of distortion and exaggeration is, in my professional opinion, not a sign of artistic deficiency; it's a sophisticated and radical artistic choice aimed precisely at intensifying emotional impact and challenging the very foundations of academic realism. By elongating the figure, blurring the lines of the landscape, and contorting familiar forms, Munch isn't just messing with objective reality; he's forcing the viewer to confront a deeply subjective, internal reality. This audacious artistic license allows him to bypass the intellect entirely and speak directly to our raw, visceral emotions, creating a profound, almost uncomfortable, intimacy with the artwork. Those swirling lines and fiery colors? They're not meant to be realistically descriptive; they are the visual manifestation of anxiety, panic, and despair made tangible. This technique, a defining hallmark of Expressionism, fundamentally alters the viewer's perception, creating an immersive, almost suffocating, experience of the figure's inner turmoil. It’s a powerful demonstration of how art can move beyond mere representation to embody profound psychological states, making the unseen feelings visible and tangible. It's like a scream you can see, a deliberate rebellion against the academic realism that had dominated for centuries, proving that emotional truth could be more profound, and indeed more impactful, than visual accuracy.

Visual Language of Despair: Deconstructing the Elements of The Scream

Munch masterfully employed a distinct, almost revolutionary, visual language to literally channel the overwhelming emotional intensity of The Scream. Every single component, every brushstroke, contributes to the artwork's unsettling, almost magnetic power. The composition functions as an emotional engine on canvas, driven by a deliberate orchestration of form, color, and line, all designed to convey profound psychological states rather than mere external reality. This intentional distortion and exaggeration of elements are hallmarks of the emerging modernist aesthetic, where subjective experience decisively began to take precedence over objective depiction. I always tell people to look closely at how the lines and colors don't just depict a scene, but rather create a feeling, pulling you right into the figure's inner world, forcing you to confront its anguish as your own.

Every decision Munch made, from the central figure to the swirling landscape, was calculated to amplify the sense of despair and isolation. It’s a symphony of suffering, conveyed through visual cues:

The Central Figure: A Universal Icon of Anguish and Existential Dread

For me, the central figure is undoubtedly the most striking and unforgettable element of The Scream. This androgynous, skeletal figure, dominating the foreground, clutches its head with elongated, almost boneless hands, its mouth agape in a silent, yet profoundly deafening, shriek. The deliberate gender ambiguity isn't accidental; it strips away specific identity, rendering the anguish universal – a representation of humanity itself, flayed to its rawest emotional core. The figure's distorted, almost fetal appearance, with its hollowed eyes and skull-like face, powerfully conveys profound vulnerability and primal terror, embodying humanity reduced to a pure, unadulterated scream. A crucial detail, one I always point out, is the hands pressed firmly against the ears, suggesting a desperate, futile attempt to block out an overwhelming cry – whether an internal scream, the literal scream of nature Munch experienced, or the unsettling sounds of his own psyche. This act amplifies themes of isolation and the crushing futility of escaping inner torment. The figure is not merely witnessing a scream; it embodies the "scream" itself, becoming a conduit for an overwhelming existential feeling rather than its source. It's a truly brilliant move. Art historians often draw parallels between its isolated anguish and pre-Columbian Peruvian mummies, noting the similar posture and expression of eternal horror – a connection that speaks volumes about the timelessness of this primal fear and humanity's shared experience of profound vulnerability. This highlights Munch's pioneering role in expressing subjective, internal experience on a grand scale, pushing the boundaries of psychological realism in art. This profound exploration of inner turmoil is a hallmark of modern art's shift towards psychological realism. It's a face you don't easily forget, a stark representation of humanity confronting its deepest fears.

The Precursor to Modern Abstraction: A Bridge to Inner Worlds

The Scream's radical departure from naturalistic representation and its intense focus on subjective experience laid crucial groundwork for the development of modern abstract art. For me, this is where Munch truly shines as a visionary, actively dismantling the long-held conventions of visual accuracy. By allowing emotion and internal states to dictate form and color, Munch pioneered a path that would be further explored by artists moving towards non-representational imagery, breaking new ground in artistic expression. The swirling lines and non-naturalistic palette anticipate the gestural abstraction and raw emotional intensity found in movements decades later, such as Abstract Expressionism. Think of Willem de Kooning's agitated brushstrokes, or Jackson Pollock's drips and splatters – you can almost see the lineage, the shared commitment to channeling internal states directly onto the canvas. While not purely abstract itself, The Scream liberates art from the constraints of objective reality, demonstrating that art's primary purpose can be to communicate profound, inner truths rather than merely to depict the visible world. This, in my opinion, makes it an indispensable work in the definitive guide to the history of abstract art.

The Turbulent Landscape: Nature's Unsettling Cry and the Oslofjord's Active Role

For me, the landscape in The Scream is far from a mere backdrop; it functions as an equally vital extension, almost a mirror, of the central figure's psychological state. The blood-red, swirling sky dominates the upper half of the composition – a violent, fiery vortex that uncannily mirrors the tumultuous inner world of the anguished figure. This isn't a picturesque sunset but an apocalyptic vision, undeniably reminiscent of a sunset over the Oslofjord from Ekeberg Hill, yet intensified far beyond naturalistic depiction to evoke a raw sense of dread and impending catastrophe. I find the theory that the intense, blood-red skies depicted could be influenced by the actual atmospheric phenomena witnessed across Europe after the 1883 eruption of the Krakatoa volcano incredibly compelling. This catastrophic volcanic event created vividly colored sunsets for years, and Munch, a keen observer of his environment and internal states, may have subconsciously or consciously integrated these spectacular, unsettling natural displays into his emotional landscape. Below this tempestuous sky, the dark, undulating lines of the fjord and land offer no solace; they echo the sky's distortion, creating a palpable sense of instability and a world that appears to teeter on the brink of collapse. It is as if nature itself is screaming, contorting in a symphony of distress, an environmental reflection of the internal torment, and perhaps, a haunting premonition of broader ecological anxieties, making it shockingly relevant to contemporary environmental discourse. The raw, primal quality of this landscape resonates with elemental fears, suggesting a world in distress that mirrors the human psyche. It’s a world crying out in unison with the figure, creating a powerful sense of cosmic empathy with the human condition. The winding, dark lines of the fjord and the vibrant, almost hallucinatory sky are deliberately distorted to reflect the internal turmoil of the figure. This isn't a serene Norwegian vista; it's a landscape infused with existential dread, where nature itself seems to participate in the cosmic scream. The familiar surroundings become alien and terrifying, emphasizing the figure's profound alienation not just from humanity, but from the very world around them. This personification of the landscape amplifies the sense of overwhelming forces acting upon the individual, effectively making the environment a mirror of the soul, transforming what would ordinarily be a beautiful view into a scene of apocalyptic anxiety. It’s as if the world is empathizing, or perhaps even generating, the central figure’s terror.

The Influence of Japanese Prints on Munch's Style: A Global Dialogue

While deeply personal, Munch’s style was also subtly, yet significantly, influenced by global art trends – something I find fascinating, as it shows how interconnected the art world truly is, often in unexpected ways. Notably, he was impacted by Japanese woodblock prints, or Ukiyo-e. The bold outlines, flattened perspectives, dynamic compositions, and emotional expressiveness found in works by artists like Katsushika Hokusai resonated deeply with Munch’s own developing aesthetic. You can see this influence in the stark graphic quality of his lithographs and woodcuts, including his print versions of The Scream, where forms are simplified, details are minimized, and lines carry immense expressive weight. Think of Hokusai's dramatic waves in The Great Wave off Kanagawa or his simplified figures in various landscape prints; there's a similar graphic power and directness in Munch's prints. It’s not about direct copying, of course, but about a shared sensibility towards graphic impact, expressive lines, and the ability to convey profound emotion through simplified forms. The dramatic compositions and subjective interpretations of nature prevalent in Japanese art provided a refreshing alternative to rigid Western academic traditions, empowering Munch to forge a new visual language that could articulate the raw intensity of human emotion without the need for literal realism. This cross-cultural exchange highlights the interconnectedness of global artistic developments during the late 19th century, proving that true artistic innovation often transcends geographical boundaries and draws strength from diverse sources.

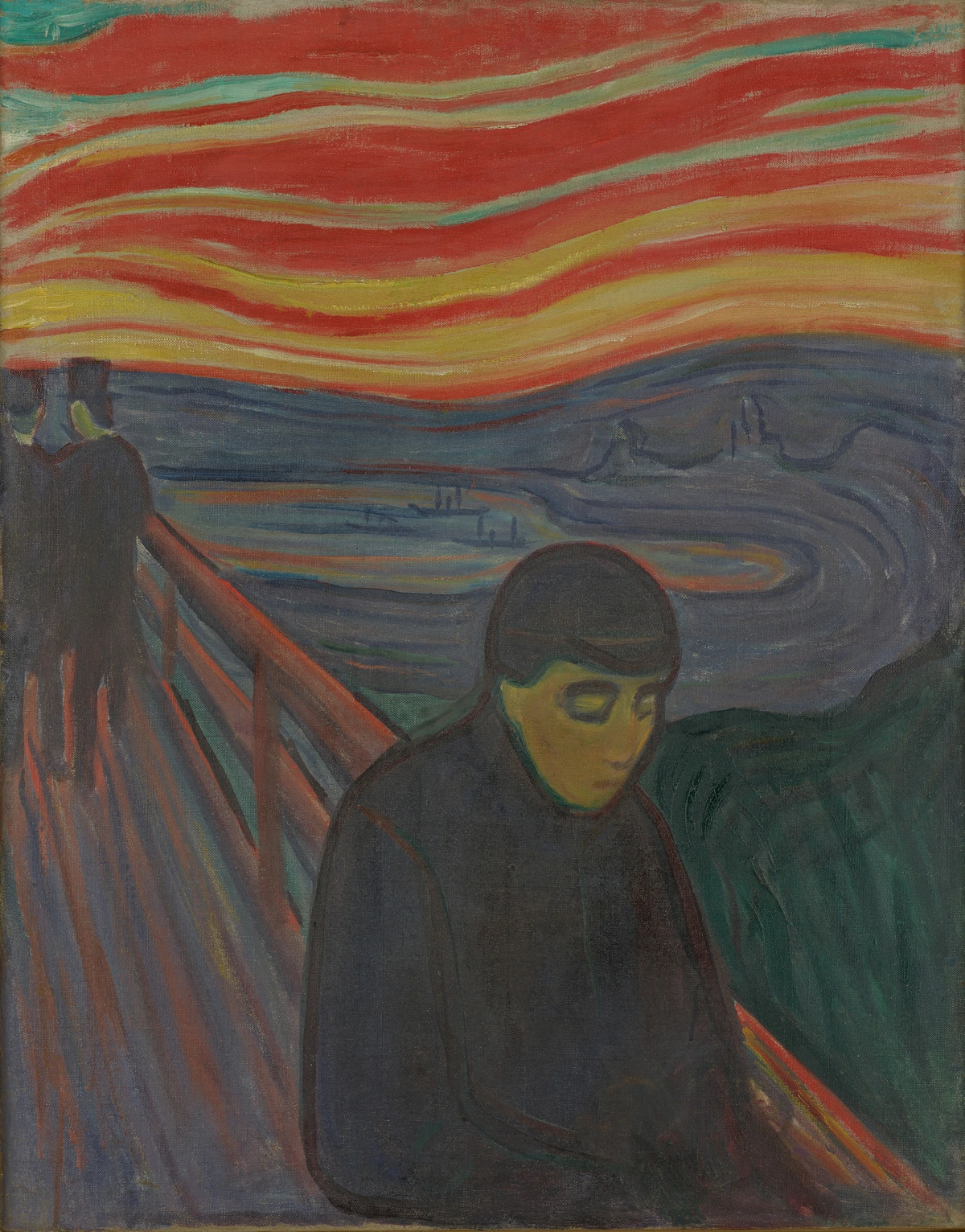

The Bridge and Distant Figures: Symbols of Isolation and Indifference in Modern Life

The bridge, typically a symbol of connection, transition, or safe passage, is here transformed into a desolate, almost menacing, diagonal thrust that plunges into the chaotic scene. Its stark, linear form contrasts sharply with the organic turbulence surrounding the central figure, yet it too contributes to the overwhelming sense of unease. This structural element, rigid yet unsettling, anchors the distorted landscape, pulling the viewer's eye into the depth of the scene and towards the central figure's anguish. It feels like a precipice of despair, a pathway to nowhere that emphasizes the figure's entrapment and profound disconnect from the world.

The presence of two distant, silhouetted figures walking calmly away in the background is profoundly significant. These figures are widely interpreted as Munch's friends, who, as he recounted, continued their walk seemingly oblivious to his profound moment of existential dread. Their depiction as unaware of the central figure's visible anguish powerfully reinforces themes of profound isolation and alienation in the burgeoning anonymity of modern urban life. This stark indifference underscores the intensely personal nature of the torment, suggesting that inner suffering can often go unseen or unacknowledged by the outside world, making the central figure's plight even more poignant and universally resonant. The juxtaposition of the screaming figure and the indifferent passersby highlights a crucial, often painful, aspect of the human condition: profound internal struggle can exist unseen amidst everyday life, a lonely cry in a busy world, a silent tragedy unfolding within a bustling world. It’s a chilling reminder that our deepest fears are often ours alone to bear, a poignant commentary on urban existence and the often-overlooked struggles of others, an almost prescient observation of the societal fragmentation to come.

The Paradox of the Silent Scream: More Terrifying Unheard and Universally Felt

One of the most profound paradoxes, and frankly, a stroke of genius in The Scream, is that the central figure is not screaming itself, but rather responding to a scream passing through nature. This "silent scream" is a powerful artistic device that heightens the sense of internal anguish and cosmic dread far more than a literal depiction ever could. The figure's hands pressed firmly to its ears suggest a desperate, futile attempt to block out an overwhelming, perhaps internal, sound. This absence of an actual vocalization, yet the powerful visual depiction of overwhelming sound, creates a unique tension, a psychological echo chamber. It transforms the artwork from a mere depiction of a person in distress into a universal symbol of the ineffable, unspoken fears that resonate deep within the human condition. I find that the silence of the scream makes it all the more deafening, inviting viewers to project their own anxieties onto the figure and experience the profound solitude of its torment. It's a scream that echoes in your own mind, a philosophical void that draws you in rather than pushes you away, reflecting perhaps the terrifying indifference of the cosmos and humanity's fragile place within it.

Color and Line: Expressionist Techniques for Emotional Impact

Munch's masterful employment of vibrant, often clashing colors and incredibly fluid, agitated lines is a defining characteristic of early Expressionism. Rather than aiming for realistic depiction – which, let's be honest, would fundamentally miss the artwork's emotional core – colors are employed with clear psychological intent, designed to express intense, raw emotion. The fiery reds and oranges of the sky don't merely depict a sunset; they convey alarm, passion, and an almost apocalyptic dread, a cosmic conflagration. Conversely, the somber blues and deep blacks of the fjord and figures evoke profound melancholy and despair, the weight of the void. Sickly yellows and greens suggest disease and a deep, unsettling unease, contributing to an overall sense of pervasive dread, a subtle, nauseating discord. This deliberate, non-naturalistic palette creates a visceral impact on the viewer, a hallmark of how artists use color to transcend mere representation, making The Scream a profound study in the psychology of color in abstract art. Furthermore, Munch's energetic, almost violent brushstrokes, particularly visible in the swirling sky and water, add a tactile dimension to the anguish, imbuing the surface of the painting with a restless, trembling texture that mirrors the internal state of the screaming figure. It's almost as if the canvas itself is trembling with the same anxiety.

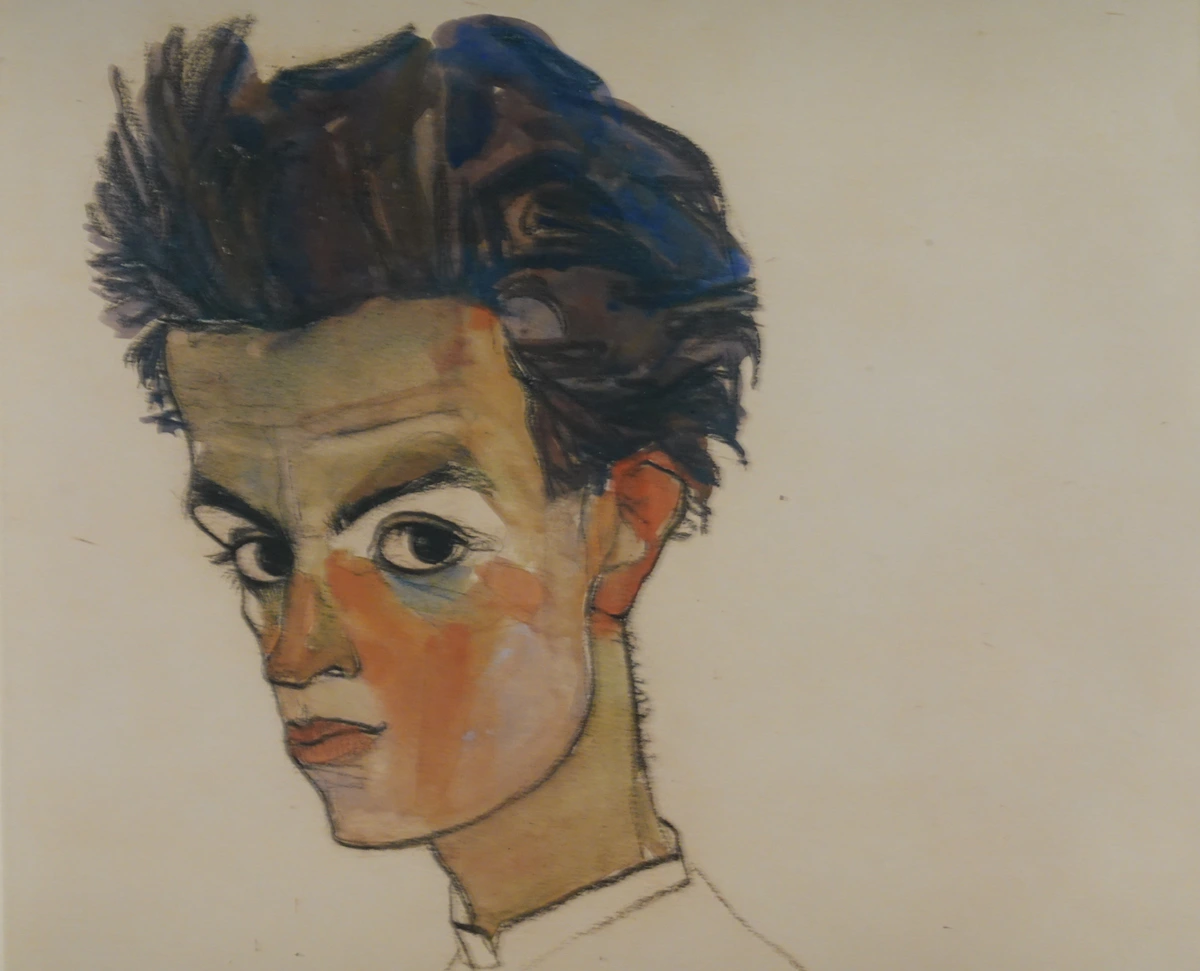

Understanding fundamental principles of how artists use color and the psychology of color in abstract art is, I believe, essential to fully grasp Munch's deliberate choices and their profound impact. Beyond color, the swirling, wavy lines that animate the sky, the water, and even the figure itself create a palpable sense of movement and psychological disturbance, making the entire composition vibrate with energy and anguish. This complete absence of calm, achieved through visual dynamism, immerses the viewer completely in the figure's turmoil. This radical approach profoundly influenced subsequent artists within the Expressionist movement, who, undeniably following Munch's pioneering lead, sought to convey intense inner experience over objective reality, often utilizing color and line in equally unconventional and emotionally charged ways. Artists like Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Franz Marc, and Egon Schiele, for instance, all adopted similar techniques to convey profound emotional and psychological states. The overall structure and interaction of these elements also exemplify sophisticated principles found in understanding the elements of design in art. It’s a masterclass in controlled chaos, a symphony of suffering rendered visible.

Munch's Innovative Use of Mediums: Beyond Painting to Printmaking

Munch's experimentation extended beyond his thematic concerns to his diverse use of artistic mediums – something I find truly innovative and visionary about his practice. While The Scream is primarily known through its painted and pastel versions, his creation of a lithographic stone was, as I mentioned earlier, equally revolutionary for its time, and a testament to his understanding of art's evolving role. This allowed for the widespread dissemination of the image, transforming it from a singular art object into a reproducible icon accessible to a broader, more democratic audience, almost foreshadowing the age of mass media. His work with woodcuts further demonstrates his innovative spirit, pushing the boundaries of printmaking to achieve raw, expressive effects that mirrored the emotional intensity of his paintings. For example, woodcuts allowed for a stark, almost brutal graphic quality that could strip the image down to its emotional essentials, enhancing its primal impact. Lithography, meanwhile, offered a fluidity of line and tonal range that could capture the psychological nuances of the painted versions in a reproducible format. This versatility across mediums underscores Munch's relentless pursuit of the most effective way to communicate his profound inner experiences, demonstrating that the 'scream' could manifest powerfully in various visual languages, each with its own unique emotional resonance. He wasn't confined by the canvas; he pushed every boundary he could, exploring how the texture of a woodcut or the immediacy of a lithograph could add new layers to his recurring themes of anxiety and isolation, ensuring his message reached as wide an audience as possible.

Key Expressionist Techniques in The Scream

Technique | Description | Impact in The Scream |

|---|---|---|

| Distortion | Deliberately altering natural forms to reflect subjective experience. | Figure's elongated body, skull-like face; warped landscape for psychological effect. |

| Exaggeration | Overstating features or colors to intensify emotional response. | Blood-red sky, intense undulating lines amplify dread and anxiety to an apocalyptic scale. |

| Non-Naturalistic Color | Employing color for its emotional and symbolic resonance, rather than literal realism. | Fiery oranges/reds for panic, sickly yellows for unease, deep blues for despair, creating a visceral psychological landscape. |

| Agitated Line | Dynamic, swirling, or jagged lines used to convey movement and inner turmoil. | Imparts a sense of restless movement, vibration, and profound psychological disturbance throughout the canvas, making the very air tremble. |

| Simplified Forms | Reducing details to essentials, focusing on the core emotional message. | Focuses attention on raw emotional content, stripping away specifics to make the figure universally relatable as an 'everyperson' in anguish. |

Color Symbolism in The Scream: A Symphony of Suffering and Psychological Depth

Munch’s color choices are, in my view, meticulously crafted to elicit a very specific emotional response from the viewer. They transcend mere visual representation to achieve a profound psychological resonance, directly tapping into our innate reactions to color. The artwork stands as a masterclass in how an artist can use color to communicate directly with the viewer's emotional landscape, creating a visceral, almost synesthetic, experience. For those interested in understanding the symbolism of colors in different cultures, The Scream offers a compelling example of universal color impact within a specific cultural context, despite its intensely personal origins. The following table details the dominant colors and their associated meanings and visual impact – it’s a terrifyingly beautiful symphony of suffering, an orchestrated assault on the senses designed to evoke maximum angst:

Color (Dominant) | Associated Emotion/Meaning | Visual Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Red/Orange | Anxiety, passion, fear, apocalypse, suffering, danger | Fiery, turbulent sky; intense and overwhelming, a literal scream of color, signaling cosmic dread and impending catastrophe. |

| Blue/Black | Melancholy, despair, isolation, death, grief, emptiness | Dark fjord, ominous shadows; weighty and sorrowful, almost suffocating, representing the void of existence and profound loneliness. |

| Yellow/Green | Sickness, unease, decay, jealousy, psychological distress, corruption | Pallid tones on figure; unsettling and sickly, contributing to the sense of dread and internal malaise, hinting at a diseased inner state. |

| White/Grey | Absence, ghostly, starkness, void, fragility, emptiness, pallor | Used sparingly for highlights, especially on the figure; enhances starkness and the figure's spectral, vulnerable quality, emphasizing its transient nature. |

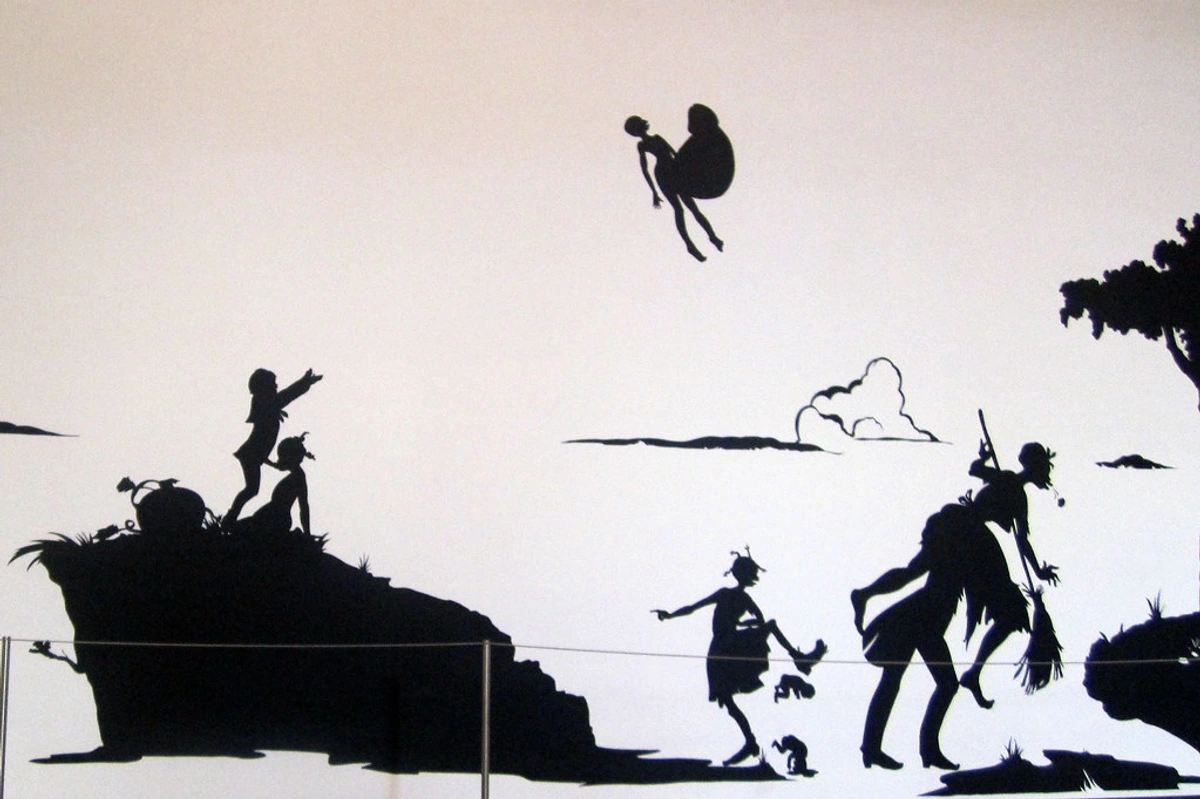

Symbolism: The Realm of the Inner World and its Literary Soulmates

Emerging in the late 19th century, Symbolism constituted a direct artistic rebellion against the perceived dryness of Realism and Naturalism, seeking to inject art with greater spiritual and emotional depth. This movement sought to express emotional experiences and abstract ideas indirectly, through evocative symbols, metaphors, and suggestions rather than direct, objective representation. Munch's work, particularly The Scream, is profoundly rooted in this tradition. The distorted figure, the turbulent landscape, and the unsettling color palette all function as potent symbols of deeper psychological states and universal existential feelings, transcending their literal forms to hint at an underlying, often disturbing, reality. The painting operates as a visual poem, an allegory about the human condition, inviting viewers to interpret its deeper emotional and philosophical resonances, hinting at a spiritual reality beyond the visible world. This emphasis on subjective interpretation marked a crucial departure from earlier art movements, a shift that continues to resonate today, as seen in understanding symbolism in contemporary art. It aligns beautifully with literary figures like Charles Baudelaire, whose decadent poetry explored urban alienation and the darker aspects of human nature; Stéphane Mallarmé, with his focus on the suggestive power of language and elusive meaning; and Edgar Allan Poe, a master of psychological horror and atmospheric dread, all of whom similarly explored the symbolic power of imagery and language to evoke mood and inner states, laying the groundwork for a more introspective art and allowing for a richer, multi-layered interpretation of reality. It's about what's felt, not just what's seen or described literally.

Expressionism: The Roar of the Inner Self and its Legacy

Beyond Symbolism, The Scream is, without a doubt, a foundational and quintessential work of Expressionism. This radical movement, which truly exploded primarily in Germany and Austria in the early 20th century, vehemently prioritized the artist's subjective internal experience and emotional response over objective reality or even conventional aesthetic beauty. Expressionism can be understood as art finding its roar, a powerful outpouring of inner states, a direct confrontation with the anxieties and truths of modernity. Expressionist artists, undeniably following Munch's pioneering lead, deliberately distorted reality, employed vivid and often unnatural colors, and utilized strong, almost aggressive lines to convey intense feelings, psychological truths, and sometimes biting social commentary. The Scream perfectly encapsulates this ethos, translating profound anxiety directly onto the canvas with an unprecedented rawness that continues to resonate today, making it a critical bridge in the definitive guide to the history of abstract art and a powerful precursor to subsequent movements like Abstract Expressionism. It's where art really started to get loud about feelings.

Key Expressionist groups, such as Die Brücke (The Bridge) and Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider), emerged, pushing these ideas even further. Die Brücke artists like Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, and Erich Heckel explored raw emotion through distorted figures, bold outlines, and intense, often jarring colors, seeking to break free from academic traditions and express the angst of modern urban life. They were painting the raw nerves of the city. Meanwhile, Der Blaue Reiter artists such as Franz Marc and Wassily Kandinsky explored the spiritual and abstract potential of art, moving towards non-representational forms to convey inner truths and a more utopian vision. Egon Schiele, with his agonizing, introspective self-portraits, similarly expanded upon this tradition, pushing the boundaries of depicting human emotion and the inner landscape with stark, almost brutal honesty. The profound impact of The Scream extends even to movements like Neo-Expressionism much later in the 20th century, demonstrating Munch's enduring spirit and its lasting influence on art that seeks to express profound inner states. Munch's work, therefore, serves as a crucial foundational pillar for much of 20th-century art that valued subjective expression over objective representation. He really opened the floodgates for inner worlds on canvas.

Munch's Broader Oeuvre: The Frieze of Life – A Poem of Existence

To fully appreciate The Scream, I think it's absolutely essential to understand its place within Edvard Munch's ambitious larger project, the "Frieze of Life: A Poem about Life, Love, and Death." Conceived as a grand pictorial cycle exploring the fundamental themes of existence – birth, love, sickness, anxiety, and death – this monumental series occupied much of Munch's creative energy between the 1890s and the early 1900s. The Scream is not an isolated work but rather a powerful, distilled expression of the existential anguish that permeated this entire series, a central pillar in his lifelong exploration of human psychological states.

Other significant works within the Frieze include "Love and Pain (Vampire)," which, with its haunting, almost predatory embrace, explores the destructive and consuming aspects of love and desire; "Madonna," a complex and provocative portrayal of female sexuality and fertility intertwined with intimations of death and religious ecstasy; "Anxiety," depicting a crowd consumed by collective dread on a bridge strikingly similar to that in The Scream, highlighting a shared societal unease; and "Melancholy," a deeply personal reflection on grief and isolation often featuring a brooding figure by a shore, capturing the quiet despair that permeated his life. All of these works delve into the darker psychological landscapes of human experience, creating a cohesive visual narrative that speaks to universal human struggles. This broader context reveals Munch's profound dedication to creating a visual narrative of modern human consciousness, where The Scream serves as a piercing, unforgettable climax of emotional despair. The Frieze aimed to be a "poem of life, love and death," and The Scream stands as its most iconic and unsettling verse, offering a profound insight into the cyclical nature of human emotion as perceived by Munch. Munch's exploration of these universal human dramas established him as a master of psychological portraiture, not just of individuals, but of the collective human soul, laying bare the vulnerabilities and triumphs of existence. It's a testament to his unflinching gaze into the human condition.

Multiple Versions: A Recurring Vision, A Deepening Obsession

Edvard Munch, driven by what appears to be an almost compulsive need, created The Scream in several iterations. This practice isn't merely an artistic choice; it's a testament, I think, to the powerful, persistent, and haunting nature of his vision, suggesting an artist grappling deeply with a profound, overwhelming emotion that required multiple attempts to fully articulate. The act of returning to the same motif allowed him to explore every nuance of his traumatic experience, to refine its emotional impact, and to experiment with different mediums to amplify its message, showcasing his mastery of various artistic techniques. In total, there are four primary versions of The Scream: two painted versions, two pastel versions, and a lithographic stone from which numerous prints were made, each offering a slightly different interpretation of the core, agonizing theme and showcasing variations in technique and emotional register. It’s as if he couldn’t let the scream go, constantly trying to perfect its visual articulation. This iterative process highlights his relentless pursuit of emotional truth and his belief that a single artwork could never fully encapsulate the depth of his internal world.

Version Type | Year(s) | Medium | Location | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Painting | 1893 | Oil, tempera, pastel on cardboard | National Gallery, Oslo | Often considered the first, with a more muted, somewhat somber palette that emphasizes the internal dread. |

| Pastel | 1893 | Pastel on cardboard | Munch Museum, Oslo | Very similar to the 1893 painting, but with a vibrant, almost hallucinatory intensity of colors. |

| Pastel | 1895 | Pastel on cardboard | Private Collection (Sotheby's sale 2012) | This is perhaps the most vibrant and dynamically colored of the pastel versions, famously sold for nearly $120 million to American financier Leon Black. It even bears a disturbing inscription, likely by Munch himself, "Could only have been painted by a madman!" |

| Painting | 1910 | Tempera on cardboard | Munch Museum, Oslo | A later, somewhat more robust version; often considered the most 'finished' painted version in terms of execution, with clearer forms. |

| Lithograph | 1895 | Lithographic stone/print | Various collections, including Munch Museum | This black and white version strips the image down to its rawest graphic lines, emphasizing form and stark contrast, making the anguish feel almost primal. |

The existence of multiple versions of The Scream truly underscores Munch's relentless, almost obsessive, exploration of his traumatic experience. It is a testament to his dedication to distilling its essence into a universally understood visual language. Each iteration refines and re-emphasizes those core, haunting themes of anxiety and existential dread, showcasing Munch's profound engagement with the subject matter. For instance, the 1893 painting is often noted for its muted, almost somber tones, while the 1895 pastel version, famously sold for nearly $120 million to American financier Leon Black, bursts with an almost hallucinatory vibrancy, highlighting the different emotional registers Munch could achieve through subtle shifts in medium and palette. This 1895 pastel even bears a disturbing inscription, likely by Munch himself, "Could only have been painted by a madman!", underscoring the intense personal connection and psychological turmoil inherent in its creation. This inscription is often interpreted as both a defiant response to critics who questioned his sanity and a raw, candid acknowledgment of his own profound psychological struggles – a window into his tormented soul. The lithograph, being black and white, strips the image down to its rawest graphic lines, emphasizing form and stark contrast, thereby making the anguish feel even more primal and universally graphic. This methodical, almost ritualistic re-engagement with the subject speaks to an artist grappling deeply, perhaps desperately, with an overwhelming personal and universal emotion that he felt compelled to capture in every facet. This intense artistic process exemplifies a profound dedication to conveying inner experience, showing how different materials—from the layered textures of oil and tempera to the vibrant immediacy of pastel and the stark clarity of lithography—could each contribute uniquely to the artwork's emotional texture. This constant re-visitation of the theme highlights its central importance within Munch's entire artistic output and his persistent quest to encapsulate fundamental human experiences. It’s an artist haunted, and in turn, haunting us.

This array of versions demonstrates Munch's enduring fascination with the subject, treating it as an evolving psychological landscape rather than a single, fixed image. Each iteration, while similar, offers nuanced insights into the artist's persistent exploration of this profound, singular moment of terror and spiritual insight.

The Thefts of The Scream: Art in Peril and Enduring Public Fascination

Further adding to the dramatic legacy of The Scream are the high-profile thefts of two of its versions. These incidents, I find, underscore not only the immense cultural and monetary value of the artwork but also its enduring power to capture public imagination, even in its absence. These events transformed The Scream into a symbol of both artistic vulnerability and the global appetite for masterpieces, often elevating its mystique. The narrative of peril and recovery only reinforces its mythic status as a fragile yet powerful symbol of human vulnerability, making it an artwork that has literally been fought over.

The 1994 Theft: A Daring Olympic Heist

In a brazen act of art theft, the 1893 painting from the National Gallery, Oslo, was stolen on February 12, 1994 – the opening day of the Winter Olympics in Lillehammer. The sheer audacity! The thieves even left a note reading, "Thanks for the poor security." This audacious crime, executed in just 50 seconds, sent shockwaves through the art world and captured international headlines. The painting was recovered a few months later, on May 7, 1994, largely intact, after a carefully orchestrated sting operation. The rapid recovery highlighted the immense pressure and global efforts to retrieve such an irreplaceable cultural artifact. It was a moment of collective sigh of relief for the art world.

The 2004 Theft: A Daylight Robbery and Damaged Recovery

A decade later, in a similarly audacious daylight robbery on August 22, 2004, the 1910 painted version of The Scream and Munch's Madonna were stolen from the Munch Museum in Oslo. Masked gunmen entered the museum, ripped the artworks from the walls, and escaped in a waiting car. This theft sparked widespread condemnation and fears that the fragile artworks might be permanently lost or damaged. Both works were eventually recovered in a police operation in 2006, though with some damage, including moisture damage and scratches, which necessitated extensive restoration work. These incidents underscore not only the immense cultural and monetary value of The Scream but also its enduring power to capture public imagination, even in its absence. The drama surrounding its thefts only reinforces its mythic status as a fragile yet powerful symbol of human vulnerability and resilience. It's a testament to its irresistible pull, even for criminals.

The Context of Modernism: A New Artistic Paradigm and its Avant-Garde

I often think about how The Scream didn't just appear in isolation; it was a clear product of a seismic shift in Western art, moving away from the staid academic traditions of the past and hurtling towards the radical experimentation of Modernism. This era, roughly from the late 19th to the mid-20th century, was characterized by artists actively challenging established norms of representation, form, and even what was considered a legitimate subject matter. Movements like Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, and Cubism were all contributing to this departure from literal depiction, pushing art into new territories, away from the literal and towards the felt. Munch, while undeniably distinct in his intensely personal focus, contributed significantly to this broader narrative by honing in on the psychological and emotional landscape, rather than merely external appearances. His work profoundly influenced subsequent generations, inspiring artists to use their craft as a raw means of personal expression and even social critique, thereby setting the stage for much of the 20th century's artistic innovation. This cemented his place among the most important artists of the era. The radical approach to composition and narrative also ties beautifully into broader discussions on visual storytelling techniques in narrative art and the entire history of abstract art, highlighting its foundational role in artistic evolution, and influencing everything from Surrealism's exploration of the subconscious to Abstract Expressionism's raw emotional outpouring. Munch's contribution was to lay bare the inner turmoil, making the unseen visible and deeply felt. He truly helped unlock the modern psyche on canvas, preparing the ground for further radical experimentation in art.

The Universal Echo: Why The Scream Resonates So Deeply Across Generations

The Scream's profound and enduring resonance across cultures and generations lies, for me, in its unparalleled ability to tap into fundamental, universal human emotions. It articulates a primal sense of profound anxiety, alienation, and existential dread that remains chillingly timeless. In an increasingly complex, interconnected, yet often overwhelming world, this image speaks powerfully to those moments when individuals feel utterly overwhelmed, unheard, or profoundly isolated within the vastness of existence. It captures the very essence of the modern condition of spiritual anguish, the deep fear of losing oneself, and the silent cries of individual suffering amidst collective indifference. Philosophically, it touches upon themes of nihilism and the inherent meaninglessness some perceive in the universe, making the figure's response a visceral, almost primal, reaction to an indifferent cosmos.

The Universal Echo: Why The Scream Resonates So Deeply Across Generations

The Scream's profound and enduring resonance across cultures and generations lies, for me, in its unparalleled ability to tap into fundamental, universal human emotions. It articulates a primal sense of profound anxiety, alienation, and existential dread that remains chillingly timeless. In an increasingly complex, interconnected, yet often overwhelming world, this image speaks powerfully to those moments when individuals feel utterly overwhelmed, unheard, or profoundly isolated within the vastness of existence. It captures the very essence of the modern condition of spiritual anguish, the deep fear of losing oneself, and the silent cries of individual suffering amidst collective indifference. Philosophically, it touches upon themes of nihilism and the inherent meaninglessness some perceive in the universe, making the figure's response a visceral, almost primal, reaction to an indifferent cosmos. It's a scream that transcends language.

Its pervasive popularity in popular culture, manifesting in countless parodies, memes, and even emojis, further attests to its iconic status and its uncanny ability to represent a shared human experience of distress. This widespread adaptation demonstrates how the image has transcended its original artistic context to become a universal shorthand for feelings of angst, shock, and alarm in contemporary society, appearing in everything from animated TV shows like The Simpsons to horror movie posters, and even in contemporary political cartoons. Like Picasso's monumental anti-war statement, Guernica, The Scream functions as a powerful cultural touchstone for human suffering, a visual language understood across linguistic and cultural barriers. It stands as a profound testament to the power of art to both reflect and shape our collective consciousness, providing a visual lexicon for humanity's deepest fears and anxieties. This cultural ubiquity ensures its legacy will continue to evolve and resonate for generations to come. It’s a silent cry, but one that everyone understands, a truly global symbol of the human condition.

Legacy and Enduring Relevance: The Scream in Perpetuity

Legacy and Enduring Relevance: The Scream in Perpetuity

Edvard Munch's The Scream irrevocably cemented his place as a true pioneer of modern art and an indisputable key figure in the development of Expressionism. Its profound influence reverberates through the psychological depth evident in subsequent artists, notably in the raw emotionality found in works by Francis Bacon, who continued to explore themes of visceral human experience and psychological torment. Or think of the elongated, existential portraits of artists like Alberto Giacometti. Beyond Bacon, Munch's impact can be seen in the broader artistic shift toward exploring complex inner landscapes, affecting movements such as Abstract Expressionism, where artists like Willem de Kooning channeled raw emotion into agitated, distorted forms. The artwork astonishingly continues to possess startling relevance today, acting as a potent touchstone in contemporary conversations surrounding mental health, human vulnerability, and the existential and environmental anxieties that characterize the modern world. It remains a powerful, almost prophetic, reminder of art's unparalleled capacity to give vivid form to humanity's deepest fears, anxieties, and most inchoate emotions, thereby offering a means of processing and understanding them. Its radical departure from traditional aesthetics also laid groundwork for later movements, demonstrating its crucial place in the history of abstract art and its profound impact on subsequent art as a catalyst for social change. The power of The Scream lies not just in its historical impact, but in its continuous ability to resonate with each new generation, reflecting evolving societal anxieties and personal struggles. It just keeps screaming.

For those seeking to appreciate the raw power of such works, visiting a museum like the Den Bosch Museum is highly recommended, or perhaps exploring contemporary art that channels similar emotional intensity. Art lovers may even find a piece to buy that speaks to their own inner landscape, resonating with the enduring echo of Munch's masterful work. The ongoing dialogue between The Scream and contemporary society ensures its position not merely as a historical artifact, but as a living, breathing commentary on the perennial human condition. Its message is as potent and relevant today as it was over a century ago.

Conclusion: The Ever-Echoing Cry and Its Timeless Power

Edvard Munch's The Scream is, for me, far more than just a celebrated painting; it is a profound cultural artifact, a truly timeless articulation of universal human anguish. From its deeply personal genesis in Munch's own suffering and the collective anxieties of the Fin de Siècle, to its enduring influence on modern art and its pervasive, almost inescapable, presence in popular culture, this artwork speaks to an essential, often uncomfortable, truth about the human condition: humanity's capacity for overwhelming despair. Its distorted forms, searing colors, and utterly solitary figure continue to resonate because they give powerful voice to the unspoken fears and isolations that persist across generations. It stands as a primal scream that never fades, a testament to the fact that some emotions are so fundamental they transcend eras. As a mirror to the collective soul, The Scream remains an eternal testament to art's unparalleled power to confront, express, and ultimately help us understand the deepest, most vulnerable facets of emotional existence. It is a dialogue that continues to unfold between the artwork and its viewers, and within humanity itself, cementing its status as an indispensable guide to the profound depths of human experience. It is a masterpiece that will continue to echo through time, prompting introspection and a deeper understanding of the human condition, a reminder that some screams are meant to be heard across the ages, a true landmark in the timeline of human expression.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What is the story behind The Scream?

The Scream was directly inspired by a deeply personal and profound moment experienced by Edvard Munch. In a diary entry from January 22, 1892 (though some art historians cite 1893 as the year of initial conception), he recounted walking with friends at sunset when the sky turned a "blood red," causing him to pause, feeling exhausted and "trembling with angst." He then "sensed an infinite scream passing through nature," an overwhelming emotional and sensory experience that translated into the iconic imagery of the artwork. It is a visual representation of a profound existential crisis felt by the artist, which he then universalized, making it a powerful symbol of modern anxiety and human vulnerability.

When was The Scream created?

The initial conception for The Scream occurred in 1892, as inspired by Munch's famous diary entry about sensing an "infinite scream passing through nature." The first painted version was completed in 1893. Munch then created several other versions, including pastels and a lithograph, up to 1910, continually revisiting this powerful motif to explore its nuances.

What is the setting of The Scream?

The setting for The Scream is Ekeberg Hill, overlooking the Oslofjord and the city of Oslo, Norway. This specific location was where Edvard Munch experienced the profound, synesthetic moment that inspired the artwork, as he described the sky turning blood-red and feeling an "infinite scream passing through nature." The bridge depicted in the foreground is also believed to be a real bridge in that area, adding a layer of grounded reality to the intensely subjective experience. This specific geographical backdrop adds a unique resonance to the artwork, intertwining personal anguish with a familiar landscape.

What artistic movement is The Scream associated with?

The Scream is primarily associated with Expressionism, a revolutionary art movement that prioritized the artist's subjective emotional experience over objective reality. It is also deeply rooted in Symbolism, which sought to express abstract ideas and emotions through powerful symbolic forms. Art historians widely consider it a foundational work of Modernism due to its radical approach to depicting elusive inner states. It stands as a crucial crossroads of artistic thought, bridging late 19th-century symbolic approaches with early 20th-century expressive intensity, and influencing subsequent movements like Abstract Expressionism and Neo-Expressionism.

What does The Scream symbolize?

The Scream profoundly symbolizes universal human anxiety, existential dread, alienation, and an overwhelming feeling of inner torment or spiritual anguish. Crucially, the central figure is not depicted as making the sound; rather, it represents a primal cry in response to the perceived "scream" of nature or existence itself – a feeling that envelops the individual. This conveys a profound sense of external forces acting upon an isolated psyche, highlighting themes of human vulnerability and the pervasive anxieties of the modern condition.

What does the inscription 'Could only have been painted by a madman!' mean?

One of the pastel versions of The Scream, specifically the 1895 version, bears a faint inscription: "Could only have been painted by a madman!" This inscription, believed to have been added by Munch himself, has been a subject of much speculation. It is generally interpreted as either a defensive response to public criticism of his mental state and his art, or as a deeply personal, raw acknowledgement of his own psychological struggles and the intense inner turmoil that fueled his creative process. It highlights the profound connection between Munch's mental health and his artistic output, making the artwork an even more poignant reflection of his inner world and the societal perceptions of artistic genius versus madness.

Who owns the most famous version of The Scream?

One of the pastel versions of The Scream, specifically the incredibly vibrant 1895 version, was famously sold at Sotheby's in 2012 for nearly $120 million (approximately £74 million at the time). Owned by Norwegian businessman Petter Olsen, its buyer was later revealed to be American financier Leon Black. This version is now held in a private collection, making it one of the most valuable artworks ever sold at auction and a significant moment in the art market, underscoring its immense cultural and monetary value as a global icon.

How many versions of The Scream are there?

Edvard Munch created a total of four primary versions of The Scream: two painted versions (one from 1893 at the National Gallery, Oslo; another from 1910 at the Munch Museum, Oslo) and two pastel versions on cardboard (one from 1893 at the Munch Museum, Oslo; and one from 1895, famously sold at Sotheby's, now in a private collection). Additionally, he created a lithographic stone in 1895 from which numerous black and white prints were made, further disseminating the iconic image. Each version offers a slightly different nuance to the artwork's emotional intensity and technique.

What is the meaning of the two figures in the background?

The two distant, silhouetted figures on the bridge in The Scream are incredibly potent. They are typically interpreted as representing the artist's friends who, as Munch recounted, walked on ahead during his profound moment of anxiety and spiritual crisis. Symbolically, they emphasize the central figure's profound isolation and alienation, highlighting the excruciating reality of how personal suffering can be experienced in complete solitude, even when others are physically nearby. Their utterly detached presence underscores the intensely subjective and internal nature of the central figure's torment – a powerful visual metaphor for feeling utterly alone with one's pain amidst an indifferent world, and a comment on the disconnection inherent in modern urban life.

What materials did Edvard Munch use for The Scream?

Edvard Munch utilized various mediums across the different versions of The Scream. The two painted versions are primarily executed in oil, tempera, and pastel on cardboard. The two pastel versions are, as the name suggests, pastel on cardboard. Additionally, he created a lithographic stone in 1895 for the print versions, which allowed for wider dissemination of the image through black and white prints. This experimentation with different materials highlights his dedication to exploring the full emotional and graphic potential of his vision, showcasing his versatility and innovative approach to conveying intense psychological states.

Where is The Scream located?

For those eager to see one of these iconic works in person, two painted versions of The Scream are housed in Oslo, Norway: one at the National Gallery (the 1893 version) and another at the Munch Museum (the 1910 version). The 1893 pastel version is also housed at the Munch Museum. The most famous 1895 pastel version, having fetched nearly $120 million, remains in a private collection and is therefore not regularly accessible to the public. Experiencing any of the publicly displayed versions is a profound encounter with this masterpiece, offering a direct engagement with Munch's powerful vision and allowing for a deeper understanding of its nuances across different mediums. For those seeking to appreciate the raw power of such works, visiting a museum like the Den Bosch Museum is highly recommended, or perhaps exploring contemporary art that channels similar emotional intensity.

How does The Scream relate to mental health?

One of the most compelling aspects of The Scream is its profound connection to mental health. It is often seen as a powerful, almost prophetic, artistic representation of intense psychological distress, making it deeply relevant to contemporary discussions surrounding mental well-being. The figure's profound anguish, isolation, and overwhelming sense of dread resonate directly with experiences of anxiety, depression, and existential crisis. Edvard Munch himself battled significant mental health issues throughout his life, and the artwork can be viewed as a raw, honest, and courageous portrayal of inner torment, offering a visual language for experiences that are often incredibly difficult to articulate verbally. In this sense, it can foster a sense of shared human experience and understanding, breaking down stigma and providing a visual lexicon for complex emotional states.

What inspired The Scream?

As previously discussed in the article, The Scream was inspired by a deeply personal and what Munch called a "synesthetic" experience. This occurred during a sunset walk with friends in Oslo, specifically on Ekeberg Hill overlooking the city and the fjord. Munch famously described feeling an "infinite scream passing through nature" as the sky suddenly turned blood-red, inducing in him a profound sense of exhaustion and trembling anxiety. It was an intense moment of psychological breakthrough that translated directly into the iconic imagery of the artwork. This fusion of internal sensation and external perception is what makes the work so potent and universally resonant, offering a unique glimpse into the artist's psyche and his profound connection to the natural world.

What specific art techniques did Munch use in The Scream?

Munch's genius shines in the specific techniques employed in The Scream, which are hallmarks of both Expressionism and Symbolism. These techniques collectively create an utterly visceral and emotionally charged artwork that bypasses the intellect and directly impacts the viewer. Key techniques include:

- Distortion of Form: The central figure and the entire landscape are intentionally warped and elongated, not to depict objective reality, but to convey sheer emotional intensity and profound psychological distress, making the inner world visible.

- Expressive Color: Munch uses vibrant, often clashing, and decidedly non-naturalistic colors – such as fiery reds and oranges contrasted with somber blues – specifically to evoke intense emotions and create a tumultuous, almost apocalyptic atmosphere, rather than merely representing natural light.

- Agitated Lines: The swirling, wavy lines throughout the composition are deliberate, creating a palpable sense of movement, unease, and profound psychological disturbance, making the entire scene vibrate with anxiety and inner turmoil.

- Simplified Forms: Unnecessary details are minimized, focusing attention on the raw emotional impact of the primary elements, prioritizing universal feeling over fussy realism and specific narrative.

- Bold Outlines: Strong, dark outlines often define the forms, separating them from the swirling background and heightening their dramatic impact and legibility of anguish, almost like a graphic novel of despair.

Together, these techniques combine to create an utterly visceral and emotionally charged artwork that bypasses the intellect and goes straight to the viewer's emotional core, cementing The Scream's reputation as a masterpiece of emotional conveyance. It's an artwork that doesn't just show you suffering; it makes you feel it.

What were the contemporary reactions to The Scream?

Upon its first exhibition, The Scream evoked strong and often polarized reactions. While some critics were deeply moved by its raw emotional power, others found it disturbing, grotesque, or even evidence of the artist's supposed mental instability. It challenged conventional notions of beauty and artistic subject matter, prompting both fascination and repulsion. This mixed reception, however, only solidified its status as a revolutionary and controversial work that spoke directly to the anxieties of the emerging modern age, foreshadowing the seismic shifts in artistic taste and appreciation that would define the 20th century. Its reception highlighted the deep-seated societal discomfort with raw emotional expression in art.

What is the significance of The Scream today?

The significance of The Scream today is, for me, multifaceted and ever-evolving. It remains a potent symbol of universal human anxiety, alienation, and existential dread, resonating deeply in our complex modern world. The artwork continues to be a powerful touchstone in discussions about mental health, human vulnerability, and the existential and environmental anxieties that characterize contemporary society. Its iconic status has led to its pervasive presence in popular culture, from parodies to emojis, solidifying its role as a universal shorthand for distress. Ultimately, it stands as an enduring testament to art's capacity to articulate profound human emotion and stimulate introspection, serving as a timeless reminder of the shared human experience of angst and resilience. It's a dialogue that never ends.

How did The Scream influence other artists and movements?

The Scream's influence is vast and multifaceted. It served as a foundational work for Expressionism, inspiring artists to prioritize subjective emotional experience over objective reality. Its raw psychological depth resonated with later artists like Francis Bacon and even contributed to the development of Abstract Expressionism's focus on conveying inner states through gestural abstraction. Its iconic status has also led to its widespread appropriation in popular culture, cementing its role as a universal symbol of anxiety and distress across various media and generations. Munch's innovative use of color and line to express psychological states directly contributed to the broader modernist project of exploring the inner world, making it a touchstone for artists seeking to break free from traditional representation and delve into the complexities of human emotion. His work opened doors for subsequent generations to explore inner landscapes with unprecedented honesty and intensity.

The Scream's influence is vast and multifaceted. It served as a foundational work for Expressionism, inspiring artists to prioritize subjective emotional experience over objective reality. Its raw psychological depth resonated with later artists like Francis Bacon and even contributed to the development of Abstract Expressionism's focus on conveying inner states through gestural abstraction. Its iconic status has also led to its widespread appropriation in popular culture, cementing its role as a universal symbol of anxiety and distress across various media and generations.

Is The Scream a self-portrait?

Is The Scream a self-portrait?

While the figure in The Scream isn't a literal self-portrait in the traditional sense, many art historians and I believe it can be interpreted as a profound psychological self-portrait of Edvard Munch. The intense anguish and existential dread depicted directly reflect Munch's own struggles with mental health, personal tragedies, and profound anxieties throughout his life. The figure embodies the emotional state Munch experienced during his famous "scream passing through nature" moment, making it a visceral representation of his inner turmoil rather than merely his physical likeness. It's a depiction of his soul laid bare, a universalization of intensely personal suffering.

Is The Scream a real event or a metaphor?

The Scream is both a depiction of a real, deeply personal event experienced by Edvard Munch and a powerful metaphor for universal human anguish. Munch's diary entry describes a specific moment of profound emotional and sensory overwhelm. However, his artistic rendering transcends this literal event, transforming it into an archetypal symbol of existential dread, isolation, and the 'scream' of nature itself. It is a work where subjective reality and universal metaphor intertwine, making it resonate deeply with viewers across time and culture.