Käthe Kollwitz: Expressionism's Soul, Social Art & Enduring Empathy for Justice

Explore Käthe Kollwitz's profound German Expressionism, printmaking mastery, and powerful social art. Delve into her life, works, and lasting legacy as a voice for empathy, social justice, and human resilience.

Käthe Kollwitz: Expressionism's Deep Soul & Unflinching Social Art

You know, sometimes an artist’s soul doesn’t just speak its truth; it screams it, with every line and shadow. This raw, visceral expression is precisely what defines the art of Käthe Kollwitz, a name synonymous with profound emotional power and unwavering social conscience. Her creations aren't merely pictures; they're a visceral punch, a heartbreaking embrace, and a quiet, defiant protest all woven into one. They hit you right in the gut with raw emotion, refusing to let go, revealing what I call Expressionism’s Deep Soul. What do I mean by a "deep soul"? For me, it's that raw, authentic core of human experience – the profound empathy, the unvarnished grief, the quiet dignity in suffering – that Kollwitz masterfully brings forth, stripping away all pretense. It's the artistic embodiment of "inner necessity," a concept central to early Expressionists like Kandinsky, where art flows not from external observation but from an urgent, internal spiritual or emotional impulse. When I look at the raw, almost contorted composition of a piece like her "Woman with Dead Child", I instantly feel that intense, protective grief – it’s not an abstract concept; it’s rooted in the tangible, agonizing reality of loss that strikes you right to the core. And honestly? That’s exactly what art should do sometimes. It shouldn’t always be pretty or comfortable. It should make you feel, deeply and without compromise. For me, Kollwitz’s profound ability to convey such raw, internal emotional truth through depictions of human suffering is the very essence of this profound artistic spirit. It challenges me in my own work, reminding me that even amidst the vibrant colors of my contemporary art prints, the underlying intention to connect and evoke emotion is paramount.

The Crucible of Her Life: Forging a Vision from Upheaval

I find myself often thinking about the lives artists lead, the crucible of experiences that forge their unique vision. It’s almost impossible, I think, to separate Käthe Kollwitz’s art from her life, which, frankly, was a series of profound trials. Born in 1867 in Königsberg (now Kaliningrad), she was steeped in social consciousness from an early age. Her grandfather, a prominent socialist pastor, and her socialist father instilled in her a deep empathy for the working class and a commitment to social justice. They championed ideals of communal welfare, workers' rights, and a fierce opposition to militarism – principles that would become the very bedrock of Kollwitz's artistic philosophy. Can you imagine growing up in a household where social justice wasn't just a concept, but the very air you breathed? It shaped her fundamentally, pointing her compass towards humanity's struggles and the burgeoning socialist movements of the late 19th century, which sought radical reforms for the industrialized poor.

After studying in Berlin and Munich, honing her skills under influential tutors who recognized her nascent power, it was the gritty reality of life in working-class Berlin that truly cemented her artistic mission. Here, living with her doctor husband in an impoverished district, she bore witness daily to the harsh conditions of burgeoning industrialization – the cramped, often unsanitary Mietskasernen (tenement blocks) with their dark, disease-ridden courtyards where families were crammed into single rooms, the pervasive illness, the grueling labor, and the stark inequalities that defined late 19th and early 20th century Germany. This was a society grappling with rapid modernization, social unrest, and burgeoning social democratic movements that sought to address the very issues Kollwitz observed. She wasn't an outsider looking in; she was intimately connected to the suffering around her, breathing its dust and feeling its weight. The streets around her studio weren't just backdrops; they were a living, breathing testament to the struggles of the proletariat, echoing the cries of the 1848 revolutions and the burgeoning labor movements of the Wilhelminian Era. This era, marked by a rigid class structure and the burgeoning might of Prussian militarism, laid a volatile groundwork for the tragedies that would soon engulf Europe and shape Kollwitz's entire artistic output.

Living through such unimaginable upheaval – two world wars, profound poverty, and the agonizing personal loss of her own son, Peter, in World War I, and later her grandson to World War II – these weren't distant, philosophical themes for Kollwitz. They were her lived reality, soaking into every fiber of her being. The death of her beloved son, Peter, on the Belgian front in 1914, was not just a personal tragedy; it became a defining catalyst for her pacifist art. From that moment, her work deepened into a profound, universal lament against war's brutality, transforming her empathetic observation into an urgent, heart-wrenching plea for peace. You can almost trace the trajectory of her grief in her art, from the raw, immediate anguish of early pieces like "Mother with Dead Child" to the more universal, almost stoic sorrow of her later series, each a testament to a loss that never truly healed, but instead evolved into a sustained, defiant artistic statement. While some artists might engage with poverty or war as abstract subjects, Kollwitz experienced them in their most brutal, personal forms. This wasn't some distant observer making pretty pictures; this was a woman bleeding her experiences onto the page, using profound empathy and personal losses to fuel her art. It pushed her to use her platform for quiet but persistent activism, tirelessly advocating for peace and the rights of the working class. Her art was raw, unfiltered, and deeply empathetic. She looked at the working class, the bereaved mothers, the victims of war, and she saw herself, her family, her neighbors. It’s almost like she was asking, "How can I look away when this is the truth of our existence?" It’s a question I sometimes ask myself when I'm tempted to just make something 'nice' and comfortable, and I appreciate her honesty.

Carving Truth: The Unyielding Power of Her Lines and Printmaking

With such profound truths to convey, Kollwitz turned to mediums that could not only capture but amplify the raw realities of her subjects, leading us directly to her powerful work in printmaking. For Kollwitz, the medium wasn't just a tool; it was an integral part of the message, a silent megaphone for her profound social commentary. Think about it: these mediums lent themselves perfectly to her vision, allowing for stark contrasts, powerful, often unforgiving lines, and an unvarnished rawness that simply couldn't be achieved with softer, more 'decorative' forms. There’s no hiding in a delicate watercolor when you’re carving into wood, is there? The very process mirrored her themes. The repetitive, often arduous nature of preparing plates and blocks could even be seen as a metaphor for the relentless grind of the working-class lives she depicted.

Kollwitz was a formidable printmaker, primarily working with etching, lithography, and woodcut. Each demanded a specific kind of engagement, echoing the struggles she depicted. The biting acid in etching, for example, required precise control, and often multiple applications (or "stopping out" certain areas to protect them from further biting), to evoke the corrosive nature of grief or struggle – the slow, controlled corrosion, much like the relentless grind of poverty or the searing pain of loss. And the physical act of cutting into a woodblock? That's direct, unforgiving, with its stark black-and-white outcomes resonating deeply with the harsh, uncompromising truths she depicted about labor and hardship. The rugged textures and bold, often angular lines of her woodcuts, seen in pieces like "The Mothers", amplify the rawness and primal force of her subjects, almost making you feel the struggle in the fibers of the paper. Meanwhile, lithography offered a nuanced ability to depict subtle gradations of tone, which she used masterfully in works like "Bread" to portray the weary resignation and quiet desperation in the faces of the starving with a haunting realism that etching or woodcut couldn't quite achieve. It was a laborious process, much like the lives of the people she portrayed; you had to commit to every cut, every line.

These printmaking techniques also offered a directness and accessibility that was crucial for her message. Unlike a singular painting, prints could be reproduced and disseminated widely, reaching beyond the elite gallery walls and into the homes of ordinary people. This democratic aspect of printmaking aligned perfectly with her commitment to the working class, serving as a powerful, reproducible tool for social critique and advocacy. From an economic perspective, prints were far more affordable than paintings, making them accessible to a broader audience, including the very working-class families she sought to represent and empower. This meant her art truly became the art of the people, seen not just in galleries but prominently displayed in workers' halls, union offices, and anti-war publications, igniting discourse and empathy where it mattered most.

Here's a quick look at her primary printmaking techniques and their impact:

Medium | Technical Demand | Expressive Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Etching | Precise control of acid and needle; stopping out | Corrosive nature of struggle, intense detail in emotion, slow erosion of hope |

| Woodcut | Physical force, direct carving; reduction possible | Stark contrasts, raw power, primal force, angular lines, uncompromising truth |

| Lithography | Nuanced drawing, subtle tonal gradations | Haunting realism, weary resignation, psychological depth, delicate despair |

Take her early series, "A Weavers' Revolt" (1893-1897), inspired by Gerhart Hauptmann's play. Here, you see the brutal suppression of a Silesian weavers' uprising. In the etching "March of the Weavers", for instance, the figures are monumental, their faces etched with a mix of despair and defiant resolve, moving forward as a single, powerful mass. This series already showcased her dedication to social themes with dramatic compositions. Later, the "Peasants' War" cycle (1902-1908), executed in etching and aquatint, explored another historical uprising, imbuing the suffering of the oppressed with a timeless, universal dignity. In pieces like "Charge" from this series, she uses the dynamic power of the etched line to convey explosive energy and desperate rebellion, a stark contrast to the quiet grief of her later works. The very act of creation felt almost as weighty and uncompromising as her themes of suffering and resilience. This intense focus on human experience, distilled through the powerful lines of her prints, is a profound bridge to her unique place within the Expressionist movement.

Expressionism Reimagined: Soul Over Spectacle

Now, after discussing her powerful printmaking and the deeply personal wellspring of her themes, let's talk about how Käthe Kollwitz fits into the broader artistic currents of her time. Her intense depiction of inner turmoil firmly places her within the revolutionary artistic currents of her time, particularly the Expressionist movement. When we talk about Expressionism, my mind often conjures vibrant, often distorted colors and intense emotional landscapes. This movement, particularly in Germany, emerged in the early 20th century as a powerful response to the anxieties of industrialization, urban alienation, and a general disillusionment with academic traditions that prioritized idealized forms over objective truth. The Expressionists aimed to express internal subjective experience rather than objective reality, often through distorted forms and heightened emotion. Think of artists like Ernst Ludwig Kirchner or Franz Marc from the Die Brücke group (known for raw, primitivist forms and urban alienation) and Der Blaue Reiter (more focused on spiritual abstraction and color theory), or the intense, almost abstract canvases of Wassily Kandinsky. What unites them, despite stylistic differences, is this shared quest to externalize profound internal states and societal critique, reflecting the anxieties of a pre-war and inter-war Germany.

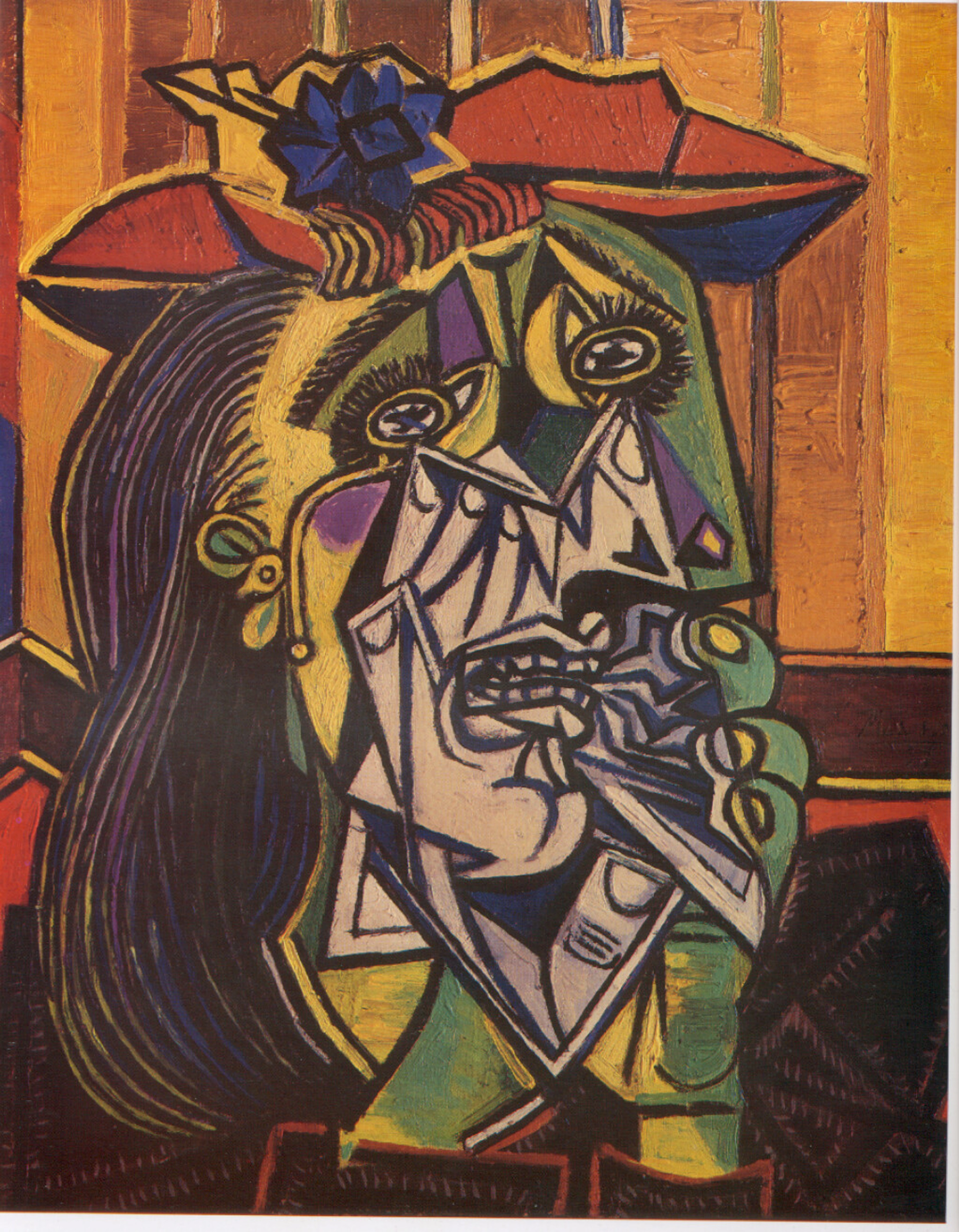

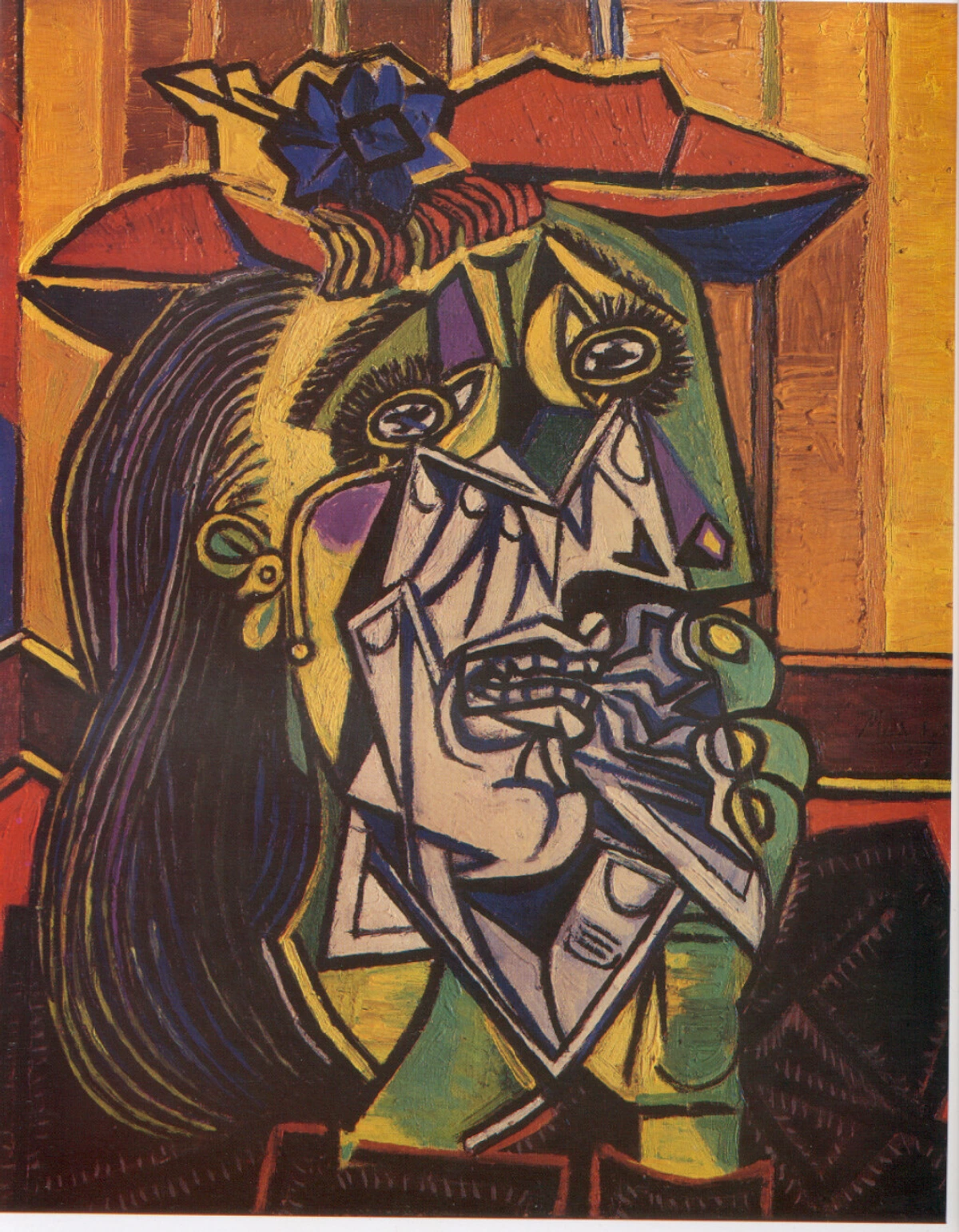

To truly understand Kollwitz's place in Expressionism, it's helpful to consider the broader movement's explorations of intense emotion, even if their stylistic approaches differed significantly from hers. For instance, while a Cubist artist like Picasso might explore grief through fragmented, vibrant forms in "Weeping Woman," Kollwitz approaches it with a stark, raw directness:

Kollwitz was definitely part of that spirit of Expressionism, even if her aesthetic wasn't about shocking colors or overt abstraction. This is where she truly stands out. Her Expressionism manifested in the way she distorted figures – not for abstract beauty, formal experimentation, or the exploration of color theory like a Kandinsky or Kirchner, but explicitly to heighten emotional impact and psychological depth. Those elongated, weary faces, the grasping hands, the hunched shoulders – they weren’t anatomically perfect, but they conveyed the crushing weight of grief and despair in a way academic realism, with its emphasis on objective, external representation, simply couldn't touch. It’s like she peeled back the skin to show you the aching soul beneath. She shared this profound focus on internal states and societal critique with some of her German Expressionist contemporaries like Max Beckmann, though his approach often leaned more towards satirical allegory and symbolic distortions rather than Kollwitz's raw, unmediated empathy. Still, both grappled with the fragmented human condition and the moral decay they perceived in post-war society, though Beckmann's often more aggressive, almost violent distortions serve a different allegorical purpose than Kollwitz's sympathetic rendering of the suffering. Other artists like Ernst Barlach, known for his somber sculptures and woodcuts, also shared Kollwitz's focus on the suffering human figure, albeit with a more monumental, often Germanic, folk-art inspired aesthetic.

She explored the raw emotion of the human condition, making her a seminal figure in German Expressionism, a movement defined by its focus on internal feelings over external appearances. She achieved this masterfully through stark lines and profound empathy rather than vibrant hues or fragmented forms like Egon Schiele might use to portray psychological anguish through contorted nudes, or Georg Baselitz's later, more aggressive deconstruction of the figure. Kollwitz's intensity was every bit as potent, but it was grounded in the visceral reality of human struggle. For me, her work is a powerful reminder that emotional resonance in art doesn't rely solely on a vibrant palette. Where my own studio often explodes with color, hers embraced the power of the monochrome, proving that the deepest truths can be conveyed through the most fundamental elements of line and form. And sometimes, when I'm wrestling with a new abstract idea, I find myself asking, "How would Kollwitz convey this feeling, stripped down to its core?" It's a surprisingly clarifying exercise, even for an artist whose canvas is awash in vibrant hues. It's a testament to art's power that such different palettes can convey such profound shared human experiences.

An Unflinching Gaze: Art as Social Conscience

It’s in this unflinching gaze on societal truths, building on her Expressionist approach to convey deep feeling, that Kollwitz’s power truly shines. Her social commentary wasn’t subtle; it was direct, heartfelt, and utterly devastating – a visual manifesto for change. She took the suffering of the ordinary person—the worker, the mother, the child—and made it monumental, aiming to provoke empathy and inspire a call for action. Her powerful works vividly illustrate the struggles of common people and advocate for social justice, placing her art firmly within the spirit of Social Realism in its subject matter. However, her unique artistic voice elevates her beyond simple categorization.

For me, Kollwitz's approach transcends mere depiction; it becomes Social Art – art driven by a moral imperative, intended to confront, to heal, to activate. The key distinction, I think, is this: where Social Realism often aims to document and critique social conditions objectively (think of early 20th-century American artists depicting farm workers, or Soviet artists glorifying labor), Kollwitz infuses her work with such profound personal and universal emotional weight that it moves beyond mere reportage. Her art doesn't just reflect society, but actively seeks to influence it, making the invisible visible and demanding a response. This concept of art as a moral and political tool, rather than solely an aesthetic one, can be traced back to figures like Eugène Delacroix or even Francisco Goya, though Kollwitz carved her own distinct, empathetic path. Kollwitz wasn't just observing; she was bearing witness, almost like a visual journalist of the human soul. When I see her portrayals of mothers clutching their dead children, or the weary faces of workers, I don't just see a picture; I feel the echo of their pain. It’s a powerful reminder that art can, and often should, be political. It should hold a mirror up to society, even if society doesn't like what it sees.

A piece that powerfully embodies this is her etching "Mother with Dead Child" (1903), a recurring theme throughout her career, where the mother’s body completely envelops the child, a primal gesture of protectiveness even in death, rendered with heavy, somber lines. But perhaps the most poignant reflection of this personal agony is her later sculpture, "Grieving Parents", dedicated to her son Peter, who died in World War I. Located at the Vladslo German war cemetery, the rough-hewn, almost monolithic forms of the parents' bodies, bowed under an unbearable weight of sorrow, kneeling in eternal lament, etched with universal agony, makes you wonder about the resilience and fragility of the human spirit. This shift from the stark lines of printmaking to the monumental, enduring forms of sculpture signals a desire for a more permanent, universally accessible memorial to grief, transcending the immediate and speaking to eternity. It’s a physical manifestation of the emotional 'scream' in her prints, moving from the personal anguish of one mother to the collective sorrow of all those scarred by conflict.

After World War I, her series "War" (1923), especially the powerful woodcut "The Mothers", screamed against the futility and brutality of conflict, showing women shielding their children with desperate, primal force, their faces contorted not just by grief but by an almost animalistic determination. Other impactful works include "The Survivors" (1919), which captures the haunting aftermath of conflict through the gaunt, bewildered faces of those left behind, and "Woman with a Heap of Dead" (1919), a stark woodcut illustrating the raw devastation and human cost of war with an almost unbearable intensity. And works like "Bread" (1924), depicting a starving family, illustrate not grand battles, but the quiet, dehumanizing devastation of poverty with the gaunt faces and desperate eyes of those struggling to survive. Her political stance was evident not just in her art but also in her public actions; she was an outspoken pacifist and a signatory to various anti-war manifestos, consistently using her public persona to advocate for peace and social change.

Kollwitz grounds her emotional intensity in the raw, tangible realities of human suffering and its profound social impact. It was always about the human cost, an empathetic social critique that felt both personal and universal, and continues to resonate today, much like we discuss in art as catalyst for social change. Her prints were not confined to elite galleries; they were often seen in workers' halls, union offices, and anti-war publications, truly becoming an art of the people. She recognized the inherent power in creating art that could be widely distributed, allowing her message to permeate the everyday lives of those she sought to represent and defend. Even now, her themes of human dignity amidst suffering, the plea for peace, and the fight against injustice are profoundly relevant to contemporary social issues and movements, reminding us of art's enduring power to challenge and console.

Her Legacy: A Voice That Echoes Through Time

Kollwitz’s impact extends far beyond her lifetime, a testament to the enduring power of her message. Her work was not always universally embraced; during the Nazi regime, her art was deemed "degenerate art" (Entartete Kunst) and removed from public display. Why? Because her unflinching focus on suffering, poverty, and the working class directly contradicted the Nazi ideology of a pure, idealized, and heroic Aryan aesthetic. They found her work depressing, pacifist, and devoid of the 'strength' they wished to project. Moreover, her depictions of suffering and her empathy for the marginalized were seen as undermining the collective nationalistic fervor, her pacifism directly opposed to their militaristic agenda, and her perceived socialist sympathies were anathema. This act of suppression only solidified its challenging and subversive power – a potent testament to art's ability to speak truth to power, even when silenced. She continued to create, quietly resisting through her art, even as she faced personal ostracization and the devastation of World War II until her death in 1945, her focus unwavering on human compassion.

Yet, her unflinching gaze paved the way for future artists to use their platforms for social change, profoundly influencing later generations of politically engaged artists. Her mastery of printmaking also secured her place as one of the most significant graphic artists of the 20th century, inspiring countless subsequent printmakers and graphic designers who sought to combine artistic skill with profound social messaging. Her impact can be seen in the lineage of artists who champion humanitarian causes through their work, extending far beyond the confines of German Expressionism to movements like Social Realism, protest art, and contemporary socially engaged art practices. Artists such as Ben Shahn in America, or even later figures like William Kentridge, echo her profound humanism and commitment to social critique through graphic means. Her work has also been a foundational inspiration for feminist artists who explore themes of motherhood, labor, and women's experiences of war and grief.

The clarity and courage she showed in translating inner turmoil into form is something I constantly return to, even if my palette explodes with color where hers is muted, much to my studio's chagrin! It’s this unvarnished truth that I grapple with in my own artistic journey. I remember seeing a small Kollwitz etching in a quiet gallery once, years ago, and being absolutely floored by the sheer emotional force emanating from those simple, black lines. It was a profound lesson in how much can be said without a single splash of color. When I think about the themes I explore, the vibrant colors I choose, I'm always reminded that the intention behind the art is what truly matters. What do you want your art to do? What message are you leaving behind? For Kollwitz, it was about bearing witness, honoring the forgotten, and protesting injustice – a deeply personal act of activism. While I may express different truths through my contemporary art prints, that foundational desire to connect, to evoke feeling, to reflect on the human experience, is something she inspires in me daily. Her journey also saw a subtle evolution in her style, from the earlier, more naturalistic etchings of social protest to the later, more simplified and monumentally expressive woodcuts, reflecting an increasing distillation of emotion.

It’s a powerful lesson. How can we, as creators today, use our platforms to amplify marginalized voices, as Kollwitz so powerfully did? Her legacy challenges us to find our own answers, reminding us that empathy remains a revolutionary act. I've often thought about how her spirit would resonate with the Den Bosch museum's collection, sparking new dialogues about art and humanity, bridging historical insight with contemporary perspectives. Ultimately, Kollwitz teaches us that art, in its purest, most empathetic form, has the capacity to not just reflect the world, but to move hearts and minds, enduring through time as a beacon of human conscience. It's a testament to art's power that such different palettes can convey such profound shared human experiences.

Frequently Asked Questions About Käthe Kollwitz

Given her powerful impact and enduring relevance, it's no surprise that questions about Käthe Kollwitz continue to arise. Here are some of the recurring ones that often make me ponder her profound influence:

Q: What artistic movement is Käthe Kollwitz associated with?

A: Käthe Kollwitz is most closely associated with Expressionism, particularly German Expressionism. While her visual style, characterized by a muted palette and stark lines, differed from some of her more colorful contemporaries like Kirchner or Nolde, her profound focus on raw emotion, psychological depth, and incisive social critique aligns perfectly with the movement's core tenets of expressing internal feelings over external appearances. Like Ernst Barlach, she channeled the anxieties of her era into powerful, often somber, figurative works.

Q: What were the main themes in Käthe Kollwitz's art?

A: Kollwitz's art predominantly explored themes of war, poverty, maternal love, grief, death, social injustice, social commentary, and the suffering of the working class. These themes were profoundly shaped by her personal experiences, including the loss of her son and grandson in world wars, and her daily observations of working-class hardship. Her work offers a powerful social critique and often connects with Social Realism, but ultimately transcends it through her unique Social Art philosophy, driven by a deep moral imperative and empathy.

Q: What mediums did Käthe Kollwitz primarily use?

A: Kollwitz was a master printmaker. She primarily worked with etching, lithography, and woodcut, choosing these mediums for their ability to convey stark contrasts, powerful lines, and a raw, immediate emotional impact. This mirrored the gravity of her subjects and allowed for wide dissemination of her message, making her art accessible to a broader audience for whom she advocated. She understood that the very process of these mediums could amplify her message of struggle and resilience, allowing her to explore the corrosive nature of grief in etching or the uncompromising truth of hardship in woodcuts.

Q: Why is Käthe Kollwitz considered important today?

A: Kollwitz remains important today for her unparalleled ability to depict universal human suffering with profound empathy and honesty. Her work serves as a powerful historical document and a timeless testament to the human spirit's resilience amidst adversity, continuing to inspire discussions on social justice and the role of art in society. Her courage in addressing difficult truths paved the way for later artists engaging with social and political themes, making her a seminal figure in art as catalyst for social change. Her legacy also underscores that art's emotional power is not solely dependent on color, but on the depth of its message and the honesty of its execution. Furthermore, her focus on the female experience of war, grief, and labor makes her a foundational figure for many feminist artists.

Q: How did Käthe Kollwitz influence later artists or movements?

A: Käthe Kollwitz profoundly influenced subsequent generations through her unwavering commitment to social commentary and her mastery of graphic arts. She is considered a foundational figure for political and activist art, demonstrating how artistic expression could directly advocate for humanitarian causes. Her techniques and thematic depth inspired countless printmakers, illustrators, and graphic designers who sought to combine artistic skill with potent social messaging, ensuring that art could serve as a powerful tool for social consciousness and change. Her influence is evident in subsequent movements like Social Realism, documentary art, and contemporary protest art movements, where artists continue to use their platforms to address social inequities and human suffering.