The Ultimate Guide to Egon Schiele: Raw Emotion & Expressionism

Dive deep into the unsettling, powerful world of Egon Schiele. Explore his life, his radical Expressionist art, and why his raw honesty still resonates today.

The Ultimate Guide to Egon Schiele: Raw Emotion & Expressionism

You know that feeling when an artist’s work just… stops you? Like a punch to the gut, or a sudden, stark realization? That’s Egon Schiele for me. His art isn’t about comfort or beauty in the traditional sense; it’s about an almost unbearable honesty, a mirror reflecting the raw, often unsettling, truths of being human. I remember the first time I encountered one of his self-portraits, and honestly, I was a little shaken. All those twisted limbs, gaunt features, that confrontational stare – it demanded a response, and I gave it, reluctantly at first, then with a growing fascination. That unsettling feeling? That’s where his genius lies, I think. I remember the first time I saw one of his self-portraits – all twisted limbs, gaunt features, and an almost confrontational gaze. It wasn’t beautiful in the classical sense, not comforting or escapist. In fact, some might even call it 'ugly.' But for Schiele, this intentional departure from conventional aesthetics was precisely how he conveyed something profoundly real. It demanded a response, and frankly, I was a little unsettled, which, I've come to realise, is precisely his genius – his absolute refusal to conform to polite society's expectations of art.

He emerged from turn-of-the-century Vienna, a hotbed of intellectual and artistic ferment, but even within that crucible of change, Schiele was an outlier. This was the era of Freud's groundbreaking psychoanalysis, Wittgenstein's philosophical inquiries, and Gustav Mahler's revolutionary compositions – a city pulsating with new ideas and a challenging of old norms. In such a vibrant, yet deeply traditional society, Schiele's raw, often provocative work was destined to both captivate and scandalize. He seized upon the burgeoning ideas of Expressionism – the radical notion that art should convey subjective emotion and internal psychological states rather than objective reality – and pushed them to an almost unbearable extreme. I often wonder what it must have been like to live in his time, to see such raw, exposed vulnerability and angst. It certainly wasn’t for the faint of heart, and it certainly isn't for mine on a sleepy Sunday morning, but it's utterly compelling all the same.

Speaking of heart, let's pull back the curtain a little more on the man behind the art, shall we?

Who Was Egon Schiele? A Life Lived on the Edge

Egon Schiele's story is a tragically short but incredibly potent one, a whirlwind of intense creation packed into just 28 years. Born in 1890, Egon Schiele’s childhood was marked by early tragedy. His father, a station master, succumbed to syphilis when Schiele was just 15, an event that, I believe, cast a long shadow over his artistic psyche. This profound personal trauma, the confrontation with illness and death at such a formative age, deeply informed the raw angst, vulnerability, and stark emotional landscapes so evident throughout his oeuvre. His younger sister, Gerti, also became an important early model and subject, sharing a similarly intense bond with the artist. It’s hard to imagine the weight of that loss shaping an already sensitive young man. He was a prodigious talent, gaining admission to the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts at the incredibly young age of 16. You'd think that would be the dream, right? But as I’m sure many of us can relate to, sometimes the rules just get in the way of what you really need to say. Schiele quickly found the Academy’s conservative, tradition-bound teachings stifling. He yearned for freedom, a space where raw emotion and subjective vision could flourish, rather than adhering to rigid academic canons.

It wasn't long before he connected with the art world's rebel, Gustav Klimt, the godfather of the Vienna Secession. Klimt, already a revered master and the spiritual godfather of the Vienna Secession, recognized an extraordinary, untamed talent in the young Schiele. He offered encouragement, mentorship, and even exchanged drawings with him, perhaps seeing in Schiele a younger, bolder spirit ready to push boundaries further. Yet, while Klimt’s canvases shimmered with opulent decorative symbolism and veiled sensuality, Schiele’s nascent vision was starker, darker, and unflinchingly exposed. He admired Klimt but knew his own path required a deeper dive into the raw, often uncomfortable, truths of the human psyche, shedding the decorative facade completely. He soon broke away from the Academy, a rebellious act that led him to co-found the Neukunstgruppe (New Art Group) in 1909. Though short-lived, this group was a vital outlet for his radical vision. This move was a deliberate statement, a search for an artistic community that embraced the radical subjectivity and intense emotional expression he championed. It was here, amongst like-minded rebels, that he truly began to forge the distinctive path that would define him as a central figure in Austrian Expressionism, albeit a path often fraught with challenges.

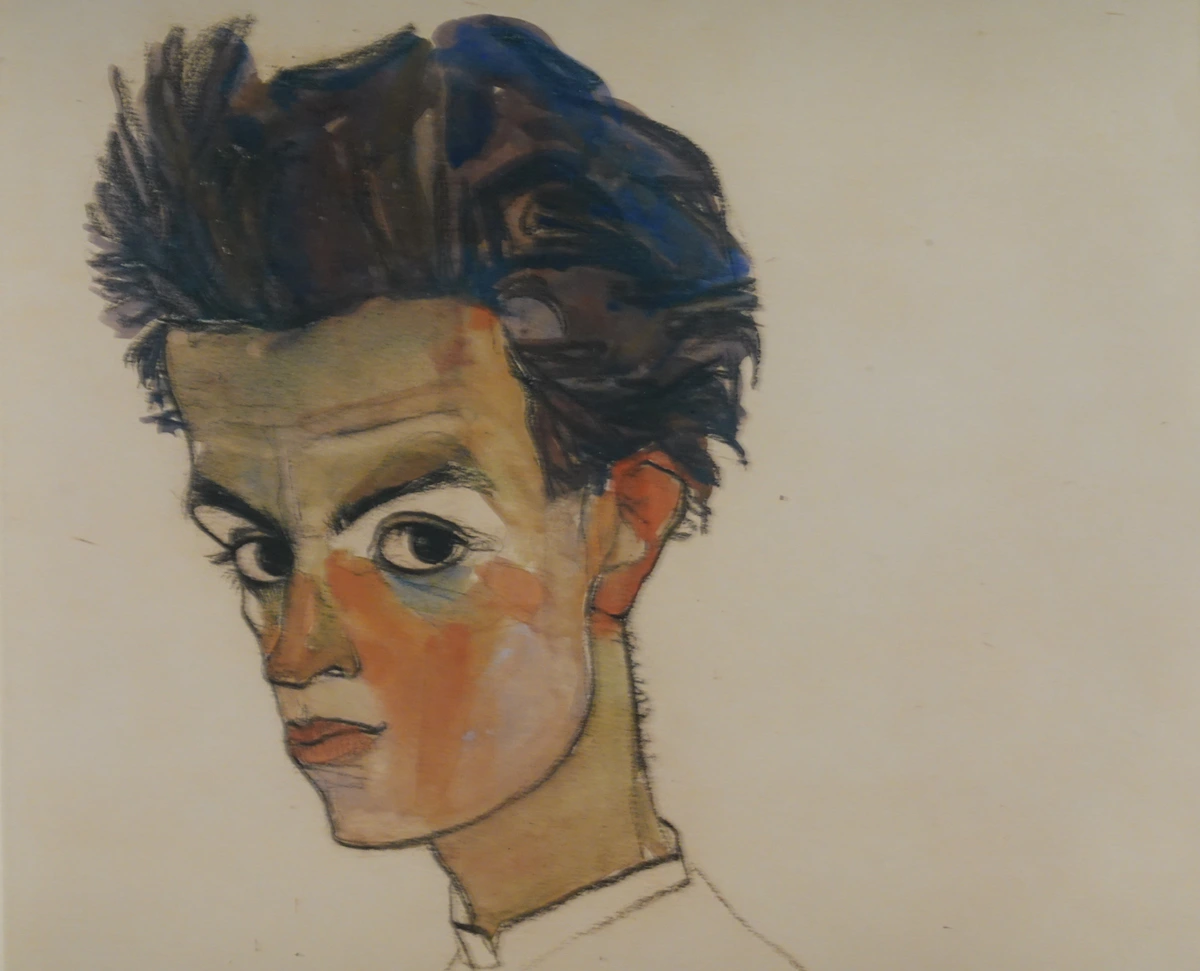

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/7f/Egon_Schiele%2C_Self_Portrait%2C_1910%3B_Leopold_Museum%2C_Vienna_%281%29.jpg, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0

The Language of Anguish: Schiele's Expressionist Vision

When I think about Schiele and Expressionism, I think about turning inward. While other artists might have been concerned with capturing a moment or depicting a beautiful scene, Expressionists, and Schiele especially, were after something deeper: the internal state. They wanted to show the world not as it appears to the eye, but as it feels to the soul, often positioning the artist as a seer, revealing uncomfortable truths. If you're interested in understanding this movement more broadly, I’ve also put together an ultimate guide to Expressionism that you might find insightful.

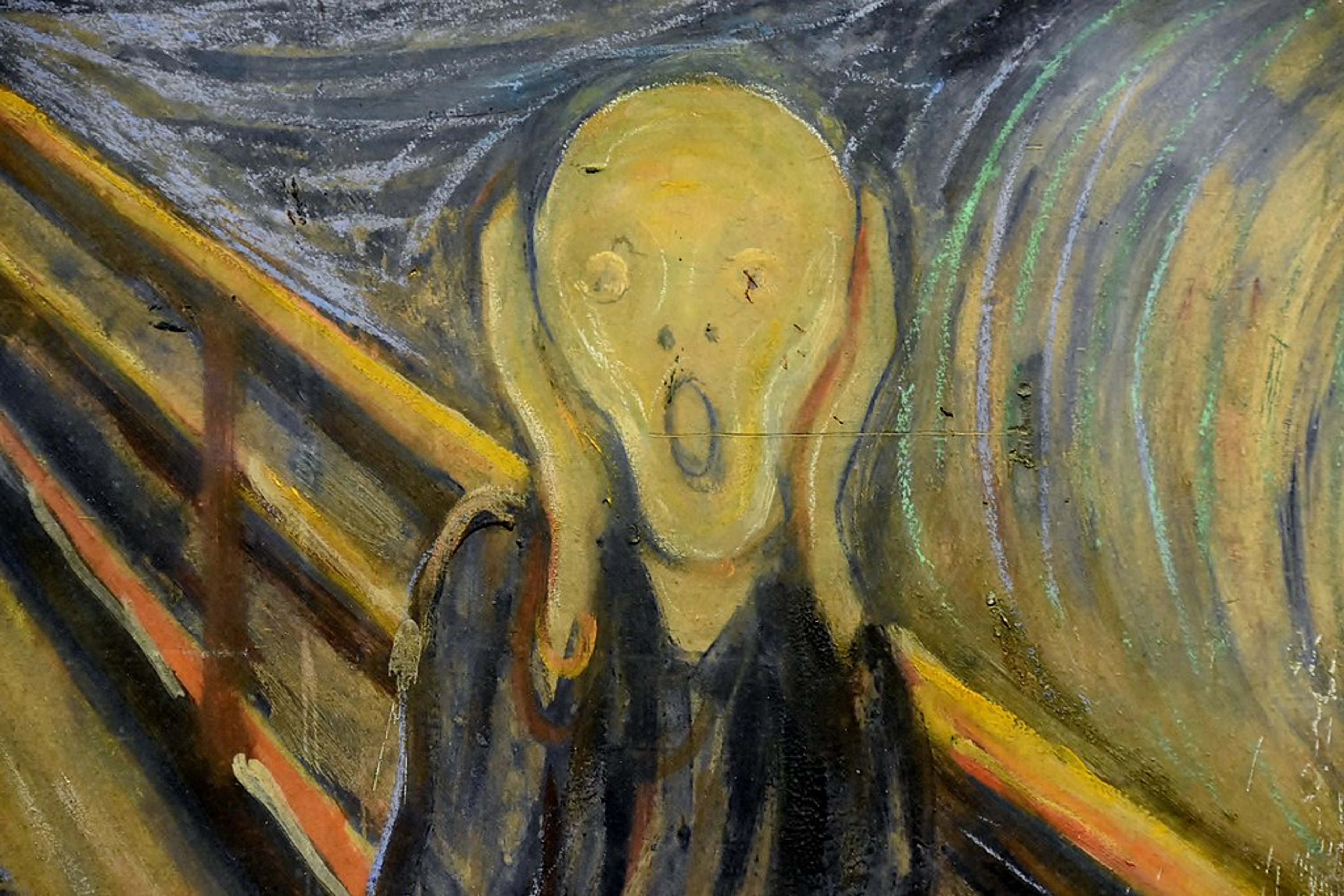

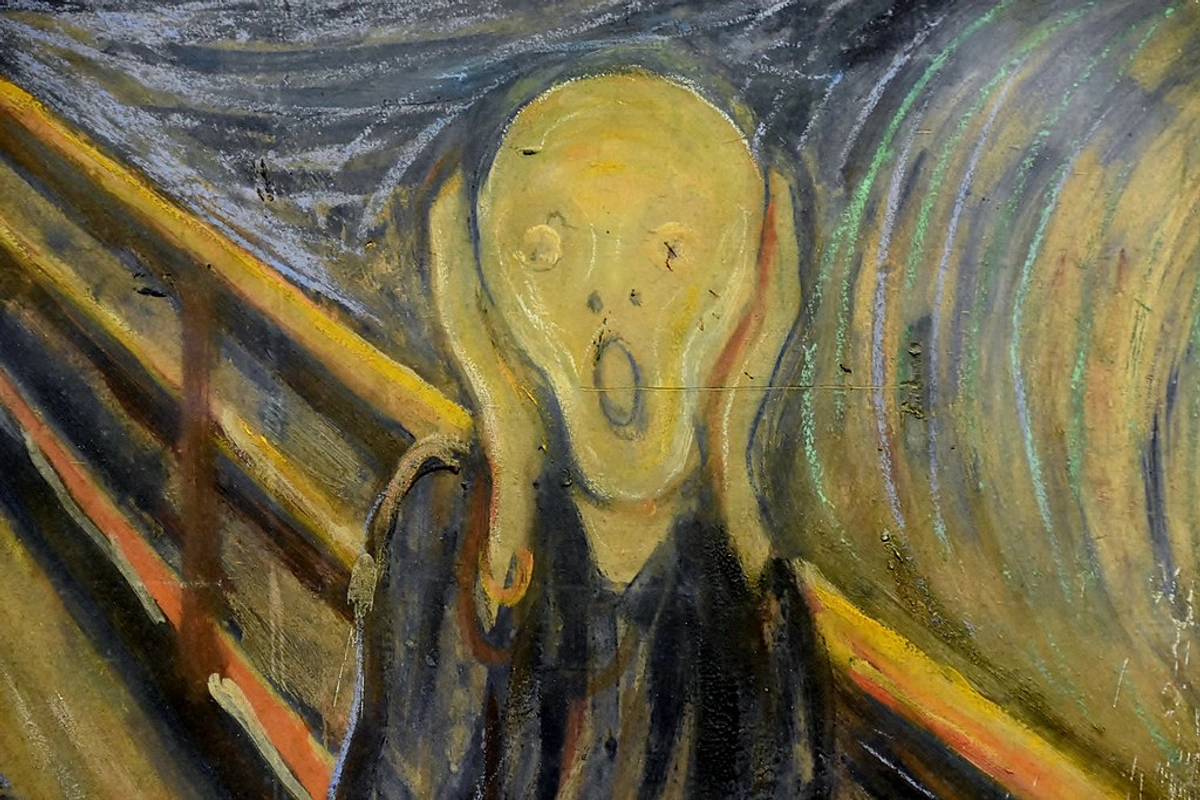

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Edvard_Munch,_The_Scream,_1893,National_Gallery,Oslo%281%29%2835658212823%29.jpg, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0

Schiele's unique contribution was his unflinching depiction of human vulnerability, often through distorted, emaciated figures, contorted poses, and a raw, almost agonizing sense of self-exposure. He stripped away convention, revealing psychological landscapes of anxiety, desire, and alienation. His lines are sharp, almost brutal, his colours often muted or sickly – chosen for their psychological intensity rather than their descriptive quality – and his frequent use of stark, empty backgrounds amplifies the sense of isolation and psychological drama, adding to the intense, unsettling mood. It’s like he's laying bare his own nerves, and by extension, ours too.

Wally Neuzil: Muse, Model, and Lover

Before his marriage, one figure loomed large in Schiele's personal and artistic life: Walburga "Wally" Neuzil. For four intensely creative years, from 1911 to 1915, Wally was his primary model, muse, and companion. She appeared in some of his most significant works, her striking features and expressive body language becoming synonymous with his unflinching gaze into the human condition. Their relationship, though controversial at the time, was a period of immense artistic output for Schiele. He captured her with a profound intimacy and emotional honesty that few artists achieve, showing her not just as a model, but as a complex individual, full of life and vulnerability. I often wonder about the stories behind those eyes in his portraits of her.

Self-Portraits: A Soul Unveiled

Perhaps nowhere is Schiele’s radical honesty more evident than in his prolific self-portraits. He painted himself tirelessly, exploring every facet of his own psyche – confident, tormented, vulnerable, defiant, and at times, utterly despairing. It wasn't about vanity; it was an intense, almost forensic examination of the self, a performative act of laying bare his innermost turmoil, perhaps even foreshadowing later performance and body art. Through exaggerated gestures, contorted limbs, and searing gazes, he transmuted his internal struggles into visual statements, making us confront the uncomfortable truths he found within himself. This relentless introspection reminds me a little of other artists who used self-portraits as a form of deep psychological exploration, like a certain ear-incident-prone Dutch master like Vincent van Gogh, or even the intense self-scrutiny seen in some of Jean-Michel Basquiat's raw works, though their styles diverge wildly. It's that shared commitment to baring the soul, even if the aesthetic language differs.

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/b/b3/Self_portrait_Egon_Schiele_1911.jpg, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0

His self-portraits are rarely flattering. Instead, they are an inventory of human emotion, often depicting him nude, exposed, or with exaggerated gestures and confrontational gazes that speak volumes about internal turmoil. I mean, imagine having the courage to present yourself, warts and all, to the world like that. It’s a testament to his conviction.

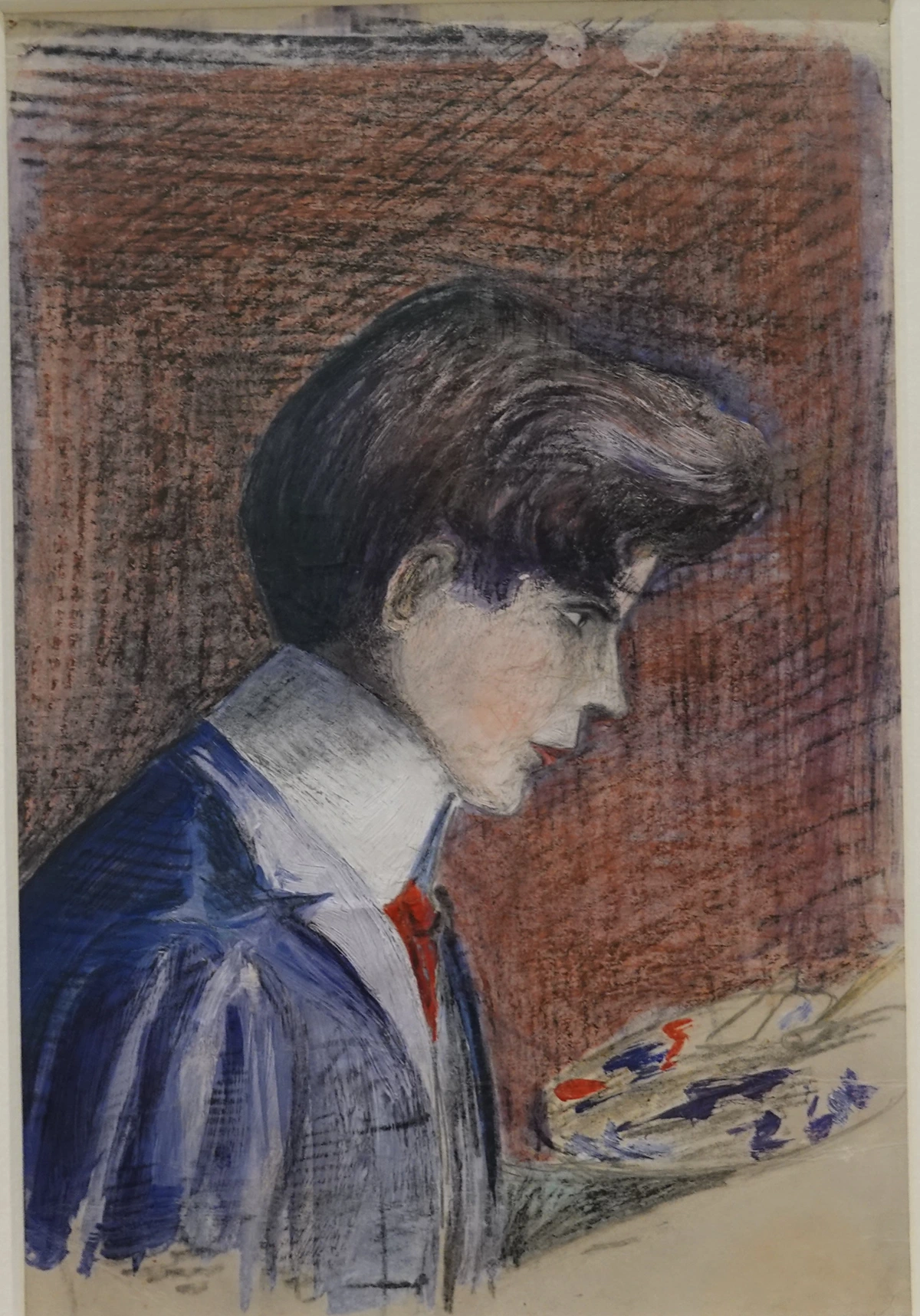

Beyond the Self: Portraits of Others

While his self-portraits are arguably his most famous, Schiele also applied his intense psychological lens to his sitters. Friends, family, and patrons were subjected to the same unflinching gaze, their inner lives often seemingly laid bare through his distinctive lines and unsettling compositions. These weren't society portraits designed to flatter; they were studies in human vulnerability, often revealing isolation, melancholy, or a fragile defiance. He had this incredible knack for seeing beyond the facade, don't you think?

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/0/03/Egon_Schiele%2C_Self_Portrait_with_Palette%2C_1905%3B_Leopold_Museum%2C_Vienna.jpg, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0

The Human Form: Beyond the Nude

Schiele's nudes are perhaps his most controversial works, and for good reason. They’re emphatically not idealized or classical; in fact, they often lean into the 'grotesque.' They are raw, sometimes awkward, almost skeletal, and charged with a palpable sense of sexuality, anxiety, and existential vulnerability. He wasn’t aiming for beauty but for uncomfortable truth, challenging societal taboos head-on. He wasn't depicting beauty as much as he was deliberately de-beautifying the form, instead depicting the raw experience of having a body, with all its frailties, desires, and existential angst. It's a stark contrast to almost everything that came before him, and even to many contemporaries. He stripped the human form of its social facade, revealing something much more primal.

Landscapes and Cityscapes: Echoes of the Soul

Even Schiele's landscapes and cityscapes, which at first glance might seem like a departure from his intense figurative work, nonetheless carry his unmistakable unique emotional weight. They aren't picturesque; they're often stark, brooding, and pointedly devoid of human presence, as if reflecting an acute internal loneliness or a psychological state. Buildings appear to slouch, their windows like vacant eyes; trees seem skeletal, their branches reaching like anguished fingers. He meticulously imbued the external world with his internal anxieties, often depicting isolated houses or stark urban vistas devoid of human presence. It’s a powerful trick, making even a seemingly mundane street corner feel profoundly unsettling, intensely alive with a quiet, brooding emotion.

Controversy and Conviction: Schiele’s Unwavering Path

It’s probably not a surprise that Schiele’s radical approach stirred up significant controversy. His raw depiction of sexuality and the human form led to accusations of obscenity, and in 1912, he was even imprisoned for a short period on charges of immorality and kidnapping (though the latter was dismissed). During his 24-day imprisonment, which he meticulously documented, he continued to draw, creating haunting works that expressed his isolation, despair, and defiance. These "prison drawings" are a testament to his unyielding spirit, a visceral record of his confinement. He even drew with his left hand when his right was injured, finding a way to keep creating. Talk about conviction, right? Imagine being told your art is immoral, condemned, and you just keep going, fueled by the very experience of that condemnation.

Despite the moral outrage and significant public disapproval his work often provoked, Schiele achieved some critical recognition during his lifetime, notably participating in the highly influential Vienna Secession exhibition of 1918. Yet, he never wavered from his artistic vision.

Edith Harms: A Brief Turn Towards Maturation

In 1915, Schiele married Edith Harms, a pivotal moment that coincided with a subtle, though observable, shift in his work. While his raw intensity never faded, some of his later pieces, particularly family portraits and the few allegorical works, show a touch more introspection and a less overtly confrontational approach. The Spanish Flu epidemic, tragically, cut this period of maturation short, claiming Edith’s life, then his own, in 1918. His final works, created in the shadow of this impending global crisis, hinted at a new depth and a more resolved, though still poignant, artistic voice. It leaves us to wonder what artistic paths he might have explored had he been granted more time. He continued to explore the depths of human psychology with an honesty that few artists dared to approach. His persistence in the face of adversity is a powerful lesson for any creative soul. I mean, sometimes I struggle to finish a painting when it's just not quite working out, let alone when I'm facing public condemnation! It really puts things into perspective.

The Legacy: Schiele's Enduring Impact

Schiele’s life was cut short by the Spanish Flu epidemic in 1918, at the age of 28, just three days after his pregnant wife Edith also succumbed to the disease. It’s heartbreaking to think of the work he might have created had he lived longer.

Yet, even in his brief career, he left an indelible mark on art history. His raw, psychological approach profoundly influenced subsequent generations of artists, particularly those grappling with themes of identity, angst, and the human condition. Beyond obvious connections, his daring self-exploration paved the way for a more personal and introspective art, impacting figurative painters and those concerned with psychological realism throughout the 20th century. You can see echoes of his expressive power in movements like Neo-Expressionism, where artists again embraced intense subjectivity and figurative distortion, continuing his legacy of artistic bravery. His unflinching honesty paved the way for a more personal, introspective, and often unsettling approach to art, almost prophetically foreshadowing the psychological complexities explored in later 20th-century movements.

To me, Schiele's work is a constant reminder of the power of vulnerability in art. It's about looking beneath the surface, embracing the discomfort, and finding beauty not in perfection, but in the raw, messy truth of existence. And that, I believe, is a lesson that transcends time. It reminds me that sometimes, the most profound beauty isn't found in polished perfection, but in the courage to face and express the raw, messy truth of our existence. His intensely personal struggles, in a curious twist of fate, became universally resonant.

Your Burning Questions Answered: Frequently Asked Questions about Egon Schiele

I know, I know, there’s a lot to unpack with Schiele. So, let’s tackle some of the common questions you might have about this fascinating artist.

What style of art is Egon Schiele known for?

Egon Schiele is primarily known for his intensely personal and psychologically charged style of Expressionism. His art features distorted figures, sharp lines, and a raw emotional intensity, focusing on themes of identity, sexuality, and existential angst rather than traditional beauty.

Why is Egon Schiele considered an important artist?

Schiele is important because he didn't just push the boundaries of Expressionism; he shattered them, offering an unprecedented level of psychological insight and emotional rawness in his depictions of the human form and self-portraits. He bravely explored uncomfortable, often taboo, aspects of the human psyche, challenging societal conventions and influencing countless artists who sought to express internal states over external realities. His radical honesty redefined what art could be, and for that, he remains a monumental figure in Viennese Modernism.

What mediums did Egon Schiele typically use?

Schiele primarily worked with drawing and painting, often employing a rapid, almost frenetic technique that captured raw immediacy. He was prolific in watercolour, gouache, and pencil on paper, favoring absorbent papers that allowed for quick, expressive lines and washes. His oil paintings, though fewer in number, also exhibit his distinctive, intense style, often built up with thin layers to emphasize line and form.

Where can I see Egon Schiele's art today?

Many of Schiele's most significant works are housed in museums, particularly in Austria. The Leopold Museum and the Belvedere in Vienna hold extensive collections, with the Leopold holding the largest and most comprehensive array of his works, offering an unparalleled deep dive into his oeuvre. Other major institutions worldwide also feature his work, including the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York and the Tate Modern in London. If you're passionate about art history, visiting these collections in person offers an unparalleled experience to see his audacious vision up close.

Did Egon Schiele have a specific artistic philosophy?

While he didn't publish a formal manifesto, Schiele's art was guided by a profound philosophy of self-expression and honesty. He believed art should delve into the inner life, revealing the spiritual and psychological truths of existence, however uncomfortable they might be. His goal was not to depict beauty but to expose raw feeling, to make visible the unseen anxieties and desires of the human soul. He was, in essence, a visual philosopher of the psyche.

Who were Schiele's artistic contemporaries in Vienna?

Schiele was part of a vibrant artistic and intellectual scene in fin-de-siècle Vienna. Key contemporaries included his mentor Gustav Klimt, fellow Expressionist Oskar Kokoschka, and Richard Gerstl (whose work shares a similar intensity). Architects like Otto Wagner and Josef Hoffmann, and designers from the Wiener Werkstätte, also shaped the broader artistic landscape, though Schiele's path was decidedly more solitary and provocative.

Ready to Dive Deeper?

I hope this guide has given you a glimpse into the compelling, often unsettling, world of Egon Schiele. His art, for all its raw emotion and confrontational honesty, offers a profound insight into the human condition that remains relevant and powerful today. What do you think? Does his work grab you the way it does me? Perhaps it’s time to revisit those intense gazes and twisted forms, and let them speak to your soul once more.