Unpacking Guernica: Picasso's Masterpiece and Its Enduring Meaning

Ever wondered about the true meaning behind Picasso's Guernica? Join me as I dive into the heart-wrenching symbolism, historical context, and personal impact of this iconic anti-war painting.

Guernica: A Personal Odyssey Through Picasso's Anti-War Scream

Sometimes, you encounter a piece of art that doesn't just hang on a wall; it grabs you by the soul and shakes you. For me, that’s always been Picasso’s Guernica. I first saw it years ago, and I swear, the sheer size and raw, monochrome brutality hit me like a physical blow. It felt less like admiring a painting and more like staring into a gaping wound of human anguish, a collective scream frozen in time. The distorted figures, the wide-eyed terror, the overwhelming chaos—it’s not something you simply observe. It's something you feel, deep in your gut, reverberating with an unsettling truth about humanity. Beyond its undeniable anti-war message, what exactly did Picasso weave into those stark greys, blacks, and whites that continues to seize us today? That's the journey I want to take with you. Because for me, truly understanding Guernica isn't just an academic exercise in art history; it's an invitation to confront our own capacity for both immense creation and devastating destruction, to grapple with historical echoes that refuse to fade. It's a painting that demands engagement, a visceral conversation starter, and a profound emotional experience all rolled into one colossal canvas. What truly grips me, even now, is how it speaks a universal language of suffering, transcending any particular time or place. Guernica isn't merely a historical document; it's a mirror held up to every instance of human-inflicted devastation, forcing us to face the uncomfortable truths about conflict and its indelible mark on the innocent. And honestly, it gets under your skin, doesn't it? It makes you realize that its themes are, tragically, never truly 'history' but rather a recurring, terrifying nightmare. This journey isn't just about analyzing brushstrokes; it's about understanding how art can hold a mirror to our deepest fears and most urgent calls for peace, a conversation that feels as vital now as it did then. I promise, by the end of this, you’ll not just see Guernica; you’ll feel it even more profoundly, and hopefully, find your own voice in its enduring scream. It makes you realize that its themes are, tragically, never truly 'history' but rather a recurring, terrifying nightmare. It’s a work that refuses to be ignored, a stark, uncomfortable, yet absolutely essential dialogue that I believe, with every fiber of my being, we need to keep having. It’s a masterpiece that challenges complacency, a persistent, monochrome scream demanding our perpetual engagement.

But here's the thing about Guernica: it's not a painting you simply observe. It's a dialogue, a harrowing whisper across decades, asking us to confront the uncomfortable truths of our shared history. And in this journey, I invite you to peel back the layers with me, to move beyond initial shock and truly decode the language of its terror, its hope, and its enduring message. It's a deeply personal conversation, a challenging but necessary one. For me, connecting with a piece like Guernica isn't just about art history, it's about connecting with something profoundly human, something that echoes across time and speaks to the very soul of our capacity for both darkness and light. It's about finding our own voice in that collective scream.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/malisia/5482110937, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.0/deed.en

The Spanish Civil War: A Crucible of Conflict

Before we dive deeper into the painting itself, it’s crucial to understand the tempestuous backdrop against which Guernica was created. The Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) wasn't just a local conflict; it was a brutal ideological showdown that captivated—and horrified—the world, becoming a chilling dress rehearsal for World War II. It pitted the democratically elected Second Spanish Republic, supported by a diverse array of progressive forces, against a Nationalist rebellion led by General Francisco Franco, who quickly garnered decisive military and ideological support from fascist Italy and Nazi Germany. What makes it so poignant, I think, is that it wasn’t merely a fight for territory, but for the very soul of a nation, a clash between democracy and authoritarianism, progress and tradition—a truly existential struggle. It’s a stark reminder that sometimes, the battles we fight are as much about ideas as they are about land, and those ideas can tear a nation apart. The complexity of the conflict was staggering; it wasn't just a simple binary. Within the Republican side, there was a dynamic and often tense coalition of socialists, communists, anarchists, and regional nationalists, each with their own vision for Spain's future. It wasn't just internal, either; the Republicans garnered some limited, albeit crucial, international support from the Soviet Union and Mexico, and perhaps most famously, from thousands of idealistic volunteers from around the world who formed the International Brigades. These brigades, made up of writers, artists, and ordinary citizens, crossed borders to fight fascism, embodying a truly inspiring, yet ultimately tragic, testament to human solidarity against tyranny. Meanwhile, Franco's Nationalists drew strength from conservative monarchists, the Catholic Church, and the powerful Falange (a fascist political party), creating a formidable, albeit brutally unified, opposition. Crucially, they received overwhelming military and logistical backing from Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany, who saw Spain as a proving ground for their modern weaponry and Blitzkrieg tactics, making it a chilling dress rehearsal for the global conflict to come. It was a nation fractured, and the world watched, often with a horrifying mixture of fear and opportunism, many nations choosing non-intervention, a decision that still echoes with historical 'what ifs' today. I sometimes wonder if the world truly understood the gravity of what was unfolding, or if we were all just watching a slow-motion catastrophe, unable or unwilling to intervene.

More Than Just Paint: The Roar of History

Let’s set the scene, shall we? The year is 1937, and Spain is in the agonizing throes of a brutal civil war. On one side, the elected Republican government, and on the other, Nationalist forces led by General Francisco Franco, backed by the rising fascist powers of Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. It was a conflict that drew international attention and interventions, a crucible of ideologies clashing, foreshadowing the global conflict that was just around the corner. But beyond being a mere prelude, the Spanish Civil War itself was a devastating clash of values—democracy versus authoritarianism, progress versus tradition—that tore Spain apart and served as a chilling preview of the broader ideological battles that would soon engulf Europe. It was a struggle for the very soul of a nation, and its brutality shocked the world, setting a grim precedent for the total warfare to come. On one side, the Republicans, a coalition of democrats, socialists, communists, and anarchists, fighting to preserve the fragile Spanish Republic. Many idealistic volunteers from around the world even formed International Brigades, crossing borders to defend democracy against the rising tide of fascism – a truly inspiring, albeit ultimately tragic, testament to human solidarity. On the other, Franco's Nationalists, a conservative, monarchist, and fascist-leaning faction, heavily supported by Hitler and Mussolini, who saw Spain as a testing ground for their advanced weaponry and blitzkrieg tactics. Then, on a quiet Monday, April 26th, something truly horrific shattered the peace: the Basque town of Guernica was subjected to a merciless aerial bombardment. For over three hours, waves of Nazi German Luftwaffe (specifically the Condor Legion, equipped with Heinkel He 111 bombers and Messerschmitt Bf 109 fighters, which were advanced for their time and delivered devastating payloads with chilling precision) and Fascist Italian Aviazione Legionaria, flying under the guise of the Spanish Nationalists, pounded the unsuspecting town. It's estimated that hundreds of civilians were killed or wounded in this brutal attack, which leveled over 70% of the town and sparked global outrage, igniting fears about the future of warfare. The deliberate timing on a market day, when the town was bustling with civilians, including women and children, undeniably underscored its nature as an act of terror, not a military strategy. Can you imagine the sheer terror? The roar of those planes, the explosions, the realization that there was nowhere to hide, as wave after wave unleashed a hellish firestorm. Their objective was not just strategic, but deeply psychological: to demoralize the Republican resistance and spread terror among the civilian population. This wasn't just another bombing; it was a deliberate, calculated experiment in terror tactics, testing the effectiveness of carpet bombing against civilians in an urban setting. The German Luftwaffe's Condor Legion, under Hitler's command, used Guernica as a grim laboratory, perfecting methods that would soon be unleashed across Europe, marking a terrifying escalation in the dehumanization of warfare. This deployment included the advanced Heinkel He 111 bombers, whose speed and payload were devastating, and the Messerschmitt Bf 109 fighters, which provided air superiority and strafing capabilities. For them, Guernica was a live-fire exercise, a brutal proving ground for the Blitzkrieg tactics that would define World War II. The sheer, systematic efficiency of the destruction was as shocking as its brutality, making it a chilling blueprint for future terror. Guernica, while not a military target in the traditional sense, was a cultural heart of the Basque region, and its destruction served as a potent symbol of brutal psychological warfare. The market day timing was no accident; it maximized civilian casualties and terror. It was a brutal, indiscriminate attack, a chilling demonstration of total warfare against non-combatants. The town was not just devastated; it was systematically obliterated, a chilling experiment in terror bombing that forever changed the face of modern warfare. It was a deliberate act, designed to break civilian morale and sow fear. And honestly, it makes you wonder about the minds behind such decisions, doesn't it? To use an entire town and its people as a horrifying blueprint for future destruction, demonstrating a callous disregard for human life that still shocks me. The deliberate choice of a Monday, market day, further amplified the tragedy, ensuring the town was bustling with civilians, including women and children, making the targeting undeniably an act of terror rather than military strategy. The global outrage that followed was swift and widespread, with reports in international newspapers immediately condemning the atrocity and igniting widespread fears about the future of warfare. It's almost unfathomable to think that this quiet market town became a test subject for such methodical destruction.

Picasso, a fiercely proud Spaniard living in Paris at the time, had already accepted a commission from the Spanish Republican government. His task? To create a mural for the Spanish Pavilion at the 1937 Paris International Exposition, a platform meant to showcase Spanish culture and appeal for international support. Picasso initially struggled with the theme, considering more abstract or celebratory Spanish motifs. The Republican government, hoping for a work that would highlight Spain's rich cultural heritage or inspire national pride, had given him broad creative freedom. He sketched various ideas: a bullfight, a reclining nude, even a painter in his studio. But none of these resonated with the urgent political climate, and he reportedly felt a growing dissatisfaction with these conventional themes. It was as if the canvas itself was waiting for a greater, more profound truth to be unleashed, a truth that personal musings couldn't quite capture. This initial struggle, to me, highlights the profound responsibility artists often feel when confronted with monumental historical events; how do you give voice to the unspeakable without trivializing it? It speaks to the immense pressure of finding a form adequate to such profound suffering, a challenge I imagine every artist grapples with at some point. But the news from Guernica shattered his artistic indecision, instantly providing him with an urgent, undeniable subject that transcended national pride to become a universal lament. The bombing transformed his commission into a moral imperative, making the canvas a battleground for human dignity. It became his personal crusade on canvas, a way to fight back against the brutality with the only weapon he truly wielded: his art. When news of the brutal, unprovoked bombing of Guernica reached him, his artistic purpose shifted dramatically. His commission transformed from a general statement into an immediate, visceral outcry against unimaginable cruelty. He didn't just paint a picture; he painted a manifesto against brutality, a visual scream of indignation. It’s a powerful example of how abstract art can reflect and respond to the most profound and horrific moments of human history, becoming a timeless symbol of resistance. Sometimes, realism just isn't enough to convey the sheer magnitude of emotional or psychological devastation. Abstract art, with its capacity to fragment, distort, and evoke rather than simply illustrate, can tap into a deeper, more primal understanding of suffering, allowing viewers to connect on a more fundamental, visceral level. Guernica stands as a towering testament to this power, proving that an artist can distill immense tragedy into a universal visual language. The urgency of his response was remarkable; fueled by outrage, Picasso threw himself into the work, completing the colossal mural in a furious burst of creativity over a mere 35 days. It's almost as if the atrocity itself infused his brushstrokes with a terrifying energy, compelling him to create a monument not of victory, but of visceral, unyielding pain. Imagine him in his vast Parisian studio on Rue des Grands Augustins, day and night, grappling with this immense canvas. He reportedly used industrial paints, common house painter's brushes, and whatever else he could get his hands on, literally attacking the surface with the raw force of his indignation. It wasn't just painting; it was an exorcism of grief and fury, a desperate attempt to transmute horror into a timeless warning. He was, in his own way, fighting back with every stroke. And frankly, I find that incredibly inspiring; the idea that one person, armed with a brush and a canvas, could channel such raw indignation into something so enduringly powerful.

Decoding the Chaos: Key Symbols and My Interpretations

Okay, so you’re looking at it, trying to make sense of the visual cacophony. All those distorted figures, some human, some animal, caught in a terrifying tableau. What’s truly going on beneath the surface? For me, it’s not about finding one definitive, 'Picasso-approved' answer for each symbol – he himself was famously evasive, once stating it was up to the viewer to interpret. He believed that the power of art lay in its ability to spark personal connection and contemplation, rather than deliver a prescriptive message. He didn't want to dictate meaning, but rather to provoke thought and feeling, allowing the painting to resonate differently with each individual, an approach that frankly, I admire. It's a language woven from the threads of universal suffering, a primal scream understood across all barriers. But I have my thoughts, my gut reactions, my personal connections, which I believe is exactly what he intended. It’s a language woven from the threads of universal suffering, a primal scream understood across all barriers. Let's delve into these powerful emblems, knowing that their true meaning lies as much in our own reflections as in Picasso's original intent.

The Bull: Brutality, Spain, or Picasso Himself?

This one always gets me. The bull stands stoically on the left, an almost detached observer to the unfolding horror. Is it a symbol of traditional Spanish culture, historically associated with bullfighting and its raw, untamed power? Or perhaps it embodies the brutal, uncaring force of fascism itself, a force that crushes all in its path? Some art historians even venture to see it as a self-portrait of Picasso, the brooding artist bearing witness to the devastation. My personal leaning is towards it being a symbol of blind, brute, irrational force – perhaps even the Minotaur from his own mythology, or an unfeeling god observing human folly. For Picasso, the Minotaur was a recurring motif, a creature of savage power and tormented duality, often representing his own complex psyche and primal urges. In Guernica, this creature of myth, standing stoically amidst human carnage, amplifies the sense of detached, almost ancient, brutality that presides over the scene, an embodiment of the unthinking violence that consumes all. I've always been drawn to how artists weave personal mythologies into their work, and seeing the Minotaur here, so detached yet so potent, feels like Picasso grappling with the darker, more primal aspects of humanity, and perhaps, even himself. It's a reminder that even the most 'civilized' among us can harbor a capacity for immense destruction, a truth that can be uncomfortable to acknowledge. The Minotaur, a creature of savage power and tormented duality in Picasso's personal mythology, here embodies a primal, unthinking brutality that seems to preside over the entire horrific scene. Some even argue it represents the Spanish people themselves, strong and enduring despite the agony inflicted upon them, a stoic witness to their own torment. But for me, the bull's stoicism feels like a cold, unfeeling indifference, a primal force detached from human suffering, making its presence all the more unsettling. This indifference, almost an ancient quality, suggests forces beyond immediate human control, watching the tragedy unfold with an almost geological patience. Could it also represent the historical inertia, the silent, ancient forces that sometimes seem to watch human conflicts unfold with an almost geological patience, indifferent to the immediate tragedy? Whatever its precise meaning, it’s certainly not a comforting presence; its stillness in the midst of chaos is profoundly unnerving. It's that detached, almost ancient power that truly makes the bull a chilling presence, an almost geological witness to human folly. And honestly, it makes me reflect on the silent forces that sometimes seem to govern our world, indifferent to the human cries below.

The Horse: The Agony of the Innocent

Central to the composition, almost literally skewered by a jagged spear, is the horse, its mouth agape in a horrifying, silent scream. For me, this is undeniably the innocent populace, the suffering masses, caught in the crosshairs of a war they didn't ask for. It’s the nobility of life, the unsuspecting, brought to its knees by senseless violence. This isn't just a horse; it's the ultimate victim, a creature of grace reduced to pure anguish. Its palpable suffering is, for me, one of the most heartbreaking and direct elements of the entire painting, a vivid echo of the suffering animals Picasso often depicted in his anti-bullfighting series. This central figure encapsulates the raw, unadulterated pain of those caught in senseless conflict, a symbol that feels tragically familiar in any era marred by violence. The horse, usually a symbol of grace and strength, is here reduced to a screaming, agonizing mass, its body pierced and contorted. It's not just a horse; it's the innocent victim, the everyman, everywoman, and every child caught in the indiscriminate maw of war, a symbol of all those unsuspecting lives consumed by chaos. Its suffering is depicted with such raw intensity that it becomes the very face of voiceless anguish, a stark reminder of humanity's capacity to inflict suffering upon the most vulnerable, echoing the tragic figures in classical art that depict ultimate sacrifice and pathos. It’s the universal cry of the innocent, whether human or animal, caught in the inferno of man's inhumanity, a truly piercing visual that sticks with you. When I look at it, I can’t help but hear the echoes of every innocent caught in every conflict, a symphony of suffering that never truly fades, a visceral sound I imagine. And the spear, it’s not just physical; it's the piercing of dignity, of peace, of everything good. This central figure encapsulates the raw, unadulterated pain of those caught in senseless conflict, a symbol that feels tragically familiar in any era marred by violence. It’s almost as if Picasso takes the traditional heroic symbolism of the horse and brutally subverts it, transforming it into the ultimate emblem of victimhood, a creature designed for strength and freedom, now utterly broken by forces beyond its control. It speaks to a fundamental injustice that, for me, resonates with an almost unbearable clarity. It's a testament to the fact that in war, the innocent are always the first casualties, their dignity and peace pierced by forces beyond their control.

Weeping Women & Distorted Figures: Universal Suffering

Throughout the canvas, particularly on the right, you see women in various states of terror and grief. Each figure tells a story of profound loss. There’s the woman screaming to the sky, clutching her dead baby – an image that transcends time and culture in its raw agony, her hands clenched in a gesture of desperate, futile protection, a timeless Pietà. Another figure emerges from a burning building, arms outstretched in a desperate, futile gesture, her head thrown back in agony, her very breath a silent scream. Their faces are contorted, eyes wide with horror, tongues like daggers, almost a physical manifestation of their screams. This is where Picasso's Cubist language truly shines, fragmenting their forms not just aesthetically, but to express an unbearable psychological pain. Each broken line, each displaced feature, amplifies the agony, making their suffering almost physically present to the viewer. The feeling of a world splintering is so immediate, almost a visual metaphor for the psychological fragmentation and trauma, akin to what we now understand as PTSD, inflicted by such indiscriminate violence. It reminds me of other powerful expressions of grief and raw emotion in art, though perhaps less overtly Cubist, like a skull or a scream. This Cubist fragmentation isn't merely aesthetic; it's a profound psychological fracturing, mirroring the mental and emotional devastation of those enduring such horrors, a direct visual representation of a mind torn apart. If you're curious about how Picasso and others broke down forms to capture deeper truths, my guide on the ultimate guide to Cubism offers a fascinating dive. This Cubist fragmentation isn't merely aesthetic; it's a psychological fracturing, reflecting the mental and emotional devastation of those enduring such horrors. I've often thought about how we, as humans, try to process unimaginable horror, and these figures, for me, embody that desperate, primal struggle to make sense of a world gone utterly mad. It's a scream that needs no translation. If you're curious about how Picasso and others broke down forms to capture deeper truths, my guide on the ultimate guide to Cubism offers a fascinating dive. I've often thought about how we, as humans, try to process unimaginable horror, and these figures, for me, embody that desperate, primal struggle to make sense of a world gone utterly mad. It's a scream that needs no translation. These figures aren't just suffering; they are contorted, fragmented, their very bodies echoing the destruction of their world. It’s a visual representation of how violence doesn’t just break bones, it shatters souls, leaving behind an unbearable emotional landscape. This deliberate fragmentation, for me, also speaks to the way trauma shatters perception, making reality itself feel broken and incomprehensible. It's like watching a mind unravel, each brushstroke a shard of a shattered memory.

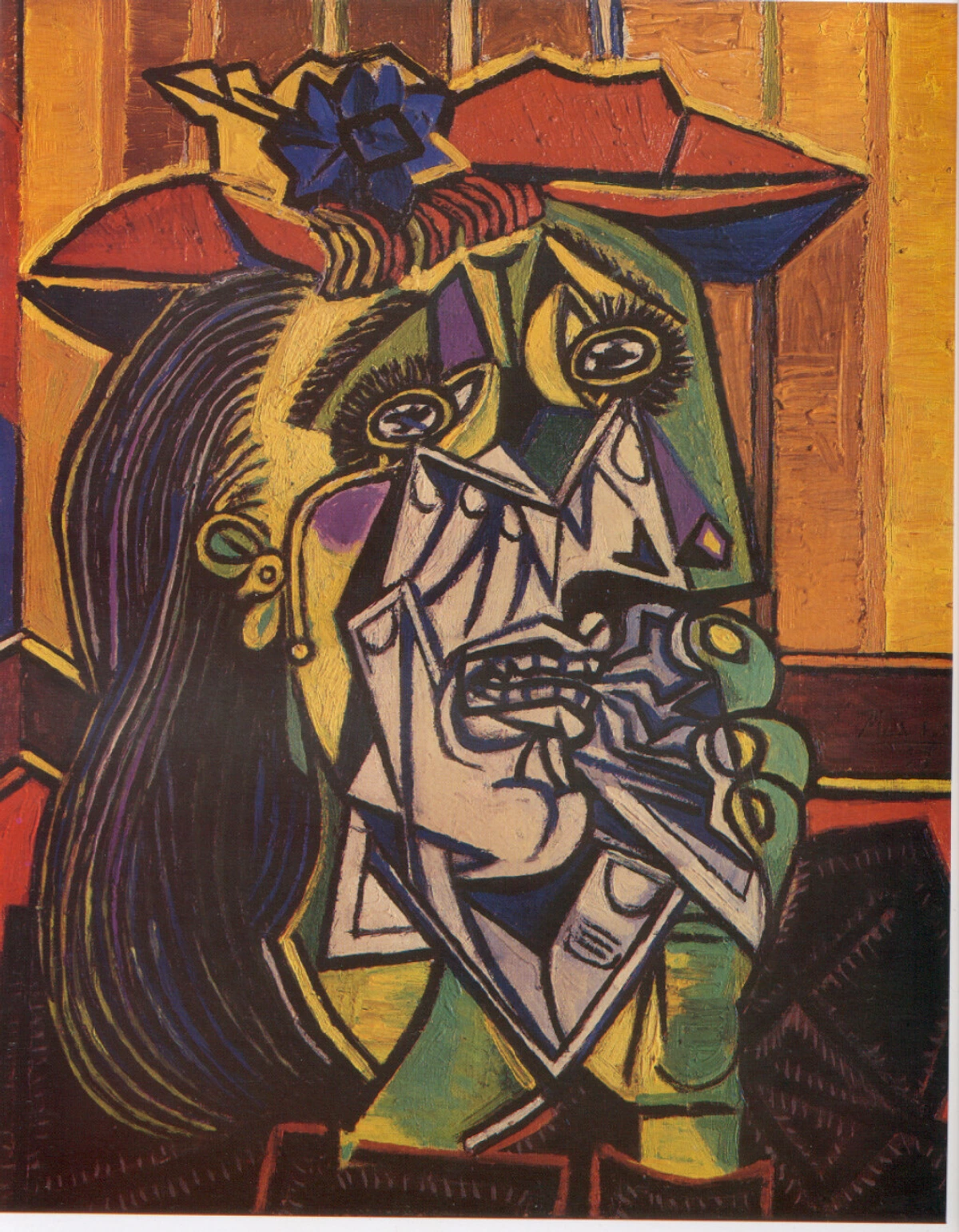

Perhaps one of the most famous individual crying figures from Picasso's related works is "The Weeping Woman" (1937), painted shortly after Guernica. While not directly in Guernica, it shares that profound sense of anguish and the fractured, Cubist representation of grief, almost like a close-up on the pain expressed in the larger mural. It's a testament to how deeply the bombing affected him, leading him to explore this universal emotion in multiple powerful forms.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/oddsock/101164507, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/

The Burning House: Collapse and Despair

Amidst the chaos, the collapsing structures and the figure emerging from the flames are potent symbols of the utter devastation wrought upon the town. The burning house isn't just a backdrop; it's an active participant in the tragedy, representing the destruction of homes, communities, and the very fabric of normal life. The sheer scale of the architectural collapse, the jagged edges of shattered stone and timber, speak to an irreversible loss, a world violently torn asunder. The figure trapped or escaping speaks to the desperate struggle for survival, the terror of being engulfed by war, and the loss of everything familiar. It's the collapse of a world, both literally and figuratively. The burning home is not just a physical ruin; it's the destruction of security, identity, and the very fabric of daily life, leaving behind only despair and displacement. If you're curious about this revolutionary style and how it evolved, I've got a whole guide on the ultimate guide to Cubism. The house, typically a symbol of safety, hearth, and home, is here consumed by an inferno, its very foundations giving way. This isn't just brick and mortar; it's the destruction of livelihood, memory, and community, a complete erasure of lives and histories. The figure emerging from the flames, arms outstretched, embodies the desperate struggle for survival, the terror of being engulfed by war, and the profound, irreplaceable loss of everything familiar. It's a stark visual metaphor for the complete societal breakdown that war imposes, leaving nothing but ashes and despair in its wake. This image, for me, also speaks to the profound homelessness and displacement that war creates, forcing people from their roots and leaving them adrift in a world shattered by conflict. It's a terrifying vision of what happens when the very foundations of society crumble under the weight of human-inflicted devastation.

The Ambiguity of the Door/Window: Escape or Entrapment?

Nestled within the chaotic composition, particularly on the right side of the canvas, are suggestions of doorways or windows, ambiguous openings that offer no clear path to escape. Are they avenues for potential rescue, or do they simply frame the horror, trapping the figures within? For me, these elements underscore the pervasive sense of entrapment and hopelessness that permeates Guernica. There's no clear exit, no safe haven from the unfolding tragedy, reinforcing the idea that the victims are caught in a nightmare from which there is no waking. The figures, with their desperate, outstretched arms, seem to search for an escape that never comes, amplifying the terror of being engulfed by war, and the profound, irreplaceable loss of everything familiar. It's the collapse of a world, both literally and figuratively. The burning home is not just a physical ruin; it's the destruction of security, identity, and the very fabric of daily life, leaving behind only despair and displacement. These ambiguous openings, rather than offering solace, seem to mock the victims, emphasizing the complete lack of sanctuary in a world consumed by violence. It’s a chilling detail that reinforces the painting's powerful message of entrapment and utter hopelessness. If you're curious about this revolutionary style and how it evolved, I've got a whole guide on the ultimate guide to Cubism. These false promises of escape are, for me, one of the most subtly cruel aspects of the painting, highlighting the utter inescapability of the horror.

https://heute-at-prod-images.imgix.net/2021/07/23/25b32e7b-0659-4b35-adfe-8895b41a5f89.jpeg?auto=format, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ It's a profound statement on the psychological prison of war, where even the hope of escape is a cruel illusion.

The Fallen Warrior: Broken Humanity

At the bottom of the canvas, a dismembered warrior lies, fragmented and broken, a testament to the devastating cost of conflict. He grasps a broken sword, clearly symbolizing the futility of traditional resistance against such overwhelming, mechanized force, highlighting how outdated methods stood no chance against modern aerial bombardment. But then there’s that small, almost overlooked flower, clutched delicately in a dead hand. What is it doing there? For me, it’s a tiny, stubborn flicker of hope, a poignant symbol of life’s enduring spirit, even amidst utter devastation. It’s a quiet, profound detail that speaks volumes about human resilience – the refusal to be completely extinguished, even when utterly broken. This tiny, almost imperceptible flower, clutched in the hand of the fallen, dismembered warrior, becomes a beacon. It's not a grand gesture, but a quiet, defiant whisper that even in the utter annihilation of war, the fragile spark of life, resilience, and indeed, hope, can persist. It suggests that while bodies may be broken and battles lost, the human spirit's capacity for renewal remains, a poignant detail in a scene of overwhelming tragedy, a stark contrast to the surrounding devastation. For me, it's Picasso's quiet insistence that humanity's spirit, though broken, can never be fully extinguished – a truly profound and affecting detail. It’s a stubborn, defiant little detail that, frankly, gives me a sliver of hope every time I see it, a testament to the enduring, almost unreasonable resilience of the human spirit even in the face of absolute devastation. And sometimes, isn't that tiny, unreasonable hope exactly what we need to cling to, like a desperate prayer whispered in the dark? It speaks to that indomitable human will to survive and find beauty, even when surrounded by the most unimaginable ugliness. It’s that profound contrast, the delicate flower against the brutal destruction, that, for me, elevates this symbol from mere detail to a central message of enduring humanity. It's a defiant act of life asserting itself in the face of absolute death.

The Light Bulb/Eye: A Harsh, Unblinking Truth

Above the suffering horse, a bare light bulb, starkly illuminated and shaped uncannily like an eye, casts down a harsh, unforgiving light. Is it a traditional symbol of an all-seeing God, observing silently but doing nothing? Or, more chillingly, does it represent the clinical, detached eye of the bomber, or even the unblinking eye of the world's media, bearing witness to atrocities? Some interpret it as a modern weapon, a bomb exploding, while others see it as the all-seeing eye of a detached observer – perhaps God, or perhaps the cold, technological gaze of modern warfare itself, unblinking as it surveys its devastation. For me, it functions as a brutal, almost documentary-style light, stripping away any romanticism of war, forcing us to confront the unvarnished, uncomfortable truth of the destruction. It's an exposing glare, akin to the unflinching eye of a camera lens, capturing atrocities for the record, ensuring no one can look away or deny the grim realities. This light, rather than illuminating a path to safety, simply highlights the horror, emphasizing the cold, calculating nature of modern conflict. I’ve always seen it as a brutal, almost documentary-style light, stripping away any pretense, forcing us to confront the unvarnished, uncomfortable truth of the destruction. It's not a comforting light; it's an exposing one, shining an uncomfortable glare on the realities of war. Some interpret it as a modern weapon, a bomb exploding, while others see it as the all-seeing eye of a detached observer – perhaps God, or perhaps the cold, technological gaze of modern warfare itself, unblinking as it surveys its devastation. There’s also the unnerving possibility it represents the impersonal 'eye' of propaganda, meticulously documenting its own terror, or even the harsh, uncompromising spotlight of truth that exposes all atrocities for what they are. For me, this detail is a chilling reminder of how easily information can be manipulated, or how the very act of witnessing can be weaponized. It makes you think about whose gaze is truly unbiased, and whose agenda is being served, a question that feels disturbingly relevant in our own media-saturated age. Could it be the eye of the future, witnessing the past, or even the unblinking lens of a documentary filmmaker capturing an unbearable reality? It’s a light that doesn't offer warmth or comfort, but rather a chilling clarity, forcing the viewer to confront the stark, inescapable realities of the atrocity. It's the ultimate 'truth lamp,' if you will, exposing every horror without mercy. This unsettling ambiguity of the light, shifting between witness, weapon, and truth-teller, ensures its power to disturb and provoke reflection endures. It’s a stark reminder that in times of conflict, truth itself can become a casualty, or a tool, depending on who is holding the lens.

The Mother and Dead Child: The Ultimate Devastation

To the far left, below the ominous bull, a mother wails in guttural anguish, clutching her dead child. This image, a direct and unmistakable reference to Christian iconography, specifically the Pietà (Mary cradling the dead Christ), is perhaps the most universally understandable and heart-wrenching symbol of the entire painting. It’s the ultimate devastation: the unthinkable loss of innocence, the pure, untainted grief of a parent whose world has been shattered. It transcends culture, religion, and time, hitting you right in the core of what it means to be human and to suffer. This motif, rooted in art history, is elevated here to a universal symbol of civilian casualties, a heartbreaking tableau that has unfortunately been replicated countless times throughout human history. The mother's guttural wail, her face contorted in a primal scream of anguish, resonates beyond any specific religious context. It’s the ultimate, unbearable grief of a parent witnessing the senseless loss of a child, a tragedy that transcends all boundaries and speaks directly to the deepest fears and sorrows of humanity. This isn't just a depiction; it's an empathy trigger, pulling you into the raw, untainted grief. It’s a scene that, for me, cuts deeper than any other, a stark reminder of the ultimate, irreversible cost of war: the crushing of innocence and the shattering of family, a wound that never truly heals. This powerful image continues to echo in countless conflicts, a tragic testament to its enduring relevance. It's an empathy trigger, pulling you into the raw, untainted grief of a universal tragedy, making it impossible to remain a detached observer. It's the kind of pain that feels almost too personal to witness, yet Picasso forces us to confront it.

The Dying Bird: A Muted Plea?

Look closely at the upper left section, just above the bull. Some interpreters identify a subtle, almost obscured bird-like figure, possibly impaled or dying, between the bull and the horse. If present, this bird, traditionally a symbol of freedom or peace, would represent yet another innocent victim, a muted plea for an end to the violence. Its ambiguous presence, however, leaves its interpretation open, perhaps suggesting that even these fragile symbols of hope are struggling to survive in the overwhelming darkness of war. It's a subtle note in a symphony of screams, but one that always catches my attention, a poignant symbol of lost innocence and a muted plea for an end to the violence. This particular figure, for me, embodies the very essence of human tragedy. The raw, gut-wrenching grief depicted is not specific to Guernica; it's a timeless, agonizing lament that resonates with anyone who has witnessed or imagined such unthinkable loss. And if I’m honest, that little dying bird, if it is truly there, is perhaps the most heartbreaking detail of all – a fragile, silent casualty of a world too consumed by its own brutality to notice the quiet song of peace fading away. It’s a tiny, almost overlooked detail that, once seen, becomes impossible to unsee, a poignant whisper of what is lost when humanity turns on itself. This elusive symbol, hovering at the edge of perception, underscores how easily peace can be extinguished and forgotten amidst the clamor of conflict. It's a quiet testament to the small, often unnoticed losses that accumulate in the vast tragedy of war.

Picasso's Style: Why Cubism for Such a Subject?

Why did Picasso choose such a fragmented, almost distorted style for Guernica? Well, think about what Cubism inherently does. It allows for multiple perspectives to be shown simultaneously, breaking down objects and figures into geometric shapes, capturing movement and time within a single frame. In Guernica, this isn't just an artistic exercise in breaking forms; it’s a profoundly powerful metaphorical tool. The fragmented forms don't just reflect the physical fragmentation of life; they embody the shattering of peace, the psychological trauma of war, and the moral breakdown of society. It's a visual echo of a world literally torn apart, forcing you to see the same horror from every conceivable angle at once. Think of it as a shattered mirror, each shard reflecting a piece of the unbearable truth, forcing you to piece together the full, devastating picture in your own mind. It’s a brilliant, unsettling way to communicate the disorientation and terror of being caught in such a maelstrom, a fractured reality mirroring fractured lives. It’s as if Picasso forces us to experience the psychological chaos and physical fragmentation of war through the very structure of the painting itself. This deliberate fragmentation, for me, also speaks to the way trauma shatters perception, making reality itself feel broken and incomprehensible. It's a visual language perfectly suited to articulating the unspeakable horrors of indiscriminate violence. This unique approach, using aesthetic principles to convey psychological states, is what truly makes Cubism in Guernica more than just a style; it's a profound statement on the human condition under duress. It's a visual language perfectly suited to articulating the unspeakable horrors of indiscriminate violence, a language that speaks directly to the fractured experience of trauma.

He didn't want to depict a realistic battle scene with soldiers and bombs, which might have felt too specific or even glorifying. Instead, he wanted to convey the raw feeling of terror, the universal experience of being shattered, the psychological impact of such overwhelming violence. The monochrome palette of greys, blacks, and whites, reminiscent of urgent newspaper photographs and propaganda posters, also lends a stark, journalistic immediacy to the tragedy. This deliberate choice of a grisaille palette strips away any aesthetic distraction of color, forcing you to confront the grim reality of the subject matter directly, pulling you in and demanding your witness, much like a harrowing photograph of a horrific event would. It detaches the horror from specific national colors or flags, elevating it to a universal human experience of despair. By removing color, Picasso ensures that the focus remains solely on form, emotion, and the stark message. It amplifies the gravity and seriousness of the message, making it feel timeless and universal, detached from the specific hues of any particular flag or national identity. I've always felt it gives the painting a kind of brutal honesty, like a searing documentary that refuses to let you look away. It makes the suffering feel incredibly real, immediate, and utterly inescapable, stripping away any romanticism war might once have held. It strips away any distraction of color, forcing you to confront the grim reality, pulling you in and demanding your witness, much like a harrowing photograph of a horrific event would. This isn't just a stylistic choice; it's a moral one, connecting the painting to the immediate, unvarnished truth of reported atrocities. If you're curious about this powerful, often understated technique, my guide on what is grisaille: understanding the monochromatic painting technique offers more insight. This choice, for me, makes the tragedy feel less like a 'historical' event and more like a raw, ongoing wound, stripping it of any potential for glorification and hammering home the universal cost of conflict. It’s a deliberate artistic decision that reinforces the grim, journalistic nature of the piece, turning the canvas into a searing report from the front lines of human suffering. It's a truly unflinching gaze at the darkest aspects of humanity.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/wallyg/2384266076, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.0/

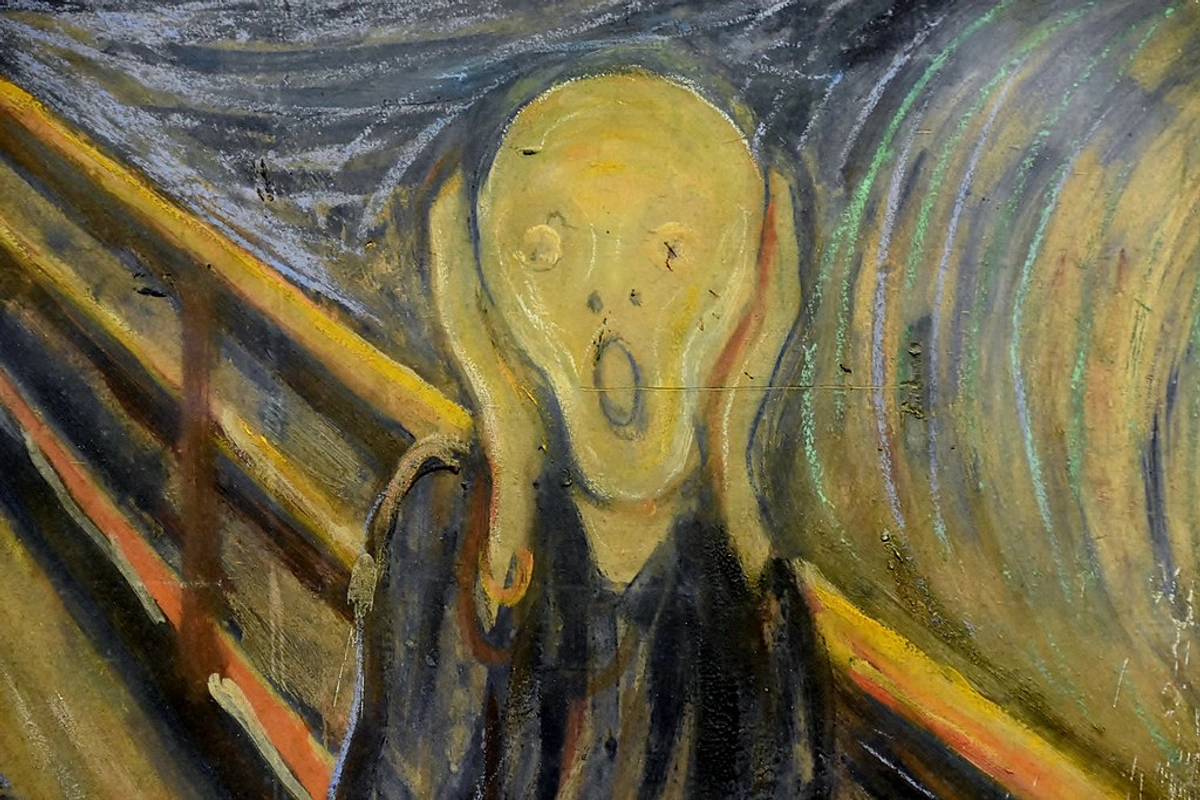

This isn't just Cubism; it's Cubism infused with a raw, almost agonizing Expressionist emotionality, making it an incredibly potent statement that speaks directly to the soul. Picasso masterfully combined the intellectual dissection of Cubism with the intense subjective emotionality of Expressionism, creating a visual language of suffering that is both analytical and deeply felt.

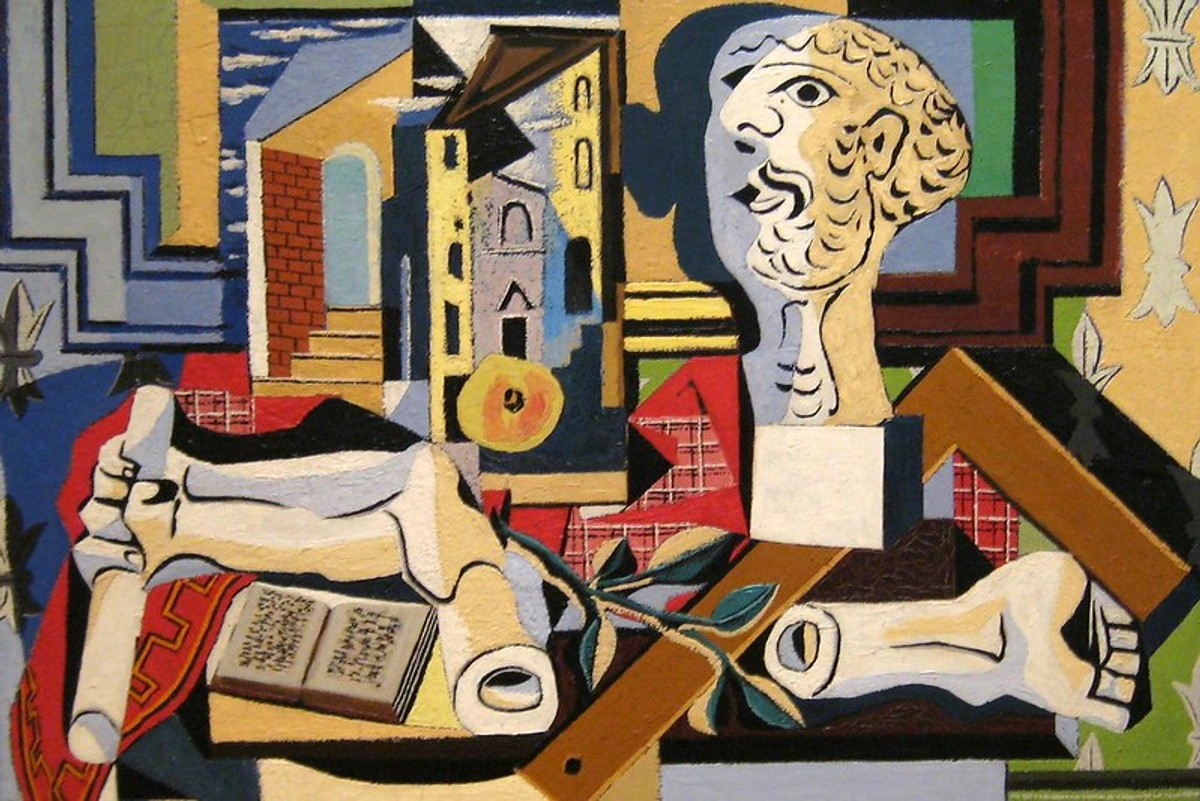

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Edvard_Munch,_The_Scream,_1893,National_Gallery,Oslo%281%29%2835658212823%29.jpg, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 This wasn't a sudden departure; Picasso, like many artists, drew from a rich tapestry of influences. One might even see echoes of Francisco Goya's stark depictions of war atrocities in his 'Disasters of War' series, which similarly conveyed unvarnished human suffering without romanticism, predating the Expressionist movement by decades but capturing its raw spirit. Guernica, then, stands as a testament to the power of artistic movements to convey profound human experience, a theme I often explore in my own work when I create art to sell, trying to express something authentic. If you're interested in how artists harness raw emotion, you might also like my guide on the ultimate guide to Expressionism. It's a testament to the power of artistic movements to convey profound human experience, a theme I often explore in my own work when I create art to sell, trying to express something authentic. If you're interested in how artists harness raw emotion, you might also like my guide on the ultimate guide to Expressionism. It's a fusion that, I believe, allows the painting to hit you both intellectually and emotionally, a one-two punch that leaves an indelible mark. This powerful combination of intellectual rigor and raw emotion is what makes Guernica so utterly unforgettable. It’s a painting that doesn't just ask you to think; it demands that you feel, deeply and uncomfortably.

https://images.zenmuseum.com/art/328/scan.jpeg, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.0/

This powerful combination of intellectual rigor and raw emotion is what makes Guernica so utterly unforgettable. It’s a painting that doesn't just ask you to think; it demands that you feel, deeply and uncomfortably.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/vintage_illustration/51913390730, [https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/]

Goya's Echoes: A Precedent for War's Horrors

While Guernica is undeniably a modernist masterpiece, it carries the echoes of earlier Spanish masters who similarly confronted the brutality of conflict. I often think of Francisco Goya, especially his 'Disasters of War' series, created over a century before Picasso. Goya's unflinching engravings depicted the atrocities of the Peninsular War with a raw, visceral realism that shocked his contemporaries and continues to disturb us today. Like Picasso, Goya didn't romanticize war; he exposed its grotesque realities and the profound suffering it inflicted on innocent civilians. There’s a direct lineage, I believe, in that unvarnished, almost journalistic approach to depicting man's inhumanity to man. Both artists, across different eras and styles, used their immense talent to bear witness and to scream against the barbarity. Goya's prints, like 'The Third of May 1808,' depicting French soldiers executing Spanish civilians, or 'Disasters of War' series with its chilling scenes of rape, mutilation, and starvation, share Guernica's refusal to glorify conflict. Instead, they strip away all pretense, revealing the brutal, dehumanizing impact of war on ordinary people, a stark reality that resonates across centuries and speaks to a recurring human tragedy. It's almost as if Goya set the stage for Picasso, preparing the artistic conscience for an even louder, more fragmented scream against injustice. This connection, for me, deepens the tragic understanding of Guernica, placing it within a long and painful history of artists who dared to confront the darkness of human nature. Goya's raw, unflinching approach paved the way for Picasso's modernist lament, proving that certain truths about humanity's darker side are timeless, requiring constant artistic re-interrogation. It's a sobering thought that the themes of 'The Disasters of War' remain tragically relevant, echoing in today's conflicts.

While Guernica is undeniably a modernist masterpiece, it carries the echoes of earlier Spanish masters who similarly confronted the brutality of conflict. I often think of Francisco Goya, especially his 'Disasters of War' series, created over a century before Picasso. Goya's unflinching engravings depicted the atrocities of the Peninsular War with a raw, visceral realism that shocked his contemporaries and continues to disturb us today. Like Picasso, Goya didn't romanticize war; he exposed its grotesque realities and the profound suffering it inflicted on innocent civilians. There’s a direct lineage, I believe, in that unvarnished, almost journalistic approach to depicting man's inhumanity to man. Both artists, across different eras and styles, used their immense talent to bear witness and to scream against the barbarity. Goya's prints, like 'The Third of May 1808,' depicting French soldiers executing Spanish civilians, or 'Disasters of War' series with its chilling scenes of rape, mutilation, and starvation, share Guernica's refusal to glorify conflict. Instead, they strip away all pretense, revealing the brutal, dehumanizing impact of war on ordinary people, a stark reality that resonates across centuries and speaks to a recurring human tragedy. It's almost as if Goya set the stage for Picasso, preparing the artistic conscience for an even louder, more fragmented scream against injustice.

Beyond the Canvas: Cubism, Expressionism, and Their Legacy

It’s fascinating to consider how these movements, Cubism's analytical fragmentation and Expressionism's raw emotionality, provided Picasso with the perfect vocabulary for Guernica. Other artists, too, have merged styles to deliver potent social commentary. Think of the German Expressionists, who used distorted figures and intense colors to critique societal ills after World War I, or even artists today who blend digital techniques with traditional forms to address contemporary injustices. Guernica stands as a powerful testament to art's capacity to transcend stylistic boundaries in service of a profound human message. This fusion of intellectual rigor and raw emotionality isn't unique to Picasso, though he mastered it. Think of the German Expressionists like Ernst Ludwig Kirchner or Otto Dix, who, scarred by World War I, used distorted figures and jarring colors to condemn the horrors they witnessed and critique their society's failings. Or consider even contemporary artists who, using digital tools or mixed media, blend forms and styles to comment on current global conflicts or social injustices. The lesson is clear: when art speaks to fundamental human truths, it often finds its most potent voice by breaking free from rigid categories, by refusing to be easily categorized or consumed. It’s about forging a new language when the old ones fail to express the unspeakable. Think of how artists today might use street art or digital installations to comment on refugee crises or human rights abuses, drawing a direct lineage from Picasso's powerful visual manifesto. This ongoing legacy reminds us that art remains a vital tool for social commentary across generations and technologies. And this, for me, is the true power of this section: to recognize that some truths are so immense, so devastating, that they demand a new way of seeing, a new way of feeling, and a new way of telling. It’s a profound reminder that the most impactful art often defies easy classification, choosing instead to serve the urgent message it carries. It's about finding the right artistic language to articulate the unspeakable.

It’s fascinating to consider how these movements, Cubism's analytical fragmentation and Expressionism's raw emotionality, provided Picasso with the perfect vocabulary for Guernica. Other artists, too, have merged styles to deliver potent social commentary. Think of the German Expressionists, who used distorted figures and intense colors to critique societal ills after World War I, or even artists today who blend digital techniques with traditional forms to address contemporary injustices. Guernica stands as a powerful testament to art's capacity to transcend stylistic boundaries in service of a profound human message. This fusion of intellectual rigor and raw emotionality isn't unique to Picasso, though he mastered it. Think of the German Expressionists like Ernst Ludwig Kirchner or Otto Dix, who, scarred by World War I, used distorted figures and jarring colors to condemn the horrors they witnessed and critique their society's failings. Or consider even contemporary artists who, using digital tools or mixed media, blend forms and styles to comment on current global conflicts or social injustices. The lesson is clear: when art speaks to fundamental human truths, it often finds its most potent voice by breaking free from rigid categories, by refusing to be easily categorized or consumed. It’s about forging a new language when the old ones fail to express the unspeakable.

Picasso's Political Conscience: More Than Just Guernica

While Guernica is undeniably his most famous political statement, Picasso's engagement with social and political issues wasn't a one-off. Throughout his long career, his art often reflected the turmoil of his times and his deeply held convictions. From his early "Blue Period" works, such as 'The Absinthe Drinker' or 'The Old Guitarist,' which depicted the struggles of the poor and marginalized, highlighting the harsh realities of poverty and despair, to his anti-Franco stance during the Spanish Civil War and beyond, and even works like 'Massacre in Korea' (1951) which echoed Guernica's anti-war sentiment in a Cold War context, Picasso used his art as a powerful vehicle for social commentary.

https://leelibrary.librarymarket.com/event/pablo-picasso-his-life-and-times-85968, http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/us/ You see it even in his "Rose Period," where themes of melancholy and vulnerability often subtly underpinned the more romantic subjects, revealing a deep empathy for the human condition, even amidst the apparent lightness. His involvement even extended to joining the French Communist Party in 1944, a clear demonstration of his lifelong commitment to social justice and his hope for a more egalitarian world, a decision that carried significant weight during the Cold War era. He famously declared, "What do you think an artist is? An imbecile who has only eyes if he is a painter...? On the contrary, he is at the same time a political being, constantly aware of the heartbreaking, passionate, or delightful things that happen in the world, shaping himself completely in their image." This wasn't a casual observation; it was a profound declaration of artistic responsibility, asserting that true art cannot exist in a vacuum, detached from the human condition and the political realities shaping it. Guernica was the culmination of this lifelong commitment, making him not just an artistic genius, but also a profound moral voice. It’s a statement that, for me, resonates deeply, a reminder that art can and should be a powerful force for change, not just decoration, and that artists bear a unique responsibility to bear witness and speak truth. And truly, isn't that what we hope for from our greatest creators – not just beauty, but truth, even when that truth is horrifying? He also created other powerful anti-war works like 'Massacre in Korea' (1951), which echoed Guernica's sentiment in a Cold War context, and the monumental 'War and Peace' (1952) murals, further solidifying his unwavering dedication to these themes throughout his career. This consistent engagement with human suffering and political injustice, for me, elevates him beyond a mere artist to a vital chronicler and conscience of the 20th century. If you’re curious about his full artistic journey, from his early periods to his later masterpieces, my ultimate guide to Picasso offers a comprehensive dive. He wasn't afraid to use his art as a weapon against injustice, a true testament to the power of artistic conviction.

My Guernica Moment: Why it Still Resonates Today

Walking away from Guernica, I always feel a profound sadness, a heavy weight in my chest, but also a fierce admiration for Picasso's courage and his unwavering artistic conviction. He took an unspeakable act of violence, a crime against humanity, and transmuted it into a universal cry for peace, a monument to human suffering. It’s emphatically not a comfortable painting, and it’s not meant to be. It forces us to look, to truly feel, and perhaps most importantly, to remember. And that, for me, is its enduring, undeniable meaning.

In a world still plagued by conflict, by bombings and displacement, Guernica remains shockingly, tragically relevant. It’s a permanent, searing reminder of the devastating human cost of war, a message that, frankly, we seem to need to hear again and again, tattooed into our collective consciousness. It speaks to the brutal realities of today's headlines—from urban warfare in places like Ukraine or Gaza, the devastating refugee crises spanning continents, from indiscriminate bombings targeting civilians to the silencing of dissent in authoritarian regimes, and even the unsettling rise of misinformation that distorts truth—just as powerfully as it did to those of 1937. It's a timeless scream against the barbarity that humans inflict upon each other, a chilling premonition of endless conflict. Sadly, its message seems to be one we are continually forced to relearn, generation after generation, a cyclical nightmare that art relentlessly reminds us of. It’s a painful but necessary truth, this enduring relevance, almost a prophecy of continued human conflict. It makes me reflect on my own artistic journey and timeline, how different artists are shaped by the world around them, and how art can truly serve as a mirror, a stark warning, and a hopeful beacon against the darkness, pushing us not just to remember, but to act and to continually strive for a world where such a scream is never again necessary. This monumental work doesn't just ask us to remember; it compels us to act, to understand, and to constantly question the forces that lead to such unimaginable suffering, pushing us to challenge indifference and complacency. Its enduring meaning, for me, is a profound and urgent call to conscience—a challenge to each of us. This enduring relevance, tragic as it is, speaks to a deeply unsettling truth: the capacity for human cruelty, and the suffering it inflicts, remains a constant, recurring nightmare across generations and geographies. It makes me reflect on my own artistic journey and timeline, how different artists are shaped by the world around them, and how art can truly serve as a mirror, a stark warning, and a hopeful beacon against the darkness, pushing us not just to remember, but to act and to continually strive for a world where such a scream is never again necessary. It's a raw nerve, exposed for all to see, and it demands a response. And honestly, isn't that the most vital thing art can do: provoke, challenge, and demand that we never truly look away?

The Making of a Masterpiece: Picasso's Process

It’s almost unfathomable to think that this colossal, emotionally charged work was conceived and completed in just 35 days. Picasso attacked the canvas with an almost frenzied intensity, working tirelessly, often at night. We know much about its evolution thanks to the remarkable photographic documentation by his lover and fellow artist, Dora Maar. Her black-and-white photographs captured Guernica’s various stages, revealing how Picasso incorporated, rejected, and refined motifs, slowly building the complex narrative of suffering you see today. Watching the painting evolve through her lens, you get a palpable sense of his iterative process, his struggle to find the perfect visual language for such an unspeakable tragedy. Each sketch, each alteration, was a step deeper into the heart of the horror. Dora Maar's invaluable photographic record not only provides a unique insight into the artistic process but also serves as a poignant document of Picasso's emotional journey as he grappled with such a weighty subject. Maar herself was a formidable surrealist photographer and painter, a keen observer with a sharp, independent artistic vision, and Picasso's lover and muse during this intensely creative period. Her photographic series of Guernica in progress offers us a rare, intimate window into the crucible of creation, showing her own artistic eye at work, not just documenting, but interpreting the unfolding drama on the canvas, almost as a co-conspirator in its birth. Her surrealist sensibilities, I think, made her uniquely attuned to the fragmented and emotionally charged nature of Picasso's work on Guernica. Her images, for example, show the bull's head initially placed differently, its form shifting from more benevolent to a starker symbol of brute force, or the horse's agony refined through multiple studies, its tormented head becoming more piercing with each iteration. These photographs provide us with an almost forensic look into the birth of a masterpiece born from outrage. It's truly a rare glimpse into the intense communion between artist and subject, and a powerful testament to the iterative nature of profound creation. Her images show not just the evolution of the painting, but also the physical and emotional intensity of Picasso's engagement with the canvas, transforming the act of creation into a performance of anguish and determination. Working in his vast Parisian studio, Picasso attacked the colossal canvas with a frenzied, almost obsessive energy. He would often work through the night, fueled by indignation and a furious need to express the unspeakable. He famously used a range of tools, from traditional brushes to common house painting tools, attacking the canvas with raw force. Maar's photographs capture him in various states of intense focus, showing how he literally wrestled with the painting, adjusting figures, erasing sections, and layering new forms, as if the canvas itself were a living entity mirroring his internal turmoil and the chaos he sought to depict.

Picasso's Unfinished Sketches: A Glimpse into the Mind of a Master

It’s truly fascinating to look at Picasso's preparatory sketches for Guernica. They aren't just technical exercises; they are raw explorations of emotion and form, revealing his intense intellectual and emotional engagement with the subject. You see him experimenting with different compositions, refining the anguished expressions of the figures, and wrestling with the symbolism of the bull and the horse. These sketches, which often show multiple variations of the same motif, underscore the deliberate, yet feverish, nature of his creative process. They are, in a way, tiny screams before the monumental roar, a testament to the depth of his commitment to capturing the profound tragedy. You can see him grappling with the emotional weight, experimenting with the precise angle of a weeping eye or the contortion of a screaming mouth, each line a whisper of the final, thunderous outcry. It's almost like watching a sculptor chip away at stone, not to reveal a figure, but to excavate an emotion. These sketches, for me, aren't just preliminary studies; they are a raw, unfiltered journey into the mind of a genius grappling with unspeakable horror, trying to find the perfect visual language for a universal scream. They reveal the sheer intellectual and emotional labor involved in creating such a powerful work, showing how every detail, every line, was meticulously considered and imbued with meaning.

It’s almost unfathomable to think that this colossal, emotionally charged work was conceived and completed in just 35 days. Picasso attacked the canvas with an almost frenzied intensity, working tirelessly, often at night. We know much about its evolution thanks to the remarkable photographic documentation by his lover and fellow artist, Dora Maar. Her black-and-white photographs captured Guernica’s various stages, revealing how Picasso incorporated, rejected, and refined motifs, slowly building the complex narrative of suffering you see today. Watching the painting evolve through her lens, you get a palpable sense of his iterative process, his struggle to find the perfect visual language for such an unspeakable tragedy. Each sketch, each alteration, was a step deeper into the heart of the horror. Dora Maar's invaluable photographic record not only provides a unique insight into the artistic process but also serves as a poignant document of Picasso's emotional journey as he grappled with such a weighty subject. Maar herself was a formidable surrealist photographer and painter, a keen observer, and Picasso's lover and muse during this intensely creative period. Her photographic series of Guernica in progress offers us a rare, intimate window into the crucible of creation, showing her own artistic eye at work, not just documenting, but interpreting the unfolding drama on the canvas, almost as a co-conspirator in its birth. Her images, for example, show the bull's head initially placed differently, or the horse's agony refined through multiple studies, providing us with an almost forensic look into the birth of a masterpiece born from outrage. It's truly a rare glimpse into the intense communion between artist and subject. Dora Maar, herself a formidable surrealist photographer and Picasso’s lover during this intense period, captured over 40 photographs of the work in progress. These aren't just snapshots; they're a visual diary of creation, an intimate look at how a masterpiece is wrestled into existence, documenting every scrape, every stroke, every change of heart. Without her keen eye, much of our understanding of Guernica's genesis would be lost, and that’s a thought that always gives me pause. Working in his vast Parisian studio, Picasso attacked the colossal canvas with a frenzied, almost obsessive energy. He would often work through the night, fueled by indignation and a furious need to express the unspeakable. He famously used a range of tools, from traditional brushes to common house painting tools, even household paint, attacking the canvas with raw force. Maar's photographs capture him in various states of intense focus, showing how he literally wrestled with the painting, adjusting figures, erasing sections, and layering new forms, as if the canvas itself were a living entity mirroring his internal turmoil and the chaos he sought to depict. Her unique perspective as both an artist and an intimate observer adds another layer to our understanding of Guernica's profound genesis, allowing us to bear witness to the raw emotional and intellectual labor of its creation. Her unique perspective as both an artist and an intimate observer adds another layer to our understanding of Guernica's profound genesis, allowing us to bear witness to the raw emotional and intellectual labor of its creation. Her images show not just the evolution of the painting, but also the physical and emotional intensity of Picasso's engagement with the canvas, transforming the act of creation into a performance of anguish and determination. Dora Maar, herself a formidable surrealist photographer and Picasso’s lover during this intense period, captured over 40 photographs of the work in progress. These aren't just snapshots; they're a visual diary of creation, an intimate look at how a masterpiece is wrestled into existence, documenting every scrape, every stroke, every change of heart. Without her keen eye, much of our understanding of Guernica's genesis would be lost, and that’s a thought that always gives me pause. Working in his vast Parisian studio, Picasso attacked the colossal canvas with a frenzied, almost obsessive energy. He would often work through the night, fueled by indignation and a furious need to express the unspeakable. He famously used a range of tools, from traditional brushes to common house painting tools, even household paint, attacking the canvas with raw force. Maar's photographs capture him in various states of intense focus, showing how he literally wrestled with the painting, adjusting figures, erasing sections, and layering new forms, as if the canvas itself were a living entity mirroring his internal turmoil and the chaos he sought to depict.

Global Impact & Enduring Relevance

The Exhibition at the Paris Exposition (1937)

The Spanish Pavilion at the 1937 Paris International Exposition was conceived as a bold statement by the embattled Republican government, a platform to showcase Spanish culture and rally international support against fascism. The pavilion itself, a minimalist, glass-and-steel structure designed by Spanish architects Josep Lluís Sert and Luis Lacasa, embraced a stark, modern aesthetic. This was a deliberate and powerful contrast to the grandiose, neoclassical fascist pavilions of Germany and the Soviet Union, visually asserting the Republican government's commitment to modernity and progressive ideals. Guernica, displayed prominently, was the undisputed centerpiece, a monumental cry that immediately captured attention. It hung alongside other powerful works by Spanish artists like Joan Miró and Alexander Calder, but Picasso’s mural, with its stark message, stood out, drawing crowds and sparking intense discussion. Its raw depiction of suffering served as a powerful counter-narrative to the fascist propaganda that also permeated the Exposition, making an undeniable political statement on the world stage, sparking both awe and discomfort among its international viewers. It truly was, I think, a masterstroke of political and artistic defiance, a silent but thunderous rebuke to the celebration of power and might presented by other nations. The pavilion, and Guernica within it, acted as a visual manifesto for a democratic Spain under siege, a place where art was explicitly used as a tool for political advocacy and a plea for humanity. It was a bold declaration that art could be a powerful weapon in the fight for freedom and democracy.

The Spanish Pavilion at the 1937 Paris International Exposition was conceived as a bold statement by the embattled Republican government, a platform to showcase Spanish culture and rally international support against fascism. The pavilion itself, a minimalist, glass-and-steel structure designed by Spanish architects Josep Lluís Sert and Luis Lacasa, embraced a stark, modern aesthetic. This was a deliberate and powerful contrast to the grandiose, neoclassical fascist pavilions of Germany and the Soviet Union, visually asserting the Republican government's commitment to modernity and progressive ideals. Guernica, displayed prominently, was the undisputed centerpiece, a monumental cry that immediately captured attention. It hung alongside other powerful works by Spanish artists like Joan Miró and Alexander Calder, but Picasso’s mural, with its stark message, stood out, drawing crowds and sparking intense discussion. Its raw depiction of suffering served as a powerful counter-narrative to the fascist propaganda that also permeated the Exposition, making an undeniable political statement on the world stage, sparking both awe and discomfort among its international viewers. It truly was, I think, a masterstroke of political and artistic defiance, a silent but thunderous rebuke to the celebration of power and might presented by other nations. The pavilion, and Guernica within it, acted as a visual manifesto for a democratic Spain under siege.

The Global Journey: A Symbol on Tour