The Unseen Loom: How African Textiles Wove Their Way into Modern & Contemporary Abstract Art

Sometimes, I find myself staring at a painting, completely lost in its lines and colors, and I feel like I'm peering into a secret conversation between artists across centuries and continents. It's a humbling thought, really, to consider how much art, even the most 'original' and 'avant-garde,' is built upon a foundation of shared human experience and inspiration. And if you're anything like me, you probably love unearthing those hidden connections, those subtle whispers of influence that transform how we see a familiar piece. Today, I want to pull back the curtain on one of my absolute favorite, often-understated, influences on modern abstract art: the profound and undeniable impact of African textiles. This isn't just a story of aesthetics; it's a tale of philosophy, community, and the surprising ways old wisdom reshapes the new. I often wonder what stories these threads still whisper to us today, echoing in the contemporary forms we create.

More Than Fabric: Weaving Stories, Inspiring Abstraction

Before we dive into the 'how,' let's truly grasp the 'why.' What is it about textiles, particularly those from diverse African cultures, that so deeply captivated the minds of early 20th-century European modernists? Well, if you ask me, it's because textiles are, at their heart, storytelling in its purest, most tangible form. They're history, identity, philosophy, and emotion woven into existence. They're functional, yes, but also deeply symbolic, often created through communal efforts that valued collective expression over individual celebrity. It’s like a complex emotion conveyed not just by words, but by the rhythm of breath, the unspoken pauses, the very texture of interaction. African textiles speak this visual language, rich with rhythm, repetition, and a captivating abstract syntax – a complex system of visual rules that communicate deep meaning without a single spoken word.

This 'syntax' isn't a written language, of course, but a sophisticated system of visual rules – principles of rhythmic repetition, modularity, non-representational forms, and inherent symbolic meaning. Modern European artists, feeling constrained by traditional academic art, were searching for new ways to express the rapidly changing world around them. They sought authenticity, raw emotion, and a departure from strict representationalism. But deeper than that, they discovered a philosophical alternative: a way of seeing that valued the collective spirit of creation over individual genius, a stark contrast to Western artistic traditions. In many African cultures, art wasn't just about individual expression; it was interwoven with daily life, spiritual practices, and social structures, often created anonymously for communal benefit, where the process and shared meaning mattered more than the isolated artist. This shift from the individual creator to a communal narrative was, in my opinion, a profound turning point.

In African textiles, they found a rich vocabulary of geometric shapes and symbolism, bold uses of color harmony, and an intrinsic connection between form and meaning that was both ancient and startlingly 'modern' in its abstract qualities. These were also often functional objects, blurring the lines between art and utility in a way Western art had largely forgotten.

Consider, for instance, the intricate geometric patterns of Kuba cloth from the Democratic Republic of Congo, known for its complex interweaving of raffia fibers and symbolic motifs achieved through a unique cut-pile appliqué technique. These motifs don't just decorate; they communicate proverbs, historical events, and status. A specific pattern might, for example, denote royal lineage or a significant victory. Or the vibrant, symbolic motifs of Kente cloth from Ghana, meticulously woven in long, narrow strips which are then stitched together to create larger, often asymmetrical designs. Each color and pattern holds specific meanings, often reserved for royalty and significant ceremonies – imagine the deep gold representing wealth, or green for fertility, each woven into an intentional narrative. And then there's Bogolanfini, or mud cloth, from Mali, with its striking graphic patterns created through a resist-dyeing process using fermented mud. This isn't a mere dye; it's a living canvas where specific earth elements are strategically applied and removed, revealing stark, symbolic designs. Beyond these, we find the deep indigo patterns of Adire cloth from Nigeria, made through resist-dyeing using cassava paste, creating intricate designs on cotton fabric, or the vibrant beadwork of the Ndebele people, whose geometric designs adorn not just textiles but also homes, communicating identity and social status. These aren't merely decorative; they convey status, proverbs, historical events, philosophical concepts, and even entire worldviews. For an artist like me, who often thinks in layers and textures to build narrative in my own abstract art prints and paintings, the idea of a textile as a layered, textured narrative — and a deeply philosophical one — is incredibly appealing.

The Handmade Aesthetic: A Counterpoint to Industrialization and a Search for Authenticity

Beyond the profound visual language, there was the undeniable allure of the handmade. In an era increasingly dominated by industrialization, African textiles, with their subtle imperfections, unique variations, and tactile qualities, offered a potent antidote – a raw, authentic connection to human touch and tradition. Modernists, feeling disillusioned by the perceived sterility of mass production and the rigid academic traditions, were actively seeking a new kind of 'perfection' in the handcrafted. This 'authenticity' was not just about aesthetics; it was a deeper yearning for a connection to fundamental modes of creation, to a pre-industrial honesty in artistic expression, a connection that African textiles embodied so powerfully. What hidden narratives, then, might these silent masterpieces have whispered across continents, offering an entirely new lens through which to perceive reality?

The Grand Tour (Without Leaving the Studio): Modernists and Their African Muses

Having understood the profound visual and philosophical language embedded within these textiles, the question then becomes: how did this rich tapestry of meaning actually reach the studios of European modernists, leading to what I like to call 'The Grand Tour (Without Leaving the Studio)'? It’s not like European modernists were all trekking through the Sahara with sketchbooks in hand, though I'm sure some adventurous souls might have! Their encounter with African art, including textiles, largely happened through ethnographic museums, colonial exhibitions, and the burgeoning art markets of major European cities.

Often, their initial encounter was within the stark, decontextualized halls of ethnographic museums or at grand colonial exhibitions, where they were frequently displayed as 'curiosities' or 'artifacts' rather than fully fledged artworks. It’s a curious paradox, isn't it? To find such profound inspiration born from such problematic acquisitions. Almost like finding a gem in the mud – the beauty undeniable, but the circumstances of its discovery certainly worth reflecting on, perhaps even with a wry, melancholic chuckle. This historical context of acquisition and display is, of course, a critical part of the dialogue around cultural influence today, prompting vital conversations about decolonization, restitution, and equitable artistic exchange. The act of decontextualizing these pieces in museum settings, stripping them of their original communal and spiritual significance, inadvertently forced European viewers to confront them purely as abstract forms, paving the way for a radical reinterpretation of art itself, challenging long-held Western notions of perspective and representation.

Yet, even through this imperfect, often Eurocentric gaze that romanticized the 'primitive' or 'authentic,' the impact was undeniable. While artists like Henri Matisse and Paul Klee were directly captivated by textiles, others, like Pablo Picasso in his Cubist period, were profoundly influenced by the broader forms and philosophies of African sculpture and masks, which shared many underlying principles of abstraction, challenging Western conventions of representation and perspective. These modernists weren't necessarily trying to copy these textile designs. No, no, that would be missing the point entirely, and, frankly, a bit lazy!

Instead, they were deeply affected by the principles at play: the flattened perspectives (where depth is minimized, and emphasis is on surface design, directly challenging Western art's long-held emphasis on illusionistic space and naturalism), the rhythmic repetition of motifs, the bold, non-naturalistic use of color, and the underlying spiritual or communal significance of the patterns. This was a direct challenge to Western art's long-held emphasis on perspective, naturalism, and individual genius. It offered a refreshing alternative, an artistic language that felt raw and vital, echoing a deeper truth. It really makes you think about how our own biases can shape what we choose to see, doesn't it?

If you're interested in the broader context, I highly recommend diving into understanding the influence of African art on modernism and exploring the enduring influence of indigenous art on modern abstract movements. It really helps put things into perspective, showing just how interconnected our global artistic heritage truly is. So, when these European minds encountered such profound visual languages, what internal shifts must have truly begun, slowly unpicking the threads of centuries of tradition?

Echoes on the Canvas: Specific Threads of Influence

When I look at a Fauvist painting by Henri Matisse, like his iconic 'The Red Room' (Harmony in Red), I don't just see vibrant color; I sense the rhythmic pulse of a drum, the bold, almost confrontational color blocks of a perfectly woven Kente cloth. His shift towards flattened planes, graphic shapes, and a rejection of traditional perspective, especially evident in his paper cut-outs (think 'La Gerbe' or 'The Snail'), directly echoes the visual strategies perfected in textile design. It's not imitation, mind you, but a deep absorption of aesthetic principles – a masterful re-weaving of visual ideas onto canvas or paper. As an artist, I often find myself drawn to this very idea: how a flat surface can hold infinite depth and narrative through color and form alone.

And then there’s Paul Klee, whose works often feel like ancient scripts, intricate and full of hidden meaning. He was deeply drawn to the linear quality and symbolic power inherent in textiles. His 'hieroglyphic' patterns, which seem to communicate abstract narratives, find striking parallels in things like Adinkra symbols from Ghana – visual proverbs, condensed wisdom woven into fabric. Each Adinkra symbol, such as Sankofa (return and get it) or Gye Nyame (except for God), carries a profound philosophical message. Klee understood that abstraction wasn't just about escaping reality, but about articulating a deeper one, much like these ancient symbols. You can find more about how these shifts occurred in the definitive guide to abstract art movements from Cubism to contemporary abstraction.

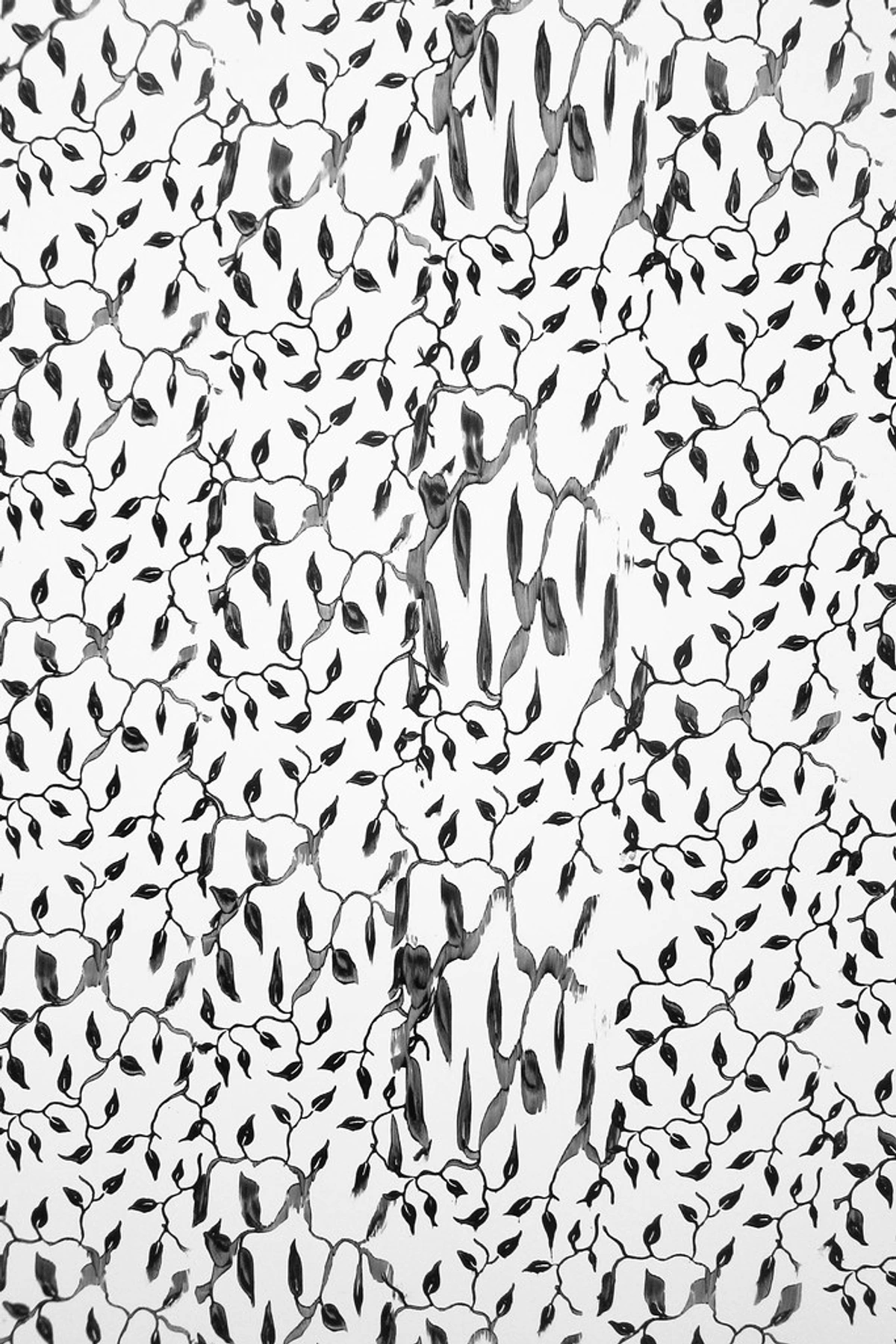

And the threads don't end there; they simply evolve. While artists like Christopher Wool, whose raw, often repetitive and graphic works I deeply appreciate, might not have directly referenced African textiles, there’s an undeniable resonance, a 'shared spirit' that whispers across generations. His bold, almost stencil-like patterns, his raw, textural approach to paint, and the rhythmic repetition in many of his pieces evoke the handmade, almost imperfect perfections of woven forms, or the graphic starkness of mud cloth, where patterns emerge from a deliberate, yet organic, process. Wool’s art often feels like a visual echo of urban decay and industrial grit, yet in its rhythmic, almost mechanical repetition and directness, it touches on a primal, intuitive mark-making. This echoes the raw authenticity and process-driven beauty of traditional African textiles, where the human hand, even with its subtle imperfections, creates profound, impactful visual statements. It’s not about direct imitation, but a continuation of a dialogue about the power of stark graphic forms, repetitive rhythms, and the raw authenticity of mark-making – a kind of artistic genetic memory, perhaps, guiding the hand even when the mind isn't consciously aware? It's like finding a familiar melody in a completely new song.

My Own Artistic Dialogue with Pattern and Meaning: An Introspective Approach

As an artist creating abstract art prints and paintings, I'm constantly aware of the layers of history and influence that precede my own brushstrokes. While I don't consciously set out to replicate African textile motifs, the principles I discussed — the power of pattern, the emotional language of color, the narrative potential of geometric forms, and the importance of texture in abstract art — are deeply embedded in my artistic DNA. I often find myself building up surfaces, creating rhythmic compositions that feel like a visual pulse, and letting my colors tell their own story, much like a master weaver. When I'm building up surfaces, creating rhythmic compositions, I often think about the repetition and slight, organic variations you find in a Bogolanfini pattern, or the deliberate, yet almost spontaneous, layering of a Kuba cloth. It’s that balance between intentional design and the spontaneous, almost tactile imperfections of the handmade that truly resonates with me. Each layer of paint, each nuanced brushstroke, feels like a thread in a larger, evolving narrative, a visual pulse that seeks to feel both ancient and utterly new, much like those timeless textiles. It makes me think about my own artistic journey and how every piece of art I've ever seen, every pattern, every color combination, subtly informs what I create today. It's like having a vast, invisible library in your mind, and you're always pulling references without even realizing it. Perhaps that's why visiting a place like my museum in Den Bosch can be so inspiring – you see these connections jump out at you, challenging you to see the world, and art, in a new light. It's in those quiet moments of connection that I often find my next inspiration, feeling the echoes of ancestral patterns guide my hand, urging me to weave my own contemporary stories.

The Unfolding Tapestry: Contemporary Echoes and Decolonizing the Gaze

The narrative of African textile influence doesn't merely reside in the annals of early modernism; it continues to unfold, creating a richer, more nuanced tapestry in contemporary art. Today, we witness a powerful shift where contemporary African artists are not just acknowledging but actively reclaiming and reinterpreting their own textile heritage. Artists across the continent are using traditional techniques – from weaving and dyeing to appliqué and beadwork – in innovative ways, creating contemporary art that speaks to modern identities while deeply rooted in ancestral wisdom. This isn't about looking to the West for validation; it's about a vibrant, self-aware dialogue with their own cultural legacy.

Furthermore, the discourse around cultural influence has evolved significantly. The crucial conversations around decolonization, restitution, and equitable artistic exchange mean that the often-problematic initial encounters between European modernists and African art are being critically re-examined. What was once seen as 'discovery' or 'inspiration' is now understood within a framework that emphasizes cultural appreciation and dialogue over appropriation. Many contemporary artists from around the world engage directly with African artists and traditions, fostering collaborative works that honor source cultures and create new, hybrid expressions that enrich rather than exploit. The influence is no longer a one-way street, but a complex, multi-directional flow of ideas, techniques, and philosophies, constantly weaving new patterns into the global fabric of art.

FAQ: Unraveling the Threads of Influence

Here are some common questions I hear about this fascinating topic:

Question | Answer |

|---|---|

| What are African textiles? | These are diverse woven, printed, or dyed fabrics created across various African cultures, often characterized by intricate patterns, vibrant colors, and deep symbolic meaning. Examples include Kente, Adinkra, Bogolanfini (mud cloth), Kuba cloth, Adire, and Ndebele beadwork. |

| Which modern artists were influenced? | Key figures include Henri Matisse, Paul Klee, Pablo Picasso (especially his Cubist period with general African art influence), and later, many artists exploring abstraction and pattern, whose work shows a 'shared spirit' with these foundational principles, like Christopher Wool. |

| How did artists encounter these textiles? | Primarily through ethnographic museums, colonial exhibitions, and burgeoning art markets in European cities, where African artifacts were displayed and collected, often under questionable circumstances due to colonial expansion and viewed through a Eurocentric lens. |

| Is this considered cultural appropriation? | This is a complex but crucial question, one that every artist grappling with influence must consider. While early modernists often viewed these influences through a Eurocentric lens that sometimes lacked full cultural understanding or proper attribution, contemporary discourse rightly emphasizes the importance of moving beyond mere aesthetic borrowing. It's about fostering respectful engagement, thorough research, proper attribution, and a deep understanding of the cultural context. The conversation has shifted towards cultural appreciation and dialogue, recognizing these influences as part of a shared, global artistic heritage rather than isolated 'discoveries.' Today, many contemporary artists from around the world engage directly with African artists and traditions, leading to collaborative works that honor source cultures and create new, hybrid expressions that enrich rather than exploit, ensuring the legacy is a two-way conversation. |

| What characteristics were most influential? | Artists were drawn to the abstract, geometric patterns, bold non-naturalistic color palettes, rhythmic repetition, flattened perspectives, and the symbolic/narrative qualities inherent in many African textile designs, alongside the philosophical idea of communal creation and the raw authenticity of the handmade. |

Weaving a Richer Tapestry of Art History: Legacy and Dialogue

The influence of African textiles on modern and contemporary abstract art is a beautiful testament to the interconnectedness of human creativity. It reminds us that art doesn't exist in a vacuum; it's a dynamic conversation, a constant flow of ideas and aesthetics across cultures and generations. This ongoing dialogue continues to inspire contemporary abstract artists globally, moving beyond direct imitation to a deeper engagement with the principles of pattern, symbolism, and the spiritual power of art. It prompts us to reflect not just on what art is, but how it connects us, across time and space. When we look closely, we can see the echoes of ancient patterns in seemingly contemporary forms, enriching our understanding and appreciation of both. So, the next time you encounter an abstract painting, take a moment. You might just spot a hidden thread, a whisper from a distant loom, adding another layer of meaning to the canvas – a layer woven from millennia of human creativity, crossing oceans and centuries, and continuing to shape our visual world. And honestly, isn't that just the most wonderfully complex and utterly human thing to consider? A silent, vibrant dialogue that continues to unfold, revealing more with every glance.