Ancient Egypt's Enduring Echo: Shaping Modern Art's Soul – An Artist's Journey

Uncover the profound connections between ancient Egypt's timeless aesthetic and modern art. Join an artist's personal journey, exploring its unexpected influence on Cubism, Fauvism, De Stijl, and Neo-Expressionism, and how these ancient whispers still inspire today.

What if the soul of modern art whispers secrets from the sands of ancient Egypt?

The Timeless Echo: How Ancient Egypt Shaped Modern Art's Soul – An Artist's Perspective

Sometimes, when I'm absorbed in a piece of modern art—all its sharp angles, vibrant colors, and simplified forms—a peculiar, almost insistent whisper washes over me: "This visual language… this feeling… I've encountered it before." It's a curious sensation, one that always makes me wonder about our celebrated 'originality.' Is it, in fact, a deeply thoughtful, perhaps even unconscious, reinterpretation of universal artistic principles like order, permanence, and symbolic representation? For me, that recurring echo invariably leads back to the sun-drenched sands and enigmatic tombs of ancient Egypt. And honestly, it still surprises me every time, like finding a secret passage in a familiar museum. At first glance, it might seem a stretch, perhaps even a bit cheeky (I admit, I sometimes chuckle at the idea myself), to suggest a connection between modern art—often heralded for its revolutionary break from tradition—and the millennia-old conventions of a civilization built on permanence. But I promise you, the connection isn't just there; it's profound and deeply ingrained, a secret handshake between distant epochs.

Ancient Egypt, with its remarkably sophisticated visual language, wasn't just creating beautiful objects; it was articulating foundational aesthetic principles that would, centuries later, provide an unexpected blueprint for many modern art movements like Cubism, Fauvism, De Stijl, and Neo-Expressionism. In this article, we'll peel back the layers to uncover how the distinct aesthetic of ancient Egypt profoundly influenced the bold strokes of these movements. Come along, let's listen for those ancient whispers, and maybe even find a few unexpected chuckles along the way, as we journey from pharaohs to Picassos.

My Personal Fascination: The Enduring Allure of Egypt and the Roots of Modernism

I can still feel the chill of the museum hall, the faint scent of old stone, and the sudden, overwhelming presence of a colossal granite statue. I was probably no older than ten, all wide-eyed wonder and a vague hope of finding a hidden treasure map (and yes, sometimes I still wish for that map!). Back then, my fascination with Egyptian art was, predictably, all about the shiny gold and the spooky mummies. But standing there, as an adult, before the simplified, monumental forms of an Egyptian deity or pharaoh, the undeniable gravitas of ancient Egypt simply demanded a deeper kind of attention. It wasn't merely the scale or the vibrant, perfectly preserved colors; it was the palpable sense of an entire civilization meticulously dedicated to eternity. Art, from its vibrant tomb paintings and intricate relief sculptures to its imposing statuary, served as its primary, eloquent language—profound communications with the gods, with the afterlife, with the very concept of forever. This personal encounter with the enduring power of Egyptian art was the catalyst, sparking my journey into understanding Egypt's deeper artistic influence, and how its visual language might have resonated with later artistic revolutions, even into the revolutionary movements of modern art. This awe led me to explore the broader artistic climate that made such ancient influences so potent.

For centuries, Western art was fixated on strict realism, linear perspective, and the celebration of the individual. But by the late 19th and early 20th centuries, artists were starting to feel like they were repeating themselves, that the traditional artistic vocabulary had become exhausted. The advent of photography, for instance, freed painting from its mimetic obligations, prompting artists to ask: "If a camera can capture reality, what is painting's true purpose?" This period of intense societal change, marked by industrialization, rapid urbanization, the rise of cinema, shifting philosophical outlooks (think Nietzsche's critique of traditional values or Freud's exploration of the subconscious), increased global travel, burgeoning archaeological discoveries, and new scientific theories (like Einstein's relativity challenging fixed perspectives), spurred a desire for something raw, elemental, something that spoke to deeper universal truths beyond a mere photographic likeness. For me, it felt like the world was fragmenting into a beautiful, terrifying mosaic, and artists, perhaps unconsciously, were seeking new ways to make sense of it, or simply to express the profound chaos and wonder.

It was during this era that the doors swung open to what was then termed "primitivism"—art from non-Western cultures, often viewed, let's admit, through a rather problematic colonial lens. But despite this, it sparked an aesthetic revolution. Archaeological discoveries (like the tomb of Tutankhamun in 1922, which caused a global sensation), world's fairs, newly published studies, and particularly the extensive collections in ethnographic museums brought these ancient aesthetics—including not just Egyptian artifacts but also African masks and Oceanic art—into contemporary European consciousness. Suddenly, ancient Egypt, with its potent symbolism and distinct aesthetic, was remarkably in vogue. For artists seeking authenticity and a rejection of Renaissance conventions, it felt like a profound stripping away of superficial layers, a rediscovery of universal forms and essential truths, an an attempt to reconnect with a perceived spiritual depth that many felt was lost in Western traditions. The allure wasn't just in the exoticism; it was in the perceived 'rawness,' 'directness,' and 'spiritual power' that contrasted sharply with the academic strictures of European art, offering a fresh visual vocabulary and a path to deeper meaning. Influential figures like Pablo Picasso and Fernand Léger, for example, were known to frequent these museums, studying these forms with an intense curiosity that would later manifest in their revolutionary work.

Deconstructing Form: Cubism's Geometric Echoes and Egyptian Conceptualism

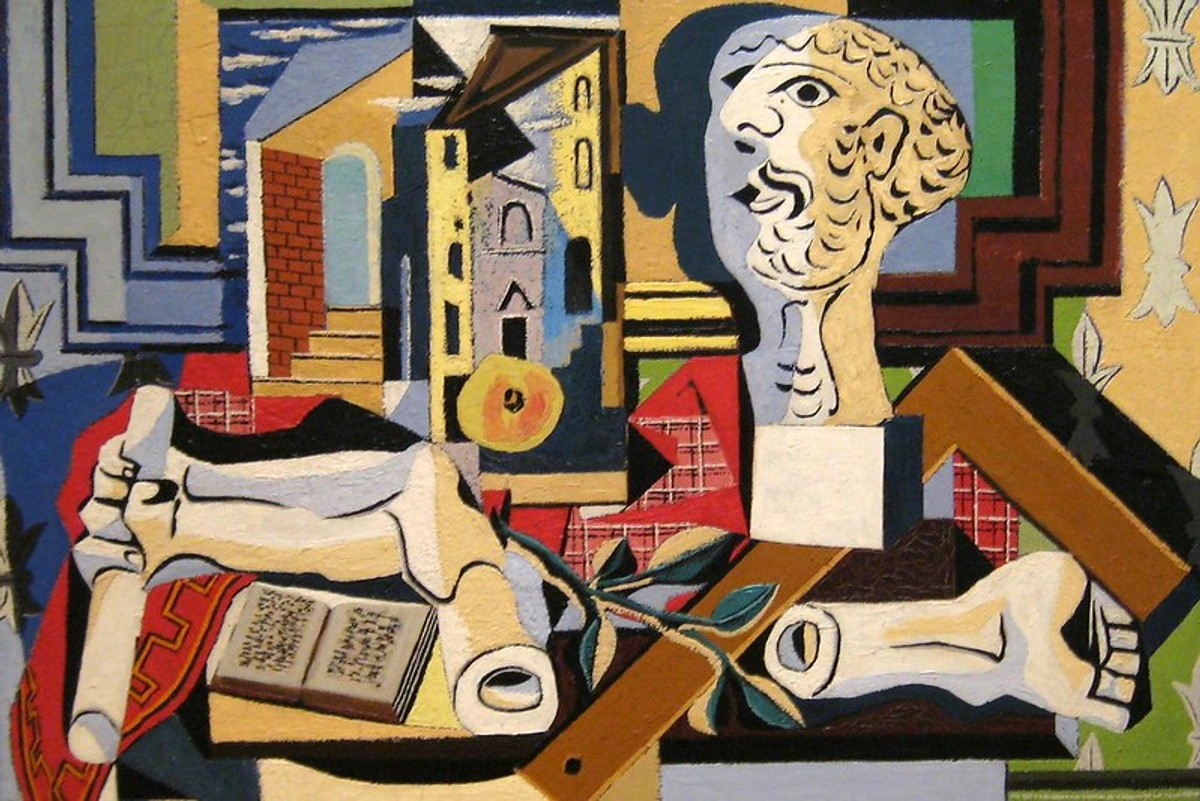

When I first delved into Cubism, I confess, my brain performed a mild intellectual gymnastics routine, leaving me feeling like a bewildered tourist trying to read a map written in a foreign language. All those fragmented planes and multiple viewpoints! Yet, a striking thought then occurred to me: wasn't this, in a profound conceptual sense, something that ancient Egyptian art had been exploring for millennia? Not a literal mirror, of course, but a shared philosophy of representation. What I found fascinating was the iconic depiction of an Egyptian pharaoh: a frontal torso, a profile head, and an eye seen from the front. This wasn't about capturing how the body looked from a single, fleeting angle, but about conveying what the body was—a composite assembly of its most characteristic and identifiable parts, like a blueprint showing all essential components at once, rather than a single photograph. This deliberate approach, coupled with hieratic scale (a system where the size of figures indicates their importance, not their distance), ensured clarity, narrative, and, crucially, permanence for the spirit, or Ka, in the afterlife.

This pursuit of fundamental truths and cosmic balance, often referred to as Ma'at, resonated with Cubism's search for underlying structure. Ma'at, representing universal order, truth, and justice, was visually expressed in Egyptian art through balanced compositions, symmetrical arrangements, and symbolic motifs, all striving for eternal harmony. For example, think of the reliefs and paintings found in the Tomb of Ramose in Thebes, where figures are consistently presented in this composite view, emphasizing their essential form rather than a naturalistic snapshot. Crucially, these figures were often rendered with meticulously strong outlines and deliberate flatness to their planes. This emphasis on distinct, almost segmented planes, coupled with the composite view, provided a powerful visual precedent for the Cubist fragmentation of forms, where objects are broken down into geometric facets and reassembled. The stark, clear contours and the reduction of three-dimensional reality to a flat surface in Egyptian art offered a blueprint for Cubism's revolutionary approach to form.

Artists like Pablo Picasso and Fernand Léger, in their radical quest to break down and reassemble reality, found an unexpected kinship with these ancient principles. They weren't merely copying; rather, they found a powerful validation for their own revolutionary ideas about representation. The deliberate flatness, the bold emphasis on basic geometric forms, and the profound idea that a figure could be understood not solely by its superficial appearance but by its underlying essence—these were conceptual pillars that ancient Egypt had championed thousands of years prior. It was like an artistic 'aha!' moment when I realized that the Egyptians, in their pursuit of eternal truth, had already laid a conceptual groundwork for depicting the multifaceted nature of reality. For more insights into this groundbreaking movement, explore our Ultimate Guide to Cubism.

Léger, deeply fascinated by the machine age and the industrial landscape, found particular resonance in Egyptian art's strong contours and monumental, almost impersonal, figures. He admired the impersonal, universal quality he saw in Egyptian art, which perfectly suited his vision of a modern world built on order and efficiency. It's as if both the ancient Egyptians and the Cubists understood that sometimes, to truly capture the profound truth of something, one must simplify it, pare it down to its most fundamental shapes and essential components.

So, what truths are you trying to capture by simplifying the world around you?

Key Takeaway: Egyptian art offered Cubism a conceptual framework for representing multifaceted reality, prioritizing essence over fleeting appearance, and inspiring the use of strong outlines and geometric forms, particularly through its composite views of figures that combined profile and frontal perspectives.

Color and Emotion: Fauvism's Vibrant Connection and Egyptian Symbolism

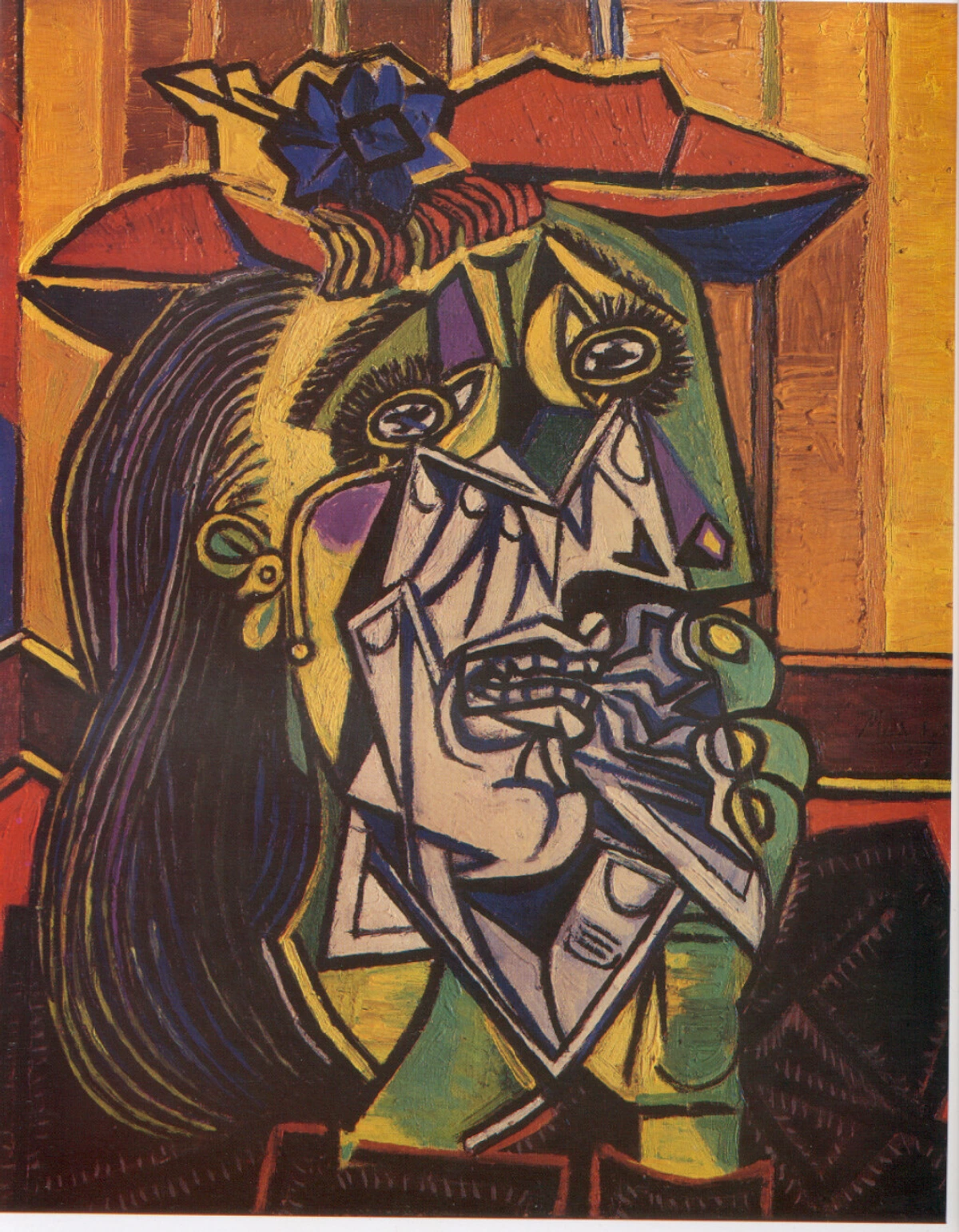

If Cubism meticulously deconstructed form, Fauvism erupted as an unbridled explosion of color. This movement, too, felt the subtle pull of ancient Egypt's visual language. Henri Matisse and his contemporaries gleefully cast off the shackles of realistic color, employing hues for pure, unadulterated emotional expression. You see a green face, a blazing red room, and the impact is immediate, visceral, and intense, isn't it? It's a declaration of feeling, raw and unfiltered. And again, my mind inevitably drifts back to the incredibly vibrant tomb paintings and papyri of ancient Egypt.

Ancient Egyptian artists, while working with a different intent, employed color not to perfectly mimic reality but to convey profound meaning, symbolism, status, and even emotional impact. Using natural mineral and plant pigments—like malachite for green (fertility, new life) and lapis lazuli or indigo for blue (divinity, heavens, cosmic power)—their colors were applied boldly, often flat and outlined, prioritizing symbolic meaning over the subtle shading of reality. The precision of their pigment preparation and application allowed these colors to retain their vibrancy for millennia, emphasizing the enduring message. Red, for life, power, and the fiery desert, was used with a directness and boldness that, while rooted in symbolism, shares a kindred spirit with the Fauvist liberation of color and its emotional punch. The Egyptians understood that color was more than just descriptive; it could evoke a spiritual state, signify divine power, or impart a sense of awe, making it a powerful tool for emotional and spiritual impact. For instance, the vivid, flat colors depicting scenes from the afterlife in the Tomb of Nefertari showcase this powerful, symbolic use of color, where each hue communicates a specific aspect of the cosmic order, status, or even a particular emotional state intended for the viewer (divine awe, protection, hope). This deliberate flatness and the use of expansive, unmodulated color fields in Egyptian tomb paintings, designed for immediate symbolic and spiritual impact, also offered a visual precedent for Fauvism's bold, unmixed areas of color. There’s a certain uninhibited joy in both approaches, a profound recognition that color itself holds immense power far beyond mere description, capable of evoking deep emotional and spiritual responses. For more about this, see our guides on How Artists Use Color and The Psychology of Color in Abstract Art: Beyond Basic Hues.

Look at Matisse's iconic "La Danse"—those bold, flat figures, the pure, unmixed colors of the sky and grass. It's not about intricate detail but about the sheer, exhilarating emotional impact of form and color combined. It pulsates with a primal energy, much like the rhythmic, stylized figures you'd find dancing across ancient temple walls or adorning sarcophagi, designed to convey a sense of eternal movement and vitality. Perhaps it’s a shared, intuitive understanding that certain visual keys unlock universal feelings and spiritual connections, regardless of the millennia separating them. Dive deeper into the Fauvist movement with our Ultimate Guide to Fauvism.

When you look at a burst of color, what uninhibited joy or raw emotion does it spark in you?

Key Takeaway: Fauvism's liberation of color for emotional impact echoes ancient Egypt's symbolic, bold, and flat application of color to convey profound meaning, status, and emotional/spiritual resonance, creating striking visual compositions and a sense of divine power.

Geometric Abstraction: The Spiritual Order of Lines and Egyptian Precision

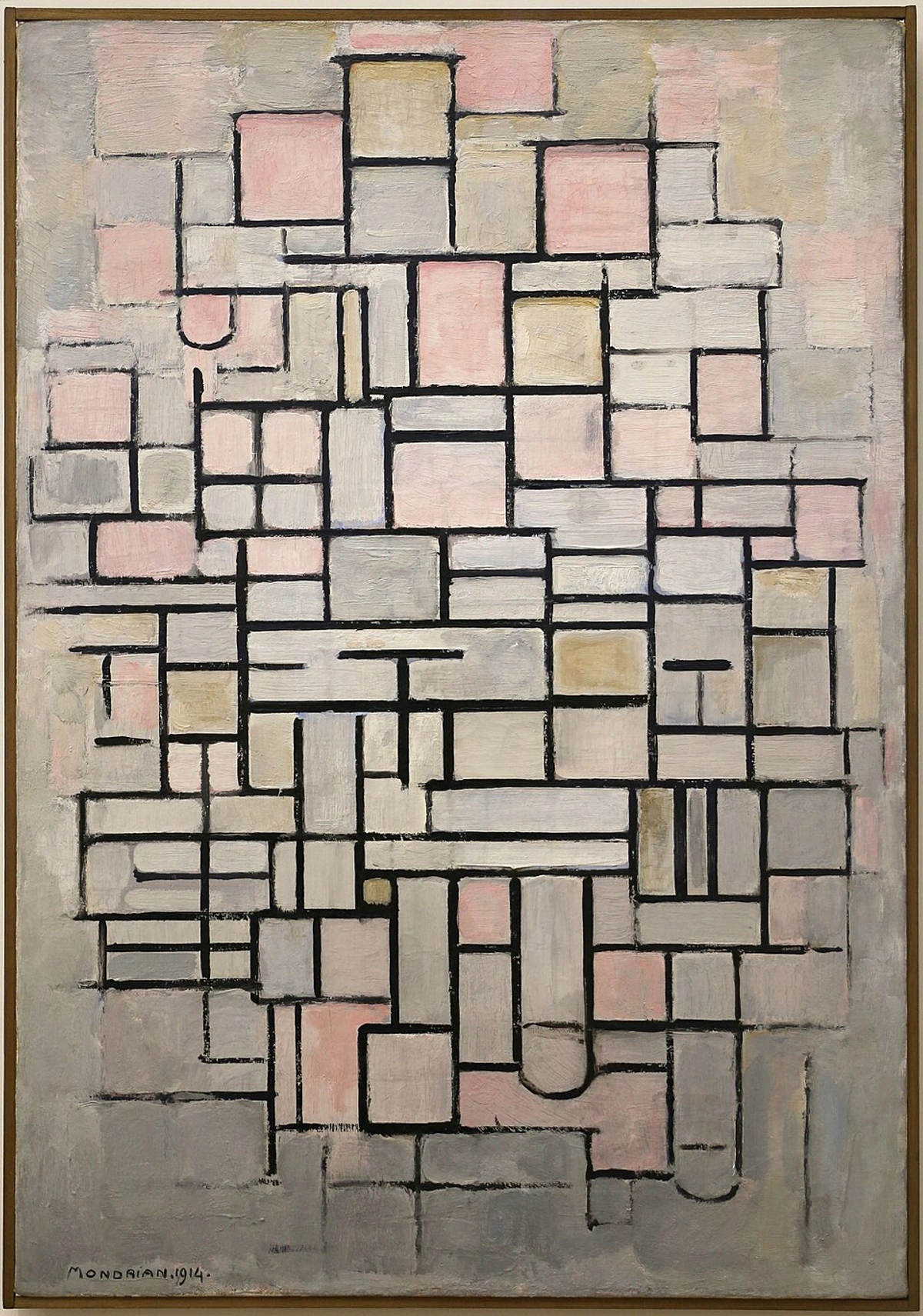

And then we encounter artists like Piet Mondrian, a pioneer of De Stijl, whose work also subtly channels ancient echoes. Oh, Mondrian! Those crisp black lines, primary colors, and stark, meticulously balanced compositions. You might initially think, "What on earth does this have to do with ancient Egypt?" But if you examine ancient Egyptian design closely—the precise geometry of their hieroglyphs, the meticulously calculated grid systems used to proportion figures and architectural elements, the sheer architectural solidity of their temples, and monumental structures like the pyramids, often built using principles like the Golden Ratio—there's an undeniable, deep-seated appreciation for order, balance, and an underlying structural harmony. These architectural marvels, with their imposing geometric forms and precise construction, are testaments to a belief in cosmic order. They embody a deep reverence for Ma'at, often using mathematical precision to reflect universal principles in art and design. Consider the perfect alignment of the Great Pyramids of Giza with astronomical points, or the rigorous planning evident in temple complexes like the Great Temple of Amun at Karnak, all rooted in an abstract sense of structural clarity. The grid lines visible on unfinished tomb paintings in the Valley of the Kings further demonstrate an unwavering commitment to proportional accuracy and abstract order. My brain, when faced with such precision across millennia, sometimes just throws its hands up and declares, "Okay, humanity really does love straight lines and perfect angles!" Mondrian, in his profound quest for universal spiritual harmony through pure abstraction, wasn't seeking to mimic Egypt directly. But he, much like the ancient Egyptians, found immense meaning in simple, geometric elements. Both sought to transcend the chaotic surface of everyday reality and tap into a deeper, more fundamental, universal order.

What I find fascinating is this shared, almost spiritual belief: that immense power and profound truth can exist in the most simplified forms—a clean line, a block of pure color. These elements reflect a cosmic balance. When I look at a Mondrian, I sometimes wonder if, somewhere deep in our collective artistic DNA, there’s a blueprint for order that Egypt helped define, a kind of primal yearning for structural clarity. Discover more about how geometry conveys meaning in The Symbolism of Geometric Shapes in Abstract Art.

Do you ever feel a craving for pure, unadulterated order amidst life's beautiful mess? Perhaps a simple line or block of color can satisfy that primal artistic hunger, echoing ancient wisdom.

Key Takeaway: Mondrian's quest for universal harmony through geometric abstraction finds a profound conceptual ancestor in ancient Egypt's meticulous grid systems, architectural precision, and deep reverence for cosmic order and mathematical proportioning, evident in its monumental constructions.

Foundational Principles: Beyond Form, Color, and Into Eternity

Beyond specific art movements, ancient Egyptian art offered a broader toolkit of universal principles that deeply resonated with modern artists seeking enduring meaning and innovative forms. These principles, rooted in a culture dedicated to permanence and divine communication, transcend mere stylistic imitation to offer a profound conceptual blueprint.

Stylization and Iconography: The Power of Essence and Narrative

Egyptian artists weren't aiming for naturalism; instead, they developed a highly stylized visual language that prioritized clarity, permanence, and the communication of an object's essential nature over its fleeting appearance. This focus on abstracting reality to its core elements was a powerful precursor to the widespread adoption of abstraction in modern art. Crucially, they employed a strict canon of proportions, a set of rules governing the size and relationship of body parts, ensuring consistency and an idealized, eternal representation, a concept that appealed to modern artists seeking underlying structural principles. Furthermore, ancient Egyptian iconography, where specific symbols, figures, and colors carried pre-determined meanings, offered a blueprint for conveying complex narratives and abstract ideas through visual shorthand. Think of the Ankh, representing 'life,' or the Eye of Horus, a powerful symbol of protection and royal power. Beyond these, the depiction of the scarab beetle symbolized rebirth and the sun, resonating with themes of transformation and renewal often explored in modern art. Specific crowns and regalia clearly denoted the wearer's divine authority or the Ma'at, representing cosmic order and justice. Even iconic depictions of deities, such as Horus (often a falcon or falcon-headed man), Anubis (a jackal or jackal-headed man), or Thoth (an ibis or ibis-headed man), were powerful narrative devices, using stylized animal forms to represent divine attributes and roles. The intricate hieroglyphic writing system itself, combining pictorial and phonetic elements, offered a powerful example of how stylized images could communicate complex narratives and abstract ideas with profound efficiency and symbolic weight, influencing modern artists' interest in visual language and signs. The Book of the Dead, with its extensive use of images and text, was designed to act as a map and guide for the deceased through the perils of the afterlife, illustrating how deeply art served as a clear narrative tool to convey existential stories. This narrative clarity, where art was meant to convey a story or message explicitly, also found echoes in modern conceptual art where the idea itself is paramount. For a deeper dive into how art conveys meaning, explore The Definitive Guide to Understanding Symbolism in Art.

Materiality, Monumental Scale, and the Enduring Spirit

The very materiality and monumental scale of much Egyptian art—from colossal statues carved from enduring granite and basalt to meticulously painted tomb chambers using techniques like fresco and relief carving—also conveyed a sense of timelessness and impact. These durable materials and large-scale creations were not just aesthetic choices but served to project power and ensure permanence, crucial for a culture deeply focused on the afterlife and maintaining cosmic order. This deep-seated 'why' behind Egyptian permanence, their belief that the spirit (like the Ka, representing life force and the essence of an individual that needed an earthly vessel to return to, and Ba, the personality or soul, capable of travel between worlds) needed an earthly representation to return to, found an unexpected echo in modern artists striving to create works of enduring significance, exploring themes of mortality, transcendence, and the human condition. Consider the iconic frontal presentation and simplified, block-like forms of Egyptian sculpture, designed to be viewed head-on and embody an eternal, unchanging presence. This approach to monumental sculpture, prioritizing essential form over fleeting detail, offered a powerful precedent for modern sculptors interested in conveying universal human experience through simplified, powerful forms that demand a timeless contemplation.

The Role of Religion and the Afterlife

A fundamental driver behind the unique characteristics of ancient Egyptian art was its profound connection to religion and the afterlife. The Egyptians believed in an eternal existence, where the earthly body was merely a temporary vessel for the soul. Art, therefore, was not merely decorative; it was functional, serving as a conduit between the living and the dead, ensuring the continued existence and well-being of the deceased in the spirit world. This deeply spiritual imperative led to the emphasis on permanence (durable materials, monumental scale), clarity (stylization, composite views for unambiguous identification), and symbolism (colors and motifs with specific meanings). For modern artists, even those operating in a secular context, this underlying intent—to create art that transcends the temporal and speaks to universal human conditions or spiritual aspirations—resonate deeply, providing a conceptual framework for their own quests for enduring meaning and impact.

Echoes Across Eras: A Quick Look

Ancient Egyptian Principle | Modern Art Movement Example | How It Manifests |

|---|---|---|

| Composite View | Cubism | Breaking down figures/objects into geometric facets, multiple viewpoints simultaneously. |

| Symbolic, Flat Color | Fauvism | Using color for emotional impact and meaning, not strict realism; bold, unmodulated hues. |

| Geometric Order & Grids | De Stijl | Quest for universal harmony through simplified lines and primary colors, structural clarity. |

| Stylization & Iconography | Neo-Expressionism | Use of potent symbols, simplified figures, and visual shorthand to convey narrative/identity. |

| Monumental Scale & Materiality | Modern Sculpture | Creating works of enduring significance, using simplified, powerful forms for timeless contemplation. |

| Canon of Proportions | Abstraction | Interest in underlying structures and idealized forms, moving beyond surface appearance. |

| Hieroglyphic Writing | Conceptual Art/Visual Language | Combining pictorial and textual elements to convey complex ideas and narratives efficiently. |

How do you find order and eternal meaning in the seemingly chaotic world around you? Perhaps through the spiritual harmony of geometric forms, or the enduring power of a simple, potent symbol...

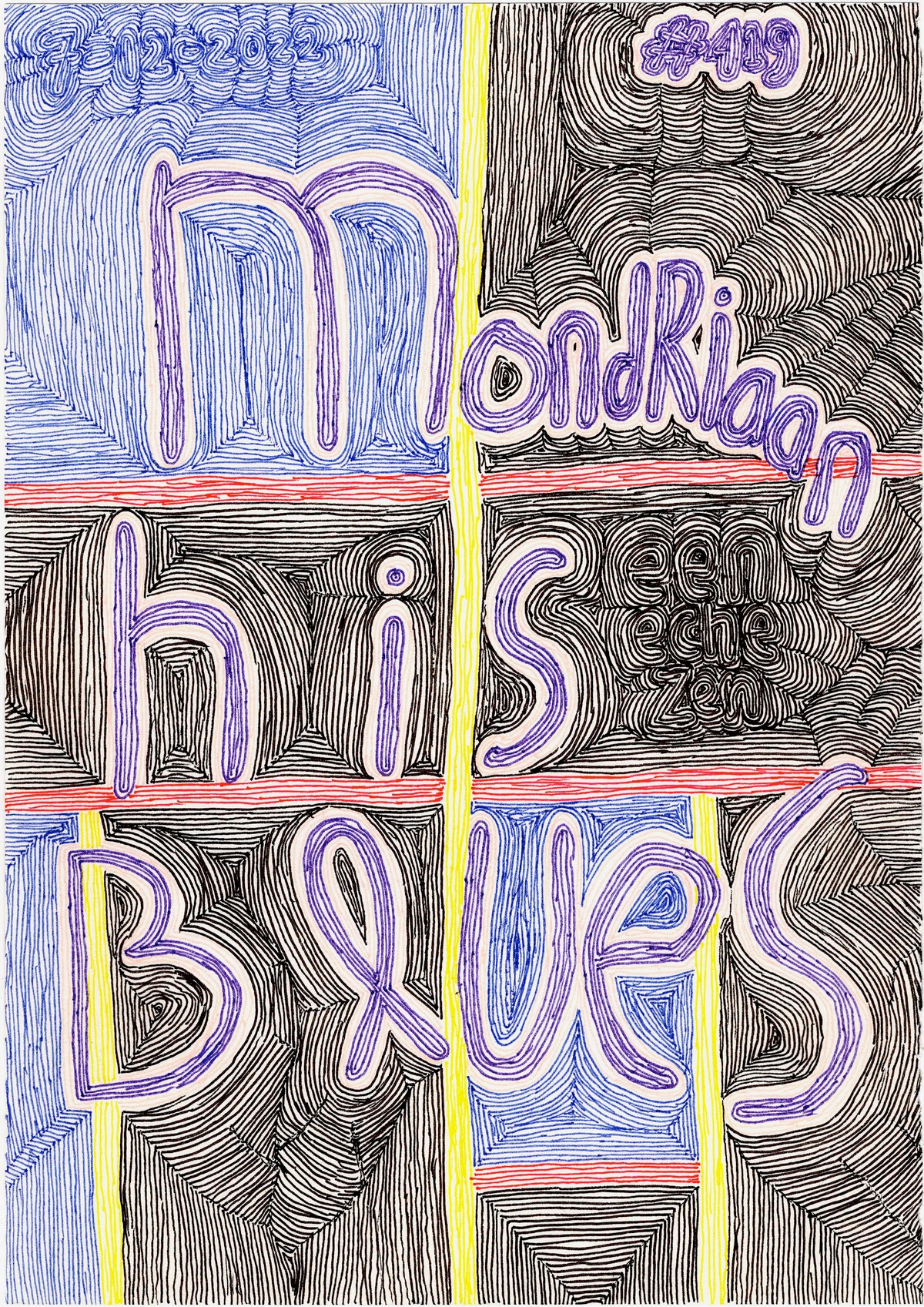

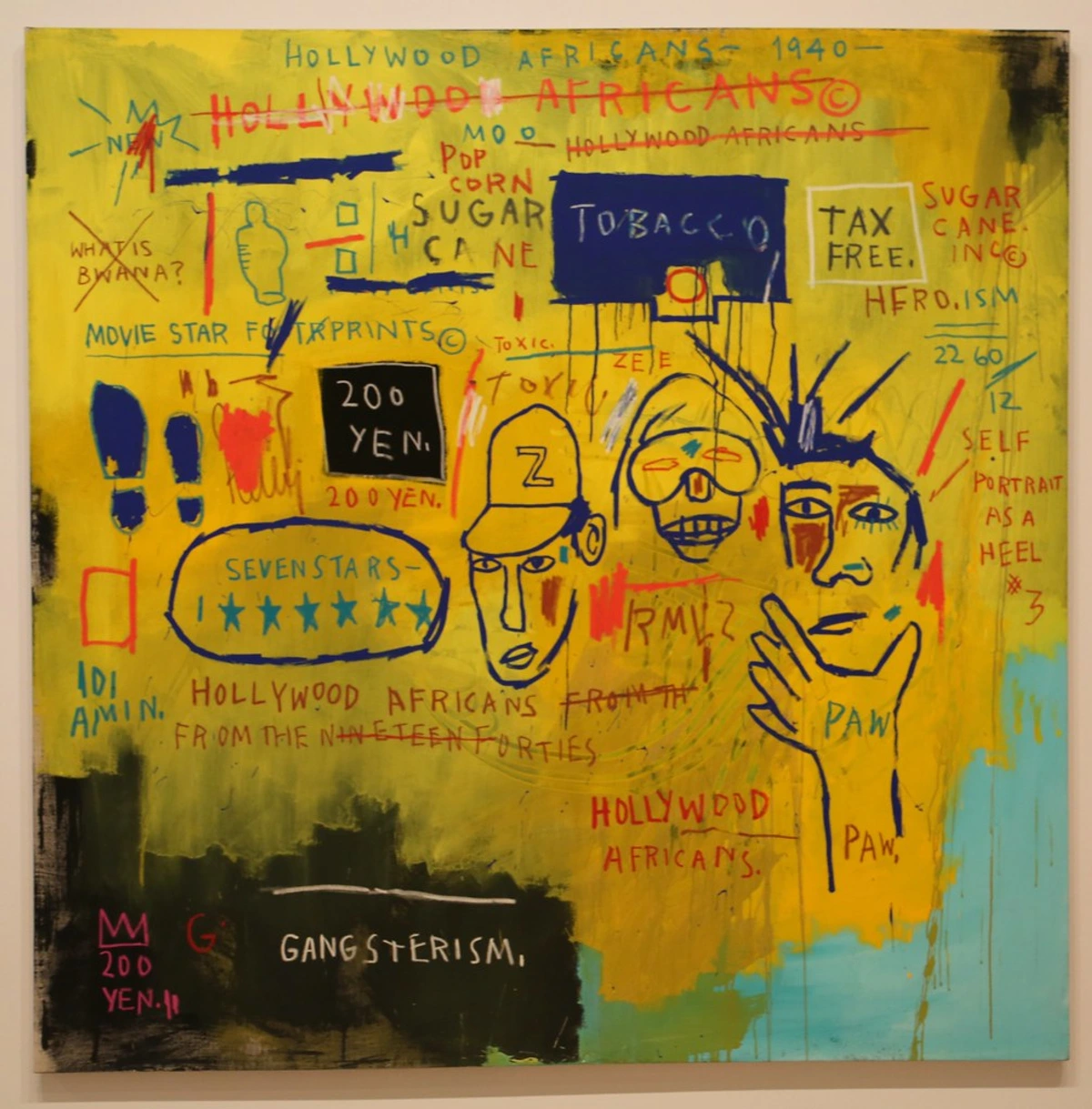

Beyond the Canvas: Basquiat and the Living Legacy of Neo-Expressionism

The echoes don't cease with early Modernism; they reverberate into later periods and different styles. Fast forward to the late 20th century, and you find powerful figures like Jean-Michel Basquiat, a pivotal artist of Neo-Expressionism. His raw, almost childlike drawings, layered with text and symbols, strike me as a direct descendant of ancient pictorial narratives. The flattened figures, the powerful symbolic nature of isolated elements, and the way he masterfully told complex stories through a highly simplified, yet impactful, visual language—it’s all undeniably present. His frequent use of crowns, for instance, evokes the enduring power and status conveyed by ancient Egyptian pharaonic regalia, reflecting a similar intent to communicate authority, divine connection, and historical legacy within a contemporary context. Beyond crowns, Basquiat often incorporated skull motifs, evocative of mummification masks or the cult of the dead, or repeated glyph-like symbols that mirrored the symbolic shorthand of hieroglyphs. He also shared with ancient Egyptian art a penchant for stylized animal forms, using them as powerful totems or narrative devices, much like the sphinx or jackals symbolized deities or royal power. All these elements contributed to his potent visual language. For a comprehensive look at his impact, see our Ultimate Guide to Jean-Michel Basquiat. You can also dive into the movement itself with our Ultimate Guide to Neo-Expressionism.

Basquiat was profoundly fascinated by history, by roots, and by the visceral expression of identity through powerful, almost glyph-like imagery. His painting "Hollywood Africans," for instance, exemplifies his use of flattened, stylized figures combined with a rich tapestry of symbols and text, creating a powerful, multi-layered narrative that functions much like ancient hieroglyphic inscriptions on a tomb wall. This sense of urgency and direct communication of complex ideas through stylized forms is a clear, if perhaps unconscious, continuation of an ancient artistic impulse.

His work, while utterly contemporary in its urgency and street art influences, carries an ancestral weight, a primal energy that connects directly to the earliest forms of human expression, including, undoubtedly, the iconic visual language of ancient Egypt. It's a powerful testament to how these ancient motifs aren't inert; they're living ideas artists draw upon to articulate profound truths. For more on how symbols shape narratives, delve into The Definitive Guide to Understanding Symbolism in Art.

What narratives are you telling, or seeing told, through the contemporary symbols that surround us?

Key Takeaway: Basquiat's Neo-Expressionist fusion of stylized figures, text, and potent symbolism directly channels the narrative power, ancestral weight, and iconic status found in ancient Egyptian iconography and hieroglyphs, often incorporating motifs like crowns (linked to divine authority), skulls, and glyph-like characters.

My Own Canvas: Finding Ancient Echoes in Modern Hues

As an artist, I often find myself wrestling with the very same fundamental questions about form, color, and meaning that these masters, ancient and modern, grappled with. Sometimes, when I’m staring at a blank canvas, I just want to capture an ephemeral emotion, a rhythmic pulse, or a specific, potent idea, and realism simply feels... restrictive, like trying to shout through a keyhole. It's in those moments that I instinctively strip things down, simplify shapes, and let color do the heavy lifting—much like I imagine ancient Egyptian artisans did when meticulously telling their eternal stories. Learn more about embracing abstraction in How to Abstract Art.

For instance, when I was working on a piece I called "Crimson Cascade," I initially tried to render a complex emotional landscape realistically. It felt clunky, diluted, and frankly, a bit like trying to fit an elephant into a teacup. Then, I remembered the bold, unmixed reds and blues of Egyptian tomb paintings, how they communicated raw power and divinity without fuss. I thought of the striking simplicity of the Eye of Horus, a potent symbol rendered with minimal, powerful lines. I found myself stripping away the fussy details, reducing forms to their essential geometric bones—much like the Egyptians with their hieroglyphs—and using unblended, primary colors to convey uncontained energy and sorrow—sharp angles for energy, visceral reds for sorrow, perhaps a flicker of cool blue for quiet reflection. I even experimented with a direct, flat application of pigments, reminiscent of ancient Egyptian fresco secco techniques, to maximize the intensity of each hue. The directness, the emphasis on essence over detail, truly unlocked the piece. You can explore some of my current creations for sale on my art for sale page, or dive deeper into my personal artist's journey to see how my influences have evolved. There's a piece of me, I suppose, trying to find that timeless quality, that enduring, resonant power, in every abstract stroke, striving for that "secret handshake" between eras. If you're ever in the Netherlands, you could even visit my museum in 's-Hertogenbosch!

Frequently Asked Questions

To further clarify some of these fascinating connections, here are answers to common questions about ancient Egyptian art's influence on modern art:

Q: What is primitivism in modern art?

A: Primitivism was a Western art movement from the late 19th and early 20th centuries that borrowed visual forms, motifs, and stylistic elements from non-Western or prehistoric cultures. Artists often romanticized these cultures, believing them to offer a more authentic, instinctual, or raw form of expression than the sophisticated traditions of European art. It was a complex reaction against the perceived decadence and academic constraints of Western society and art, yet it undeniably broadened the artistic palette. For a deeper understanding, read Understanding the Influence of African Art on Modernism.

Q: What are the ethical considerations surrounding "primitivism" in modern art?

A: "Primitivism" is often viewed critically today due to its problematic origins in a colonial worldview. It frequently involved cultural appropriation, where elements from non-Western cultures were taken out of context, romanticized, and sometimes inaccurately portrayed, reinforcing stereotypes. While it undeniably sparked aesthetic innovation in Western art, it is crucial to acknowledge the power imbalances and reductive interpretations inherent in the movement's historical framework. When drawing inspiration from ancient or non-Western cultures, the contemporary discussion emphasizes the importance of respectful engagement, thorough understanding of context, and attributing cultural sources appropriately, moving beyond mere exoticism or appropriation.

Q: Was Egyptian art consciously copied or conceptually reinterpreted by modern artists?

A: Primarily, ancient Egyptian art was conceptually reinterpreted by modern artists rather than directly copied. While some motifs might have been superficially borrowed, the deeper influence lay in the inspiration derived from Egyptian art's underlying principles: its emphasis on essence over fleeting appearance, its symbolic use of color, its geometric order, and its composite views. Modern artists absorbed these ideas and translated them into new, revolutionary forms that suited their contemporary artistic goals, rather than merely replicating ancient styles.

Q: Which specific types of Egyptian artifacts were most influential?

A: A wide range of Egyptian artifacts profoundly influenced modern artists. Tomb paintings and papyri were crucial for their flat, symbolic use of color, bold outlines, and composite figures. Monumental statuary provided inspiration through its simplified, block-like forms and frontal presentations, conveying timelessness and power. Relief carvings showcased the stylized narrative approach and the use of strong outlines and hierarchical scale. Even everyday objects and intricate hieroglyphic inscriptions, with their geometric precision and symbolic weight, offered a rich vocabulary for artists seeking a new visual language.

Q: What materials did ancient Egyptians use, and how did they contribute to the art's influence?

A: Ancient Egyptians masterfully used a range of durable, locally sourced materials, which profoundly contributed to their art's enduring influence. For sculpture, they favored hard stones like granite, basalt, and diorite, allowing for monumental, timeless forms that resisted erosion and symbolized permanence. This deliberate choice was driven by a desire for their art to last for eternity, directly impacting its perceived timelessness by modern artists. Tomb paintings employed mineral pigments like ochre (red, yellow), malachite (green), and lapis lazuli (blue) mixed with binders, applied to dry plaster (fresco secco) or limestone, ensuring vibrant colors that have lasted millennia. Gold, used extensively in funerary masks and jewelry, symbolized divinity, royalty, and eternity. The inherent durability and permanence of these materials were not merely practical choices; they were deeply symbolic, reflecting the culture's obsession with eternity and the afterlife, ensuring the art would continue to convey its message across vast expanses of time, ready to be rediscovered and inspire future generations seeking their own forms of enduring expression.

Q: How did ancient Egyptian art influence Cubism?

A: Ancient Egyptian art primarily influenced Cubism by offering a powerful precedent for conceptual rather than purely optical representation. Cubist artists were profoundly intrigued by the Egyptian artistic practice of depicting figures from multiple viewpoints simultaneously—for example, showing a frontal torso combined with a profile head and legs. This approach, which conveyed the idea or essence of a figure rather than a single realistic perspective, resonated deeply with Cubism's core goal of breaking down and reassembling objects to reveal their multifaceted nature and underlying geometric structure. Picasso, for instance, was known to have studied Egyptian artifacts in the Louvre and other European museums, recognizing this shared conceptual approach.

Q: Did ancient Egyptian art influence Art Nouveau or Symbolism?

A: Yes, ancient Egyptian art significantly influenced both Art Nouveau and Symbolism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Art Nouveau artists, captivated by its exoticism and linear forms, incorporated Egyptian motifs like papyrus, lotus flowers, and scarabs into their decorative arts, jewelry, and architecture, seeking a new, organic aesthetic. Symbolist artists, on the other hand, were drawn to the mystical and spiritual aspects of Egyptian art, using its potent iconography and sense of the eternal to convey deeper philosophical and psychological truths in their paintings and sculptures. They found in Egypt a rich vocabulary for expressing esoteric ideas and the subconscious, aligning with their focus on internal experiences and dream imagery.

Q: Did ancient Egyptian art influence Art Deco?

A: Absolutely! Ancient Egyptian art had a significant and direct influence on Art Deco in the 1920s and 1930s. The discovery of Tutankhamun's tomb in 1922 sparked a global fascination with Egypt, leading to a surge of Egyptian Revival in design. Art Deco embraced Egyptian motifs like zigzags, chevrons, sunbursts, stylized animal forms (like the sphinx or falcons), and geometric patterns. The monumental scale, symmetry, and sleek, streamlined aesthetic of Egyptian architecture and design resonated perfectly with Art Deco's desire for modernity, luxury, and a sense of timeless elegance.

Q: Which modern artists were influenced by Egyptian art?

A: While not always a direct or overtly acknowledged influence, artists across various modern movements drew inspiration. Pablo Picasso and Fernand Léger (Cubism) found resonance in its conceptual representation and geometric forms. Henri Matisse (Fauvism) shared an affinity for bold, flat colors and simplified figures. Piet Mondrian (De Stijl) found parallels in its underlying geometric order and pursuit of universal harmony. Even later artists like Jean-Michel Basquiat (Neo-Expressionism) show echoes of its symbolic, narrative approach and flattened figures. Many of these artists encountered Egyptian art not just through a casual glance, but through dedicated study in major museum collections like the Louvre and the British Museum, at international world's fairs that showcased non-Western cultures, or through newly published archaeological discoveries and academic studies, which systematically brought these ancient aesthetics into contemporary European consciousness.

Q: What role did museums and exhibitions play in connecting modern artists with Egyptian art?

A: Museums and large international exhibitions played a crucial, often catalytic, role in connecting modern artists with ancient Egyptian art. Major institutions like the Louvre in Paris, the British Museum in London, and the Egyptian Museum in Cairo housed extensive collections of Egyptian artifacts, making them accessible for study by artists across Europe. World's Fairs and colonial exhibitions, despite their problematic context, also displayed Egyptian treasures, bringing these aesthetics into public consciousness and directly exposing artists to non-Western forms. These public and academic displays allowed modern artists to directly study the unique stylistic conventions, conceptual approaches, and symbolic language of ancient Egypt, sparking inspiration and validation for their own revolutionary ideas.

Q: Is ancient Egyptian art considered modern art?

A: No, ancient Egyptian art is unequivocally not considered modern art. Modern art typically refers to art produced from the 1860s to the 1970s, characterized by a deliberate rejection of traditional styles and a fervent focus on experimentation, abstraction, and new forms of expression. Ancient Egyptian art, by contrast, belongs firmly to ancient art history, spanning millennia. However, its aesthetic principles, conceptual approaches to representation, and symbolic power had a significant and undeniable influence on the development and conceptual underpinning of many modern art movements. The appreciation and study of ancient art by modern artists is what truly bridges this vast temporal gap and highlights its profound and lasting impact.

Q: How did religion and afterlife beliefs shape Egyptian art's emphasis on permanence and symbolism?

A: The Egyptian belief in the afterlife and the necessity of ensuring a smooth transition and eternal existence for the deceased profoundly shaped their art. This conviction mandated the creation of durable, permanent art—from monumental statues carved in hard stone to meticulously constructed tombs—designed to last for eternity and serve as vessels for the soul (Ka and Ba). Symbolism was paramount: colors, motifs (like the Ankh for life, scarab for rebirth), and hieroglyphic texts were precisely chosen to invoke divine protection, convey status, and guide the deceased, ensuring cosmic order and spiritual well-being. This deep functional and spiritual purpose meant art was never merely aesthetic; it was an essential tool for navigating the cosmos, an intention that, in its pursuit of profound meaning and enduring impact, resonated with many modern artists seeking similar depth in their own work.

Conclusion: The Ever-Present Past and the Artist's Hand

So, there you have it. A whirlwind tour through millennia, proving that art, much like a good story or a persistent memory, never truly dies. It simply changes clothes, finds new voices, and reinterprets ancient wisdom for a contemporary audience. We’ve seen how ancient Egypt's enduring principles of composite representation informed Cubism's deconstruction of form, how its symbolic and bold use of color prefigured Fauvism's emotional explosions, how its meticulous geometric order resonated with De Stijl's quest for universal harmony, and how its powerful iconography continues to empower the narratives of Neo-Expressionists like Basquiat. We've also touched on the broader principles of stylization, monumentality, and the deep cultural imperative for permanence, driven by spiritual beliefs, that captivated these modern minds.

For me, seeing these profound connections isn't just an academic exercise; it's a deeply personal and profound reminder that we are all part of a larger human narrative, constantly building on what came before. It makes me feel less alone in my own creative struggles, knowing that artists throughout history have been grappling with similar questions, seeking similar truths, finding similar answers, even if they were separated by oceans of sand and eons of time. It reinforces my belief that art is a continuous conversation across ages, and that even in the most abstract forms, we are often echoing the profound simplicity and power of the past. So, what ancient echoes do you hear in the art around you, or perhaps even in your own creative expression? Maybe, like me, you'll discover that the "secret handshake" between distant epochs is more vibrant and present than you ever imagined, still passing notes and nudges across the ages. It's certainly something I channel into my own work, where ancient whispers often inform modern hues. I invite you to explore this living legacy further on my art for sale page, or discover more about my personal artist's journey. And as you reflect on these connections, perhaps you'll start to see your own creative journey not as an isolated path, but as a continuation of this incredible, timeless conversation, a personal echo in the grand, unending gallery of human expression.