The Slippery Slope: My Thoughts on the Edge Between Craft and Fine Art

Okay, let's talk about something that ties my brain in knots sometimes – specifically, the moment I saw a stunningly intricate ceramic piece in a high-end gallery last month, priced like a mid-career painting. It wasn't just beautiful; it had presence, it made me think. It felt like it possessed a conceptual depth and material mastery that transcended mere function, demanding contemplation just like any painting or sculpture I'd encounter. The piece itself was a large, hand-built vessel, its surface etched with patterns so fine they looked like lace, glazed in a way that made the clay seem to glow from within. Seeing it there, on a pristine white pedestal, under gallery lights, felt like a direct challenge to every old definition I carried. And boom, the old 'craft' vs. 'fine art' debate flared up in my head again. Is the line between craft and fine art real, helpful, or just a historical hangover? It feels a bit like trying to nail jelly to a wall, doesn't it? One minute you think you've got it figured out – craft is useful, art is... well, art – and the next minute, that ceramic piece, or maybe a painting that feels incredibly crafted, makes the whole definition go blurry. This article is my attempt to untangle that knot, exploring the history of this divide, why it's blurring today, and what factors truly matter when we look at a piece of creative work.

I spend my days surrounded by paints, canvases, digital tools – things that eventually become artworks you can find here. But the process often feels intensely practical, skill-based... dare I say, crafty? I remember spending hours meticulously preparing digital files for printing, adjusting colors pixel by pixel, a process that felt less like spontaneous expression and more like highly skilled labor. Or the physical act of stretching a canvas, getting the tension just right, a quiet, repetitive task that requires a specific kind of material knowledge. It gets me thinking about these labels we use and whether they actually help us understand anything, or just create unnecessary boxes we feel compelled to fit things into. Have you ever felt that way about something you create or appreciate? It's confusing, right? Like trying to explain your favorite obscure music genre to someone who only listens to the radio.

The Old Labels We Inherited (and Why They Feel Dusty)

Traditionally, the separation went something like this, often reinforced by the very institutions meant to champion creativity and the thinkers of the time, including the powerful Salon system and Art Academies. These institutions held significant sway over who was exhibited, who received patronage, and what was taught, effectively codifying a hierarchy:

Fine Art: Think painting, sculpture, maybe high-concept photography. Supposedly created primarily for aesthetic and intellectual purposes. It's meant to be contemplated, to evoke emotion, to make you think. Think Picasso or Rothko. The emphasis is often on the concept or expression over pure technical skill (though skill is usually there!). High-concept photography, for instance, might prioritize the idea or social commentary behind the image over technical perfection or traditional subject matter, perhaps using unconventional subjects or presentation methods.

Craft: Think pottery, weaving, woodworking, glassblowing. Often associated with functionality – a beautiful mug, a woven blanket, a sturdy chair. The emphasis is traditionally seen as being on skill, material mastery, and often, tradition or established techniques.

Sounds simple enough on paper. But reality, as usual, is far messier. I mean, is the skill in carving a woodblock inherently less artistic than the skill in applying paint? My gut says no, but the historical labels often implied otherwise. This traditional view also often placed craft in a hierarchical position below fine art, a notion that feels increasingly outdated today.

History's Role in Drawing the Lines

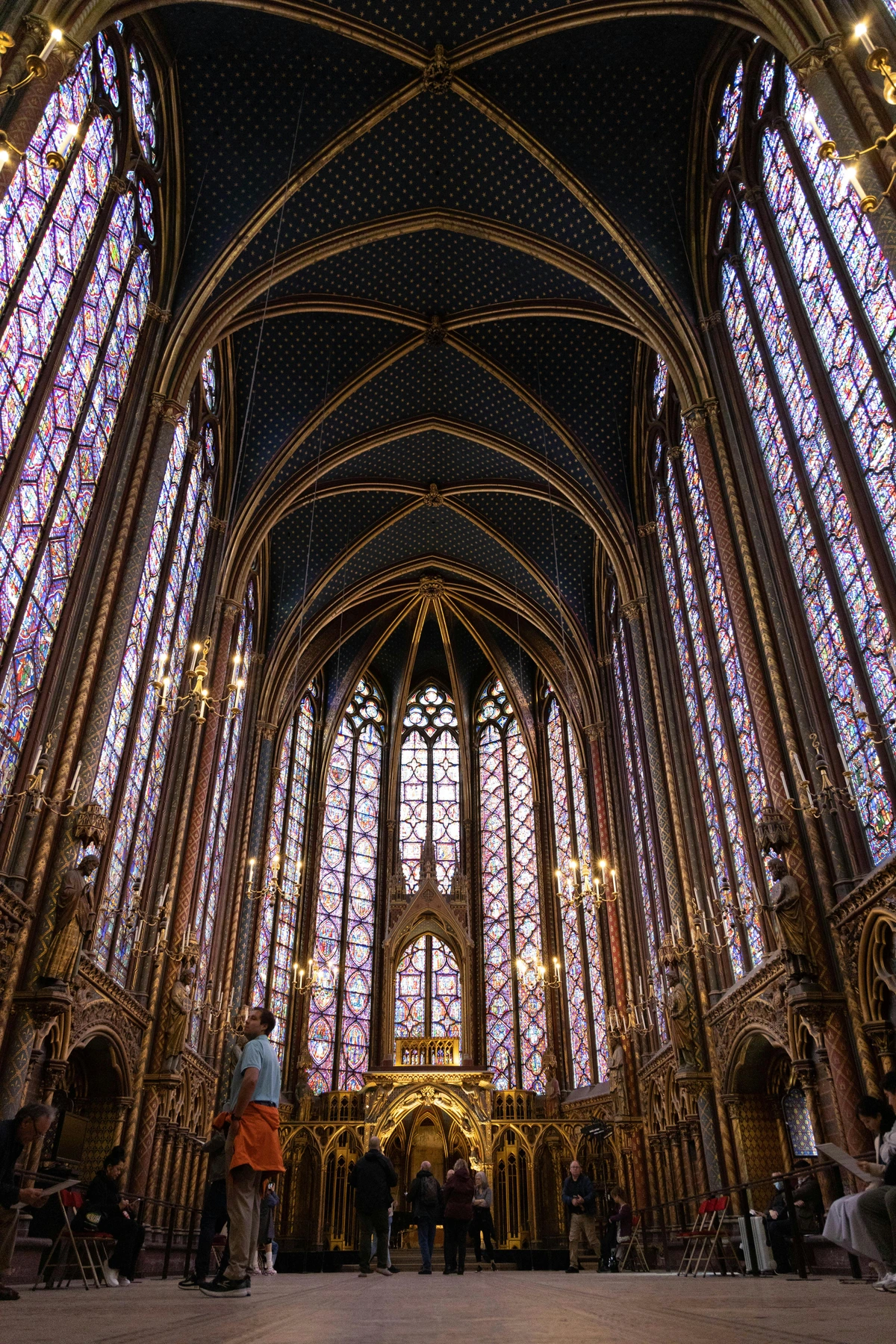

This hierarchy wasn't always a thing. If you look back far enough in art history, the distinction was much fuzzier. Before the Renaissance, the creation of beautiful, skilled objects often happened within systems like guilds and apprenticeships, where mastery of technique and material was paramount, and the line between utility and beauty was thin. Think medieval stained glass or illuminated manuscripts – incredible skill, often functional (telling stories, decorating sacred spaces), and undeniably art. Can you imagine telling a medieval artisan their stained glass wasn't 'real' art because it served a purpose beyond pure aesthetics? It seems absurd now, but that shift in thinking happened.

Consider the intricate metalwork of a medieval reliquary, the complex patterns of a tapestry, or the delicate brushwork in an illuminated manuscript – these were objects of immense skill, often serving religious or practical functions, yet imbued with profound aesthetic and symbolic meaning. The makers were highly respected artisans, and the idea of a rigid 'art' vs. 'craft' divide simply didn't exist in the same way. Guilds, like those for goldsmiths, weavers, or stonemasons, were powerful bodies that ensured quality, trained apprentices, and maintained high standards of craftsmanship. These artisans were not seen as mere laborers but as masters of their trade, creating objects that were both useful and beautiful, often for wealthy patrons or religious institutions.

The big split arguably gained steam around the Renaissance. This era saw the rise of the individual 'genius' artist, often from more privileged backgrounds, and the establishment of Art Academies and the Salon system. These institutions codified painting, sculpture, and architecture as the 'major' arts, implicitly relegating everything else – like textiles, ceramics, and metalwork – to 'minor' or 'decorative' status. This was often framed through the lens of the 'liberal arts' (intellectual pursuits) versus the 'mechanical arts' (manual labor). Thinkers like Leon Battista Alberti and Giorgio Vasari helped cement this idea. Alberti, for instance, emphasized the intellectual foundations of painting, linking it to geometry and history, firmly placing it among the liberal arts and elevating the painter's status beyond that of a mere manual laborer. Vasari's biographies celebrated the 'divine' genius of artists, further reinforcing the idea of the artist as an intellectual creator distinct from the skilled artisan. Painting and sculpture, involving geometry, anatomy, and perspective, were seen as intellectual endeavors, firmly placing them in the former category, while crafts, relying heavily on manual skill, were placed in the latter. It was a conscious effort to elevate the status of the artist from skilled artisan to intellectual creator, partly driven by artists seeking higher social standing and patronage from wealthy elites who valued intellectual pursuits. It's a bit like saying the architect designing the building is the 'artist,' but the skilled stonemason carving the intricate details is 'just' a laborer – a distinction that feels increasingly unfair the closer you look.

It's worth noting, too, that many traditional craft forms, particularly those involving textiles or ceramics, were historically associated with domesticity and 'women's work,' which unfortunately contributed to their lower status in the male-dominated art world hierarchy. Crafts like quilting, embroidery, and lacemaking, often requiring immense skill and patience, were frequently dismissed as mere hobbies or domestic chores rather than serious artistic pursuits. For example, needlework, despite its incredible technical complexity and potential for intricate design and storytelling, was often relegated to the realm of 'accomplishments' for women rather than being recognized as a significant art form by the established male art world. Even within the realm of craft, there were historical hierarchies; goldsmithing, for example, often held a higher status than weaving or pottery, reflecting societal values and the perceived preciousness of materials. The materials themselves played a role – precious metals and marble were often seen as inherently more 'noble' than clay or fiber. Other forms like basketry, folk art, or even certain types of furniture making were often pushed even further down the hierarchy, sometimes not even considered 'craft' in the elevated sense, but simply utilitarian production.

Later, the Industrial Revolution further solidified the divide, contrasting mass-produced goods (seen as purely functional, lacking the 'artist's hand') with unique, 'artistic' creations. The rise of factories meant that skilled manual labor, once highly valued, was increasingly seen as less significant than the conceptual work of the 'artist' creating a unique object, or the designer creating a prototype for mass production. This era also saw the emergence of design as a distinct field, often focused on both form and function for mass production, occupying a space separate from both traditional craft and fine art. Think of a Bauhaus teapot by Marianne Brandt – it's functional, mass-producible, but its form is undeniably artistic, sitting right on that edge. Design schools often emerged from or alongside industrial needs, further separating 'design' (for industry) from 'craft' (traditional handwork) and 'fine art' (gallery-focused creation).

Movements like the Arts and Crafts movement, championed by figures like William Morris and John Ruskin, pushed back against industrialization and the devaluation of skilled handwork. They advocated for the integration of art into everyday life through beautifully made objects, directly challenging the idea that art belonged only in galleries and that functional items were inherently less valuable. This movement was a crucial early step in questioning the established hierarchy and had a lasting impact on design education and the appreciation of applied arts. Following this, the Art Nouveau and Art Deco movements in the late 19th and early 20th centuries further blurred the lines, explicitly seeking to integrate artistic design into everyday objects, architecture, and decorative arts. Art Nouveau, with its organic, flowing lines, and Art Deco, with its geometric forms and luxurious materials, both elevated furniture, jewelry, ceramics, and architecture to a high aesthetic level, challenging the notion that beauty and artistic merit were exclusive to painting and sculpture.

However, the 20th century, with the rise of Modern Art and later Contemporary Art, really threw a spanner in the works. Postmodernism, in particular, delighted in challenging hierarchies, embracing kitsch, and blurring boundaries between 'high' and 'low' culture, which naturally extended to the art/craft divide. Artists started questioning everything:

- What materials could be used? (Suddenly, 'craft' materials were fair game, sometimes even before the major Studio Craft movement. Think of Meret Oppenheim's fur-covered teacup, which used everyday, tactile materials in a surrealist context, challenging traditional notions of sculpture and preciousness. Or the use of collage and found objects in Dada and Surrealism, directly incorporating 'non-art' materials and techniques, blurring the lines between painting, sculpture, and assemblage.)

- What was the role of skill versus idea? (Conceptual art – where the idea behind the work is considered paramount, sometimes even more than the physical object itself – enters the chat. This directly challenged the traditional craft emphasis on material mastery by suggesting the thought was the primary artwork, not necessarily the skilled execution). It's funny how the pendulum swings – from valuing only intellectual 'liberal arts' over manual skill, to valuing the idea over the skilled execution!

- What even is art? (A question Duchamp lobbed like a grenade with his readymades – everyday objects presented as art).

This constant questioning chipped away at the old certainties. The mid-20th century Studio Craft movement saw makers like Peter Voulkos (ceramics) and Sheila Hicks (textile art) consciously using craft materials and techniques to create expressive, sculptural works intended for contemplation, directly challenging the established hierarchy. Textile art, once firmly in the 'craft' camp, now hangs proudly in major museums. Ceramics command fine art prices. The lines haven't just blurred; they've often been erased and redrawn, sometimes kicking and screaming. The rise of new media like photography and film also challenged traditional material hierarchies and definitions of skill, adding further complexity to the landscape.

It's also worth remembering this sharp art/craft divide is largely a Western construct. Many other cultures throughout history haven't drawn such a rigid line, seamlessly integrating aesthetics, skill, and function in objects of daily or ritual use. This global perspective highlights how arbitrary the Western division can be. I mean, have you ever seen a beautifully crafted piece of traditional Japanese pottery or an intricately woven African textile? They effortlessly combine function, incredible skill, and profound aesthetic and cultural meaning in ways that make the Western categories feel... well, a bit silly, frankly. The Japanese Mingei movement, for instance, explicitly celebrated the beauty and skill found in everyday folk crafts, elevating the anonymous craftsman and functional objects to a level of profound aesthetic appreciation, directly counter to the Western hierarchy. Indigenous American pottery, weaving, and beadwork, or the complex geometric patterns in Islamic art and architecture (applied to everything from mosques to metalwork), are other powerful examples where the Western distinction between 'fine art' and 'craft' or 'decorative arts' simply doesn't apply in the same way; skill, beauty, function, and meaning are intrinsically linked. Consider the work of contemporary Indigenous artists who use traditional techniques like basket weaving or beadwork to create powerful, conceptually driven pieces that address history, identity, and social issues, seamlessly bridging traditional craft and contemporary fine art concerns.

Picasso himself dabbled in ceramics, challenging the hierarchy simply by engaging with the medium.

So, with that historical baggage in tow, how do we try to make sense of it all today? And where does something like design fit into this picture? Design, often focused on both form and function, occupies a similar space, sometimes seen as distinct from both art and craft, yet sharing characteristics with both. The rise of 'design art' or 'collectible design' – high-end, limited-edition furniture or objects that function but are primarily valued for their artistic merit and collectibility – explicitly sits in this liminal zone, blurring the lines even further. It's another layer of complexity in the labels we use.

Let's quickly summarize the historical shift:

Era | Art/Craft Distinction | Emphasis | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Renaissance | Fuzzy | Skill, Material Mastery, Function, Beauty | Medieval stained glass, Illuminated manuscripts, Metalwork, Tapestries |

| Renaissance | Sharpens | Concept, Intellect (Fine Art); Skill, Manual Labor (Craft) | Painting, Sculpture, Architecture (Fine Art); Textiles, Ceramics (Craft) |

| Industrial Rev. | Solidifies | Unique Artistic Creation vs. Mass Production | Unique paintings/sculptures vs. Factory-made goods |

| 20th/21st Cent. | Blurs/Erases | Concept, Material, Context, Intent, Skill | Contemporary ceramics, Textile art, Digital art, Performance art |

So, What Matters Now? Context, Intent, Institutions, and More...

If the old definitions don't quite hold up, what does influence how we perceive something as one or the other today? I suspect it boils down to a cocktail of factors, none of which are definitive on their own:

- Context is King (or Queen): Where is the object displayed and discussed? This is huge. A pot in a craft fair feels different from the exact same pot displayed on a pedestal in a contemporary art gallery. The context shapes our perception and assigns value (both cultural and monetary – see understanding art prices). Imagine a weaver intending only to make a functional, beautiful blanket. If a curator later hangs it on a gallery wall and frames it as a statement on labor and tradition, the context shifts its perceived meaning, regardless of the weaver's original intent. The space itself signals how we should approach the object. And let's be honest, the price tag itself in a high-end gallery also sends a powerful signal, often implicitly labeling something as 'fine art' simply by its valuation.

- Presentation Matters: Closely related to context, but distinct. How is the piece lit? Is it framed? Is it on a pedestal? Is it behind glass? These choices, often made by the artist, gallery, or collector, heavily influence how we perceive the object's status and preciousness. A textile piece framed and spotlit on a gallery wall is presented differently than one folded on a table at a market, even if the context (gallery vs. market) is the same. This deliberate presentation can elevate the perceived 'art' status.

- Institutional Framework & The Market: Art schools, museums worldwide, funding bodies, critics, galleries, dealers, and auction houses have historically played (and sometimes still play) a huge role. Curriculum choices (many art schools now integrate traditional craft disciplines into fine art degrees), exhibition selections (like those in the best modern art museums increasingly featuring fiber or ceramic work), grant criteria, and the very language used by critics and art historians in publications and exhibitions can reinforce or challenge the hierarchy. What gets taught, shown, funded, and written about shapes the narrative and influences public perception. Furthermore, the art market actively participates in this labeling and valuation process. Galleries, for instance, play a crucial role not just in selling work but in building an artist's reputation and positioning their practice within the 'fine art' world through representation, curated exhibitions, and fostering relationships with collectors and institutions. This process directly impacts whether work is seen and priced as 'craft' or 'fine art,' sometimes based on trends or the artist's existing reputation within one sphere or the other. It's a powerful force in shaping these perceptions. Even collectors, through their choices and patronage, influence what is deemed valuable and worthy of collecting, further solidifying or challenging these categories. For instance, many grant applications still require artists to select a primary discipline from a list that often separates 'Craft' from 'Visual Arts,' potentially impacting funding opportunities for artists working in hybrid fields. The language used in museum collection categories or exhibition titles can also subtly reinforce the hierarchy, for example, by categorizing certain works under 'Decorative Arts' rather than 'Contemporary Art'.

- Artist's Intent: What did the creator set out to do? Was the primary goal function, aesthetic exploration, emotional expression, or conceptual statement? And here's where my brain starts to short-circuit – intent isn't always clear or singular, and it can even evolve over time. My intent might be to explore color, but the result could still be a functional object if I painted on a plate. Or an artist might intend to create a functional object with such exquisite skill and unique vision that it transcends mere utility. It's a messy, internal thing that doesn't always align with external labels. Sometimes, the artist's intent is even deliberately ambiguous, leaving the interpretation open.

- Viewer's Perception & Knowledge: Ultimately, we bring our own biases and definitions. What one person dismisses as 'just craft', another might see as profound art. Our cultural background, education, and personal taste play a massive role. Our knowledge of art history, craft traditions, or the artist's broader practice also influences how we interpret a piece. How does it make you feel? Does it challenge you? Does it resonate? This is perhaps the most personal and least controllable factor. A viewer unfamiliar with the history of ceramics might see a pot only as a functional object, while someone who knows the work of Peter Voulkos might immediately recognize it as a significant piece of sculptural art.

- The 'Why' vs. The 'How' (and the 'Craftsmanship'): Fine art often seems more concerned with asking 'why?' – questioning norms, exploring ideas, pushing boundaries. Craft, traditionally, might be more focused on the 'how' – mastering a technique, perfecting a form. But again, this is a generalization that many contemporary makers defy. Furthermore, high-level craftsmanship – the sheer technical skill and mastery of materials – is often highly valued even in works firmly placed in the 'fine art' category. Think of the meticulous detail in a hyperrealist painting or the complex construction of a large-scale sculpture. Skill isn't absent from fine art; its role might be different, sometimes serving a concept rather than being the primary focus, but it's often still crucial. The distinction between 'Craft' as a historical category and 'craftsmanship' as a measure of skill is vital here – you can have incredible craftsmanship in fine art, and conceptual depth in Craft.

- Functionality: While craft is often associated with function, and fine art with non-function, this is a slippery slope. Architecture is functional but often considered art. Design objects blur the lines. Some fine art incorporates functional elements, and some craft is purely decorative. Functionality isn't a reliable divider today. Think of a beautifully designed car or a piece of architectural marvel – they serve a purpose but are widely appreciated for their artistic form and innovation. Even performance art, while non-functional in a material sense, often involves highly disciplined physical 'craft' or skill in the execution of the performance itself, requiring rigorous training and mastery of the body or specific actions.

- The Digital Complication: And what about digital art? This is where things get really interesting and, frankly, confusing for the old definitions. Is coding a website a craft? Is 3D modeling for a print fine art? Is using AI tools to generate imagery something else entirely? These new tools and processes further muddy the already murky waters, challenging traditional notions of 'the artist's hand' and material mastery. Where does the 'craft' lie in purely digital creation? Is it in the coding, the algorithm design, the prompt engineering, the manipulation of pixels? Artists are using generative AI, creating immersive virtual reality experiences, designing interactive installations, and producing digital prints that exist only as files until printed. These processes often involve immense technical skill (a hallmark of craftsmanship) but result in non-physical or easily reproducible outputs (challenging traditional fine art notions of uniqueness and material objecthood). For example, mastering complex 3D sculpting software to create intricate digital models requires a level of technical skill comparable to traditional sculpture, even though the final output might be a digital file or a 3D print. Similarly, writing efficient and elegant code for generative art involves a form of 'digital craftsmanship' that is distinct from, but related to, the manual skills of traditional art forms. The digital realm forces us to reconsider what 'making' means and how skill manifests, pushing the boundaries of both 'art' and 'craft' categories simultaneously. The rise of NFTs (Non-Fungible Tokens) adds another layer, creating artificial scarcity and ownership for purely digital works, forcing the market to grapple with valuing non-physical 'art' in ways previously reserved for unique physical objects. Complex digital painting techniques, motion graphics, or programming interactive installations all require a high level of technical 'craftsmanship' in their respective digital mediums.

- Scale and Reproducibility: Historically, large-scale works were often associated with fine art (monumental sculpture, grand paintings), while smaller, domestic objects were seen as craft. Similarly, fine art traditionally emphasized unique objects (paintings, sculptures), while craft often involved multiples (ceramics, textiles). However, contemporary artists working in craft media often create large-scale installations or sculptures that challenge the scale perception, and with the rise of printmaking, photography, and digital art, reproducibility is common in fine art. Conversely, many contemporary craftspeople create unique, one-of-a-kind pieces. So, while historical biases exist, scale and reproducibility are no longer clear dividing lines.

- Education: The historical separation was reinforced by educational institutions. Art schools focused on painting, sculpture, and theory, while craft schools taught specific material techniques. Today, many art schools integrate traditional craft disciplines into fine art degrees, and craft programs increasingly incorporate conceptual and critical studies, blurring the lines from the ground up. An artist's background – whether trained in a traditional fine art program or a specific craft discipline – can still influence how their work is initially perceived, even if they later move between categories. Thinking about my own art education, I remember distinct departments, but increasingly, students moved between them, and the curriculum started overlapping. It felt like the institutions were slowly catching up to what artists were already doing.

- Narrative and Storytelling: Fine art discourse often emphasizes the conceptual narrative or the story the artist is telling through the work. While craft has always had cultural narratives embedded in tradition and function, the explicit focus on the artist's personal or conceptual story has historically been more prominent in fine art. However, contemporary craftspeople are increasingly foregrounding their intentions, research, and the stories behind their materials and processes, adding another layer of depth that resonates with fine art criteria. This is something I see in my own work; even abstract pieces have a story behind the color choices or the process, a narrative that feels important to share.

- Materiality: Beyond just the technique, the inherent qualities, history, and cultural associations of the materials themselves (the earthy feel of clay, the tactile nature of fiber, the permanence of metal vs. the expressive potential of paint, the perceived nobility of marble) continue to influence how we perceive a work, even as artists actively challenge these traditional associations. Artists working in craft media often deliberately choose materials with specific histories or cultural meanings to add layers of interpretation to their work, a practice common in fine art. The choice of material is often as much a conceptual decision as a practical one.

- Cultural Context: While the Western/non-Western divide is significant, even within a single culture or country, regional craft traditions or specific material practices can be perceived differently. The value placed on a particular type of weaving in one region might differ significantly from another, influencing whether it's seen primarily as a functional item, a cultural artifact, or a work of art. This highlights how localized and specific these perceptions can be. It's a reminder that these categories aren't universal truths but culturally constructed ideas.

- Decorative Arts & Applied Arts: Historically, categories like 'Decorative Arts' or 'Applied Arts' existed somewhat in between fine art and craft, often encompassing objects like furniture, ceramics, glass, and textiles that were both functional and highly aesthetic. Museums often had separate departments for these, reinforcing a hierarchy where they were seen as less significant than painting or sculpture. While contemporary practice has blurred these lines considerably, the legacy of these categories still influences how some institutions and collectors view certain types of work. The term 'Applied Arts' is often used to describe the application of artistic design to utilitarian objects, sitting somewhere between fine art and industrial design, and sharing common ground with craft in its focus on form and function.

- Community and Collaboration: Many traditional craft forms are deeply rooted in community, shared knowledge, and collaborative practices, passed down through generations. This often contrasts with the romanticized image of the solitary 'fine artist' pursuing individual expression. Contemporary artists and craftspeople are increasingly engaging with collaborative models and community-based projects, blurring this distinction and highlighting the social dimensions of making.

- Conservation and Preservation: The materials and techniques used in craft often present unique challenges for conservation and preservation compared to traditional fine art mediums like oil painting or bronze sculpture. Organic materials like textiles or wood can be more susceptible to environmental damage. These practical considerations can sometimes influence institutional collecting practices or the perceived long-term value and permanence of the work, adding another layer to how it's categorized and valued.

It's less about the medium (types of artwork) and more about the conversation the work is part of, the systems it operates within, and how we, the audience, engage with it. It's a complex interplay.

The gallery setting instantly signals 'art' to most viewers, influencing perception.

Contemporary Artists Blurring the Lines

To see this blurring in action, you just need to look at some contemporary practices. Artists are actively dismantling these old walls:

- Grayson Perry: A Turner Prize winner known for his ceramic pots, tapestries, and prints. He uses traditional craft media (ceramics, textiles) to create works that are deeply conceptual, satirical, and autobiographical, explicitly challenging the art/craft hierarchy and the historical association of ceramics with 'minor' arts. His tapestries, for example, use a medium historically associated with domestic craft to explore complex social and political themes, elevating the medium itself.

- Nick Cave (Soundsuits): Creates wearable sculptures made from found objects and craft materials like fabric, beads, and hair. These are used in performance art, blurring sculpture, craft (textiles, assemblage), and performance. His work uses craft techniques to create objects for a non-traditional art form (performance).

- El Anatsui: Transforms bottle caps and other discarded materials into large-scale, shimmering textile-like sculptures, elevating everyday 'craft' materials (metal, assemblage) to monumental fine art status. His work is often displayed in major museums and galleries worldwide, demonstrating how material can be recontextualized.

- Ai Weiwei: While known for many things, his use of traditional Chinese porcelain and wood carving techniques in conceptual and politically charged installations directly engages with and subverts traditional craft contexts (ceramics, woodworking). His sunflower seeds installation, made of millions of porcelain seeds produced using traditional techniques in Jingdezhen, is a prime example of using specific cultural craft skill for a massive, conceptual statement.

- Dale Chihuly: Known for his large-scale, elaborate glass sculptures and installations, pushing the boundaries of glassblowing from a traditional craft into monumental, often site-specific, fine art (glass). He takes a traditional craft technique and applies it on an unprecedented scale for purely aesthetic impact.

- Wendell Castle: Created sculptural furniture that blurred the lines between furniture design, craft (woodworking), and fine art sculpture, challenging the notion that functional objects couldn't be high art. His pieces function as furniture but are primarily valued as unique sculptures.

- Magdalene Odundo: A ceramic artist whose elegant, hand-built vessels are displayed and collected as fine art, valued for their form, surface, and conceptual depth, not just potential function (ceramics). Her mastery of traditional techniques results in objects of profound sculptural presence.

- Marina Abramović: While primarily a performance artist, her work often involves intense physical endurance and mastery of the body, sometimes incorporating objects or environments that could be seen through a lens of material engagement or even 'craft' in the sense of disciplined practice. Her collaborations, like The Artist is Present, involve a form of relational 'making' that challenges traditional object-based art, highlighting the 'craft' of performance itself.

- Kiki Smith: Works across a vast range of media including sculpture, printmaking, drawing, and textiles, often exploring themes of the body, nature, and folklore. Her use of materials like glass, paper, and bronze, combined with her focus on narrative and concept, positions her work firmly in the space where traditional craft techniques meet contemporary fine art concerns.

- Toshiko Takaezu: A key figure in the American Studio Craft movement, known for her closed-form ceramic vessels. While her work is rooted in traditional pottery techniques, her focus on sculptural form, glaze as painting, and the non-functional nature of the closed vessel elevates her pieces to fine art objects, emphasizing contemplation over utility.

- Martin Puryear: Known for his sculptures, often large-scale, that utilize traditional woodworking and craft techniques (like joinery, carving, and basketry) to create abstract forms imbued with deep conceptual meaning, often referencing history, identity, and nature. He elevates traditional craft skills to create complex, thought-provoking fine art sculptures.

- Refik Anadol: A digital artist known for his immersive data sculptures and AI-generated art installations. His work involves complex coding, algorithm design, and data manipulation – a form of digital 'craftsmanship' that results in non-physical or ephemeral artworks, pushing the boundaries of what constitutes 'making' and 'materiality' in the digital age. He's essentially a digital artisan operating in the fine art world.

- Jeffrey Gibson: A contemporary artist of Cherokee and Choctaw descent who uses traditional Indigenous craft materials and techniques, such as beadwork, quilting, and ceramics, to create vibrant, multi-layered works that explore identity, history, and contemporary culture. His work is exhibited in major museums and galleries, demonstrating how traditional craft can be a powerful vehicle for contemporary artistic expression and conceptual depth.

These are just a few examples, but they highlight how contemporary artists are using skill, material, and concept in ways that make the old labels feel increasingly inadequate. It's also worth noting that many contemporary makers are perfectly happy operating within the 'craft' world, pushing boundaries of technique, material, and form without seeking validation from the 'fine art' establishment. They find value and innovation within the rich traditions of their chosen medium, creating objects of incredible beauty and skill that may or may not have a function, but are deeply meaningful within the craft context. These artists demonstrate that the most exciting work often happens right on that blurry edge, borrowing from both traditions, refusing easy categorization.

Contemporary installations often defy easy categorization.

My Own Messy Middle Ground

Looking at my own artistic journey, I've wrestled with this. My work is often abstract, focused on color and emotion – classic 'fine art' territory. Yet, the process involves digital tools (sometimes seen as less 'hands-on'), and the output is often prints, which have their own complex history straddling the line (are art prints a good investment?). I also spend hours on the technical 'craft' of preparing files, choosing papers, and ensuring color accuracy – a process that feels very much like material mastery, even if the 'material' is digital data and ink. There's a specific kind of satisfaction, a deep technical skill, in getting a print to perfectly match the colors and textures I envisioned on screen. It feels just as much like 'craftsmanship' as working with clay or wood. Sometimes I joke that I'm just a highly skilled digital artisan who happens to have feelings and ideas. It's a weird space to occupy, but also kind of freeing. I remember one conversation where I was trying to explain the nuances of digital printmaking – the calibration, the paper choices, the way the ink interacts with the surface – and I could see the other person's brain trying to fit it into a neat box. Is it photography? Is it painting? Is it design? It's often easier just to say, "It's art," and let the work speak for itself, but the internal debate about the 'craft' of it is always there. It makes me wonder if my own art school curriculum, despite its modern leanings, still carries some of that old bias, subtly valuing the 'idea' over the 'making', even when the making is incredibly complex.

Does it matter if someone sees the 'craft' in my digital manipulation or the 'art' in the final emotional impact? Honestly, I try not to worry about the label too much. I focus on making work that feels authentic and connects with people. Whether it hangs in a home via my online shop or eventually finds its way into a space like my own little museum project here in 's-Hertogenbosch, the goal is the connection, not the category. I think many contemporary makers feel this way. The most exciting work often happens right on that blurry edge, borrowing from both traditions, refusing easy categorization.

Does the Distinction Even Matter Anymore?

This is the million-dollar question, isn't it? (Or perhaps the ten-thousand-dollar question, depending on whether it's labelled 'art' or 'craft' – a little art market humor there). In some ways, yes, the distinction still has real-world consequences:

- Market Value: Generally, pieces labelled 'fine art' command higher prices. See how much original art costs. It's a market reality, fair or not, and influenced by the institutional factors we discussed. Auction houses and the secondary market play a significant role in solidifying the 'fine art' label and its associated value, often influenced by factors like provenance and exhibition history.

- Institutional Recognition & Funding: Museums and art galleries still have biases, though they are evolving. Getting a show or funding can sometimes depend on fitting into the 'right' category, although this is thankfully becoming less rigid. Many grant applications still require artists to select a primary discipline, and the categories often reflect the old hierarchy, impacting who gets funded and for what kind of work. The language used by critics and art historians in publications and exhibitions also reinforces or challenges the hierarchy.

- Critical Discourse: The language used to discuss craft and art can differ, sometimes subtly valuing conceptual depth over technical mastery, or vice versa. This is slowly changing as critics grapple with the blurred lines.

- Emotional Impact on the Creator: While ideally, the label shouldn't matter, being called an 'artist' often carries a different societal weight and perceived status than being called a 'craftsperson,' which can impact an individual's sense of validation and professional identity.

But in terms of the inherent quality or impact of a work? I'm increasingly convinced the distinction is becoming irrelevant, even unhelpful. Good work is good work. Skill is valuable, whether it's in service of function or concept. Expression can be found in a perfectly thrown pot just as much as in a sprawling canvas.

Maybe the focus should shift from 'Is it craft or art?' to 'Is it compelling? Is it skillful? Does it move me? Does it make me think?' That feels like a more productive conversation. It's less about the box and more about the experience. It's a bit funny, isn't it, how much energy the art world expends on these definitions when the actual creative act and the viewer's experience are so much more fluid and personal.

Skill, expression, material – does the label matter more than the impact?

FAQ: Navigating the Craft vs. Art Maze

Q: Can something be both craft and fine art?

A: Absolutely! Many contemporary artists intentionally blur these lines, using craft techniques to create conceptual fine art, or elevating functional objects to gallery status through exceptional skill and unique vision. The boundaries are porous. Functionality isn't a strict barrier; architecture is functional but often considered art, and many design objects blur the lines. Some fine art incorporates functional elements, and some craft is purely decorative.

Q: Is fine art 'better' than craft?

A: Not inherently. This is a historical bias, often tied to class, gender, and the perceived intellectual vs. manual nature of the work. Quality exists in both fields. A poorly executed painting isn't 'better' than a masterfully crafted piece of furniture. Value is subjective and depends on what criteria you prioritize (skill, concept, beauty, function, originality).

Q: Does using traditional craft materials automatically make something 'craft'?

A: Not anymore. Artists use clay, fibers, wood, glass, etc., to create works shown in the finest art galleries worldwide. The how and why it's used, and the context it's presented in, are more important than the material itself.

Q: How does functionality play a role?

A: While craft is often associated with function, and fine art with non-function, this is a slippery slope. Architecture is functional but often considered art. Design objects blur the lines. Some fine art incorporates functional elements, and some craft is purely decorative. Functionality isn't a reliable divider today. Think of a beautifully designed car or a piece of architectural marvel – they serve a purpose but are widely appreciated for their artistic form and innovation. Even performance art, while non-functional in a material sense, often involves highly disciplined physical 'craft' or skill in the execution.

Q: How has the internet/social media impacted the distinction?

A: Hugely! Online platforms allow makers of all kinds to bypass traditional gatekeepers (galleries, museums) and reach audiences directly. This has empowered craftspeople to market their work as art and has exposed wider audiences to the incredible skill and conceptual depth present in contemporary craft, further eroding the old hierarchy.

Q: Where can I see examples of work that challenges this divide?

A: Look at contemporary ceramic artists (like Voulkos' legacy, Grayson Perry), fiber artists (Sheila Hicks, Nick Cave, El Anatsui), studio glass movements (Dale Chihuly), artists working with sculptural furniture (Wendell Castle), assemblage, or mixed media. Many contemporary art museums and galleries showcase work that defies easy categorization. Also, explore online platforms like Etsy and Instagram, where makers are directly presenting their work to the world.

Q: As a collector, how should I approach work that sits on this boundary?

A: Focus on what resonates with you. Do you connect with the piece aesthetically, emotionally, or intellectually? Do you admire the skill, the concept, the story? Trust your own response rather than worrying excessively about historical labels. Collect what you love and what speaks to you, regardless of whether it's 'art' or 'craft'. Consider the artist's intent, the quality of execution (craftsmanship!), and its place within contemporary dialogues if investment is a factor (researching artists is always key).

Q: Does the scale of a piece influence whether it's seen as art or craft?

A: Sometimes, yes. Historically, large-scale works were often associated with fine art (monumental sculpture, grand paintings), while smaller, domestic objects were seen as craft. However, contemporary artists working in craft media often create large-scale installations or sculptures that challenge this perception, using scale to demand attention and elevate the work's status.

Q: How does the uniqueness or reproducibility of a piece affect its categorization?

A: Traditionally, fine art emphasized unique objects (paintings, sculptures), while craft often involved multiples (ceramics, textiles). However, with the rise of printmaking, photography, and digital art, reproducibility is common in fine art. Conversely, many contemporary craftspeople create unique, one-of-a-kind pieces. So, while historical biases exist, reproducibility is no longer a clear dividing line.

Q: How has art education evolved regarding this divide?

A: Historically, art schools and craft schools were often separate, reinforcing the hierarchy. Art schools focused on painting, sculpture, and theoretical concepts, while craft schools taught specific material techniques. Today, many art schools integrate traditional craft disciplines into fine art degrees, and craft programs increasingly incorporate conceptual and critical studies. This blurring in education reflects and contributes to the blurring in practice.

Q: What role does narrative or storytelling play?

A: While traditional craft often had cultural narratives, the explicit focus on the artist's personal or conceptual story has been more associated with fine art. However, contemporary craftspeople are increasingly incorporating narrative and conceptual depth into their work, challenging this historical distinction.

Q: What about folk art or outsider art?

A: These categories add another layer of complexity! Folk art and outsider art often exist outside the traditional academic and market structures of both fine art and established craft. They are frequently characterized by self-taught artists, unique personal visions, and a strong connection to cultural traditions or internal necessity rather than market trends. While often demonstrating incredible skill and narrative depth, they challenge the conventional hierarchies and definitions, being valued for their authenticity and raw expression.

Q: How does the concept of 'decorative arts' fit into this?

A: 'Decorative Arts' is a historical category that often included functional yet highly aesthetic objects like furniture, ceramics, glass, and textiles. It traditionally sat below 'Fine Art' in the hierarchy, seen as less intellectually rigorous. While the term is still used, contemporary artists working in these mediums often challenge this historical distinction, creating works for galleries and museums that are valued for their artistic merit rather than just their decorative or functional qualities.

Q: Are there resources to learn more about contemporary craft and artists blurring the lines?

A: Absolutely! Look for museums with strong collections in contemporary craft or design (like the Museum of Arts and Design in NYC or the Victoria and Albert Museum in London). Many contemporary art galleries now feature artists working in these mediums. Online platforms, specialized magazines (like American Craft), and books on contemporary ceramics, textiles, or glass are great resources. Following artists on social media can also offer direct insight into their practice and perspective.

Final Thoughts from the Edge

So, where does that leave us? Standing on a rather wobbly precipice, I suppose, maybe peering into a beautifully crafted, conceptually challenging abyss? For me, the most interesting things happen in this liminal space. It's where tradition meets innovation, where skill serves expression, and where function and beauty can coexist or challenge each other. It's the space where that stunning ceramic piece in the gallery made me pause and rethink everything. It's kind of amusing, really, how much energy the art world expends on these definitions when the actual creative act and the viewer's experience are so much more fluid and personal.

Instead of getting tangled in the semantics of the 'right' label, maybe we should just embrace the richness that comes from both 'craft' and 'art'. Appreciate the mastery of a technique, the power of an idea, the beauty of an object, the emotion it evokes – regardless of the category someone else might assign it. Does clinging to the distinction limit our appreciation, or does it still serve a useful purpose? Or is it just a way for institutions and markets to maintain old power structures? As technology like AI continues to evolve, creating new forms of digital 'craftsmanship' and challenging traditional notions of authorship and material, the lines are only going to get blurrier. What do you think? Let me know your thoughts below!