Still Life Painting: History, Meaning, Techniques & Enduring Appeal

Explore still life painting's profound journey, from ancient symbolism to modern abstraction. Discover its evolving meanings, essential techniques, and timeless appeal through an artist's personal lens.

Still Life Painting: A Journey Through History, Meaning, Techniques, and Enduring Art

When you hear 'still life,' what do you picture? For me, it was always just a bowl of fruit or some carefully arranged flowers. And, honestly, for a long time, I didn't grasp the fuss; I saw beauty, sure, but what was the story? It felt like just... stuff. But as an artist who's spent years wrestling with the silent language of objects, I've come to realize there's an entire universe tucked into those seemingly mundane apples – a rich tapestry of human history, emotion, and philosophical inquiry. Still life painting, as I've discovered, isn't quiet at all; it's a centuries-long conversation, a subtle rebellion against the fleeting nature of existence. So, let's lean in and explore the depths of this captivating genre together, uncovering its rich history, evolving meanings, and essential techniques, tracing its path from the ancient world to its boldest contemporary statements.

The Quiet Revolution: What Even IS Still Life?

At its core, still life painting is the artistic depiction of inanimate objects, deliberately arranged by the artist with a specific intention. Simple, right? But the beauty, and frankly, the genius, lies in how artists choose those objects, arrange them, and then render them with light, shadow, and color. It's not just about copying what's there; it's about imbuing those everyday items with meaning, emotion, or a profound sense of the transient beauty of existence. Think of it as a silent stage where ordinary things become extraordinary actors, each playing a role in a larger narrative that the artist (and you!) get to discover. It’s this intense focus on the 'ordinary' that lets the genre say so much, paving the way for its incredible historical journey, a journey that began long, long ago... By the way, you might sometimes hear still life referred to as "nature morte," especially in French-speaking contexts. Literally meaning "dead nature," this term carries a slightly more melancholic or morbid connotation, often emphasizing the fleetingness of life and the inevitability of decay. While not always applicable to every still life, it highlights a profound philosophical dimension that has permeated the genre for centuries.

A Peek Into the Past: Still Life Through the Ages

Ancient Roots and Medieval Whispers

It’s funny, this fascination with objects isn't new at all. You can trace its roots back to ancient Egypt, where detailed depictions of food and offerings adorned tombs, meant to sustain the deceased in the afterlife. It was a practical, spiritual kind of still life, if you ask me. Then, in Roman frescoes across places like Pompeii, you’d discover stunning trompe l'oeil – that’s a beautiful French term meaning 'deceive the eye' – paintings of everyday items: game, fruit, and wine, looking so real they seemed to jump right off the walls. And even in the humble Christian catacombs, elements like bread and fish subtly hinted at the Eucharist. There’s almost a primal human urge to capture the essence of the things we live with, isn't there? A profound testament to how intertwined objects are with our very existence. During the Middle Ages, even as religious art dominated, you’d often find symbolic flowers or specific objects cleverly integrated into altarpieces, devotional paintings, and especially in the intricate borders of illuminated manuscripts. A white lily wasn't just a flower; it signified purity, often associated with the Virgin Mary. A red rose might embody martyrdom or divine love. We’d see humble household items or tools quietly hinting at a saint's life – perhaps a carpenter’s square for Saint Joseph. This tradition of embedding profound symbolism in everyday objects continued to evolve, and by the early Renaissance, artists like Jan van Eyck masterfully integrated still life elements into their religious works. Think of the hyper-realistic details in his 'Arnolfini Portrait,' where objects like fruit, the dog, and the snuffed candle are not just decorative but profoundly symbolic, deepening the narrative and moral messages. These early, quiet inclusions were telling their own stories, hinting at the profound meaning lurking in the mundane long before still life blossomed into a standalone genre. They were the gentle precursors, a subtle nod to the enduring power of the ordinary.

Global Echoes: The Universal Language of Objects

But wait, before we get too focused on Europe, let’s remember that this impulse to depict inanimate objects isn't solely a Western marvel. Nope, not at all! In fact, the human desire to imbue objects with significance seems to echo across every continent. Artistic traditions across the globe have long found profound beauty and meaning in the portrayal of everyday items, even if they didn't always label it 'still life' in the same way. Just look at the intricate floral arrangements and revered scholar's objects found in Chinese porcelain and ink paintings – a rich heritage stretching back to the Qing Dynasty, where artists meticulously rendered academic tools, ancient bronzes, and symbolic flowers. These weren't mere pretty pictures; they were often philosophical statements on education, wisdom, or the harmony of nature. Or consider the meticulous depiction of ritualistic and domestic items in Japanese ukiyo-e woodblock prints by masters like Katsukawa Shunsho or Utagawa Kunisada, where household objects and symbolic elements conveyed narratives or social commentaries. You'll also find symbolic food items in pre-Columbian pottery from the Americas, or the exquisite textiles and jewelry often meticulously depicted in Indian miniatures, where flowers and domestic items carry deep cultural and emotional resonance. And we can't forget the rich traditions in Islamic art, where beyond intricate geometric patterns, ornate decorative objects and calligraphic elements, often without figural representation, create a spiritual still life of divine order, knowledge, and beauty. Each of these global traditions imbues objects with its own deep cultural significance, adding countless vibrant threads to the universal tapestry of still life. What does this ubiquitous urge to give meaning to the things around us tell us about the human condition, I wonder?

The Dutch Golden Age: When Still Life Shone Brightest

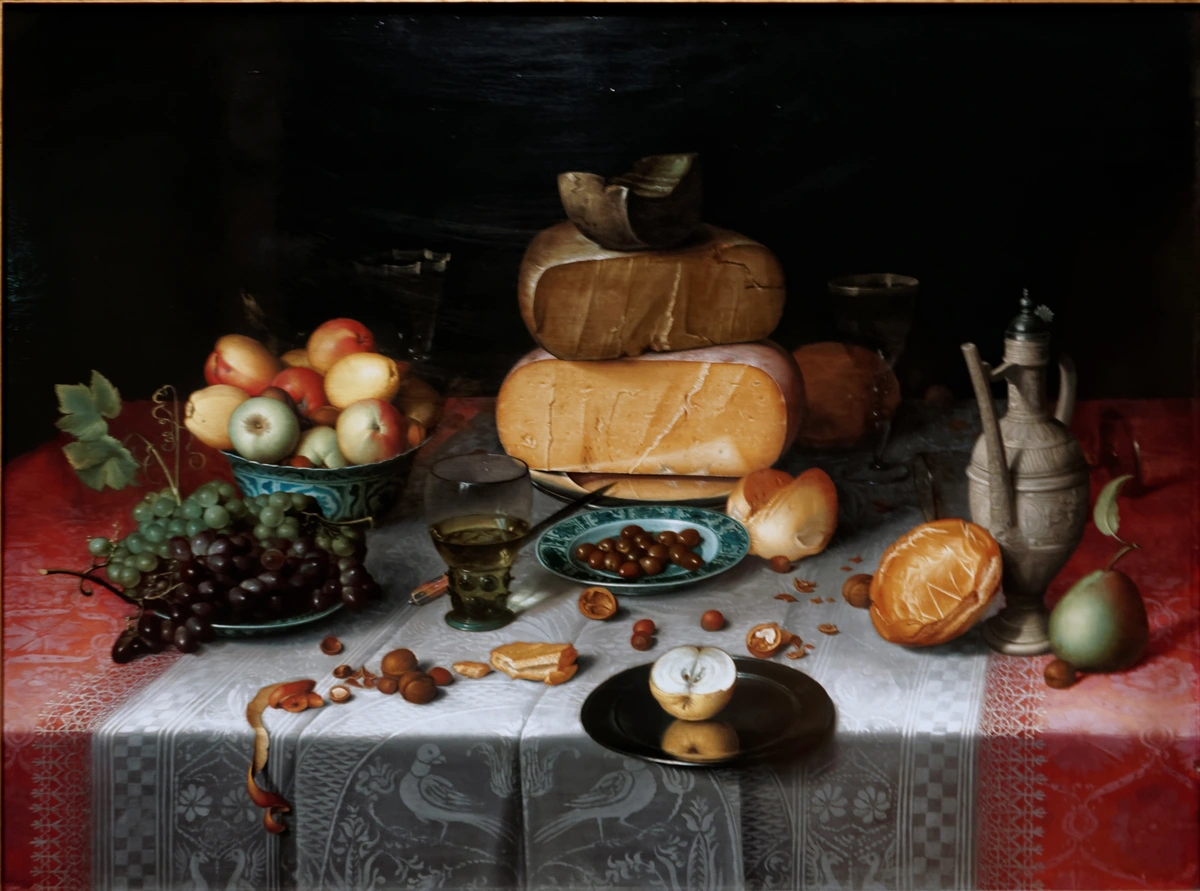

If those ancient examples merely whispered of still life's potential, it was in the vibrant 17th century, with the Dutch Masters, that the genre truly erupted into a distinct and highly celebrated art form. Oh, the sheer opulence! Suddenly, inanimate objects weren't just background fillers; they were the undeniable stars of the show. The burgeoning merchant class in the Netherlands, brimming with new wealth from global trade, eagerly commissioned art that reflected their prosperity. You'd see pieces overflowing with exotic fruits, gleaming silver, delicate glassware, scientific instruments, rare shells, and maps hinting at distant lands. This was, in part, a grand display of status, of course, but it was also a fascinating reflection of a growing scientific curiosity – an era fueled by advancements in scientific illustration and microscopy. When I look at those meticulously detailed botanical specimens, I often think about how these artists, perhaps without even realizing it, were blurring the lines between art and science, indirectly contributing to fields like botany and zoology. Artists like Willem Claesz. Heda became masters of the 'breakfast piece,' depicting lavish meals with such incredible realism you could almost taste the bread. Rachel Ruysch, another powerhouse, created intricate, vibrant floral arrangements that seemed to burst with life, capturing tiny insects and dewdrops with almost scientific precision. And we can’t forget others like Jan Davidsz. de Heem, known for his rich, complex arrangements, or Pieter Claesz., who perfected the monochromatic breakfast piece. It genuinely makes you wonder how much those new scientific lenses influenced their artistic 'lenses,' doesn't it? This era also cleverly integrated still life elements into genre paintings, where everyday scenes often featured meticulously rendered objects that deepened the narrative or established the mood. But it wasn't just about showing off. These paintings were frequently steeped in symbolism, particularly the powerful concept of vanitas. If you're not familiar, vanitas is a Latin word meaning 'emptiness,' and these artworks served as profound reminders of the fleeting nature of life, wealth, and all earthly pleasures. Skulls, snuffed candles, rotting fruit, hourglasses, fragile bubbles… these were all stark memento mori – a Latin phrase meaning 'remember you must die' – placed amidst all the lavishness. It really makes you pause and think, doesn't it? About what truly endures, and what simply fades away with time. If you want to dive deeper into how this period shaped the art world, you might find The Art of Still Life Painting: From Classical to Contemporary a truly fascinating read. What does this intriguing blend of opulence and mortality tell us about our own human desires, and how do we grapple with them today?

Here’s a quick glance at two popular still life sub-genres from the Dutch Golden Age:

Sub-Genre | Typical Subject Matter | Key Symbolic Leanings | Mood/Intention |

|---|---|---|---|

| Breakfast Piece | Opulent meals, bread, cheese, fruit, fine tableware | Abundance, hospitality, simple pleasures, sometimes vanitas | Celebration of daily life, quiet reflection |

| Floral Arrangement | Exotic flowers, insects, dewdrops, wilting petals | Beauty, transience of life, scientific wonder, vanitas | Ephemeral beauty, scientific observation |

credit, licence

The 18th Century: Chardin's Humble Dignity

As the centuries gently unfurled, still life began to shed some of its heavier symbolic cloaks, moving from the grand displays of Dutch opulence to embrace more intimate, personal whispers. And this is key: during this period, the status of still life within academic art circles, though often still considered secondary to the grand narratives of history painting or the prestige of portraiture, began to steadily gain respect. This elevation was thanks in no small part to dedicated specialists who chose still life as their primary focus. Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin in 18th-century France, for instance, brought an unparalleled, humble dignity to everyday objects. He was a master of muted palettes and thick, textured brushstrokes, meticulously focusing on the inherent qualities of surfaces – the rough ceramic of a pot, the soft skin of a peach – with a sensitivity that continues to move me deeply. Think of his iconic painting, 'The Ray,' which transforms a seemingly mundane kitchen scene into a profound, almost dramatic statement. Or his 'Basket of Wild Strawberries,' where the simple arrangement of fruit becomes a quiet meditation on presence and the beauty of the transient. His masterful, quiet compositions subtly paved the way for later artists, particularly the Impressionists, with his revolutionary focus on light and the inherent integrity of everyday forms. Chardin, alongside other specialists like Raphaelle Peale in America, weren't just painting 'stuff'; they were elevating the genre itself to new artistic heights, demonstrating its immense expressive potential. What quiet, profound revolutions were these artists sparking with their unassuming apples and earthenware vases, I wonder? Indeed, the subtle shifts they initiated would soon ignite a much more vibrant, almost rebellious explosion in the century to come.

The 19th Century: Impressionists and Modern Seeds

Then, the 19th century arrived with its vibrant, almost rebellious explosions. The Impressionists, for instance, didn't just paint still lifes; they used them as vibrant laboratories to dissect and explore color, light, and form, often shattering traditional perspective and laying the groundwork for even more radical transformations. Think of Paul Cézanne, whose methodical yet revolutionary approach to fruit bowls and mountains fundamentally questioned how we see reality, directly influencing the Cubists with his geometric reductions. Or Vincent van Gogh, whose emotionally charged sunflowers weren't just flowers but expressions of his soul. Pierre-Auguste Renoir played with light dancing on simple domestic arrangements. Crucially, this era also saw the profound influence of Japonisme – the impact of Japanese art, particularly ukiyo-e woodblock prints, on Western artists. Figures like Edgar Degas and Claude Monet, intrigued by their unique compositions, bold outlines, and flattened perspectives, often incorporated these stylistic choices into their still lifes, opening up entirely new ways of seeing objects. Meanwhile, Paul Gauguin imbued his still lifes with symbolic meaning and rich, flattened patterns, often reflecting his experiences in the South Seas. And then there's Henri Matisse, who wholeheartedly embraced still life, using vibrant, non-naturalistic colors and bold outlines to explore pure emotional expression, rather than strict realism. This was a period of intense artistic experimentation, where the object became less about what it was in a literal sense, and far more about what the artist made of it – their interpretation, their feeling, their unique vision. How did their bold, individual strokes challenge the very idea of what an object is to us, both visually and emotionally? It was these radical questionings that directly paved the way for the even more explosive deconstructions of the Modernists.

Modern Interpretations: Shattering the Stillness

Then came the modernists, and they truly blew everything up. Suddenly, a still life wasn't just about representing reality; it was about interpreting it, dissecting it, or even abstracting it entirely. This was a playground for revolution, where the object became a starting point, not an endpoint.

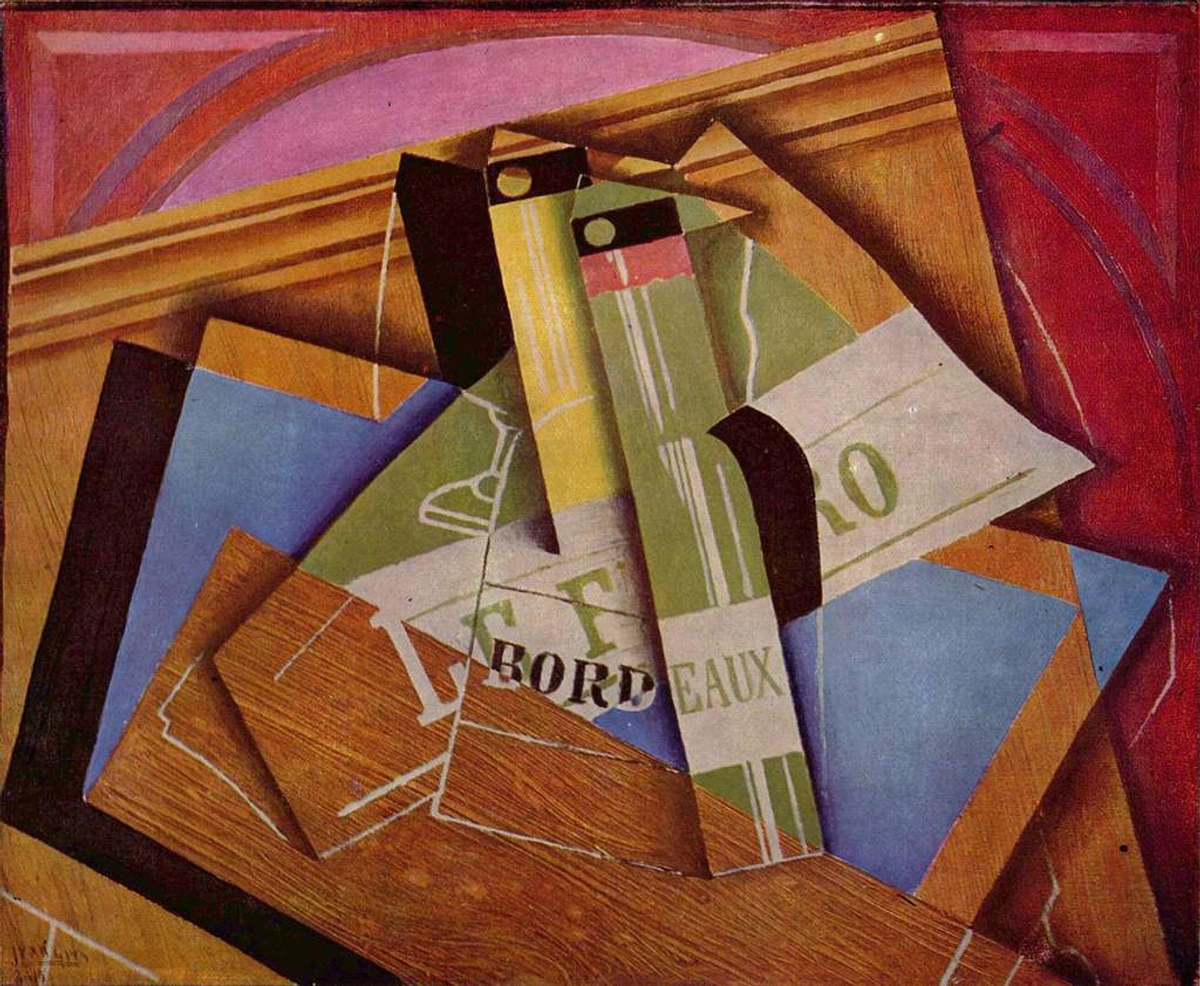

Cubism: Deconstructing Reality

Juan Gris, bless his Cubist heart, wasn't content with just showing you a bottle of Bordeaux on a table. He showed you its essence, from multiple angles at once, fragmenting and reassembling it. It's like your brain trying to piece together a memory – fragmented, yet still undeniably whole. If you're interested in diving deeper into this revolutionary movement, The Ultimate Guide to Cubism is a fantastic resource.

Beyond Cubism: Dreams, Pop, and Abstraction

Beyond the fractured planes of Cubism, other movements truly launched still life into wild, new territories. Surrealism, for example, plunged it into the realm of dreams and the subconscious, where melting clocks (hello, Dalí!) or impossible juxtapositions conjured unsettling, profound new meanings. Closely related, Dadaism, on the other hand, often employed 'found objects' (or objets trouvés) in their anti-art statements, deliberately challenging the very definition of an artwork. For Dadaists, the act of selecting and presenting an ordinary, mass-produced item – like Marcel Duchamp's infamous 'Fountain' – was a still life in itself, making a profound statement about authorship, context, and the arbitrary nature of what society deems 'art.' Then came movements that responded to the changing industrial and consumer landscape. Pop Art redefined still life entirely by elevating everyday commercial objects – think Andy Warhol's iconic soup cans – to high art status, challenging our very notions of what art could be. Even movements like Futurism, with their obsession with speed and dynamism, sometimes used arrangements of objects to explore motion and mechanical forms, capturing the energy of modern life. Fauvism, with its vibrant, non-naturalistic colors, used arrangements of objects not for realism but to explode with intense emotional expression – imagine Henri Matisse's 'Goldfish' or André Derain's 'Still Life with Oranges' where color is liberated. And early Abstract Expressionism? Many of those artists often began with still life arrangements as a formal exercise, a structured starting point, before dissolving into pure abstraction, using objects as a springboard into psychological states and raw emotion. Artists embracing collage, from Picasso's early experiments to contemporary creators, essentially build new still lifes from found fragments, radically redefining composition and narrative. It's fascinating how the invention of photography also fundamentally shifted still life painting. While cameras could capture hyper-realistic representations with ease, painters were, in a sense, liberated from that imperative. This freedom allowed them to explore abstraction, symbolism, and emotional expression more deeply, moving away from purely documentary representation. Today, digital art and AI tools further blur these lines, allowing artists to create entirely fabricated, hyper-real, or even impossible still life arrangements, prompting new questions about reality and authorship. What does this ever-expanding canvas tell us about our ongoing fascination with the 'still' world, even as our tools change?

The Grand Canvas: Exploring Scale in Still Life

And while we’re expanding our view, let’s pause and talk about scale, because it absolutely changes everything. It’s another dimension that significantly impacts how we experience still life. Most still life paintings we encounter are fairly intimate, easel-sized works, isn't that right? They’re designed to draw you in close, inviting a personal, almost whispered conversation where you can appreciate the delicate details – a tiny brushstroke on a grape, the subtle sheen of a silver goblet. But then, you stumble upon a monumental still life, something grand and truly commanding. Imagine a huge canvas overflowing with game, or a vast array of botanical specimens from the Dutch Golden Age, designed to impress and almost overwhelm the viewer. Or leap to the contemporary art world: think of artists like Claes Oldenburg, whose giant soft sculptures of everyday items – colossal hamburgers, immense clothes pins – transform the familiar into something playful yet profound, making us question the mundane. Jeff Koons, too, with his iconic giant balloon dog sculptures, takes commercial objects and inflates them into overwhelming, theatrical spectacles. Contemporary photographers like Sam Taylor-Johnson also explore monumental still lifes, presenting decaying fruit on a grand, confronting scale, forcing an intense dialogue with themes of vanitas. Suddenly, the objects aren't just there to be admired; they become almost overwhelming, demanding your full attention, dramatically changing the entire dynamic of the viewing experience. It's a powerful reminder that even the 'stillest' subjects can exert an enormous presence, and it truly shows how an artist can manipulate our perception through sheer size, forcing us to engage differently with the familiar.

Still Life's Broader Canvas: Beyond Standalone Paintings

It’s also crucial to remember that the spirit of still life reaches far beyond standalone paintings. It permeates so much more! Just think about how a meticulously rendered vase of flowers, perhaps wilting slightly, might subtly set a melancholic mood in a portrait, revealing something about the sitter's inner world. Or consider how domestic objects in a genre painting – a scene of everyday life, like a Dutch interior – can communicate volumes about the characters, their social standing, or their environment without a single spoken word. For example, a strategically placed half-peeled lemon or a tilted glass in a Dutch feast scene can suggest the transient nature of earthly pleasures, even amidst celebration. These clever inclusions deepen the narrative and enrich the context, proving that the power of objects extends far beyond their primary, central depiction. Beyond painting, the spirit of still life has vibrantly expanded into sculpture, installation art, decorative arts, textiles, and even film set design. Consider the way Cubist sculptors fragment and reassemble objects, challenging our perception of form in three dimensions. Or how contemporary artists arrange everyday items – from consumer products to natural elements – to construct entirely new narratives and experiences within a gallery space. Today, the very boundaries of still life continue to delightfully blur. My own work, for instance, often leans deeply into abstraction. I don't find the 'still life' in perfect, photographic representation, but rather in the energetic dance of color and form, the feeling an object evokes, or the raw energy of a captured moment. For me, it's less about 'what is it?' and far more about 'how does it feel?' If you're curious about how I approach composition, especially in abstract pieces, or want to explore how to abstract art, you might want to explore my thoughts on principles of still life composition.

The Artist's Toolkit: Materials and Techniques Through Time

Speaking of how it feels – because that’s really what art is all about, isn't it? As artists reimagined what still life could be, they also relentlessly innovated the very tools and techniques they embraced to bring those visions to vibrant life. The materials themselves underwent dramatic transformations, and sometimes, a seemingly small innovation could unlock an entire new world of expression, allowing for far richer emotional palettes. For instance, the development of more stable blue pigments like ultramarine, or new drying agents for oils, didn't just mean brighter colors; they allowed for greater flexibility, enabling artists to convey deeper melancholia or more vibrant joy with unprecedented control. In earlier periods, egg tempera on wood panels created those incredibly crisp, precise details we see, perfect for delicate allegories and symbolic flowers. But then came the advent of oil paints, granting artists immense flexibility. Crucially, the increasing availability of canvas as a support material also revolutionized still life. Lighter and more portable than heavy wood panels, canvas allowed for larger compositions and greater freedom in brushwork, enabling artists to work on more ambitious scales and explore broader gestures. The Dutch Masters, as we discussed, were virtuosos of glazing – applying thin, translucent layers of paint, almost like layering delicate veils of color, to build up incredible luminosity and depth in their fruit and glassware, making surfaces truly gleam and evoke an almost tangible luxury. They also skillfully used scumbling – lightly dragging opaque paint over a dry layer for a broken, textured effect – to create softer textures, and alla prima (direct, wet-on-wet painting) for fresh, immediate effects. The Impressionists, on the other hand, favored thicker, visible brushstrokes and impasto to capture the fleeting effects of light and texture, often painting rapidly en plein air (outdoors) to catch the moment and express raw sensation. The invention of pre-mixed paints in tubes, for instance, was a complete game-changer, liberating artists from the confines of the studio and enabling them to capture light and color in real-time, directly influencing their still life compositions. As the 20th century dawned, new materials like synthetic pigments and acrylics further exploded the palette, allowing for bolder, more opaque colors and faster drying times, opening vast new doors for the vibrant, expressive still lifes we cherish today. And let’s not forget the expressive freedom offered by mediums like pastels and watercolors, which allowed artists to explore different textures, transparencies, and immediate bursts of color. Beyond painting, printmaking techniques such as etching and lithography also offered artists new, intricate ways to explore still life, enabling incredibly fine detail or broad tonal variations, and crucially, reaching wider audiences through reproducible editions. This constant interplay between artistic intention and the material possibilities utterly fascinates me. I remember once, in my own studio, trying to achieve a particular luminous, almost ethereal effect with a brand-new pigment for an abstract still life, convinced it would be utterly revolutionary. What I ended up with instead was a muddy, lifeless mess – a rather humbling, harsh reminder that even the best tools demand respect and understanding, and sometimes, a good dose of humility from the artist. It taught me invaluable lessons about the relationship between material and intention, especially when rendering the quiet dignity of a simple vase or the fleeting glow on a piece of fruit. From meticulous preparatory drawings to spontaneous, intuitive marks, each era brought its own innovations, giving artists fresh, exciting ways to 'see' and 'show' their chosen objects. It truly is a fascinating, unending dance between the artist, their subject, and the medium itself, continuously pushing the boundaries of what a 'still' object can convey.

Why Do We Care? The Enduring Appeal

So, the big question remains: why has still life endured for so long, compelling so many artists across centuries to meticulously arrange and render inanimate objects? I truly believe it’s because it speaks to something profoundly, universally human: our inherent need to discover meaning and beauty in the everyday. It's an invitation to pause, to truly look at the quiet beauty and profound significance hiding in plain sight within the mundane. It feels like a quiet rebellion against the constant rush of modern life, offering a moment to appreciate texture, light, and the silent, evocative stories objects silently tell – stories that can stir nostalgia, offer deep peace, or even a subtle, poignant anxiety about the swift passage of time. Psychologically, still life can offer a remarkable sense of order and tranquility, carving out a quiet, contemplative space in an often-chaotic world. It can be deeply meditative, a visual anchor in the storm of modern life, fostering a moment of genuine mindfulness and focused presence. Or, as we've seen with vanitas paintings, it can intentionally evoke a powerful melancholy, sharply reminding us of impermanence. Beyond these, still life can tap into our subconscious, gently (or not so gently) reminding us of forgotten memories, or even subtly commenting on themes of domesticity, consumerism, or identity in modern contexts. In a world saturated with constant digital noise, a still life uniquely demands our undivided presence and focused attention. It can also serve as an incredibly powerful vehicle for incisive social commentary or political statements, especially in contemporary art. Think of artists like Subodh Gupta, whose monumental works created from discarded stainless steel utensils in India powerfully critique consumerism and social hierarchies, or photographers who arrange everyday objects to highlight social inequality or urgent environmental concerns. These works transform the mundane into potent symbols, forcing us to confront uncomfortable truths. What's more, these works serve as an incredibly accessible entry point into the vast world of art. Unlike complex historical narratives or highly abstract conceptual pieces, a carefully rendered bowl of fruit or a simple vase of flowers is instantly relatable, inviting viewers to engage and explore deeper meanings at their own comfortable pace. And for many artists, myself undeniably included, still life functions as a fundamental, indispensable exercise, rigorously honing observation skills, refining compositional understanding, and perfecting rendering techniques – it’s a quiet, demanding classroom within the studio, offering a structured yet endlessly creative way to develop a truly personal artistic language. Consider the work of Giorgio Morandi, who spent his entire career painting humble bottles, bowls, and boxes with such quiet intensity that each composition becomes a profound meditation on form, light, and the passage of time – a masterclass in seeing the universe in the subtle relationships of ordinary things. It's fundamental to learning to see as an artist, to truly understand what lies beyond the surface. For me, as an artist, it’s a boundless source of inspiration, an ever-evolving playground for exploring complex compositions and the dynamic dance of color. Perhaps that’s exactly why I find myself gravitating toward everyday objects in my own art. There's just so much latent emotion and potential within them, patiently waiting to be discovered. This journey of discovery, both deeply personal and intensely artistic, has profoundly shaped my perspective, and still life has always been a constant, quiet anchor.

Frequently Asked Questions About Still Life Painting

Okay, let's tackle some of the common questions I hear when I talk about still life. It's a genre that sparks a lot of curiosity, and I love that!

What defines a still life painting?

A still life painting is generally defined as a work of art depicting inanimate objects, which can include natural items (fruit, flowers, dead animals, rocks, shells) or man-made ones (vases, books, jewelry, coins, pipes). The key is that the objects are not living, and they are typically arranged by the artist with a specific intention to convey meaning, beauty, or a particular message. You might also hear the term "nature morte" used, particularly in French, which literally means 'dead nature' and often emphasizes the 'fleetingness of life' aspect, carrying connotations of transience or decay.

What's the difference between still life and trompe l'oeil?

This is a great point because they often overlap! While both involve inanimate objects, still life is the broader genre focused on composition, symbolism, and the artist's interpretation of objects. Trompe l'oeil (French for 'deceive the eye') is a specific technique within art, aiming to create such a realistic illusion that the viewer momentarily believes the depicted objects are real and three-dimensional. So, a trompe l'oeil is often a still life, but a still life isn't necessarily a trompe l'oeil; it might be highly stylized, abstract, or symbolic without striving for perfect illusion.

What is 'vanitas' in still life art?

Vanitas is a specific genre of still life, prominent in 17th-century Dutch art, that uses symbolic objects to remind the viewer of the transient nature of life, the futility of earthly pleasures, and the inevitability of death. Common symbols include skulls, rotting fruit, snuffed candles, hourglasses, and bubbles.

How does still life compare to other art genres, and why was it sometimes considered a 'lower' genre?

Historically, still life was often ranked lower than genres like history painting, portraiture, or landscape. This was mainly because, in academic hierarchies, it was perceived to lack the narrative complexity, human drama, or profound moral content that 'higher' genres were expected to convey. However, this perception began to shift dramatically from the 17th century onwards, as artists like Chardin elevated the genre through masterful technique and profound insights into the ordinary. Modern movements further championed still life, recognizing its immense potential for formal experimentation, symbolic depth, and personal expression, firmly establishing its place in the art world. Today, it stands as a genre capable of profound statements, rivaling any other in its capacity for emotional impact and intellectual inquiry.

Why are still life paintings popular?

Their enduring popularity stems from several fascinating factors:

- Artist Control: They allow artists immense control over every aspect of composition, lighting, and symbolism, making them a powerful vehicle for artistic vision.

- Relatability: The subject matter – everyday objects – is instantly relatable and accessible, inviting viewers from all backgrounds to engage and explore deeper meanings.

- Symbolic Depth: Still lifes often carry rich symbolic or philosophical meanings that resonate with viewers on a deeper, more contemplative level.

- Showcase of Skill: They provide an incredible platform for artists to showcase their mastery in rendering textures, light, and form with breathtaking realism or evocative abstraction.

- Contemplative Beauty: They offer a quiet, meditative beauty that can be deeply moving and provide a sense of calm or reflection in a busy world.

- Conversation Starters: And yes, I've found they still make fantastic conversation starters, prompting discussions about art, life, and meaning!

What are some common challenges artists face when creating still life paintings?

Oh, where to begin! Still life might look 'still,' but it presents its own unique hurdles. Some common challenges include:

- Maintaining Interest: How do you imbue stationary objects with a compelling narrative or emotional resonance to keep the viewer engaged? It's more than just a pretty arrangement.

- Mastering Light: Capturing light that feels alive and uses it effectively to reveal texture and form is incredibly difficult, especially if you're working over multiple sessions and the natural light shifts. I remember struggling for days to get the exact sheen on a polished apple just right – that subtle gradient of light and reflection, without making it look flat, was an artistic puzzle that taught me so much about observation!

- Avoiding Clichés: It's a constant artistic puzzle to avoid predictable, cliché arrangements and instead imbue the setup with a truly personal meaning or unique perspective. It’s about finding that individual voice in the silence of objects, which can be incredibly difficult.

- Compositional Balance: Creating a dynamic yet harmonious composition with a limited set of inanimate objects requires a keen eye and a deep understanding of visual weight and flow.

How has photography influenced still life painting?

Photography dramatically shifted the landscape for still life. Once cameras could capture hyper-realistic representations of objects with perfect accuracy, painters were, in a sense, liberated from that imperative. This freedom allowed them to explore abstraction, symbolism, and emotional expression more deeply, moving away from purely documentary representation. Photography didn't kill still life painting; it revitalized it, pushing artists to find new ways of interpreting the 'still' world and exploring the enduring, subjective qualities of objects. Today, digital art and AI tools further blur these lines, allowing artists to create entirely fabricated, hyper-real, or even impossible still life arrangements, prompting new questions about reality and authorship.

What are the key differences between still life painting and still life photography?

That's a fantastic question, and one I get a lot! While both mediums depict inanimate objects, painting offers the artist complete control over every element – color, texture, light, perspective – allowing for exaggeration, abstraction, and the infusion of emotional or symbolic meaning far beyond mere representation. It's like building a world from scratch. Photography, on the other hand, excels at capturing a precise moment and playing with light as it naturally exists, often focusing on hyper-realism or conceptual arrangements within the frame of existing reality. It's the difference between shaping reality and carefully selecting and framing a compelling slice of it.

How does still life evolve with digital art and AI?

With the advent of digital tools and artificial intelligence, still life has entered an exciting new frontier. Digital artists can construct entirely fabricated, hyper-realistic, or even impossible arrangements of objects, pushing the boundaries of what 'reality' means in art. AI, on the other hand, can generate countless variations of still life compositions, challenging traditional notions of authorship and creativity. These technologies further liberate artists from purely representational constraints, allowing for boundless formal experimentation and conceptual exploration, constantly redefining the genre for the 21st century.

How can I start creating my own still life art as a beginner?

Starting your own still life journey is wonderfully accessible and one of the best ways to train your artistic eye! Simply grab some everyday objects – a favorite mug, a piece of fruit, a simple vase, or even a collection of pebbles – and arrange them on a table or surface. Don't overthink it; just begin by truly observing the interplay of light and shadows. Focus on understanding simple shapes and the relationships between objects. Don't be afraid to experiment with different materials, whether it's pencils, charcoal, pastels, or paints. The key is consistent observation and enjoyable practice, allowing your unique perspective and emotional connection to the objects to organically emerge. It’s a fantastic, low-pressure way to develop your artistic eye and deepen your connection with the world around you.

What role does the artist's personal connection play in still life art?

For me, and I believe for many artists, the personal connection to the objects chosen for a still life is absolutely central. It transforms a mere arrangement of 'things' into a deeply felt narrative. Whether it’s an heirloom, a found object from a memorable trip, or simply an item whose form or color captivates me, this personal resonance injects the artwork with a unique emotional truth. It's not just about rendering an object; it's about conveying the stories, memories, or feelings that object evokes within the artist, inviting the viewer to connect on a more intimate, human level. It’s what makes a still life feel alive, even when its subjects are, well, still.

My Final Thought

So, next time you see a painting of a seemingly ordinary object – whether it’s a vibrant, abstract interpretation or a meticulously rendered classical piece – pause for a moment. What story is it trying to tell you? What quiet beauty is hiding in plain sight? Remember how we traced still life from ancient offerings to global echoes, Dutch opulence, Chardin's quiet dignity, the Cubists' shattered realities, and then into the abstract expressions of today, exploring how even scale transforms meaning. It's clear that still life isn't still at all; it's a dynamic, living genre, constantly bursting with life, history, and endless possibilities for connection, if you just take the time to really look. My own journey as an artist has been profoundly shaped by these silent conversations with objects, and I hope this exploration inspires you to start seeing your own everyday surroundings a little differently too. If this journey has sparked your curiosity for more art that challenges perceptions, or if you'd like to delve deeper into these 'still' conversations, I warmly invite you to explore my own abstract interpretations through my art for sale, or perhaps visit my museum in 's-Hertogenbosch where you can experience the vibrant dialogues my work creates with the world. And don't forget, the best way to understand still life is to engage with it yourself – grab a pencil or brush, arrange a few simple objects around you, and start your own conversation with the 'still' world. It's an endlessly rewarding journey.