Beyond the Square: Suprematism's Enduring Echoes in My Abstract Art

Dive into my personal journey with Suprematism, exploring its spiritual rebellion, foundational geometric purity, and unexpected influence on modern design, contemporary artists, and my own vibrant abstract practice today.

Beyond the Square: Suprematism''s Enduring Echoes in My Abstract Art

I've often wondered about the invisible currents that steer an artist's hand, those profound influences that embed themselves so deeply they feel like innate truths. It’s like trying to remember the exact moment you learned to swim; the knowledge is there, but the origin is blurred by countless strokes. For me, one such powerful, unseen current is Suprematism. You might associate it with rigid squares and stern, unyielding lines, perhaps even a bit intimidating at first glance. But to me, it embodies a profound, almost spiritual, rebellion—a fierce rejection of the noise, the illusion, and the suffocating conventions of its time, all to arrive at the very essence of art. This profound rebellion wasn't merely aesthetic; it was a spiritual quest to strip away the illusion of the material world, to reach a 'pure feeling' where art became a direct conduit for universal truths, unburdened by narrative or recognizable forms. This isn't just art history; this is the quiet hum beneath the surface of my own vibrant, often gestural, abstract world, subtly guiding my hand even when my canvas is miles away from a pure geometric form. In this piece, I want to pull back the curtain on how Suprematism, often seen as a historical footnote, has subtly yet powerfully shaped my vibrant, gestural abstract world and continues to inspire my artistic journey. If you're curious about the bigger picture, you might enjoy diving into the history of abstract art to see where it all began.

Back to Basics: The Birth of Suprematism and the Black Square

My first encounter with Malevich's Black Square was, I confess, a bit anticlimactic. "That's it?" I thought, with the casual cynicism of someone who hadn't yet learned to look beyond the obvious. It was much like the time I confidently declared a minimalist piece of furniture was 'just a box' only to later realize its elegant functionality in my tiny studio – utterly missing the point until a moment of profound clarity hits.

But then, you sit with it. You let it breathe. And slowly, the profound simplicity reveals itself. Malevich wasn't merely painting a square; he was declaring war on objective representation, on the very idea that art must serve a narrative or depict the visible. Amidst the revolutionary fervor of early 20th-century Russia, he sought to create what he called “non-objective art”—a pure, autonomous art form liberated from the burden of the real world. He termed it "zero form," a point of pure feeling, where art was freed from all earthly reference, becoming a direct conduit for the soul. It was like an artist stripping their studio bare, removing every unnecessary tool, every distracting color, until only the most fundamental element remained—the canvas itself, waiting for a single, potent mark. This wasn't just about geometry; it was about spiritual liberation, a quest for an absolute, universal aesthetic. Along with his iconic Black Square, Malevich explored these fundamental principles in works like "Black Circle" and "Black Cross," alongside other pioneering Suprematists such as Olga Rozanova and Ivan Klyun, who further pushed the boundaries of this stark, yet deeply resonant, visual language. They were crafting a new alphabet for visual expression, born from the revolutionary spirit of their time. It pushed the boundaries of what is design in art and cultivated a deeper appreciation for the symbolism of geometric shapes in abstract art. Malevich's audacious act, and the principles he laid bare, began a ripple effect that would redefine art for generations.

Ripples Through Time: Suprematism's Echoes in Modern Movements

But did these radical ideas stay confined to Russia, or did they, like whispers on the wind, travel across borders and ignite new artistic revolutions? Suprematism didn’t just appear in a vacuum and then vanish. Its radical ideas spread like intellectual wildfire, inspiring artists and thinkers across Europe. If Malevich was the lone, intense scientist creating a new element in his lab, then movements like De Stijl in the Netherlands and the Bauhaus in Germany were the engineers who took that element and started building entirely new structures with it. Want to know more about that period? Check out the history of modern art.

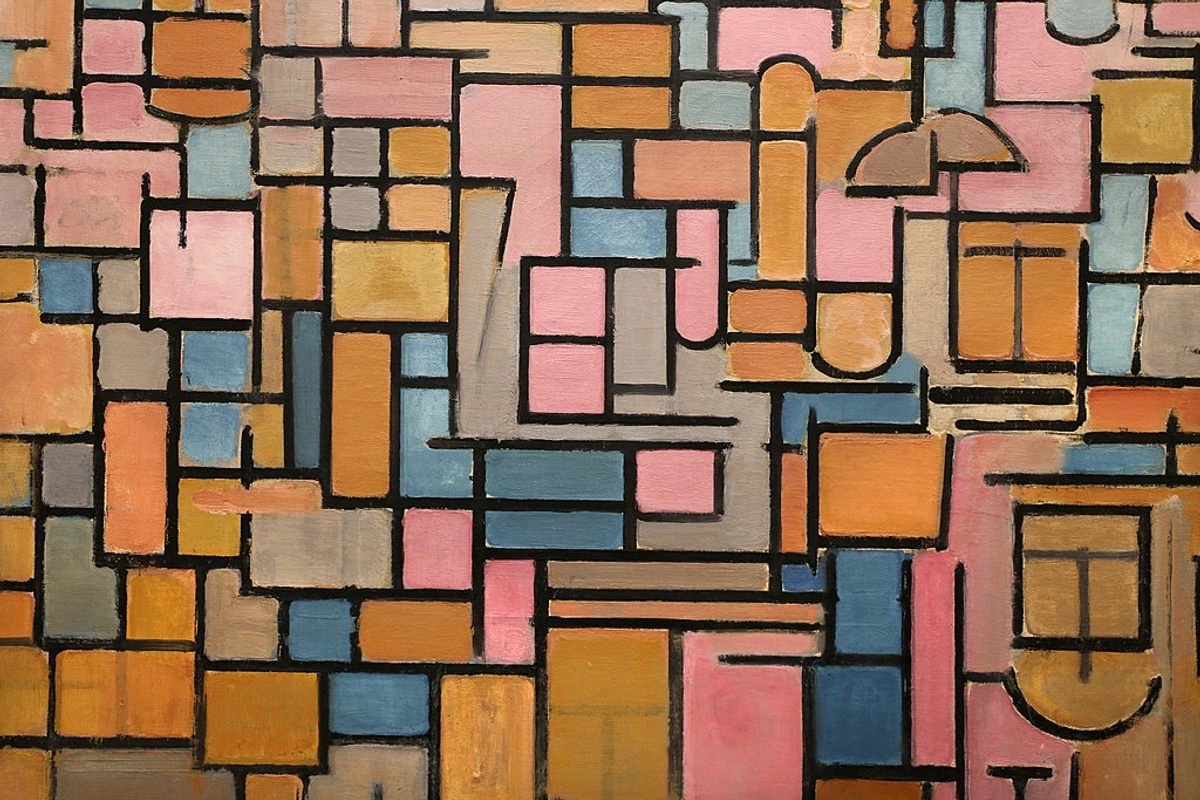

Think of Piet Mondrian and his iconic grids of primary colors. While distinct, his work shares Suprematism's commitment to basic geometric forms and a stripped-down palette, seeking universal harmony through abstraction. De Stijl, with its doctrine of Neo-Plasticism, aimed for a harmonious integration of art and life, emphasizing primary colors, black, white, and horizontal/vertical lines to achieve universal balance. They both sought a form of universal truth through abstraction, though Mondrian's universalism aimed for a balanced order within the world, distinct from Malevich's more spiritual, void-like purity. Malevich sought to transcend the material, while Mondrian aimed to find equilibrium within it, proving that even with shared foundational principles, the artistic journey can lead to vastly different, yet equally profound, destinations. It’s a similar feeling to finally getting a complex problem down to its simplest components; a real "aha!" moment that resonates across different artistic intentions.

The Bauhaus, with its revolutionary approach to art, craft, and design, also absorbed these principles. While not purely Suprematist, the emphasis on geometric forms, functionality, and a reductive aesthetic found fertile ground there, sometimes shifting the focus from spiritual transcendence to practical application, integrating these pure forms into daily life and industry. This marked a different, yet equally radical, evolution of abstraction. Artists like Wassily Kandinsky, with his theories on the spiritual in art and his exploration of form and color relationships, and Josef Albers, deeply exploring color interaction and the square as a fundamental module, found common ground with Malevich’s quest for essential forms and pure emotion, albeit through different avenues. László Moholy-Nagy, another key Bauhaus figure, extended these ideas into photography, sculpture, and graphic design, embracing light and transparency in a way that echoed Suprematism's dematerialization of form. The enduring legacy of this era is fascinating, and you can delve deeper into the Bauhaus movement's enduring influence and even explore Bauhaus artists' influence on art today.

Suprematism's Unseen Influence: Graphic Design, Architecture, and Beyond

From the integrated designs of the Bauhaus, Suprematism's influence extended even further, particularly into applied arts and the burgeoning field of graphic design and architecture. The movement's emphasis on clean lines, geometric forms, and bold, simplified compositions provided a visual language for a new, modern era, one that yearned for clarity amidst chaos. Think about the early 20th-century Russian avant-garde: artists like El Lissitzky took Malevich's non-objective principles and applied them to graphic design, typography, and architectural visions. His "Prouns" (projects for the affirmation of the new) were abstract, multi-dimensional compositions that served as a bridge between painting and architecture, almost like blueprints for a new, non-objective reality, demonstrating how Suprematist ideas could translate into concrete, functional designs that were both artistic and spatial. He created powerful propaganda posters, book designs, and even influenced urban planning, truly integrating art into everyday life. This push for a universal aesthetic based on fundamental forms became a cornerstone for movements like Constructivism and, as we've seen, the Bauhaus. It offered a crucial liberation, demonstrating how to abstract art not just technically, but conceptually.

This period, however, also saw the rise of a distinct, yet related, movement: Constructivism. While both embraced geometric abstraction, their core philosophies diverged significantly:

Feature | Suprematism | Constructivism |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Aim | To express "pure feeling" and spiritual experience; art for art's sake, detached from social function. | To serve the revolution and society; art should be utilitarian, functional, and applied to practical design, propaganda, and industrial production. |

| Focus | Non-objective, spiritual transcendence through fundamental geometric forms (squares, circles). | Materials, construction, engineering; applying abstract forms to real-world problems and creating "constructions" with an emphasis on texture and functionality. |

| Key Figures | Kazimir Malevich, Olga Rozanova, Ivan Klyun | Vladimir Tatlin, Alexander Rodchenko, El Lissitzky (though his "Prouns" bridged both worlds, he leaned into constructivist principles for applied work). |

| Perception | Often seen as cold or overly intellectual by some due to its spiritual abstraction. | Embraced for its practical application and alignment with socialist ideals, focusing on the material and the buildable. |

This table highlights a fascinating tension: the pursuit of pure, spiritual art versus art engaged with the world, a core philosophical divergence that continues to echo in contemporary debates about art's purpose.

The Post-War Abstraction Boom: Beyond Geometry?

After World War II, abstract art exploded in new directions. Abstract Expressionism, for instance, often moved away from the cool, hard edges of geometry towards gestural, emotional outpourings. It’s a bit like swapping a carefully constructed architectural blueprint for a raw, energetic dance. But even here, the foundational work of Suprematism was felt. The very idea that art could be purely non-representational, that it didn’t need a subject, had been firmly established. This radical proposition, initially perceived by some as cold or overly intellectual, provided the crucial permission for abstraction to exist as an autonomous language—a freedom Abstract Expressionists then exploded onto the canvas with gestural fervor, moving beyond geometric rigor into pure, subjective emotion. This allowed later artists to explore abstraction in myriad ways, from the intense drama of Abstract Expressionism to the cool, calculated surfaces of Minimalism.

Minimalism, in particular, owes a clear and undeniable debt to Suprematism's reductionist philosophy. Artists sought to remove all non-essential forms and ideas, focusing on pure shapes, colors, and materials. This wasn't just stylistic; it was a conceptual echo of Malevich's quest for "zero form," a desire to pare down to fundamental, irreducible elements. Minimalism took Suprematism's geometric purity and the concept of stripping down to essentials, and translated it into monumental, material experiences. It's a bit like tidying your workspace until only the absolute essentials remain; the focus sharpens, the message becomes clearer, echoing Malevich's quest for "zero form." The Ultimate Guide to Minimalism explores this fascinating movement in more depth.

My Brush with the Legacy: Suprematism in Contemporary Abstract Art

So, what does all this historical stuff mean for an artist like me, creating contemporary pieces today? Well, frankly, it’s the bedrock. Even when I’m throwing vibrant colors onto a canvas, creating what some might call "controlled chaos," the underlying principles of composition, the tension between shapes, the impact of color – it all owes something to those early pioneers. Sometimes, when I'm mapping out a new piece, I'll start with a simple square or rectangle in my mind, a foundational form that acts as a silent anchor, a nod to that initial impulse to strip everything away and build from pure geometry. It's a bit like admitting you still use training wheels, but these aren't for learning to balance; they're for remembering the core structure before the ride gets wild. This mental 'start point' allows me to then layer, scratch, and blend, confident that a core, almost spiritual, structure holds the piece together. In my studio, when I'm wrestling with a composition that feels too busy or unfocused, I often catch myself thinking, "What would Malevich strip away?" It’s a powerful mental exercise that helps me find the essential rhythm and balance, even in my most gestural works.

Artists like Gerhard Richter, with his stunning color grids and scraped abstract canvases, or Christopher Wool, known for his bold, often text-based, abstract paintings, aren't strictly Suprematists. Not at all. But their work, in its own way, carries forward the spirit of challenging perception, of exploring fundamental forms, repetition, and the raw impact of paint on canvas. Richter's systematic exploration of color in his grids, or his scraped "Abstract Paintings" which simultaneously reveal and obscure, echo Suprematism's concern with the pure visual experience and the limits of representation, almost like a scientific inquiry into the very building blocks of visual reality. Wool's stark, often stencil-based works, with their emphasis on line, form, and the texture of paint, distill visual language to its core, forcing a confrontation with the raw components of art. They make us look, really look, at what's in front of us, much like Malevich wanted us to. It’s about finding meaning in the seemingly meaningless, or rather, finding a different kind of meaning – a meaning rooted in pure visual experience, liberated from narrative. I've often felt this when I'm completely lost in a color study; it's just pigment, but it speaks volumes.

And then there's the work of Christopher Wool. His monumental, often text-based, paintings with their stark black and white forms feel like a direct lineage from Malevich's reductive philosophy. He simplifies, he repeats, he uses industrial techniques—all to strip away extraneous detail and force the viewer to engage with the raw power of line, form, and texture. His art, like Suprematism, demands that you confront the canvas on its own terms, finding beauty and complexity in its deliberate paring down. His repetition and industrial techniques, in their own way, channel Suprematism's desire for essential, impactful forms, albeit through a different, often urban, lens.

Why It Matters to Me (and Maybe You Too)

For me, the enduring impact of Suprematism lies in its fearless pursuit of purity and its belief in the spiritual power of abstract forms. It reminds me that sometimes, the simplest things hold the most profound truths. What is this "spiritual power"? It’s that feeling when a seemingly simple arrangement of shapes or colors resonates so deeply it transcends mere aesthetics, hitting you with a fundamental truth about balance, tension, or infinite space. Like when I placed a deep blue square against a vibrant red wash in a recent piece; it was just two colors, but their interaction created a palpable sense of both vastness and intimacy, a quiet hum that spoke volumes without a single recognizable image. I remember one afternoon, staring at a blank canvas, feeling overwhelmed by possibilities. Then I thought of Malevich's "Black Square" – a simple, powerful declaration. It wasn't about what to paint, but about what not to paint, about finding the essential. That moment often influences how I approach my canvas, how I think about color, and how I strive to create pieces that resonate on an emotional level, even without a recognizable subject. It's like a silent compass, always pointing me back to the core principles of visual impact. It’s the art of letting go, of stripping away the unnecessary, to reveal a truer, more potent message.

It encourages me – and hopefully, you – to look at abstract art not just as a pretty pattern or a splash of color, but as a deliberate, thoughtful exploration of form, emotion, and the very nature of seeing. If you've ever found yourself wondering how to find meaning in abstract works, this historical context can be a wonderful guide to demystifying abstract art and understanding what makes abstract art compelling. Maybe it'll even inspire you to check out some of my art for sale and see if you can feel the echoes of these grand ideas in my own work.

Frequently Asked Questions about Suprematism's Influence

What is Suprematism in simple terms?

Suprematism was an early 20th-century Russian art movement founded by Kazimir Malevich. It focused on basic geometric forms (like squares and circles) and a limited color palette to create "non-objective art." Its goal was to express "pure feeling" and spiritual experience, freeing art from depicting real-world objects or narratives.

What are the key visual characteristics of Suprematist art?

Suprematist art is primarily characterized by its use of fundamental geometric forms such as squares, circles, rectangles, and crosses. These shapes are often arranged dynamically and asynchronously on a white or light-colored background, creating a sense of floating or movement. The color palette is typically restricted to primary colors (red, blue, yellow), black, and white, emphasizing purity and the absence of decorative elements.

Who was the founder of Suprematism?

Kazimir Malevich was the founder of Suprematism, famously exhibiting his iconic "Black Square" in 1915 as a radical symbol of the movement's principles. While he was the central figure, other artists like El Lissitzky also contributed significantly to its development and spread.

How did Suprematism influence modern design?

Suprematism's emphasis on geometric abstraction, pure form, and functional simplicity heavily influenced modern design, particularly movements like De Stijl, Constructivism, and the Bauhaus. Its principles found applications not only in fine art but also in graphic design, typography, architecture, and industrial design, promoting the idea that art and design could be integrated and that basic forms had universal aesthetic appeal.

How did the political context of early 20th-century Russia influence Suprematism?

The tumultuous political and social landscape of early 20th-century Russia, marked by revolution and radical change, profoundly influenced Suprematism. Malevich and his followers saw the destruction of old systems as an opportunity to create a new, pure art form free from the ideological baggage of the past. While not explicitly political in its aesthetic (unlike Constructivism, which aimed for direct social utility), its radical break from tradition and embrace of a 'new art for a new world' inherently aligned with the revolutionary zeal of the era, reflecting a broader societal yearning for a fresh start and a utopian future, free from the old constraints.

Is Suprematism still relevant today?

Absolutely. While a historical movement, its core ideas about non-representation, geometric purity, and the spiritual power of abstract forms continue to influence contemporary abstract artists, architects, and designers, shaping how we perceive and create abstract art. It’s a quiet but persistent undercurrent in the broader ocean of modern aesthetics.

Conclusion: The Unseen Threads

So, the next time you encounter an abstract painting, whether it's a bold geometric composition or a riot of expressive color, take a moment. Pause. You might just feel the quiet hum of Suprematism's legacy, a subtle reminder of the brave souls who first dared to paint beyond the visible world. It's a reminder that truly groundbreaking ideas, even if initially met with a shrug, ripple through time, forever changing the landscape of how we see, how we create, and how we connect. My own path, for instance, was irrevocably altered the day I finally 'saw' the Black Square not as an absence, but as a beginning – a profound moment that continues to inform every stroke, every color choice, in my studio. Suprematism, for all its starkness, has woven itself into the very fabric of how we understand abstract expression, constantly challenging us to look beyond the obvious and find meaning in the pure, autonomous language of art. To see how these influences have shaped my own artistic journey, you can explore my timeline, or if you're ever in the mood to connect with art in person, consider visiting my museum in 's-Hertogenbosch.