Russian Constructivism: Art's Blueprint for a New World & My Abstract Echoes

Discover Russian Constructivism's radical utility, geometric precision, and profound influence on modern design, and how its revolutionary spirit shapes my contemporary abstract art.

Russian Constructivism: A Revolutionary Blueprint for Art, Life, and My Abstract Work

There are moments when an artistic discovery isn't just a flicker of awareness, but a profound, almost visceral recognition—a quiet, persistent hum—a 'Wait, I've felt that aesthetic before... that precise structural impulse.' It's like finding a long-lost artistic relative whose DNA is subtly woven into your own creative fabric, and frankly, into the very visual language of the world around us. That's exactly the sensation I get with Russian Constructivism: its powerful, often unseen echoes resonate not just in my contemporary abstract art, but across much of the modern design landscape, even if we rarely consciously acknowledge its profound legacy. And honestly, it feels like this movement, in its radical approach, offered a blueprint for art to be more than just pretty pictures – it envisioned art as an active participant in shaping life itself.

We tend to get swept up in the immediate, the fleeting trends of the 'now.' But the past, oh, the past is less a bygone era and more a deep, persistent current, subtly shaping our present trajectories and nudging us towards unexpected futures. Few movements have laid down such an indelible, structural blueprint on modern art and design as the revolutionary, pragmatic spirit of Russian Constructivism.

This is more than just history; it’s a living dialogue. It’s about how an ideological firestorm from a century ago can still ignite something profound in a contemporary studio, connecting my brushstrokes to a grander narrative of art's purpose. To truly understand this resonance, we must first delve into the origins of this powerful movement that sought to fuse art with engineering, architecture, and social progress. So, come with me, let's pull back the curtain on this powerhouse.

What Was Russian Constructivism? Art as a Tool for a New World

Let's set the scene: Russia, roughly 1915 to the early 1930s. The October Revolution had just reshaped a nation, and a generation of artists and designers were buzzing with an almost utopian zeal—a fervent belief that art could genuinely transform society. They didn't just want to create beautiful objects; they envisioned a society built on rational organization, technological advancement, and collective good. Art, for them, wasn't merely a reflection of this new world, but a direct means to construct it, impacting every facet of daily life from city planning to the clothes people wore.

They looked at traditional, 'bourgeois' art—the pretty pictures, the gilded frames, the 'art for art's sake' philosophy—and declared it irrelevant. What did 'art for art's sake' mean to them? It was a relic of the old world, exemplified by academic painting or Symbolist works focused on individual emotion or aesthetic pleasure for an elite few, detached from social function. The Constructivists' mantra, in stark contrast, was that art wasn't about detached contemplation or beauty for beauty's sake; it was about utility, about building a new world, literally and figuratively. This wasn't just an art style; it was a radical philosophy, a pragmatic attempt to fuse art with engineering, architecture, and social progress. It was a call for art to be a method, a means to an end, a tangible force for change, rather than an end in itself. This philosophy even led to the development of Productivism, where artists directly applied their skills to industrial production, designing everything from factory tools to everyday consumer goods, ensuring art served the masses in the most practical sense.

They envisioned art as a tool for the revolution, actively participating in the construction of a new society. This meant art was everywhere: from powerful agitprop (agitation propaganda) posters designed to stir public opinion and solidify revolutionary ideals, to functional public installations, utilitarian furniture, innovative theatre sets, and even clothing design. The core idea was to strip away embellishment and focus on objective elements: lines, planes, and volumes. This emphasis on industrial materials like metal, glass, and wood, combined with a stark, efficient aesthetic, gave birth to the 'machine aesthetic' – a celebration of modern engineering, mass production, and the visual language of the factory floor. Their work often mimicked the precision and functionality of machinery, reflecting a belief in progress and a rejection of ornamental excess.

Key figures emerged from this fertile ground, each pushing the boundaries of what art could be:

Artist | Primary Contribution | Defining Characteristic |

|---|---|---|

| Vladimir Tatlin | Monumental Architectural Projects | "Monument to the Third International" – art serving society; early pioneer of industrial materials |

| Alexander Rodchenko | Photography, Graphic Design, Painting | Bold typography, geometric forms, iconic posters; photomontage |

| El Lissitzky | Architecture, Design, Photography, Typography | Developed "Proun" – "projects for the affirmation of the new," bridging painting and architecture through abstract, dynamic compositions |

| Lyubov Popova | Dynamic Abstract Painting, Theatrical Sets | Industrial elements, primary colors, energetic compositions; textile design |

| Varvara Stepanova | Textile/Clothing Design, Stage Sets, Graphic Art | Functional geometric patterns for mass production; pioneering sports clothing designs |

These pioneers sought to impose order and structure on a chaotic world, creating a 'dynamic purpose' where art served the masses. As someone whose studio often feels like a beautiful, controlled chaos, where I wrestle with lines and forms to find a balanced tension, I can certainly appreciate their desire for rigorous structure, even if my own approach is sometimes a playful rebellion against it.

![]()

This fascinating chapter in art history, which I explore further in the ultimate guide to abstract art movements, showcases how deeply design in art can be intertwined with societal change. If you're curious about the broader spectrum of how art evolves, delving into the evolution of abstract art offers even more context, including the less structured, more emotional counterpoints found in other movements.

By the early 1930s, however, the utopian dream began to fade. The Soviet state, under Stalin, increasingly favored Socialist Realism, a doctrine promoting easily digestible, figurative art glorifying the worker and the party. This shift wasn't merely ideological; Constructivism's abstract 'formalism' was deemed too complex, too elitist, and not easily understood by the masses, despite the artists' original intentions. It simply didn't serve the new political narrative as directly as state-sanctioned propaganda. While some Constructivists, like Rodchenko, attempted to adapt their work or pivoted to photography and industrial design, many were suppressed, forced to abandon their styles, or even silenced. This suppression was also fueled by internal debates within the movement itself, where ideological purity was sometimes prioritized over artistic freedom, making it vulnerable to external control. It was a heartbreaking end to such a vibrant, experimental period, a stark reminder of art's vulnerability to political shifts. Yet, their ideas, like seeds carried by the wind, had already spread far beyond Russia's borders.

Enduring Influence: How Constructivism Shaped Modernism

Despite its suppression in Russia, Constructivism's principles proved remarkably resilient and influential globally. They profoundly impacted movements like the revolutionary Bauhaus movement in Germany and De Stijl in the Netherlands. At Bauhaus, the emphasis on functional design, industrial materials, and a stark, geometric aesthetic found a fertile new home in architecture, furniture, and graphic design, directly echoing Constructivism's call for art to be integrated into daily life. For instance, the furniture designs of Marcel Breuer or the graphic work of László Moholy-Nagy at the Bauhaus clearly reflect the Constructivist embrace of industrial materials and geometric forms. Similarly, De Stijl's pure geometric forms, primary colors, and grid-based compositions directly reflected the Constructivist pursuit of universal order and clarity. Think of Gerrit Rietveld's "Red and Blue Chair," an iconic piece of De Stijl design that champions simplified, structural elements and primary colors, much like a Constructivist artwork. It’s a powerful reminder that truly revolutionary ideas, even when stifled at home, find ways to echo globally and shape the future in unexpected ways. You can suppress an art movement, but you can’t fully extinguish an idea.

The Constructivist Ghost in My Studio: A Personal Dialogue with Structure

No, I’m not sketching propaganda posters or designing revolutionary theatre sets (though, if my cats ever stage a coup, I’ll be ready, equipped with tiny, geometrically perfect helmets and a clear manifesto). But the fundamental tenets of Constructivism—its unwavering emphasis on compositional rigor, its enduring affection for pure geometry, and its conviction that art serves as a structured language—these echoes are undeniably woven into the abstract work I create. And, honestly, they’re humming beneath the surface of much contemporary art, too, often without artists even realizing the lineage. It’s a beautiful, subconscious inheritance, a silent conversation with artists long past that shapes what we create today. It’s a dialogue I often find myself having, even when I'm just wrestling with a blank canvas, wondering how to give form to an unformed idea.

Geometry as a Language, Not a Constraint: Embracing Controlled Chaos

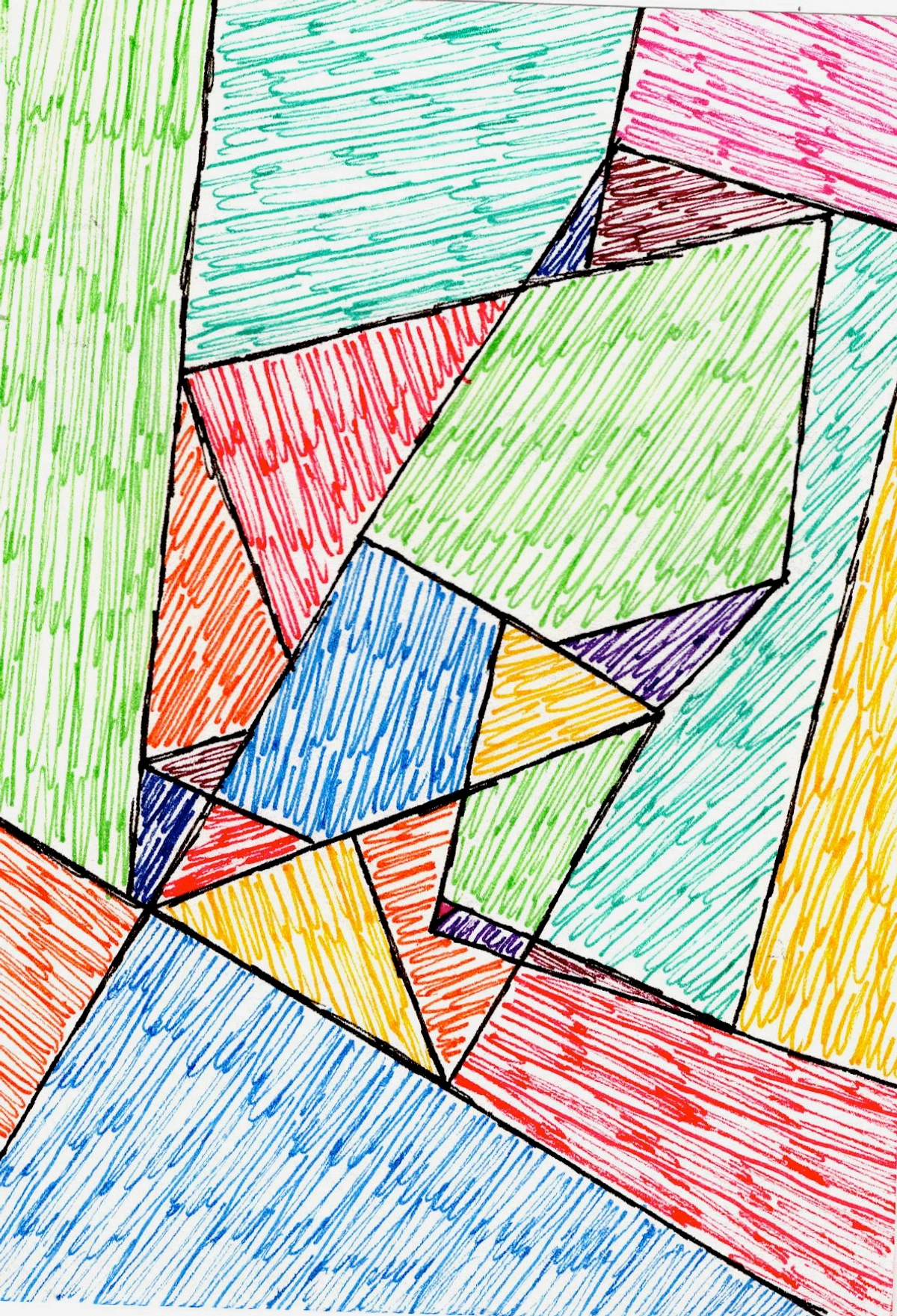

There’s a beautiful tension I chase when I work, a delicate dance between instinct and intention. Sometimes, when layering colors or building a new piece, my hand almost instinctively reaches for those strong, foundational geometric shapes. A decisive rectangle anchors a swirling vortex of color; an intersecting line cuts through perceived chaos. I think of it like this: imagine a canvas alive with fluid, expressive marks – a riot of vibrant teal, orange, and gold. Then, a single, stark black line bisects it, not as a decoration, but as an architectural beam. It's a structural element that defines space, creates tension, and guides the eye, much like a Constructivist architect might structure a building to direct movement. I remember one time, a canvas felt overwhelmingly busy, a beautiful but chaotic explosion of color. I almost gave up, but then, almost on a whim, I painted a bold, off-center black square. Suddenly, the chaos had a container, a focal point, a new, exhilarating dynamic. It was a clear echo of that Constructivist desire to impose order.

Or, in a piece like my own Geometric Embrace, you can see how a series of intersecting lines creates a dynamic scaffold, within which softer, more organic shapes find their place and energy. This isn't about slavishly recreating a historical blueprint; it's about harnessing these pure forms as essential building blocks, imbuing the otherwise free-flowing or expressive elements with a vital sense of stability, dynamic tension, or what I often think of as 'controlled chaos.' It’s the satisfying feeling of imposing a clear framework while allowing for spontaneous bursts of energy, like a well-choreographed dance between order and intuition. It's where the unexpected happens within a defined space, much like a jazz improvisation built on a solid chord progression.

This approach is a powerful tool for understanding how composition guides my abstract art and adds deeper meaning, allowing me to explore the symbolism of geometric shapes without uttering a single word. Even when I’m just lost in the art of mark-making, those underlying structural whispers often find their way to the surface. It’s a constant reminder that even the most spontaneous gesture benefits from a hidden backbone, a quiet nod to its Constructivist ancestors.

The Power of Purpose and Play: Beyond the Canvas

The Constructivists, in their relentless pursuit of directness and visual power, often restricted their palettes to primary colors: red, black, and white. It was about immediate, undeniable impact, a visual punch aimed at provoking political action and revolutionary fervor. Now, while my current obsession with vibrant teal might make a few old Constructivists (gently) raise an eyebrow in their geometrically perfect graves—perhaps muttering about "bourgeois chromatic indulgences"—I still find immense power in strong, contrasting hues and bold statements. It’s about impact, about forcing the viewer to stop, to engage, to feel something visceral. Where they aimed to provoke political action with stark visual messaging, I aim to provoke an emotional or sensory response—a moment of pause, a shift in mood, an invigorating jolt of color that cuts through the everyday visual noise.

This shared philosophy of using color for potent effect is a direct echo, a recognition that color isn't just decoration but a powerful tool for communication. You can learn more about how artists use color and the psychology of color in abstract art in other articles on the site, but for me, it's about harnessing that Constructivist directness for a different, more personal kind of 'revolution' in perception.

Where the Constructivists sought to literally integrate art into everyday life through architecture and industrial design, my contemporary take is perhaps more about emotional and experiential integration. My goal isn’t merely to create a visually pleasing image, but to craft a visual experience that captures your attention, encourages a moment of pause, or subtly transforms the mood and energy of your space. For example, a piece with bold, upward-sweeping diagonals might energize a workspace, while a balanced composition of soft, interlocking forms could bring a sense of calm to a living room. This concept of art as an active, functional presence is something you can tangibly experience if you ever find yourself near my little museum in 's-Hertogenbosch, where these principles play out in the physical layout and collection itself. It's a living exhibition of how structured thought can lead to emotive, dynamic expression, and perhaps even inspire you to explore a piece for your own space. This personal engagement with foundational art theories is what makes my artist's journey a continuous exploration.

Spotting the Echoes: A Guide for the Curious Eye in Your World

So, next time you're contemplating a piece of contemporary abstract art—or even just scrolling through design feeds, scanning a modern brand logo, or interacting with a sleek user interface—how can you pick out these subtle (or, at times, gloriously overt) Constructivist echoes? It's a fun exercise, a way to connect with the historical currents shaping the present, even as you learn how to abstract art yourself. From minimalist interiors to bold brand logos and efficient app designs, the Constructivist aesthetic is surprisingly ubiquitous once you know what to look for. Beyond the obvious graphic design, think about the functional elegance of an Eames chair, the streamlined form of a modern appliance, or the clear, hierarchical structure of a well-designed infographic – all whisper echoes of Constructivism’s influence.

Look for:

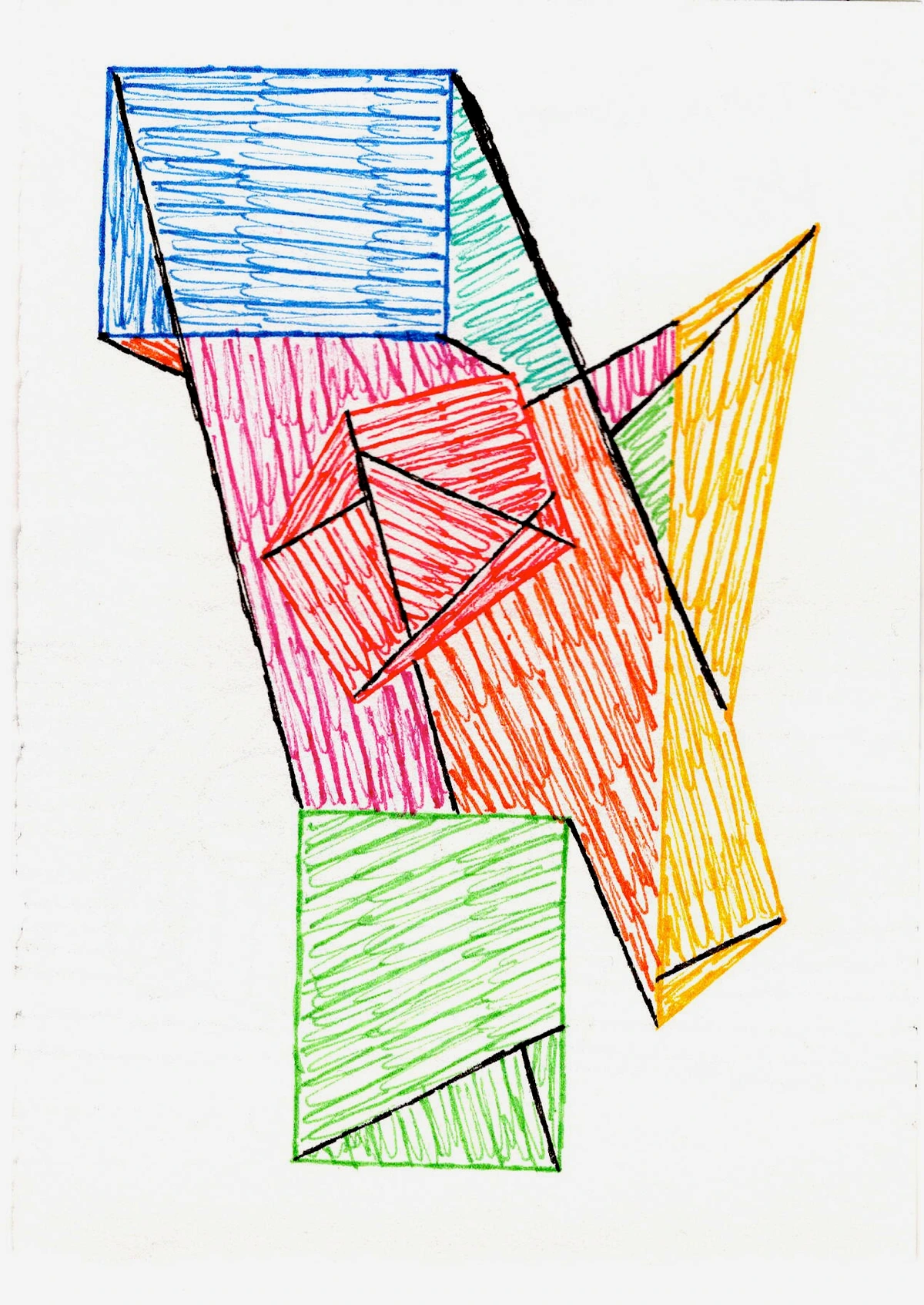

- Bold Geometric Forms: Think sharp angles, assertive squares, precise circles, and powerful lines that aren't just decorative but serve as fundamental compositional elements. They create a compelling sense of order or invigorate dynamic tension, much like the structural beams of a modern building or the clear-cut shapes of an iconic logo.

- Limited, High-Contrast Color Palettes: While perhaps not strictly the Constructivist red, black, and white, seek out compositions that leverage strong contrasts—often primary or secondary colors against neutrals—to create undeniable visual impact and clarity. Think of many modern corporate logos or posters that achieve maximum impact with minimal color.

- Dynamic Compositions & Asymmetry: A powerful sense of movement, tension, or energy created through the deliberate arrangement of elements. Look for asymmetric balances and prominent diagonals that push and pull the eye, reflecting a "machine aesthetic" or a sense of purposeful direction. This often manifests in layouts that feel energetic and unbalanced in a deliberate way, guiding your gaze.

- Industrial Aesthetic & Rawness: Sometimes, this manifests as an embrace of raw, unrefined materials, simplified forms, or a certain starkness that hints at efficiency, function, and a rejection of the purely decorative. Think visible textures, metallic sheens, or compositions that evoke architectural blueprints, or the unadorned functionality of modern industrial design, like exposed concrete or steel elements.

- Revolutionary Typography: Consider how text is used. Constructivists revolutionized typography with bold, sans-serif fonts, dynamic layouts, and the integration of text and image as a cohesive visual message, influencing modern graphic design profoundly. The impactful, functional use of type is a direct legacy.

![]()

It’s important to remember that not all abstract art bears the mark of Constructivism. The movement was suppressed in its homeland by the 1930s as Stalinist ideology favored Socialist Realism, but its ideas spread globally, cross-pollinating with other avant-garde movements and even influencing early American modernism in certain aspects. Its legacy is a testament to the power of art to be more than just pretty – to be purposeful, revolutionary, and enduring. It's the silent language underpinning so much of the visual world we navigate today.

The Unseen Threads of History: A Continuous Dialogue

For me, acknowledging these deep historical roots isn't just an academic exercise; it profoundly enriches my own creative journey. It’s a comforting thought, realizing that the struggles, the utopian visions, and the breakthroughs of artists a century ago still resonate through my brushstrokes and your perception today. It reminds me that art is a continuous dialogue, a conversation across time and cultures, a constant ebb and flow of influence. Perhaps, the next time you encounter abstract art, you’ll not just see shapes and colors, but truly feel those unseen echoes too, connecting you to that powerful, revolutionary spirit that sought to rebuild the world through art. And who knows, maybe that connection will inspire you to explore a piece for your own space, carrying a little bit of that dynamic history with you, transforming your environment with its structured energy and vibrant purpose. It's more than just a painting; it's a piece of that continuous, echoing conversation, a tangible link to a past that still shapes our present. What a profound legacy for a movement that, against all odds, chose to build a new world through art.