The Definitive Guide to Renaissance Art: A Personal Journey Through Humanity's Awakening

Art history, for me, has always felt like a sprawling family saga, complete with larger-than-life characters, dramatic turns, and those rare, truly groundbreaking moments that shift everything forever. If art history is a saga, the Renaissance is undeniably that epic middle chapter where things suddenly get really interesting. For a long time, the word 'Renaissance' brought to mind dusty textbooks and those solemn, almost stiff figures in frescoes – all a bit flat and unapproachable, bathed in an almost oppressive golden glow. Not exactly my usual cup of tea, given my penchant for the vibrant chaos of contemporary colorful art. But then, you actually look at it, properly, and you realize it's anything but dusty. It's a period of explosive creativity, profound thought, and a sudden, exhilarating embrace of humanity. It's when art, while still devotional, broadened its gaze, becoming deeply centered on us.

This guide isn't just a historical overview; it's a deep dive into what truly ignited this explosion of creativity. We'll explore the philosophical shifts, the groundbreaking techniques, the titans who shaped it, and how it all still resonates today, captivating my own artistic journey. We'll trace its origins, uncover its driving forces, marvel at its brilliance, meet the masters, and finally, reflect on its enduring impact on us, both then and now, culminating in how this echoes in my contemporary approach to art, influencing my composition and expression. Prepare to journey from medieval shadows to Renaissance light, discovering the profound human quest that still speaks volumes. If you're looking for a comprehensive overview of this era, our ultimate guide to Renaissance art is a great starting point for understanding this pivotal moment in art history.

What Even Is Renaissance Art? (And Why It Still Captivates Me)

At its heart, the Renaissance (meaning "rebirth" in French – a term coined much later, mind you) was a sweeping cultural movement that largely originated in Italy, particularly Florence, during the 14th to 17th centuries, before spreading across Europe. It wasn't merely a stylistic change; it represented a fundamental shift from the predominantly symbolic, spiritual, and often flattened forms of the Gothic era, where art largely served the church, towards a fervent celebration of human experience, naturalism, and classical ideals. Think of the soaring, ethereal Gothic cathedrals versus the balanced, earthly, and human-scaled architecture emerging in Florence. It was Europe collectively shaking off a long nap, stretching, and then exclaiming, "Wait, we can do that?!"

This profound shift, a conscious revival of classical Greek and Roman ideas in art, literature, philosophy, and science, followed what was often (and perhaps unfairly) seen as the "dark" Middle Ages. Suddenly, people were looking at the world with fresh eyes, asking big questions, and realizing that perhaps, human potential was limitless. This rediscovery spurred not only artistic innovation but also advancements in politics, education, and various scientific fields, laying groundwork for the modern world. While Italy, particularly Florence and Rome, became its vibrant epicenter, the Renaissance was a continent-wide phenomenon, manifesting in distinct ways across Northern Europe, and even seeing more limited engagement or later adoption in regions like Spain and England. Crucially, the prosperity of growing city-states, fueled by a burgeoning merchant class and expanding trade routes, provided the necessary wealth and environment for this cultural explosion, transforming towns into vibrant hubs of intellectual and artistic exchange. For a deeper look into its Italian roots, explore our ultimate guide to Renaissance art in Italy.

What truly made this era so groundbreaking, and how did it set the stage for everything that followed?

Echoes from the Past: From Medieval Shadows to Renaissance Light

The notion of the "dark" Middle Ages is, of course, a simplification. While often marked by a decline in classical learning and societal upheavals that made intellectual and artistic innovation challenging, it was also a period of deep religious devotion, significant cathedral building (with the astonishing feats of Gothic engineering), the rise of scholasticism (where classical texts were preserved and studied in monasteries and early universities), and the establishment of early universities themselves. Even within this period, seeds of change were sown, paving the way for the brilliant conflagration of the Renaissance. The cataclysmic Black Death in the mid-14th century, while devastating, paradoxically led to societal restructuring and a re-evaluation of life, death, and human experience. With massive depopulation, labor became more valuable, feudal structures weakened, and there was an increased focus on individual piety and a direct connection with the divine, fostering a shift from communal suffering to individual experience. This opened up new avenues for artistic patronage beyond the church to wealthy individuals and emerging merchant classes, creating a more diverse and competitive market for art, including private portraits and elaborate domestic commissions.

Early artistic innovations began to challenge the prevailing Byzantine styles. Artists like Cimabue and Duccio in the 13th and early 14th centuries began to infuse their work with greater human emotion and naturalism. However, it was figures like Giotto (c. 1266/7 - 1337), who truly broke ground, moving away from flat, symbolic forms towards depicting figures with volume, weight, and emotional depth in his frescoes. Following Giotto's innovations, Early Renaissance masters such as Masaccio (known for his revolutionary use of linear perspective and realism in works like The Holy Trinity), Donatello (who revived classical sculpture with unprecedented naturalism and emotional intensity in his David), and Botticelli (whose lyrical lines and mythological themes like The Birth of Venus defined a distinct Florentine aesthetic) further cemented these foundational shifts. Their innovations in perspective, anatomy, and narrative storytelling laid crucial groundwork, making the Florentine Renaissance not a sudden spark, but a brilliant conflagration fueled by earlier embers. It’s a bit like watching a tiny stream grow into a roaring river – the momentum was building for centuries.

The Engine of Rebirth: Patrons, Philosophers, and Progress

So, if the seeds were sown and the ground prepared, what truly fueled this artistic explosion in Italy? The Renaissance didn't just happen; it was cultivated, funded, and championed by a society hungry for new ideas, new ways of seeing, and new expressions of humanity. It's a testament to the era's unique blend of ambition, intellect, and sheer financial muscle, proving that even the greatest genius needs a stage, resources, and an appreciative audience.

Humanism's Embrace: The Focus on Us

The philosophical backbone of the Renaissance was Humanism. It wasn't about abandoning faith, but about a renewed emphasis on human potential, achievements, and capabilities. Scholars rediscovered and translated classical Greek and Roman texts, leading to a profound shift from a purely God-centered worldview to one that balanced divine reverence with admiration for human intellect and earthly experience. This meant an explosion in education, rhetoric, and a civic-minded approach to society.

Central to this was the concept of virtù, an ideal of excellence encompassing skill, talent, and moral fortitude, urging individuals to strive for their highest potential – a perfect mirror for the ambitious artists of the era. This vision also gave rise to the ideal of the "uomo universale" or "Renaissance Man," a polymath proficient in many fields, epitomized by figures like Leonardo da Vinci and Leon Battista Alberti, who excelled in architecture, painting, poetry, and philosophy. The advent of the printing press in the mid-15th century was revolutionary here, allowing classical texts and humanist treatises to be disseminated far more widely and rapidly, fueling intellectual curiosity across Europe. This also fostered civic humanism, a belief that individuals had a responsibility to contribute to the well-being and beauty of their community, which greatly influenced the commissioning of public art and architecture that adorned city squares and cathedrals, such as the competition for the Florence Baptistery doors or the construction of the Duomo. Artists, inspired by this ethos, sought to depict the human form with dignity, grace, and psychological depth, making figures relatable, not just symbolic. It’s a powerful reminder that curiosity about ourselves can be just as profound as curiosity about the cosmos – sometimes I think my abstract pieces are just me, trying to understand myself through color, without all the historical fuss.

The Power of Patronage: Art's Indispensable Sponsors

Behind every masterpiece often stood a powerful patron. Families like the Medici of Florence, the Sforza of Milan, and the Gonzaga of Mantua poured immense wealth into commissioning art, architecture, and scholarship. The Papacy in Rome became another colossal patron, transforming the city into a new center of artistic innovation. Beyond these powerful families and the Papacy, influential merchant families and bankers also played a significant role, often commissioning lavish private chapels, portraits, and domestic art that further spurred artistic output. Importantly, Guilds (associations of craftsmen, like the Wool Merchants' Guild in Florence which sponsored the Baptistery doors) and various civic bodies also played a significant role, commissioning public works that adorned city squares and cathedrals, making art a collective civic pride, not just a private luxury. Even powerful religious orders and individual monasteries commissioned works, serving as centers of learning and artistic production. We must also acknowledge the crucial, though often overlooked, contributions of powerful female patrons like Isabella d'Este, Marchioness of Mantua, who actively sought out and supported leading artists and writers, shaping the artistic landscape through her discerning commissions, often for her elaborate studiolo. These patrons were driven not just by a desire for display, but also by genuine intellectual curiosity, spiritual devotion, and a deep-seated civic pride that sought to beautify their cities and leave a lasting legacy. This system allowed artists to dedicate themselves fully to their craft, providing financial security and access to materials, pushing boundaries and creating works of unparalleled scale and ambition.

Workshops, Guilds, and the Artist's Evolving Role

Before the Renaissance, artists were often seen primarily as skilled craftsmen, typically organized into guilds that controlled training, production, and commerce. Their work was often collaborative and anonymous, focused on utility and religious instruction rather than individual expression. The Renaissance saw a gradual elevation of the artist's status from artisan to intellectual and even celebrity. Workshops, like those of Verrocchio (where Leonardo trained) or Ghirlandaio (where Michelangelo apprenticed), were bustling hubs of learning and production. Masters taught apprentices drawing, painting, fresco techniques, and sculpture, passing down invaluable knowledge. As artists like Leonardo and Michelangelo gained renown, their individual genius was celebrated, paving the way for the modern concept of the artist as a singular creative force, a far cry from the anonymity of many medieval creators. This shift also influenced how art was viewed, moving from a craft to a liberal art, worthy of intellectual study. What other groundbreaking shifts truly defined this era, visually and intellectually?

The Visual Language of Genius: Hallmarks of Renaissance Brilliance

So, the intellectual currents and financial backing were there. What did it look like when all those forces converged? What exactly makes these paintings so captivating, so utterly different from what came before? It's not just the fancy clothes or the religious subjects. It's the underlying philosophy and the groundbreaking techniques, often informed by a surge in scientific understanding. Here's what really grabs me, sometimes making me wonder how they managed it all:

Perspective and Depth: Creating Illusionary Worlds

Before the Renaissance, paintings often looked flat, almost like cut-outs. Suddenly, artists and architects like Brunelleschi and Masaccio started playing with linear perspective. They figured out how to create the illusion of three-dimensional space on a two-dimensional surface, with a vanishing point. It's mind-blowing how they created the illusion of depth, pulling the viewer directly into the imagined world of the painting. It makes you feel like you could step right into the canvas. I still remember the frustration of trying to draw a convincing cube in art class without it looking like it was melting or floating; their mastery of geometry, optics, and mathematics truly impresses me. This technique dramatically enhanced realism and narrative impact. If you want to delve deeper into this fascinating technique, explore our definitive guide to understanding perspective in art.

Humanism and Realism: Capturing the Soul

This is where it gets really personal for me. The Renaissance celebrated humanism, shifting focus from the purely divine to the human experience. Inspired by rediscovered classical texts and philosophical movements like Neoplatonism, artists began to portray figures with newfound realism and emotional depth. They studied anatomy as a scientific discipline, meticulously exploring musculature, skeletal structures, and emotion. This often involved direct observation and even cadaver dissection, giving them an unparalleled understanding of the human body and its movements. Figures in paintings weren't just symbols; they were people with feelings, caught in moments of drama, joy, or sorrow. You see a raw, honest portrayal of the human body and spirit that hadn't been seen since antiquity. It's a powerful reminder that art, at its best, explores what it means to be alive, and even when understanding symbolism in Renaissance art, the human element shines through. I sometimes wonder if my abstract pieces, in their own chaotic way, are still trying to dissect and understand the human experience, just without the need for an actual cadaver – thankfully.

Classical Revival: Reinterpreting Ancient Wisdom

Renaissance artists devoured ancient Greek and Roman art and philosophy. They rediscovered classical proportions, mythological themes (drawing inspiration from works like Ovid's Metamorphoses), and the sheer beauty of the human form. This revival was also deeply informed by Roman architectural and engineering principles, such as the grand scale and structural innovations seen in ancient Roman buildings like the Pantheon, and the writings of Vitruvius on ideal proportions. The study of ancient sculpture, like the recently rediscovered Laocoön Group, also provided crucial models for idealized forms. The rediscovery and translation of texts by philosophers like Plato and orators like Cicero also fueled this intellectual and artistic movement. But they didn't just copy; they interpreted. They took the wisdom of the ancients and infused it with their own unique spirit, creating something entirely new and vibrant. It's like taking a beloved old recipe and adding your own secret ingredient – familiar, yet delightfully fresh. This renewed interest in depicting realistic form and volume also paved the way for new explorations of light and shadow.

Light, Shadow, and Emotion: Chiaroscuro & Sfumato

This is a technique that still fascinates me today. Chiaroscuro, the use of strong contrasts between light and dark, usually bold contrasts affecting a whole composition, was perfected during this period. It creates dramatic tension, sculpts forms, and directs the viewer's eye. Think of the intense shadows and highlights that make a figure pop out of the canvas – it's pure magic, pulling you into the narrative and making you feel the emotion almost physically. It’s the kind of thing that makes you want to reach out and touch the canvas, just to make sure it’s really flat.

Another related technique, often employed by Leonardo, was Sfumato, a soft, hazy blurring of lines and colors, creating a subtle transition between tones and an almost ethereal atmosphere. When you look at the Mona Lisa's smile, for instance, that elusive, gentle quality is sfumato at work. It lets forms emerge subtly from shadow, rather than being sharply defined, creating an almost ethereal atmosphere and adding an air of mystery and depth that makes you feel like you can never quite grasp it, just like some fleeting thoughts in my own studio when I’m trying to make two colors blend just so.

The Power of Oil: Richness and Detail

While tempera and fresco were dominant, the Renaissance saw the increasing use and mastery of oil painting. This technique, pioneered by artists in the North (like Jan van Eyck), had its advantages quickly recognized and adapted by Italian masters. Artists like Antonello da Messina were crucial in introducing and disseminating oil painting techniques in Italy, leading to distinct regional developments and innovations in the medium. This medium allowed for richer, deeper colors, smoother transitions between tones, and an unprecedented level of detail and luminosity. Its slow drying time allowed artists to blend colors seamlessly, build up transparent glazes, and capture subtle textures and atmospheric effects that define so much of the era's masterpieces. It transformed what was possible on canvas. If you're curious about the technical aspects, our definitive guide to oil painting techniques offers a deeper dive.

Renaissance Architecture: Temples of Humanism

Beyond painting and sculpture, architecture underwent a profound transformation, becoming a core expression of Renaissance ideals. Architects like Filippo Brunelleschi (with his groundbreaking dome of the Florence Cathedral) and Leon Battista Alberti (whose De re aedificatoria codified classical architectural principles) sought to revive the harmony, symmetry, and classical orders of ancient Rome and Greece. This meant a return to geometric forms, clear proportions, and a human scale, often incorporating elements like columns, pilasters, round arches, and coffered ceilings. These structures were not just functional; they were seen as rational, beautiful, and reflective of the human intellect, embodying a spiritual beauty through mathematical perfection. Think of the calm balance of Brunelleschi's Pazzi Chapel or Alberti's Santa Maria Novella facade – they feel profoundly different from the towering, often asymmetrical Gothic cathedrals that preceded them. It's a reminder that beauty often lies in elegant solutions, a lesson I often ponder when simplifying complex forms in my own abstract work. I still get a headache thinking about the math involved in some of those domes; good thing my art is less about perfect circles and more about glorious chaos.

Scientific Underpinnings: Art Meets Inquiry

The Renaissance wasn't just about aesthetic innovation; it was deeply intertwined with scientific inquiry. Artists were often scientists, or at least keenly observed the world with a scientific eye. Their mastery of perspective relied on principles of geometry and optics, often drawing from rediscovered ancient texts and contemporary advancements in understanding light. Their realistic portrayal of the human body stemmed from rigorous anatomical studies, including cadaver dissections, but also from renewed interest in physiological function. This empirical approach to understanding the physical world directly informed their artistic practices, allowing them to create images of unprecedented accuracy and depth. This same spirit of inquiry also fueled advancements in cartography and geographical exploration, reflecting an ever-expanding worldview and directly contributing to the "Age of Discovery" by providing more accurate maps and scientific illustrations. This era also saw the integration of art with scientific illustration, as artists meticulously rendered botanical and anatomical subjects, contributing to early scientific texts and anatomical atlases. It’s a beautiful testament to how art and science can inform and elevate each other, a synergy that still inspires me to think about the underlying structures of my own work, even when I'm just pushing paint around.

The Masters: My Personal Renaissance Dream Team and Beyond

You can't talk Renaissance without talking about the titans. These are the artists who didn't just paint pictures; they redefined what art could be, often with the generous backing of influential patrons. While history often spotlights the men, it's worth acknowledging the sometimes-overlooked contributions of powerful female patrons who also shaped the era, even as opportunities for female artists remained tragically limited. Sometimes I look at their work and just sigh, wondering if I'll ever achieve even a fraction of their effortless mastery, or if my own canvases will just continue their wonderfully chaotic existence, perfectly content without such grand ambition. These are the geniuses who truly brought the hallmarks of Renaissance brilliance to life.

The Italian Giants of the High Renaissance

This short, explosive period (roughly 1490-1527) gave us some of the most recognizable names in art history. It's when everything reached its peak, a burst of creative energy that still leaves me a bit breathless. What do you think, could you pick a favorite?

- Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519): The quintessential "Renaissance Man" or uomo universale. An inventor, scientist, anatomist, and, oh yes, a painter. The Mona Lisa with her enigmatic smile, The Last Supper with its incredible psychological drama. He wasn't just observing the world; he was dissecting it, understanding it, and then pouring that understanding onto his canvases, often employing sfumato – that subtle blurring of lines and colors – to create a soft, hazy atmosphere. His extensive scientific notebooks, filled with anatomical drawings (which directly informed the realism of his figures), engineering designs, and botanical studies, offer an unparalleled glimpse into his polymathic genius and show how his artistic vision was deeply integrated with his scientific and engineering pursuits. I often wonder what his studio must have looked like – probably a wonderfully messy explosion of genius, far more organized than mine, I'm sure.

- Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475-1564): My personal favorite, largely because his work feels so intensely human and powerful. A sculptor first and foremost, responsible for the magnificent David and the deeply moving Pietà. His ability to render the human form with such muscularity and emotional weight, whether in marble or fresco, is unparalleled. Then there's the Sistine Chapel ceiling, a monumental feat he famously didn't want to do, but which became one of the greatest artistic achievements of all time, despite the immense physical challenges of working on scaffolding for years. And as if that weren't enough, he was also a gifted poet and an architect, famously contributing to the dome of St. Peter's Basilica and designing the Laurentian Library, further cementing his "Renaissance Man" status. His ability to evoke emotion and life from cold marble or a vast ceiling is, frankly, intimidating; I sometimes stare at a blank canvas and wonder if he ever just shrugged and said, "Eh, good enough."

- Raphael Sanzio (1483-1520): The master of harmony and grace. His Madonnas are famously serene and beautiful, and his frescoes in the Vatican's Stanze della Segnatura (like The School of Athens) are masterpieces of composition and philosophical depth. He brought a sense of calm perfection to the High Renaissance, a beautiful counterpoint to Leonardo's intellectual curiosity and Michelangelo's raw power.

The Luminous World of the Venetian Renaissance

While Florence and Rome dominated the High Renaissance with their emphasis on disegno (drawing and sculptural form), Venice emerged as a distinct and influential center, known for its unique artistic approach. The Venetian Renaissance prioritized rich color (colore or colorito) and luminous light over the Florentine and Roman emphasis on line and structure. Venetian artists embraced the sensuality of paint, creating works filled with glowing light, deep shadows, and luxurious textures. This emphasis on color was influenced by Venice's unique, shimmering light (reflected off its canals and lagoons), its thriving trade routes which brought exotic and vibrant pigments from the East, and its historical ties to Byzantine mosaics, which favored rich, luminous surfaces and contributed to Venice's distinct aesthetic through the use of gold leaf and intricate iconographic traditions. Masters like Giovanni Bellini (c. 1430–1516), Giorgione (c. 1477/8–1510), and especially Titian (c. 1488/90–1576) defined this style, influencing generations of artists with their innovative use of oil paint and their captivating portrayal of landscape and the human form. If you're fascinated by the use of color, our definitive guide to color theory in art delves deeper into this fascinating subject.

The Northern Renaissance: Intimacy, Detail, and Symbolism

While the Italian Renaissance, with its focus on humanism, classical revival, and monumental works, often grabs the spotlight, it's essential to remember its northern counterpart. The Northern Renaissance, flourishing in areas like Flanders, the Netherlands, and Germany, had its own distinct flavor. It was characterized by incredible, almost microscopic detail, the pioneering use of oil paint (often earlier than in Italy), and a focus on everyday life, intense religious symbolism, and often, a more somber or introspective mood. This distinct approach was often driven by different societal and economic forces than in Italy, including a thriving merchant class and robust trade networks (which fueled a demand for new forms of art catering to a broader, often more private, clientele) and the unfolding religious reformations.

Artists like Jan van Eyck (c. 1390-1441) achieved unparalleled realism and luminous color through their mastery of oil in works like the Ghent Altarpiece, while Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528) revolutionized printmaking, spreading ideas and imagery across Europe with his intricate engravings. Figures like Hieronymus Bosch (c. 1450-1516) explored complex moral allegories and fantastical landscapes in works like The Garden of Earthly Delights (with its wild, surreal imagery), and Pieter Bruegel the Elder (c. 1525-1569) captured the everyday life of peasants with profound humanity in scenes like Peasant Wedding. It shows that even a "rebirth" had many different, equally captivating expressions across the continent, often with a more intimate, spiritual pulse and a strong emphasis on domesticity rather than grand public works.

A Journey Through Time: Early, High, and Late Renaissance

To truly appreciate the dynamism of this era, it's helpful to understand its progression through distinct phases, each building on the last while forging new artistic directions.

- Early Renaissance (c. 1400-1490): Centered primarily in Florence, this period saw the foundational innovations in linear perspective, naturalism, and a renewed interest in classical forms. Masters like Masaccio, Donatello, and Botticelli laid the groundwork, experimenting with new ways to depict reality and human emotion, moving decisively away from medieval conventions. It was an era of intense experimentation and intellectual ferment.

- High Renaissance (c. 1490-1527): This relatively brief but incredibly fertile period, largely centered in Rome and Florence, represents the pinnacle of Renaissance art, characterized by a pursuit of idealized beauty, harmony, and balance. It gave us the giants: Leonardo, Michelangelo, and Raphael, who brought an unprecedented level of emotional depth, technical mastery, and compositional perfection to their works. Their art embodied the uomo universale ideal.

- Late Renaissance & Mannerism (c. 1520-1600): As the High Renaissance achieved what felt like perfection, artists began to seek new forms of expression. Mannerism emerged as a distinct style, consciously breaking with the harmony and balance of the High Renaissance. Mannerist artists like Pontormo, Bronzino, and Parmigianino often emphasized elongated forms, artificial, often twisting poses (like the serpentinata), dramatic and sometimes unsettling compositions, and heightened emotional intensity. It was a move away from naturalism towards a more stylized and intellectually complex aesthetic, paving the way for the Baroque period that followed. It's like when a genre becomes so good, artists have to break the rules to find new ways to surprise you – sometimes it works, sometimes it’s a bit much, but it’s always interesting, don't you think? You can explore this further by understanding art history's key periods.

From the intimate details of Northern realism to the grandeur of Italian frescoes, the Renaissance truly offered a spectrum of human expression. And to truly grasp its magic, sometimes you just need to see it for yourself.

Where to Witness the Magic: My Dream Museum Tour (and Yours!)

If you ever get the chance, seeing these works in person is an entirely different experience. The sheer scale, the intricate textures, the way the light hits them, the palpable history – it's transformative. Crucially, this continued access is a testament to the tireless efforts of conservationists and art restorers who work to preserve these fragile masterpieces for future generations, allowing us to still marvel at their original brilliance. Here are a few places I dream of revisiting (or visiting for the first time!) to soak in the Renaissance magic, and perhaps feel that ancient awe myself, a curated itinerary for anyone seeking that powerful connection:

- The Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy: Home to Botticelli's Birth of Venus and Primavera, along with masterpieces like Leonardo's Annunciation. Florence is the cradle of the Renaissance, and this gallery is its beating heart. Walking its halls feels like stepping back in time to where it all began, a truly visceral experience, making me feel like an excited kid in a candy store for history.

- The Vatican Museums, Vatican City: Where else can you see the Sistine Chapel ceiling and Raphael's Stanze under one roof? It's an overwhelming, awe-inspiring experience, a testament to the immense power and influence of art, and a definite bucket-list destination, where the sheer audacity of human creativity feels almost divine. Don't miss the Laocoön Group sculpture, a Roman masterpiece that profoundly influenced Renaissance artists.

- The Louvre Museum, Paris, France: Naturally, the Mona Lisa resides here, drawing crowds, but you'll also find incredible works by Raphael, Titian, and many others, including Veronese's colossal The Wedding Feast at Cana, offering a broader view of the period's influence beyond Italy, reminding me how art truly transcends borders.

- The National Gallery, London, UK: A fantastic collection that spans the entire period, with works by Botticelli (Venus and Mars), Leonardo (Virgin of the Rocks), Michelangelo, and many more. It's wonderfully accessible, allowing for a comprehensive journey through the chronological development of the Renaissance without having to hop across countries. A real treasure trove for any art lover, and perhaps a perfect place to start if you're feeling overwhelmed by choice.

- The Prado Museum, Madrid, Spain: While perhaps better known for its later Spanish masters, the Prado holds an exceptional collection of Italian Renaissance and Northern Renaissance works, particularly from Titian (Bacchanal of the Andrians) and Raphael, reflecting Spain's significant patronage during the era. It’s a wonderful place to see how these influences spread, offering a rich perspective on the global reach of the Renaissance – even in places you might not initially expect.

And for a different kind of art experience, don't forget you can always visit my museum in 's-Hertogenbosch for a taste of the contemporary! It's always a good idea to juxtapose the old with the new, to truly see how far we've come, and perhaps how little has truly changed.

Beyond the Canvases: Renaissance Art in My World

After diving into the lives and works of these giants, a natural question arises: what does all this mean for an artist like me, who often dives into abstraction and vibrant color? A lot, actually. The Renaissance's profound focus on composition, balance, and the emotional impact of a piece continues to inform everything I do, even if my finished work looks vastly different. The idea that art can convey profound human truths, or simply evoke a deep feeling, is a timeless lesson they perfected. It reminds me that even when I'm just playing with color and form, there's always an underlying structure and intention, a desire to connect. Their meticulous observation of the natural world, even for figurative works, teaches me how to look, to truly see, and then to reinterpret that seeing in my own abstract language. For instance, the Renaissance emphasis on dynamic composition, like the triangular stability seen in many Madonnas, or the dramatic use of chiaroscuro to guide the eye, profoundly influences how I arrange abstract shapes and colors to create movement and depth, even without a literal vanishing point, guiding the viewer's gaze through my own vibrant landscapes of emotion. Perhaps the greatest takeaway is the spirit of relentless inquiry and technical mastery – a drive to understand the world and then translate that understanding into something beautiful and meaningful. It's a foundational understanding that empowers everything from [abstract art](/finder/page/the-definitive-guide-to-the-history-of-abstract-art-key- движении-artists-and-evolution) to my own contemporary pieces. Sometimes, I even find myself channeling a bit of that Renaissance virtù when I tackle a particularly challenging canvas, pushing myself to find that perfect balance, hoping my abstract expression captures even a fraction of their depth.

When I look at a piece like Matisse's The Red Room, I see a similar fearless use of color and a bold approach to composition that, while abstracting reality, still speaks to a deep human experience – much like the emotional resonance of a Renaissance portrait, just with more… red. Or consider a work by Gerhard Richter. The deliberate arrangement of color in 1024 Colors might seem miles away from the Renaissance, but the underlying quest for visual harmony and impact, and even a certain mathematical precision, feels like a distant echo of those earlier masters' pursuits.

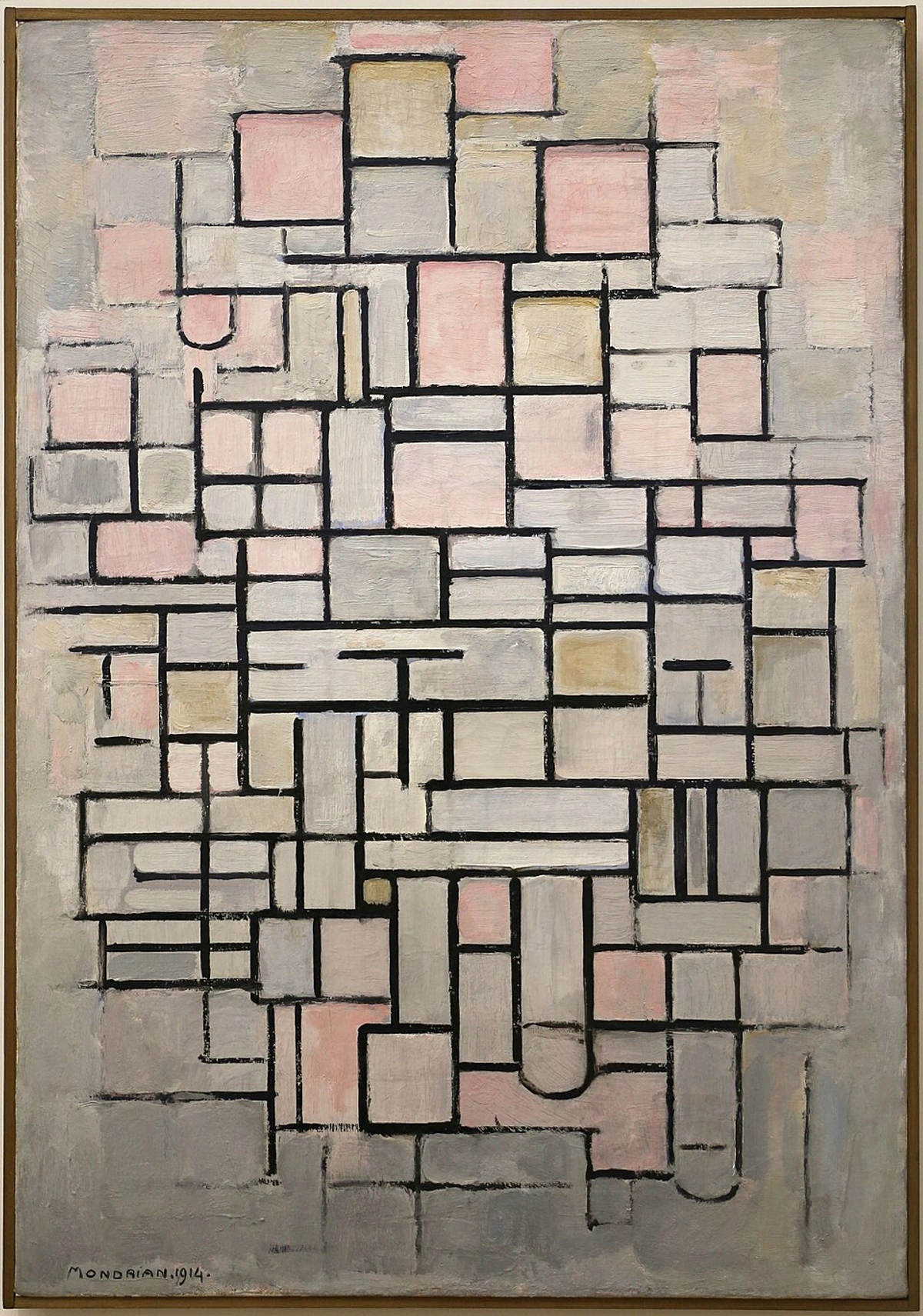

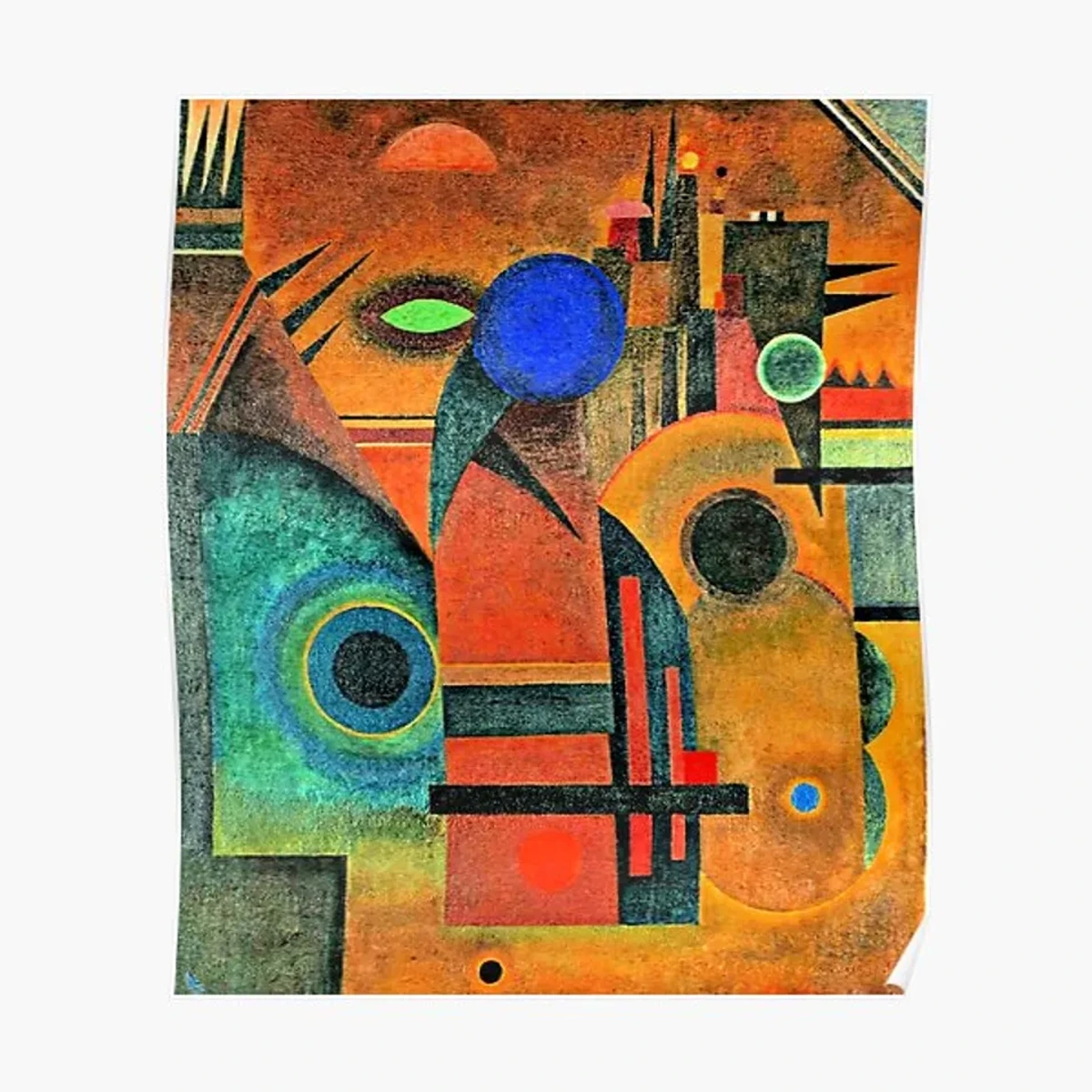

The structured chaos of a Mondrian, or the expressive strokes of a Kandinsky, in their own ways, are still grappling with the same questions of form, emotion, and perception that preoccupied Leonardo and Michelangelo. They're just using a different vocabulary. It's about finding that core truth, whether it's through hyper-realistic anatomy or a splash of paint that perfectly captures a feeling.

If you find yourself inspired to bring a touch of that thoughtful impact into your own space, perhaps in a more contemporary form, feel free to explore my contemporary colorful art.

Frequently Asked Questions About Renaissance Art

If all this talk of masterpieces and personal journeys has sparked your curiosity and left you with lingering thoughts, you might have some questions. Let's tackle a few common ones:

Q1: What's the biggest misconception about Renaissance art?

A: I think many people assume it's only religious. While Christianity played a huge role, the Renaissance was also about secular subjects like mythological scenes (Botticelli's Birth of Venus), portraiture (of wealthy merchants and nobility), and a deep interest in human anatomy and science. It was a broadening of horizons, not just a continuation of religious themes. You can learn more about symbolism in art in general.

Q2: How did Renaissance art vary across different Italian regions?

A: Absolutely not all Italian Renaissance art was the same! While sharing common goals, regional schools developed distinct characteristics:

- Florentine School: Often prioritized disegno (drawing, precise form, intellectual composition, clear lines) and sculptural qualities, emphasizing rational design and monumental figures. Think of Botticelli's precise lines or Michelangelo's muscular forms.

- Venetian School: Championed colore (color, light, atmospheric effects, sensuality, rich textures). Artists like Titian used oil paint to create luminous, vibrant works with soft transitions and an emphasis on the interaction of light and shadow, reflecting the unique environment of Venice.

- Lombard School: Heavily influenced by Leonardo's naturalism and psychological depth, often produced works with a more intimate and emotive character, characterized by subtle transitions of light and shadow (sfumato), and a focus on realism in portraiture, as seen in works by Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio.

- Umbrian School: With artists like Perugino, focused on serene, ordered compositions, often set in tranquil, idealized landscapes, which greatly influenced younger artists like Raphael.

It's truly a testament to individual genius operating within a shared cultural moment.

Q3: How did Renaissance art influence later movements?

A: It laid the groundwork for almost everything that followed! The mastery of perspective, anatomy, and emotional expression became the standard against which all subsequent art was measured. You can trace its influence through Baroque, Neoclassicism, and even see echoes of its principles in how artists approach composition and form today, even in movements like [abstract art](/finder/page/the-definitive-guide-to-the-history-of-abstract-art-key- движении-artists-and-evolution).

Q4: Why is it called "Renaissance"?

A: As I mentioned earlier, it means "rebirth" in French. Historians (much later) used this term to describe the period's profound rediscovery and revitalization of classical learning, art, and philosophy after what they perceived as the intellectual stagnation of the Middle Ages. It was a conscious looking back to the 'golden ages' of Greece and Rome, but with a new, vibrant European spirit.

Q5: What role did technology play in the Renaissance?

A: Beyond the obvious artistic techniques, the invention of the printing press by Gutenberg in the mid-15th century was revolutionary. It allowed for the widespread dissemination of classical texts, scientific diagrams, anatomical drawings, and artistic prints, making knowledge cheaper and more accessible, thus accelerating the exchange of ideas and influencing artistic styles across Europe far more rapidly than before. This technological leap was instrumental in fostering the intellectual and cultural ferment of the era. Furthermore, advancements in pigment production, such such as more stable and vibrant colors derived from new sources (like the introduction of ultramarine), and the development of new tools for sculpture and painting, also contributed significantly to the artistic capabilities of the period.

Q6: What was the role of women in Renaissance art?

A: While opportunities for female artists were tragically limited due to societal norms and exclusion from workshops and academies, women played crucial roles as patrons. Figures like Isabella d'Este (Marchioness of Mantua) and Caterina Sforza actively commissioned works, collected art, and fostered intellectual circles, significantly shaping the artistic landscape. Some exceptional female artists, like Sofonisba Anguissola (known for her vivid portraits such as Self-Portrait at the Easel) and Lavinia Fontana (a successful portraitist and painter of religious scenes like Noli me Tangere), did achieve recognition, primarily in portraiture, though they often faced greater hurdles than their male counterparts. Their stories remind us of the talent that might have flourished had societal barriers been less restrictive.

Q7: What came after the Renaissance?

A: The High Renaissance, with its pursuit of idealized harmony and balance, gradually transitioned into Mannerism in the mid-16th century, which I touched on earlier. Mannerism emerged partly as a reaction against the perceived perfection achieved by High Renaissance masters, as artists sought new ways to express themselves. They often aimed for greater emotional expression and intellectual complexity, emphasizing elongated forms, artificial, elegant poses, dramatic lighting, and often unsettling compositions, moving away from naturalism towards a more stylized and emotionally intense aesthetic. Think of Parmigianino's Madonna with the Long Neck with its distorted proportions. This diverse range of artistic interpretations across Europe then paved the way for the dramatic and dynamic Baroque period that followed.

My Renaissance, Your Renaissance: A Concluding Thought

Looking at Renaissance art sometimes makes me feel a bit lazy. These guys were pushing boundaries, inventing techniques, and creating works that still awe us centuries later. It's a humbling reminder of human ingenuity and resilience, a testament to what humans can achieve when they truly embrace their potential. It makes me chuckle, thinking about their relentless drive, while I sometimes struggle to decide between two shades of blue and then give up and just splat both on the canvas. But it also inspires me, reminding me that every artist, in their own time, is trying to say something, to connect, to make sense of the world around them. The relentless pursuit of understanding, whether through anatomy or abstract expression, is a shared human endeavor.

It’s a journey, much like my own artistic journey, where every step builds on the last, learning from the past to shape the future. The Renaissance didn't just transform its own era; it permanently shaped the trajectory of Western visual culture, setting benchmarks for artistic excellence and human-centered inquiry that continue to echo today. So, next time you see a Renaissance painting, don't just see a historical artifact. See a vibrant conversation across centuries, a testament to what we, as humans, are capable of when we truly open our eyes and minds. What echoes of this grand 'rebirth' do you find resonating in the art, ideas, or even just the curious corners of your own contemporary world? I'd love to know what sparks your own personal Renaissance.

Thank you for joining me on this personal dive into a truly monumental period.