Performance Art Unveiled: A Personal Journey Through Its Radical History

An artist's introspective guide to performance art's evolution. Explore its avant-garde roots, body art, social sculpture, and digital future, challenging perceptions of what art can be and how it connects to our lives.

The Unwritten Script: A Personal & Comprehensive Guide to Performance Art's History & Evolution

There are some art forms that just… get under your skin. For me, performance art is one of those. It’s not always neat, rarely comfortable, and often leaves you asking, 'Wait, what was that?' But that’s precisely its charm, isn’t it? It demands something of you, a different kind of engagement than staring at a painting on a wall. Its very nature is ephemeral – a fleeting, unrepeatable moment that lives on only in our collective memory, through documentation, and in the rich conversations it sparks. Much like life itself, I suppose, and like a particularly vivid dream you can't quite articulate but profoundly feel. This journey is my attempt to untangle that fascination, to demystify a form often seen as intimidating, and to offer a personal, comprehensive guide to its fascinating evolution, unveiling the radical heart of live art.

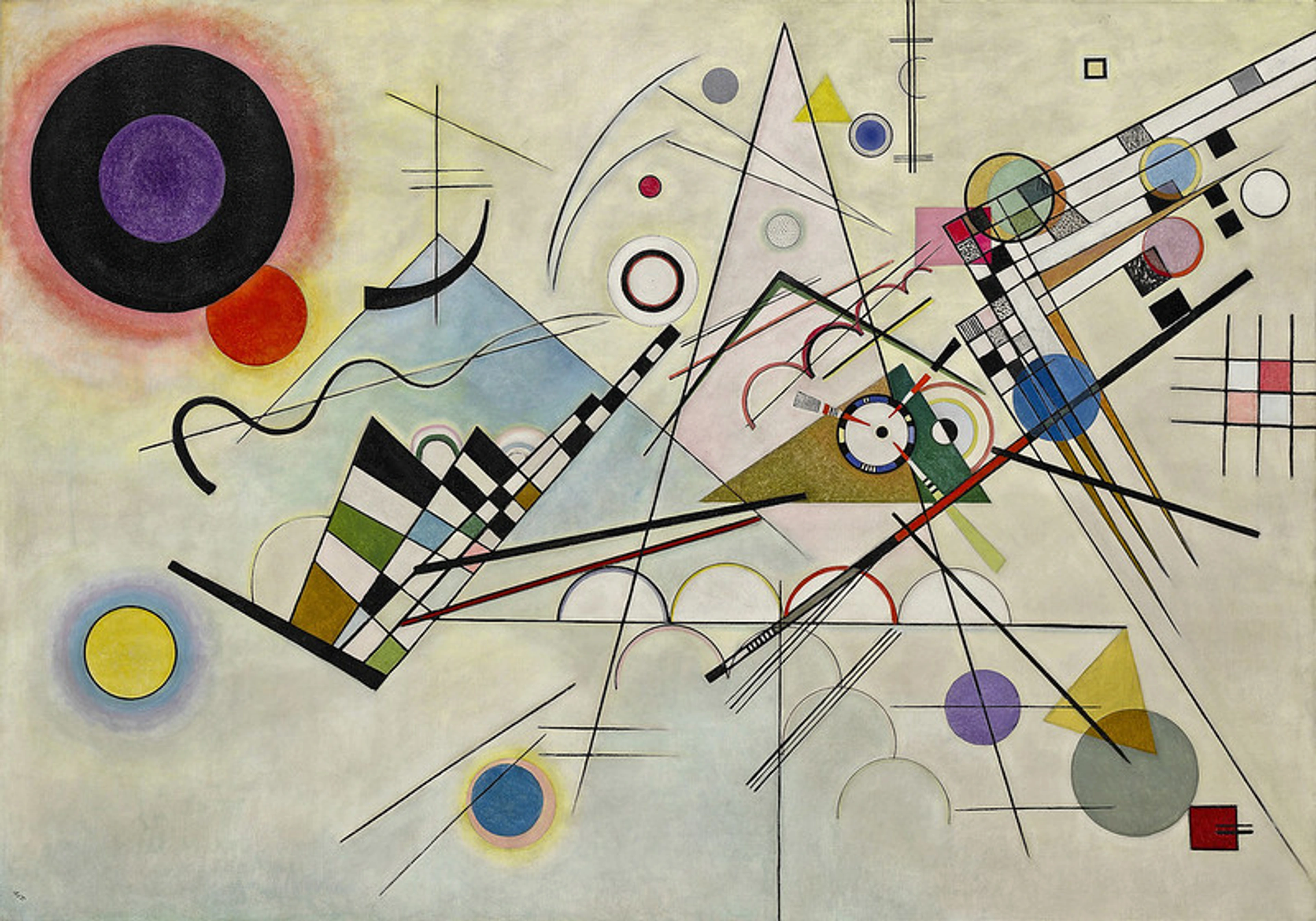

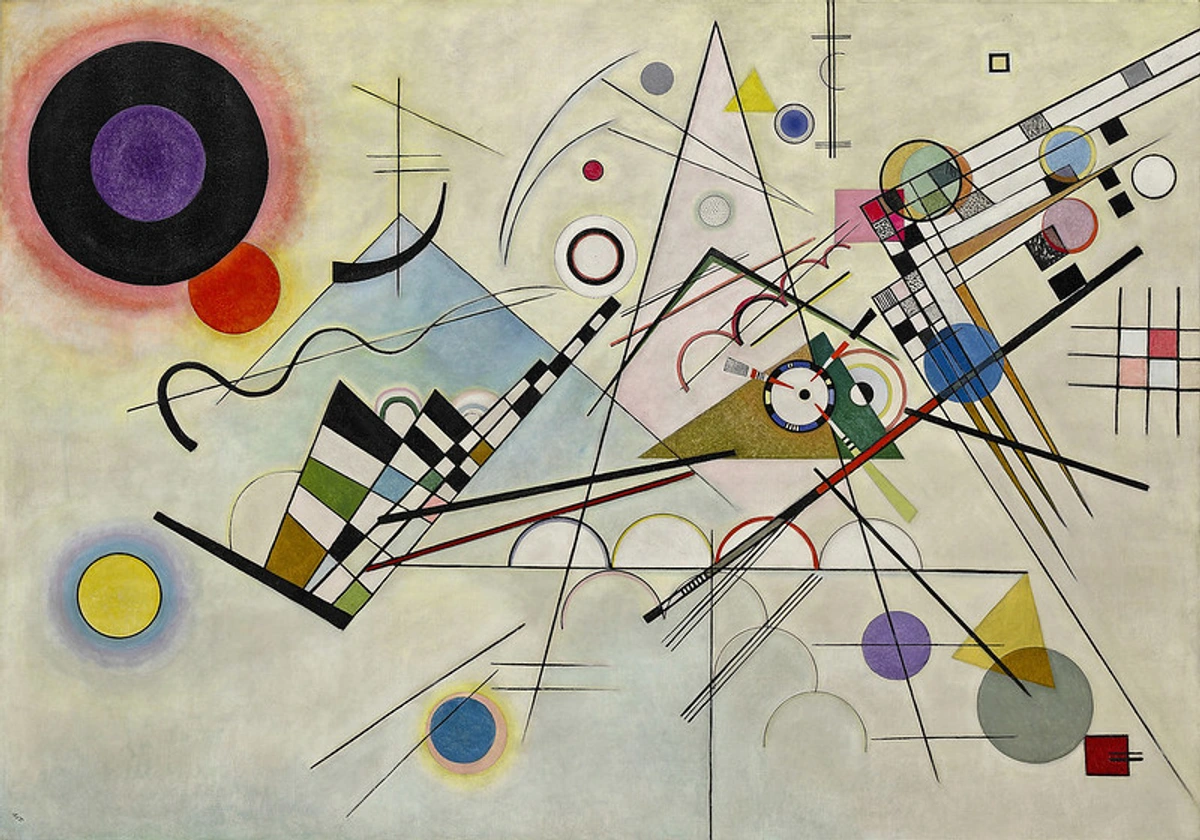

My own art, while often abstract and vibrant, strives for a certain kind of immediate connection, a palpable presence. It’s a quiet dialogue, a dance of color and form, that I pour myself into, much like a dancer pours themselves into a movement. Performance art takes that 'presence' and turns it up to eleven, using the body, time, and space as its canvas. It's a deeply personal form, and as someone who pours a lot of myself into my creative timeline, I find a strange kinship with artists who literally put themselves on the line, making the process as visible and vital as any final outcome. In this guide, we'll explore its anarchic beginnings, its radical shifts, and its constant, vibrant redefinition of what art can truly be, offering a new lens through which to view the process behind my own abstract works.

What Even Is Performance Art? (And Why Does It Keep Calling to Me?)

Let’s be honest, the term 'performance art' can sound a bit intimidating, conjuring images of artists doing strange, sometimes shocking, things. (Believe me, I've had similar reactions to some of my own early abstract experiments!) But at its heart, it's fundamentally straightforward: art created through actions performed by the artist or other participants. It’s live, temporary, and usually presented to an audience. While it often blurs lines with avant-garde theatre, conceptual art, and even dance, performance art's unique core lies in the artist's direct physical presence as the primary medium, prioritizing the event and experience over conventional theatrical illusion or choreographed narratives. Unlike traditional theatre, which typically follows a script, characters, and a narrative to tell a fictional story, performance art often doesn't rely on these conventions. Instead, it prioritizes the event, the concept, and the direct experience over theatrical illusion, choreographed beauty, or conventional entertainment, often making the thought itself the artwork.

While it shares elements with other live forms, performance art distinguishes itself by often lacking the narrative structure of theatre, the formalized movements of dance, or the musical conventions of opera. Its focus is less on portraying a fictional story and more on the raw, unmediated act itself, often rooted in a conceptual idea or a personal statement. It's the difference between watching a story unfold and witnessing an experience being created in real-time. For me, it's the sheer breadth of possibilities that truly captivates. What hidden performances might be waiting to unfold in our own everyday routines, if only we chose to see them?

It prioritizes direct engagement and often incorporates audience participation, making them not just spectators but sometimes integral to the work. This participation can exist on a spectrum: from passive witnessing (where the audience's presence is acknowledged but not actively required), to direct interaction (where artists might invite reactions or specific gestures), to active co-creation (where the audience's actions genuinely shape the outcome of the piece, becoming collaborators in the artwork itself). This dynamic, evolving relationship with the audience is a cornerstone of the form, creating a unique, shared moment. Think of it as a form of live art that prioritizes the event over the object.

Think of durational performance, where the act unfolds over hours, days, or even months, pushing the boundaries of human endurance and audience engagement. But it can also be a simple gesture, a silent procession, or a carefully orchestrated happening that blends into everyday life. It can involve elaborate costumes and props, or nothing at all, using just the artist's body as the canvas. Body art, for example, often uses the artist's physical self as the subject and medium, sometimes in extreme ways to convey a message. The addition of sound (whether music, spoken word, or ambient noise) and lighting further shapes the experience, turning space into a dynamic, living artwork. Crucially, the intent behind performance art is often not conventional entertainment, but rather to provoke thought, challenge perceptions, or critique societal norms – a profound form of social commentary and often activism.

I’ve always been fascinated by things that challenge our perceptions. Why does art have to be a static object? What if the art is the doing? It's a question I ponder when I’m deeply immersed in a new piece, wondering if the true art is in the final product or the process of creation itself. Performance art leans heavily into that process, making the act of creation or interaction the primary event. It's about presence, direct engagement, and sometimes, a deliberate disruption of expectations, much like how a bold stroke of color can disrupt a quiet composition.

Early Seeds of Disruption: Avant-garde Movements

But where did this radical approach to art begin? Its roots are deeply embedded in the avant-garde movements that sought to shatter artistic conventions. Every revolution starts somewhere, often with a mischievous twinkle in the eye and a profound dissatisfaction with the status quo. For performance art, those seeds were sown in the early 20th century, a time of immense social and artistic upheaval, particularly in the wake of industrialization and the devastation of World War I. Artists looked at traditional painting and sculpture and thought, 'This isn't enough. This isn't real enough. It doesn't capture the chaotic energy, the psychological scars, or the urgent need for new expressions in our times.' Even early avant-garde theatre, like Alfred Jarry's scandalous Ubu Roi (1896), paved the way by shocking bourgeois audiences and dismantling theatrical conventions, hinting at the visceral disruptions to come. Even Symbolism, with its emphasis on evoking mood and inner experience through suggestive, non-realistic means, provided an early philosophical groundwork for art that moved beyond literal representation and into more subjective, performative, and symbolic gestures.

The emotional intensity and subjective expression of Expressionism (active broadly from 1905-1920s) also subtly prepared the ground. Artists like the German Expressionists sought to convey raw psychological states rather than objective reality, often leading to distorted forms and heightened emotionality. This focus on internal experience and its outward, often exaggerated, manifestation resonated directly with the later, more direct, emotional expressions seen in performance art, using the body itself as a vehicle for raw, visceral communication. To learn more about this influential period, explore our Ultimate Guide to Expressionism.

Futurism: Speed, Sound, and Confrontation

The Futurists, for example, were obsessed with speed, technology, and dynamism, but also aimed to shock bourgeois audiences and break down the separation between art and life. Their "serate futuriste" (futurist evenings) were theatrical provocations, often involving shouting manifestos, noise music, and direct audience confrontation – moments that verged on pure performance. Imagine Marinetti, the movement's founder, reciting inflammatory poetry like his "Zang Tumb Tumb," with its onomatopoeic sounds and disrupted syntax, perhaps even inciting a riot by declaring war on the past; this was a deliberate strategy to dismantle passive spectatorship. They even experimented with "parole in libertà" (words in freedom), disrupting traditional syntax to create new, dynamic poetic expressions, directly influencing experimental text-based performance. To delve deeper into their revolutionary ideas, you might enjoy The Impact of Futurism on Modern Art and Design.

Dada: Anti-Art and the Absurd

But the real game-changers, for me, were the Dadaists. Born from the disillusionment of World War I, their anti-bourgeois sentiment fueled a radical rejection of established artistic and social norms. At places like the infamous Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich, they were performing nonsensical poetry, wearing bizarre costumes, and generally trying to dismantle the very idea of 'art' as something precious and polite. Imagine Hugo Ball performing his sound poems, primal vocalizations that defied traditional language, amid a cacophony of music and other simultaneous performances; this embodied the Dadaist spirit of anti-art, of challenging norms and embracing the absurd. I remember stumbling upon a grainy documentary about Dada performances years ago, and my first thought was a mix of bewilderment and a strange, almost giddy admiration. It felt like watching someone smash a beautiful, fragile vase, not out of malice, but to see what new forms the shards might create. It was disorienting, exhilarating, and frankly, a little confusing – much like trying to understand the intent behind a particularly abstract brushstroke when you're first learning about art. If you want to dive deeper into their wonderfully chaotic world, you might enjoy reading about The Enduring Influence of Dadaism on Contemporary Art and its Legacy.

Surrealism and Bauhaus: Dreams and Experimentation

Even Surrealism, with its exploration of the subconscious, dreams, and irrational acts, often spilled into the performative. Think of André Breton's "automatic writing" as a mental performance, or the bizarre, carefully staged events and "happenings" they orchestrated, designed to jolt the viewer into new realities. Salvador Dalí, for instance, famously gave lectures in a diving suit, almost suffocating, to highlight the depths of the subconscious – a clear performative act. Delve into their dream-like world with our Enduring Legacy of Surrealism. The experimental theatre workshops at the Bauhaus school also contributed, exploring movement, light, and sound in ways that pushed beyond conventional stagecraft, with figures like Oskar Schlemmer transforming dancers into abstract, geometric figures in works like his 'Triadic Ballet,' radically departing from traditional narrative ballet. It was a time of boundless, sometimes reckless, experimentation. What kind of artistic chaos would you unleash to shake things up if tradition felt like a cage? Perhaps a splash of unexpected color on a canvas, or a spontaneous gesture in public?

Movement | Key Contribution to Performance Art |

|---|---|

| Dada | Anti-art spirit, absurdity, cabaret performances (Cabaret Voltaire with simultaneous verse and bizarre costumes), sound poetry, challenging norms, anti-bourgeois sentiment |

| Futurism | Theatrical provocations ("serate futuriste" with manifestos and audience confrontation), dynamism, "parole in libertà", breaking art/life separation |

| Surrealism | Exploration of subconscious, irrational acts, staged events, automatic writing, jarring public interventions (e.g., Dalí in a diving suit) |

| Bauhaus | Experimental theatre, exploration of movement, light, and sound; abstract choreography (e.g., Oskar Schlemmer's Triadic Ballet) |

| Symbolism | Early philosophical groundwork for non-literal, evocative, and suggestive art, paving way for abstract and performative gestures; focus on subjective experience. |

| Expressionism | Emphasis on subjective experience, emotional intensity, psychological states, and their exaggerated outward manifestation; raw, visceral energy in artistic output. |

Post-War Explosions: From Gutai to Happenings

The early 20th century’s artistic rebellions against the status quo set the stage, but the mid-20th century brought another seismic shift. After World War II, with its unimaginable destruction and the urgent need for society to rebuild, a new generation of artists felt an even greater urgency to break free from tradition, to create art that directly engaged with a scarred and rebuilding world. This era echoed that earlier dissatisfaction but with a raw, post-cataclysmic intensity, championing the ephemeral and prioritizing the live experience above all else. Before Gutai, even the raw, physical energy of Action Painting – where the act of creation, the artist's engagement with the canvas, became as important as the finished piece – hinted at the performative turn to come, making the process central. This focus on the artist's physical engagement with the canvas, the very act of creation, foreshadowed performance art's embrace of the ephemeral and the artist's direct presence. Simultaneously, the rise of Conceptual Art in Europe further influenced performance, as artists prioritized the underlying idea or concept above any material form, often seeing the performance itself as the most direct means to convey these intellectual propositions.

The Radical Act of Gutai

This is where the Japanese Gutai group comes in, and oh, how I love their audacity! Active from the mid-1950s, these artists created incredibly physical, often destructive, and deeply philosophical 'actions.' Imagine artists wrestling with mud (like Kazuo Shiraga's Challenging Mud), smashing through paper screens, or even standing still to let rain mark their bodies. They believed in the spirit of creation being intertwined with the destruction of materials, pushing the boundaries of what a painting or sculpture could be. Their raw, immediate physicality and exploration of presence resonate deeply with my own desire for a palpable connection in art. They were truly pioneers in action painting and early performance art, paving the way for so much that followed, inspiring later movements like Arte Povera in Italy, which used everyday, 'poor' materials in performative installations to challenge consumerism and traditional art forms. You can explore more about their fascinating legacy in The Legacy of Gutai: Japan's Radical Post-War Art Movement. Just imagine the sheer visceral impact of witnessing such raw, immediate creation!

American Happenings and Fluxus

Across the globe, in America, artists like Allan Kaprow, influenced by John Cage’s experimental music, were orchestrating 'Happenings.' These were loosely structured events, often involving the audience in unpredictable ways, that blurred the lines between art and everyday life. Think of people performing mundane tasks, or interacting with objects in unexpected ways, all within a specific time and place. It wasn't about a polished performance; it was about the experience itself, the fleeting interaction and often active audience participation. It reminds me of those moments in life that are entirely unscripted, yet somehow profound, like catching a glimpse of a perfect cloud formation or a sudden, unexpected downpour. These moments questioned the very definition of an artwork, making the fleeting experience the art itself.

This era also saw the rise of Fluxus, an international network of artists who, like the Dadaists, delighted in anti-art, everyday objects, and unexpected 'events,' further expanding the boundaries of performance and conceptual art. Their 'scores' or 'event poems' provided instructions for simple, performative actions, often blurring the line between art and life even further. For example, George Maciunas, a central figure, might offer a score like 'Draw a straight line and follow it,' or perhaps a piece like George Brecht's "Drip Music," where water slowly drips into a container, inviting contemplation on time and sound. Other Fluxus artists, like Yoko Ono with her "Cut Piece" instructions (though often performed by her), or Nam June Paik's early experiments with television and performance, further exemplify the movement's embrace of conceptual instructions and everyday actions as art. It's a testament to the idea that art isn't just confined to galleries; it's intricately woven into the fabric of our everyday perceptions if we just allow ourselves to look. Perhaps in the quiet rhythm of your own breath, or the subtle dance of shadows on a wall.

Challenging the System: The 60s and 70s

The social and political turmoil of the 1960s and 70s saw performance art become even more direct, more political, and often, more personal. Fueled by widespread social movements (civil rights, anti-war, feminism) and a general desire to challenge authority, artists began using their own bodies as the primary medium, exploring themes of identity, pain, gender, and societal constraints with a new, uncompromising intensity. This period was marked by a strong sense of political and social activism, with artists using their actions to critique war, protest injustices, and demand change. These were truly brave and often visceral statements, forcing viewers to confront uncomfortable truths about themselves and the world. The continued rise of Conceptual Art during this period also profoundly influenced performance, as artists prioritized the idea or concept behind the work above its material form, often using performance as the most direct means to convey these concepts, making the thought itself the artwork. This era wasn't just about breaking boundaries; it was about smashing them with a purpose.

Body Art: Confrontation and Vulnerability

Body Art was raw, often visceral, and deeply confrontational. Artists like Chris Burden would subject themselves to extreme physical feats or self-inflicted pain (e.g., being shot in Shoot or crucified on a Volkswagen Beetle in Trans-Fixed) to comment on violence, vulnerability, societal control, or the power dynamics between artist and audience. Vito Acconci, for instance, in his famous 1972 piece Seedbed, used his body and voice beneath a gallery floor to engage directly and uncomfortably with visitors above, exploring themes of public and private space, voyeurism, and intimacy. Marina Abramović, too, began her groundbreaking Rhythm series in the early 1970s, pushing her physical and mental limits to the extreme, sometimes inviting audience participation in potentially dangerous ways (e.g., Rhythm 0, where she offered herself as an object for the audience to use 72 items on her body, testing the limits of human nature). Witnessing such an act, even through documentation, forces a confrontation with one's own discomfort and complicity. I can't imagine putting myself through some of what they did – the sheer vulnerability and risk – but I deeply respect the courage and the profound, often uncomfortable, message behind it. (Honestly, I'm quite happy to leave the extreme physical endurance to the professionals, and stick to my canvas battles!) These works raised critical ethical considerations about the artist's boundaries, the audience's role in witnessing such extreme acts, and the potential for exploitation. These works continue to challenge our definitions of suffering, resilience, and artistic expression. How much are we willing to endure, or witness, for the sake of a profound message?

Joseph Beuys and Social Sculpture

Simultaneously, the German artist Joseph Beuys expanded the definition of performance art with his concept of "social sculpture." For Beuys, every human action could be art, and society itself was the greatest artwork we could collectively shape through creative acts. His "actions" (performances) often involved lecturing, explaining his complex theories, or engaging in symbolic rituals with materials like felt and fat – chosen for their insulating and organic, transformative qualities, symbolizing warmth, protection, and the potential for change. In his iconic 1965 action How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare, Beuys covered his head in honey and gold leaf, cradling a dead hare while silently moving through a gallery, whispering explanations of the artworks to the animal. This deeply symbolic, mysterious act questioned the nature of communication and rationality within art, often incorporating elements of activism and healing. He famously declared, "everyone is an artist," shifting the focus from the finished object to the transformative potential of human creativity and participation, making the process of human interaction and transformation a central performative act.

Feminist Performance Art: Reclaiming Narratives

Feminist Performance Art emerged powerfully during this era. Artists like Carolee Schneemann, Yoko Ono, and Valie Export used their bodies to challenge patriarchal norms, expose inequalities, and specifically reclaim the female body as a site of artistic and political agency. Ono's iconic Cut Piece (1964) invited audience members to cut off pieces of her clothing, a powerful and vulnerable exploration of trust, gender, and objectification. Carolee Schneemann, in works like Interior Scroll (1975), literally pulled a text from her vagina, publicly confronting taboos surrounding the female body, sexuality, and artistic expression. Austrian artist Valie Export, through her confrontational street performances like 'Tapp- und Tastkino' (Tap and Touch Cinema), directly engaged with public space to challenge gender roles and objectification by inviting passersby to touch her breasts behind a curtain. Artists within collectives like the Womanhouse project also explored domesticity and female experience through performative installations. Their work was often confrontational, beautiful, and deeply moving, forcing viewers to confront uncomfortable truths and give voice to experiences that had long been marginalized. It truly makes you wonder: what are we still unwilling to confront in ourselves or society, and how might art help us do so? This era also saw the performative aspects of Land Art, where the artist's action in a specific landscape, often documented, became integral to the work, emphasizing process and ephemeral interaction with nature.

Movement / Focus | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Body Art | Use of artist's own body, extreme physical acts, self-inflicted pain, exploring vulnerability and power dynamics, ethical considerations (e.g., Vito Acconci's Seedbed, early Marina Abramović's Rhythm series) |

| Feminist Performance | Challenging patriarchal norms, reclaiming female narratives, exploring gender and objectification, reclaiming the female body (e.g., Yoko Ono's Cut Piece, Carolee Schneemann's Interior Scroll, Valie Export's 'Tapp- und Tastkino') |

| Social Sculpture | Every human action as art, society as the artwork, transformative potential of creativity, symbolic rituals using symbolic materials (e.g., Joseph Beuys's How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare), often with activist intent. |

| Conceptual Art | Prioritizing the idea or concept over material form, using performance to convey intellectual propositions; the idea itself is the artwork. |

| Land Art | Artist's actions within a specific environment, often documented, emphasizing process and interaction with natural elements; ephemeral and site-specific. |

Performance Art Today: A Constant Evolution

Performance art hasn't stopped evolving, not for a second. The intense, politically charged atmosphere of the 60s and 70s gave way to an art form that continues to push boundaries, incorporating digital media, extended durations (think Marina Abramović’s The Artist Is Present), and increasingly interactive elements. It might happen in a gallery, on a city street, or even online. This boundary-pushing spirit also manifests in immersive theatre, where audience members become participants in unfolding narratives or experiences, drawing heavily on performance art’s emphasis on direct, unrepeatable engagement.

Digital & New Media Performance

The rise of digital performance art and the use of online platforms, including social media, have created new venues and audiences, especially in a post-pandemic world, further blurring the lines between physical and virtual presence. It's fascinating to see how contemporary artists utilize platforms like Instagram and TikTok as stages for fleeting, yet impactful, interventions—from ephemeral visual statements and interactive stories to fostering community through shared online experiences. Concepts like "virtual embodiment," where artists create and perform through digital avatars, or "augmented reality (AR)" performances that overlay digital information onto physical spaces, are expanding what's possible. Even virtual reality (VR) is emerging as a powerful new medium, allowing artists to create entirely new, interactive, and spatially complex performative environments. This technological integration doesn't abandon the core principles of performance art but rather expands its potential for direct engagement and ephemeral expression, fostering a democratization of performance art by allowing wider access to creators and audiences globally. Beyond purely digital realms, the performative aspects of bio-art (working with living organisms or biological processes) and eco-art (addressing environmental issues through art, often involving public actions or interventions) are also expanding the medium's scope and relevance.

Documentation and Institutionalization

And crucially, because performance art is ephemeral, its documentation – through photography, video, written accounts, and archives – becomes vital. This documentation is often the only way many people experience these powerful, fleeting works, shaping our understanding of their legacy. Yet, this mediated experience can never fully replicate the raw, unrepeatable energy and direct presence of a live performance, creating a fascinating paradox at its heart. The ethical considerations around documenting sensitive works are immense. Questions of consent (from both artist and audience/participants), privacy, the potential for misinterpretation or exploitation when works are recontextualized, and how to faithfully capture the essence of a potentially distressing live act without sanitizing it while still preserving its historical significance, are constant challenges. The challenge for artists and archivists is how to capture the essence of something designed to disappear and how institutions grapple with acquiring, preserving, and exhibiting such intangible forms.

As performance art has matured, it has also seen a degree of institutionalization, with major museums and galleries acquiring performance works (often through their documentation or 'scores') and establishing dedicated performance programs. This shift has brought new visibility and academic study, but it also creates a fascinating tension: can a radical, ephemeral art form truly thrive within formal structures without losing its critical edge and anti-establishment roots? This question continues to shape its future, posing a challenge for institutions on how to acquire, preserve, and exhibit these unique, often intangible works. Many contemporary artists also utilize performance art festivals, such as Performa in New York or the Venice Performance Art Week, as vital platforms for experimentation and showcasing their work to a broader, engaged audience. It's a dynamic, ever-unfolding narrative, never truly static, mirroring my own artistic journey, a story always in progress, much like the one documented on my timeline.

But Why Should You Care? (Or, My Own Small Performances)

Having explored the vast landscape of performance art's history, you might be wondering how this all connects to us, to art that hangs on a wall, or even to your own life. So, we’ve journeyed through chaos and confrontation, introspection and societal critique. Perhaps you're thinking, 'This all sounds a bit… intense for me.' And that’s okay! I get it; the very idea of performance art can feel a bit like being asked to willingly step into a slightly uncomfortable social situation, like when I'm trying to explain my latest abstract series at a gallery opening, hoping it somehow performs its meaning. But I believe engaging with it, even just learning about its history, can profoundly expand your understanding of what art can be and why artists choose such a challenging medium. It offers a fresh perspective, perhaps even helping you to see the deliberate choices and inherent process within my own abstract paintings, connecting them to a broader artistic dialogue about presence and action, much like The Ultimate Guide to Abstract Art Movements might reveal new depths.

For example, imagine a painting from my art for sale collection. While it's a static object, the act of its creation – the spontaneous gestures, the decision to layer specific colors, the quiet, focused energy I pour into each brushstroke – is its own kind of performance, a silent, durational act played out in the studio. Just as a performance artist uses their body and time, I use my brushstrokes and colors to sculpt moments of intense focus and emotional resonance. The final canvas is merely the enduring trace of that live, internal performance. My intent, much like a performance artist, is to create an experience, albeit a silent one, that resonates emotionally and conceptually. Performance art challenges you to think beyond the frame, beyond the canvas. It invites you to consider the artist’s intent, their vulnerability, and the shared moment between creator and observer. It’s a reminder that art can be a dialogue, a question, an experience, rather than just an object to admire from a distance. The intent behind performance art is often not to entertain in a conventional sense, but to provoke thought, challenge perceptions, question societal norms, or create a profound, unrepeatable experience. Across its history, it has been a powerful tool for activism and protest, giving voice to marginalized communities and challenging injustices. Consider a moment in your everyday life: perhaps a protest march, a spontaneous street musician, or even an unexpectedly moving interaction with a stranger. These unscripted, direct, and emotionally resonant moments share a kinship with performance art, revealing the 'performance' in the everyday, waiting to be noticed. And if it makes you question your own perceptions, or see the 'performance' in your everyday life, then it’s done its job. What unexpected 'performances' are you overlooking in your daily existence?

Ultimately, every brushstroke I make, every color I choose, is a small performance of my own inner world. It’s a silent dialogue, an offering. And just like a great performance, I hope it resonates long after the moment of creation has passed.

Frequently Asked Questions About Performance Art

Here are some common questions I hear about this intriguing art form, and my attempts to untangle them:

- What's the difference between performance art and theatre? While both involve live action, theatre usually follows a script with characters and a narrative, aiming to tell a fictional story for entertainment through illusion. Performance art is often more abstract, conceptual, and focused on the artist's actions, a specific idea, or the ephemeral experience itself, rather than conventional storytelling. It prioritizes direct experience over theatrical illusion and often involves a spectrum of audience participation, from passive witnessing to active co-creation.

- Is performance art always controversial? Not always, but it often pushes boundaries, challenges norms, or addresses uncomfortable truths, which can lead to controversy. A common misconception is that its sole aim is to shock, but its purpose is frequently to provoke thought, question societal structures, or elicit a strong emotional response, rather than simply to entertain or please. This inherent drive to challenge means it can often stir strong reactions, especially when tied to activism or protest.

- Can you 'buy' performance art? It's tricky, as the live event is ephemeral. You can't acquire the performance itself. However, collectors often acquire its documentation (photos, videos, scripts, props, artist's notes), which becomes the tangible artifact. Sometimes, an artist might be commissioned to re-perform a piece, or a performance score – a set of instructions or a concept for a performance – can be sold and even licensed for re-enactment by others, making the idea itself a purchasable and replicable element. The artist's rights and the conditions of licensing for future performances are key considerations in its market.

- What are the ethical considerations in performance art? The extreme nature of some works, particularly in Body Art, raises questions about artist safety, audience consent, and the portrayal of pain or vulnerability. Moreover, the documentation of these works presents its own profound ethical challenges. Key considerations include consent (from both artist and participants/audience), privacy, the potential for misinterpretation or exploitation when works are recontextualized, and how to faithfully capture the essence of a potentially distressing live act without sanitizing it while still preserving its historical significance, are constant challenges for artists and archivists.

- Who are some famous performance artists? Some highly influential figures include Marina Abramović, Chris Burden, Yoko Ono, Allan Kaprow, Joseph Beuys, Carolee Schneemann, Valie Export, Vito Acconci, and the Gutai group. Each brought a unique vision and profound impact to the medium.

- How has technology impacted performance art? Technology has profoundly expanded its possibilities, from enabling complex multimedia installations and interactive elements to facilitating digital performance art, VR/AR experiences, and reaching global audiences through online platforms like social media. It allows for new forms of interaction, documentation, and artistic expression, blurring the lines between virtual and physical presence while opening up new avenues for engaging with its ephemeral nature and promoting a democratization of the art form, as well as influencing emerging fields like bio-art and eco-art.

- What is the audience's role in performance art? The audience's role is often far more active than in traditional art forms, existing on a spectrum. They are not merely spectators but can be passive witnesses, direct interactors, or even active collaborators. Their presence, reactions, and engagement are frequently integral to the work, shaping its meaning and impact in the moment. This direct interaction, and its varying degrees, is a cornerstone of many performance art pieces.

- What is the primary intent behind performance art? The primary intent is often to challenge, question, and provoke. Artists use performance to confront social issues, explore identity, test physical and mental limits, or simply invite a deeper, more direct engagement with an idea or experience. It’s about the immediacy of the moment and the conceptual power of action, rather than creating a lasting physical object. This intent frequently involves activism, social commentary, and a powerful desire to directly engage with the urgent issues of its time.

- Why is documentation of performance art so crucial? Because performance art is inherently ephemeral – a live, temporary event – documentation (through photos, videos, written accounts) becomes the primary way its legacy is preserved, studied, and experienced by a wider audience beyond the immediate moment. It acts as the tangible artifact of an intangible event, allowing for reflection, historical record, and continued critical discourse, ensuring its ideas persist even if the live act cannot be re-experienced.

The Unwritten Script (A Closing Thought)

Performance art, in its essence, is a relentless inquiry into what art is and can be. From the anti-art provocations of Dada to the visceral actions of Gutai, the social sculptures of Beuys, the feminist assertions of the 70s, and the digital experimentations of today, it has consistently served as a mirror reflecting societal shifts and an engine for artistic innovation. It’s a powerful testament to human creativity’s boundless capacity for reinvention, for constantly discovering new ways to articulate the inexpressible, often reflecting my own quiet struggles and breakthroughs in the studio. The story of performance art is still being written, piece by piece, action for action.

It reminds me of the vibrant, ever-changing exhibitions you can explore at my museum in Den Bosch, always offering something new to ponder. So next time you encounter something that makes you pause, that makes you think 'Is this art?', perhaps that's the greatest performance of all. The one that wakes something up inside you, much like the moment a new idea for a painting sparks to life, urging you to create. Remember, the true spirit of performance art, and indeed all art, resides not just in the grand gestures but in these moments of awakened perception, inviting you to see the world as a stage and your own actions as creative acts. And that, I think, is a beautiful thing. Perhaps even your life is an unfolding, vibrant performance, waiting to be fully embraced – go out and experience it, or better yet, create it.