What is Johannes Vermeer Known For? The Ultimate Guide

Unlock the quiet genius of Johannes Vermeer! Explore his mastery of light, intimate domestic scenes, and the timeless beauty of 'Girl with a Pearl Earring' and 'The Milkmaid' in this deeply personal guide. Discover what makes Vermeer a true legend of the Dutch Golden Age.

Johannes Vermeer: The Quiet Echoes of Genius – The Ultimate Guide to What He's Known For

Oh, hello there! You’ve found it – the ultimate, most comprehensive guide to Johannes Vermeer, crafted by an artist who's spent countless hours lost in his canvases. Seriously, what is it about this guy? As an artist myself, deeply inspired by his profound ability to capture those fleeting, intimate moments, I’ve spent countless hours contemplating the subtle, almost magical threads woven into his works. It’s a genuine honor to share my insights and delve into the quiet brilliance of one of the Dutch Golden Age's most enigmatic figures. This article isn't just a guide; it's your comprehensive journey into what truly makes Vermeer, well, Vermeer. Prepare to discover why his legacy continues to whisper so powerfully across centuries, compelling us to pause and truly see. We're here to answer the exact question you're likely pondering: What is Johannes Vermeer known for? And trust me, the answer is far more complex and captivating than you might expect.

Vermeer. Just the name itself feels like a soft, intimate whisper in the often-boisterous grand gallery of art history, doesn't it? When people ask me, "What is Vermeer known for?", I often find myself pausing. It’s not a question with a quick, bullet-point answer, because his legacy, his very essence, is so much more profound than a simple list of achievements. He’s known for a feeling, a captured moment, a particular way of seeing the world – a vision so unique, so deeply observed, that once you’ve experienced it, you never quite forget, placing him among the most important artists in history. It’s like discovering a secret garden in the middle of a bustling city; suddenly, everything else seems to quiet down around it. This profound sense of quietude and introspection truly sets him apart, even from his illustrious contemporaries like Rembrandt or Frans Hals. My own journey as an artist has often led me back to Vermeer's quietude, seeking that same depth of emotion in my own abstract forms, trying to distill that same sense of serene observation, and perhaps even to achieve that same timelessness, that sense of a moment suspended in amber. He is, above all, known for:

- His unparalleled mastery of light, transforming everyday scenes into luminous, almost spiritual encounters.

- His intimate interior scenes that capture moments of profound human experience, making us silent witnesses to private lives.

- His limited yet luminous body of work – a testament to a relentless pursuit of perfection, valuing quality over quantity.

- And, of course, iconic masterpieces such as 'Girl with a Pearl Earring' and 'The Milkmaid', which have captivated generations and transcended the art world.

Now, I know what you might be thinking: "But what about Rembrandt?" And I get it – who doesn't marvel at the sheer dynamism and drama of a Rembrandt's 'Night Watch'? But Vermeer, oh, Vermeer offers a different kind of magic entirely. It’s not about grand narratives, biblical epics, or dramatic portraiture. It’s about the soul of a moment, the poetry of the everyday, rendered with an almost spiritual quietude. While both artists are undisputed titans of the Dutch Golden Age, their approaches offer a fascinating contrast, almost like two sides of the same artistic coin. You might think, "Surely, Rembrandt is the more important artist?" Not so fast. To really drive home the distinction, and why both are equally compelling in their own right, let's look at them side-by-side, acknowledging that while Rembrandt's drama screams, Vermeer's intimacy whispers, and both leave an indelible mark on the soul – just in very different ways:

Feature | Johannes Vermeer | Rembrandt van Rijn |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Intimate genre scenes, domestic life, quiet introspection | Portraits, biblical/historical narratives, dramatic action |

| Light Usage | Soft, diffused, atmospheric; creates mood and texture | Chiaroscuro; dramatic contrasts, spotlighting figures |

| Brushwork | Smooth, meticulous, almost invisible | Expressive, visible brushstrokes, impasto |

| Composition | Carefully balanced, often geometric, serene | Dynamic, often diagonal, bustling |

| Output | Limited (approx. 35 paintings) | Prolific (hundreds of paintings, prints, drawings) |

| Subject Matter | Primarily women in interiors, cityscapes | Wide range: self-portraits, group portraits, allegories |

| Legacy | Master of domestic interiors, light; rediscovered in 19th C. | Master of psychological depth, prolific; consistently celebrated |

| Viewer Experience | Invites quiet contemplation, personal connection | Engages with dramatic narrative, emotional intensity |

| Artistic Philosophy | Focus on inner world, universal human experience in small moments | Explores external drama, grand narratives, human condition |

| Legacy Perception | Rediscovered master, cherished for unique vision, profound quietude | Consistently celebrated, master of psychological depth & drama |

So, let’s pull up a chair, dim the lights just a touch, and really dive into what makes Vermeer, well, Vermeer. We'll start by setting the stage, understanding the vibrant, bustling world that ironically shaped his quiet genius – a contradiction I find endlessly fascinating. It’s a bit like finding a perfectly still pond amidst a bustling marketplace, isn’t it?

Unpacking the Vermeer Enigma: Why Does He Still Captivate Us?

Before we dive into the specifics, let's just take a moment to consider the sheer enduring power of Vermeer's work. What is it about these quiet, often small, paintings that continues to draw us in, centuries after their creation? I think it boils down to a few key elements that resonate deeply, regardless of era:

- Universal Human Experience: His intimate scenes, while set in 17th-century Holland, touch upon emotions and moments that are timeless – contemplation, anticipation, domesticity, love, and quiet dignity. We see ourselves in these moments, don't we?

- Mastery of Observation: Vermeer teaches us how to see. He invites us to slow down and notice the intricate details, the subtle play of light, the texture of fabric, the glint on a pearl. It's a masterclass in mindful observation.

- Intrigue and Mystery: So much remains unknown about Vermeer's life and the exact narratives within his paintings. This enigma fuels our imagination, inviting us to project our own stories onto his canvases, making each viewing a personal journey.

- Technical Brilliance: From his revolutionary use of light to his precise compositions and vibrant pigments, his technical prowess is simply astounding. Artists and art lovers alike can spend hours dissecting the sheer skill on display.

It’s this potent combination of relatable humanity, profound observation, subtle mystery, and unparalleled technique that ensures Vermeer's quiet echoes continue to resound so powerfully in our collective consciousness. He’s not just an artist; he's a gateway to seeing the world a little more deeply, a little more beautifully. And honestly, isn't that what we all hope for from art? To shift our perspective, just a little? A painter friend of mine once described it as a slow burn – the more you look, the more you find, and that's a feeling I always try to infuse into my own creations, often with abstract art that invites lingering contemplation.

A Glimpse into the Dutch Golden Age: Vermeer's World

To truly appreciate Johannes Vermeer, we need to step back and understand the vibrant, complex era he inhabited: the Dutch Golden Age (roughly the 17th century). This wasn't just a period of artistic flourishing; it was a time of unprecedented economic prosperity, scientific advancement, and a burgeoning merchant class in the Netherlands. Think global trade routes stretching to the East Indies, daring explorations, scientific revolutions (like Christiaan Huygens's advancements in optics and pendulum clocks!), and a society that was, in many ways, surprisingly modern and remarkably tolerant, especially compared to its European neighbors. Delft, his hometown, was a particularly dynamic hub, known for its iconic ceramics (Delftware), thriving breweries, military arsenal, and a vibrant intellectual community, attracting thinkers and artisans alike. All of these elements indirectly contributed to the rich cultural milieu Vermeer operated within, creating a unique tension between the outward bustle and his inward focus. It’s fascinating how such a hub of commerce, innovation, and intellectual curiosity could foster an artist so dedicated to stillness, almost as if he was creating a sanctuary within the bustling world. I often reflect on how much a city's unique pulse can shape an artist's vision, much like the vibrant energy of Den Bosch influences its own local art scene, proving that environment is a powerful, if subtle, muse. It’s a testament to the idea that sometimes, the most profound peace can be found within the greatest clamor.

The Protestant Work Ethic and its Artistic Reflection

This era was also shaped by the pervasive influence of Calvinism and the Protestant work ethic, which emphasized diligence, frugality, and a focus on domestic virtues. While Vermeer himself converted to Catholicism later in life, the broader cultural values of his time undoubtedly influenced the art market and the themes that resonated with his burgher patrons. His tranquil domestic scenes, often depicting women engaged in modest, virtuous tasks like reading, lacemaking, or pouring milk, subtly reflect these societal ideals. They are not grand religious narratives, but rather celebrations of quiet piety, industry, and the simple dignity found within the home. It’s a fascinating interplay, isn't it, between the spiritual undercurrents of a society and the seemingly secular art it produces? It makes you wonder how much our own contemporary values are subtly mirrored in the art we create and consume today.

Unlike the Catholic countries where the Church or aristocracy were the primary patrons, in the predominantly Protestant Dutch Republic, a remarkably different market for art emerged: the wealthy burghers and ambitious merchants. These weren't your traditional aristocratic patrons; they were entrepreneurs, traders, and civic leaders who desired art that reflected their daily lives, their values, and their homes – not necessarily grand religious allegories or historical epics. This seismic shift created fertile ground for new and flourishing genres like still life, landscape, portraiture, and most importantly for Vermeer, genre painting – intimate scenes of everyday life. This democratisation of art, where a broad middle-class became the new patrons, allowed for an unprecedented focus on domestic life and everyday moments, a stark departure from the grand religious and mythological narratives favoured elsewhere in Europe. It’s a fascinating contrast, isn't it, how a society built on bustling commerce, naval power, and global trade could give rise to art so profoundly tranquil, almost as if capturing the serene moments amidst the worldly clamor? It makes me think about how even in our own busy, digitally connected lives, we still crave those moments of stillness, those quiet pauses. For a broader look at the period, you might want to explore articles about the Dutch Golden Age, or indeed, the wider art capitals of the world that thrived during different eras. This unique patron-artist relationship fostered a different kind of artistic vision, one that celebrated the domestic and the personal, aligning perfectly with Vermeer’s quiet genius.

Guilds and Apprenticeship: Paving the Artist's Way

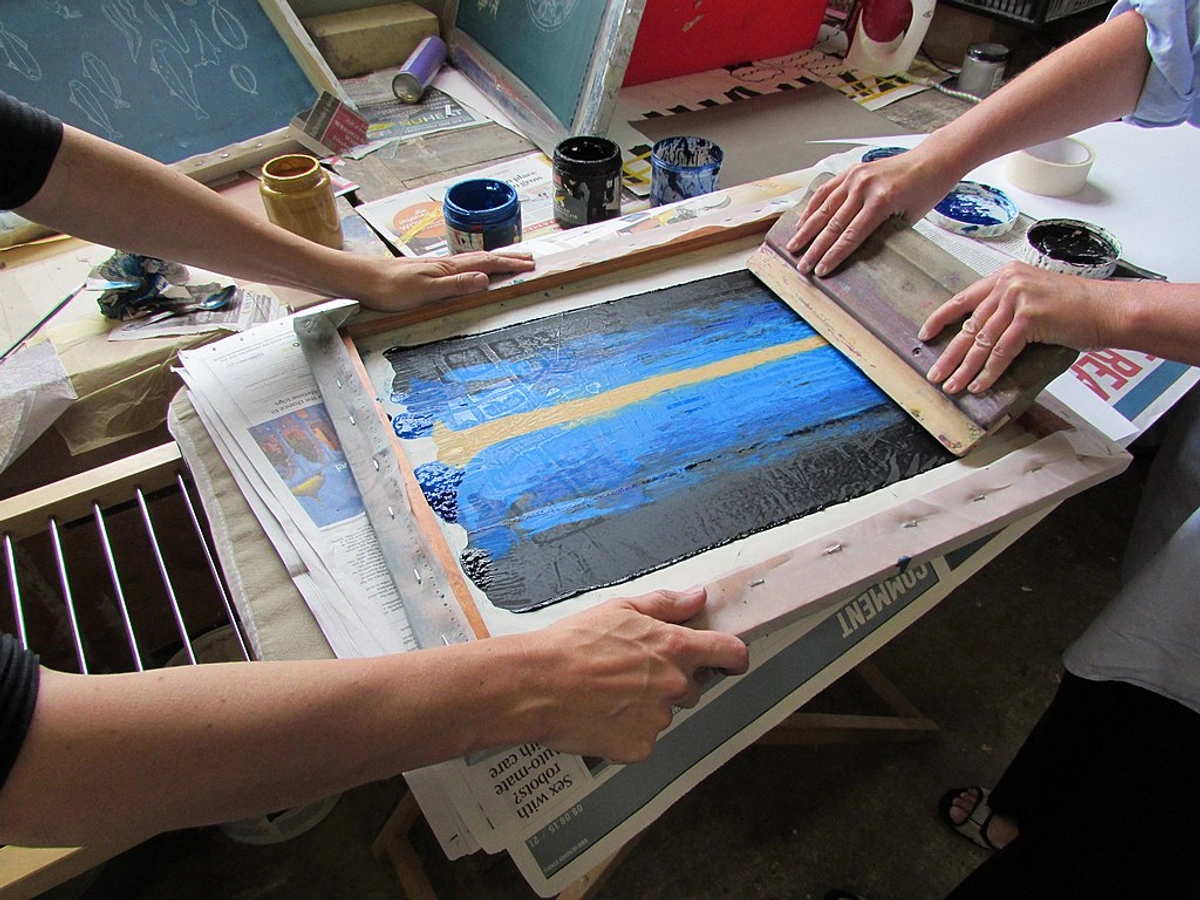

Becoming a master painter in 17th-century Delft wasn't just about talent; it was a formal process rooted in the Guild of Saint Luke. This professional organization, much like a modern-day trade union, regulated the artistic profession, setting standards for training, quality, and market access. Vermeer's membership, attained in 1653, was a crucial rite of passage, officially granting him the right to sell his works and take on apprentices. The Guild also provided a network for artists, ensuring a degree of professional standing and protecting their craft, from regulating the number of apprentices to ensuring a minimum quality standard. While specifics of his formal training are scarce – a common mystery with many Old Masters – he likely apprenticed with a local master for several years. A strong candidate is Carel Fabritius, a brilliant student of Rembrandt, who tragically died young in the devastating Delft gunpowder explosion of 1654. This potential mentorship, even if brief, would have exposed Vermeer to innovative approaches to light and perspective, fundamentally shaping his early artistic development. It’s a reminder that even solitary geniuses operate within a vibrant ecosystem of mentorship and craft, learning the ropes and refining their skills under experienced eyes. It’s a bit like how even the most innovative contemporary artists still draw from the traditions and techniques passed down through generations, building on a shared foundation of knowledge and skill. Perhaps this early influence from Fabritius, who was known for his mastery of perspective and illusionistic effects, sowed the seeds for Vermeer's own groundbreaking explorations in rendering space and light. It's a tantalizing thought, isn't it, to imagine the direct artistic lineage shaping such a distinctive vision?

The Unrivaled Master of Light: A Silent Symphony

If there’s one thing that absolutely screams "Vermeer!" to me, it's his almost supernatural, almost magical, ability to paint light. It's a skill that reminds me of the deep dives into the subject you can find in resources like Definitive Guide to Understanding Light in Art. I mean, we all see light, right? It falls on objects, it creates shadows, it reveals form. But Vermeer? He didn't just paint light; he painted its texture, its weight, its temperature. He famously achieved this with pointillé – the subtle application of tiny, luminous dots of paint that catch and reflect light, creating a shimmering, almost tactile quality on surfaces like pearls, satin, or even bread crusts. It’s a technique that breathes life into mundane objects, making them glow with an inner radiance, almost like tiny, individual pixels of light. He painted the way it dances across a patterned rug, the way it softens the edge of a woman's cheek, the way it almost shimmers on a pearl. It’s this almost tactile rendering of light that makes his works feel so incredibly present, as if the air itself holds a specific humidity or coolness. Honestly, as an artist, painting light is one of the hardest things to master – it's ephemeral, constantly changing. But Vermeer captures it with such precision and poetry, making it feel utterly timeless. I find myself trying to capture this same subtle interplay of light and shadow in my own abstract compositions, to give them that same sense of atmospheric presence and enduring glow. It's a profound study in how light itself can become the subject. And for a deeper dive into this essential artistic element, you might find a lot to unpack in the Definitive Guide to Understanding Light in Art – it’s a resource I often revisit!

The Allure of 'Pointillé': Tiny Dots, Big Impact

Let's talk a moment more about pointillé. This isn't just a technical flourish; it's a fundamental aspect of how Vermeer achieved that shimmering, almost vibrating quality in his highlights. Imagine tiny, jewel-like beads of pure light, painstakingly applied, that catch the eye and make a surface seem to breathe. It’s a visual trick that predates Impressionism by centuries, creating an optical blend that adds an incredible sense of realism and vitality. Whether it's the glint on a pearl, the texture of a bread crust, or the folds of satin, pointillé imbues these elements with a tangible presence, almost inviting you to reach out and touch the canvas. It's a subtle yet utterly captivating technique that demonstrates his profound understanding of how our eyes perceive light and form, and something I often consider when trying to give my own abstract works a sense of internal luminescence.

The Science of Light: Precision and Illusion

It’s easy to get lost in the poetic beauty of Vermeer’s light, but there’s a subtle science at play too. He understood optics, perhaps instinctively, perhaps through tools, allowing him to render reflections, refractions, and the subtle ways light diffuses across different materials. This wasn’t just about making things look real; it was about creating an illusion of presence, making the viewer feel like they could step right into his carefully constructed worlds. The precise fall of light on a tiled floor, the delicate reflection in a windowpane, or the way a curtain filters the outside world – these are all meticulously observed phenomena that contribute to the immersive quality of his work, revealing a mind deeply attuned to the physics of sight. He didn't just paint what he saw; he painted how light makes us see.

Chiaroscuro vs. Vermeer's Soft Light: A Different Drama

While his contemporary, Rembrandt, was a master of chiaroscuro – dramatic contrasts between light and dark, often spotlighting figures with intense illumination – Vermeer pursued a different kind of magic. His light is rarely harsh; instead, it's soft, diffused, and often enters from an unseen window, gently enveloping his subjects and filling the space with a palpable atmosphere. It's less about high drama and more about quiet revelation. This subtle, even democratic, distribution of light contributes to the serene and contemplative mood of his paintings, allowing every object in the scene to exist harmoniously within the illuminated space. It's a testament to his unique vision, showing that intensity doesn't always need theatricality; sometimes, the softest whisper can be the most profound.

More Than Illumination: Light as Emotion

It’s not just about scientific accuracy for him, though he was certainly a keen observer. For Vermeer, light is a character in itself – arguably the most important one. It imbues his domestic scenes with a sense of quietude, introspection, and sometimes, a palpable mystery. Think of how a shaft of light from a hidden window can transform a simple act, like pouring milk, into something monumental, as seen so powerfully in 'The Milkmaid'. It elevates the mundane, giving it a profound, almost spiritual glow. Or consider the way light catches the enigmatic gaze of the 'Girl with a Pearl Earring', making her feel intensely alive and present, yet utterly unknowable. This is the kind of profound connection that light can forge, and it's a constant fascination for me, even in the abstract realm. It’s like a silent protagonist, guiding our eyes and shaping our emotional response, almost a divine presence within the everyday.

This meticulous attention to light is perhaps his most enduring signature. It's why his works feel so incredibly real, yet simultaneously ethereal. It's like he's showing us the world, but with a veil of quiet wonder draped over it. This profound understanding of light’s ability to evoke emotion is a cornerstone of his lasting appeal, making his canvases feel less like paintings and more like portals to another time.

The Camera Obscura Connection

While not definitively proven, a compelling and widely debated theory suggests Vermeer may have extensively used a camera obscura – essentially a darkened room or box with a small hole or lens that projects an inverted image onto a surface. Think of it as a very early, rudimentary projector; no batteries, just light and optics! This optical device could have significantly aided him in achieving his incredibly precise perspective, those subtly diffused highlights (the discs of confusion, as they're sometimes called, referring to the out-of-focus circles of light characteristic of lenses), and the uncanny, almost photographic quality some of his images possess. Proponents of the "Hockney-Falco thesis," for instance, have extensively argued that Vermeer and other Old Masters likely employed such optical aids, believing it wasn't 'cheating,' but a sophisticated tool, enabling a deeper exploration of visual reality, blurring the lines between art and early science. Imagine the artist, hunched over his canvas, tracing the ephemeral image projected before him, capturing reality with an almost scientific precision while infusing it with poetic depth. It makes me wonder what he could have done with today's technology, or how these techniques connect to broader art movements and the evolving relationship between technology and artistic creation. It's a testament to his innovative spirit, regardless of the tools he employed. And honestly, isn't it always fascinating when art and science collide? This intersection of technology and artistic vision is something we still grapple with today, constantly redefining the boundaries of creativity, much like the evolving landscape of abstract art movements.

Beyond the Lens: Vermeer's Subjectivity

Even if he used optical devices, it's crucial to understand that Vermeer was no mere copyist. The camera obscura might have provided a structural framework, a kind of visual blueprint, but the soul of his paintings – the profound emotional resonance, the carefully chosen symbolism, and the breathtaking color harmonies – these were purely the product of his artistic genius and subjective vision. He selected what to highlight, interpreted the light, and infused the scenes with meaning. It's the difference between a photograph and a poem; one captures reality, the other reveals its essence and evokes a feeling that lingers long after you’ve looked away. He wasn't just observing; he was feeling and interpreting, which is where the true art lies.

The Hallmarks of Vermeer's Art: A Quick Overview

To truly distill what sets Vermeer apart, what makes him so uniquely compelling, here are some key characteristics that define his unmistakable style – the very essence of "Vermeer-ness":

Characteristic | Description | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Mastery of Light | Precise rendering of light's texture, weight, and temperature; subtle gradients | Creates unparalleled realism, atmosphere, and emotional depth |

| Intimate Interiors | Focus on domestic scenes, often featuring a solitary female figure | Offers a glimpse into 17th-century Dutch private life; evokes quiet contemplation |

| Limited Color Palette | Strategic use of expensive pigments (e.g., ultramarine) with vibrant effect | Achieves luminosity, richness, and harmonious color schemes |

| Meticulous Detail | Painstaking attention to textures, fabrics, and everyday objects | Enhances realism; invites close observation; reveals subtle symbolism |

| Geometric Composition | Carefully structured, often using linear perspective and vanishing points | Creates a sense of order, depth, and spatial harmony |

| Psychological Depth | Figures often caught in moments of introspection; subtle emotional cues | Engages the viewer; creates a sense of mystery and narrative |

| Small Output | Approximately 35 known paintings | Highlights dedication to perfection and scarcity value |

| Technological Aids | Likely employed a camera obscura for perspective and light effects (theory) | Contributed to the distinctive realism and optical qualities |

| Fewer Figures | Often depicts one or two figures, usually women, in quiet moments | Amplifies intimacy and psychological depth; focuses attention |

| Psychological Nuance | Subtle expressions and gestures hint at inner lives and contemplative states | Engages viewer in narrative; fosters empathy and mystery |

| Domestic Symbolism | Everyday objects carry deeper meanings (maps, instruments, letters) | Enriches narrative; adds layers of moral or romantic interpretation |

| Sense of Stillness | Figures and scenes are often suspended in moments of profound quietude | Creates timeless quality; invites deep contemplation; fosters intimacy |

| Precise Composition | Often uses vanishing points, geometric structures, and controlled depth of field | Creates a sense of order, harmony, and immersive space |

| Luminous Pigments | Favored expensive, vibrant pigments like ultramarine and lead-tin yellow | Achieves intense, jewel-like colors and radiant effects |

The Man Behind the Canvas: Vermeer's Life and Delft Roots

Johannes Vermeer (1632-1675) spent his entire life, a remarkably quiet life for such a celebrated artist, in the bustling, prosperous city of Delft, a hub of trade, science, and art in the 17th-century Netherlands. His father, Reijnier Janszoon Vermeer, was a weaver, art dealer, and innkeeper, which likely exposed young Johannes to the art world and its commercial aspects from an early age. Imagine growing up surrounded by paintings, conversations about art, and the daily ebb and flow of merchants and travelers. It's a childhood ripe for observation, wouldn't you say? This unique environment, blending business with aesthetics, surely fostered Vermeer’s meticulous attention to domestic scenes and material textures, allowing him to absorb the visual language of his time while cultivating his own introspective vision.

In 1653, a pivotal year, he became a master in the Guild of Saint Luke, the local painters' guild – an essential and formalized step for any professional artist of the time, granting him the right to sell his work. He also married Catharina Bolnes, who came from a wealthier, more prominent Catholic family. This marriage led to Vermeer's conversion to Catholicism – a significant personal, social, and even artistic decision in the predominantly Protestant Dutch Republic. This shift in faith, while not overtly dictating his subject matter, may have subtly influenced the deeper moral and spiritual undertones found in some of his later works, particularly those with vanitas elements or themes of judgment. Their union resulted in a large, bustling household; they would eventually have 15 children, though only 11 survived to adulthood. Imagine trying to maintain profound quietude in a house with eleven children! Yet, this busy domestic life, often seen as the very backdrop to his work, was, in my opinion, intrinsic to it. His subjects, predominantly women in domestic settings – perhaps even his own wife or daughters – reflect the intimate world he knew so profoundly, a world he meticulously distilled into moments of profound quiet and universal human experience. His incredibly meticulous, slow working pace, producing only two or three paintings a year, suggests an artist not driven by commercial volume, but by an intense, almost obsessive, pursuit of artistic perfection – a lesson in quality over quantity that still resonates powerfully today. It's a reminder that sometimes, the true masterpieces emerge from slow, dedicated engagement, impervious to the pressures of mass production, and often from the very fabric of one's personal life.

Despite his artistic dedication, Vermeer's financial situation was often precarious. He supplemented his income through his family’s inherited art dealing business and by running an inn, 'Mechelen', which also served as a gallery for his own works and those he traded. The Franco-Dutch War of 1672, notoriously known as the "Rampjaar" (Disaster Year), dealt a severe blow to the Dutch economy and, consequently, the art market. With patrons unable to afford new commissions, Vermeer accumulated significant debt, tragically dying in 1675 at the age of 43, leaving his wife and children in dire financial straits, and a legacy of quiet artistic struggle. The scarcity of his output today thus not only highlights his perfectionism but also underscores the profound personal and economic challenges he navigated, making each surviving masterpiece even more precious, a testament to art enduring against all odds. It’s a powerful reminder that immediate commercial success doesn’t always align with enduring artistic impact – much like the contemporary art pieces you can buy today that are destined for future admiration, or understanding how to value art through art appraisals. This precarious existence, I think, makes his serene domestic worlds all the more poignant; perhaps they were the very sanctuaries he sought to create in a life filled with external pressures.

Intimate Interior Scenes: Worlds Within Walls

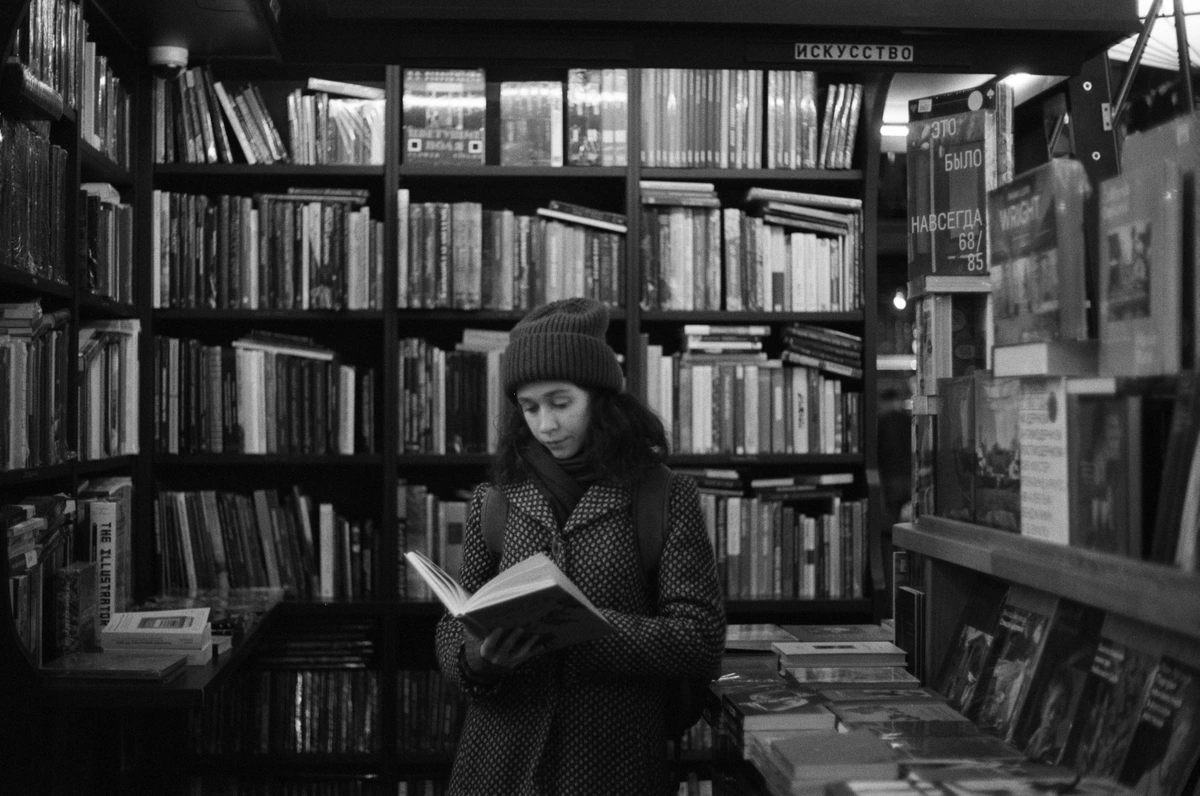

Vermeer is renowned for his genre paintings, specifically those intimate, tranquil interior scenes that offer us a precious, almost voyeuristic glimpse into 17th-century Dutch domestic life. And no, this isn't just about painting pretty rooms or charming vignettes. Oh no. These are meticulously constructed narratives, often centered around a solitary figure, usually a woman (or sometimes a domestic servant, as in 'The Milkmaid'), engaged in seemingly mundane yet profoundly evocative everyday activities: reading a letter, playing a musical instrument, pouring milk, or perhaps, simply contemplating. They are not merely pretty pictures; they are profound psychological studies, inviting us to ponder the inner lives, unspoken thoughts, and hidden emotions of his subjects. It's as if he captures a breath held, a thought just forming, a silent drama unfolding before our eyes, allowing us to project our own narratives onto these quiet moments.

The Interior as a Microcosm

For Vermeer, the domestic interior wasn't just a setting; it was a microcosm of the world, a stage where human drama, subtle emotions, and moral allegories unfolded. The confined space amplified the intimacy, drawing the viewer into the psychological world of the sitter. Every object, every ray of light, every gesture was carefully placed to contribute to this profound sense of internal narrative. It’s a powerful lesson in how limiting your scope can, paradoxically, expand your depth. It reminds me of setting up a still life in my own studio – the arrangement isn't just aesthetic, it's about creating a narrative, a moment frozen in time. In this sense, his interiors are less about depicting a specific reality and more about crafting a psychological space.

I often imagine what it must have been like in his Delft studio. Was it as quiet as his paintings suggest? He had a large family, after all! But in his art, he somehow distills the chaos of life into moments of profound stillness, creating a sanctuary. This focus on the private, the unobserved, is a hallmark of his genius. He invites you in, not as a voyeur, but as a silent observer, allowing you to share in the quiet dignity of his subjects, making us question their thoughts and feelings. Many of these figures are women from the burgeoning Dutch middle class, engaged in cultured pursuits like reading, writing, or playing music, reflecting the values and aspirations of his patrons. It’s a deliberate choice, I think, to show us a world of quiet contemplation, a sanctuary from the bustling commercial life outside. He often uses recurring objects within these scenes – specific chairs, windows, tapestries, and even particular types of pottery – almost like props in a meticulously staged play, further enhancing the sense of a controlled, deeply considered reality. It's not just a room; it's his room, filled with his observations, imbued with his unique artistic spirit.

Beyond the Surface: Symbolism in Vermeer's Domestic Worlds

Vermeer's paintings, while seemingly straightforward depictions of daily life, are often incredibly rich with subtle, layered symbolism. He was a master of embedding profound meaning within the mundane, turning everyday objects into silent commentators on human experience, virtue, moral choices, or even the complexities of love and longing. It’s like finding hidden messages in plain sight, isn't it? This is where his genius truly shines, inviting us to look closer, to truly interpret what we see, to become active participants in deciphering his visual poetry. It reminds me of how a seemingly simple color in an abstract painting can hold a universe of emotion, depending on how you choose to see it, or how a single brushstroke can evoke an entire feeling. It’s this intellectual engagement, this puzzle-solving, that elevates his work beyond mere domestic scenes, transforming them into quiet allegories. It's a profound reminder that sometimes, a single hue, a specific object, or even the placement of a figure, can transform an entire narrative. The way he manipulates these elements, sometimes with explicit allusions, sometimes with subtle suggestions, truly demonstrates his depth as a storyteller, using paint as his language. For anyone fascinated by the deeper meanings behind artistic choices, the interplay of these elements is a constant source of wonder, much like understanding how artists use color to evoke specific emotions and narratives.

Common symbolic elements often subtly woven into the fabric of his domestic scenes, inviting deeper contemplation and analysis, include:

- Maps and Globes: Frequently appearing in his backgrounds, these signify exploration, knowledge, and the burgeoning Dutch global trade. They can also allude to the transient nature of life or intellectual pursuits, often referencing the Netherlands' powerful maritime status and its intellectual curiosity. The presence of a map of the Low Countries in 'The Art of Painting', for example, is a direct nod to national identity and historical significance, placing his intimate scenes within a much grander, global context.

- Musical Instruments: Lutes, virginals, and guitars often suggest harmony, love, or seduction. Music was a popular pastime in Dutch homes, and its inclusion often adds a layer of intellectual and emotional depth, hinting at the inner lives and cultured pursuits of his subjects. The quiet presence of a lute or virginal suggests a melody unheard, a private symphony unfolding within the stillness. In 'The Concert', for instance, the shared act of music-making becomes a metaphor for intimacy and connection, and perhaps even for the fleeting nature of sound itself.

- Letters: Women reading or writing letters are a recurring motif, hinting at personal narratives, longing, or secret communications, adding a layer of psychological intrigue to his figures. The unseen contents of these letters become a powerful narrative device, inviting the viewer to speculate on the emotions and stories contained within, as seen in 'Woman in Blue Reading a Letter' or 'A Lady Writing a Letter'. These literary props transform a simple genre scene into a moment of profound human connection or internal reflection.

- Scales: In works like 'Woman Holding a Balance', scales can symbolize justice, judgment, or the careful weighing of worldly possessions against spiritual values, a subtle reminder of the fleeting nature of earthly gains.

- Windows and Doors: Often partially obscured or framing the light source, windows can symbolize connection to the outside world, spiritual illumination, or even a barrier. Doors, whether open or closed, can suggest entry, exit, or concealed spaces, subtly guiding the viewer's eye or hinting at untold stories beyond the frame.

- Paintings-within-paintings: Vermeer often included depictions of other artworks on the walls of his painted rooms (e.g., the map in 'The Art of Painting' and the Last Judgment in 'Woman Holding a Balance'). These can serve as allegories, moralizing elements, or even commentaries on art itself, adding layers of intellectual depth and self-awareness to his compositions.

- Delftware: The distinctive blue and white ceramics, often seen in his works, serve as both a local touch and a symbol of Dutch economic prowess and global trade. They root his scenes firmly in the prosperous reality of his time, reminding us of the everyday luxury and cultural identity of 17th-century Holland.

- Books and Letters: These often signify literacy, education, and the intellectual life of the sitter, as well as being vehicles for emotional narratives, elevating the domestic sphere to one of intellectual and emotional richness.

- Curtains and Draping: Often pulled back to reveal the scene, these can act as theatrical devices, drawing the viewer in, or symbolically represent the unveiling of truth or intimacy. This visual 'peeking' effect heightens the sense of a private moment being shared, almost like a stage curtain being drawn back just for you, emphasizing the preciousness and vulnerability of the scene. They often frame the composition, creating a sense of a carefully constructed window into another world, enhancing the sense of voyeurism and quiet observation.

Understanding these subtle clues transforms his tranquil scenes into deeper narratives, revealing a complex interplay between the visible world and hidden meanings. It's a reminder that sometimes, the quietest stories are the most profound, much like how a single symbol in my own abstract work can shift the entire meaning of a piece. Vermeer, it seems, always had a little more to say than met the eye at first glance.

The Limited but Luminous Oeuvre: Quality Over Quantity

Here’s a fact that always blows people's minds, even mine: Johannes Vermeer only produced around 35 known paintings. Just 35! In an era where artists churned out works like a bustling factory, Vermeer was the absolute antithesis. This incredibly small, precious body of work speaks volumes about his profound dedication to perfection, his painstaking process, and, let's be honest, the specific commercial realities of his life. Unlike many prolific contemporaries who relied on a broader market, Vermeer had a more limited, but deeply loyal, circle of patrons. His most important patron was probably Pieter van Ruijven, a wealthy Delft citizen, who purchased a significant number of his works, acting almost as an exclusive collector. This consistent patronage, while perhaps limiting his broader market exposure, crucially allowed Vermeer the freedom to work slowly and meticulously, prioritizing artistic excellence over rapid production. It highlights a common truth for artists throughout history: a dedicated patron can be the crucible for unparalleled creativity, providing the stability needed to pursue true mastery without the incessant pressure of commercial output. Imagine having that luxury today, to only create when absolute perfection calls!

However, this wasn't a path to immense wealth. Despite his talent, Vermeer's financial situation was often precarious, especially given his large family. He supplemented his income through his family's art dealing business and by running an inn. The Franco-Dutch War of 1672, often called the "Rampjaar" (Disaster Year), severely impacted the Dutch economy and art market, proving particularly devastating for him. With patrons unable to afford new commissions, Vermeer fell into significant debt, ultimately dying in 1675 at the age of 43, leaving his wife and children in dire financial straits. The scarcity of his output today only underscores the profound personal and economic challenges he faced, making each surviving masterpiece even more precious, almost like a rare gem that survived a storm. This also reminds me that true artistic impact isn't always tied to immediate commercial success, but often to an enduring quality that transcends its own time – much like the contemporary art pieces you can buy today that are destined for future admiration, or understanding how to value art through art appraisals. He wasn't a prolific artist, and that scarcity only adds to the mystique and value of each piece. It's a profound statement on artistic integrity over commercial gain, a quiet rebellion against the commercial pressures of his age.

The Economics of Perfection: Why So Few?

This scarcity wasn't just about a slow working pace; it was a complex interplay of personal artistic philosophy, market demand, and economic reality. Unlike large workshops that catered to a broad clientele, Vermeer's approach was intensely personal and deliberate. Each painting was a significant investment of time, rare pigments, and meticulous effort. The limited number of dedicated patrons, though financially supportive, meant less pressure to churn out quantity. It's a fascinating economic model, one that valued depth and artistic integrity over commercial output, and it's a testament to the artist's unwavering vision, even in the face of financial hardship. This dedication to crafting a perfect piece, rather than many good ones, is a hallmark of true mastery. It's a tough lesson, but sometimes saying 'no' to more means saying 'yes' to excellence. This deliberate scarcity, coupled with his unparalleled skill, is precisely why each surviving Vermeer is considered such a treasure, fetching astronomical sums at auction and drawing crowds to museums worldwide. The sheer reverence commanded by each canvas speaks volumes about the power of singular vision.

It makes me think about my own creative process. Sometimes, it’s tempting to just produce, produce, produce. But then I look at Vermeer, and it’s a powerful reminder that true impact isn't always measured by volume. Sometimes, it's about the singular, perfect expression, painstakingly brought to life.

Iconic Masterpieces: Windows to Another Time

Iconic Masterpieces: Windows to Another Time

Among his limited collection, a few pieces stand out as monumental achievements, instantly recognizable and endlessly fascinating. But beyond the immediate superstars, there are others that offer equally profound insights into his genius, each a meticulous window into his unique vision and unparalleled mastery. It’s a bit like discovering a hidden track on an album you already love; suddenly, the whole experience deepens, revealing new layers of brilliance. I remember feeling this exact thrill when I first encountered some of his lesser-known, yet equally masterful, works, realizing that every single painting he created is a precious artifact of quiet contemplation. Let's delve into some of these iconic masterpieces, and a few others that deserve just as much contemplation, for they each hold a universe of silent beauty. These are the paintings that define his legacy, each a carefully constructed world awaiting our quiet observation.

The Art of Painting (c. 1666-1668)

The Art of Painting (c. 1666-1668)

Often considered Vermeer's most complex and arguably his most personal and ambitious work, 'The Art of Painting' (c. 1666-1668) isn't just a genre scene; it's a profound, almost allegorical declaration on art itself. It depicts an artist, his back to us (a deliberate and ingenious device to make us feel like we're peeking over his shoulder), diligently painting a model dressed as Clio, the Muse of History. The rich tapestry, the intricate chandelier, and the large map of the Netherlands on the wall all speak to the intellectual and cultural aspirations of the Dutch Golden Age, and perhaps, the artist's own place within it. What I find truly remarkable is the way Vermeer uses light to draw our eye, not just to the figures, but to the very act of creation, to the sacred process itself. It's like he's inviting us into his inner sanctum, showing us not just what he paints, but why he paints, and what he considers the true essence of his craft. It's a deeply personal, yet universally resonant, exploration of artistic endeavor, creativity, and the enduring power of history and representation. Its complex composition, with the artist's back to the viewer, draws us into the creative process itself, making us participants rather than mere observers. It’s almost as if he’s inviting us to consider the very nature of art and inspiration, and his own profound contribution to it – a true self-portrait of his artistic philosophy, a masterclass in meta-commentary. This painting is often seen as a subtle yet powerful declaration of his artistic ideals, placing the pursuit of art within a historical and allegorical context, elevating his own quiet practice to something profound and enduring.

Woman Holding a Balance (c. 1662-1663)

Woman Holding a Balance (c. 1662-1663)

In 'Woman Holding a Balance' (c. 1662-1663), Vermeer presents a scene that is both exquisitely tranquil and deeply symbolic. A young woman, seemingly pregnant, stands before a table, delicately holding an empty balance in her hand, while behind her, a powerful painting of the Last Judgment hangs prominently on the wall. This juxtaposition is absolutely key, isn't it? She's weighing nothing in her physical hands, yet the profound context suggests she's contemplating the delicate balance between fleeting worldly possessions and eternal spiritual rectitude, perhaps even her own soul. The light, as always, is central, streaming in from an unseen window to illuminate her serene face, the shimmering pearls, and the glittering jewels on the table, inviting us to consider our own priorities and the ultimate reckoning. It's a quiet, introspective meditation on judgment, morality, and the choices we make – a subtle yet profound vanitas painting, gently reminding us of the fleeting nature of earthly treasures and the eternal weight of spiritual values. The exquisite rendering of light on the pearls and the balance itself emphasizes this delicate interplay, making the mundane transcendent and deeply meaningful. It truly makes you pause and think about what you are balancing in your own life. It's a masterclass in quiet contemplation. The subtle glow around the balance and the woman's pensive expression invites reflection on themes of temperance and the ephemeral nature of worldly possessions – a truly profound visual sermon without a single spoken word.

The Little Street (c. 1657-1658)

The Little Street (c. 1657-1658)

Another of Vermeer's rare, almost unheard-of, excursions outside the intimate interior is 'The Little Street' (c. 1657-1658). This delightful cityscape offers a detailed and charming glimpse into 17th-century Delft, a true anomaly in his oeuvre focused almost exclusively on indoor scenes. It's a masterclass in architectural realism, with brickwork, crumbling plaster, and even tiny shutters rendered with astonishing precision, almost like a loving portrait of his hometown's quiet corners. I always find myself drawn to the quiet domesticity of the figures – children playing in a doorway, a woman sewing – which subtly echo the themes of his interior scenes, but within an external setting. It's not just a street; it's a living, breathing fragment of his hometown, imbued with that characteristic Vermeer tranquility and an unparalleled sense of place, almost as if the very air of Delft is captured. The meticulous detail in the brickwork and crumbling plaster makes it feel incredibly real, a quiet ode to the architectural beauty of 17th-century Delft. It’s almost as if you can hear the faint sounds of daily life echoing from its quiet corners, a profound quietude that only Vermeer could achieve in an urban setting. It’s a testament to his versatility, showing he could find the same profound stillness outdoors as he did indoors, a quiet counterpoint to his indoor dramas. This rare outdoor scene offers valuable insight into Vermeer's broader observational skills and his ability to infuse even the most public spaces with his characteristic sense of quietude and detailed observation.

Woman in Blue Reading a Letter (c. 1663-1664)

Woman in Blue Reading a Letter (c. 1663-1664)

In 'Woman in Blue Reading a Letter' (c. 1663-1664), Vermeer once again masterfully captures a private, contemplative moment, almost like a stolen glance. A young woman, dressed in a striking blue jacket (likely made with his prized ultramarine pigment), stands utterly absorbed in reading a letter, the soft, diffused light from an unseen window illuminating her face and the crisp paper in her hands. The profound stillness of the scene, the subtle folds of her garment, and the gentle shadows create an atmosphere of profound introspection and quiet anticipation. The content of the letter remains a mystery, forever sealed within the canvas, inviting us, the viewers, to fill in the narrative gaps – a common and captivating technique Vermeer employed, amplifying the emotional weight. It speaks to the universal human experience of anticipation, longing, or reflection triggered by written correspondence, making a simple, silent act incredibly evocative and deeply personal. It’s a testament to his ability to convey deep emotion through subtle cues, the power of the unseen, and exquisite control of light and color, truly making the mundane monumental. It's a timeless portrayal of private thought. The striking blue of her jacket, likely painted with his beloved ultramarine pigment, further draws our attention to her, making her the undeniable focal point of this quiet, unfolding drama. It’s a delicate balance of color, light, and unspoken narrative that truly embodies the 'Vermeer-ness' we so admire.

View of Delft (c. 1660-1661)

View of Delft (c. 1660-1661)

One of only two known landscapes by Vermeer – a true rarity and a testament to his versatility – 'View of Delft' (c. 1660-1661) is an absolute marvel of urban topography and atmospheric light. Standing before it, I always feel a pang of nostalgia for a place I've never been, a time long past, almost as if I'm breathing the very air of 17th-century Delft. It’s a meticulously observed, almost photographic (again, the camera obscura theory comes to mind!), rendering of his hometown, bathed in a soft, ethereal glow that feels utterly unique to that specific moment. The interplay of sunlight on the buildings, the shimmering reflections in the water, the intricate details of the port and its tiny, bustling people – it all creates a sense of tranquil grandeur and profound stillness. It's not just a city view; it's a deeply personal portrait of Delft, alive with its own unique light and rhythm, a timeless capture of a specific place at a specific moment. It’s a landscape that invites contemplation, revealing new details each time you look, almost a 'portrait' of his beloved city. The meticulous rendering of the brickwork, the reflection of the clouds in the water, and the tiny figures going about their day all contribute to an astonishing sense of lived reality, a captured moment of urban tranquility that feels utterly timeless. This painting, a clear exception to his indoor focus, showcases his expansive observational gifts.

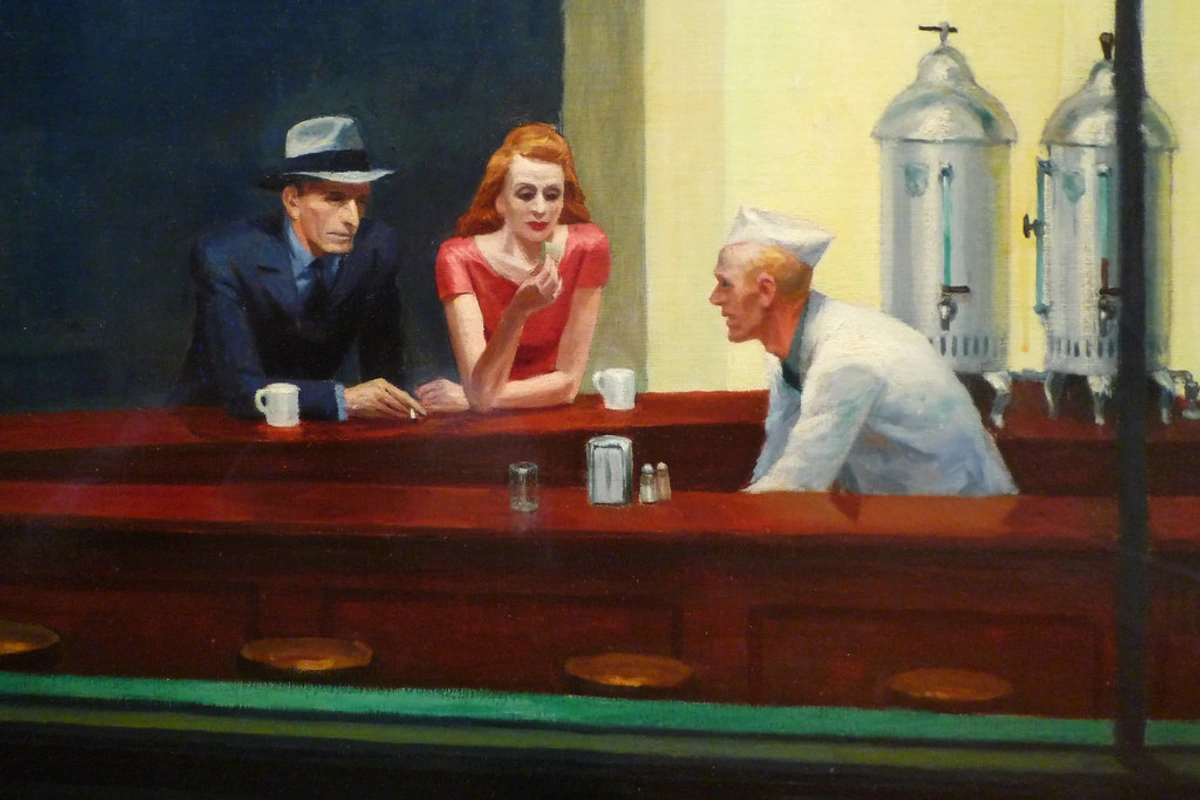

The Girl with a Pearl Earring (c. 1665)

The Girl with a Pearl Earring (c. 1665)

Ah, 'The Girl with a Pearl Earring' (c. 1665). The undeniable "Mona Lisa of the North." If you know one Vermeer, it’s almost certainly this one, the iconic image that has captured imaginations for centuries. What makes it so utterly captivating, so impossibly magnetic? Is it her enigmatic gaze, looking directly at you, almost challenging you to understand her thoughts, her unspoken secrets? Is it the vibrant, almost living, play of light on that impossibly large, luminous pearl, seemingly glowing from within? Or the striking contrast of her vivid blue and yellow turban against the deep, featureless background, which pushes her forward into our space, making her intensely present?

I remember seeing it for the first time at the Mauritshuis in The Hague (and seriously, you really should go, if you ever get the chance). It felt like she was breathing, that her lips were moist with a whispered secret, that a thought was just about to form behind those eyes. It’s a masterful study in emotion, light, and understated drama, an absolute triumph of psychological depth conveyed through subtle artistic choices. It draws you in, holds you, and makes you wonder about the story behind those eyes, about the identity of this mysterious young woman. It's a profound, almost intimate, connection he creates between subject and viewer, transcending time and space. It's not just a painting; it's an encounter, a silent conversation across centuries, a meeting of souls. That enigmatic expression, that direct gaze – it’s a stroke of genius that continues to captivate and mystify, making you feel as if you’re the only one she’s ever truly looked at, sharing a secret only with you. The vibrant blue and yellow turban, the simple dark background that isolates her, and that impossibly luminous pearl all contribute to her timeless, universal appeal, making her a "tronie" – a study of a face or character, not necessarily a specific portrait – that transcends mere portraiture to become an icon of quiet mystery, a symbol of beauty and the unknowable. It's a testament to how much depth, how much human essence, can be conveyed with a singular, perfectly rendered moment, a profound whisper in the grand chorus of art history. The fact that her identity remains unknown only adds to her allure, turning her into a universal figure, a mirror for our own reflections. It's a perfect example of his ability to distill emotion into its purest form, using minimal elements to achieve maximum psychological impact. This painting, in my opinion, is the ultimate representation of his ability to make you feel something profound, without ever quite knowing why.

The Milkmaid (c. 1658-1660)

The Milkmaid (c. 1658-1660)

Then there's 'The Milkmaid' (c. 1658-1660). This painting, for me, is an absolute testament to the beauty, dignity, and quiet heroism of everyday labor. It's not glamorous; it's a humble scene, a woman, sleeves rolled up, carefully, almost reverently, pouring milk into an earthenware pot. But again, and this is where Vermeer’s genius truly shines, he elevates this simple, domestic act to something extraordinary through his unparalleled handling of light and texture, transforming the mundane into the monumental.

Look at the bread on the table – you can almost feel its crust, the coarse texture contrasting with the smooth earthenware jug and the glistening milk. The basket on the wall, the tiny nails, the light catching the Delftware tiles at the bottom, even the subtle cracks in the plaster – every detail is rendered with exquisite, almost obsessive, care, each surface speaking its own language. It’s a masterclass in rendering different surfaces, a symphony of textures, and the way the light from the window illuminates the scene, bringing an almost sacred warmth and tangible presence to an otherwise humble domestic task. It's a profound celebration of quiet competence, dignity in labor, and the exquisite beauty found in the everyday, reminding us to seek grace in the simplest of actions. It always makes me appreciate the simple, honest moments in my own life, and the quiet heroism of daily routines, finding profound meaning in the overlooked. This isn't just paint on canvas; it's a window into a moment, perfectly preserved, brimming with life, a profound tribute to the unsung grace of domestic work and the enduring power of human endeavor. It shows us that even the most ordinary moments hold extraordinary beauty, if only we take the time to truly see them, much like finding the sublime in the mundane. It’s a quiet masterpiece that celebrates the everyday, dignifying domestic labor and transforming a simple act into a meditation on presence and light. Every element, from the humble bread to the glowing milk, becomes a subject of profound beauty.

Woman with a Pearl Necklace (c. 1662-1665)

'Woman with a Pearl Necklace' (c. 1662-1665) is another stunning example of Vermeer's mastery of light and profound domestic intimacy. Here, a young woman stands before a mirror, a moment of quiet vanity or anticipation, delicately adjusting her pearl necklace, bathed in the soft, diffused light from an unseen window. The apparent simplicity of the scene utterly belies its profound psychological depth and emotional resonance. We're privy to a private, fleeting moment of adornment and self-reflection, rendered with an almost ethereal glow, as if time itself has paused. The light, meticulously captured as it reflects off the pearls and the lustrous folds of her silken jacket, creates a luminous, almost palpable atmosphere that encapsulates a moment of quiet grace, perhaps even a hint of melancholy or contemplation. It makes me wonder about the subtle narratives unfolding within these seemingly mundane acts, about the woman's inner world – a feeling I often strive to evoke in my own art, finding the universal in the personal. This painting, like many others, pulls you into a private space, making you a silent witness to an unfolding internal world, a silent soliloquy in paint. The interplay of the woman and her reflection in the mirror adds another layer of introspection, questioning perception and self-awareness. It's moments like these that truly make me wonder about the inner lives of his subjects, a quiet narrative playing out in front of our very eyes.

Key Themes in Vermeer's Work: Unveiling the Layers

Key Themes in Vermeer's Work: Unveiling the Layers

While Vermeer is celebrated for his technical mastery, his paintings also resonate with profound themes that elevate them beyond mere depictions of domestic life. He wasn't just showing us what was happening, but inviting us to ponder why it mattered. This underlying intellectual and emotional depth is what truly makes his work timeless, speaking to universal human experiences despite their specific 17th-century setting.

- Domesticity and Interiority: His focus on intimate interior scenes wasn't just about capturing daily life; it was an exploration of the private world, the quiet moments of reflection and engagement within the home, turning these enclosed spaces into stages for internal drama.

- Light as a Spiritual Element: As we discussed, light isn't just illumination; it's a character, often imbued with a spiritual quality that elevates the mundane to the monumental. It suggests divine presence or inner enlightenment, almost a silent blessing on the domestic scene.

- Morality and Virtue: Many of his works subtly explore themes of virtue, prudence, and the transient nature of worldly pleasures. The careful arrangement of objects and the contemplative expressions of his subjects often hint at deeper moral considerations, inviting the viewer to engage in self-reflection.

- The Act of Observation: Vermeer's meticulous realism challenges the viewer to truly observe, to see the beauty and complexity in what might otherwise be overlooked. He teaches us how to look, and in doing so, how to appreciate the quiet drama of the everyday.

- Leisure and Quiet Engagement: His figures are often engaged in activities like reading, playing music, or writing – acts of leisure and intellectual or emotional engagement that speak to the values of his time and the burgeoning culture of domestic refinement. It suggests a society that valued quiet contemplation as much as outward achievement, a counterpoint to the bustling commercial world outside.

- Harmony and Balance: Beyond the visual composition, there's a profound sense of emotional and philosophical balance in his works, often contrasting the material with the spiritual, or the fleeting with the eternal. It's a delicate dance between opposing forces, beautifully rendered.

- The Role of Women: His consistent depiction of women, often in moments of quiet dignity and intellectual engagement, offers valuable insight into the lives and aspirations of women in 17th-century Dutch society, portraying them with respect and depth, elevating them beyond mere decorative figures.

- Silence and Stillness: Perhaps the most defining theme, Vermeer's art is a profound ode to silence. His scenes are devoid of overt drama, instead celebrating the quietude of domestic life and inviting viewers into a space of calm contemplation, a sanctuary from the bustling world. The almost tangible silence in his works encourages us to slow down and truly observe, offering a rare moment of peace in our often-noisy lives.

- Music and Harmony: Musical instruments often appear in his paintings, not just as props but as symbols of harmony, love, or even seduction. Music was a popular pastime in Dutch homes, and its inclusion often adds a layer of intellectual and emotional depth, hinting at the inner lives and cultured pursuits of his subjects. The quiet presence of a lute or virginal suggests a melody unheard, a private symphony unfolding within the stillness, adding an auditory dimension to his visual quietude.

- The Power of Stillness: Beyond a mere compositional choice, the pervasive stillness in Vermeer’s works can be interpreted as a reflection of a desire for order and calm in a rapidly changing, bustling world. These moments of suspended animation offer viewers a refuge, a chance to slow down and truly absorb the beauty of the present, almost as if time itself has paused within the frame. It’s an almost meditative quality that I, as an artist, continually strive for in my own work.

These themes are not overtly declared but woven into the fabric of his compositions, requiring us to be active participants in deciphering their quiet power. It's an invitation to pause, observe, and engage with the layers of meaning, much like deciphering the intricate interplay of colors and forms in a complex abstract piece. His work, in essence, becomes a silent dialogue between the artist and the viewer, spanning centuries. These deep, underlying currents are what transform his seemingly simple genre scenes into profound philosophical statements, inviting endless interpretation and appreciation.

A Peek into Vermeer's Studio: Techniques and Theories

A Peek into Vermeer's Studio: Techniques and Theories

While Vermeer's exact working methods remain somewhat mysterious, art historians and enthusiasts have long speculated about his techniques. One prominent theory, one that always gets me thinking about innovation, suggests he may have used a camera obscura, an optical device that projects an image onto a surface. Think of it as a very early, rudimentary projector – no batteries, just light and optics! This would have aided him in achieving his incredibly precise perspective, subtle gradations of light and shadow, and that slightly diffused, almost photographic quality some of his images possess. Proponents of the "Hockney-Falco thesis," for instance, have extensively argued that Vermeer and other Old Masters likely employed such optical aids. It wasn't "cheating," as some might argue, but a sophisticated tool, enabling a deeper exploration of visual reality. It makes me wonder what he could have done with today's technology, or how these techniques connect to broader art movements! But beyond the optical aids, it's his masterful application of paint that truly sets him apart, revealing a profound understanding of his materials. This blend of scientific curiosity and artistic intuition is, for me, one of the most compelling aspects of his genius – a constant push to see and represent reality in new and captivating ways.

Vermeer's Color Palette and Application

Vermeer's Color Palette and Application

Beyond the optical devices, his use of pigments and his approach to color were absolutely remarkable, bordering on extravagant. He was known to use incredibly expensive colors like ultramarine (derived from lapis lazuli, a semi-precious stone imported all the way from Afghanistan) liberally, almost lavishly. This wasn't just a stylistic choice; it would have been a significant financial investment, demonstrating an unwavering, almost audacious, commitment to achieving those incredibly vibrant, luminous effects that make his colors sing across centuries. He didn't shy away from these costly materials, using them to create those signature deep, rich blues that still hold their intensity centuries later, making his 'Woman in Blue' or the turbans of his 'Girls' truly glow. He also expertly employed lead-tin yellow (for those brilliant yellows), vermilion, and various earth pigments, all carefully ground and prepared to achieve maximum luminosity. It’s this audacious commitment to the highest quality materials, often at great personal expense, that speaks volumes about his artistic integrity. He wasn't cutting corners; he was striving for an intensity of color that would sing across centuries, a lesson in pure, unadulterated artistic vision.

Beyond these carefully selected pigments, his deliberate choices of color and their interplay are remarkable. He understood that placing certain colors next to each other could enhance their vibrancy, a lesson I constantly revisit in my own pursuit of dynamic color compositions. His application techniques included:

- Layering: Building up colors in thin, translucent layers to achieve depth and luminosity, creating a rich inner glow, almost like light shining through stained glass.

- Glazing: Applying thin, transparent layers of paint over dried opaque layers to modify color, deepen tones, and create shimmering, jewel-like effects, as if light is truly passing through the paint.

- Impasto: Though generally smooth, he occasionally used thicker, textured paint (impasto) for specific highlights, like the pearls or the glint on bread, to catch and reflect real light, adding a tactile dimension to the surface, making you almost want to reach out and touch it.

- Pointillé: As mentioned earlier, the use of small, distinct dots of light-reflecting paint to create sparkling, almost shimmering, textured surfaces that come alive when viewed from a distance, giving a unique 'flicker' to his highlights.

- Foreshortening: His masterful use of perspective, potentially aided by the camera obscura, allowed him to create convincing spatial depth, especially with figures or objects receding into the background, drawing the viewer into the scene with an almost magnetic pull.

- Optical Blending: Rather than mixing all colors on the palette, Vermeer often used small dots or strokes of pure color next to each other, allowing the viewer's eye to blend them from a distance. This technique, a precursor to Impressionism's pointillism, contributes to the luminous, vibrant quality of his surfaces.

- Scumbling: He would often apply a thin, opaque layer of lighter paint over a darker one, using a dry brush, creating a soft, broken texture that allowed some of the underlying color to show through. This added to the atmospheric quality and richness of his surfaces, particularly in depicting light-drenched walls, giving them a subtle, varied texture that feels almost breathable.

This sophisticated interplay of light, color, and technique is what makes peering into a Vermeer painting feel like a masterclass in visual perception. It's not just about the final image, but the painstaking, intelligent process behind every luminous detail. For further exploration on the power of color in art, I highly recommend checking out How Artists Use Color – it’s a constant source of inspiration for me!

He truly understood how light interacts with different surfaces, creating those mesmerizing textures we see in his work. This commitment to materials and painstaking application is something every artist, myself included, can learn from. It reminds us that sometimes the most profound effects are born from the most precise and deliberate choices, a balance between scientific observation and pure artistic intuition. It's this exquisite blend that makes his work endlessly fascinating, a testament to his dedication to the craft. It's a compelling argument, I think, for the idea that true genius isn't just about what you create, but how you create it – a marriage of vision, technique, and a relentless pursuit of perfection, even if it meant a life of struggle.

The Enduring Legacy: From Obscurity to Immortality

The Enduring Legacy: From Obscurity to Immortality

Vermeer’s influence, despite his limited output and relative obscurity during his lifetime, is immense. And yet, here’s the truly fascinating twist, almost a tragic irony: for nearly two centuries after his death, Johannes Vermeer was largely forgotten, vanishing from the mainstream of art history. His paintings were often misattributed, sometimes even to more famous, more commercially successful artists of the time like Gerard ter Borch or Gabriel Metsu. It’s almost unthinkable now, isn't it, that such quiet, profound genius could simply fade into the background, a silent echo in the grand, noisy gallery of art history, waiting patiently to be heard again?

It wasn't until the mid-19th century that Vermeer's star began its slow but undeniable ascent, resurrected from the dusty archives of obscurity. A passionate and tenacious French art critic, Théophile Thoré-Bürger, played a truly pivotal, almost heroic, role in his rediscovery. Driven by a deep, almost spiritual, appreciation for the anonymous master, Thoré-Bürger painstakingly researched and attributed dozens of paintings to Vermeer, embarking on extensive travels across Europe to locate and verify works that had been misattributed or simply languished, forgotten, in private collections. His seminal series of articles, published in the prestigious Gazette des Beaux-Arts in the 1860s, systematically cataloged Vermeer's known oeuvre and meticulously detailed his distinctive style, his unique "signature" of light and quietude. This dedicated, almost singular, scholarship single-handedly brought the artist's unique vision back into the public consciousness. This period of intense research and advocacy, often called the "Vermeer Revival," firmly re-established his rightful place as one of the most significant and celebrated artists of the Dutch Golden Age. It's a powerful reminder that art history is not static; it's a dynamic, evolving narrative, often reshaped by the discerning eyes and tireless dedication of later generations who are willing to look closer. Thank goodness for tireless art historians, right? Otherwise, we might still be missing out on this quiet genius. And this rediscovery, I think, makes his story all the more compelling – a quiet triumph against the currents of time, proving that genuine brilliance will, eventually, find its audience.

The Forgery Factor: A Dark Tribute to Value

The Forgery Factor: A Dark Tribute to Value

Before his rediscovery, and even after, Vermeer's limited output made him a prime target for forgers. Perhaps the most infamous case was Han van Meegeren in the 20th century, who, during World War II, created incredibly convincing "Vermeers" that fooled even the most seasoned experts for years. This dark chapter, though regrettable, ironically testifies to the enduring allure and perceived scarcity of genuine Vermeer works. It reminds us that even in the art world, there's a constant dance between authenticity and imitation, and that the immense value placed on scarcity often attracts unscrupulous talent. It’s a stark reminder of the challenges of authentication and the lengths some will go to replicate perceived genius, in a twisted tribute to the original master's impact, a macabre compliment indeed. The story of Van Meegeren, in particular, highlights the intense desire for more Vermeer – a testament to the insatiable hunger for his unique vision, even if it leads to deception. It's a fascinating, if unsettling, footnote to his legacy, demonstrating the profound cultural impact of his art.

Today, his legacy transcends the art world. His works have inspired novels like Tracy Chevalier's 'Girl with a Pearl Earring' and the subsequent film adaptation, bringing his enigmatic figures to a global audience. Filmmakers are captivated by his sense of light and composition, using his paintings as visual references. Artists, both traditional and contemporary, marvel at his technique and the profound humanity he captured. He reminds us that true genius can lie dormant for generations, only to be recognized when the world is finally ready to truly see it. It’s a powerful testament to art’s enduring power, waiting patiently for its moment in the spotlight. Understanding his place in the broader art timeline helps appreciate this journey. His ability to capture profound human emotion and the beauty of the ordinary in such a captivating way ensures his place as one of the most beloved and enigmatic artists of the Dutch Golden Age. Moreover, ongoing scientific analysis and conservation efforts continue to reveal new insights into his techniques and materials, ensuring his legacy continues to unfold. It’s like discovering new layers in an old song; the appreciation just deepens.

Vermeer's Influence on Later Artists and Pop Culture

Beyond art history circles, Vermeer's influence has permeated popular culture in remarkable ways. Tracy Chevalier's novel 'Girl with a Pearl Earring' (and the subsequent film adaptation starring Scarlett Johansson) brought his most iconic work to a global audience, sparking renewed interest in the artist's life and mysterious subjects. Filmmakers and photographers often draw inspiration from his masterful use of light and carefully balanced compositions, striving to achieve that same sense of quiet drama and atmospheric depth. His works are referenced in music, literature, and even contemporary art installations, a testament to their enduring visual power and psychological resonance. It’s truly fascinating to see how a 17th-century painter's vision continues to inspire and shape creative expression across diverse mediums today. He’s become a cultural touchstone, a symbol of enigmatic beauty and artistic perfection, proving that true genius transcends its original context to become a universal language.

His paintings remind us to slow down, to look closely, and to find the extraordinary in the everyday. That's a lesson I try to carry into my own art, and honestly, into my daily life. The way Vermeer finds complexity and emotion in the simplest of scenes profoundly influences my own approach to art, even when working with abstract forms and vibrant colors. It’s about distilling an essence, finding the light in unexpected places, and recognizing the profound in the everyday – a philosophy I aim to infuse into every brushstroke, and one that I often reflect upon when crafting my artist statement. There’s so much beauty hidden in plain sight, if only we take the time to truly see it. And if you're ever looking to bring a piece of that captured beauty into your own space, remember that the spirit of these masters lives on in contemporary art, often waiting for you to buy a piece that truly speaks to you, perhaps even something from a collection focusing on collecting emerging abstract art. It's art that whispers across the centuries, always inviting you closer.

Frequently Asked Questions About Johannes Vermeer

Frequently Asked Questions About Johannes Vermeer

Q1: How many paintings did Vermeer create?

A1: Johannes Vermeer is known to have created a relatively small body of work, with only about 35 paintings attributed to him today. This scarcity is a significant factor in their high value and mystique, making each surviving piece a true treasure. It's a testament to his meticulous approach and dedication to perfection, rather than mass production.

Q2: Why are Vermeer's paintings so rare?

A2: Several factors contribute to the rarity of Vermeer's paintings. He worked incredibly slowly and meticulously, often producing only two or three paintings a year – a truly painstaking process that prioritized quality over quantity. He also had a limited circle of patrons, primarily one wealthy individual, Pieter van Ruijven, which didn't necessitate high volume or chasing numerous commissions. Finally, the economic downturn caused by the Franco-Dutch War of 1672, known as the "Rampjaar" (Disaster Year), severely impacted the Dutch economy and art market, further limiting his output and financial stability in his later years. It’s a sad fact that even genius can be affected by the economy.

Q3: What are Vermeer's most famous paintings?

A3: His two most famous paintings are undoubtedly 'The Girl with a Pearl Earring' and 'The Milkmaid'. Other well-known works include 'The Art of Painting' (his profound allegorical work on art itself, almost a self-portrait of his artistic philosophy), 'View of Delft' (one of his two rare cityscapes, a loving portrait of his hometown), 'Woman Holding a Balance' (a subtle vanitas painting prompting reflection on life's priorities), 'The Lacemaker' (celebrated for its exquisite detail and focus on domestic industry), and 'Woman with a Pearl Necklace' (a tender moment of private contemplation). Each offers a unique glimpse into his mastery and distinctive style, inviting endless fascination.

Q4: Why is Vermeer's use of light so distinctive?

A4: Vermeer's distinctive use of light goes beyond mere illumination; he captures its texture, weight, and emotional quality. He meticulously renders how light interacts with different surfaces, creating a sense of realism, depth, and a unique, ethereal glow in his intimate scenes. This includes his subtle use of pointillé (tiny dots of light-reflecting paint that give surfaces a shimmering, almost vibrating quality, almost like optical pixels), and his masterful observation of how light transforms ordinary objects into something profound, imbuing them with a sense of quiet dignity or even spiritual presence. It's often described as a character in itself within his paintings, guiding the viewer's eye and shaping their emotional response.

Q5: Did Vermeer use a camera obscura?

A5: While not definitively proven, many art historians believe Vermeer likely used a camera obscura to assist in his compositions and achieve such precise perspective and subtle optical effects. This theory, notably supported by the Hockney-Falco thesis, is backed by certain visual characteristics in his paintings, such as unique depth of field and luminous qualities. It's a fascinating blend of art and early optical science, showing his innovative spirit and willingness to explore new tools for artistic expression.

Q6: What period of art history is Vermeer associated with?

A6: Johannes Vermeer is a key figure of the Dutch Golden Age (roughly the 17th century), a period of immense artistic, scientific, and economic prosperity in the Netherlands. His work falls within the broader Baroque period, though his intimate and tranquil style is quite distinct from the more dramatic and theatrical flair often associated with Italian or Flemish Baroque art. He offers a unique, introspective perspective within this grand era, truly standing apart with his quiet brilliance.