Venus of Willendorf: Unearthing Ancient Art & Its Meaning

Discover the Venus of Willendorf, an iconic Paleolithic figurine. Explore its symbolism, history, and enduring appeal as a primal echo of human creativity in this engaging, personal guide.

What is the Venus of Willendorf? Unearthing Humanity's Ancient Artistic Echoes

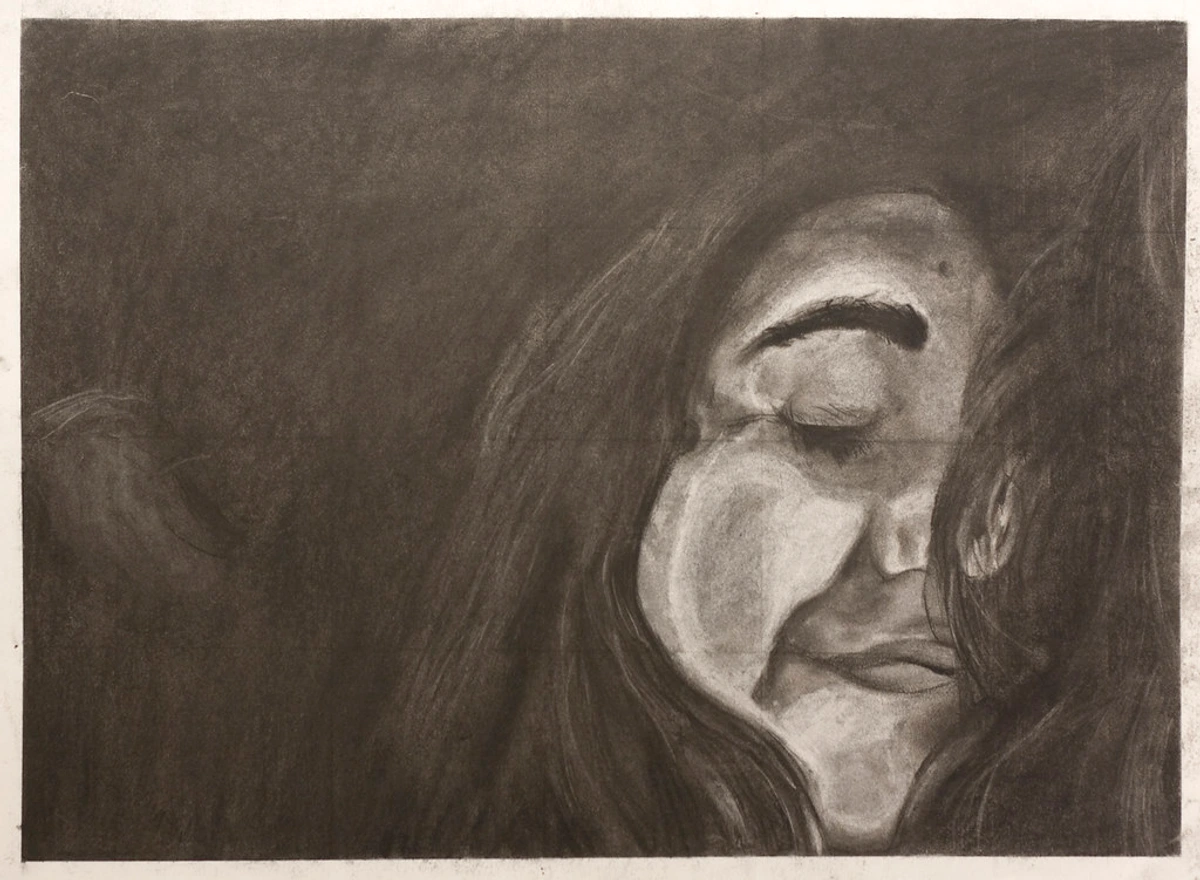

I sometimes find myself gazing at a blank canvas, wondering where this urge to create truly comes from. Is it a primal whisper from our distant past, an echo of humanity's earliest stirrings, or a sleek, modern construct born of our contemporary anxieties? When I ponder the very origins of art, my mind inevitably drifts to a tiny, unassuming figure that carries an immense story: the Venus of Willendorf. She's not a grand statue meant to dominate a public square, nor is she a meticulously rendered portrait demanding hyper-realism. Instead, she’s a pocket-sized enigma, a silent ambassador from a time before written history. For me, she encapsulates something profoundly human, something universal, about the artistic impulse. It’s a testament to our enduring need to create, to represent, and to imbue meaning into the material world, even when the 'why' remains shrouded in the mists of millennia. This isn't just an artifact; it's a foundational statement about what it means to be human and to make art, a truly monumental piece of history despite its humble size. What a thought, that something so small could carry such a weighty legacy!

A Tiny Titan: First Encounters with the Venus

Let's be honest, her fame belies her stature. If you were to hold the Venus of Willendorf in your hand – and oh, how I wish I could! – you'd find she's barely taller than a modern smartphone, measuring a humble 11.1 centimeters (about 4.4 inches). She's also remarkably light, weighing in at approximately 15 grams (about half an ounce), making her incredibly portable. Carved from oolitic limestone, a material not local to her discovery site in Austria, she presents a figure of striking, almost exaggerated, curves: pendulous breasts, wide hips, and a prominent belly. This choice of material, I think, is a silent clue, hinting at either extensive ancient trade networks or the nomadic wanderings of her creators. Imagine the journey that stone must have taken! Her arms are slender, almost delicate, resting on her chest, but it's her lower body that often grabs attention – specifically, the absence of discernible feet. This suggests she wasn't meant to stand unaided, perhaps implying she was held, carried, or pushed into soft earth during rituals or daily life. And her face... well, that's where things get really interesting, or rather, intentionally ambiguous. Instead of facial features, she has an elaborate pattern, often interpreted as braids, a woven cap, or perhaps even an abstract representation of hair, completely obscuring her face. It’s a deliberate choice, and one that forces us, as viewers, to look beyond individual identity and consider a deeper, more universal meaning. Even back then, artists were grappling with the power of omission and suggestion, understanding that what isn't explicitly stated can be the most potent part of a composition, much like how we explore these concepts in modern design in art. It's a foundational lesson for any artist, ancient or modern: sometimes, what you leave out speaks volumes more than what you put in.

Discovery and Historical Context

Discovered on August 7, 1908, by archaeologist Josef Szombathy near Willendorf, a small village in Lower Austria, during excavations of an Aurignacian-Gravettian settlement, her finding was a pivotal moment in understanding prehistoric art. She was unearthed from the archaeological Stratum IX, a loess layer that indicated continuous human occupation – a key detail often overlooked! This stratigraphic context allowed for precise dating, placing her firmly in the Upper Paleolithic period, specifically somewhere between 30,000 and 25,000 BCE. We're talking about the Gravettian culture here, a distinct phase of human history characterized by specific stone tools and portable art. That’s an almost incomprehensible span of time, isn't it? It makes you pause and think about the hands that shaped her, the mind that conceived her, and the world they inhabited – a world vastly different from our own, yet connected by this enduring creative spark. For me, it's humbling to consider how the fundamental human need to create has persisted through such dramatic shifts in environment and lifestyle.

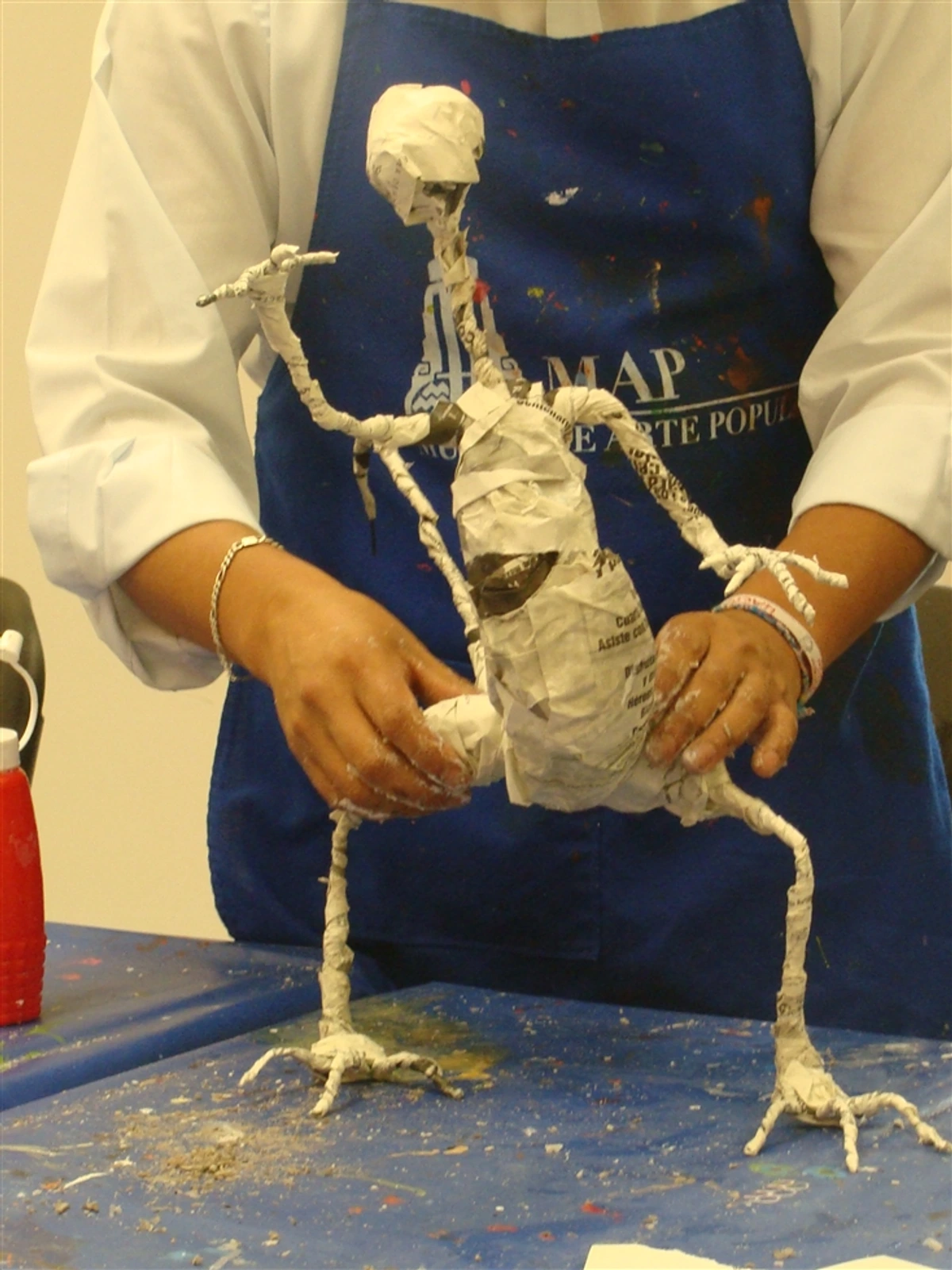

Craftsmanship from the Stone Age

Comparing Venuses: An Enduring Archetype

It's fascinating, isn't it, to see how the concept of 'Venus' – this powerful, feminine ideal – has evolved and been reinterpreted throughout art history? From the primal, abstract form of Willendorf to the classical grace of Canova's Venere Italica, or Botticelli's iconic 'Birth of Venus', the artistic impulse to represent fundamental aspects of womanhood and beauty persists. But while later 'Venuses' often focus on idealized physical beauty and mythological narratives, the Venus of Willendorf speaks to something far older, far more mysterious, and perhaps, more deeply rooted in the raw exigencies of survival. She embodies a different kind of beauty, one tied to the essence of life itself, rather than mere aesthetic perfection.

The Gravettian World: Climate, Culture, and Survival

To truly appreciate the Venus of Willendorf, I think we have to try and step into the shoes of her creators, however briefly. Imagine living in Europe between 30,000 and 25,000 BCE. This was a time dominated by the Last Glacial Maximum, meaning much of Europe was a vast, unforgiving tundra, punctuated by dense forests and icy rivers. Life was inherently challenging, dictated by the rhythm of seasons, the migration of herds, and the constant search for food and shelter. The people of the Gravettian culture were nomadic hunter-gatherers, highly skilled in crafting tools from stone, bone, and ivory. Their toolkit included sophisticated blades, burins, and projectiles, essential for processing game and raw materials. Their survival depended on an intimate understanding of their environment, collaborative hunting strategies for megafauna like mammoths, and a strong sense of community. Their artistic output – from impressive cave paintings to portable figurines like the Venus – wasn't just decoration; it was deeply intertwined with their worldview, their rituals, and their hopes for the future. For me, knowing this context makes the Venus not just an object, but a tangible link to a resilient, deeply spiritual people, who expressed profound ideas through their art even in the harshest conditions.

Decoding the Deep Past: What the Venus Tells Us

A Symbol of Life, or Something More?

The million-dollar question, and one that resonates deeply with anyone trying to understand the origins of art: what did she mean to her creators? The most pervasive theory, for good reason, is that the Venus is a fertility figure or a mother goddess. Her exaggerated features – the full breasts, wide hips, and prominent, often swollen, abdomen – strongly suggest a focus on reproduction and abundance. In a harsh, prehistoric world where life itself was tenuous and infant mortality high, celebrating the source of new life and the continuation of the clan would have been paramount. This isn't just about biological reproduction; it’s about the very survival of their society, embodying a profound hope and reverence for life-giving power. Many scholars point to the consistent depiction of these features across numerous Paleolithic figurines as strong evidence for this interpretation, suggesting a widespread cultural emphasis on these themes. Indeed, parallels can be drawn to similar fertility goddesses found in later ancient cultures, though direct connections remain speculative.

But here’s where it gets nuanced, and frankly, more fascinating to me as an artist. Beyond the fertility hypothesis, several other compelling interpretations exist. Some scholars propose she might be a form of self-portrait, perhaps made by a woman looking down at her own body, which would explain the exaggerated proportions and the lack of a face (you don't see your own face when looking down). This idea adds a deeply personal, intimate dimension to the artifact. Others suggest she was a spiritual object, a shamanistic totem, an amulet for protection during childbirth, or even a pedagogical tool used to teach younger generations about the female body and its reproductive capabilities. The absence of a discernible face isn't an oversight; it’s a deliberate choice that universalizes her. She isn't a specific woman; she is woman itself, or perhaps a representation of a collective ancestral mother or a goddess figure. It’s this ambiguity, this invitation to project our own interpretations, that keeps her so compelling. It reminds me a bit of how abstract art can evoke so many different emotions and meanings in viewers today – the power lies in what isn't explicitly stated. This intentional omission of individual features allows her to transcend the specific and embrace the universal.

Key Interpretations of the Venus of Willendorf

Interpretation | Core Idea | Supporting Arguments | Counter-Arguments/Nuances |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fertility Figure/Mother Goddess | Embodies reproductive power, abundance, and the life-giving force, essential for group survival. | Exaggerated breasts, hips, belly common across Paleolithic 'Venuses'; importance of reproduction for survival in harsh environments; parallels to later fertility deities. | Some figures lack exaggerated features; not all cultures deified fertility in the same way; interpretations are often projected from modern viewpoints. |

| Self-Portrait | Created by a woman observing her own body from above, perhaps for introspection or artistic practice. | Explains distorted proportions (e.g., small feet, no face); subjective perspective; intimate scale. | Difficult to prove; assumes a specific mode of creation and artistic intent that is hard to verify over millennia. |

| Spiritual Object/Totem | Used in rituals, shamanism, or as a protective charm, perhaps holding magical or spiritual power. | Red ochre traces suggest ritualistic painting; portable nature suitable for nomadic spiritual practices; found in burial contexts with other grave goods. | Specific rituals are unknown; 'totem' can be broad and difficult to define precisely for the Paleolithic era. |

| Didactic Tool | Used to educate about female anatomy and reproduction, aiding in knowledge transfer within the community. | Simple, clear anatomical focus; valuable for knowledge transfer in pre-literate societies; could have served as an instructional aid for younger women. | Assumes a deliberate instructional purpose and a formal teaching structure, which might be an anachronism for the period. |

| Universal Womanhood | Represents woman as a universal concept, not an individual, embodying the essence of the feminine. | Lack of facial features universalizes identity; emphasis on shared female characteristics; she is woman rather than a woman. | Still rooted in specific cultural context and the worldview of the Gravettian people; may overlook individual cultural variations. |

| Good Luck Charm | Carried for protection, success in hunting, or safe childbirth, providing comfort and perceived influence. | Small, portable size; similar to modern amulets; practical purpose in a precarious world; easily transportable for nomadic groups. | Limited direct archaeological evidence specifically linking her to 'luck'; purpose often inferred from context. |

| Ancestral Figure | Represents a revered ancestor or foundational matriarchal figure, connecting the present to the deep past. | Emphasizes lineage and community; the abstract face could represent a timeless ancestor rather than a living person. | Difficult to distinguish from a generic 'goddess' figure; specific ancestral beliefs are unrecorded. |

Craftsmanship from the Stone Age

Think about working with stone without metal tools, millennia before the Bronze Age. It’s not just about brute force; it's about incredible patience, observational skill, and an intuitive understanding of your material. The Venus was meticulously carved using flint tools – perhaps blades for initial shaping, and burins or scrapers for finer details and smoothing. The evidence of careful shaping and polishing speaks volumes about the artisan's dedication. This level of craftsmanship, achieved with rudimentary tools, is truly astounding and points to a deep reverence for the object being created. What's more, the faint traces of red ochre found on her surface suggest she might have once been painted. Imagine that: a vibrant, reddish hue that would have made her even more striking, perhaps mimicking the warmth of blood, the vitality of life, or linking her to sacred earth and fertility rituals. The application of ochre wasn't merely decorative; it likely imbued the figurine with additional spiritual power. This wasn't just a utilitarian object; it was clearly something special, something imbued with profound care and likely significant ritualistic meaning. It makes you wonder about the elements of design they were considering, even way back then, to achieve such a powerful, almost timeless, form. They understood texture, form, and implied movement, even in such a small sculpture. It's a reminder that fundamental artistic principles are incredibly ancient.

Echoes Across Continents: Other Paleolithic Figurines

The Venus of Willendorf isn't an anomaly; she's part of a fascinating, widespread phenomenon known as 'Paleolithic figurines' or 'Venus figurines.' Across Europe and into Asia, archaeologists have unearthed dozens of similar carvings from the Upper Paleolithic period. These 'Venuses' (a modern, often debated, term, as we apply a classical goddess's name to prehistoric artifacts) share common characteristics like exaggerated female features, small size, and portability, yet each has its unique personality and regional stylistic variations. For me, this collective artistic output suggests a shared cultural significance, perhaps a common spiritual belief or social role for these female representations, stretching across vast distances and different tribal groups. The consistency of certain features across these diverse finds is truly remarkable and points to a deeply ingrained artistic and symbolic tradition.

Comparative Paleolithic Figurines

Figurine Name | Discovery Location | Estimated Age (BCE) | Material | Key Features/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Venus of Willendorf | Willendorf, Austria | 30,000 - 25,000 | Oolitic Limestone | Exaggerated feminine features, elaborate headwear, no discernible face, no feet; traces of red ochre. |

| Venus of Hohle Fels | Schelklingen, Germany | 35,000 - 40,000 | Mammoth Ivory | Oldest undisputed depiction of a human figure; emphasized vulva, no head, carved for suspension; small ring for hanging. |

| Venus of Dolní Věstonice | Dolní Věstonice, Czech Republic | 29,000 - 25,000 | Fired Clay | Oldest known ceramic artifact; exaggerated features, pinched head; often found intentionally broken, possibly as part of a ritual. |

| Venus of Lespugue | Lespugue, France | 26,000 - 24,000 | Mammoth Ivory | Highly stylized, abstract form; large, drooping breasts, prominent hips, tapering legs; almost geometric in its abstraction. |

| Venus of Brassempouy | Brassempouy, France | 25,000 - 23,000 | Mammoth Ivory | 'La Dame à la Capuche' (Lady with the Hood); one of the earliest realistic representations of a human face (though still abstract); distinctive coiffure. |

| Venus of Savignano | Savignano sul Panaro, Italy | 28,000 - 24,000 | Steatite | Stylized, elegant form; prominent breasts and abdomen, small head; often seen as more slender than other Venuses. |

| Venus of Laussel | Marquay, France | 27,000 - 22,000 | Limestone relief | One of the earliest bas-relief sculptures; a woman holding a bison horn with 13 notches, possibly representing lunar cycles or menstrual cycles. |

Its Place in the Grand Tapestry of Art History

The Venus of Willendorf holds an undeniable, foundational spot in the history of art. She is one of the earliest undisputed examples of human figurative art, offering a rare glimpse into the aesthetic and spiritual world of our Paleolithic ancestors. She stands as a potent symbol of humanity's earliest foray into artistic expression, a testament to our innate drive to create and communicate. When we trace the definitive guide to the history of abstract art: key movements, artists, and evolution all the way through to modernism, it’s humbling to think that the same impulse to represent, to abstract, to imbue form with meaning, has been with us for tens of thousands of years. From this tiny carving, we can see the very genesis of symbolism – the deliberate shaping of material to convey an idea beyond its physical presence. It’s quite the journey, isn't it, from a handheld fertility figure to a monumental abstract sculpture, yet the underlying human need to express, to connect, and to make sense of the world remains constant. For me, she represents the very bedrock of what would later become the diverse tapestry of human artistic endeavor.

Key Facts and Figures: The Venus of Willendorf at a Glance

Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| Era | Upper Paleolithic (Gravettian period), the Old Stone Age |

| Cultural Period | Gravettian culture, characterized by specific stone tools, elaborate burials, and portable art, active across Europe. |

| Estimated Age | 30,000 - 25,000 BCE (calibrated radiocarbon dating), making her one of the oldest known figurative artworks. |

| Discovery Date | August 7, 1908, by archaeologist Josef Szombathy. |

| Discovery Location | Near Willendorf, a village in Lower Austria, unearthed during systematic excavations of an Aurignacian-Gravettian settlement. |

| Archaeological Layer | Stratum IX, a distinct loess layer, crucial for its precise dating and contextual understanding of human occupation. |

| Material | Oolitic Limestone (a granular sedimentary rock), notably not indigenous to the region, strongly suggesting long-distance transport of either the raw material or the finished figurine. |

| Size | 11.1 cm (4.4 inches) tall; weighing approximately 15 grams (about half an ounce), making her highly portable. |

| Current Location | Permanently housed and displayed at the Naturhistorisches Museum (Natural History Museum) in Vienna, Austria. |

| Key Interpretations | Predominantly viewed as a fertility symbol or mother goddess, but also theorized as a self-portrait, a spiritual or shamanistic object, a didactic tool, or a good luck charm. |

| Distinguishing Features | Exaggerated feminine characteristics (voluminous breasts, wide hips, prominent belly), complete absence of facial features, intricate 'woven' or 'braided' headwear (or abstract hair pattern), and the lack of discernible feet, suggesting it was not meant to stand upright independently. Traces of red ochre indicate she was likely once painted. |

Even in a museum filled with classical sculptures, the profound simplicity and historical weight of the Venus of Willendorf would surely stand out. It’s that enduring power of a singular form to convey so much, a silent testament to the earliest stirrings of human artistry.

The Venus in the Modern Gaze: Legacy and Reinterpretation

It’s not just archaeologists and art historians who are captivated by the Venus of Willendorf. This tiny figurine has left an indelible mark on modern thought, influencing discussions in feminist archaeology, the study of human origins, and even contemporary art. Her universal, faceless form has become an icon, representing both the primal strength of the female and the enduring mystery of our distant past. She challenges our often Eurocentric views of early art, proving that sophisticated artistic thought and symbolic representation existed long before recorded history. For me, she's a constant reminder that art's power doesn't come from realism or intricate detail, but from its ability to resonate with something fundamental within us. Her presence forces us to reconsider the sophistication of early human cultures and their complex spiritual and symbolic worlds.

My Personal Reflection on the Venus's Enduring Appeal

My Personal Reflection on the Venus's Enduring Appeal and My Connection to Her

What strikes me most about the Venus of Willendorf isn't just her age, but her incredible, almost defiant, presence. She demands attention, not with intricate detail or dynamic pose, but with a raw, honest declaration of form. As an artist who often works with abstraction and bold colors, I find a deep kinship with that fundamental act of simplification and emphasis. She shows us that art doesn't need to be hyper-realistic to be powerful. In fact, sometimes the most profound statements come from distilling a concept down to its very essence, to its most primal form. She embodies a kind of primal abstraction that feels incredibly modern, a testament to the idea that the power of imperfection and embracing the inherent qualities of materials have always been a part of the creative journey. It reminds me a bit of the power of imperfection in embracing accidents and evolution in my own abstract art, finding beauty and meaning in the unrefined and the profoundly human.

She’s a reminder that art has always served a purpose beyond mere decoration – whether it was to communicate vital information, to invoke spiritual blessings, to celebrate the mysteries of life, or simply to express something deeply felt about the human condition. And that, I believe, is a connection that spans all of human history, from the Paleolithic artisans carving in icy conditions to the contemporary artist in a bustling city studio. It’s this enduring thread of human creativity that makes her story so compelling. If you're as fascinated by these ancient echoes as I am, perhaps exploring a timeline of art history might be your next adventure, or even considering a piece of my own abstract art that speaks to these timeless impulses and the raw, unpolished beauty of expression. After all, the urge to leave a mark, to create something meaningful, is a timeless human endeavor that connects us all.

Frequently Asked Questions about the Venus of Willendorf

- Q: What is the Venus of Willendorf?

- A: The Venus of Willendorf is a small, roughly 11.1 cm (4.4 inches) tall, prehistoric figurine of a female form, carved from oolitic limestone. She is believed to be one of the earliest known works of art, an iconic representation from the Upper Paleolithic era (30,000-25,000 BCE), known for her exaggerated feminine features and mysterious symbolic significance.

- Q: What is the significance of her missing face?

- A: The absence of discernible facial features is widely interpreted as a deliberate artistic choice to universalize the figure. Rather than representing a specific individual, she is thought to embody 'womanhood' itself, a collective ancestral mother, or a universal goddess figure. This lack of individual identity allows for a broader, more symbolic interpretation, inviting viewers across millennia to project their own meanings onto her.

- Q: When was the Venus of Willendorf discovered?

- A: The Venus of Willendorf was discovered on August 7, 1908, by archaeologist Josef Szombathy during excavations near Willendorf in Lower Austria. This discovery was crucial for understanding early human art.

- Q: Where is the Venus of Willendorf now?

- A: The original Venus of Willendorf is a prized exhibit, permanently housed and displayed in the Naturhistorisches Museum (Natural History Museum) in Vienna, Austria, where she continues to captivate visitors from around the world.

- Q: What does the Venus of Willendorf symbolize?

- A: While its exact meaning remains a subject of academic debate, the most prominent interpretations suggest she symbolizes fertility, a powerful mother goddess, or a protective good luck charm, reflecting the paramount concerns for reproduction, abundance, and survival in prehistoric societies. Other compelling theories propose she could be a form of self-portrait, a spiritual or shamanistic object used in rituals, or even a didactic tool for educating about the female body. Her lack of facial features further supports a universal rather than individual representation, inviting broader, archetypal interpretations of womanhood.

- Q: How old is the Venus of Willendorf?

- A: Based on calibrated radiocarbon dating of the archaeological layer where she was found, the Venus of Willendorf is estimated to be between 30,000 and 25,000 years old, placing her firmly in the Upper Paleolithic period (Old Stone Age).

- Q: What is oolitic limestone, and why is its origin significant?

- A: The Venus of Willendorf is uniquely carved from oolitic limestone, a granular sedimentary rock composed of ooids (small, spherical grains). This material is not indigenous to the Willendorf region in Austria where she was discovered. This geological fact is profoundly significant as it strongly suggests that either the Gravettian people who crafted her were nomadic and transported the raw material (or the completed figurine) from a distant geological source, or that it was acquired through ancient trade or exchange networks. This implies a level of mobility, resourcefulness, and cultural interaction among early humans that we might otherwise underestimate for this prehistoric period.

- Q: What was life like for the people who created her?

- A: The Venus of Willendorf was created by people of the Gravettian culture during the Upper Paleolithic period, a time dominated by the Last Glacial Maximum, characterized by a harsh, cold, and glacial climate across Europe. These were nomadic hunter-gatherers, highly skilled in crafting tools from stone, bone, and ivory, and adept at adapting to their challenging environment. Their survival hinged on collaborative hunting of megafauna like mammoths and reindeer, along with extensive foraging. Art, including portable figurines like the Venus and impressive cave paintings, was deeply intertwined with their spiritual beliefs, rituals, social cohesion, and their hopes for fertility and continued survival.

- Q: Who made the Venus of Willendorf?

- A: The precise identity of the artist (or artists) who carved the Venus of Willendorf is unknown and lost to time, as it dates to a period long before written records or individual artist attribution. She is understood to represent the collective artistic output and spiritual expression of the Gravettian people, a testament to the shared cultural consciousness of early human societies.

Delving Deeper into Ancient Art and Its Modern Echoes

The Venus of Willendorf reminds us that the urge to create, to express, and to find meaning through form is a deeply ingrained part of being human. It’s a journey that began millennia ago, in ice-age caves and nomadic camps, and one that continues to evolve and surprise us. If you’ve found yourself captivated by the whispers of the past, and the profound, sometimes raw, beginnings of human creativity, you might also enjoy exploring how the enduring influence of indigenous art on modern abstract movements continues to shape contemporary aesthetics, or perhaps a deeper dive into the definitive guide to the history of abstract art: key movements, artists, and evolution to see how artistic expression, from the primal to the philosophical, transformed over time. Each era, each culture, adds another layer to this incredible, ongoing story of humanity's creative spirit, proving that the impulse to make art is as old as humanity itself. This enduring thread of human creativity is, for me, one of the most compelling aspects of art history.