Hieronymus Bosch's Garden of Earthly Delights: An Artist's Deep Dive into Timeless Enigma

Join an artist's quest through Hieronymus Bosch's 'The Garden of Earthly Delights.' Explore its profound symbolism, diverse interpretations (from Surrealism to hidden heresies), and enduring impact on art and the human psyche. A truly captivating masterpiece.

Hieronymus Bosch's Garden of Earthly Delights: My Quest Through a Masterpiece of Earthly Delights and Endless Meanings

You know, there are some artworks that just grab you by the collar and refuse to let go. For me, Hieronymus Bosch's The Garden of Earthly Delights is one of them. Have you ever stood before a piece of art that felt less like a static image and more like a vibrant, chaotic, slightly disturbing fever dream committed to panel? That's my experience with this monumental triptych, now centered in Madrid's Museo del Prado. It’s a beautiful, bewildering, and profoundly human dream that, centuries after its creation, still mirrors our own often bewildering existence – a mix of ambition, desire, regret, and that constant, messy search for meaning. As an artist deeply invested in exploring complex emotions and abstract worlds, it’s a bit like diving into my own subconscious on a really creative, slightly chaotic day – messy, vibrant, and full of unexpected turns. This isn't just a painting; it's a triptych, a three-part altarpiece designed to be folded shut, revealing a haunting monochrome on its exterior. Each panel is a world unto itself, yet inextricably linked to the others. And here’s the wild part: after centuries, people are still arguing about what it all means. And who can blame them? It’s not exactly a straightforward narrative. It’s as if Bosch, with meticulous precision, scooped up his wildest thoughts, fears, and perhaps even his hopes, and just splattered them across this giant canvas. Join me as we unpack this monumental work, exploring its panels, the enduring mysteries of its meaning, and why it continues to captivate artists and thinkers like me. Ready to dive into the beautiful madness? If you're curious about the mechanics of such a form, what a triptych is in art is a great starting point.

Unveiling Bosch: Getting to Grips with the Artist and His World

But before we lose ourselves entirely in the myriad interpretations, let’s get a basic grounding in what this monumental work actually is, and the world it emerged from. To truly understand this visual explosion, we first need to understand the fertile ground from which it sprang. Imagine Europe at the dawn of the Northern Renaissance, a period of immense change, buzzing with intellectual ferment and deep anxieties. While the Italian Renaissance celebrated classical ideals, humanistic grandeur, and often idealized beauty, the North, particularly artists like Bosch, retained a deep imaginative tradition, focusing more on intricate detail, psychological depth, and sometimes, a grotesque realism that reflected the anxieties of daily life and religious morality. Think less of Michelangelo's heroic figures and more of the meticulously rendered, sometimes unsettling, details found in Flemish manuscript illuminations or early Netherlandish panel paintings – a tradition Bosch undeniably built upon. Humanism was beginning to flourish, challenging traditional medieval worldviews with a renewed focus on human potential and achievements. Yet, this wasn't simply a time of enlightenment; society was grappling with the lingering trauma of the Black Death, a rapidly expanding merchant class that brought both wealth and new moral dilemmas (I mean, money changes everything, right?), and the rise of bustling urban centers where traditional social structures were shifting. Religious fervor intertwined with burgeoning scientific inquiry, and the advent of the printing press meant ideas (and anxieties, like the fear of witchcraft, apocalyptic prophecies, or the coming Reformation) spread faster than ever. Bosch, uniquely positioned in the heart of this cultural ferment, was adept at reflecting these tensions. His distinct, almost visionary style, stood apart, aligning more closely with the deep imaginative traditions of Northern European art. Yet, its imaginative depth is, frankly, timeless.

The Garden of Earthly Delights was painted by Hieronymus Bosch, a Dutch master from the late 15th and early 16th centuries. His real name was Jheronimus van Aken, and he adopted 'Bosch' from his hometown, 's-Hertogenbosch (a city still rich in artistic heritage, where you can explore its history at the /den-bosch-museum). We don't know much about his personal life beyond his family of prominent painters and his membership in the influential Confraternity of Our Lady. This was a prominent religious brotherhood dedicated to the Virgin Mary, composed of both clergy and laypeople, and it played a significant role in the social and spiritual life of 's-Hertogenbosch. Being part of such a brotherhood suggests Bosch was well-connected and deeply embedded in the religious and social fabric of his community, potentially exposing him to morality plays, sermons, and theological discussions about free will, original sin, or even apocalyptic prophecies that might have fueled his allegorical imagination. This veil of mystery only adds to the allure of his work, I think; it’s almost as if he chose to let his paintings do all the talking. While records show he was a respected painter in his time, his unique, often unsettling vision meant his work didn't spawn legions of direct imitators but instead served as a singular, powerful voice. His designs, however, were widely disseminated through prints, influencing artists across the Low Countries and beyond, even if their direct style wasn't copied.

The painting itself is massive, measuring approximately 7.2 feet (2.2 meters) high and 12.8 feet (3.9 meters) wide when fully open. Imagine standing before a wall roughly the size of a small room, completely covered in intricate, vibrant details – it's an overwhelming experience that no photo can truly prepare you for. It's painted in oil on oak panels, a common medium of the era, but one that Bosch used with exceptional mastery. This allowed for the meticulous layering and vibrant, translucent glazes that give his work such depth and luminosity. Unlike the faster drying tempera, oils offered artists like Bosch the ability to blend colors seamlessly, create rich textures, and build up complex details over time, perfectly suited to his intricate visual narratives. His meticulous brushwork, often barely visible to the naked eye, allowed him to render every tiny creature, every delicate leaf, with astounding precision, contributing significantly to the richness and detail that truly reward close inspection. This painstaking technique is why this artwork has survived remarkably well over centuries, a testament to its careful conservation.

Likely intended for a private patron rather than a church, this might explain its audacious subject matter. A private patron – perhaps a wealthy nobleman or merchant with intellectual or even esoteric interests, like Count Hendrik III of Nassau – would have afforded Bosch greater artistic freedom, allowing him to explore themes of sin, temptation, and human folly in a way that a public church commission might have restricted. This move from purely ecclesiastical needs to individual tastes marks a growing sophistication of art patronage during the Northern Renaissance, a fascinating shift if you ask me. It’s a true spectacle, designed to be folded shut, revealing its outer panels. These outer panels depict the world in grisaille – a hauntingly beautiful monochrome painting technique, typically used to simulate sculpture in shades of grey or brown. When closed, it shows a sphere of water and land, a nascent Earth just after its creation, before humanity. It's a serene, almost desolate image, painted with such precision it truly does look like a carved relief. This quiet, unpopulated world, before humanity's arrival, subtly hints at the profound narrative about to unfold, creating a powerful sense of anticipation for the viewer. If you're curious about this fascinating technique, you can learn more about what grisaille is in other art contexts. But trust me, it’s the inner panels, bursting with color and life (and sometimes death), that truly steal the show. Over centuries, the triptych changed hands several times, notably acquired by Philip II of Spain, eventually finding its permanent home at the Museo del Prado in Madrid, Spain, where it has resided since 1939, making it accessible to millions. Knowing its journey, and that it hung in Spanish royal collections for centuries, really underscores its enduring power.

Panel by Panel: A Whimsical Walkthrough (and My Initial Thoughts)

Now that we have a foundational understanding of Bosch and his world, let's dive headfirst into the layers of his masterpiece, starting from the beginning. From subtle unease to glorious chaos, and then a chilling descent – it’s a narrative arc I can't get enough of. As an artist, I always look for how a story unfolds visually, and Bosch's narrative choices here are nothing short of genius.

The Left Panel: Paradise – The Fleeting Innocence of Eden

This is usually considered the "Paradise" panel, depicting God presenting Eve to Adam in the Garden of Eden. Seems simple enough, right? Wrong. Bosch, in his typical fashion, throws in a whole menagerie of peculiar animals: a giraffe, an elephant, and some decidedly unsettling hybrid creatures, like a fish-tailed human emerging from water or a bizarre three-headed beast in the foreground. I always wonder what was going through his head to combine these! There’s a cat carrying a mouse in its mouth, an owl looking suspiciously from a dark hole (owls often symbolized evil or heresy in Bosch's time, fun fact!), and other scenes of animal predation. Even within this supposed Eden, the seeds of corruption and a disordered natural world are subtly present. For instance, the ominous dragon tree looms prominently; it’s frequently interpreted as a symbol of evil or a twisted representation of the Tree of Knowledge, subtly foreshadowing the Serpent's temptation and the coming Fall. And those animals preying on each other? It's a stark visual hint at a world already imperfect, already showing the first cracks of entropy. I always feel like God looks a little... tired, or perhaps even resigned, as if he already knows how this story ends. This panel, though vibrant, subtly plants the seeds of unease that blossom into the chaotic central scene. It's almost like Bosch is whispering, 'Don't get too comfortable; trouble is brewing.' For me, as an artist, this panel's brilliance lies in its ability to introduce tension and foreshadowing even amidst beauty – a powerful lesson in visual storytelling.

Key Details to Observe:

- The subtle predatory actions among animals (cat and mouse, lion devouring a stag).

- The melancholic or resigned gaze of God.

- The strangely hybrid creatures (fish-tailed human, three-headed beast) that hint at something unnatural even in paradise.

- The dark, foreboding presence of the owl and the dragon tree.

The Central Panel: The Garden – Grand, Glorious Chaos

Ah, the heart of the enigma! This is "The Garden" itself – a sprawling landscape teeming with hundreds of nude figures, giant fruits, exotic birds (some impossibly sized), and strange, often translucent, structures. Everyone seems to be engaged in a kind of joyous, uninhibited play. They ride enormous animals like deer and panthers, swim in pools with other figures, and interact in ways that are both innocent and suggestive. There’s a striking abandon, a freedom that borders on being unburdened by shame. This panel is bursting with a variety of visual elements:

- Nude Figures: Hundreds of men and women, seemingly unburdened by shame, interacting playfully, sometimes intimately, in various communal activities. It’s an ideal that feels both primal and almost utopian, perhaps reflecting a pre-lapsarian innocence, or conversely, a world utterly lost to sensual desire.

- Giant Fruits: Enormous strawberries, cherries, grapes, and other berries are frequently consumed by the figures. These are often interpreted as symbols of fleeting earthly pleasures, or even as allegories for the seven deadly sins – strawberries for lust and envy, cherries for gluttony, for example. Their sheer abundance suggests an overindulgence, a world where desires are not just met but actively celebrated. I sometimes think of them as nature's fleeting candy, dangerously alluring.

- Exotic & Oversized Animals: Figures ride on panthers, deer, griffins, and interact with impossibly large birds like the hoopoe (a bird sometimes associated with foolishness or promiscuity) or parrot (often symbolizing vanity or even deception). These animals, often exotic, further contribute to the fantastical, almost alien, atmosphere.

- Bizarre Architectural Structures: Transparent tubes, bubbles, and crystalline forms are often seen as alchemical vessels, ephemeral symbols of human folly, or perhaps even early scientific curiosities. You might spot people emerging from enormous clam shells or interacting within these spheres. These structures feel both natural and entirely unnatural, adding to the panel's dreamlike quality – like something you'd see in a fever dream. The fleeting nature of bubbles, in particular, always strikes me as a potent symbol of transient pleasure.

- Water Rituals: Men and women bathing together in shallow pools, often surrounded by spheres or tubes, engaging in communal, seemingly innocent, yet potentially suggestive activities, evoking themes of purification or primal interaction. The central pool with women and the surrounding ring of men on horseback feels like a grand, ritualistic dance.

When I look at this panel, I often think about desire, about what it means to truly want something, unburdened by societal judgment, before the rules get written. It's a vision of communal living that's both alluring and slightly alien, a place where the lines between innocence and hedonism (the pursuit of pleasure as the highest good, which in Bosch's era could encompass gluttony, lust, and vanity) are deliciously blurred. Is it heaven on Earth? Or is it a trap, a temporary pleasure leading to something darker? The sheer volume of detail, the vibrant and almost psychedelic colors – from luscious greens to striking blues and reds – the sheer weirdness of it all – it’s overwhelming in the best possible way. This joyous revelry, however, has a distinct, terrifying end. The careful consideration of color in Bosch's work — where vibrant hues might mask deeper anxieties — reminds me how the psychology of color plays a profound role in how emotions are conveyed in contemporary art, a theme often explored in the psychology of color in abstract art.

Artistic Takeaway: The visual density and riot of color here are a masterclass in controlled chaos. Bosch floods the canvas with so much information that the viewer is forced to slow down, explore, and find their own narrative. It’s a technique I often try to emulate in my own abstract works – creating worlds so rich in detail that every viewing reveals something new.

Key Details to Observe:

- The vast number of nude figures and animals, creating a sense of bustling activity.

- The recurring giant fruits, often being eaten or held, symbolizing fleeting pleasure or sin.

- The strange, transparent bubbles and architectural structures that feel both natural and unnatural.

- The playful, sometimes intimate, interactions among the figures, and the subtle undercurrent of indulgence that permeates the scene.

The Right Panel: Hell – Welcome to Bosch Style

And then we have this. The "Hell" panel. If the central panel is a dream, this is the nightmare. The contrast is visceral, like a punch to the gut after the visual feast of the Garden. Dark, desolate, and filled with torment, it’s a terrifying descent into consequences. Musical instruments, so often associated with harmony and pleasure, become instruments of torture – a giant harp with a naked figure crucified upon its strings, a lute used to pin someone down, drums becoming tables of agony, and I swear, I even see people being tormented by a giant recorder! Bosch brilliantly depicts the psychological horror of it; the perversion of something beautiful into a tool of suffering is a truly chilling concept. Who ever thought a flute could be so terrifying? It’s a stark reminder that even the most beautiful things can be twisted into tools of suffering, and that every action, especially one driven by unchecked desire, might have a horrific price. It's an inventive, disturbing vision of damnation that still resonates today, capturing a universal sense of dread. It makes me wonder what daily fears Bosch might have been channeling into these grotesque scenes – perhaps the fear of invasion, plague, or social collapse that plagued his era.

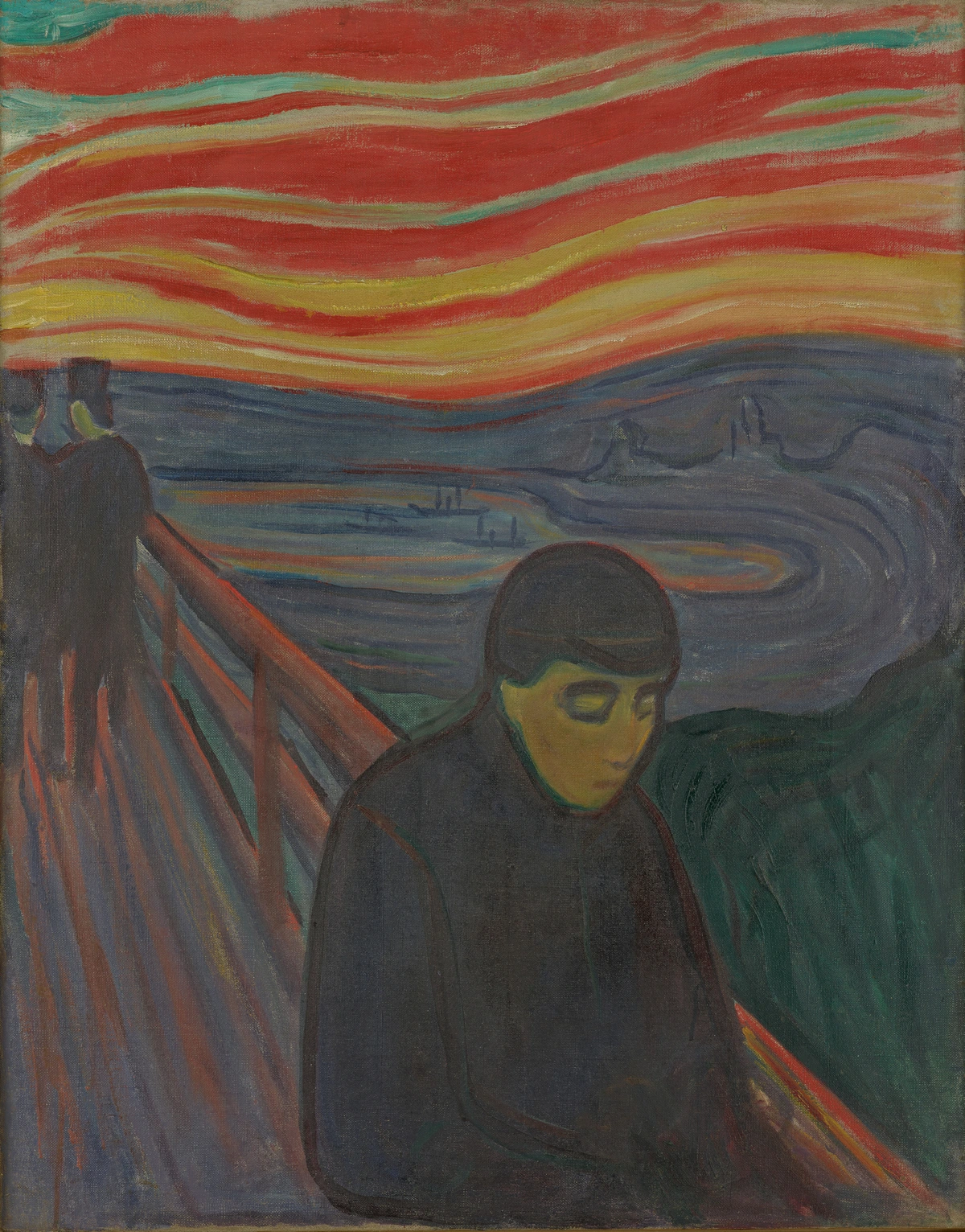

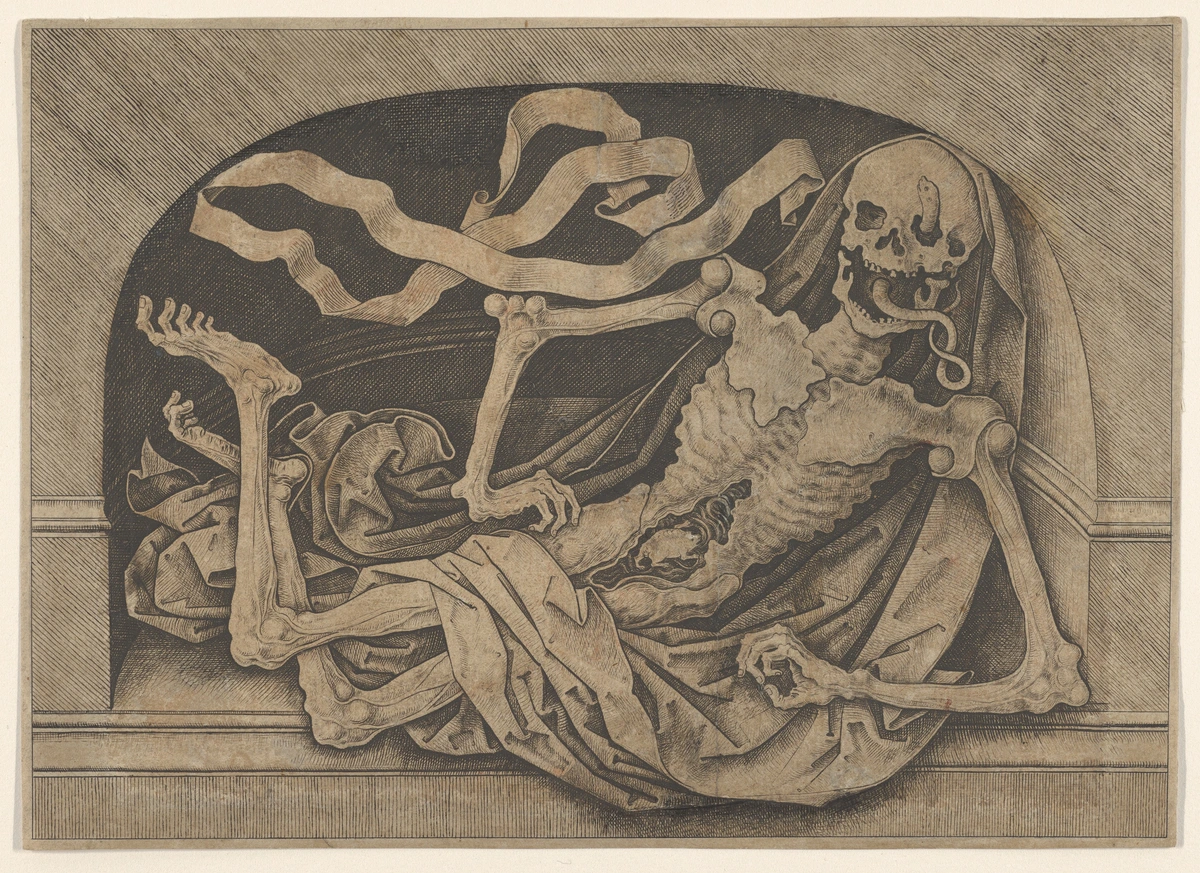

The sheer inventiveness of Bosch’s torments, from the iconic "tree-man" who stares out with his hollow body (often interpreted as self-imprisonment or a corrupted 'second Adam', his legs resembling decaying tree trunks, making him both a witness and a participant in the suffering), to figures frozen in ice or consumed by fire and devoured by grotesque beasts, reflects the deepest fears of his era. It’s a powerful memento mori (a symbolic or artistic reminder of the inevitability of death), a stark reminder of mortality and the potential for eternal suffering, a theme explored in art across centuries, much like Edvard Munch's The Scream captures a similar existential dread.

Artistic Takeaway: This panel is a masterclass in visual tension and symbolic storytelling through grotesque imagery. The way familiar objects are subverted for torture, or the chilling resignation on the tree-man's face, shows how powerful emotional impact can be achieved by twisting the familiar. It’s a dark mirror to the central panel's riot of color, proving that true artistry can evoke the full spectrum of human experience.

Key Details to Observe:

- The creative and often grotesque punishments, especially how familiar objects (like musical instruments) are repurposed for torture.

- The iconic tree-man, with his hollow body and melancholic gaze, and legs resembling decaying tree trunks.

- Figures subjected to elemental torments (frozen in ice, consumed by fire).

- Grotesque, hybrid demons devouring and punishing humans in various inventive ways.

So, What Does It ALL Mean? (Theories I've Encountered and Pondered)

This is where the real fun begins, because there's no single, universally accepted answer. And frankly, I absolutely love that about it. Art doesn't always need a definitive explanation; sometimes, the beauty is in the endless conversation, the continuous probing of its depths. Bosch himself left no written explanations, leaving us to piece together the puzzle from the echoes of his time and our own evolving perspectives. It's a mystery that art historians have wrestled with for centuries, ensuring its place as one of the most debated artworks in history. The beauty is in the multitude of perspectives it invites, each offering a fascinating lens. Let's delve into some of the most compelling interpretations I've encountered, always remembering that Bosch likely intended a layered meaning, where different interpretations could coexist, adding to its enigmatic power:

Interpretation | Key Tenets | Supporting Evidence (Brief) | Personal Resonance |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Original Surrealist | Bosch tapped into subconscious, dream logic, and the absurd centuries before the movement. | Bizarre juxtapositions, illogical scale, Freudian undertones, dreamlike imagery. | Captivating for its revolutionary foresight; feels incredibly modern, a true visionary. |

| Traditional Moral Warning | A Christian sermon in paint, depicting humanity's fall from grace through sin and the inevitable damnation. | Progression from Eden to hedonistic Garden to Hell; pervasive religious anxieties of the era (e.g., fear of damnation, free will debates). | Historically influential, but feels almost too neat for such a wildly imaginative complexity. |

| Pre-Lapsarian Paradise | The central panel shows humanity in an innocent state before the Fall, without shame or knowledge of good/evil. | Joyful nudity, harmonious interaction with nature, absence of overt sin in the central panel, echoes of apocryphal texts. | A poignant "what if"; makes the Hell panel's contrast even more devastating, a fleeting moment of pure innocence. |

| Alchemy, Gnosticism, Esoteric Symbolism | Hidden meanings related to spiritual transformation, secret knowledge, or philosophical systems. | Transparent vessels (alchemical retorts), specific birds (peacock for immortality), symbolic colors/fruits, echoes of hermetic traditions. | Intriguing layers of hidden meaning, transforming the painting into a cryptic puzzle that invites deep research. |

| Adamite Heresy / Free Spirit Brotherhood | The central panel depicts a literal "Earthly Paradise" as envisioned by specific medieval mystical sects. | Communal nudity, free love, rejection of societal norms, seeking a return to primal innocence, connection to millenarian movements. | Provides a historical context for the radical subject, explaining the uninhibited freedom, challenging conventional readings. |

Bosch: The Original Surrealist? Ahead of His Time

This is my personal favorite angle, even if it's wonderfully anachronistic. Long before André Breton penned his manifestos, Bosch was crafting dreamscapes that would make any surrealist proud. The bizarre juxtapositions – like a man with flowers for a head, or figures encased in bubbles – the illogical scale, the Freudian undertones (naked bodies, strange desires, nightmarish creatures) – it all feels incredibly modern to me. It's as if Bosch tapped directly into the collective unconscious, pulling out archetypes and fears that still resonate today. He was creating a visual language of the absurd and the subconscious centuries before it became an "art movement," utilizing dream logic and the juxtaposition of disparate elements that are hallmarks of surrealism. As an artist, I find this truly revolutionary; it demonstrates his unparalleled visionary genius, a true precursor to the dreamscapes of artists like Dalí, Max Ernst, and even the more abstract, yet equally dreamlike, works of Joan Miró. It’s almost like he saw the future of art in his nightmares and visions.

The Traditional Moral Warning: A Sermon in Paint

While the surrealist interpretation is personally appealing, this is, by far, the most common and historically influential interpretation. Many scholars, reflecting the dominant religious anxieties of Bosch's era – debates about free will, original sin, and the path to salvation – view The Garden of Earthly Delights as a profound Christian moral warning. The left panel is Eden before the Fall, the central panel depicts humanity succumbing to worldly pleasures and sinful lust – a direct path to damnation. The right panel then serves as the terrifying, inevitable consequence. It’s a classic sermon in paint, a cautionary tale against vice, showing humanity's departure from God's grace through unchecked indulgence. This perspective speaks directly to the pervasive fear of eternal punishment, a very real concern for people in the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance. When I first learned about this, it made a lot of sense, but it still felt a little too... neat for such a wildly imaginative and complex painting, almost too straightforward for Bosch's intricate mind. He was, after all, a member of a religious confraternity, so this reading certainly aligns with his societal context.

A Pre-Lapsarian Paradise: Innocent Bliss

Some scholars propose a more nuanced view: that the central panel isn't about sin at all, but rather a depiction of humanity before the Fall, in a truly innocent state where there was no shame in nudity, physical pleasure, or direct interaction with nature. It suggests a kind of blissful ignorance, where humanity lived in harmony without knowledge of good and evil, a literal "earthly paradise" as perhaps envisioned in some early Christian thought or apocryphal texts, such as the Book of Genesis and early mystical writings, that depicted a state of natural purity prior to temptation. This interpretation resonates with me a bit more because it allows for the joyous, vibrant quality of the central panel to be truly innocent, making the shock and horror of the Hell panel an even more abrupt and devastating contrast. It’s a poignant "what if" scenario beautifully painted – a fleeting moment of perfection before everything went wrong. It highlights Bosch's daring to imagine a different kind of Eden, one where innocence is both glorious and terribly fragile.

Alchemy, Gnosticism, and Esoteric Symbolism: Cryptic Messages

Now we're getting into the really juicy, speculative stuff! These interpretations delve into more obscure realms, connecting the painting to alchemy – the ancient practice of chemical transformation, often symbolizing spiritual purification and the transformation of base matter into gold (or, more metaphorically, the soul's refinement) – or Gnosticism, an early Christian philosophical movement emphasizing esoteric knowledge and spiritual enlightenment over conventional teachings. These ideas, while not mainstream, circulated among intellectual and spiritual circles in Bosch's time. Proponents of these theories suggest various elements within the painting might represent alchemical processes, stages of spiritual transformation, or hidden Gnostic messages. For instance, the transparent tubes and bubbles in the central panel, reminiscent of laboratory glassware, could be seen as alchemical retorts or purification vessels, symbolizing the opus magnum (the great work) of alchemy – the quest for ultimate transformation. Meanwhile, the distinct symbolism of water or specific birds like the peacock (often associated with immortality or spiritual transcendence in esoteric traditions) might carry deeper, mystical meanings related to esoteric purification or the journey of the soul. These theories are fascinating, if hard to prove definitively, often requiring deep dives into obscure texts and symbols from Bosch's era, truly turning the painting into a cryptic puzzle. I mean, who doesn't love a good mystery, right? It's like finding a hidden meaning in something familiar, a bit like the enduring allure of Leonardo da Vinci's works and the Mona Lisa's enigmatic smile – always inviting new interpretations. But it’s crucial to remember, these are scholarly interpretations, not confirmed intentions of Bosch, which makes them all the more intriguing to ponder.

The Adamite Heresy: A Return to Innocence?

One particularly intriguing, though highly speculative, theory links the central panel to the Adamite heresy or the Free Spirit Brotherhood – medieval mystical sects that advocated a return to the state of primal innocence before the Fall. For these groups, there was no shame in nudity, as it was considered humanity's original, sinless state. They sometimes practiced communal nudity, rejected traditional social norms, and believed in living in a state of unburdened purity, seeking to recreate an earthly paradise. These were part of broader millenarian movements that believed in a coming spiritual transformation, often seeing themselves as living in a new age of the Spirit. For the average person in Bosch's devout society, such practices would have been scandalous, highlighting the radical nature of this interpretation. While direct evidence linking Bosch to these specific sects is scarce, the central panel's depiction of uninhibited nudity, communal interaction, and apparent freedom from moral judgment aligns remarkably with their theological ideals. It offers a radical perspective on The Garden, suggesting it might not be a warning against sin, but rather a depiction of an idealized, albeit controversial, spiritual freedom. It’s a compelling "what if" that challenges conventional readings and reminds us of the diverse, sometimes clandestine, spiritual currents of the era.

Bosch's Enduring Legacy: Influence and Inspiration

From the depths of its diverse meanings, Bosch’s impact extends far beyond his own time. The audacity and sheer imaginative power of The Garden of Earthly Delights didn't just shock his contemporaries; it laid groundwork for future generations of artists. Long before Surrealism became a defined movement, Bosch was exploring the subconscious, the absurd, and the dreamlike, influencing figures centuries later from Pieter Bruegel the Elder (who shared Bosch's satirical eye and interest in peasant life) to the 20th-century Surrealists like Salvador Dalí and Max Ernst. His work's influence also extends beyond the visual arts, subtly permeating literature, film, and even philosophical thought that grapples with the nature of reality and the human psyche. His willingness to push boundaries, embrace ambiguity, and infuse his work with an intensely personal vision demonstrated that art could be a conversation, a challenge, a dream, and a nightmare, all at once. It's fascinating to consider how this monumental work, after being admired by Spanish royalty and passing through private collections, gained even wider recognition when it entered public display, allowing its enigmatic power to resonate with an ever-growing audience across different eras, truly solidifying its place in art history.

For instance, I often see echoes of Bosch's chaotic beauty and intense psychological exploration in the works of artists like Jean-Michel Basquiat. Basquiat's vibrant, neo-expressionist pieces, with their bold lines, layered symbolism, and raw, often disturbing imagery of skulls and fragmented bodies, capture a similar spirit of grappling with profound human experience, albeit in a different era. Both artists create worlds that are visually overwhelming, inviting endless interpretation while simultaneously confronting us with uncomfortable truths about our inner and outer lives. It's a testament to Bosch's enduring vision that it still feels so relevant in contemporary art.

Practicalities of Viewing: Experiencing the Masterpiece at the Prado

If you ever find yourself in Madrid, a visit to the Museo del Prado to see The Garden of Earthly Delights in person is an absolute must. Trust me, standing before it, the sheer scale and meticulous detail become overwhelmingly apparent in a way no reproduction can truly convey; it's a transformative experience. Here are a few tips for making the most of your encounter:

- Allow Ample Time: This isn't a piece you can rush. Dedicate at least an hour, if not more, to truly absorb the details of each panel. Move closer, step back, let your eyes wander.

- Observe the Triptych's Full Cycle: Start by appreciating the serene grisaille of the closed outer panels, then marvel at the explosion of color and life within. Understanding this visual progression is key.

- Seek Out Specific Details: Armed with some knowledge of the interpretations, try to find the dragon tree, the tree-man, the transparent bubbles, and the musical instruments of torture. Each tiny figure tells a story.

- Utilize Resources: Consider grabbing an audio guide or a museum guidebook. They often provide invaluable insights and guide you through the countless details you might otherwise miss.

- Embrace the Crowds & Check Regulations: It's one of the most famous paintings in the world, so expect company. Try to find moments when the crowd thins, or simply let yourself be part of the shared awe. And always check the Prado's specific viewing regulations beforehand – for instance, flash photography is almost always prohibited. Seeing it in person is an experience that stays with you long after you leave.

Why It Still Haunts Me (and Maybe You Too)

I think The Garden of Earthly Delights continues to fascinate and even haunt us because it stubbornly refuses to be pinned down. It mirrors the messy, contradictory nature of our own existence – a constant grapple with temptation, the pursuit of pleasure, the facing of consequences, and often finding ourselves in bewildering situations. Bosch gives us a mirror, albeit a very strange, warped one, reflecting the universal human condition across centuries. From its initial shock and awe to its enduring influence on artists and thinkers, its story is as complex as the painting itself. I see its reflection everywhere, from the fleeting digital pleasures of our age to the urgent anxieties about our planet's future, and the timeless struggle between individual desire and collective well-being. It’s all there in Bosch.

The sheer imagination, the audacious creativity, the willingness to depict humanity in all its glorious, grotesque, and vulnerable forms – that's what makes it timeless. As an artist myself, deeply invested in exploring complex emotions and abstract worlds, Bosch’s work teaches me that pushing boundaries and embracing ambiguity can create something truly profound and enduring. When I think about my own use of vibrant, sometimes clashing colors, or my exploration of abstract forms that defy easy explanation, I'm often drawing from that same spirit of bold inquiry and visual complexity that Bosch embodied. His ability to fuse the mundane with the fantastical, to present both utopian ideals and nightmarish realities within a single frame, profoundly influences my desire to create art that invites viewers to find their own unique meanings and connections. Perhaps you'll find some of that same spirit in the art I create, delving into visual narratives that defy easy explanation and invite profound personal reflection, available to buy online and bring that touch of beautiful madness into your own space, or discover more about my own artist's journey and how it echoes similar quests.

Frequently Asked Questions

Before we wrap up our journey through Bosch's masterpiece, here are some burning questions many people have about this extraordinary work. It's a good way to tie up any loose ends and reinforce some key takeaways!

Q: Who painted The Garden of Earthly Delights? A: It was painted by the Dutch master Hieronymus Bosch, whose real name was Jheronimus van Aken. He took his artistic surname from his birthplace, 's-Hertogenbosch.

Q: When was The Garden of Earthly Delights painted? A: The exact date is debated, but it's generally believed to have been completed between 1490 and 1510.

Q: Where is The Garden of Earthly Delights located today? A: This incredible triptych is housed at the Museo del Prado in Madrid, Spain, where it has been since 1939.

Q: What is the main message of The Garden of Earthly Delights? A: That's the million-dollar question! There's no single agreed-upon message, and its ambiguity is part of its enduring appeal. It's often interpreted as a moral warning about earthly pleasures leading to damnation, a depiction of humanity before the Fall, or even a complex alchemical, Gnostic, or Adamite allegory. The painting's power lies in its multi-layered nature, encouraging each viewer to find their own meaning.

Q: What makes The Garden of Earthly Delights so unique? A: Its uniqueness stems from its unparalleled imagination, intricate symbolism, and visionary depiction of both paradise and hell. Bosch's ability to blend the fantastical with deeply moral and spiritual themes, combined with his distinctive, almost surreal style, set it apart from contemporary works and continues to captivate audiences worldwide. The vibrant colors and meticulous detail, preserved remarkably well, also contribute to its lasting impact.

Q: What are some common misconceptions about The Garden of Earthly Delights? A: One common misconception is that Bosch's work is purely a product of madness or random imagination; in fact, it's deeply rooted in the philosophical, religious, and social contexts of his time, albeit expressed through a highly idiosyncratic vision. Another is that there's a single, definitive "key" to understanding it, when its enduring power lies precisely in its multi-layered, open-ended interpretations. It's also sometimes mistakenly seen as purely didactic, overlooking its immense artistic and psychological complexity.