Conceptual Art: The Definitive Curator's Guide to Idea, Meaning, & Enduring Impact

Unravel Conceptual Art with Zen Dageraad Visser. Dive into its ideas-first philosophy, pivotal artists, global reach, and profound relevance in contemporary art, NFTs, and beyond. Your definitive guide to art that makes you think.

Conceptual Art: The Definitive Curator's Guide to Idea & Meaning, From My Studio to Your Mind

For years, I've found myself utterly captivated by art that makes you think more than it makes you simply see. There's a particular kind of thrill that comes from grappling with an idea, letting it unfold in your mind, rather than just admiring a perfectly rendered surface. Wandering through galleries, engaging with pieces, and honestly, sometimes feeling utterly bewildered, one movement consistently sparks the most robust conversations among art lovers and newcomers alike: Conceptual Art. It's frequently misunderstood, occasionally dismissed, and yet, for me, it represents one of the most profoundly influential shifts in modern art history. This wasn't just a stylistic pivot; it was a quiet revolution that fundamentally changed the art market and gallery landscape, demanding a re-evaluation of what art could be. But what is it, truly, and why does it still matter so much today? What if the most profound artwork wasn't something you could hang on a wall, but something that happened entirely within your mind? In this guide, I, as an artist and curator, will demystify Conceptual Art, exploring its core principles, influential figures, and enduring relevance, aiming to make it your ultimate resource.

To me, approaching Conceptual Art feels less like admiring a beautifully crafted object and more like being invited into a fascinating, sometimes bewildering, philosophical debate. It demands a different kind of looking, a different kind of thinking. And that, my friends, is where its enduring power lies. It sparked a quiet revolution, training us to read art not just with our eyes, but with our minds, seeking deeper layers. In this guide, we'll unravel the core ideas, explore its historical roots, dissect its key principles, celebrate its pioneers, and understand its enduring relevance today.

Rodin's 'The Thinker' is a classic example of art inspiring contemplation, but imagine if the act of thinking, or the idea of contemplation, was the artwork itself, documented only by a photograph of someone pondering. That's the conceptual leap.

What is Conceptual Art, Really? Unpacking the Core Idea

Before we dive into the 'how,' let's really wrestle with the 'what.' What if art wasn't about beauty, but about a provocative thought? That's the audacious question Conceptual Art poses. At its core, Conceptual Art is a revolutionary art movement where the idea or concept behind the artwork is considered paramount, often to the exclusion of traditional aesthetic, technical, and material concerns. I know what you’re probably thinking: "So, the object itself isn't important?" Well, not in the way we usually think about it, no. The finished piece might be a photograph, a text, a performance, a map, or even just a set of instructions. The physical manifestation is merely a temporary, often unassuming, vehicle for the profound idea it carries. It's the intellectual agility, the audacity of the concept, that becomes the true 'masterpiece.'

This was a truly radical departure, emerging strongly in the mid-1960s and 1970s. Artists were, quite frankly, tired of the art object's commodity status – tired of art being just another pretty thing to buy and sell. I've seen firsthand how the pressure to produce 'sellable' art can stifle creativity, forcing artists to prioritize market appeal over genuine artistic inquiry. This pressure, to conform to what sells, often leads to a dilution of radical ideas and an emphasis on the tangible, collectible 'product.' Conceptual artists actively challenged this by creating works difficult or impossible to collect and commodify in the traditional sense. Think of art that was ephemeral, site-specific, or purely textual, making it hard to transport, store, or display in a typical gallery. This wasn't just a stylistic shift; it was an intellectual call to arms, demanding deeper engagement from the viewer, forcing a re-evaluation of what constituted artistic value. The art market, accustomed to tangible goods, scrambled to define value for works lacking a physical 'thing' to collect; I recall countless conversations with gallerists trying to price a piece that was essentially a certificate or a set of instructions – the paradoxes were fascinating, and often quite frustrating, to navigate!

The Conceptual Shift: Idea Over Object

Traditional Art Focus | Conceptual Art Focus | Radical Shift From | Underlying Question Posed by the Art | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aesthetic beauty, craftsmanship | Idea, meaning, intellectual inquiry | Abstract Expressionism's gestural emphasis, Pop Art's consumer culture embrace | "What is beauty?" or "How is this made?" | A Rembrandt portrait vs. Kosuth's One and Three Chairs |

| Unique, tangible object | Concept, process, instructions, documentation | The 'masterpiece' as a singular, precious, collectible item | "What is art's physical form?" or "Can art be intangible?" | A Rodin sculpture vs. Sol LeWitt's wall drawing instructions |

| Emotional response (often visual) | Intellectual engagement, critical thought | Passive appreciation of visual spectacle and immediate sensory gratification | "How does this make me feel?" vs. "What does this make me think?" | A Rothko color field vs. Yoko Ono's Instruction Pieces |

| Mastery of materials/technique | Execution serves the idea, often minimal | Emphasis on the artist's 'hand,' technical virtuosity, and material manipulation | "What is the artist's skill?" vs. "What is the artist's idea?" | A Michelangelo fresco vs. Lawrence Weiner's text pieces |

The Historical Roots of Idea-Driven Art: Seeds of a Revolution

But the seeds of Conceptual Art were planted much earlier. I always point to Marcel Duchamp as the mischievous, revolutionary ancestor, particularly with his "readymades" (everyday manufactured objects designated by the artist as works of art by virtue of the artist's intellectual choice, not manual craft). His Fountain (1917), a porcelain urinal presented as sculpture, wasn't asking us to admire its beauty, but to ponder the very nature of art, authorship, and the role of the institution in declaring what is art. This was, in essence, a profoundly conceptual act, questioning the very core of artistic value. Duchamp shrewdly understood that by simply signing and exhibiting a mass-produced object, he shifted the burden of 'art-ness' from the object's inherent qualities to the institutional context (the gallery, the exhibition, the art world's acceptance) and the artist's conceptual choice. This act of recontextualization, more than the object itself, was his true masterpiece. Think also of his Bicycle Wheel (1913), an ordinary bicycle wheel mounted on a stool, inviting viewers to engage with its kinetic potential as an aesthetic object, or even the Bottle Rack (1914), a metal bottle drying rack that Duchamp simply signed. These works dismantled the idea that art needed to be 'made' by the artist's hand, placing the emphasis squarely on the artist's intellectual choice.

Figures from Dadaism and Surrealism also toyed with anti-art sentiments and challenging conventions, directly paving the way for idea-driven art. Dadaists, for example, used manifestos, performance, and collage to disrupt traditional art forms and societal norms, focusing on absurdity and questioning logic, which championed an intellectual, rather than purely aesthetic, approach. Surrealism, with its exploration of the subconscious and dream imagery, sought to subvert conventional reality, creating a space for art to exist as a mental construct beyond mere representation. Even earlier, Symbolism prioritized subjective ideas and emotions over realistic depiction, urging viewers to look beyond the visible for deeper meaning, thus subtly foreshadowing the conceptual shift. Futurism, with its emphasis on motion, technology, and breaking from tradition, also contributed through its manifestos and performative events, shifting focus to the artist's declaration and the experience rather than solely the static object.

However, Conceptual Art pushed this into a realm of pure intellectual inquiry, often informed by linguistic philosophy, such as the ideas of Ludwig Wittgenstein on language games and meaning. Wittgenstein’s work, particularly his concept of "language-games," suggested that meaning is derived from how words are used within specific contexts, rather than from an inherent, fixed meaning. (Think of how the word "bank" means something entirely different when discussing a river versus a financial institution.) Conceptual artists, like Joseph Kosuth, applied this, treating art itself as a language system, exploring how context, definition, and presentation shape our understanding of an artwork, challenging the viewer to decipher the "rules" of the art-game being played. Kosuth, in particular, saw art as a proposition about art itself, often employing tautologies – statements true by virtue of their meaning, like "A chair is a chair" – to explore the structure of language and perception. For Kosuth, this seemingly simple statement wasn't a given; it was a way to strip away assumptions, compelling us to consider how we define and understand even the most basic objects, and by extension, art itself. It's a bit like taking a word, putting it under a microscope, and asking, "But what is 'chair,' really? What does it mean?"

I remember vividly standing before a piece once—it was just a typed statement on a wall. My initial reaction was, "That's it?" But as I read and absorbed, the layers of meaning unfolded, revealing the profundity of the artist's inquiry. That's the magic, right there: the moment an idea transcends its humble presentation and sparks a revelation in your mind. It’s a feeling I strive for in my own abstract work; that moment when a collection of colors and forms, like a well-crafted sentence, unlocks a powerful, unexpected thought.

Key Principles & Defining Characteristics of Conceptual Art: A Curator's Lens

This fundamental shift laid the groundwork for the core principles that define Conceptual Art, which we will now explore in detail. Think of them as the artist's toolkit and philosophical compass. Conceptual art isn't a monolith; it’s a spectrum of practices unified by a few core tenets that, to my mind, remain endlessly fascinating. Think of these as the guiding stars for anyone trying to navigate this intriguing landscape, constantly asking, "What question is the artist posing?" I find that understanding these principles is like learning the secret handshake to a very exclusive, yet ultimately liberating, club.

Core Pillars of Conceptual Art: A Quick Overview

Pillar | Description | Why it matters (from my perspective) |

|---|---|---|

| Idea over Object | The concept is paramount; the physical form is secondary or serves solely to convey the idea. | This truly liberated art from material constraints, expanding what 'art' could be and freeing artists from market pressures. |

| Dematerialization | Shift away from traditional, tangible art objects, embracing ephemeral forms like text, documentation, or actions. | It challenged the art market and traditional preservation, emphasizing the intellectual experience and a critique of commodification. |

| Language & Documentation | Often uses text, photographs, video, and records to articulate concepts and preserve ephemeral works, making the idea accessible. | It provided a direct means of communication, allowed for broad dissemination, and created a new kind of 'artifact' for non-physical art. |

| Viewer Engagement | Actively involves the audience in interpreting and completing the artwork through intellectual participation and critical thought. | This transformed passive viewing into active, co-creative participation, making art a dialogue and challenging viewers' assumptions. |

| Institutional Critique | Questions the structures and systems of the art world (galleries, museums, market), often through the artwork itself. | It forced us to re-evaluate art's context, power dynamics, and societal role, exposing the 'hidden levers' of influence. |

| Global Adaptability | Its idea-centric nature allowed it to be adapted to diverse cultural, social, and political contexts worldwide. | It demonstrated art's universal capacity for critical commentary and local relevance, transcending Western art historical narratives and serving as a powerful tool for political and social commentary. |

| Zen & Essence | A philosophical resonance with Zen, stripping away the superfluous to reveal the core idea and fostering a focus on essential meaning. | This offers a profound lens for understanding its depth beyond Western art history, aligning with my own artistic journey and the museum's philosophy. |

1. The Primacy of the Idea: The Brain is the Brush

Seriously, the idea is the artwork. The execution is just the most effective, and often simplest, manifestation of that idea. This is why you often see texts, maps, documents, or photographs as the "finished" piece. The artist wants you to engage with their thought process, their philosophical inquiry, not just admire their handiwork. The 'skill' here is intellectual agility and clarity of concept – the ability to formulate novel questions, synthesize disparate ideas, and articulate them with precision. It’s about the elegance of the thought, the sharpness of the question, or the audacity of the proposition. As an artist myself, I often find the initial conceptual spark the most challenging, and indeed, the most rewarding part of the entire creative process. For my own abstract work, it's about translating an idea or emotion into a visual language, where the thought itself guides the color and form. The audacity I speak of? It's the courage to say, "This idea is enough. This question is the art."

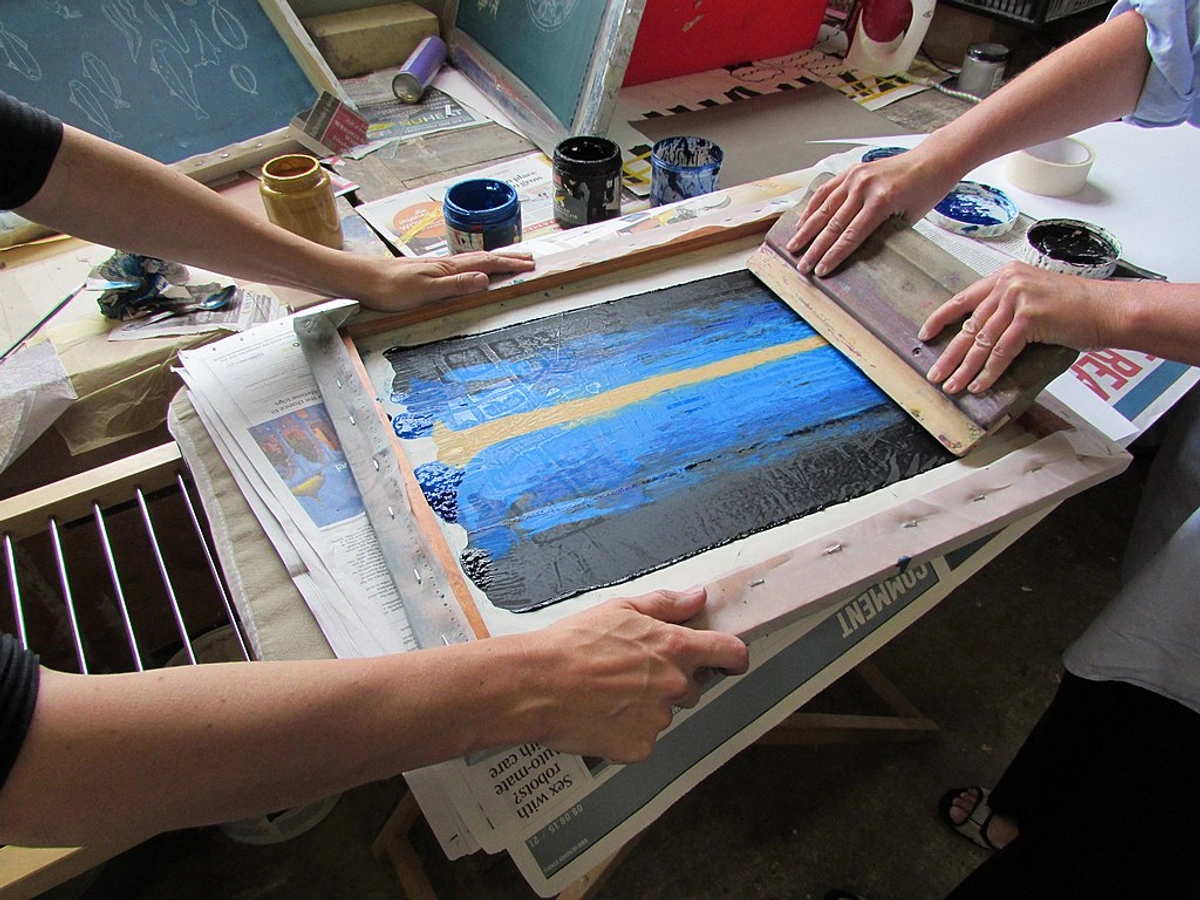

2. The Dematerialization of the Art Object & The Rise of Process Art

This is perhaps the most defining characteristic. For conceptual artists, the physical art object often becomes secondary, or even unnecessary. It’s about freeing art from its material constraints, from the expectation that it must be a painting, a sculpture, or a drawing. Instead of a meticulously carved sculpture, you might encounter Robert Barry's Inert Gas Series (1969), where the art is the release of invisible, odorless gas into the atmosphere, documented only by text and photographs. Or perhaps a certificate of ownership for a piece of invisible art, a simple instruction for an action, or even just a thought. This radical shift also presented immense challenges for the art market and institutions, raising complex questions about preservation, display, and ownership of non-physical or ephemeral (short-lived or temporary) works. The market, designed for tangible goods, found itself scrambling to define value when there was no 'thing' to collect. Galleries had to redefine their role, and collectors had to consider purchasing certificates or instructions rather than physical masterpieces. The paradox, of course, is that these ephemeral works often necessitated meticulous documentation (photos, videos, contracts, artist books) which then became a new kind of collectible 'art object' itself. Personally, I've had many discussions with gallerists about the perceived 'value' of a physical artwork versus the pure concept, and it's clear the market still grapples with this legacy. The most common struggle? Convincing a traditional collector that a piece of paper with instructions holds the same weight as a bronze sculpture.

This focus on the process of creation, rather than just the final product, led to the development of Process Art, a related movement where the materials and the actions of the artist were central, often emphasizing natural decay or transformation. For instance, Richard Serra's early works, with their piles of lead or thrown molten metal, emphasized the physical properties of materials and the process of their manipulation, rather than a finished form. Process Art, while sharing Conceptual Art's rejection of the static object, often foregrounds the tangible acts of making and material behavior, whereas Conceptual Art foregrounds the underlying idea that dictates those acts and their form, if any.

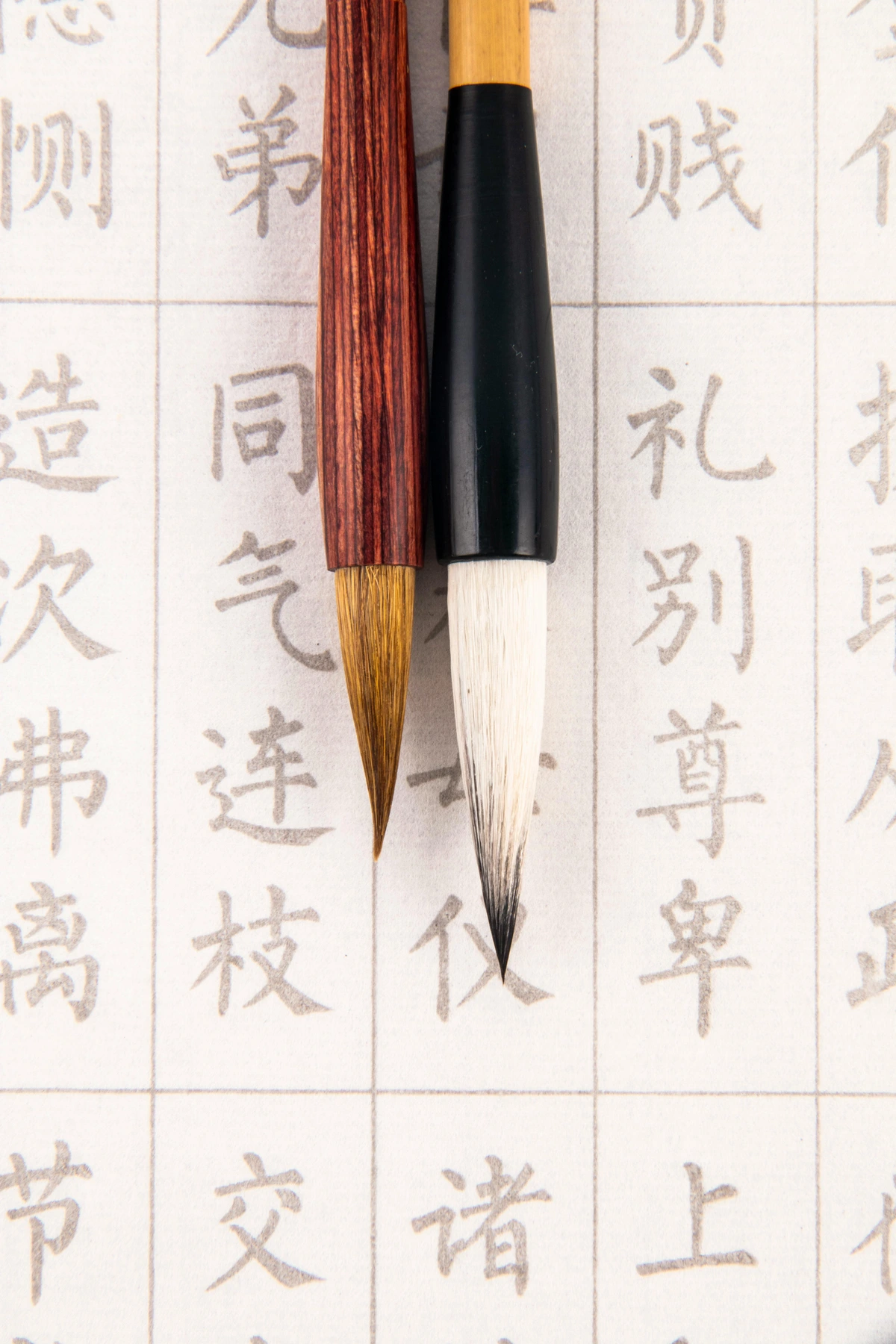

3. The Use of Text and Language: Words as Artistic Medium

Words become art. Artists used statements, definitions, instructions, and philosophical inquiries to convey their concepts. Sometimes, the artwork is the text itself. This is a very direct way of communicating the idea, leaving little room for purely aesthetic distraction, and emphasizing the analytical side of art. It’s a bit like a philosophical treatise but presented in an art context. This approach also extended to the phenomenon of artist books – artworks conceived and produced in book form, often self-published, allowing for broader dissemination of ideas outside traditional gallery systems. They became artworks in their own right, not just catalogues or explanatory texts, but a democratizing force, allowing art to bypass traditional gatekeepers and reach wider audiences. Think of Jenny Holzer's Truisms (1977-79), short, provocative statements like "Abuse of power comes as no surprise," presented on posters, plaques, or LED displays, where the text itself is the artwork, designed to confront the public directly with an idea.

4. Documentation as Art: Capturing the Ephemeral Thought

Given the dematerialization of the art object, meticulous documentation became crucial. Photographs, video, audio recordings, contracts, and detailed artist statements often served not merely as records, but as the primary artifact or even the artwork itself. This ensured the concept's survival and dissemination, allowing ephemeral works or pure ideas to be experienced and preserved, albeit indirectly, for future audiences. Imagine trying to explain Robert Barry's invisible gas without a photograph or a descriptive text – it simply wouldn't exist for most viewers. Documentation became the bridge between the fleeting idea and its enduring impact. It's the proof of a thought, a captured moment, a system made visible.

5. Audience Participation and Interpretation: You Complete the Art

This art often isn’t passively consumed. You, the viewer, are an active participant in completing the artwork through your intellectual engagement. Your thoughts, your interpretations, your questions – they're all part of the piece. The artist often provides a framework, but the meaning is often co-created in the viewer's mind. Think of Yoko Ono's instruction pieces, where the viewer's action or imagination is integral to the artwork. For example, her piece "Imagine a cloud" requires the viewer's mind to actively conjure the image, making their internal experience the artwork. Her iconic Cut Piece (1964) invited audience members to cut away pieces of her clothing, exploring vulnerability, trust, and the social dynamics of power and perception. It's not about what you see, but what you do or think. I recall one such piece, a simple set of instructions to find something beautiful in a mundane object; the act of searching, the shift in my own perception, that was the art. For my own abstract work, I often intentionally leave elements open, inviting you to project your own emotions or memories onto the canvas, completing the piece in your own unique way. What the artist intended might be one layer, but what you bring to it, your personal context and interpretation, often completes the conceptual circuit. It's a true dialogue, a challenge to your assumptions, and an invitation to become a co-creator.

6. Challenging Institutions and Conventions (Institutional Critique): The Art World Under Scrutiny

Conceptual artists were (and still are!) rebels. They questioned everything: the gallery system, the role of the critic, the very definition of who an artist is, and what constitutes a masterpiece. They wanted to democratize art, or at least force a re-evaluation of its established structures. This institutional critique (art that questions the very systems that display, sell, and interpret art) often took the form of works that exposed the mechanisms of the art world itself. This included art designed to be impossible to collect or sell, such as ephemeral actions or purely textual works, which directly undermined the commercial market's reliance on tangible objects. Some artists established artist-run spaces or alternative exhibition formats to bypass traditional gatekeepers entirely. Works that directly commented on museum practices (e.g., Hans Haacke's data-driven critiques of museum funding, like MoMA Poll which surveyed visitors on a political issue) also fall into this category. The art world's initial reception to these challenges was often one of suspicion or outright hostility; critics and curators, comfortable with established norms, found themselves confronted with works that deliberately sidestepped traditional criteria of aesthetic judgment and market value. Yet, over time, conceptual art's ideas permeated the very institutions it critiqued. Having navigated museum politics and funding applications myself, I can attest to the enduring power of art to expose the hidden levers of power and challenge us to look beyond the velvet ropes.

Other key figures in institutional critique include Andrea Fraser, whose performances often mimic museum tours or lectures, exposing the power structures and biases within art institutions. Fred Wilson's Mining the Museum (1992) rearranged historical collections to reveal hidden narratives of race and class, forcing viewers to confront the biases of museum display. And of course, the anonymous feminist collective Guerrilla Girls famously used posters and protest art to highlight sexism and racism in the art world, directly challenging major institutions. Their aim was often to circumvent the commercial art market, or at least force it to confront its own values and power dynamics. The economic impact of this dematerialization was profound, challenging galleries and collectors to redefine value beyond the tangible object. Contemporary artists like Ai Weiwei continue this legacy, using conceptual strategies to critique political power and global systems, as seen in his large-scale installations and projects that often involve the public directly. It reminded me a bit of the playful disruption that Surrealism and Dadaism brought, but with a more intellectual, less dream-like edge.

7. Global & Diverse Expressions: Beyond Western Narratives

While often associated with Western Europe and North America, Conceptual Art's tenets resonated globally because its focus on ideas made it incredibly adaptable. Artists in various regions used conceptual strategies to address local political, social, and cultural contexts. In Latin America, artists like Cildo Meireles created works that critically engaged with political censorship and consumerism (e.g., his Insertions into Ideological Circuits, 1970, involved meticulously modifying circulating currency or Coca-Cola bottles with political messages, then ingeniously returning them to circulation, thus embedding critique within everyday systems). In the UK, the Art & Language group pushed the boundaries of collaborative, text-based conceptual art, often producing philosophical essays and complex linguistic puzzles as their artworks, effectively making critical theory itself a form of art. Beyond these, artists in Africa, Asia, and Oceania adapted conceptual strategies to local historical narratives, post-colonial critiques, and indigenous knowledge systems, creating powerful works that challenged dominant art historical narratives and asserted diverse cultural perspectives. For instance, the Japanese Gutai group (active from the mid-1950s) created performance-based works and emphasized process and material interaction that foreshadowed many conceptual practices, focusing on the freedom of the individual spirit and the relationship between body, matter, and space. In India, artists like Subodh Gupta use everyday objects in large-scale installations to explore themes of consumerism, migration, and the cultural landscape of contemporary India, employing conceptual strategies to infuse local context with universal commentary. And in South Africa, artists like William Kentridge (though often associated with drawing and animation) employ conceptual frameworks to explore colonial history, apartheid, and post-apartheid realities through his highly intellectual and formally diverse works. The universality of an 'idea' as the core art allowed for diverse, localized expressions far beyond a singular stylistic approach, proving art's incredible versatility. I'm always amazed by how a simple concept can bridge vast cultural divides and speak to local truths.

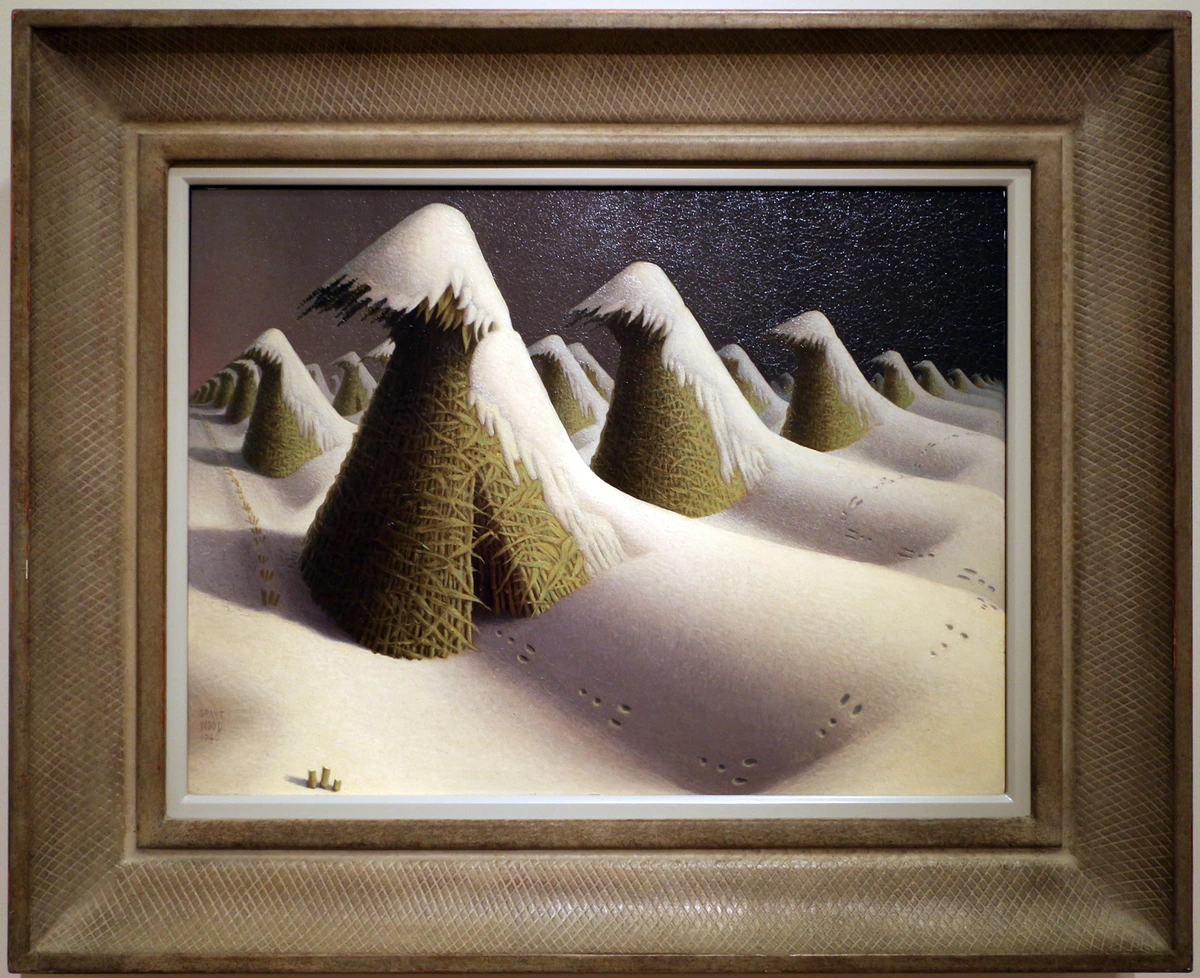

8. Zen & The Stripping Away: Finding Essence in Concept

Given the name "Zenmuseum," it feels only right to draw a parallel. For me, there’s a profound connection between the principles of Conceptual Art and Zen philosophy. Both advocate for stripping away the superfluous to reveal the essence. Just as Zen seeks enlightenment through direct experience and a focus on the present moment, free from material attachment (concepts like sunyata or emptiness – not as nothingness but as interconnectedness and lack of inherent self; wabi-sabi, the beauty in imperfection and impermanence; or even mu, meaning "nothingness" or "emptiness" in a way that points to the ultimate reality beyond conceptual distinctions), Conceptual Art seeks truth through the pure idea, unburdened by material form or traditional aesthetic expectations. It's about perception, mindfulness, and the profound meaning found in simplicity – an idea, a gesture, a fleeting moment. This approach, to truly focus on the core meaning, is something I strive for in my own abstract work, even with vibrant colors. For example, an artwork I created that involved simply arranging a few found river stones on a canvas aimed to evoke a feeling of transient beauty and the interconnectedness of nature, much like a carefully composed Zen garden. The essence, the underlying truth, is always paramount, guiding my brushstrokes and compositions, echoing Zen's emphasis on finding profound meaning in the direct experience of the essential. It’s an aesthetic of pure thought, much like the quiet contemplation of a Zen garden, where the arrangement of a few stones conveys a universe.

Exploring Key Works and Influential Artists: The Architects of Thought

While the seeds of Conceptual Art were sown earlier, a new generation of artists emerged, solidifying its principles and pushing its boundaries. These are the architects of thought who shaped the movement, often through pivotal exhibitions that served as manifestos in themselves, bringing these radical, idea-driven practices to wider public attention. They were the ones who dared to ask, "What else can art be?"

Seminal Exhibitions and Their Impact

Two exhibitions, in particular, solidified the movement's presence and fundamentally shifted how art was perceived:

- "When Attitudes Become Form: Works – Concepts – Processes – Situations – Information" (1969, Kunsthalle Bern): Curated by Harald Szeemann, this exhibition was a revolutionary moment. It brought together artists who were pushing boundaries with ephemeral, process-based, and idea-driven works, often created on-site. It showcased the raw energy of what would become Conceptual Art, emphasizing the artist's process and conceptual intent over the finished product. Crucially, it forced critics and institutions to confront new definitions of artistic value, moving beyond the physical object and into the realm of ideas and actions, laying the groundwork for how galleries would engage with non-traditional art. Critics were often bewildered, but the art world was forced to confront new definitions of value, and artists felt a surge of liberation. It was a true watershed moment.

- "Art by Telephone" (1969, Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago): This exhibition featured artworks created solely through verbal instructions given over the phone, with the recipient (often museum staff) executing the piece. This radical approach directly demonstrated the primacy of the idea over the physical object and challenged traditional notions of art creation, authorship, and display. The instructions themselves became the art, not the subsequent physical manifestation, proving that a concept could travel across distances and hands, yet retain its artistic core. It specifically challenged gallery practices by requiring staff to become active participants in the art's creation, blurring the lines of traditional roles. I remember hearing whispers that some critics scoffed, calling it a mere parlor trick, but the exhibition proved its point: the conceptual spark was enough, even if only conveyed by a voice on the other end of the line.

The Pioneers of Thought

- Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968): The Mischievous Ancestor

- Contribution: His "readymades" fundamentally questioned what constitutes art and who decides it. Fountain (1917) challenged aesthetic values and elevated the artist's conceptual choice. He shifted the focus from the artist's hand to the artist's mind, arguing that the mere act of selecting and naming an object as art was a sufficient creative act. His Bottle Rack (1914) further solidified this, turning a functional object into art by intellectual decree. Duchamp's work exemplifies the Primacy of the Idea and Institutional Critique by demonstrating that artistic value could be imposed by the artist and validated by the institution, rather than inherent in craftsmanship.

- My Take: Duchamp was like the cool older sibling who broke all the rules, clearing the way for generations to come. He taught us that the frame of art matters more than what's in it, sometimes. It’s an audacious move that still makes curators sweat trying to explain it, but it's foundational. His irreverence was, in itself, a profound conceptual statement.

- Joseph Kosuth (b. 1945): The Linguistic Philosopher

- Contribution: His seminal work, One and Three Chairs (1965), presents a real wooden chair, a photograph of that exact chair, and the dictionary definition of "chair." It's a profound linguistic and philosophical inquiry into representation and language itself. He focused on tautologies – statements true by virtue of their meaning, using art to explore the very structure of meaning. He famously asserted, "The value of particular artists after Duchamp can be weighed according to how much they questioned the nature of art." Kosuth’s work brilliantly illustrates the Use of Text and Language as art and the Primacy of the Idea, pushing the viewer to analyze how meaning is constructed.

- My Take: My first encounter with One and Three Chairs left me feeling like I was being asked a riddle: Which is the "art"? All of them, and none of them, simultaneously. It’s a puzzle, but a genuinely rewarding one that shifted my perspective entirely, showing how language frames our reality. It's art that makes you aware of how you make meaning.

- Sol LeWitt (1928-2007): The Master of Instructions

- Contribution: His Paragraphs on Conceptual Art (1967) and Sentences on Conceptual Art (1969) became veritable manifestos. He famously stated, "The idea itself, even if not made visual, is as much a work of art as any finished product." His renowned wall drawings, often executed by assistants following his precise instructions, perfectly embody the idea taking precedence over the artist's hand or individual style. The act of creation becomes an intellectual command, a meticulously planned process, not a physical gesture. LeWitt’s practice is the epitome of Art as Potential: Instructions and Scores and the Dematerialization of the Art Object through its emphasis on the reproducible idea.

- My Take: This overlaps beautifully with the ideas explored in Minimalism, where simplicity and the viewer's experience are paramount. However, Minimalism often focuses on the experience of the object, while Conceptual Art pushes further into the realm of the experience of the idea. LeWitt showed that the blueprint can be the masterpiece, and that an artwork's existence can be independent of its maker's direct touch. I find his approach incredibly liberating, proving that the concept has its own inherent power, regardless of who puts brush to wall.

- On Kawara (1932-2014): Time as Medium

- Contribution: Famous for his "Date Paintings" (simple canvases stating the date of their creation, only counting if completed on that day) and "I Am Still Alive" telegrams, meticulously documenting the passage of time and his own existence. He made time and existence themselves the subject of his art, relying on systems and documentation. Kawara's methodical approach embodies the Structuring Thought: Mapping, Archiving, and Systematization principle, using consistent systems to explore profound existential concepts.

- My Take: I find Kawara's work deeply contemplative, almost Zen-like in its repetitive focus on the present moment and the stark reality of time's passage. It's an existential whisper, not a shout, reminding us of our own fleeting existence through simple, undeniable facts. It's art that forces you to confront your own mortality, quietly, powerfully.

- Allan Kaprow (1927-2006): The Pioneer of Happenings

- Contribution: Credited with coining "Happenings" – a precursor to performance art, these were loosely structured events and performances where the emphasis was on the action, the experience, and audience participation rather than a created object. His 18 Happenings in 6 Parts (1959) involved viewers following instructions, moving, speaking, and interacting, directly dismantling the traditional art experience and pushing the boundaries of art into everyday life. Kaprow's Happenings are a prime example of Audience Participation and Interpretation, making the viewer's direct experience and interaction central to the artwork.

- My Take: Kaprow truly understood the power of experience. He didn't just want you to look; he wanted you to be there, to participate, to live the art. That's a profound shift, moving from passive observation to active engagement and blurring the lines between art and life itself. I often think about how much courage it must have taken to ask people to literally become the art.

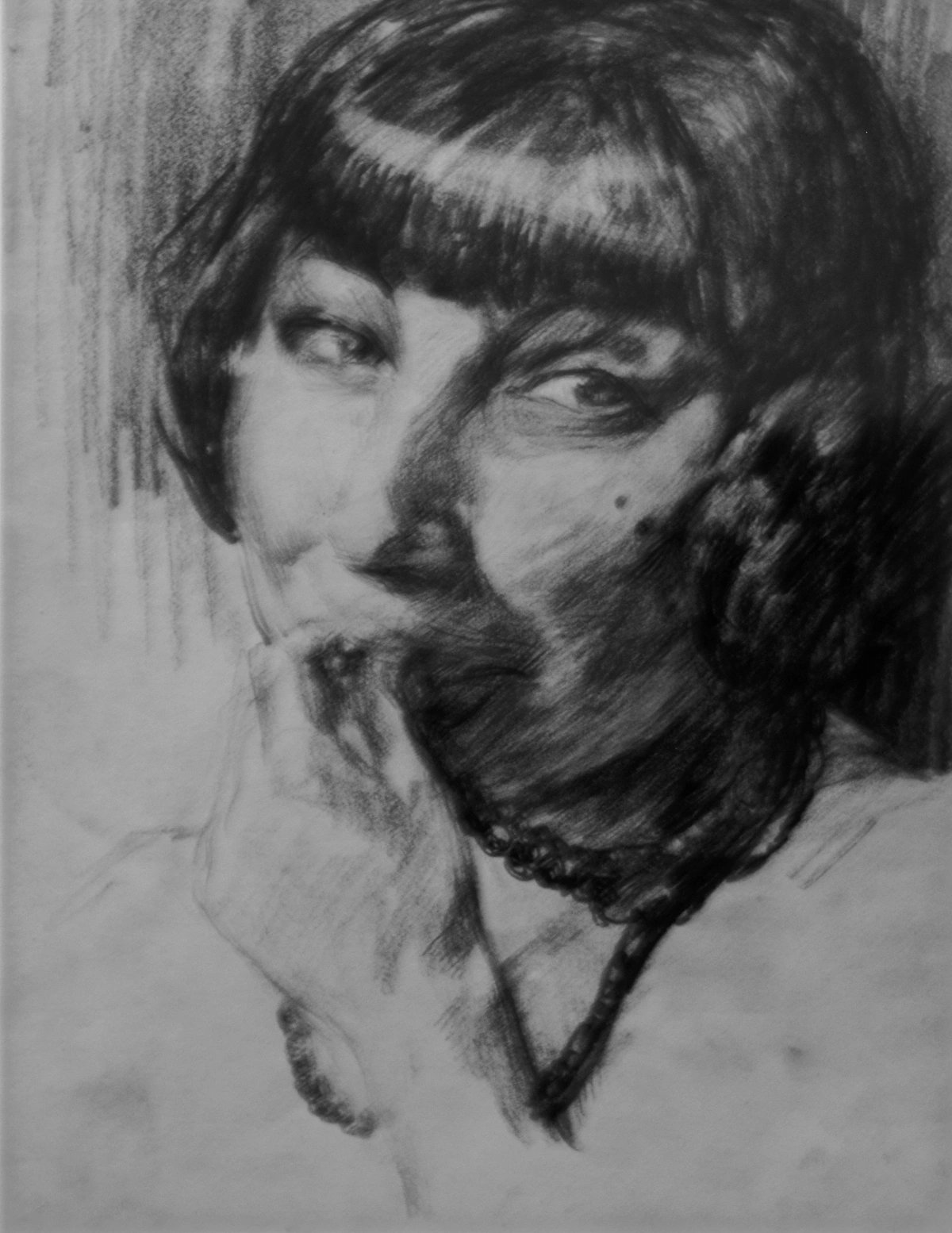

- Adrian Piper (b. 1948): Concept as Critique & Confrontation

- Contribution: A philosopher and artist, Piper used conceptual strategies, often involving text, performance, and self-portraits, to explore themes of race, gender, identity, and social prejudice. Her work frequently directly engaged the viewer in uncomfortable self-reflection, making the conceptual encounter a political and personal one. She forced audiences to confront their own biases through her work like Catalysis (1970-1971), where she performed unsettling actions in public spaces. Piper's work powerfully enacts Viewer Engagement and Institutional Critique, forcing audiences into uncomfortable self-reflection and challenging societal norms.

- My Take: Piper's work is intellectually rigorous and unflinchingly direct. It's art that doesn't just ask questions, but demands answers, often from you, the viewer, about your own biases and assumptions. That's powerful art, designed to make you think and, hopefully, act differently. I've personally found her work to be a challenging mirror, forcing me to examine my own positions and privileges.

Other Significant Figures who Shaped the Conceptual Landscape:

- Lawrence Weiner: Known for his "declarations" of intent, often painted directly on walls. His art often consisted of text describing materials or actions, for example: "A REMOVAL OF L. 3 MANGANESE FROM A CHEMICAL BASE, 2. A REMOVAL OF L. 3 MANGANESE FROM A GEOLOGICAL BASE, 3. A REMOVAL OF L. 3 MANGANESE FROM A BIOLOGICAL BASE." He challenged the art market by declaring that his works could exist purely as text, regardless of physical manifestation. It's a testament to the power of pure statement.

- Yoko Ono: Her instruction pieces, like Cut Piece, invited audience interaction and explored ephemeral ideas of vulnerability and human connection, blurring the lines between art and life. They required the viewer's action or imagination to be complete, making art a truly collaborative mental exercise.

- John Baldessari: Employed photography, text, and appropriated imagery to question authorship, meaning, and the function of art education, often with a wry sense of humor. He used images not for their aesthetic beauty, but as intellectual propositions, famously destroying all his early paintings and beginning again conceptually. His work often feels like a visual riddle that makes you smile while you think.

- Bruce Nauman: Utilized his own body, language, and everyday materials in performances and installations to explore human experience, perception, and the nature of the artistic process. His work often felt like a philosophical experiment, a direct inquiry into the conditions of existence.

- Hanne Darboven: Her meticulously structured, often repetitive, text-based works explored systems of time, mathematics, and writing itself as art. It’s a methodical, almost meditative approach to concept.

- Felix Gonzalez-Torres: His piles of candy and stacks of paper invited viewer interaction and disappearance, embodying themes of loss and memory. These works deliberately challenged traditional notions of ownership and permanence, as the art literally diminished over time, requiring replenishment and re-installation, making the concept of renewal, absence, and connection central. They are poignant and deeply human conceptual works.

- Jenny Holzer: Known for her powerful LED text installations that challenge public spaces with provocative statements (e.g., Truisms), forcing audiences to confront societal and political clichés in unexpected contexts. She turns public spaces into canvases for direct, thought-provoking ideas.

- Ai Weiwei: A contemporary master who uses conceptual approaches to political and social commentary, often leveraging readymades, performance, and documentation in his activism. His Fairytale (2007), bringing 1001 Chinese citizens to Documenta, is a powerful example of using human participation as a conceptual artwork and a critique of global systems. He shows that ideas can be incredibly impactful and global in scale.

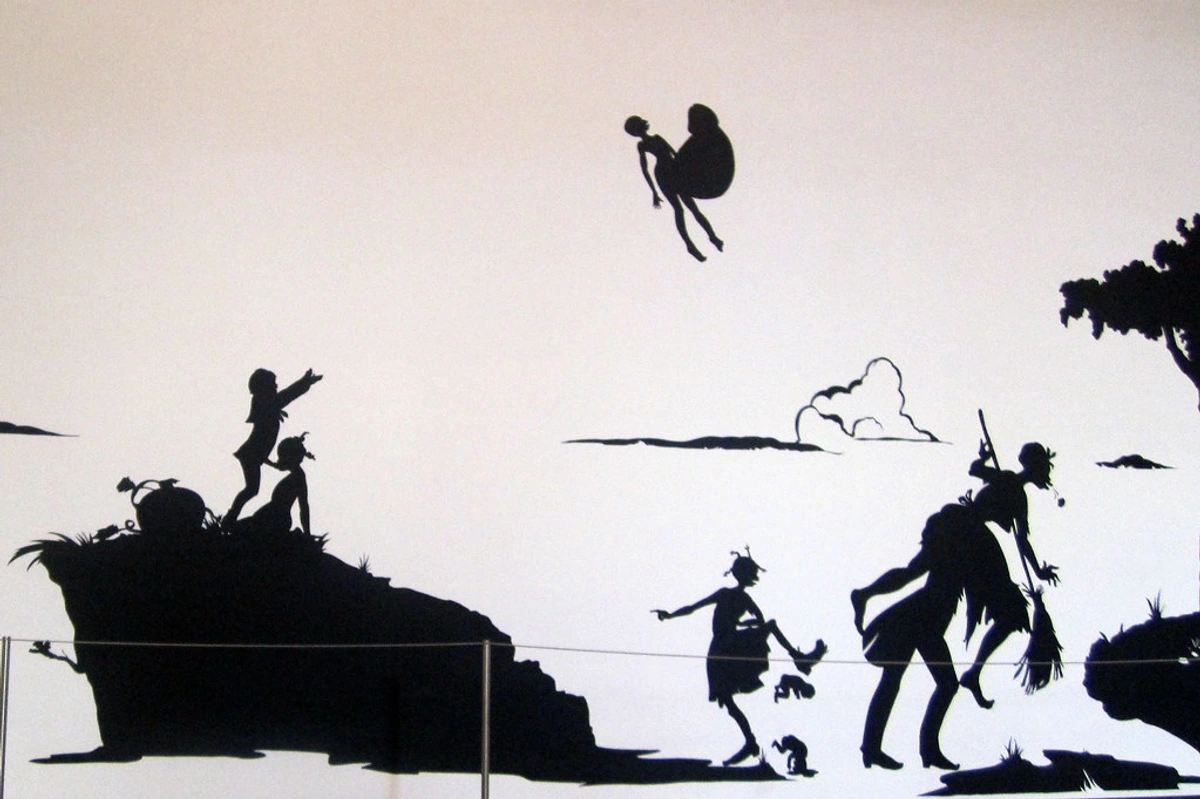

By the way, if you're interested in artists who use powerful, often conceptual narratives in their work, I highly recommend exploring the works of Kara Walker. Her use of silhouettes and historical context is incredibly thought-provoking and emotionally resonant, a contemporary master of narrative through conceptual means.

Common Conceptual Strategies and Techniques: The Artist's Toolkit

Conceptual artists aren't just thinking; they're actively deploying a toolkit of strategies to bring their ideas to life. From my curator's perspective, understanding these methods is key to appreciating the ingenuity behind the often unassuming final works. These aren't mere stylistic choices; they are deliberate actions designed to make the idea tangible, to question, and to provoke.

1. Challenging Authorship & Originality: Appropriation and Recontextualization

This involves taking existing objects, images, or texts and placing them in a new context to imbue them with altered or new meaning. It fundamentally challenges notions of originality, authorship, and the inherent value of an object. Artists like Sherrie Levine famously re-photographed works by male masters, questioning concepts of originality, the male gaze in art history, and the very act of artistic creation. Richard Prince similarly re-photographed advertisements, particularly Marlboro cowboys, to comment on consumerism and iconic American imagery, turning mass media into artistic critique. Appropriation was potent because it allowed artists to critique power structures, challenge copyright, and democratize art by asserting that meaning could be derived from context, not just from original creation. Legally and ethically, this often skirts a fine line, raising complex questions about fair use, intellectual property, and what constitutes a transformative work – a debate that continues to evolve today. It’s a bit like a cultural remix, where the new arrangement creates new meanings.

2. Art as Declaration: Artist Statements and Manifestos

Far from just explanatory texts, for conceptual artists, statements and manifestos often become integral parts of the artwork itself. They articulate the core concept, guide interpretation, or even function as the primary artistic output, elevating intellectual declaration to the status of art. In some cases, the manifesto itself was the art, functioning as a conceptual artifact that provided instructions, a philosophical stance, or simply a declaration of artistic intent, demanding to be read and engaged with as a piece in its own right. It’s the artist saying, "My words are the art." You can explore this further in the art of the artist statement.

3. Art as Potential: Instructions and Scores

Many conceptual works exist as a set of instructions or a "score" for an action that may or may not be executed. The idea, the potential for realization, is the art. Sol LeWitt's wall drawings, as we'll see, are perhaps the quintessential example, where the art resides in the instructions, not in any single physical manifestation. Yoko Ono's instruction pieces similarly rely on the viewer's mental or physical execution of a simple command. The purpose of these instructions was often to decentralize the artist's role, democratize art creation, and emphasize the idea's permanence and reproducibility over a singular, precious object. The concept could be re-performed or recreated infinitely, maintaining its conceptual integrity regardless of specific execution. It allows the idea to live beyond the artist’s direct hand.

4. Structuring Thought: Mapping, Archiving, and Systematization

Artists frequently use systems, maps, and archival practices to explore concepts related to information, classification, space, and time. This can involve meticulous categorization, data collection, or the creation of complex diagrams that represent an idea, making the organization of knowledge itself a form of artistic expression. Artists might use these techniques to explore concepts like entropy (the gradual decline into disorder), the fallibility of memory, information overload, or the invisible social and political structures that govern our lives. Think of intricate diagrams detailing a system, or vast collections of seemingly mundane data presented as art. It's about turning information into insight.

5. Immersive Ideas: Installation Art (Conceptual Aspect)

While not exclusively conceptual, many installations are fundamentally idea-driven. They transform a space, creating immersive environments that engage the viewer intellectually as much as physically. The concept often dictates the materials, arrangement, and viewer's experience, making the entire environment a vehicle for a particular thought or inquiry. For instance, an installation might use sound, light, and found objects to explore themes of displacement, or an artist might arrange seemingly disparate objects to create a dialogue about consumerism. The space itself becomes a canvas for the idea.

Conceptual Art Today: The Legacy of Ideas in the 21st Century

Conceptual Art didn't disappear after the 70s; it utterly permeated the art world, becoming a foundational language for much of what we call contemporary art. This era also saw the emergence of Post-Conceptual Art, where artists built upon conceptual strategies, often reintroducing elements of aesthetics or materiality but always underpinned by a strong conceptual framework. Post-Conceptual artists, rather than rejecting the object entirely, often use conceptual strategies to imbue objects, images, or performances with deeper intellectual content, creating works that are both visually engaging and conceptually rigorous. Think of artists like Jeff Koons or Cindy Sherman. Koons' polished, often monumental sculptures of everyday objects are intensely conceptual, commenting on consumerism and pop culture, while his high-gloss finish reintroduces a powerful, almost seductive aesthetic. Sherman's Untitled Film Stills use photography to explore identity and representation through staged self-portraits mimicking cinematic clichés, proving that a strong conceptual idea can thrive even with traditional media and a keen eye for visual impact. While 'pure' conceptual art might prioritize the idea to the exclusion of all else, Post-Conceptual art often marries intellectual rigor with a renewed attention to visual impact and material presence – a powerful synthesis.

Today, its influence is everywhere. Many artists, myself included, operating in abstraction, are deeply concerned with the underlying concepts, the feeling, the why behind the brushstroke, or the arrangement of colors. It’s not just about creating something visually pleasing; it’s about evoking a thought, an emotion, a question, or a specific conceptual framework. This liberation allows artists immense freedom to explore complex themes without being constrained by traditional media or techniques. Perhaps that's why you see so much abstract expressionism and pop art (think of Andy Warhol's soup cans – an ordinary object elevated by a conceptual frame) often engaging with conceptual undercurrents.

Its principles are particularly relevant in the age of digital art and NFTs, where the concept, the smart contract, or the unique digital identifier often holds more 'value' and 'presence' than any physical object. The dematerialization that began in the 60s has found new, powerful expressions in the virtual realm. The smart contract underlying an NFT, for instance, acts as the definitive 'instruction set' or 'concept' that defines ownership and unique characteristics, mirroring conceptual art's embrace of non-physical frameworks as the artwork itself. Beyond this, the provenance and digital scarcity inherent in NFTs are themselves conceptual constructs, asserting unique value to a digital asset that could otherwise be infinitely replicated. It reminds us that art can thrive beyond physical boundaries, asking us to redefine ownership and permanence. It’s a fascinating, logical evolution of the conceptual premise.

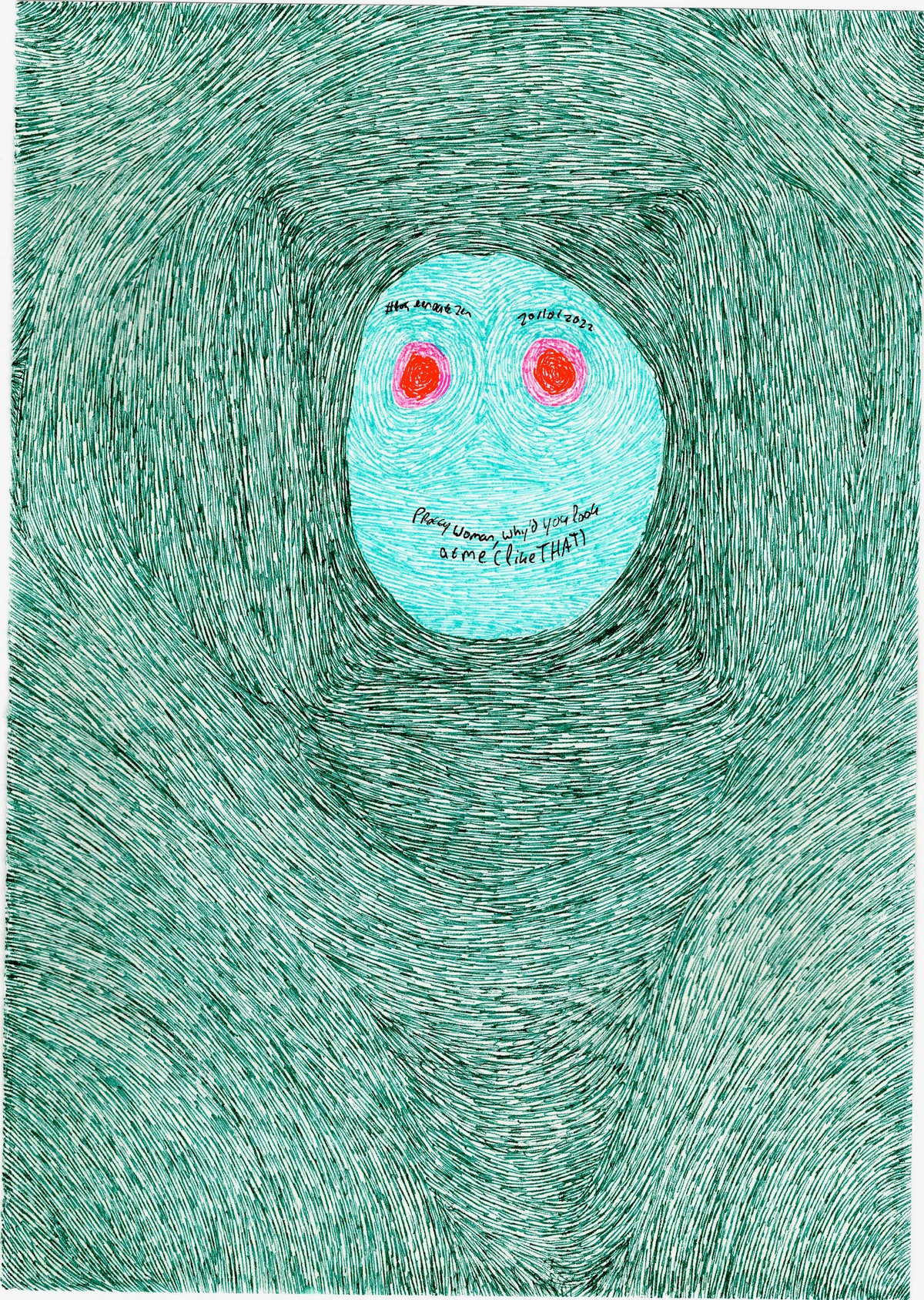

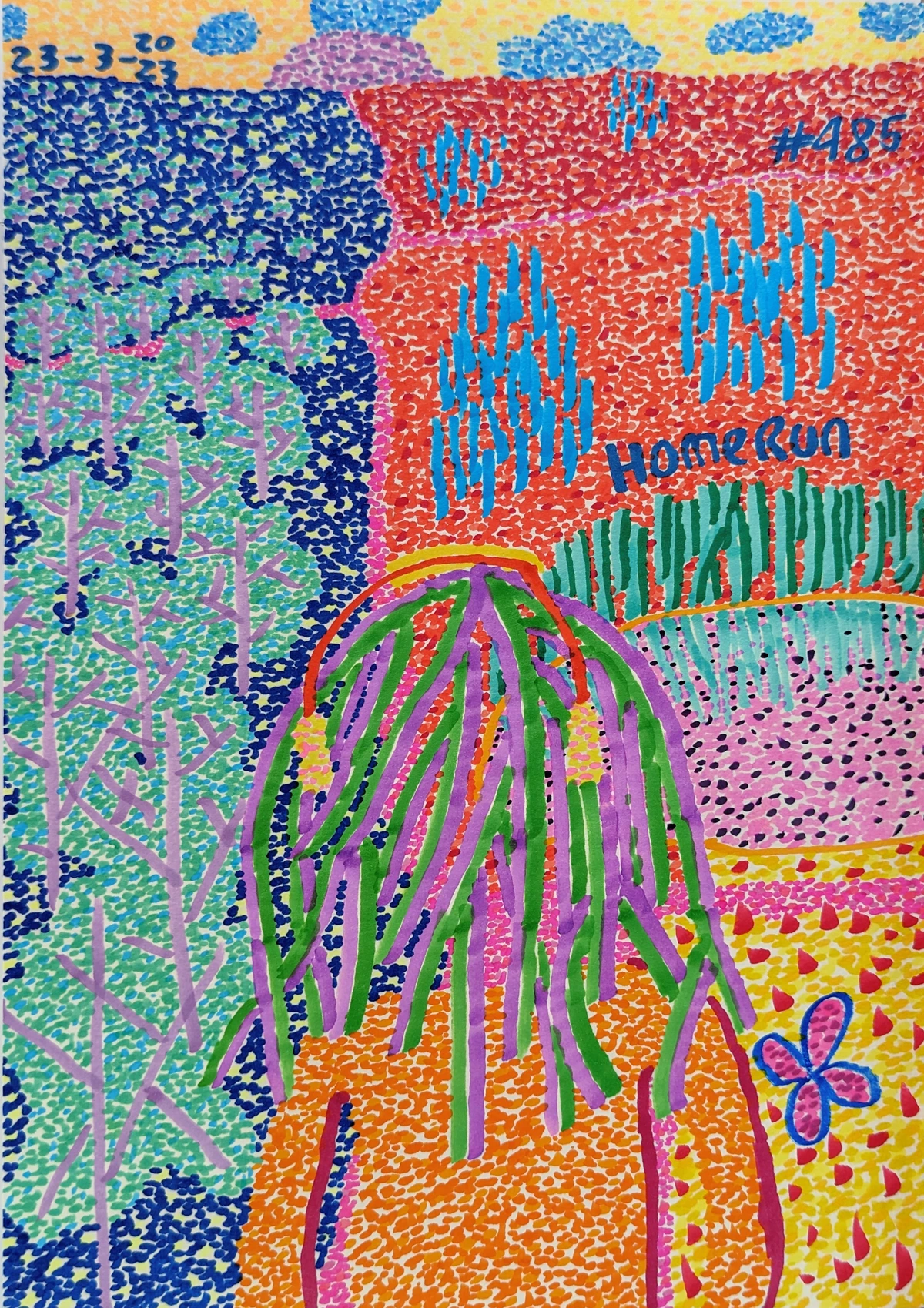

For my own work at Zen Dageraad Visser's Museum in Den Bosch, the ideas behind the vivid colors and abstract forms are as important as the forms themselves. It’s about translating emotions and philosophical inquiries into visual language, allowing the viewer to complete the narrative. Conceptual art gave me permission to move beyond purely aesthetic concerns, allowing the core idea to dictate the form, the palette, the texture. This liberation has been foundational to my artistic voice. If you're curious about the ongoing conversation between concept and creation, I invite you to explore my latest works available for purchase at /buy or trace my artistic evolution on the /timeline. Much of what I create aims to evoke a specific thought or feeling, to engage the viewer's intellect as much as their eyes, a direct legacy of the conceptual revolution.

Common Misconceptions & Criticisms: Addressing the Elephant in the Gallery

"My kid could do that!" or "That's not art!" — sound familiar? I’ve heard it countless times, and honestly, sometimes a small, mischievous part of me agrees with the sentiment before the curator in me kicks in. Conceptual Art does challenge our ingrained notions of what art should be, and that's precisely its point. Let's tackle a few common critiques:

"It's pretentious and inaccessible."

I get it. I really do. I remember walking into a gallery once, expecting a grand masterpiece, and finding nothing but a handwritten note on a wall. My first thought was an eye-roll. But I've learned that if you walk into a gallery expecting a beautiful painting and find a pile of bricks (or a typed statement), it can certainly feel like a joke at your expense. However, the intent isn't to be pretentious, but to provoke thought and critical engagement. The perceived inaccessibility often comes from a lack of context. Once you understand the question the artist is asking, the intellectual framework they're operating within, the piece often clicks into place. It asks for intellectual effort, which can be exhausting, but I promise you, it's profoundly rewarding. It's less about a superficial visual experience and more about a deep mental one. It's like learning a new language – challenging at first, but incredibly enriching once you grasp its grammar and vocabulary. I felt that challenge myself when trying to appreciate early Fluxus works; it took time to learn their particular "grammar" of absurd gestures. Consider Carl Andre's Equivalent VIII (1966), a stack of 120 firebricks arranged in a rectangular block. Without understanding his minimalist and conceptual approach to sculpture – that the object's simple, physical presence, its material, and its direct relationship to the floor is the artwork – it might just seem like a pile of bricks. But once contextualized, it becomes a profound statement on form, space, and the essence of sculpture, forcing us to rethink the very definition of a 'monument' or 'sculpture.'

"Anyone could have thought of that."

Perhaps, but they didn't, did they? The brilliance in Conceptual Art often lies in the originality of the idea, the audacity to present it, and the intellectual rigor behind its articulation. It's like saying "anyone could have discovered gravity." True, the apple would have fallen for anyone, but Newton formulated the law and articulated the underlying principles. Conceptual art is about that initial conceptual leap, that audacious first move, and the clear articulation of a novel thought, not just a raw observation. It's the moment of insight, not the obviousness in hindsight, that truly matters. This also touches on the strategy of appropriation, where artists recontextualize existing objects or images to imbue them with new meaning, challenging notions of originality and authorship. It's the difference between seeing a urinal and seeing Fountain. The intellectual act of framing the question or idea is the art.

"It lacks skill or craftsmanship."

This is a big one. And yes, many conceptual pieces deliberately eschew traditional artistic skill. But this isn't because the artists can't draw or paint; it's a conscious decision to shift focus. I've seen countless conceptual artists with impeccable drawing skills choose not to use them in a particular work because the idea demanded a different approach. The skill here is intellectual: the ability to conceive, articulate, and present a compelling, often complex, idea in its most distilled form. Sometimes, the craftsmanship is in the precise execution of a simple instruction, the clarity of a written statement, or the meticulous documentation of an ephemeral event. The skill simply resides in a different realm, demanding mental dexterity rather than manual dexterity. For instance, in my own journey, I often find myself deliberately simplifying forms or using unconventional materials precisely because the underlying concept is so strong, it doesn't need additional visual ornamentation; the idea itself carries the weight. It's not about being lazy; it's about being strategic.

"It lacks emotional depth."

This is a common, and understandable, concern. If you're used to art that tugs at your heartstrings through vivid depictions of human struggle or breathtaking beauty, a purely textual piece might feel cold. However, Conceptual Art can evoke incredibly powerful emotions, but often through intellectual engagement and resonance rather than immediate visual pathos. The feeling comes from the insight it provokes, the deep questions it unearths, or the uncomfortable truths it reveals. A piece that challenges your biases, makes you question your reality, or brings a sudden, profound realization can be emotionally overwhelming, even if it's just a word on a wall. The emotion is often a delayed reaction, a slow burn of understanding that settles deep within you, changing how you perceive the world long after you've left the gallery.

"It's ephemeral and will disappear."

Indeed, many conceptual works are intentionally ephemeral, existing only for a short time or as a series of actions. This is often a deliberate critique of art's commodity status and permanence. However, this doesn't mean the idea disappears. Conceptual artists meticulously document their works through photographs, videos, written accounts, or certificates of authenticity. This documentation often becomes the enduring artifact, allowing the concept to live on and be re-performed or re-imagined by future audiences. It's the enduring thought, not the fleeting physical manifestation, that holds the power.

How to Engage with Conceptual Art: A Curator's Advice

So, how do you approach a work of Conceptual Art without feeling lost? My advice is simple, born from years of wrestling with these very questions:

- 1. Consider the context provided by the label, thoroughly. The artist's statement or accompanying text is often crucial. It's not just a caption; it's an integral part of the artwork itself, providing the essential context for the idea. Think of Joseph Kosuth's One and Three Chairs; without reading the dictionary definition, you're missing a critical piece of the puzzle that unlocks the entire concept.

- 2. Ask "Why?" not "What is it?" Instead of trying to identify an object or interpret a scene, try to understand the artist's intent, the question they're posing, or the comment they're making about art, society, or philosophy. Why this object? Why this text? Why this action? The artwork is often the answer to a question, or the question itself. This shifts your engagement from passive observation to active inquiry, challenging your intellectual curiosity.

- 3. Don't look for beauty in the traditional sense. Instead, look for a different kind of beauty – the intellectual elegance, conceptual wit, philosophical depth, or even a profound challenge to your own assumptions. Beauty here is in the idea, the insight, the spark it ignites in your mind. It’s an aesthetic of thought, a moment of profound revelation rather than superficial pleasure.

- 4. Embrace the discomfort. If a piece makes you uncomfortable, confused, or even angry, that's often part of the experience. It means it's successfully challenging your perceptions and pushing you to think differently, and that, in itself, is a valuable artistic interaction! It's an invitation to grow, to expand your intellectual horizons, and to challenge your own preconceived notions of what art should be.

- 5. Accept ambiguity. Sometimes, there isn't one single "correct" interpretation, and that's precisely the point. The artwork might be designed to open up multiple readings, to spark debate, or to highlight the subjective nature of meaning. Embracing this ambiguity allows for richer, more personal engagement with the piece.

- 6. Research the context. Knowing a bit about the artist's background, the historical moment, or the philosophical trends influencing the work can unlock layers of meaning. Context is king in conceptual art, providing the intellectual scaffolding for understanding.

- 7. Talk about it. Share your thoughts, your frustrations, and your insights with others. Dialogue is often where the deeper understanding emerges, where different perspectives illuminate the work. It's why art galleries are such fantastic places for discussion, aren't they? Debate and discussion are part of the art itself.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) on Conceptual Art: Your Lingering Questions, Answered

To further clarify any lingering questions, here are some common queries I often encounter about Conceptual Art, offering my perspective as an artist and curator, aiming to provide comprehensive answers.

Q1: What's the difference between Conceptual Art and Abstract Art?

Ah, a classic! This is where many get tangled. From my perspective as an artist, Conceptual Art prioritizes the idea above all else, often minimizing or even eliminating the physical object. The visual form, if it exists, is just a vessel for the concept, and its aesthetic qualities are secondary. Imagine a meticulously written instruction for a painting – the instruction is the art, not the potential painting itself. Abstract Art, on the other hand, deals with visual elements like color, form, line, and texture, often to express emotions or non-representational ideas, but the visual experience of the artwork itself remains central. It's still very much about what you see and feel directly from the visual. Think of a vibrant Wassily Kandinsky painting versus a typed instruction sheet by Sol LeWitt. Both are non-representational, but their core intentions and modes of engagement differ significantly. You can dive deeper into the nuances of this distinction with this excellent article on the definitive guide to the history of abstract art: key movements, artists, and evolution.

Q2: Is all modern art conceptual?

Not at all! While Conceptual Art has profoundly influenced much of contemporary art, many modern artists still create works where aesthetics, technique, or emotional expression are paramount. It's more accurate to say that conceptual strategies are often employed within a wider range of modern artistic practices, but not all modern art is purely conceptual. The lines between movements can be blurry, and you'll find exciting crossovers. To understand this better, you might want to read about modern vs. contemporary art.

Q3: Why is Conceptual Art important?

Its importance, to my mind, lies in its ability to expand our understanding of what art can be. It radically challenged the art market, questioned authorship, and broadened the very definition of creativity. It forced us to think, to engage intellectually, and to recognize that profundity can exist in the most unexpected and dematerialized forms. It’s less about a new style and more about a new way of thinking about art and its role in society, offering immense freedom to artists. It changed the game, showing us that the most powerful art might be the one you can't even hold.

Q4: How is Conceptual Art created?

There's no single "how-to" guide, which is part of its charm! It usually begins with an artist formulating a precise idea, question, or statement. The creation then involves selecting the most effective (and often simplest) means to convey that idea. This could be writing a text, documenting an action or performance (like Yoko Ono's Cut Piece), commissioning an object (that someone else makes, as with some LeWitt works), or even creating a temporary installation. Sometimes, artists collaborate or work with entire communities to bring a concept to life, making the collective experience the art. The process of bringing the idea to fruition, even if that process is minimal, becomes an integral part of the art, often involving extensive research and critical thought. The artist's hand may be absent, but their mind is undeniably present, meticulously orchestrating the conceptual encounter.

Q5: Can Conceptual Art be beautiful? (And are there visually beautiful examples?)

Absolutely, but not always in the traditional sense of visual aesthetics. The beauty in Conceptual Art often lies in its intellectual elegance, its wit, its profundity, or its ability to spark a new way of seeing the world. A perfectly articulated idea, a deeply challenging question, or a poignant social commentary can be incredibly beautiful to the mind, even if the physical manifestation is stark or minimal. It's a beauty that resonates intellectually, rather than purely visually. For visually appealing examples that are also deeply conceptual, consider Felix Gonzalez-Torres's piles of individually wrapped candies (e.g., "Untitled" (Portrait of Ross in L.A.)), which, despite their minimal and consumable nature, create stunning, vibrant displays while addressing themes of love, loss, and impermanence. Or the meticulous, beautiful graphic layouts in some Art & Language text pieces, where the aesthetic of typography and composition contributes to the conceptual rigor. My own art, for instance, aims for both visual and conceptual beauty, hoping to engage both your eyes and your mind, proving that these aren't mutually exclusive.

Q6: What is Conceptual Photography?

Conceptual photography uses the medium not just to document reality, but to convey an idea or concept, often staging images or manipulating them to serve a specific intellectual proposition. The photograph becomes a vehicle for thought, much like text or performance in other conceptual practices. Think of John Baldessari's early works, which used appropriated photographs with text overlays to challenge narrative and meaning, or Cindy Sherman's Untitled Film Stills, where she photographs herself in various cinematic clichés, exploring themes of identity and representation. It’s photography with a purpose beyond mere capture.

Q7: What is Process Art, and how does it relate?

Process Art often emerged alongside Conceptual Art, sharing its rejection of the finished, static object. However, instead of prioritizing the idea above all else, Process Art emphasizes the actions and materials involved in the creation of the artwork. The process itself – the pouring, molding, stacking, or even the natural decay of materials – becomes the central focus of the work. While a conceptual artist might give instructions for an artwork to be executed (the idea is paramount), a process artist might focus on the act of pouring paint and letting it dry naturally (the process is paramount). There's often overlap, but the emphasis shifts subtly between the intellectual concept and the tangible act of making. You could say Process Art makes the how the art, while Conceptual Art makes the why the art.

Q8: What is the relationship between Conceptual Art and Minimalism?

This is a common point of confusion. Both Conceptual Art and Minimalism emerged around the same time and share an aesthetic of reduction, paring down to essential forms. Minimalists, like Donald Judd or Carl Andre, focused on industrial materials and geometric shapes, aiming for a direct, immediate, and often bodily experience of the object in space. The object itself and its physical presence were central. Conceptual Art, as we've discussed, shifts this focus from the physical object to the idea behind it. While artists like Sol LeWitt created minimalist forms (his grids, wall drawings), his work is fundamentally conceptual because the instructions – the idea – are the artwork, not the physical lines on the wall. So, while they share a reduced aesthetic, Minimalism is about the experience of the thing, and Conceptual Art is about the experience of the thought.

Q9: How has Conceptual Art influenced Digital Art and NFTs?

The rise of digital art and NFTs represents a fascinating evolution of Conceptual Art's core tenets. The dematerialization of the art object, a central tenet of conceptualism from the 1960s, finds its ultimate expression in purely digital forms that exist without a physical presence. The smart contract underlying an NFT, for instance, functions very much like a conceptual artist's instruction set or manifesto: it defines the artwork's existence, authenticity, ownership, and unique characteristics, making the underlying code and concept as, or more, important than the visual output. The ephemeral nature of some early conceptual works also resonates with the fluidity and potential for constant change or re-materialization in digital art. It's a direct lineage where the idea continues to reign supreme, albeit in a new, virtual realm.

Q10: Who are some other influential conceptual artists?

Beyond those already mentioned, figures like Jenny Holzer (known for her powerful LED text installations that challenge public spaces with provocative statements), Felix Gonzalez-Torres (whose piles of candy and stacks of paper invited viewer interaction and disappearance, embodying themes of loss and memory), and Ai Weiwei (who uses conceptual approaches to political and social commentary, often leveraging readymades and performance in his activism) continue to expand the legacy of Conceptual Art globally. Each of them demonstrates the incredible versatility and impact of idea-driven art, often using very different approaches to achieve their conceptual goals. There are so many more, but these names offer a great starting point for further exploration.

Q11: Is Conceptual Art always serious, or can it be humorous?

While much Conceptual Art tackles profound philosophical or social issues, it absolutely can be imbued with wit, irony, and even outright humor! Artists like John Baldessari often employed a wry, deadpan humor to question the conventions of art and language. The humor often arises from the absurdity of the proposition itself, the playful subversion of expectations, or the intellectual cleverness of the concept. It's a different kind of laughter – one that often comes with a sudden flash of understanding or a critical re-evaluation of something we take for granted. So yes, prepare to smirk and ponder simultaneously!

Q12: What role does the curator play in Conceptual Art?

In Conceptual Art, the curator's role often shifts from simply displaying objects to interpreting and facilitating the experience of an idea. For ephemeral works or instruction pieces, the curator might be responsible for executing the artwork (as in "Art by Telephone"), compiling documentation, or providing crucial contextual information that allows the audience to engage with the concept. Their role becomes one of intellectual gatekeeper and guide, ensuring the artist's original intent and conceptual framework are communicated effectively, making them almost a co-author of the experience. It's less about choosing pretty things and more about presenting compelling ideas.

Q13: What's the relationship between Conceptual Art and Performance Art?

This is a fantastic question, as they frequently overlap! Performance Art emphasizes the artist's body, actions, and presence as the primary medium, often unfolding in real-time before an audience. The experience and the event are central. Conceptual Art, however, prioritizes the idea or concept above all else. While many conceptual works employ performance (like Yoko Ono's Cut Piece or Adrian Piper's Catalysis), the performance itself serves as a vehicle for a broader intellectual proposition. In performance art, the action might be the art; in conceptual art using performance, the idea behind the action is the art. So, while they share a focus on non-traditional forms and audience engagement, performance art foregrounds the live event and the body, whereas conceptual art foregrounds the underlying thought that may or may not manifest as a performance.

Q14: How does Conceptual Art relate to Postmodernism?

Conceptual Art and Postmodernism are deeply intertwined, with the former often seen as a foundational element of the latter. Postmodernism, broadly, emerged as a reaction against the grand narratives and universal truths of modernism, embracing skepticism, irony, and a questioning of authority. Conceptual Art, by its very nature, fit perfectly into this framework. Its challenges to traditional notions of authorship, originality, aesthetic value, and institutional power directly aligned with postmodernist deconstruction. Both movements questioned the idea of a singular "masterpiece" or a definitive "meaning," instead emphasizing context, interpretation, and the fluidity of cultural production. So, you could say Conceptual Art provided many of the practical and theoretical tools for artists operating within a postmodern landscape, pushing art into a self-reflexive, critical mode.

Q15: What is the "commodity status" of art, and why did Conceptual Art challenge it?

The commodity status of art refers to the idea that artworks are primarily seen and valued as objects to be bought, sold, and collected, much like any other commercial good. This often places an emphasis on the physical artwork, its craftsmanship, and its potential for appreciation in monetary value. Conceptual Art explicitly challenged this by creating works that were ephemeral, intangible, or difficult to possess in a traditional sense – think of a performance, a set of instructions, or an idea itself. By stripping away the tangible object, conceptual artists sought to resist the art market's commercial pressures and to shift the focus back to the intrinsic artistic value of the idea, rather than its market price. It was a radical rejection of art as mere luxury goods.

Q16: What is the role of the viewer's interpretation in Conceptual Art?

In Conceptual Art, the viewer's interpretation is not just welcomed; it's often absolutely integral to the artwork's completion. Unlike traditional art where the viewer might passively admire a finished object, conceptual pieces frequently provide a framework – a question, a set of instructions, or a provocative statement – that requires the viewer to engage intellectually. Your thoughts, your reactions, your critical engagement, and even your actions become part of the art itself. The artist initiates a dialogue, but the meaning is often co-created in your mind, making you an active participant and co-creator of the artistic experience.

Q17: What are the economic implications of Conceptual Art?

The economic implications of Conceptual Art were profound and disruptive. By de-emphasizing the tangible art object, the movement directly challenged the traditional art market's valuation systems. How do you price an invisible gas release, a set of instructions, or a temporary performance? This forced galleries and collectors to redefine value, often leading to the sale of certificates of authenticity, documentation, or contracts rather than physical works. While initially controversial, this shift eventually expanded the market's understanding of what could be collected and valued, albeit in new forms. It also spurred the growth of alternative, artist-run spaces that operated outside the commercial gallery system, creating new economic models for artistic production and dissemination.

Conclusion: The Enduring Idea, The Liberating Thought

So, there you have it – my personal journey through the fascinating, sometimes frustrating, but always profoundly thought-provoking world of Conceptual Art. It's a movement that, for me, transformed art from something primarily to be seen into something primarily to be thought about. At its heart, Conceptual Art asserts that the idea or concept is the true artwork, with any physical manifestation serving merely as a vehicle for that thought.

It empowered artists with an unparalleled freedom of expression, allowing art to be a living, breathing question rather than just a static answer. And isn't that a beautiful, audacious thing? To distill meaning to its purest form, to challenge us to look beyond the surface, and to remind us that art can reside anywhere a compelling concept takes root. This liberation, for me as an artist, has been one of the most profound gifts Conceptual Art has given. It truly allows for limitless creative exploration, pushing me to consider the 'why' behind every brushstroke and the message embedded in every color. It’s an ongoing conversation, one that continually invites us to question, to ponder, and to grow.

I genuinely hope this guide serves as your ultimate resource, helping you feel a little less lost, and a lot more intrigued. Perhaps it even inspires you to seek out and engage with some conceptual pieces yourself, either in a gallery, right here in my collection at /buy, or by delving deeper into the questions raised in our FAQ! You can also follow my artistic process and inspiration on my /timeline, where you'll see how concept and color intertwine in my own work. So, the next time you encounter something that makes you scratch your head in a gallery, remember: it might just be the most profound artwork you'll encounter all day – if you let your mind do the looking.