The Enduring Legacy of Keith Haring: Art for All

Explore Keith Haring's vibrant journey from subway artist to global icon. Discover his philosophy of art for all, his iconic symbols, and his powerful activism against AIDS and social injustice. Learn about his enduring impact on contemporary art and LGBTQ+ history.

The Enduring Legacy of Keith Haring: Art for All

Imagine art so alive, so utterly ubiquitous, that it feels less like a creation and more like a force of nature. That's Keith Haring for me. I can't pinpoint the first time I saw a Haring – it was probably on a t-shirt, a poster, or even a pencil case. Those bold, dancing lines, the radiant baby, the barking dog – they just were. They were everywhere, a visual language I instinctively understood, long before I grasped the profound message of art for all that pulsed beneath their playful, joyful surface, addressing everything from social justice to the AIDS crisis. It's funny how some art seeps into the cultural consciousness, becoming so pervasive that the artist almost disappears behind their own creations. As an artist myself, I often grapple with this very challenge: how to create work that is both deeply personal and universally understood, art that lives beyond the canvas and truly belongs to everyone. I've spent countless hours in my studio, wrestling with a single brushstroke, wondering if it would ever truly 'speak' beyond my own four walls. Keith Haring was no disappearing act; he was a vibrant, unapologetic explosion of creativity and purpose, and his art spoke volumes to millions. His story, his philosophy, and his sheer audacity continue to resonate deeply with me. Join me as we dive into the world of this extraordinary artist, exploring his journey from humble beginnings to global icon, and uncovering the enduring power of his art and activism.

From Pennsylvania to Pop: Haring's Early Journey

Before he became the undisputed king of the New York City subway, Keith Haring's artistic journey began in a small town in Pennsylvania. Born in Reading in 1958, he grew up in Kutztown, a place far removed from the bustling art scene he would later conquer. His early influences were a fascinating mix: his father, an amateur cartoonist, instilled in him a love for drawing and popular imagery. He was also deeply fascinated by Dr. Seuss, Walt Disney, and the vibrant world of comic books. You can see echoes of this in his later work – the bold, continuous lines reminiscent of cartooning, the simplified, almost childlike figures that evoke storybook characters, and the dynamic movement that feels straight out of an animated short. This early exposure to accessible, narrative-driven visuals would profoundly shape his later work.

After a brief stint at the Ivy School of Professional Art in Pittsburgh, Haring quickly realized that traditional art education wasn't quite his path. He found the structured, often elitist environment of formal art schools stifling, a stark contrast to the raw, democratic energy he craved. He wasn't interested in mastering classical techniques for the sake of gallery walls; he wanted to communicate, to connect, to make art that lived and breathed with the city. It's a feeling I know well – that moment when the prescribed path feels like a straitjacket, and the true calling whispers from an unexpected corner. For me, it was less about subway walls and more about the quiet rebellion of abstract expression, but the underlying urge to break free and find an authentic voice resonates deeply.

In 1978, he made the pivotal move to New York City to attend the School of Visual Arts. It was here that he truly found his voice, shedding academic constraints and embracing the city itself as his ultimate canvas and inspiration. This period was a whirlwind of experimentation; before his iconic subway drawings, Haring was deeply involved in performance art and video work, often creating spontaneous pieces in public spaces or documenting his artistic interventions. This early exploration of ephemeral, public-facing art laid crucial groundwork for his later, more recognized street art. He immersed himself in the downtown art scene, a melting pot of graffiti artists, musicians, and performers, where he connected with kindred spirits like Jean-Michel Basquiat and Kenny Scharf. This downtown scene was a vibrant, often chaotic crucible of creativity, where boundaries between disciplines blurred. It was a place where hip-hop was exploding, where disco reigned in underground clubs, and where artists like Basquiat and Scharf were already pushing the boundaries of what art could be. Haring didn't just observe; he absorbed the pulsating rhythm of the city, the urgent social dialogues, and the burgeoning hip-hop and club culture, all of which would infuse his art with an undeniable, infectious energy. This period was crucial; it was where his philosophy of art as a public, democratic act truly began to solidify.

Subway Canvas, Street Soul: Haring's Radical Act of Art for All

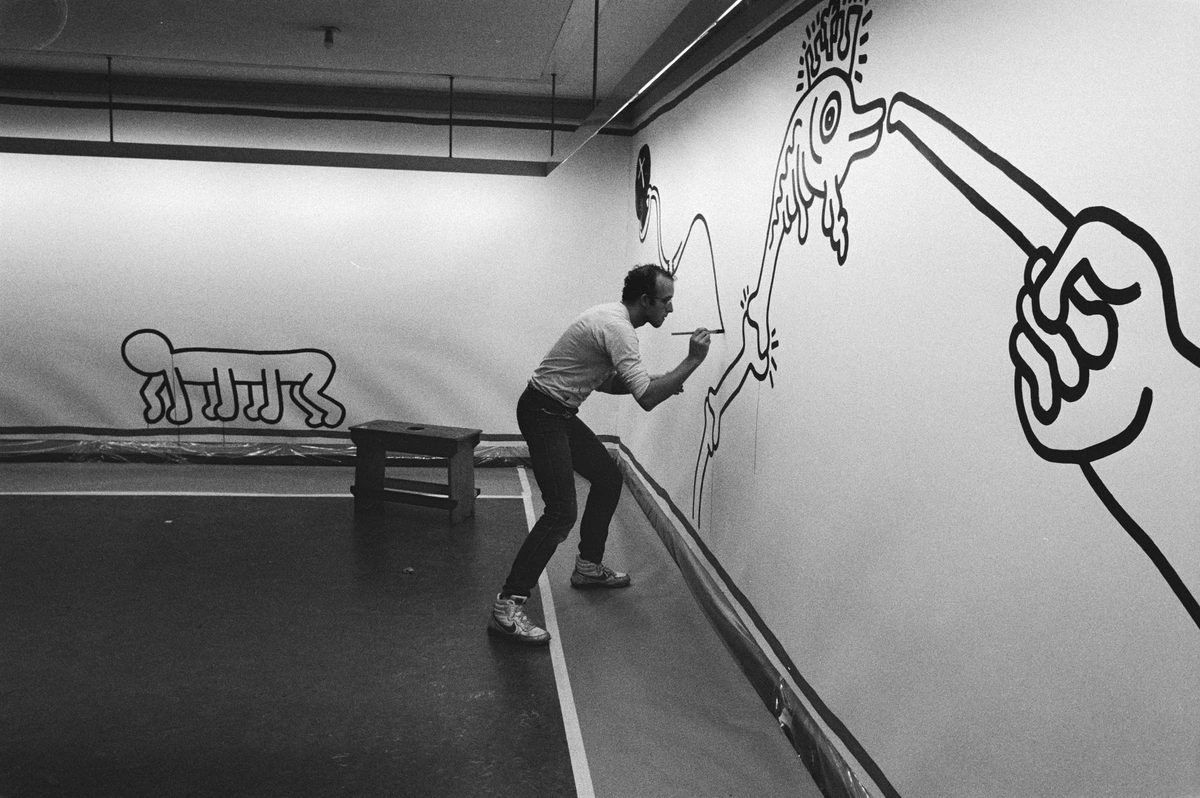

Haring's journey began not in a pristine studio, but in the gritty, pulsating heart of 1980s New York City. He wasn't interested in art that was locked away in elite institutions, only accessible to a select few. No, Haring wanted his art to breathe, to live, to interact with the very people who inspired it. This is where his iconic "subway drawings" come in.

Imagine, if you will, the sheer brilliance – and audacity – of seeing an empty black advertising panel in a subway station and thinking, "That's my canvas." These weren't just blank spaces; they were often empty black advertising panels, temporary covers for old ads, making his chalk drawings a direct, fleeting intervention into the commercial landscape. He didn't just think it; he acted on it, creating literally thousands of these spontaneous works with white chalk, often quickly, with the constant risk of arrest. The sheer scale of his output in these public spaces is astounding; he was a prolific machine, churning out pieces with an almost performative intensity. The air thick with the rumble of trains and the murmur of commuters, he'd work with a focused intensity, his bold lines emerging with astonishing speed. Commuters would often stop, captivated, sometimes even forming a protective circle around him as he worked, occasionally even distracting a passing police officer just long enough for him to finish a piece. The art was ephemeral, existing only until the next advertisement covered it or the police intervened. Yet, this fleeting nature was part of its power, forcing immediate engagement and making art truly accessible to daily commuters.

It's a concept that still makes my artist's heart sing. The idea of art as a public conversation, a democratic act. It reminds me of the raw, unfiltered energy of street art and how it challenges our notions of what art is and who it's for. Haring wasn't just drawing; he was reclaiming public space, making art for everyone. As an artist, I often find myself drawn to the idea of creating work that exists outside the traditional gallery space, perhaps a mural that brightens a forgotten corner, or a piece that sparks a moment of unexpected joy in a mundane setting. Though, I must admit, my own attempts at public art usually involve leaving a small, anonymous sketch on a coffee shop napkin, far from the risk of arrest. The thought of chalking up a subway wall? My palms are sweating just thinking about it! I mean, the sheer guts of it! My internal monologue would be screaming, "Run! They're coming for you!" And probably, "Also, is this chalk archival? Will it smudge? Oh god, the pressure!" Haring, on the other hand, was pure, unadulterated artistic courage.

Decoding the Doodles: Haring's Universal Language of Lines

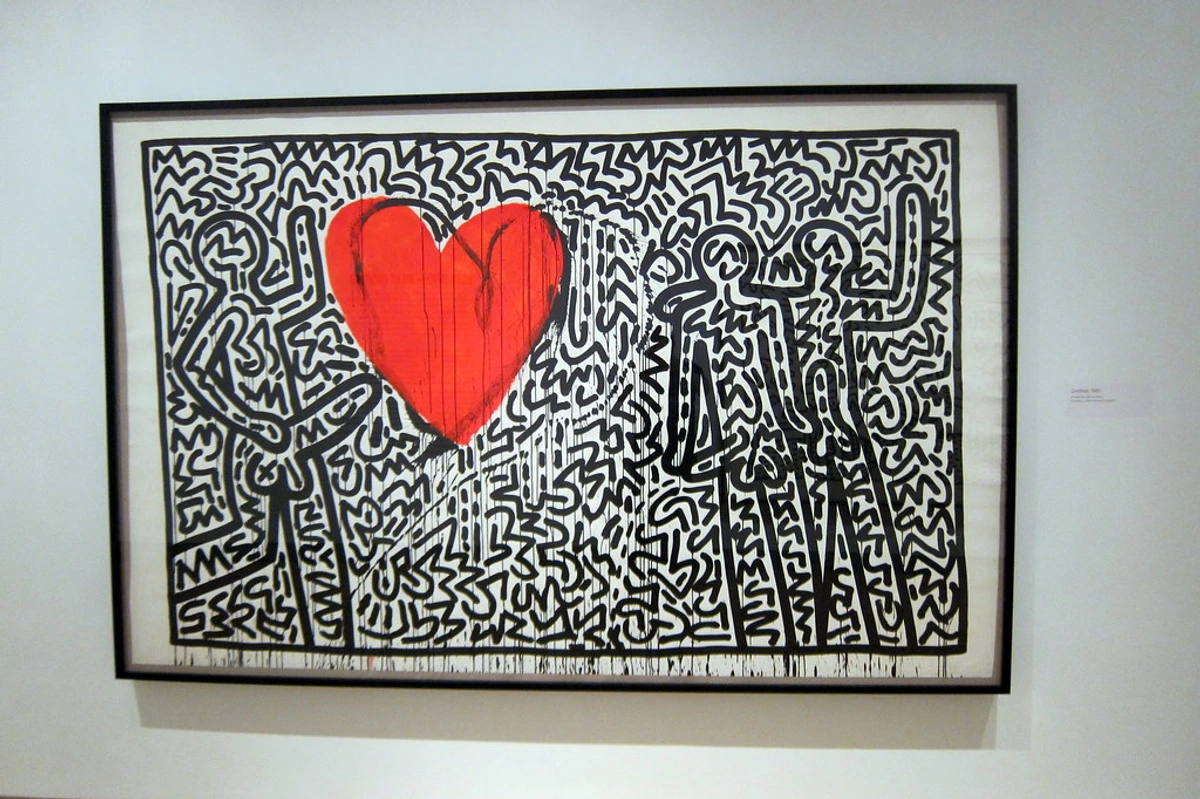

Haring's visual vocabulary is deceptively simple. Just a few lines, a few figures, and yet, they convey so much. It's a masterclass in semiotics – the study of signs and symbols and how they convey meaning. Haring understood that by stripping away unnecessary detail, he could create universal 'signs' (like the radiant baby or barking dog) that instantly communicated complex 'meanings' across diverse audiences, without needing words. He tapped into primal forms, archetypes that resonate across cultures, stripping away the unnecessary to leave only the essence of a message. He created a visual shorthand that spoke volumes.

Crucially, Haring often combined and layered these symbols, creating complex narratives and evolving meanings within a single work. A radiant baby might be seen alongside a barking dog, suggesting innocence threatened by authority, or figures with holes in their stomachs might dance with joy, highlighting resilience amidst suffering. This interplay of symbols allowed his art to be both immediately accessible and profoundly nuanced, reflecting the multifaceted realities of the issues he addressed.

The "radiant baby" – a crawling infant with lines emanating from it – is perhaps his most iconic symbol, representing innocence, purity, and new beginnings. It's a beacon of hope in a world often fraught with darkness, famously appearing in works like his "Radiant Baby" series and often integrated into larger murals. Then there's the "barking dog," often seen as a symbol of authority, aggression, or even a warning against societal ills, prominently featured in his "Dogs" series and numerous public pieces. But Haring's lexicon extended further, each figure a potent shorthand for complex ideas:

- The Radiant Baby: Symbol of innocence, purity, and new beginnings. (e.g., "Radiant Baby" series, various murals)

- The Barking Dog: Often represents authority, aggression, or a warning against societal ills. (e.g., "Dogs" series, "Crack is Wack" mural)

- The Three-Eyed Monster: Often interpreted as a symbol of greed, corruption, or surveillance, a watchful, malevolent force. (e.g., "Three-Eyed Monster" series, "Reagan" works)

- Flying Saucers/UFOs: Representing external forces, often oppressive or alienating, descending upon humanity. (e.g., "UFO" series, "Apocalypse" series)

- Figures with Holes in their Stomachs: A stark visual representation of the emptiness or vulnerability caused by societal issues like drug abuse or AIDS. (e.g., "Ignorance = Fear, Silence = Death" poster, "AIDS" series)

- The Pyramid/Triangle: Often used to represent stability, hierarchy, or even spiritual enlightenment, but in Haring's context, sometimes inverted or combined with other symbols to critique power structures. (e.g., "Pyramid" series, "USA" works)

- The X Mark: Often used to signify censorship, prohibition, or a target, highlighting societal restrictions or dangers. (e.g., "Free South Africa" poster, various anti-drug works)

These weren't just cute doodles; they were potent symbols, understood across cultures and languages. As an artist, I often grapple with how to communicate complex ideas with clarity. I once tried to convey the feeling of existential dread using only abstract shapes, and someone asked if it was a map of the local bus routes. My inner critic immediately chimed in, "Well, that's a fail, isn't it?" It's a constant battle, this quest for clarity and universality in my own abstract work. Haring mastered this. He stripped away the unnecessary, leaving only the essence, tapping into something primal and universally understood. It's a profound lesson in design in art and the power of visual storytelling. His work is a testament to the idea that profound messages don't need elaborate forms; sometimes, the simplest lines speak the loudest.

Collaborations & Community: Art as Connection

Haring was a master collaborator, understanding that art could be a powerful force for connection and community building. His immersion in the vibrant downtown New York scene meant his art was deeply intertwined with the music, fashion, and performance art of the era. He wasn't just an artist; he was a fixture in the legendary clubs like the Mudd Club and Paradise Garage, where he found inspiration in the raw energy of the dance floor and the diverse crowds. This environment fueled his belief in art as a communal, accessible experience.

He worked with an astonishing array of individuals and groups, blurring the lines between art, music, fashion, and social activism. His friendships and collaborations with fellow artists like Jean-Michel Basquiat and Andy Warhol were well-known, but his reach extended far beyond the art world elite. He designed album covers for artists like Run-DMC, created sets for choreographers, and even collaborated with pop icon Madonna, using her platform to further disseminate his messages. These weren't just one-off projects; they were strategic alliances that amplified his voice, pushing his art and its urgent social messages into mainstream consciousness. For instance, his work with Madonna, famously painting her body for a performance at the Paradise Garage, transformed her into a living, moving canvas, bringing his democratic art philosophy to a massive, diverse audience who might never visit a gallery. Similarly, his album cover for Run-DMC's 'King of Rock' introduced his art to millions of hip-hop fans, proving his art truly was for everybody and demonstrating how art could seamlessly integrate with popular culture to spread powerful ideas. His workshops with children were legendary, actively engaging them in creating spontaneous, joyful murals that celebrated their uninhibited creativity. I can only imagine the pure, unadulterated joy of those kids, drawing alongside a master who truly saw their innate artistic spirit. These collaborations weren't just about creating art; they were about fostering dialogue, building bridges, and empowering marginalized voices. It was a truly inclusive approach to art-making, demonstrating his belief that art should be a shared experience, a collective endeavor that brings people together. This collaborative spirit and desire for universal connection naturally propelled his art beyond the confines of New York, onto a global stage.

Art as Activism: A Megaphone for the Marginalized

But what happens when playful lines meet profound purpose? For Haring, art was never just about aesthetics; it was a megaphone for change. Beyond the playful aesthetic, his art carried a powerful social and political punch. He lived through the AIDS epidemic, a time of immense fear, prejudice, and loss. Crucially, Haring himself was diagnosed with AIDS in 1988, which added an incredibly poignant and urgent layer to his already prolific output. It was a race against time, a desperate need to communicate his message before his own light faded. This personal battle infused his later works with an even more profound sense of urgency and raw emotion.

His work became a direct, visceral response, raising awareness, advocating for safe sex, and challenging the stigma surrounding the disease. Pieces like "Ignorance = Fear, Silence = Death" are not just art; with their stark, almost skeletal figures, often with an 'X' over their mouths, and urgent, bold text, they are cries for justice, calls to action that undoubtedly saved lives by promoting education and empathy. The three figures in this iconic poster, often depicted in a dance of fear and silence, powerfully convey the devastating impact of inaction. This powerful slogan, often seen on posters and buttons, became a rallying cry for activists and a stark reminder to the public. Haring famously stated, "Art is for everybody," and he truly lived that, especially when it came to life-saving information.

Haring's commitment extended beyond the AIDS crisis. He famously created the "Crack is Wack" mural in Harlem in 1986, a powerful, unauthorized public artwork that, with its frantic, chaotic energy and bold, direct message, served as a stark warning against the crack cocaine epidemic ravaging communities. The mural, created on a handball court wall, was initially unauthorized, leading to his arrest. But the public outcry and support were so immense that the charges were dropped, and the mural was eventually preserved, becoming a powerful, permanent landmark against the drug epidemic. This piece, like his subway drawings, was a direct intervention in public space, using art to address urgent social issues head-on. He collaborated extensively with organizations like ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) and created numerous public service announcements and murals for causes ranging from literacy to children's welfare. He tackled other pressing issues too: apartheid, drug abuse, and the crack epidemic. He understood that art could be a potent tool for change, a megaphone for the marginalized. This commitment to using his platform for good is something I deeply admire and constantly reflect on in my own practice. There was a time, early in my career, when I felt a strong urge to create a series of pieces addressing local environmental concerns. The struggle wasn't just the aesthetic, but how to make complex scientific data visually compelling without being preachy. Haring's work always reminds me that the most impactful art often dares to speak truth to power. It's a powerful reminder of the history of protest art and its enduring relevance.

Pop Art's Maverick: Commercialism as Accessibility

Haring is often categorized under Pop Art, and rightly so. Pop Art, emerging in the 1950s and 60s, challenged traditional fine art by embracing popular culture, consumerism, and mass media imagery. It blurred the lines between "high" and "low" art, often using commercial techniques like screenprinting. Like Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein, he embraced commercial imagery and mass production. He was part of a vibrant downtown New York art scene, often interacting with figures like Warhol and Jean-Michel Basquiat. While Warhol explored celebrity and consumerism with a detached, almost clinical eye, and Basquiat brought raw, neo-expressionist energy, Haring's approach to commercialism was distinct.

Artist | Primary Focus of Commercialism | Approach to Mass Production | Distinctive Philosophy (re: commercialism) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Andy Warhol | Celebrity, consumer products | Detached, ironic | Art as product, blurring high/low art |

| Roy Lichtenstein | Comic strips, advertising | Mechanical reproduction | Elevating commercial art to fine art |

| Keith Haring | Accessibility, social message | Democratic, inclusive | Art for everyone, breaking gallery barriers |

His famous Pop Shop, opened in 1986, was met with criticism from some in the art establishment who accused him of "selling out." But Haring vehemently defended it as an extension of his democratic art philosophy. He wanted everyone, regardless of their income, to own a piece of his work – a t-shirt, a poster, a button. Stepping into the Pop Shop was an experience in itself – a vibrant, playful space filled with his iconic imagery on everything from buttons and t-shirts to posters and small sculptures. It was less a sterile gallery and more a bustling, democratic marketplace of ideas, a direct challenge to the exclusivity of the traditional art world. Crucially, the Pop Shop was also a significant financial success, proving that art could be both accessible and commercially viable, directly challenging the elitist art market. You could walk out with a piece of Haring for a few dollars, a radical notion at the time, making art collecting accessible to everyone, not just the elite. It even served as an educational space, introducing his powerful messages to a wider audience. He believed that art should not be exclusive, but rather a part of everyday life, a sentiment that deeply resonates with my own desire to make art accessible through prints and other mediums.

I can relate to the tension between artistic integrity and commercial viability. It's a tightrope walk for any artist, and frankly, one I'm still navigating myself. Just last week, I had a moment of existential dread wondering if selling a particularly popular print was "diluting" the original painting's message. I mean, is it still "art" if it's on a coffee mug? It's a fascinating irony, isn't it? What was once criticized as 'selling out' is now celebrated as a pioneering act of accessibility, a testament to his unwavering belief that art should permeate every aspect of life. I often wonder if my own small prints, sold online, carry a similar, albeit quieter, echo of that democratic spirit. Haring walked it with conviction, believing that selling t-shirts and posters wasn't "selling out" but rather "buying in" to his vision of art for the masses. His courage in the face of criticism gives me perspective. It's a fascinating aspect of his timeline and how he navigated the art market. This commitment to widespread accessibility, whether through subway chalk drawings or Pop Shops, naturally led him to expand his reach even further, taking his message to a global stage.

Global Murals & Public Art: Spreading the Message Worldwide

Haring's commitment to public art wasn't confined to the New York subway. He was a true global artist, traveling extensively to create large-scale murals and public installations that brought his distinctive style and powerful messages to communities around the world. From Paris to Berlin, Pisa to Melbourne, his vibrant figures popped up on walls, buildings, and even the Berlin Wall itself.

These international projects were often commissioned for specific social or political causes, reinforcing his belief that art could be a universal language for change. He worked with astonishing speed and precision, often scaling his smaller designs onto massive walls with a fluidity that belied the scale, sometimes using a projector for initial outlines but mostly relying on his incredible freehand ability and innate sense of proportion. These projects were rarely solitary; he frequently involved local communities, especially children, in the painting process, transforming the act of creation into a shared, empowering experience. Imagine the sheer energy of a community coming together, brushstrokes by brushstrokes, to bring a Haring mural to life! For instance, his 1986 mural on a section of the Berlin Wall, depicting a chain of dancing figures, symbolized hope and unity in a divided city. The mural was created just three years before the wall fell, and its vibrant message of connection resonated deeply with Berliners on both sides, becoming a powerful, visible symbol of the desire for freedom and togetherness. In Pisa, Italy, his monumental mural "Tuttomondo" (All World) covers an entire side of a church, a vibrant celebration of peace and harmony. He worked quickly, often involving local communities and children in the creation process, further embedding his art within the fabric of everyday life and making it truly theirs. This global reach amplified his voice, ensuring his messages about AIDS awareness, anti-apartheid, and children's welfare resonated far beyond the streets of New York. It's a powerful reminder that art can truly transcend borders and languages, speaking directly to the human spirit. As an artist, I often dream of creating work that has such an immediate, universal impact, a piece that resonates with someone halfway across the world, even if they don't speak my language. The thought of tackling a wall the size of the Berlin Wall, though? My arm aches just contemplating the sheer physical endurance required! It's a testament to his tireless work ethic and his unwavering dedication to his mission.

Collecting Keith Haring: A Piece of History for Your Home

Given his philosophy, it's no surprise that collecting Keith Haring's work can be more accessible than you might imagine. He intended for his art to be widely available, a direct extension of his "art for all" ethos. While original canvases command high prices, his prints, posters, and even merchandise offer a way to own a piece of this iconic artist's legacy, ranging from a few dollars for buttons and t-shirts to hundreds or even thousands for limited edition lithographs and screenprints. When considering prints, you'll often encounter different types, such as lithographs (created from a drawing on a stone or metal plate) or screenprints (like the ones Warhol famously used, where ink is pushed through a mesh screen). Many of these are part of limited editions, meaning only a specific number were produced, which can influence their value.

However, a word to the wise: given his popularity, always ensure authenticity when purchasing prints or merchandise, especially if a deal seems too good to be true. Common red flags for fakes include blurry lines, incorrect paper quality, a lack of expected edition numbers or signatures, or suspiciously low pricing. Researching the provenance and reputable dealers is key. For those looking to acquire authentic pieces, established galleries specializing in Pop Art or contemporary art, and reputable auction houses (especially those with dedicated print departments) are the best places to start. They can provide provenance and ensure authenticity, which is crucial in a market with many fakes. I once almost bought a "signed" print online that turned out to be a very convincing fake – a harsh lesson in due diligence! My heart sank faster than a lead balloon when I realized. There's a unique joy in owning a piece of Haring's work, even a print. It's not just a beautiful image; it's a tangible connection to a powerful message, a piece of history that continues to radiate hope and activism. It's like having a tiny, vibrant megaphone on your wall, reminding you that art can, and should, change the world.

If you're looking to buy art or specifically buy art prints, Haring's work is a fantastic entry point. It's a vibrant, conversation-starting addition to any space, and yes, art prints can be a good investment if chosen wisely. Understanding art editions can also help you make informed decisions. His work looks fantastic in a modern living room or even a minimalist interior, adding a playful yet profound touch.

The Enduring Echo of His Lines

Keith Haring's life was tragically cut short due to complications from AIDS in 1990, at the age of 31. His decline was rapid, a stark and painful reminder of the epidemic's devastating toll, but it only fueled his incredible prolificacy in his final years. He worked with a fierce urgency, knowing his time was limited, pouring his remaining energy into creating as much art as possible to spread his vital messages.

But his impact continues to reverberate. He showed us that art doesn't need to be confined to galleries or understood only by critics. It can be a tool for social change, a source of joy, and a universal language. His legacy is a testament to the power of authenticity, passion, and the belief that art truly belongs to everyone.

Haring's profound influence extends into LGBTQ+ art history, where he stands as a pivotal figure. His open identity and direct engagement with the AIDS crisis through his art provided a powerful voice and visibility for a community often marginalized and silenced. His art became a visual language for the queer community, offering symbols of solidarity, defiance, and resilience during a period of immense fear and loss. He didn't just depict the crisis; he actively fostered a sense of community and empowered individuals to speak out, transforming silence into a powerful visual and social movement. His work paved the way for future generations of LGBTQ+ artists to express their experiences and advocate for change.

His influence on contemporary art is undeniable. Artists today, particularly those engaged in street art, public art, or social activism, often cite Haring as an inspiration. You can see echoes of his bold lines and accessible messaging in the work of artists like KAWS, with his playful yet poignant character designs, and Shepard Fairey, known for his iconic street art and politically charged posters – both carrying forward Haring's spirit of public engagement and universal visual language. He remains one of the most important artists of his time.

The Keith Haring Foundation continues his work today, not just preserving his artistic and philanthropic legacy, but actively supporting art education programs for children, funding AIDS research and care initiatives, and advocating for LGBTQ+ rights and social justice worldwide. It's inspiring to see his vision live on through such tangible efforts.

When I visit a museum, like the Den Bosch museum or any other institution showcasing modern art, I often think of Haring. What comes to mind is the sheer joy and unbridled energy of his lines, the way he could convey so much with such apparent simplicity. He reminds me that while technique and concept are vital, the heart of art lies in its ability to connect, to provoke, and to simply be seen. For me, his legacy is a constant whisper: 'Don't just make art; make it matter. Make it for everyone.' How many artists can truly say their work became a part of the everyday fabric of life for millions, transcending the art world to become a symbol of hope and activism? Not many, I tell you. Not many. And through it all, his art continues to radiate an undeniable sense of hope and vibrant optimism, a powerful counterpoint to the darkness it often confronted.

Frequently Asked Questions About Keith Haring

Still curious? Here are some common questions I often hear about Haring's incredible journey and enduring impact:

What is Keith Haring famous for? Keith Haring is famous for his distinctive, bold line drawings and iconic figures like the "radiant baby" and "barking dog." He gained prominence for his public art, particularly his chalk drawings in New York City subway stations, and for using his art to advocate for social and political causes, including AIDS awareness, anti-apartheid, and anti-drug messages.

What art movement is Keith Haring associated with? Keith Haring is primarily associated with the Pop Art movement, though his work also incorporates elements of street art and graffiti. He emerged alongside artists like Andy Warhol and Jean-Michel Basquiat, sharing their interest in popular culture and mass media.

What was Keith Haring's artistic process like? Haring's artistic process was characterized by its spontaneity, speed, and public nature. He often worked quickly, especially on his illegal subway drawings, using bold, continuous lines. He was incredibly prolific, often working on multiple pieces simultaneously, driven by a tireless work ethic and a sense of urgency. He often worked to the pulsating rhythms of hip-hop and disco, which fueled the dynamic, almost dance-like energy of his lines, making his art feel alive and in motion. His studio practice involved painting on canvas, tarpaulins, and objects. He embraced various mediums, from spray paint to markers, and frequently collaborated with other artists and musicians. His process was less about meticulous planning and more about immediate expression and direct engagement with his environment.

Who influenced Keith Haring's style? Keith Haring's style was influenced by a diverse range of sources. He drew inspiration from graffiti art, comic books, Egyptian hieroglyphics, and tribal art – particularly their emphasis on simplified forms, bold outlines, and narrative storytelling that could convey complex ideas universally. His early studies in semiotics also played a crucial role in developing his universal visual language. While he attended the School of Visual Arts, he consciously broke from traditional academic approaches, preferring the raw energy of the street. Artists like Pierre Alechinsky and Jean Dubuffet, with their focus on spontaneous drawing and raw art, also had an impact. He synthesized these influences into his unique, instantly recognizable style.

Where can I see Keith Haring's art today? Keith Haring's work is exhibited in major museums worldwide, including the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, the Centre Pompidou in Paris, and the Tate Modern in London. You can also find his public murals and installations in various cities globally, and his designs are still widely reproduced on merchandise.

Is Keith Haring's art still relevant? Absolutely. Keith Haring's art remains incredibly relevant today. His themes of social justice, equality, and the fight against disease are timeless. His accessible style continues to inspire new generations of artists and activists, proving that art can be both profound and universally understood.

What is the Keith Haring Foundation and what does it do? The Keith Haring Foundation was established by the artist himself in 1989, a year before his death. Its primary mission is to preserve and protect his artistic and philanthropic legacy. This includes maintaining his archive, overseeing the licensing of his imagery, and supporting organizations that provide educational opportunities for underprivileged children, fund AIDS research and care, and advocate for LGBTQ+ rights and social justice worldwide. Beyond its mission, the Foundation has achieved significant milestones, including establishing major endowments for art education, funding groundbreaking AIDS research, and ensuring Haring's public art remains accessible and preserved for future generations. It ensures his vision of art as a tool for positive change continues to impact the world.

How did Keith Haring's personal experiences influence his art style? Haring's personal experiences profoundly shaped his artistic style and thematic focus. His upbringing in a conservative Pennsylvania town fueled his desire for accessible, democratic art. His immersion in the vibrant, diverse New York City downtown scene, with its burgeoning hip-hop and club culture, infused his lines with dynamic energy and a sense of communal celebration. Most significantly, his AIDS diagnosis in 1988 brought a fierce urgency and a darker, more direct tone to his work. Figures became more skeletal, themes of death and struggle became more explicit, and his prolificacy intensified as he raced against time to spread his messages of awareness and compassion. His art evolved from playful exuberance to a powerful, poignant call to action, directly reflecting his lived reality.

What was Keith Haring like as a person? By all accounts, Keith Haring was known for his boundless energy, generosity, and unwavering optimism, even in the face of his AIDS diagnosis. He was deeply committed to his ideals, approachable, and genuinely loved interacting with people, especially children. Friends and collaborators often described him as charismatic, driven, and incredibly kind, always eager to share his art and its message with the world. He lived with a fierce urgency, driven by his belief in art's power to communicate and heal.

What was Keith Haring's relationship with other artists of his time? Keith Haring was deeply embedded in the vibrant New York art scene of the 1980s, fostering significant relationships with many contemporaries. He was particularly close with Jean-Michel Basquiat, sharing a similar drive for public art and social commentary, and they often influenced each other's work. He also famously collaborated with Andy Warhol, who became a mentor figure, and worked alongside artists like Kenny Scharf. These relationships were not just professional; they were part of a tight-knit community that defined the era's artistic landscape, pushing boundaries and challenging the art establishment together.

Have there been major Keith Haring exhibitions since his death? Absolutely. Keith Haring's work continues to be celebrated globally with numerous major exhibitions. Notable retrospectives include 'Keith Haring: The Political Line' (2014-2015) at the de Young Museum in San Francisco and the Brooklyn Museum, and 'Keith Haring' (2019) at Tate Liverpool and Centre Pompidou. His art is a staple in permanent collections of major institutions worldwide, ensuring his messages remain visible and relevant to new generations.