90s Art Scene: Quiet Revolutions, Provocateurs, & Lasting Legacy

Explore the 90s art scene's 'quiet revolutions' through my personal journey. Discover its profound impact, from postmodernism, digital art, and activism to globalization, shaping contemporary art and my abstract practice.

The 90s Art Scene: A Personal Journey Through Quiet Revolutions and Lasting Legacy

The 90s, huh? For me, it always feels like this fuzzy bridge between the neon-soaked excess of the 80s, which often screamed for attention with its bombastic statements, and the digital explosion of the 2000s. It was a decade where things felt... quieter, perhaps? More introspective, even as they quietly redefined their own essence.

And art? Oh, art was having a moment. A big, messy, beautiful moment – a time of 'quiet revolutions' that gently redefined the very essence of artistic expression. Think of it less as a single, roaring wave and more as countless ripples spreading outwards, transforming the landscape beneath the surface. Beyond the iconic flannel shirts and the lingering hum of dial-up internet, the decade also saw the rise of indie film, alternative fashion trends, and a flourishing zine culture, all echoing a pervasive sense of introspection and a DIY spirit that quietly permeated the art world. Even the music scene, with its raw grunge aesthetics and the vibrant visual language of hip-hop and electronic music videos, mirrored this artistic re-evaluation, pushing against polished norms and embracing a deliberate 'anti-fashion' that echoed the art world's rejection of slickness, hinting at a deeper, more authentic search for meaning.

This era, with its delightful quirks and profound shifts, truly laid the groundwork for my own pursuit of beauty in the abstract and unexpected – shaping how I now play with layered forms and unexpected color shifts to evoke that same sense of quiet transformation – a subtle rebellion against the obvious that seeks to unveil hidden narratives within each brushstroke and shadow. Indeed, the 90s stand as a unique transitional decade in art history, gently but powerfully shifting paradigms, offering a blueprint for the art world we inhabit today.

I remember vividly encountering Damien Hirst's – that shark in formaldehyde. My first thought was, "Is this really art? Or just a very expensive piece of taxidermy that someone accidentally left in a gallery?" Then came the flood of fascination, the questions it provoked, the sheer audacity. That moment, a blend of initial confusion and exhilarating intellectual wrestling, perfectly encapsulates the 90s art scene for me. Later, the decade felt like the kind of time you'd find yourself staring intently at a seemingly mundane object – perhaps a forgotten turnip in a minimalist performance piece – for ten minutes, earnestly asking, 'Is this a commentary on consumerism, a meditation on permanence, or just an existential crisis with a side of starch on a pedestal?' Yet, that audacity of simplicity, that quiet provocation, slowly grew on me. It taught me to appreciate the beauty in the delightfully odd, a perspective I still chase in my own abstract works. This era, in all its perplexing diversity, truly cemented art's boundless capacity for reinvention. I distinctly recall a quiet revolution unfolding within my own studio, too: a sudden realization that a seemingly 'wrong' color combination could unlock a deeper emotion, much like the unexpected juxtapositions in 90s art.

These personal encounters mirrored broader shifts. If the 60s roared with the defiant splashes of Abstract Expressionism or the vibrant, commercial embrace of Pop Art, the 90s hummed with a different kind of energy. It wasn't about grand, sweeping declarations or overt manifestos; instead, it was a decade of gentle yet profound shifts – what I like to call 'quiet revolutions.' These weren't always loud or confrontational, but rather a slow, internal reordering of artistic thought and perception, inviting us to look deeper into the seemingly mundane or shocking, often as a direct counterpoint to the more bombastic statements of the previous decade.

So, what exactly was brewing beneath the surface of the 90s, beyond the grunge and dial-up? Let's unravel the threads of a decade that redefined art from the inside out.

The Shifting Landscape: A Decade of Unraveling and Reweaving

The 90s presented a complex tapestry of transformations, driven not just by internal artistic impulses but by monumental societal changes and rapid technological advancements. The fall of the Berlin Wall, the end of the Cold War, and the nascent forces of globalization were dramatically reshaping political and economic landscapes. These profound shifts created the fertile ground for the 'quiet revolutions' that redefined the very parameters of artistic expression. And for me, within this dynamic backdrop, I started to notice art speaking a new language, one of deconstruction, skepticism, and unprecedented interconnectedness.

The Postmodern Turn: Shifting Realities

At its core, Postmodernism was a rejection of grand narratives and universal truths – those overarching stories or beliefs that society once held as absolute. Remember when everyone started saying 'post-modern' all the time? Or was that just me, trying to sound smart at art school, awkwardly trying to explain Foucault over Thanksgiving dinner? It felt like we were all collectively shrugging, acknowledging that the grand narratives had crumbled, and now what? This intellectual current embraced instead a playful, often ironic, skepticism towards objective reality, inviting endless questioning and reinterpretation. This exhilarating freedom, however, also drew criticism for perceived cynicism, intellectual elitism, or a lack of originality.

This era also saw the increasing influence of art schools and MFA programs in shaping intellectual discourse, providing a rigorous, often theoretical, framework that sometimes felt miles away from the raw creativity of the studio. For me, navigating these theoretical discussions was often like trying to untangle a particularly stubborn knot while simultaneously attempting to paint a masterpiece – a challenge that ultimately taught me to appreciate intellectual rigor alongside the messy process of making. The burgeoning field of critical theory, influenced by thinkers like Jacques Derrida and Michel Foucault, provided crucial frameworks for analyzing power structures, language, and culture, empowering artists to deconstruct and question established norms.

In art, this meant embracing pastiche, irony, and deconstruction, often recontextualizing historical styles or commercial imagery. Artists like Sherrie Levine, who rephotographed iconic works by male artists like Walker Evans, and Richard Prince, known for his 'rephotography' of Marlboro Man advertisements, perfectly encapsulated this spirit of appropriation, challenging notions of authorship and originality. My own professors wrestled with it, and I recall a moment of profound confusion – and then exhilarating clarity – realizing that art didn't have to provide the answer, but rather explore all the questions. This freedom to question, to embrace ambiguity over certainty, became a cornerstone of my own abstract practice, allowing me to create works that invite multiple interpretations rather than dictate a single message. This embrace of questioning and ambiguity was indeed one of the quiet revolutions of the decade.

Take, for instance, Jeff Koons' 'Puppy' (1992), a colossal, flower-covered topiary sculpture of a West Highland White Terrier. Is it serious? Is it kitsch? It's both, playing with notions of high art and low culture, a perfect postmodern wink. Artists like Cady Noland, known for her unsettling installations that critiqued American society's fascination with crime, violence, and celebrity, often highlighted the darker side of consumerism and material excess with stark, unyielding clarity, pushing against the very narratives society held dear.

So, what exactly did postmodernism look like in practice? Here are some of its defining characteristics:

Characteristic | Description |

|---|---|

| Skepticism Towards Grand Narratives | A rejection of overarching truths or universal ideals. |

| Pastiche & Appropriation | Blending or borrowing from diverse historical styles or popular culture. |

| Irony & Playfulness | Often characterized by a self-aware, sometimes cynical, humor. |

| Deconstruction | Challenging established meanings and structures, revealing underlying assumptions. |

| Blurred Boundaries | Breaking down distinctions between 'high' and 'low' art, or different media. |

This era also sparked the much-debated "Death of Painting" conversation. With the rise of conceptual art, new media, and installation art emerging as a distinct and dominant form, many questioned whether traditional painting had lost its relevance or expressive power. The arguments for its demise often centered on the idea that painting had "done it all," exhausted its traditional forms, or was simply too traditional and static for a rapidly changing, technologically driven world that favored dynamic, interactive, or purely conceptual expressions. I distinctly remember sitting in a stuffy art history lecture, half-dozing, when a professor declared painting was dead. My immediate thought? 'Great, another thing to worry about. Is my entire future career already obsolete before it even starts? What am I even doing here, watching the demise of my chosen medium? Maybe I should switch to pottery, at least clay is undeniably physical!' It was a delightful moment of existential dread, really – a moment that, perhaps somewhat comically, propelled me to find new ways to push paint around, determined to prove that painting, in its quiet resilience, was far from its grave.

But then, proponents would counter. They pointed to its enduring tactile nature, its capacity for direct emotional expression, and its ability to adapt and absorb new influences. The resurgence of figurative painting, driven by a renewed interest in narrative and the human experience, was a significant counter-narrative to the conceptual dominance. Artists sought to reconnect with personal stories, identity, and the raw emotion that figuration could convey, often as a reaction against the perceived coldness or intellectualism of pure conceptualism. Bold new forms of abstraction and its integration into larger, immersive installations further proved its enduring adaptability. Major painters like Neo Rauch with his surreal narratives, Luc Tuymans' muted, unsettling figurative works, and even YBAs like Chris Ofili, who integrated unconventional materials into his vibrant paintings, proved that painting was far from dead. My own layered abstracts, for instance, often play with the very idea of painting's surface and depth, pushing against the canvas's perceived flatness to create a multi-dimensional experience that strongly argues against any notion of painting's demise. It was a fascinating, often heated, conversation that truly made me question the boundaries of my chosen medium. This very embrace of uncertainty, of new realities both artistic and societal, naturally led us to explore the emerging digital frontier.

The Digital Dawn: Connecting Worlds

Beyond the gallery walls, the world was shifting too. That nascent internet hum? It wasn't just background noise. I remember the dial-up screech of my first internet connection – an anthem of patience, followed by the frustrating pixelation of images loading line by agonizing line. It felt like magic, even if it was painfully slow and constantly crashing. Once, I spent an entire afternoon trying to troubleshoot a printer driver for what felt like an eternity, only for it to remain stubbornly unresponsive. Or the time I spent an entire afternoon just trying to connect to a BBS forum – success meant pixelated glory, failure meant existential dread. Pure, unadulterated frustration! My own early attempts at digital art were often just me staring at a pixelated mess, wondering if it was a profound statement or if I'd just broken Photoshop. You had to be a master of patience, or perhaps just delusion, to work with these early tools – a kind of digital stoicism, I suppose, that artists, it turns out, were uniquely equipped for. Artists embraced this pixelated reality, transforming its initial limitations into a visual language, allowing them to explore the fragmented nature of information and identity in the digital realm.

Artists were also beginning to experiment with early digital manipulation software like Photoshop (first released in 1990), nascent 3D rendering programs, and the burgeoning field of digital photography, which slowly began to challenge traditional darkroom practices, pushing the boundaries of what a photographic or painted image could be. These tools, though primitive by today's standards, offered unprecedented creative freedom. Intriguingly, their limitations – the blocky pixels, the agonizingly slow rendering times, the digital 'noise' – were often not merely tolerated but embraced and incorporated into the aesthetic of the artwork itself, becoming a distinct visual signature rather than a flaw, a digital brushstroke that defined the era.

Beyond these technical hurdles, early digital art also faced challenges related to digital preservation, the lack of established critical frameworks for new media, and issues of accessibility for artists and audiences without advanced technological resources. This decentralized spirit also manifested in early online art communities, virtual exhibitions, and digital portfolios, enabling new forms of art dissemination beyond traditional galleries. This push into the digital realm, overcoming its inherent frustrations, was undeniably a quiet revolution. Early interactive installations, hinting at the boundless, interconnected artistic universe we inhabit today, also began to emerge, further blurring the lines between the physical and virtual.

Early digital art experiments often took the form of CD-ROM art – interactive multimedia works distributed on compact discs, blurring art, games, and education. Early forays into web design as an artistic medium also began, with artists exploring the very structure of the internet browser as a canvas. Networked projects and "net art" (art made for and existing on the internet) further explored new forms of interaction and dissemination, often bypassing traditional gallery systems entirely. The medium wasn't just a tool; it was a conceptual space, allowing artists to explore ideas of digital identity, virtual communities, and the fragmented nature of information itself, even using the internet's structure as a subject for commentary on connectivity and data flow. Despite its innovative nature, early digital art often faced skepticism and resistance from traditional galleries and collectors, who struggled with its ephemeral nature, lack of physicality, and the challenge of monetization, reinforcing its status as a quiet rebellion against established norms. Artists like Olia Lialina and Alexej Shulgin pioneered this space, crafting works that were both technically experimental and conceptually rich, fundamentally challenging traditional art distribution and consumption. It was a time of pure, unadulterated excitement about a new frontier, even amidst the technical frustrations. This early digital frontier, with its promise of boundless connection, gently echoed in my own desire to create abstract works that feel interconnected and expansive, exploring the flow and fragmentation of form and color—a direct parallel to the way digital information both flows freely and breaks down into pixels.

Art as Activism: Responding to Crisis

Grunge music, with its raw, introspective mood, found a profound parallel in the art world's powerful response to the shadow of the AIDS crisis, which cast a long, poignant pall over many communities worldwide, deeply affecting the art world. Both grunge and this art channeled a raw, unfiltered angst, a disillusionment with mainstream complacency, and a directness in their emotional impact and social critique. It was a visceral outcry against silence and inaction, a testament to art's urgent role in times of widespread suffering. This urgency was further amplified by the burgeoning prominence of identity politics and queer theory (a field of critical theory, influenced by figures like Judith Butler, that challenges traditional categories of gender and sexuality) in academic discourse and broader society, which provided crucial frameworks for artists to explore issues of representation, marginalization, and collective experience through their work.

Artists like Felix Gonzalez-Torres and collectives like ACT UP and Gran Fury used their art not just to mourn, but to protest, educate, and advocate for change, injecting raw social commentary directly into the art world and public consciousness. Beyond formal gallery spaces, public art interventions and the increasingly recognized forms of street art played a vital role in this activism, bringing messages directly to communities and challenging the traditional gatekeepers of art. I remember seeing powerful, unsanctioned murals that spoke volumes more than any polished press release, a true voice from the street. The nascent digital communication of the decade, even with its slow dial-up speeds, also subtly amplified the reach of activist art, allowing messages to spread beyond physical exhibitions and into early online forums.

Beyond these immediate crises, the decade also navigated profound geopolitical shifts post-Cold War, the burgeoning forces of globalization, and early stirrings of environmental consciousness. I remember feeling a low hum of unease about the world's rapid changes, the shifting political landscapes and the growing awareness of environmental threats; it felt like the artists around me were grappling with these same complex, existential questions, trying to make sense of a world that was suddenly much bigger and more interconnected than we'd ever imagined. This period saw the nascent emergence of movements like EcoArt and BioArt, where artists began to engage directly with ecological systems and biological processes, expanding art's role as a platform for social and environmental advocacy, offering a hopeful counterpoint to the more destructive human tendencies. Think of Helen Mayer Harrison and Newton Harrison, who pioneered EcoArt, using their work to address ecological issues and propose sustainable solutions, setting a precedent for environmental engagement in art.

These elements, alongside the intense "culture wars" – particularly in the US, where debates around censorship and public funding, exemplified by controversies like the NEA Four (four performance artists whose grants were revoked amidst obscenity accusations, sparking nationwide debates over artistic freedom and government funding, fundamentally questioning the role of public art funding in a democratic society) and those involving controversial works by Robert Mapplethorpe and Andres Serrano, often made art a flashpoint. It felt like walking a tightrope between creative expression and public outrage – honestly, sometimes it felt like the art world was just looking for a good fight, and the NEA Four became unwilling gladiators in the arena of public opinion! These fierce debates, often sensationalized by the media, led to increased scrutiny of public arts funding and, for some artists, a chilling effect or even self-censorship, profoundly influencing the undertones of artistic expression and further cementing art's role in social commentary and protest. A poignant example of art directly engaging with these culture wars was Jenny Holzer's Laments series (1989-1992), powerful LED texts that addressed death, torture, and power, often displayed in public spaces, forcing uncomfortable truths into plain view amidst the societal debates.

This "culture wars" particularly made me question my own artistic boundaries – how far could I push without alienating an audience, and what was my responsibility in reflecting these societal tensions, even in abstract form? The deconstructionist ideas of post-structuralism (a broad field of thought that critiques the idea of fixed meaning or inherent truths in texts, language, and culture), for instance, made me question the very 'truths' I was trying to convey in my own abstract forms. It was like post-structuralism offered a magnifying glass to break down what we thought was solid, revealing all the tiny, shifting parts beneath – pushing me towards more ambiguous, layered compositions. It also made me wonder, with a slight chuckle, if my abstract art was secretly just a very elaborate way of saying 'I'm not sure, what do you think?' This intellectual deconstruction directly influenced my own abstract practice, pushing me towards more ambiguous, layered compositions that resist singular interpretations, inviting viewers to engage in their own process of questioning. It was a time when thinking deeply about art felt as important as making it. This profound engagement with complex social issues and critical theory marked another quiet revolution.

A Global Stage: New Voices and Market Forces

As the world shifted, so too did the very geography of the art world. The art world wasn't just centered in New York and London anymore; it was stretching its limbs globally, embracing new voices and perspectives. Cities like Berlin, Los Angeles, and even emerging art hubs in Asia such as Shanghai and Tokyo began to assert their unique artistic identities, challenging the traditional centers of gravity. This decentralization was significantly bolstered by the increasing prominence of international biennials and art fairs like the Venice Biennale, Documenta, and Art Basel, which became crucial, often the primary, platforms for showcasing non-Western artists and fostering global dialogue. These events transformed from mere exhibitions into powerful engines of discovery and market activity, fundamentally shifting power dynamics within the art world. A notable example was the Gwangju Biennale, established in South Korea in 1995, which quickly became a vital platform for showcasing contemporary art from Asia and beyond, further cementing the global shift.

I recall encountering artists like Cao Fei from China, Cildo Meireles from Brazil, or Gabriel Orozco from Mexico, whose quiet interventions challenged perceptions of everyday objects, in major Western institutions for the first time. I vividly remember the quiet awe of seeing Orozco's Yielding Stone (1992) – a perfect sphere of plasticine that collected the detritus of the city as he rolled it through the streets of New York. It was such a simple, yet profound, act that completely reshaped my understanding of sculpture and site-specificity, showing me art could be made anywhere, from anything, and challenging the grandiosity often associated with Western art. It was a real breath of fresh air that challenged the established Western canon, injecting a raw, almost audacious energy into the art scene. For me, it genuinely expanded my understanding of what art could be, shattering some of the Eurocentric biases I hadn't even realized I held – a truly humbling and eye-opening experience that made me question everything I thought I knew about 'masterpieces.'

While these biennials offered crucial platforms, it's also worth acknowledging the challenges faced by non-Western artists. These included issues of cultural translation, the potential for tokenism, and navigating a market still heavily influenced by Western preferences and the risk of exoticizing non-Western art for a Western audience. Despite these hurdles, their presence was a vital step towards a more inclusive art world. I remember feeling a strange mix of awe and mild intimidation watching them craft these monumental shows; it was like they were composing an opera, not just hanging paintings – and I was just trying to remember which continent half these new artists were from, while silently wondering if my own humble abstract pieces would ever make it to a biennial that grand!

Beyond the biennials, the increasing role of private foundations and influential collectors (beyond just Saatchi) also profoundly shaped the global art market, providing crucial funding and validation for emerging and non-Western artists, often driving new trends and tastes. The art market's resilience, even in the face of economic uncertainty, further solidified this global shift. This move towards a truly global art world was a quiet, yet seismic, revolution. I'd add here that artists like Zeng Fanzhi, a leading contemporary Chinese artist, rose to global prominence during this era, becoming one of the most significant figures in the global art market.

Simultaneously, the rise of the "star curator" further shaped the art landscape. Figures like Hans Ulrich Obrist, known for his prolific number of exhibitions and interviews, and Harald Szeemann, whose groundbreaking Documenta 5 (1972) reshaped curatorial practice by emphasizing artist-as-curator and process-based works (though earlier, his influence resonated strongly), became tastemakers. They defined exhibitions and artistic narratives in powerful new ways, often identifying emerging trends and launching careers, shifting power from traditional critics and dealers. My own encounter with a truly visionary curator, whose passion for connecting disparate ideas felt almost like magic, reshaped how I think about the presentation of my own abstract art – it’s not just about the painting, but the space and the story it tells. Sometimes, I'd even wonder if I should be trying to impress these art-world deities rather than just... making the art!

This era also saw the emergence of independent and artist-run spaces as vital counterpoints to the burgeoning commercialization and the rise of mega-galleries. Born from a strong DIY culture and a desire for artistic autonomy, these grassroots initiatives fostered experimental practices, offered alternative exhibition models, provided platforms for artists working outside the mainstream, and built communities, maintaining a crucial space for pure artistic freedom – a much-needed breath of fresh air amidst the growing market buzz. They were the unsung heroes, often operating on shoestring budgets, but providing a fertile ground where risk-taking was encouraged, and the 'cool factor' came from genuine innovation, not just market hype. It felt like a delightful, almost rebellious, counter-movement to the art market's growing roar.

Amidst this, the art market was buzzing, with figures like Charles Saatchi playing a colossal role in spotlighting artists, especially the YBAs (Young British Artists). He wasn't just collecting; he was actively transforming gallery shows into media sensations, strategically leveraging publicity to create hype and effectively setting the stage for the mega-galleries and international art fairs we know today. This era really solidified the concept of the artist as a public figure, almost a celebrity, and I remember feeling a strange mix of fascination and unease – a quiet internal debate about whether art could truly remain 'pure' when it started hitting headline news and commanding staggering prices. Was this a win for artists, or a shift that risked diluting the very essence of creation? Honestly, sometimes I still wonder if that big sale, the one that makes headlines, serves the art or just the market. It's a question I quietly wrestle with in my own studio, too.

The shifts of the 90s, from postmodern skepticism to digital horizons and a truly global perspective, laid a profound new foundation for artistic expression. These quiet revolutions didn't just change what art looked like, but how it functioned in the world, preparing the ground for the trailblazers who would define the decade's unique visual language.

Who Defined the Decade? A Glimpse at the Game-Changers

Having navigated the broad currents of change that defined the 90s – from the philosophical shifts of postmodernism to the burgeoning digital age, the urgent call for activism, and the expansion of the art world onto a global stage – we now turn our focus to the very individuals and movements who embodied these transformations. These were the game-changers, the visionaries who, whether through overt provocation or quiet contemplation, shaped the visual language of the decade, constantly blurring boundaries and challenging perceptions. It was like watching a dynamic play unfold, where each artist brought their own unique, often unsettling, energy to the stage.

The Provocateurs: Young British Artists (YBAs) and the "Sensation" Effect

So, who embodied the decade's rebellious spirit? If the 90s had a rebellious older sibling, it was probably the Young British Artists (YBAs). Remember Damien Hirst's – that shark in formaldehyde? Or Tracey Emin's confessional 'My Bed'? I remember seeing photos of that bed and thinking, 'Finally, art that understands my creative chaos!' Beyond Hirst and Emin, Sarah Lucas provocatively challenged gender and identity with her stark, often humorous self-portraits and sculptures using everyday objects. And then there was Marc Quinn, who literally froze his own blood into a self-portrait, pushing the boundaries of material and self-representation. Other notable YBAs included Jake and Dinos Chapman, known for their disturbing and often confrontational sculptures that reconfigured well-known Goya prints, and Chris Ofili, whose vibrant, often controversial, paintings integrated unconventional materials like elephant dung.

They made art feel... messy, real, sometimes uncomfortable, but always memorable. These artists pushed boundaries not just conceptually, but also in how art interacted with celebrity and the media, transforming artists into household names, or at least names loudly whispered in pub corners. Their brazen approach sometimes drew criticism, with detractors accusing them of sensationalism over substance, earning them the label of 'shock art.' The "Sensation" exhibition, for instance, sparked major controversy when it traveled to the Brooklyn Museum in 1999, drawing protests and a lawsuit from New York's then-mayor over Chris Ofili's The Holy Virgin Mary. And frankly, sometimes I had to agree – was it really art, or just a clever PR stunt, or was my art school education just too stuffy for this? I often wrestled with that question, wondering if I was just missing the point, or if the emperor truly had no clothes. It was a fascinating internal debate, trying to reconcile the visceral reaction with the intellectual justification. Yet, this very controversy, often orchestrated or amplified by figures like Charles Saatchi who masterfully leveraged media attention, fueled their impact, redefining the artist's role from studio recluse to public figure and media provocateur. This audacious redefinition of the artist's role was a true quiet revolution.

Their iconic "Sensation" exhibition in 1997, featuring pieces like Hirst's shark and Emin's bed, was a lightning rod for public fascination and debate. It felt less like a traditional art show and more like a cultural event, forcing conversations about what art is and can be.

Characteristic | Description |

|---|---|

| Shock Value | Deliberately challenging aesthetic norms and public sensibilities, often blurring lines with provocation. |

| Media Savvy | Expertly leveraging media attention to amplify presence and message, transforming artists into public figures. |

| Blurring Boundaries | Integrating everyday objects, found materials, and personal narratives, challenging definitions of 'artistic' materials. |

| Artist as Celebrity | Solidifying the concept of the artist as a recognizable public figure, often through media presence. |

I sometimes think about how much courage it must have taken to put such personal or provocative work on such a public stage – a kind of fearless authenticity I deeply admire. If you're curious about the impact of artists like Hirst, you might find more in-depth information about their legacy in guides like the ultimate guide to Damien Hirst.

Beyond the Canvas: Immersive and Experiential Frontiers

But the 90s wasn't just about painting or traditional sculpture. It was a playground for what we now call New Media and Experiential Art, with Installation Art emerging as a distinct and dominant form, transforming galleries into dynamic, all-encompassing experiences. Artists were experimenting with video, sound, computers, and immersive environments, blurring the lines between disciplines. Think of Bill Viola's profound, slow-motion video pieces like The Greeting (1995) that felt less like film and more like moving meditations, or Gary Hill's complex video installations that wrapped you in sound and image. The emergence of dedicated sound art as a distinct, though often integrated, medium added another dimension to these experiences, transforming auditory elements into central components of artistic expression. This era also saw the rise of performance art festivals, providing crucial platforms for artists to explore endurance, ritual, and audience participation beyond traditional gallery spaces.

Artists were grappling with nascent technologies, often facing steep learning curves and limited tools, yet their vision pushed forward regardless. Pioneering figures like Nam June Paik (whose influence from the 60s continued to resonate) explored video art's potential, while Jenny Holzer's text-based LED installations brought powerful, often unsettling messages into public spaces, forcing interaction. It was art that demanded your presence, your full immersion, often playing with light, space, and time in ways static art couldn't. A significant challenge for these ephemeral works was documenting and preserving them for future generations, a problem that continues to vex curators and art historians today.

Characteristic | Description |

|---|---|

| Immersive Environments | Creating a space the viewer physically enters and experiences. |

| Multi-Sensory Engagement | Often incorporating light, sound, video, and sometimes even scent or touch. |

| Site-Specific | Designed for a particular location, interacting with its architecture or history. |

| Ephemeral Nature | Many installations are temporary, existing for the duration of an exhibition. |

Rachel Whiteread, for example, gained prominence for her haunting cast sculptures of architectural interiors or the undersides of objects (like House, 1993), transforming negative space into solid forms and imbuing absence with presence – a truly immersive and thought-provoking approach that went beyond the visual. Even artists like Yayoi Kusama, whose work spanned decades, contributed to this immersive shift with her iconic Infinity Rooms, creating environments that enveloped the viewer in a dizzying sense of endless repetition and contemplation. I remember feeling a bit overwhelmed by some of these works, yet totally captivated. It was a fascinating shift, almost like the art itself was asking, 'Are you just looking, or are you experiencing?'

Stepping into Bill Viola's The Crossing (1996), for instance, and being engulfed by fire and water, made me profoundly rethink the boundaries between art and experience. It influenced my own desire for abstracts that invite viewers to get lost in their own perceptions, not just observe from a distance.

It was like stepping into someone else's carefully constructed world, a premonition of the digital age to come, and it made me consider how my own art, though abstract, could create immersive experiences for the viewer. I strive for a similar sense of immersion in my own abstracts, using interweaving lines that guide the eye, shifting hues that create illusions of depth, and tactile surfaces that invite touch, all designed to draw the viewer in, inviting them to get lost in the forms. Getting these large, unconventional pieces accepted by traditional galleries and collectors, who were often still focused on easily sellable objects, was a quiet rebellion in itself because they resisted easy commodification and challenged the notion of art as a fixed, transportable object, truly embodying the decade's spirit of 'quiet revolutions' in artistic experience.

The decade also saw a significant evolution in performance art, with artists pushing the boundaries of the body and ephemeral experiences. Matthew Barney, for instance, began his epic Cremaster Cycle in the 90s, a complex series of films and sculptures that blended personal mythologies with stunning visuals and often extreme physical feats. And the powerful influence of artists like Marina Abramović, who had been challenging the limits of performance since the 70s, continued to inspire a new generation to explore endurance, ritual, and audience participation as core artistic elements, further solidifying performance as a potent, boundary-pushing medium.

Perhaps surprisingly, with all these new forms emerging, the role of art criticism itself was undergoing its own quiet revolution (or perhaps, a crisis of identity). How could traditional critics grapple with ephemeral installations, interactive digital works, or highly conceptual pieces that defied easy categorization or traditional aesthetic judgment? The 90s saw critics struggling to establish new frameworks for evaluating art that prioritized experience and idea over form and object, leading to ongoing debates about relevance and critical authority in a rapidly expanding art world.

Echoes of Raw Energy: Basquiat's Legacy and Street Art's Ascent

Beyond the screen and immersive installations, this era saw a powerful resurgence of art that thrived outside traditional institutions, drawing raw energy from the streets and channeling it into bold new forms. While the peak of Neo-Expressionism was in the 80s, the raw, almost visceral energy it embodied, along with the powerful legacy of artists like Jean-Michel Basquiat, loomed large over the 90s. Graffiti and street art, which had emerged as powerful counter-cultural forces in the 1970s and 80s, continued their evolution into more recognized forms in the 90s, often influenced by the rhythmic energy of hip-hop culture.

His work, with its cacophony of brilliant thoughts and jazz-like rhythms, continued to inspire a generation to embrace bold, unapologetic strokes and raw, emotionally charged narratives, often influenced by graffiti and street art. Basquiat’s unique fusion of urban graffiti, abstract expressionism, and political commentary provided a powerful blueprint for artists exploring identity, racial injustice, and societal power structures with unfiltered authenticity. His significant market success, which only continued to grow posthumously throughout the 90s, firmly cemented the commercial viability of raw, street-influenced art, proving that profound artistic statements could emerge from unexpected places. It was a reminder that art could be both deeply personal and universally resonant. The raw, unpolished energy of his lines always resonated with me, inspiring a similar fearless embrace of imperfection and spontaneity in my own abstract process – allowing the art to breathe and show its own history of creation. The persistent influence of this raw energy was a crucial, albeit quiet, revolution.

Beyond Basquiat, the influence of street art and graffiti continued to permeate the mainstream. The 90s witnessed their significant evolution from subversive counter-cultural acts into increasingly recognized and accepted art forms, even gaining traction through early street art festivals and a slow but steady institutional recognition as a legitimate art movement. I remember stumbling upon a vibrant mural in an unexpected alleyway once, a burst of defiant color that felt more alive than anything I’d seen in a pristine gallery. It was an art that insisted on being seen, not just admired behind glass. Pioneering figures like Futura 2000 and Dondi White, whose vibrant wildstyle graffiti evolved into gallery-worthy abstractions, further solidified this transition. Artists like Barry McGee (aka Twist) in San Francisco or Shepard Fairey (who started his 'Obey Giant' campaign in '89, gaining momentum through the 90s) brought urban aesthetics and stencil art into wider public consciousness and eventually galleries, further blurring the lines between high art and street culture. This raw, untamed energy, often created anonymously or collaboratively, challenged traditional notions of authorship and exhibition spaces. However, this transition also sparked ongoing debates about the commercialization of street art – whether it loses its edge when brought indoors or becomes a commodity, a question I still ponder when I see a tag on a canvas in a white-cube space. And then you have Christopher Wool, who took that urgency and channeled it into these incredible word paintings and patterned abstractions. His 'pattern paintings' from the late 80s and 90s, those slightly messy, almost industrial patterns or stenciled words, felt like the perfect visual counterpart to the grunge music I was listening to. It was rough, real, and totally captivating. I sometimes stare at his work and feel like it's challenging me, urging me to strip away my own artistic pretensions and embrace the raw, unfiltered truth in my abstract forms. It's like he's asking, 'Are you brave enough to be this unpolished, this direct?' – a question that constantly echoes in my own studio as I try to push past perfectionism into genuine expression.

Even the enigmatic figure of Banksy, though rising to global prominence later, laid some of his foundational groundwork in the guerilla street art scene of the 90s, pushing boundaries of public intervention and social commentary with his impactful stencils.

If you're as fascinated by his unique approach as I am, you might want to dive deeper into the ultimate guide to Christopher Wool.

Photography and Narrative: Shifting Lenses

How did photography capture the shifting realities of the 90s? The decade solidified photography's place as a powerful conceptual medium. This era witnessed its significant shift from purely documentary work to large-scale, often staged or manipulated compositions, challenging traditional notions of photographic truth and reality itself. Artists like those from the Düsseldorf School – including Andreas Gursky and Thomas Struth – created vast, highly detailed photographs of contemporary society, transforming everyday scenes into monumental statements. Similarly, Wolfgang Tillmans captured candid, often intimate scenes of youth culture, nightlife, and queer life, blurring the lines between art and documentary, pushing the boundaries of photographic aesthetics and its capacity for social commentary.

This period also saw the rise of staged photography or tableau photography, where artists meticulously constructed elaborate scenes for the camera, moving away from purely capturing reality to actively creating it. This approach highlighted the constructed nature of images and narratives. Alongside this, a powerful counter-current emerged in documentary photography with a more personal, subjective lens. Artists like Nan Goldin, renowned for her raw, unflinching series The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, offered intimate glimpses into subcultures and personal relationships, using photography as a tool for empathetic storytelling and social critique, rather than objective reportage. Amidst this evolving landscape of photographic inquiry, other artists explored personal and political narratives through different mediums, often with a profound focus on identity, loss, and social commentary.

The Personal & The Political: Identity, Body, and Craft

What truly defines us, and how does art reflect that quest? Identity Art was a massive theme, profoundly influenced by the growing prominence of identity politics and queer theory (a field of critical theory, influenced by figures like Judith Butler, that challenges traditional categories of gender and sexuality) in academic discourse and broader society. This provided crucial frameworks for artists to explore issues of representation, marginalization, and collective experience through their work. The traditional divide between "fine art" and "craft" also began to blur, with artists like Kiki Smith pushing boundaries with her sculptures exploring the body and nature through diverse materials including textiles, and Ghada Amer gaining recognition for her embroidered paintings that challenged notions of female identity and beauty. This shift meant textiles and ceramics gained increasing recognition as legitimate artistic mediums within the gallery space. The influence of postcolonial theory (often associated with thinkers like Edward Said) also grew significantly, providing a critical lens for artists to explore themes of cultural identity, historical power imbalances, and the legacies of colonialism, especially as the art world became more global. I recall early art school days where 'craft' was almost a dirty word, separate from 'real' art, and then suddenly, artists were making profound statements with thread and clay. It was a delightful, almost rebellious, re-evaluation that, I admit, initially made me a little uncomfortable – my art was serious, on canvas! – but eventually made me question my own ingrained biases about materials. What a snob I must have been, dismissing the tactile magic of fiber arts or ceramics! This blurring of boundaries between so-called 'fine art' and 'craft' deeply resonates with me, as my own abstract work often plays with textured layers and unconventional materials to challenge the perceived flatness of the canvas, pushing against traditional notions of painting. This quiet re-evaluation of mediums and materials was a powerful shift.

Cindy Sherman continued her groundbreaking work, using herself as a chameleon to explore stereotypes and gender roles. I sometimes wonder what persona she'd adopt if she were documenting my morning routine – probably a very tired, coffee-craving one, trying to figure out which sock matches which, or perhaps a bewildered one trying to decipher my own abstract doodles before the caffeine kicks in! Her ability to transform, yet remain critically observant, mirrored my own fascination with how different perspectives can alter the 'reality' of a piece, inspiring me to create abstracts that shift and reveal new forms with each viewing angle. It's like her work whispers, 'Look closer, there's always more than one story here.'

And then there's Felix Gonzalez-Torres, whose minimalist yet profoundly moving works offered a deeply personal and political commentary, particularly on the AIDS crisis and loss. His "candy spills" – piles of individually wrapped candies that viewers were invited to take – often represented the ideal weight of his partner, Ross Laycock, who died of AIDS-related complications. As candies are taken, the pile diminishes, symbolizing the inevitable process of loss, but also the enduring power of love and memory through shared experience. It was art that wasn't just seen, but felt, participated in, and profoundly internalized – a truly unique approach that radically shifted my own understanding of what an artistic 'object' could be, emphasizing shared experience over static form. For more on how artists grapple with profound grief and remembrance, you might explore works categorized under art about loss. This relational and deeply personal approach was a profound quiet revolution. While often deeply impactful, some identity-based art occasionally faced criticisms of being overly didactic, too niche, or essentialist, but artists continually found nuanced ways to transcend these perceptions, using specificity to reach universal truths.

Beyond these giants, Kara Walker challenged perceptions of race, gender, and history through her provocative cut-paper silhouettes, often depicting unsettling narratives from the antebellum South. Glenn Ligon explored themes of race, language, and sexuality, often using text-based paintings that blurred and obscured words, forcing a contemplation of identity and visibility. And Shirin Neshat examined the complexities of identity, gender, and Islamic culture through her powerful photography and video installations. Feminist artists, building on the foundations of previous decades, continued to evolve their practice, with figures like Mona Hatoum exploring themes of displacement, body, and surveillance through unsettling installations and performances, or Janine Antoni challenging notions of domesticity and female labor through unique, process-based sculptures. These artists, each in their unique way, pushed the boundaries of narrative and representation, inviting viewers to grapple with multifaceted identities and societal norms.

Challenging Institutions: Critique & Relational Aesthetics

What happens when art turns its lens on its own structures? Another significant, albeit quieter, development of the 90s was the rise of Institutional Critique and Relational Aesthetics. Artists engaged in Institutional Critique, like Andrea Fraser or Fred Wilson, directly questioned the power structures, biases, and historical narratives upheld by museums and galleries, often through performances or re-installations that highlighted their inherent complexities. For instance, Fred Wilson's Mining the Museum (1992) rearranged a historical society's collection to expose racist and classist narratives embedded in their displays, forcing a profound re-evaluation. I always found it wonderfully subversive, like someone secretly rearranging the museum labels to tell the real story. What a delightful, intellectual mischief! It certainly made me think about how even my own art, though abstract, could subtly challenge expectations about what's "gallery-worthy" or how it should be presented – maybe someday I'll arrange a whole exhibition of my abstract works in a grocery store, just to see what happens! (Though I'm not sure the grocery store manager would be as thrilled as the art critics, or if the bananas would really complement my blues. The logistical nightmare alone makes me chuckle!)

Simultaneously, Relational Aesthetics, pioneered by artists like Rirkrit Tiravanija, emphasized social interaction and shared experiences over the creation of physical art objects. Tiravanija, for example, would often cook and serve food in gallery spaces, transforming the viewing experience into a communal event. Think of it like a pop-up dinner party where the meal is the art, breaking down the traditional barrier between observer and artwork. While groundbreaking, Relational Aesthetics sometimes drew criticism for being too ephemeral, too focused on the social event rather than a tangible art object, or even exclusive to those physically present. Despite these debates, it was art that wasn't just about what you saw, but what you did and who you interacted with, further blurring the lines between art and life, and aligning perfectly with the decade's embrace of experiential forms. This felt like a subtle, yet powerful, challenge to the traditional art market because, by focusing on experiences rather than sellable objects, it poked a delightful hole in the idea that art must be a tangible, commodifiable 'thing.' The long-term impact of institutional critique is evident in how many museums today actively engage with diverse narratives, re-evaluate their collections, and strive for greater transparency and inclusivity, though the journey is far from over. It definitely made me rethink how my own art could connect with viewers on a deeper, more participatory level, beyond just visual appreciation. This focus on process and interaction was a truly quiet revolution in how art could function.

The Quiet Contemplatives: Serenity Amidst the Clamor

Amidst the sensationalism and bold declarations of many 90s movements, there were also quiet counter-currents – artists who continued to explore more minimalist, conceptual, or abstract veins. These artists often sought a different kind of rebellion, a return to introspection and fundamental questions. Their motivations were varied: for some, it was a direct reaction to the perceived excess and bombast of the 80s, for others, a subtle counterpoint to the media-driven sensationalism of the YBAs, and for many, a deeper, more personal search for meaning, even a spiritual one, beyond the clamor of the art market. They offered a 'quiet rebellion' by prioritizing internal reflection and nuanced perception over shock value or market trends. Think of artists like Roni Horn, whose work often involved subtle explorations of identity and nature through precise installations and photographs, or Wolfgang Laib, with his meticulously arranged natural materials like pollen or milk, offering a serene, almost spiritual contrast to the decade's louder, more confrontational statements. The continued relevance of Light and Space artists like James Turrell and Robert Irwin also provided a contemplative counterpoint, with their profound explorations of perception through light, space, and immateriality, influencing a subtle strain of artistic introspection. Furthermore, the enduring appeal of Minimalism and Post-Minimalism continued to resonate, with artists revisiting their core tenets of material specificity, geometric abstraction, and the relationship between art object and viewer, often with renewed spiritual or philosophical undertones.

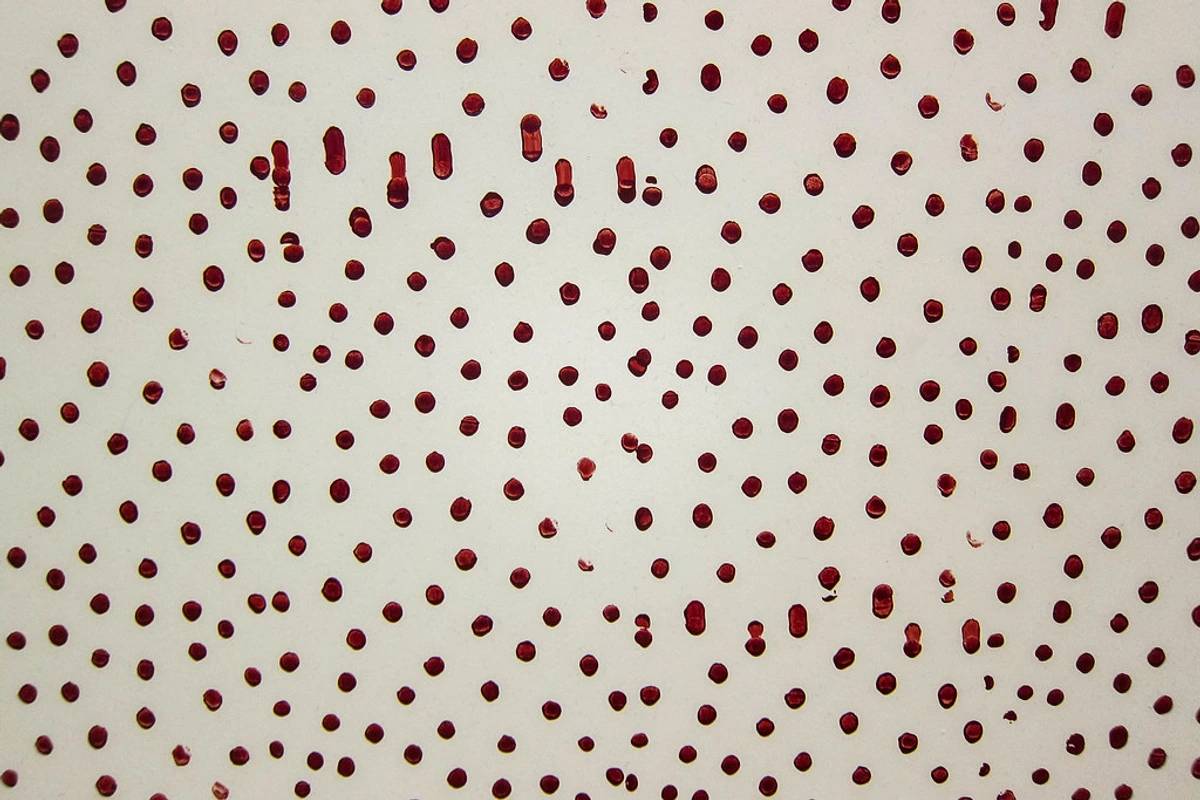

And then there's Gerhard Richter, whose continued exploration of abstract painting and photographic works, often blurring the lines between representation and abstraction, offered a profound sense of contemplation and skepticism towards objective truth, even amidst the decade's clamor. Richter's ability to imbue his abstract works with such depth and emotion, often through seemingly simple color fields or blurred forms, was a constant source of quiet inspiration for me, proving that profound artistic statements could be made in a whisper, a subtle invitation to pause and look closer, rather than a demand for attention. His work, like his iconic 1024 Colors (1973), with its precise yet chaotic grid, is a masterclass in controlled chaos, something I constantly strive for in my own layering.

This era also saw a quiet resurgence and re-evaluation of painting through artists like Peter Doig, whose lush, almost dreamlike figurative landscapes garnered significant attention, demonstrating painting's enduring power to evoke deep emotion and memory. His work, often infused with a sense of melancholic quietude, stood in subtle contrast to the YBAs' more confrontational style, further proving that painting was far from dead and still held immense capacity for 'quiet revolutions' in perception. These works, often deeply contemplative, served as quiet anchors in a decade of rapid change. For me, they resonated deeply, a quiet rebellion against the clamor, reminding me that profound artistic statements could be made in a whisper, a subtle invitation to pause and look closer, rather than a demand for attention. I distinctly remember one afternoon, feeling overwhelmed by the endless noise of the world, and coming across a Peter Doig print that just... stopped me. It was a moment of pure, unexpected calm, a visual breath that I now try to infuse into my own work.

My own work, with its subtle color shifts and layered textures, aims for that same quiet invitation, a space for pause amidst the visual noise.

Key Takeaways: Distilling the 90s Art Scene's Essence

So, after all that, what truly defined this decade for me? To distill the essence of this complex period, here are its defining characteristics:

Trait | Key Concept | Description | Example/Artist |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quiet Revolutions & Boundless Adaptability | Subtle Transformation | A decade defined by subtle, internal shifts in artistic thought and boundless adaptability, often redefining rather than overtly declaring. | Felix Gonzalez-Torres' "candy spills" invited participatory deconstruction of art objects, a quiet subversion. |

| Conceptual Depth | Idea Over Aesthetics | Art was less about aesthetic beauty and more about ideas, challenging viewers to think, question, and engage intellectually. | Damien Hirst's shark (The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living) questioned life, death, and art's boundaries, forcing intellectual debate. |

| Blurred Boundaries | Interdisciplinary Fusion | Distinctions between traditional art forms (painting, sculpture) and new media (video, digital, installation) dissolved, as did the lines between 'high art' and 'low culture.' | Jeff Koons' 'Puppy' blurred fine art with kitsch and public spectacle; Bill Viola's video installations merged film, performance, and immersive environments. |

| Personal and Political | Identity & Activism | A strong emphasis on identity, social commentary, and activism, reflecting broader societal shifts and 'culture wars.' | Cindy Sherman's photographic self-portraits deconstructed gender roles, while Gran Fury's public art addressed the AIDS crisis with urgent directness. |

| Globalization | Decentralized Art World | The art world expanded beyond Western centers, fostering diverse perspectives and challenging traditional artistic hierarchies. | The Gwangju Biennale (1995) provided a crucial platform for non-Western artists like Cao Fei, shifting the art world's geographical focus. |

| Market Influence | Commercialization & Hype | The increasing commercialization and media spotlight on artists transformed the art market into a global industry. | Charles Saatchi's role in promoting the YBAs, culminating in the "Sensation" exhibition, cemented the artist-as-celebrity phenomenon and magnified market speculation, anticipating today's mega-galleries. |

These traits, woven together, created a period of profound transformation that continues to shape the contemporary art landscape. But how exactly do these ripples manifest today, and what echoes can we still hear?

The 90s Legacy: Shaping Today's Canvas

So, what did all this messy, beautiful complexity leave us with? Looking back, the 90s art scene wasn't just a fleeting moment; it was a foundational period that continues to ripple through contemporary art, its quiet roar still echoing in the galleries and studios of today. The emphasis on conceptual art, the blurring of disciplinary boundaries, the exploration of identity, and the embrace of new media technologies—these are all hallmarks of art being made today.

Artists of the 90s, particularly the YBAs, redefined the relationship between art, media, and public spectacle, setting a precedent for artist-as-celebrity and the sensationalized art event. Their fearlessness in tackling controversial subjects paved the way for more open discourse in the art world. This era also profoundly intensified the commercialization of art, transforming a niche market into a global industry driven by soaring prices, mega-galleries, and the solidification of the art fair circuit as a central force, impacts we feel acutely today. Of course, this increased commercialization also had its downsides, leading to concerns about art being treated purely as an investment rather than for its cultural value, and contributing to market bubbles.

The discussions around "star curators" also contributed to the rise of curatorial studies as a distinct academic and professional field, emphasizing exhibition-making as an artistic practice in itself. The 90s also significantly laid the groundwork for the democratization of art creation, as increasingly accessible digital tools lowered barriers to entry, enabling more independent artists and online platforms to emerge, a phenomenon we fully experience today.

The decade also saw the increasing global decentralization of art, moving beyond the traditional Western capitals to embrace diverse perspectives. This shift, facilitated by international biennials and the rise of a global art market, fostered a more inclusive art world, reflecting the complex interconnectedness of our times. The nascent digital experiments of the 90s blossomed into the vibrant landscape of digital art, AI art, and virtual reality experiences we see dominating conversations now – indeed, the very concept of NFTs can be traced back to the early net art experiments in decentralized art and digital ownership. Beyond this, the 90s laid the groundwork for the rise of social practice art, emphasizing community and interaction; the continued evolution of performance art, pushing boundaries of endurance and engagement; and a sustained focus on intersectional identity politics, recognizing the complex layers of human experience. The issues of identity, memory, and political engagement that resonated so strongly in the 90s are still fiercely relevant, perhaps even more so, driving much of the art that inspires me today. This profound legacy sets the stage for the resounding echoes we continue to hear in today's artistic landscape. The 90s also provided an early glimpse into the "experience economy," where value is increasingly placed on memorable experiences rather than mere possession of objects, a trend now ubiquitous in many sectors, proving art's predictive power.

Conclusion: A Quiet Roar That Still Echoes

The 90s, for me, was a decade of quiet revolutions. It wasn't about grand, sweeping movements, but rather a profound, often messy, and deeply personal unraveling and reweaving of what art could be. From Hirst's audacious shark to Gonzalez-Torres' poignant candy spills, from the raw energy of Basquiat’s legacy to the introspective personas of Cindy Sherman, and the quiet contemplations of Gerhard Richter and Peter Doig, the art of the 90s challenged, provoked, and invited us to look deeper.

It was a time when artists embraced vulnerability, questioned authority, and fearlessly explored the fringes, all while the world was quietly, rapidly changing around them. This era profoundly shaped my own artistic journey. The 90s taught me to chase the beauty in the delightfully odd, to find meaning in abstraction that can feel both deeply personal and universally resonant, and to appreciate art that dares to be messy, real, and uncomfortable. My own colorful and abstract works, with their delightfully chaotic layered textures, the whisper of brushstrokes barely visible beneath a bold splash of color, and unexpected color combinations, often draw on this very spirit of introspection and transformation, aiming to create immersive experiences that challenge perceptions, much like the YBAs challenged traditional aesthetics with their audacious choices. The 90s didn't just build a bridge between eras; it laid a new foundation for artistic freedom, a framework that still supports and inspires the art being created today.

If you're curious to see how this 'quiet roar' manifests on canvas, my prints and paintings are available for sale. You can also see more about my journey and influences at my artist timeline or visit my museum in 's-Hertogenbosch, NL if you're ever in the neighborhood. The echoes of the 90s — its raw honesty, its questioning spirit, its boundless experimentation — still reverberate in the contemporary art world, continuing to evolve and inspire future generations. It was a decade that began with a whisper but left a roar that truly shapes my canvas and, perhaps, yours too.