The Philosophy of Aesthetics: Why Art Moves Us and How We Experience Beauty

Have you ever stood before a painting, perhaps something wildly abstract, and just... felt it? Not understood it intellectually, mind you, but felt a tug, a resonance, a quiet hum in your soul? I've been there countless times, both as an observer and, rather embarrassingly, as the creator of the very chaos that sometimes elicits such responses. It's a curious phenomenon, this pull towards certain arrangements of color and form, isn't it? This isn't just about 'liking' a nice picture; it's about something far deeper, something that taps into the very wiring of our human experience – our capacity for aesthetic judgment, our inherent ability to perceive, appreciate, and evaluate beauty and art. This, my friends, is where the vast and wonderfully puzzling world of the philosophy of aesthetics steps in.

Today, I want to pull back the curtain on this intriguing subject, not as a dry academic lecture (heaven forbid!), but as a fellow human trying to make sense of why a splash of paint on a canvas can move us to tears or fill us with joy. We'll explore ancient ideas, modern perceptions, various aesthetic theories, and even the sublime, all through the lens of my own messy, wonderful journey with art and a few philosophical detours.

The Age-Old Question: What is Beauty?

For centuries, philosophers have wrestled with the concept of beauty. Is it objective, like the laws of physics, existing independently of us? Or is it entirely subjective, residing solely in the eye of the beholder, a mere preference like my inexplicable love for burnt toast? (Don't judge, it's a texture thing!)

Ancient Greek thinkers like Plato saw beauty as a reflection of ideal Forms, a glimpse of perfect, unchanging truths, existing in a realm beyond our senses. Beauty, for Plato, was an ultimate, objective reality. Aristotle, while also acknowledging objective qualities, grounded his view more in the material world, focusing on properties like order, symmetry, and definiteness as sources of beauty. He was less concerned with a transcendent "Form" and more with the inherent structure and harmonious arrangement within the object itself.

Fast forward to the Enlightenment, and Immanuel Kant introduced the idea of "disinterested pleasure" – a judgment of beauty that isn't tied to personal desire or utility. For Kant, when we call something beautiful, we are not judging it based on personal preference or usefulness, but rather on its form, independent of any concept or purpose. It's a high bar, this 'disinterested pleasure,' making me wonder if Kant ever truly lost himself in a piece without a tiny flicker of personal bias, or if he was just really good at pretending. Still, it suggests a shared human capacity for appreciating form for its own sake, something beyond just 'I like it' or 'I don't.' Later, David Hume, an empiricist, emphasized that beauty is a "sentiment" – a feeling or emotion evoked in the observer, asserting that "beauty is no quality in things themselves; it exists merely in the mind which contemplates them." This highlights the deeply subjective component, even while acknowledging shared human nature might lead to common aesthetic responses.

Beyond these foundational figures, others have added layers to the debate. G.E. Lessing, for example, distinguished between the spatial arts (like painting, best for depicting beauty in a single moment) and temporal arts (like poetry, better suited for action and narrative), hinting at how the medium itself shapes our aesthetic experience. And for Arthur Schopenhauer, art offered a temporary escape from the incessant striving of the human will, a moment of pure, detached contemplation, which, let's be honest, sounds pretty appealing on a Monday morning.

While certain universal principles of balance, harmony, and proportion might indeed have a foundational, almost innate appeal (think of the mesmerizing symmetry in a snowflake, the golden ratio in art, or the comforting cadence of a musical harmony), our individual experiences, cultural backgrounds, and emotional states play a colossal role in what truly moves us. This constant interplay shapes our 'aesthetic judgment'—the capacity to discern, appreciate, and evaluate beauty. It's a skill we refine over time, influenced by exposure, education, and even our developing emotional intelligence. And often, beneath the surface, there's an appreciation for the skill and craftsmanship involved, the sheer human effort that brings a vision to life, whether it's a perfectly rendered classical sculpture or the deliberate chaos of an abstract masterwork, a visual harmony often meticulously composed beneath the apparent chaos.

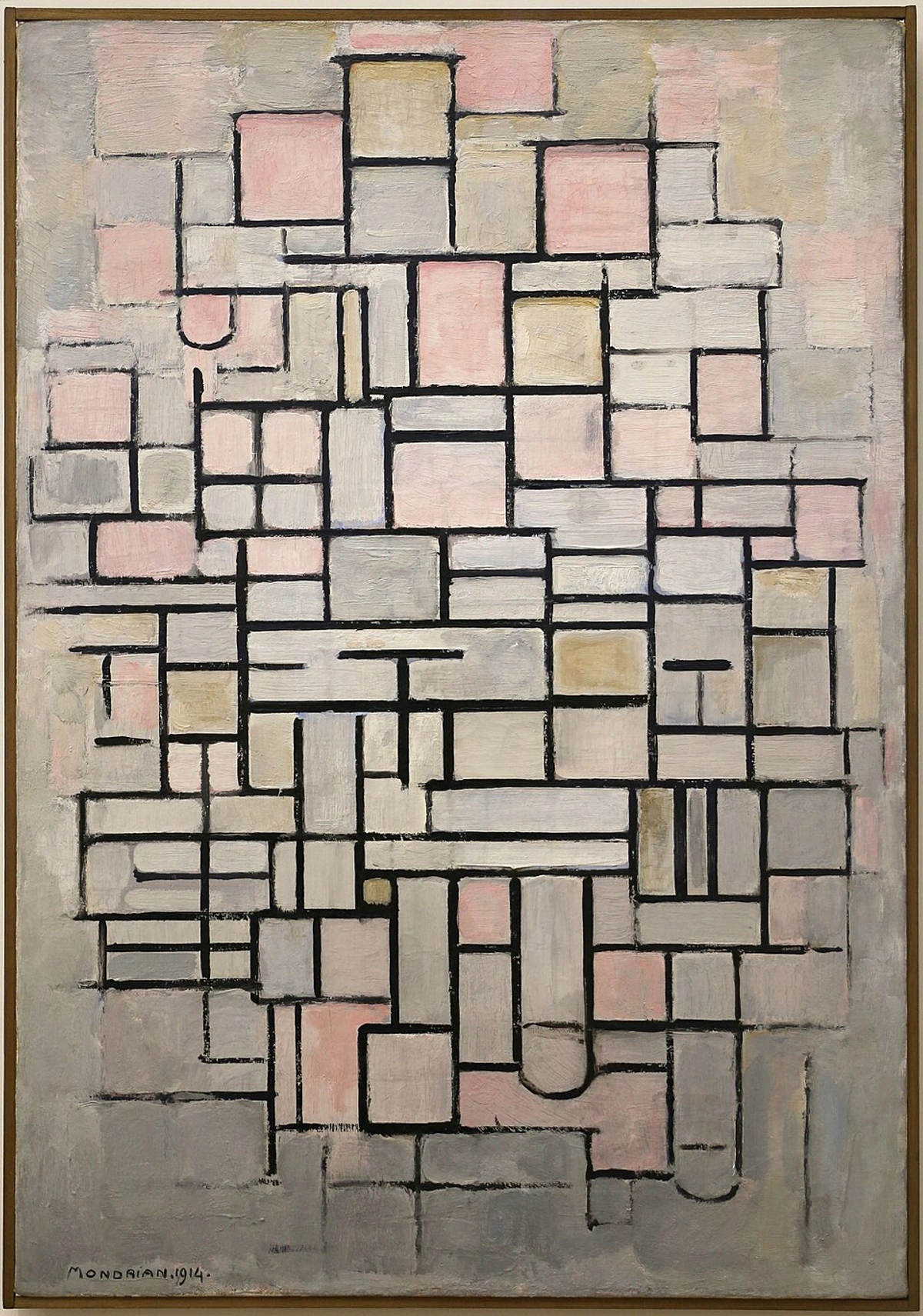

Consider also the Institutional Theory of Art, which posits that something becomes art because the "art world" (critics, galleries, museums, artists) deems it so. While a bit cynical, it reminds us that our experience of beauty and art is often framed and validated by cultural authorities. On the flip side, Formalism argues that the aesthetic value of art lies solely in its formal qualities – the lines, shapes, colors, and compositions – independent of its subject matter or narrative. This is where a minimalist Rothko or a complex Mondrian finds its power. Speaking of which...

Take, for instance, a classic like Henri Matisse's "The Red Room" (Harmony in Red). It's vibrant, bold, and undeniably striking. For a deeper dive into this master, check out our ultimate guide to Henri Matisse.

The sheer audacity of the red, the flattened perspective – it challenges conventions, yet it sings with a unique harmony. Some might find it exhilarating; others might find it jarring. Neither is wrong. This dance between objective elements and subjective reception is where the magic truly unfolds, reminding us that art's power often lies in its capacity to provoke diverse, yet equally valid, responses. It speaks to the incredible diversity of human perception, highlighting why the search for a singular definition of beauty is ultimately less fruitful than embracing its multifaceted nature. It's this very diversity that, as an artist, I aim to tap into, moving beyond mere representation to evoke pure feeling.

The Emotional Language of Art: A Creator's Perspective

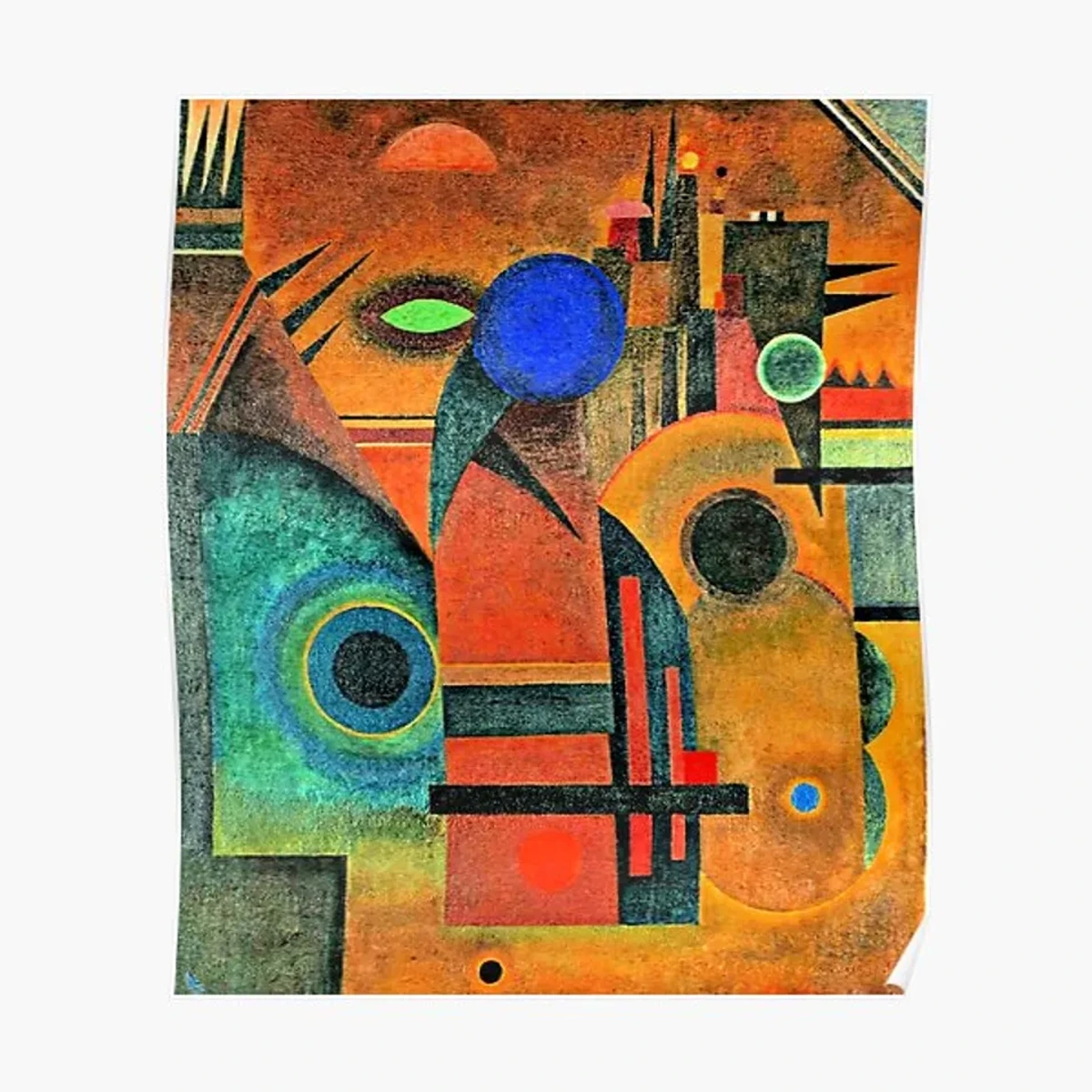

Having wrestled with what beauty is from a philosophical standpoint, let's talk about what it feels like, especially from my side of the easel. For me, as an abstract artist, beauty isn't always about a perfect representation of reality. It's often about the raw, unfiltered emotional communication that bypasses the intellect entirely. It's about how colors clash and merge, how textures invite touch, how lines dance across the canvas. It's the emotional language of color speaking directly to your subconscious.

Beyond my personal palette, the psychology of color in general offers fascinating insights. Think of the visceral impact of reds that stir passion or blues that soothe and deepen reflection. Each hue carries its own psychological weight, and understanding these associations, even intuitively, allows for a more potent connection. My own palette and story are deeply intertwined with these chromatic conversations.

I've spent countless hours in my studio, often with music blaring, just letting my intuition guide my brush. It's a process of listening, not just to the music, but to the canvas itself – observing how colors interact, how lines suggest movement, how forms emerge, almost guiding my hand. It's a dialogue, a dance of intuition and material – a kind of intuitive painting. When I create a piece, I'm not trying to dictate exactly what you should feel, but rather to open up a space for feeling. That moment when someone looks at one of my pieces and says, "I don't know why, but I love it," that's aesthetics in action. That's the magic. And to those who sometimes say, "Abstract art is meaningless" or "Anyone could do that," I simply invite them to try. Beneath the apparent chaos lies a rigorous understanding of composition, color theory, and an often intense emotional and intellectual process that can take years to hone.

Key Aesthetic Concepts at Play

But how do we begin to unpack this complex interplay of art and our perception? It's less about finding a single key and more like understanding the different threads woven into a rich tapestry of experience. Let's briefly touch upon some big ideas that help us understand this dance:

Sensory Engagement: The Primal Pull

This is the immediate, almost primal delight we get from certain visual, auditory, or tactile stimuli. Bright colors, smooth textures, symmetrical forms – these often trigger positive responses. Think of the visceral satisfaction of a vibrant Gerhard Richter abstract painting – the sheer texture can be mesmerizing. I remember once, standing before one of his larger squeegee pieces, feeling an almost physical urge to run my fingers across the thick layers, a purely primal, non-intellectual delight. It's a direct connection, a whisper from the art to your senses.

Beyond just pleasure, our brains are wired to respond to art. Concepts like mirror neurons suggest we literally 'mirror' the actions or emotions depicted, fostering empathy. Emotional contagion means we can catch emotions from a piece, feeling sorrow from a somber painting or joy from a vibrant one, often without conscious thought. These are the subtle, automatic ways art bypasses our intellectual defenses and goes straight for the gut.

Cognitive Interpretation: Unpacking Meaning

Beyond the immediate sensation, we seek meaning. This is where our brains kick in, trying to decode what abstract art is telling us. Sometimes, the beauty lies in the intellectual challenge or the profound narrative we uncover, even if it's deeply personal. This process is less about finding 'the' correct meaning and more about the active engagement of our minds, shaping our own aesthetic judgment. It's a bit like Roland Barthes’ 'The Death of the Author' idea: once I put a piece out there, its meaning isn't solely dictated by what I intended, but by what you, the viewer, bring to it.

We also engage with art through aesthetic distance – that subtle psychological separation that allows us to contemplate a work without being overwhelmed by its practical implications or immediate desires. It's about stepping back, mentally, to appreciate the art for its own sake, rather than, say, seeing a portrait and worrying if the person looks like your ex (we've all been there, right?). Without this distance, we might react purely instinctively, missing the deeper artistic intention or formal qualities.

Our perception is also guided by Gestalt principles – how we naturally organize visual information into coherent wholes. We look for patterns, proximity, similarity, and closure, unconsciously trying to make sense of the visual symphony before us. This cognitive process is fundamental to how we construct our aesthetic experience.

Emotional Resonance: Connecting with Feeling

Art can evoke powerful emotions – joy, sorrow, awe, anger. A piece isn't just beautiful because it's visually pleasing, but because it connects us to a shared human experience, mirroring our own feelings or opening us to new ones. Psychologically, artists often harness elements like specific color palettes (think the somber blues of a Picasso or the joyful yellows of a Van Gogh) or compositional techniques (like leading lines for drama or balanced forms for serenity) to guide these emotional responses. This is particularly potent in expressive works, where the artist's raw emotion seems to seep from the canvas, bypassing the intellect entirely and speaking directly to the heart. This is also why abstract art, which often eschews literal representation, can be so profoundly moving; it leaves space for your own emotional landscape to meet the artist's.

![]()

Contextual Influences: Culture, History, and Perception

What is considered beautiful shifts across cultures and time. A ceremonial mask from one tradition might be seen as profoundly moving, while in another context, it might be viewed as unsettling. Even within my own artistic journey, evolving through different phases, you can see a reflection of changing influences and personal growth – how I've absorbed and reacted to the aesthetics of my environment and experiences.

Consider, for example, the intricate, often challenging beauty of Indigenous Australian dot paintings, whose meaning and aesthetic impact are deeply embedded in specific cultural narratives and spiritual beliefs, far removed from Western artistic traditions that often prioritize literal representation. Or the serene, minimalist beauty of a Japanese Zen garden, where every rock and raked line is a deliberate invitation to contemplation. Beyond this, the very form of art—how elements like lines, shapes, colors, and textures are arranged and composed—plays a crucial role. Whether it's the stark minimalism of a Rothko or the intricate patterns of a Persian rug, the arrangement itself can evoke a distinct aesthetic experience, regardless of explicit narrative. It's the visual grammar that structures our perception.

It's a lot to take in, isn't it? These aren't neat little boxes, but interwoven threads, constantly pulling at our perceptions. Sometimes, I wonder if the best aesthetic experience is simply embracing the beautiful mess of it all. What do you think?

Artist's Intention vs. Viewer's Perception

This brings us to another fascinating aspect of aesthetics: how much does the artist's original intent matter? As a creator, I infuse my work with my own emotions and ideas, but I also know that once it leaves my studio, it takes on a life of its own. A viewer might see a color combination I chose for joy and interpret it as sorrow, or find a shape I created intuitively as a symbol of something deeply personal to them. This interplay, this constant dialogue between what was intended and what is perceived, is the fertile ground where art truly flourishes. It's a beautiful, sometimes messy, surrender of control that I've learned to embrace. I remember one early abstract piece where I was trying to convey a specific feeling of restless energy, but several viewers interpreted it as profound calm. Initially, I was frustrated, thinking I'd failed. But then, it dawned on me – their calm wasn't wrong, it was simply a different, equally valid resonance. That shift in perspective was a huge breakthrough for me as an artist, freeing me from the need to dictate meaning.

Ultimately, art isn't just about what the artist puts in, but also what the viewer brings to it. This co-creation of meaning is one of the most magical and personal aspects of aesthetic experience.

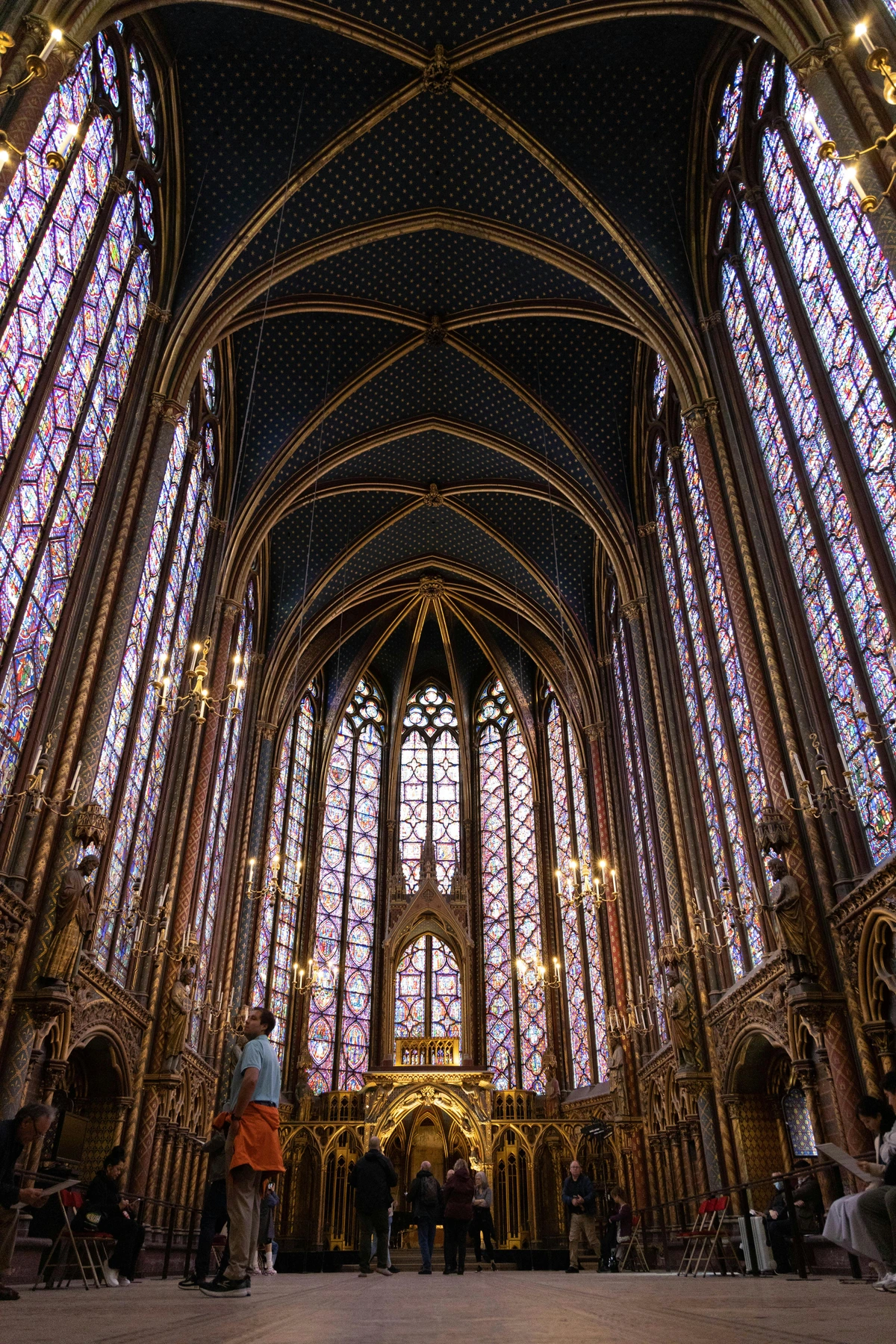

Beyond Beauty: The Sublime

But what about those moments when art doesn't just please us, but utterly overwhelms us, leaving us feeling small yet profoundly connected to something vast and powerful? Sometimes, art transcends mere beauty, pushing us into a realm of awe, wonder, or even a touch of terror – what philosophers call the Sublime. This isn't about prettiness, but about an overwhelming encounter that humbles us, makes us feel small yet profoundly connected to something vast and powerful. Think of the grandeur of a stormy sea, the dizzying complexity of a vast galaxy, or the overwhelming power of a Wagnerian opera.

The philosopher Edmund Burke, writing in the 18th century, explored the sublime as arising from feelings of terror, pain, and danger, but from a safe distance, which paradoxically can produce a species of delight. It's the thrill of confronting the immense, the uncontrollable, or the infinitely complex, that challenges our capacity to comprehend. In art, this could be the sheer scale of a monumental sculpture, the immersive experience of a Yayoi Kusama infinity room (check out our ultimate guide to Yayoi Kusama for more), or the unsettling yet captivating power of a Jean-Michel Basquiat piece that confronts you with raw, untamed energy (explore our ultimate guide to Jean-Michel Basquiat here). Romantic artists, in particular, often sought to evoke the sublime, depicting dramatic landscapes and powerful natural forces to stir deep emotional and spiritual responses. It's an aesthetic experience that engages us not just with pleasure, but with a sense of the immense, the boundless, the unfathomable, forcing us to confront the limits of our own understanding. Have you ever felt that profound, almost frightening pull towards something immense in art? Perhaps listening to Beethoven's Ninth Symphony, or gazing at Caspar David Friedrich's "Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog"? The sublime reminds us that art can offer more than just comfort; it can offer a profound confrontation with the limits of our perception and the vastness of existence.

The Multifaceted Purpose of Art

Beyond the quiet contemplation of beauty or the awe-inspiring experience of the sublime, why do we make art? And why do societies continue to value it? Art's role in human experience extends far beyond mere aesthetics; it serves a multifaceted purpose that can profoundly impact individuals and societies.

Personal Expression and Catharsis

For many artists, including myself, the act of creation is a deeply personal journey of expression and catharsis. It's a way to process emotions, articulate thoughts that defy words, and explore the internal landscape of the soul. My studio is often a sanctuary where feelings, both turbulent and serene, find form on the canvas. This intimate act of giving external form to internal states offers a powerful release, a way to make sense of the world and our place within it. It's the artist's personal narrative unfolding, not just for others, but for themselves.

Social Commentary and Critique

Art can function as social commentary, holding up a mirror to society's triumphs and injustices. From political cartoons to protest songs, from powerful installations addressing environmental concerns to poignant photography capturing human struggles, art provides a platform for dialogue, critique, and change. It can challenge norms, expose truths, and provoke thought in ways that other forms of communication cannot. Think of the Futurists, for example, who used art to celebrate technology and modernity, or, conversely, artists who critique societal ills through their work.

Exploration and Communication

It's also a powerful tool for exploration and communication. Artists often grapple with philosophical questions, scientific concepts, or personal narratives through their work. Abstract art, in particular, despite common misconceptions, is rarely "meaningless." It demands engagement, inviting us to explore form, color, and texture not as representations of external reality, but as expressions of an internal one.

Many assume abstract art is "easy" or "anyone could do it," but beneath the surface lies a rigorous understanding of composition, color theory, and an often intense emotional and intellectual process. It requires years of developing a unique artistic style and exploring layers and depth. My own abstract language is a testament to this, built on a dedication to communicating complex ideas and emotions that defy literal translation, forming a universal language that transcends cultural barriers.

Historical Record and Cultural Identity

Art also preserves history and cultural identity, acting as a visual record of civilizations, beliefs, and events. From ancient cave paintings to Renaissance frescoes, it offers insights into the past, connecting us to those who came before. In this way, art becomes a collective memory, enriching our understanding of humanity's long and winding story.

The Role of Art Criticism

Finally, art criticism plays a crucial role in shaping our aesthetic experience. Critics provide context, offer interpretations, and highlight formal qualities we might otherwise miss. While personal experience remains paramount, an informed critical perspective can deepen our appreciation and challenge our assumptions, guiding us through the vast and often perplexing world of art.

The Role of Personal Experience: Your Unique Lens

Having navigated the complex philosophical terrain of aesthetics and art's broader purposes, it's vital to remember that ultimately, art is experienced by individuals. Here's where it gets really interesting, and frankly, a bit messy in a wonderfully human way: our personal histories, our memories, even our current mood, all act as filters through which we perceive art. Have you ever gone through a tough time and found solace in a melancholic piece, or conversely, sought out vibrant, hopeful art to lift your spirits? I know I have.

I remember one particularly dreary winter in 's-Hertogenbosch, right around the time I was thinking of expanding my studio into a small museum space. Everything felt muted, almost suffocatingly grey. I gravitated towards bold, almost defiant color in my own work, a subconscious pushback against the drabness. When a visitor to my studio commented on the vibrancy, saying "It just feels... alive, especially today," it wasn't just a compliment; it was a confirmation that the art had connected with their own emotional state, providing a needed spark. It made me wonder about the hundreds of pieces I've seen in museums and galleries, and how my own life at that moment shaped my perception. Sometimes, a piece of art isn't just a canvas and paint; it's a mirror, reflecting what we bring to it. How has your own mood or personal history influenced your appreciation of a particular artwork? What about the environment in which you encountered it – did that play a role? If you're looking for art that resonates with your own inner world, perhaps my collection might hold a reflection for you.

Cultivating your aesthetic experience, then, becomes an active process. It means practicing active observation – looking closely, noticing details, forms, and textures. It means embracing personal biases while also challenging them, seeking out art that might initially feel uncomfortable but ultimately broadens your perspective. It's about developing emotional intelligence around your responses and allowing yourself to be vulnerable to art's power. It’s a journey of self-discovery, painted in hues you never expected.

The Enduring Mystery and Personal Connection

The philosophy of aesthetics, ultimately, isn't about finding a single, definitive answer to "what is beauty?" but about exploring the richness and complexity of our human experience with art. It's about understanding why certain shapes, colors, and forms trigger such profound responses within us, from the quiet hum of appreciation to the overwhelming roar of the sublime. It's about recognizing art's capacity to challenge, to comfort, to communicate, and to connect us across time and culture.

For me, the most beautiful thing about art is its capacity for endless discovery – both of the world and of ourselves. Every brushstroke I make, every piece you look at, is part of this ongoing, deeply personal dialogue. It's a journey, not a destination, and I'm endlessly fascinated by where it will take us next, always evolving, always revealing new facets of the human spirit. So, keep feeling, keep questioning, and let art continue to illuminate the beautiful, sometimes chaotic, often deeply personal landscape of your soul. What piece of art has moved you most profoundly, and why? Take a moment to reflect on your own aesthetic journey; it's a unique masterpiece in itself.