Roman Art's Enduring Legacy: From Empire to My Abstract Canvas

Explore Roman art's pragmatic realism, architectural genius, and narrative power. Uncover its profound, often surprising, influence on Western aesthetics, shaping everything from civic design to the very brushstrokes of my contemporary abstract paintings.

Roman Art's Enduring Legacy: Pragmatism, Realism, & My Abstract Canvas

You know, sometimes I'm elbow-deep in paint, trying to coax just the right chaos onto a canvas, and a strange thought hits me: how much of what I instinctively find pleasing, balanced, or even just right has its roots in some Roman artisan chipping away at marble two millennia ago? It's remarkable how those figures, with their togas and their legions, laid the visual groundwork for so much of what we consider beautiful, functional, and yes, even truly art. Far from being mere copycats of their Greek predecessors, Roman art forged its own distinct identity, driven by a pragmatism I deeply respect, a knack for grand-scale propaganda, and an almost brutal appreciation for the individual. This unique blend of purpose, realism, and ambition is precisely why its influence remains so pervasive, humming beneath everything from grand government buildings to, perhaps, even the abstract pieces you might find in my own art for sale collection.

It's the silent, ancient bassline to Western aesthetics, and in this article, we're going to crank up the volume. We'll explore this enduring, foundational impact through my artistic lens, delving into ancient innovations, their profound influence on today's artistic landscape, and how a conversation across millennia shapes not just history, but the very brushstrokes of my contemporary abstract work. Do you ever feel that pull from the past in your own creative endeavors?

The Roman Eye: From Greek Idealism to Veristic Realism – And Why That Matters

We often talk about Roman art 'borrowing' from the Greeks, and sure, they did. But let's be honest, who doesn't take a brilliant idea and run with it, polishing it to fit their own needs? The early Romans looked at, say, the idealized forms of a Praxiteles sculpture, all smooth lines and perfect proportions, and thought, "Hmm, beautiful, but where's the lived experience?" While Greek artists were busy chasing a kind of mythological perfection – all gods and goddesses looking flawlessly divine – the Romans were like, "Nah, let's show the wrinkles, the scars, the real story of a person's life and achievements."

Of course, while their gaze often turned south to Greece, Roman art wasn't formed in a vacuum. Earlier influences, particularly from the Etruscans, contributed significantly to their emphasis on realism and portraiture. The Etruscans, inhabiting much of central Italy before the rise of Rome, were masters of terracotta sculpture and vivid tomb painting, producing highly individualized funerary portraits, such as the famous L'Arringatore (or Aulus Metellus), a bronze statue from the late Etruscan period that perfectly captures individual features and a sense of civic duty, clearly prefiguring Roman verism. Their vibrant, narrative approach to art set a powerful precedent, also seen in their elaborate sarcophagi like the Sarcophagus of the Spouses, intricate bronze craftsmanship (like the Chimera of Arezzo), and monumental tomb frescoes that often depicted lively banquets and rituals. This early fusion of raw emotion and structured form, I often feel, laid the groundwork for my own blending of these elements in abstract art, seeking that primal, honest expression. Similarly, the dynamic drama and emotional intensity of Hellenistic art also filtered into their expressive sculptures and monumental works, adding layers of pathos and movement to their developing aesthetic, moving beyond the serene classicism of earlier Greek periods.

I find Roman portraiture utterly fascinating, actually. It’s that unvarnished honesty. Where a Greek sculptor might have polished away every imperfection, a Roman artist was capturing the CEO, the senator, the soldier, with every single distinguishing feature – the hook nose, the furrowed brow, the tell-tale scar. This wasn't vanity; it was verism, a hyper-realism that valued character, achievement, and lineage over some abstract notion of beauty. The Romans emphasized these individual traits because they were a practical, status-conscious society that valued civic duty and the tangible accomplishments of its leaders and prominent citizens. This fearless authenticity in their portrayal of lived reality laid a profound cornerstone for how we view the human experience in art: not as an ideal, but as a lived reality. This profound emphasis on individuality and narrative detail, I often feel, subtly influences my own abstract work, where I find myself striving to capture that same raw authenticity, that lived reality, even in my abstract pieces, where the 'wrinkles' might be textural variations or unexpected color juxtapositions. How do you see authenticity reflected in different art forms?

Roman Innovations: Beyond the Pedestal – The Practical Genius of an Empire

So, they mastered the individual portrait, capturing faces with startling honesty. But the Romans didn't stop there. They were, if nothing else, ambitious. Their genius, I think, truly soared when it came to engineering and materials. This wasn't just about making pretty things; it was about making things that worked, on a massive scale, for a massive empire. And that, in itself, is an aesthetic statement – a kind of powerful, pragmatic beauty that resonates even today. In my own work, I often wrestle with the practicalities of creation – the right medium, the durable surface – and I can't help but feel a kinship with that Roman drive for functional excellence, a desire to create something both conceptually rich and physically enduring. It's like finding the perfect formula for a new paint medium; that blend of science and art is truly Roman.

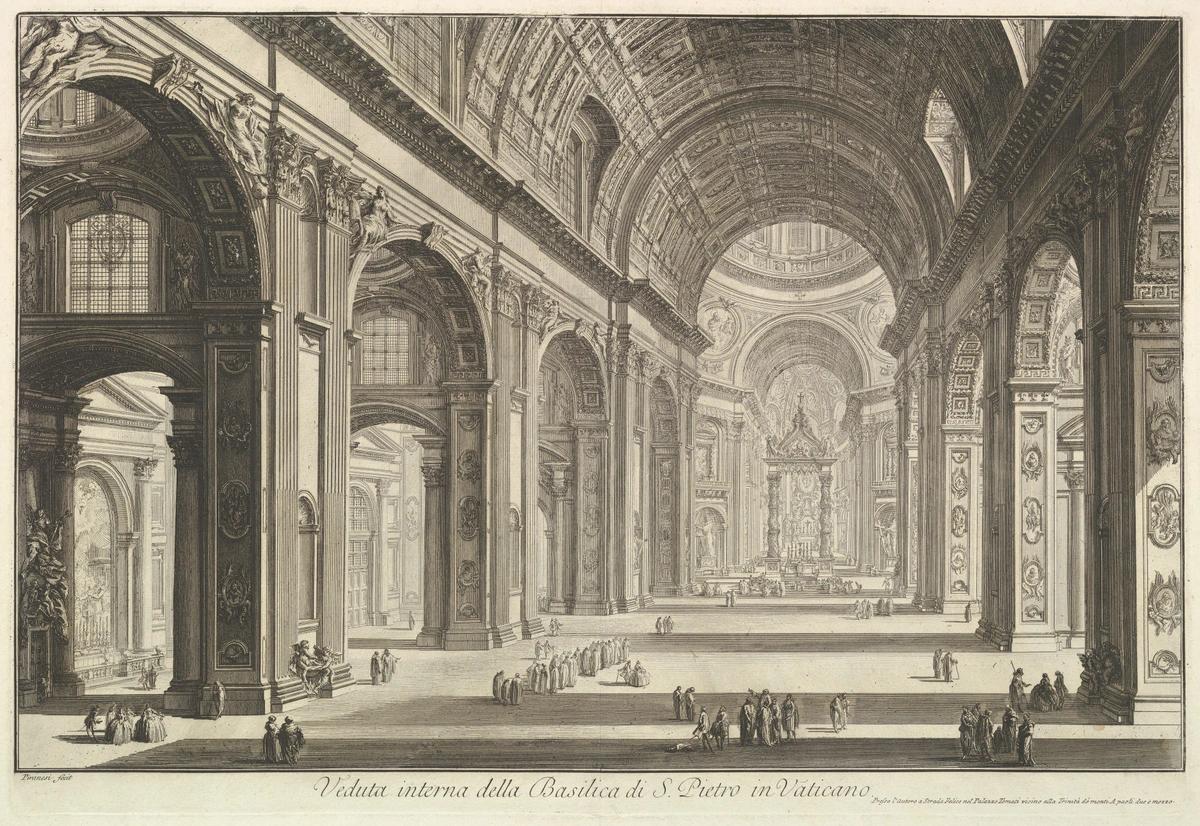

Architectural Grandeur: Concrete, Curves, and Civic Life

These Romans, they weren't about subtlety. Their idea of a public bathhouse was probably grander than some modern museums I've visited. Their innovation with concrete, for example, was an absolute game-changer – a true "aha!" moment in history that allowed them to build structures of unprecedented scale and durability. Think of the awe-inspiring curve of the Colosseum, the perfect dome of the Pantheon (still standing, mind you!), or the intricate network of aqueducts. These weren't just buildings; they were statements of power, engineering prowess, and communal living. I often find myself sketching forms that echo the monumental yet balanced nature of these ancient structures, even when the final piece is entirely abstract.

The very concept of grid-patterned cities, robust sanitation systems, and extensive road networks connecting an empire – these were Roman inventions, shaping how we live in cities even today. Their architectural vocabulary, with its emphasis on symmetry, proportion, and monumental scale, laid a significant foundation for Western architecture that echoed for centuries. When I see a classical facade in, say, 's-Hertogenbosch near my museum, I can't help but see those Roman echoes. Even the layout of our modern city squares and grand public fountains often echo these ancient Roman principles of ordered public space. Consider also the basilica – originally a Roman public building used for law, commerce, and assembly – whose form directly inspired the early Christian churches and subsequent civic architecture, becoming a blueprint for places of justice and community. Beyond their sheer scale, the Romans perfected structural elements like the arch, vault, and dome, allowing them to enclose vast spaces and create complex, multi-level structures previously unimaginable. This mastery of engineering and urban planning, extending to military fortifications and bridges like the Pont du Gard, created a coherent, functional, and visually imposing empire. It's a testament to applying a rational, problem-solving approach to aesthetics, something I aim for in my own compositions – a balance between wild creativity and thoughtful execution.

Narrative Reliefs: The Ancient PR Campaign

If the Greeks loved their myths, the Romans loved their victories. And they weren't shy about broadcasting them. Think of the narrative reliefs found on triumphal arches, like the Arch of Titus, or, most famously, on Trajan's Column. This wasn't just decorative; it was the ancient "look at me, I'm awesome" campaign, an incredibly sophisticated form of public relations. Trajan's Column, for instance, literally spirals upwards with a continuous, documentary-style depiction of his Dacian Wars. It's a meticulously carved historical record, designed not just to recount events but to glorify the emperor, to justify conquests, and to inspire awe (and maybe a little fear) in the populace. Crucially, these reliefs often strived for historical accuracy, or at least a convincing portrayal of it, distinguishing them from purely mythological narratives and amplifying their propaganda value. Other significant examples include the Column of Marcus Aurelius, which narrates his military campaigns with similar continuous narrative, and the richly adorned Ara Pacis Augustae, depicting Augustus's peaceful reign through processional and allegorical scenes. It's the original Instagram influencer, but with significantly more marble and less avocado toast. This narrative, almost journalistic approach to visual history profoundly influenced everything from medieval tapestries to modern historical painting and public monuments. They were masters of telling their story, a lesson many governments and brands have since taken to heart. It makes me wonder, what narratives are we trying to tell with our art today, and for whom?

Art for the Empire and the Everyday: The Role of Patronage and Workshops

Moving beyond grand public works and imperial propaganda, patronage played a crucial role in shaping Roman art at all levels of society, reflecting the empire's social fluidity. Imperial commissions glorified emperors and their achievements, while senatorial families commissioned portraits and monuments to assert their lineage and power. But it wasn't just the elite. Private citizens, from wealthy merchants to freedmen (former slaves who achieved financial success), also commissioned art for their homes, tombs, and businesses. This widespread patronage demonstrated social status and personal taste, and was often displayed through elaborate wall paintings (like those in the House of the Vettii in Pompeii, showcasing the Four Pompeian Styles), floor mosaics, or detailed tomb reliefs depicting their trades and lives, such as the baker Eurysaces' tomb in Rome, or the bustling market scenes found in Ostia Antica. This dynamic revealed the increasing social mobility within Roman society, where art became a highly visible means for individuals of various backgrounds to assert their identity and accomplishments. This broad reach was facilitated by organized workshops and proto-guilds of artisans and sculptors, who fulfilled commissions efficiently, fueling the creation of powerful public narratives and intimate domestic art alike. It reminds me how deeply art can be interwoven with social standing and personal storytelling, even now – perhaps especially now, in the age of personal branding. What drives your choices in art, if not to tell a story or make a statement?

The Roman Palette: Sculpting, Painting, and Decorating an Empire

Beyond the grand statements of architecture, propaganda, and public life, Roman artists were busy innovating in more intimate, yet equally impactful, ways, often drawing on a wider range of materials than just the marble and bronze we typically associate with them. The shift from monumental to more personal expressions of art reflects the Romans' comprehensive approach to visual culture, aiming to enrich every aspect of life.

Sculpture: From Verism to Monumental Commemoration

As I mentioned earlier, Roman sculpture took Greek traditions and, well, gave them a very Roman makeover. While we've talked about those wonderfully honest portraiture, Roman sculptors also created monumental public works – massive bronze emperors on horseback, victorious generals, or allegorical figures, statements of power and lasting memorials. Beyond these, their output included elaborate sarcophagi adorned with intricate narrative scenes, depicting mythological events, biographical moments, or even battle scenes. These served as a more accessible form of historical or biographical art than grand columns, and decorative reliefs graced altars, temples, and private homes. And a crucial point: though many museum pieces appear pristine white today, Roman sculptures were originally vibrantly painted with bold reds (cinnabar), blues (Egyptian blue), golds, and greens, along with purples and yellows. The fading of these pigments over millennia has given us a false impression of their original polychromatic splendor. This shift from idealized forms to this more narrative and commemorative function is, to my mind, a hallmark of Roman sculptural output, inspiring countless equestrian statues and memorial sculptures in later eras. It's about remembering, celebrating, and sometimes, just letting everyone know who's boss – and honestly, who doesn't want their work to be remembered and celebrated long after they're gone?

Wall Paintings and Mosaics: A Window into Roman Life and Style

When I look at the vibrant wall paintings unearthed from Pompeii and Herculaneum, I'm always struck by their sheer sophistication. These weren't just slapped on walls; they reveal a deep understanding of perspective, clever trompe l'oeil (literally "fool the eye") effects, and a surprisingly modern use of color. Roman painters mastered fresco techniques, developing styles like the famous Four Pompeian Styles, each with a distinct purpose in transforming domestic spaces:

- First Style (Incrustation Style): Aimed to impress through perceived expense, imitating colorful marble slabs with painted stucco to mimic grand architectural elements.

- Second Style (Architectural Style): Created illusionistic architectural vistas and landscapes to virtually extend the room and open up walls to fantastical scenes, often with mythological narratives, making rooms feel larger and more opulent.

- Third Style (Ornate Style): Emphasized elegance and delicacy with small, central mythological scenes or vignettes set against monochrome backgrounds, featuring slender, almost abstract, architectural elements, offering a more refined and intimate ambiance.

- Fourth Style (Intricate Style): A complex, eclectic mix of all previous styles with fantastical architectural elements, crowded compositions, and often incorporating large-scale mythological narratives and dramatic theatricality – a style that would later influence Baroque illusionism, pushing architectural illusion to its limits and creating a sense of grand spectacle.

What was their purpose? Beyond sheer aesthetics, they were status symbols, visual narratives, and a way to bring the outside world, or idealized worlds, indoors. This ability to transform spaces through two-dimensional art was matched by their skill in creating durable and intricate mosaics. Made from countless tiny stone, glass, or even enamel tesserae (individual pieces), these mosaics adorned floors and walls. Using techniques like opus tessellatum (larger tesserae for broader, bolder patterns and durability) and opus vermiculatum (smaller, finer tesserae for detailed pictorial scenes, often forming central emblems, literally 'worm work' due due to the winding lines of the tesserae), they created durable and elaborate pictorial narratives or geometric patterns that still dazzle today. They were art that could withstand centuries of foot traffic – now that's functional design. The Romans truly understood how to use color to transform spaces. Their love for spectacle extended to theater and stage design, where elaborate backdrops and props created immersive visual experiences, further showcasing their narrative flair and an early form of immersive art.

Decorative Arts: Beauty in the Everyday and Beyond

From finely crafted pottery and intricate metalwork to exquisite jewelry and advanced glassware, Roman decorative arts truly demonstrated a blend of functionality and refined aesthetics. Their advanced glassmaking techniques, for example, produced stunning blown glass vessels, delicate cameo glass (carved opaque glass over a contrasting colored layer, like the famous Portland Vase), intricate mosaic glass, and even elaborate cage cups (diatreta) – intricate vessels with an outer cage carved away from an inner cup, showcasing both luxury and unparalleled technical prowess. Examples like terra sigillata pottery, characterized by its glossy red surface and molded relief decoration, were widely popular across the empire. Intricately patterned silverware, bronze oil lamps, and even weaponry often adorned with mythological figures or everyday scenes, also provided beauty in the everyday. While extensive textile arts are scarce due to degradation, we know from written accounts and preserved fragments that richly dyed and woven fabrics were important status symbols and decorations for homes and clothing. Even in early manuscript illumination, rudimentary artistic elements like decorated initials and simple illustrations began to appear, laying groundwork for future artistic expression. And let's not forget Roman cartography; their practical approach to understanding and organizing their vast empire through detailed mapmaking (like the Tabula Peutingeriana) was, in its own way, an aesthetic act of control and vision. These smaller-scale works often incorporated motifs and stylistic elements that would reappear time and again in later periods, testifying to the enduring appeal and quality of Roman design and their role as markers of social status. It reminds me that good design, whether grand or humble, truly lasts – a lesson I always try to apply, even when I'm just trying to pick the right frame for a painting.

The Enduring Echoes: Roman Art in Western Aesthetics – Still Shaping Our World

The fall of the Western Roman Empire might sound like the end of an era, but for Roman art, it was more like going underground before a grand revival. Its legacy didn't vanish; it simply transformed into a persistent undercurrent, occasionally bubbling up with renewed vigor, shaping our aesthetic sensibilities in ways we might not even consciously realize. I often wonder how much of my own approach to strong, structured composition, even in abstract art, owes a subtle nod to this enduring Roman spirit. While the Greeks often elevated the concept of the individual artist, the Romans were master craftsmen whose collective impact created an artistic language that still speaks volumes.

The Renaissance (11th-17th Century): A Grand Revival

The Renaissance wasn't just a 'rebirth' of art; it was a full-blown Roman fan club. Artists like Michelangelo, Raphael, and Leonardo da Vinci didn't just admire Roman sculpture and architecture; they studied them, meticulously. They dug up ruins, read ancient texts (like Vitruvius' De architectura for architectural principles, and Pliny the Elder's Natural History for details on ancient artists and their techniques, even recipes for pigments), and basically became art historians before it was cool. Think of the profound impact of the discovery of the Laocoön Group on Michelangelo, or how architects drew inspiration from the perfect dome of the Pantheon and the narrative grandeur of the Arch of Titus. The Renaissance emphasis on humanism, anatomical accuracy, perspective, and classical motifs directly revived Roman artistic principles. Those grand, balanced composition you see in High Renaissance works, the celebration of the human form – they’re direct descendants of Roman influence. It’s almost like they decided, "Right, let's pick up where those Romans left off, but with a bit more… drama, and perhaps a touch more technical wizardry."

Neoclassicism (18th-19th Century): Order, Reason, and Togas (Metaphorically)

Centuries later, when people got a bit tired of the frills and fancies of Baroque and Rococo, they explicitly looked back to ancient Rome (and Greece) for a dose of noble simplicity and austere grandeur. The Neoclassical movement, with artists like Jacques-Louis David (whose "Oath of the Horatii" perfectly embodies Roman stoicism and civic virtue) and sculptors like Antonio Canova, consciously emulated Roman subject matter, rationality, and public morality. You see it everywhere – from government buildings like the US Capitol and public monuments across Europe and America to the very notion of civic virtues embodied in art. Consider the Brandenburg Gate in Berlin, the Panthéon in Paris, or the British Museum, all direct homages to Roman temple architecture, showcasing a return to classical rigor. It’s like they were saying, "Let's bring back some gravitas, some seriousness. Fewer cherubs, more columns!" And honestly, sometimes my own abstract work feels like a reaction to too much 'noise,' a desire to return to a fundamental order, a Roman echo.

Beyond Aesthetics: Roman Symbols, Law, and the Fabric of Our Cities

But the Roman spirit didn't just show up in grand, overt revivals; its influence is far more subtle and pervasive, weaving its way into the fabric of our visual world and even our civic structures. The very concept of a public museum, the monumental scale of civic architecture, the use of linear perspective in painting, and the idea that art can tell a continuous narrative – all owe a profound debt to Roman precedent. Roman aesthetics seeped into the very symbols of authority and law that persist today. Think of the fasces, bundles of rods with an axe, symbolizing magisterial power and unity, often seen in governmental emblems from the French Revolution to the US House of Representatives. Or the eagle, a powerful Roman legionary standard representing military might and imperial reach, still used as a national symbol by many nations. These visual cues, laden with Roman meaning, remind us how deeply their aesthetic and political language became intertwined and enduring.

Moreover, as I mentioned, the Roman basilica laid the architectural groundwork for countless civic buildings and places of justice, influencing the very design of our public spaces and the architectural language of order that governs them. Beyond the visual, Roman legal and philosophical traditions (like Stoicism, emphasizing duty, virtue, and rational order) also indirectly influenced artistic themes, echoing in the purposeful nature of much Roman art, which often aimed to instruct or inspire civic virtue. Even Roman satire, found in mosaics, caricatures, and domestic scenes (such as the explicit and often humorous frescoes in Pompeian brothels), offers a glimpse into their pragmatic and often critical view of society, resonating with contemporary artistic commentary. It’s almost as if they set up the default settings for Western civilization – the very operating system, if you will – and we've been customizing them ever since. And for an artist, understanding this historical journey is invaluable, almost like looking back through my own timeline to understand my influences and the universal questions that art always seems to ask. It's a humbling thought, how much we still build upon these ancient foundations.

So, what began as practical solutions for an expanding empire, a penchant for honest portraiture, and a desire to project power, has left an indelible mark on everything we see. From the grandest cathedral to the quietest gallery, from the straight lines of our streets to the philosophical underpinnings of our justice systems, the echoes of Roman art are all around us. It's a humbling and inspiring thought, how much we owe to those who came before, building and creating with such enduring vision, shaping not just what we see, but how we understand our world and, perhaps, even how we dare to create – much like how I strive to create enduring, meaningful work myself, sometimes wrestling with chaos, sometimes imposing order, much like those ancient Romans. If you're inspired to explore how these ancient principles resonate in contemporary abstraction, I invite you to browse my collection of art for sale.

Your Roman Art FAQs – Answered (My Way)

Q: So, what's really the big difference between Greek and Roman art?

A: Ah, the classic question, and one I think about often! For me, it boils down to focus and philosophy. While the Greeks often aimed for an idealized, almost unattainable beauty – think perfect gods and goddesses, a kind of serene, abstract perfection – the Romans were all about the here and now, the practical reality. They wanted to capture the real person, with all their quirks and wrinkles (hello, verism!), and tell their actual, often military or civic, stories through historical reliefs. Plus, they were total engineering nerds, which led to mind-blowing architectural innovations with concrete, arches, vaults, and domes that the Greeks just didn't push as far. It’s like one wanted to show you the ideal dream of humanity, and the other wanted to show you the incredibly effective, pragmatic, and civically-minded reality of empire. Simple, right?

Q: Did Roman art use color, or was it all just white marble?

A: Such a good question, and a common misconception! I mean, when we see Roman statues in museums, they're usually pristine white, right? But believe me, those ancient Romans loved color! Their sculptures and architectural elements were originally vibrantly painted – think bold reds (like cinnabar), blues (like Egyptian blue), and golds, along with rich purples and greens. Most of those pigments have faded over two millennia, sadly, leaving us with the stark white marble we associate with antiquity today. However, if you look at their stunning wall paintings and intricate mosaics (especially from places like Pompeii and Herculaneum), you get a vivid, colorful peek into their polychromatic world. They weren't afraid to go bold; if anything, our modern eyes are just catching up to the vibrant reality of Roman art! It makes you rethink history, doesn't it?

Q: How did Roman art spark the Renaissance?

A: "Spark" is a great word for it! The Renaissance artists basically dug up Roman art, blew off the dust, and said, "Yes! This is what we've been missing!" They studied Roman ruins, sculptures, and old texts like treasure maps (Vitruvius and Pliny the Elder being crucial guides). This brought back a focus on humanism (celebrating individual achievement and dignity, much like Roman portraiture did), realistic anatomy, perspective, and those grand, classical composition. It was less about just seeing Roman art and more about re-engaging with its entire philosophy – celebrating humanity, scale, order, and a sense of tangible reality. It was a proper comeback story for classical ideals, a profound intergenerational conversation, and honestly, a testament to how some ideas just last.

Q: What was the main purpose of Roman art, beyond just looking good?

A: Oh, it was rarely just about looking good, though it certainly did! Roman art was profoundly utilitarian, a tool to achieve specific goals for a practical, expansionist society. Its main purposes were multifaceted: propaganda (glorifying emperors, justifying conquests, asserting power through monumental arches and columns), civic identity (fostering a sense of shared Roman values and history among citizens, often through public works), personal commemoration (honoring ancestors, celebrating the achievements of individuals through veristic portraits and funerary monuments), and even religious practice (adornment of temples, depictions of gods for worship in public and private spheres). And for everyday citizens, it was also about status and personal expression within their homes and tombs, a way to show off their success. It was art with a job, reflecting their worldview of order, duty, and tangible success. It’s a bit like my own art; it might look abstract, but deep down, it's always trying to do something, to convey a feeling or a truth that resonates.

Q: Is Roman art still a "thing" today? Like, beyond old buildings?

A: Oh, absolutely! And this is where it gets really interesting for me as an artist. Roman art's influence isn't just in the obvious stuff like government buildings or big public statues. It’s in the underlying aesthetic principles – the order, the proportion, the sheer functionality that we often take for granted in modern design. Think of the clean lines in minimalist furniture, the structured layouts of modern websites, or even the grand, aspirational branding of major corporations. Their emphasis on narrative and realism? Still resonates, pushing us to tell our own stories, wrinkles and all, whether through social media or documentary film. Even contemporary architectural styles like Beaux-Arts or certain forms of Brutalism, with their monumental scale and use of concrete, directly echo Roman principles. Every time I try to balance chaos and structure in a painting, I'm tapping into something that, consciously or not, was honed to perfection by the Romans. It’s everywhere if you just know how to look. Where do you see it popping up in your daily life, in the quiet corners of your city or home?