Pop Art Unveiled: My Journey Through a Playful Cultural Revolution

I still remember standing in front of a particularly stoic Renaissance portrait once, feeling utterly lost. The sheer weight of history, the intense gazes, the unspoken expectations – it was like being caught in a serious academic debate when all you wanted was a good story. I often thought, "Is this what art has to be? So profound it keeps me at arm's length?" Then, like a splash of vibrant color across a monochrome canvas, Pop Art entered the scene. It was a cheeky, vibrant disruption. Suddenly, art was less about hushed reverence and more about a joyful, sometimes mischievous, conversation. This wasn't just a stylistic shift; it was a genuine cultural revolution that didn't just transform what happened within galleries but fundamentally reshaped how we perceive the everyday. In this journey, we'll delve into its audacious roots, meet the artists who dared to defy convention, explore its lasting impact, and understand why it continues to resonate so deeply with my own creative path.

My First Encounter: A Familiar Face in a Posh Gallery

I vividly remember stumbling upon a reproduction of Andy Warhol's iconic soup cans. My initial thought? "Wait, is that allowed?" It was so mundane, so everyday, yet it was right there, demanding attention. It wasn't a soaring landscape or a tortured self-portrait; it was a soup can. It was a moment that didn't just make me smile; it cracked open my entire perception of art, showing me it didn't have to be this elusive, high-brow thing. It could be right there, in your grocery cart, staring back at you with a sly wink. And it certainly was allowed. That feeling of sudden recognition, that immediate connection, was like a jolt – a realization that art could speak my language, the language of the tangible, the familiar.

This immediate connection, this sense of recognition, is what I think drew me (and so many others) to Pop Art in the first place. This initial jolt of recognition with Warhol's soup cans was just the beginning of understanding how Pop Art fundamentally shifted the art world's gaze. It was a refreshing splash of cold water after the intense emotional depths of Abstract Expressionism. While incredibly powerful, Abstract Expressionism often felt like a private conversation I wasn't privy to, a beautiful yet intense journey I sometimes struggled to join, all about the artist's inner turmoil expressed through spontaneous marks. Suddenly, art was talking to me, about my world, in a language I recognized. It helped bridge that gap between the art I felt I should appreciate and the art I instinctively did. This personal resonance with the accessible and familiar was, I later realized, a direct echo of the broader cultural shift Pop Art instigated – a bold rebellion against the art world's ivory tower.

The British Genesis: Intellectual Groundwork

Across the Atlantic, a vibrant scene was already brewing. Emerging in the mid-1950s, the Independent Group in Britain found itself grappling with a post-WWII landscape marked by austerity and rebuilding. Yet, amidst the rationing and traditional society, they witnessed a compelling influx of vibrant American consumer culture – Hollywood films, glossy magazines, and packaged goods. This stark contrast, a world of aspiration clashing with their own realities, fueled their critical examination and celebration of American mass culture. Figures like Richard Hamilton, Eduardo Paolozzi, and art critic Lawrence Alloway (who coined the term "Pop Art" in 1956) were central to this intellectual groundwork. Hamilton's seminal 1956 collage, "Just what is it that makes today's homes so different, so appealing?", is considered a foundational work. It’s a masterclass in assembling consumerist imagery – a bodybuilder, a pin-up, a vacuum cleaner – into a witty, critical, and surprisingly prophetic commentary on modern aspirations. Paolozzi's earlier collages, such as his 1947 "I was a Rich Man's Plaything," also predated the American movement, showcasing a fascination with American advertisements and technology. Their work laid the intellectual groundwork for the American movement, proving that the everyday was indeed ripe for artistic exploration and setting the stage for a grander rebellion.

Proto-Pop Preamble: Dismantling Artistic Boundaries

The intellectual groundwork laid by the British group was soon amplified by artists across the Atlantic who pushed artistic boundaries in their own unique ways. Before Pop Art fully blossomed with its bold, direct embrace of consumer imagery, Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns were quietly dismantling traditional artistic boundaries, effectively opening the door for what was to come. Often considered precursors, their revolutionary approach centered on dismantling the idea of the heroic, individual artist's touch and the strict divisions between art forms. Crucially, their work directly countered the prevailing ethos of Abstract Expressionism, which emphasized the artist's subjective experience and the formal purity of abstract forms. Instead, Rauschenberg and Johns brought the mundane into the sacred, using techniques that echoed commercial reproduction and incorporating everyday objects not just as subjects, but as integral components of their art. They were often labeled Neo-Dadaists for their similar anti-art sentiments and use of found objects, creating a vital bridge between the artistic provocations of the early 20th century and the commercial imagery that would define Pop Art.

Rauschenberg's 'combines' blended painting and sculpture with found objects – from tires to soda bottles, street signs, and fabric scraps – blurring the lines between art, everyday detritus, and personal experience. His innovative use of familiar, often discarded, elements from daily life directly prefigured Pop Art's subject matter. Johns, with his iconic paintings of flags and targets, took universally recognizable symbols and stripped them of their usual meaning, forcing us to simply see them as painted surfaces – focusing on the texture, color, and form of the paint itself rather than patriotic or military connotations. Both artists integrated popular culture elements and commercial techniques, pushing the boundaries of what art could be and paving the way for the bolder, more direct statements of Warhol and Lichtenstein. They showed that an image didn't have to be 'original' to be profound, and that the mundane could hold immense artistic power. Their work was instrumental in demonstrating that the artistic "hand" could be detached, and that imagery from the everyday could be elevated, directly influencing Pop Art's detached aesthetic and its embrace of appropriation.

Pop Art's Bold Rebellion: Challenging the Ivory Tower

Imagine a world saturated with the optimism and anxieties of post-war consumerism: the booming economy, the rise of television beaming advertisements into every home, a burgeoning youth culture, and the pervasive influence of mass media. Yet, art largely remained in the realm of deep introspection, focused on subjective experience and formal purity. "Why should art be so incredibly serious?" I can almost hear a frustrated artist asking, tired of the intense emotional depths and perceived elitism. Pop Art burst forth, a glorious, irreverent rebellion. Emerging in the mid-1950s in Britain and truly flourishing in the late 1950s and 1960s in America, it felt like artists were collectively exhaling, a sigh of relief from the intense introspection of previous movements like Jackson Pollock's drip paintings or Mark Rothko's color fields. While those movements explored profound inner worlds – often through the "tortured genius" lens – Pop Art looked outwards, declaring, "Hey, that's our reality. Why isn't that art?" It was as if artists were ripping off artistic blindfolds, letting go of the adherence to traditional subject matter and formalist concerns, and instead, looking squarely at the booming post-war consumer culture.

It wasn't the first time artists challenged the establishment. One could trace this rebellious spirit back to the provocations of Dadaism, with its anti-art gestures and embrace of nonsense, directly questioning the very definition of art. And the dreamscapes of Surrealism, which challenged reality through the irrational and subconscious, offered a blueprint for incorporating unexpected, everyday elements. But Pop Art brought this challenge into the vibrant, commercialized realm of everyday consumer culture. It embraced advertisements, comic books, product packaging, and celebrity worship. Mass media wasn't just what they painted; it was how they painted. The bold, graphic simplicity, the vivid colors, the reproducibility – these were direct influences from the very advertising and print media they depicted. They didn't just depict these elements; they elevated them, often with a detached, mechanical precision that mirrored commercial production techniques, deliberately de-emphasizing the artist's unique hand and ego. This practice, known as appropriation, was central to Pop Art, taking existing images and recontextualizing them, profoundly questioning notions of originality and authorship in a world increasingly flooded with reproduced imagery.

Using commercial methods like silkscreening, Benday dots (small, uniform dots used in printing to create tonal or color effects), bold colors, and graphic lines, Pop Art became a playful, ironic, and sometimes critical commentary on modern life. It defiantly blurred the lines between "high art" – the traditional, revered forms typically found in museums – and "low culture" – the everyday, mass-produced images we encountered in magazines, on billboards, and in grocery stores. This daring move absolutely infuriated some purists. I can almost hear the furious spluttering of one imaginary critic: "This is a 'dumbing down' of art! A betrayal of its sacred, elevated purpose! My dear chap, where is the soul?!" And honestly, I find that amusing. This reaction stemmed from a belief that art should transcend the mundane, that its value lay in its rarity, its profound conceptual depth, or the visible hand of a master. Pop Art, with its mass-produced imagery and commercial techniques, seemed to scoff at all of that, presenting itself not as a gateway to the sublime, but as a mirror reflecting the very commercialism some felt art should critique. While Pop Art was indeed criticized by some for being superficial, for merely celebrating consumerism rather than truly critiquing it, and for potentially commodifying art itself, its accessible nature also democratized art. It encouraged viewers to critically engage with the overwhelming imagery of their daily lives, turning the act of seeing into an act of questioning. It proved that art could be popular, understood by everyone, not just a select few, becoming a significant cultural revolution that both reflected and shaped the collective consciousness. Its commercial viability also transformed the gallery system itself, ushering in an era where art's market value became increasingly intertwined with its popular appeal, a shift that continues to ripple through today's art world.

Key Characteristics of Pop Art | Influential Artists (Examples) |

|---|---|

| Everyday Objects as Subject | Andy Warhol, Claes Oldenburg |

| Mass Media Imagery | Roy Lichtenstein, James Rosenquist |

| Bold, Graphic Style | Richard Hamilton, Robert Indiana |

| Commercial Techniques | Andy Warhol (silkscreening) |

| Irony & Parody | Roy Lichtenstein (Benday dots) |

| Blurring High/Low Art | Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg |

The Superstars of the Everyday: Icons of a New Era

Building upon the intellectual foundations and proto-Pop experiments, the movement truly took hold through the captivating works of several iconic artists who became synonymous with the Pop Art explosion:

- Andy Warhol: His exploration began with those iconic soup cans, but quickly expanded to include celebrity portraits like the famous Marilyn Diptych, and commercial products. He masterfully employed silkscreening to mass-produce images, mirroring the mass production of consumer goods and celebrity personas. This detached, mechanical precision was not just a technique; it was a statement that deliberately de-emphasized the artist's unique hand and challenged notions of artistic originality in a consumer-driven age. Warhol's legendary studio, The Factory, became a hub of avant-garde activity, further blurring the lines between art, commerce, and celebrity culture. His work questioned originality, fame, and the very nature of art in a consumer-driven society – a surprisingly deep commentary delivered with a cool, detached gaze.

- Roy Lichtenstein: His large-scale comic book panels, complete with his signature Benday dots and dramatic speech bubbles, were a revelation. He took something ephemeral and often dismissed, like a single frame from a comic, and blew it up, forcing us to consider its composition, its narrative, and its sheer visual power. The speech bubbles were crucial, not just conveying narrative or emotion, but sometimes creating a sense of detachment from the depicted drama, inviting viewers to analyze the artificiality of media. His 'Whaam!' is probably the most iconic, but I love how he captures a fleeting moment of drama or emotion with such graphic precision, as seen in his famous 'Drowning Girl'. Personally, his work always makes me smile – it's art that doesn't take itself too seriously, which I deeply appreciate because sometimes art should just be fun and visually arresting, not just profoundly conceptual.

- Claes Oldenburg: Taking everyday objects and rendering them in colossal, often soft sculptures made from materials like canvas, vinyl, or plaster. A giant clothespeg? A squishy toilet (like his famous 'Soft Toilet')? Or perhaps a colossal 'Floor Burger' that looks almost edible? It's absurd, playful, and brilliant. His influential 'The Store' project (1961) transformed a rented storefront into an art installation, selling plaster sculptures of everyday consumer items, further blurring the lines between art and commerce, and making a powerful statement about the abundance of American goods. By radically altering scale, material, and context, Oldenburg challenged our perception of these mundane things, forcing us to re-evaluate their function, their materiality, and their very existence. It’s the kind of art that makes you laugh, then makes you think: why is that so funny? And what does it say about our relationship with these mundane things? Oldenburg’s work is a masterclass in making the ordinary extraordinary, transforming the overlooked into monumental statements.

- James Rosenquist: Known for his large-scale, billboard-like paintings that often combine disparate commercial images – a car fender next to a woman's face next to a plate of spaghetti – creating a fragmented yet cohesive commentary on American consumer culture. His work, like "F-111," draws directly from advertising aesthetics and scale, utilizing monumental canvases to bombard the viewer with a cacophony of consumer imagery. This immersive scale forced a confrontation with the relentless flow of media in daily life, compelling us to piece together a narrative from a visual explosion that mirrored the experience of advertising itself.

- Other Noteworthy Voices: While Warhol, Lichtenstein, and Oldenburg often dominate the narrative, artists like Robert Indiana (famous for his iconic "LOVE" sculpture and graphic word-based art) also contributed significantly, extending Pop Art's reach into typography and public installations.

The Lasting Echo: Pop Art's Undeniable Influence and Cultural Legacy

These iconic artists didn't just create art; they ignited a movement that would forever change the landscape of creative expression. Pop Art wasn't just a fleeting trend; it fundamentally altered the trajectory of art by opening the floodgates for artists to draw inspiration from anywhere. Suddenly, advertising, cartoons, and mass media were valid sources, providing a rich, accessible language for commentary and creativity. This paved the way for future movements like Neo-Expressionism, street art, and conceptual art, extending its reach far beyond the canvas.

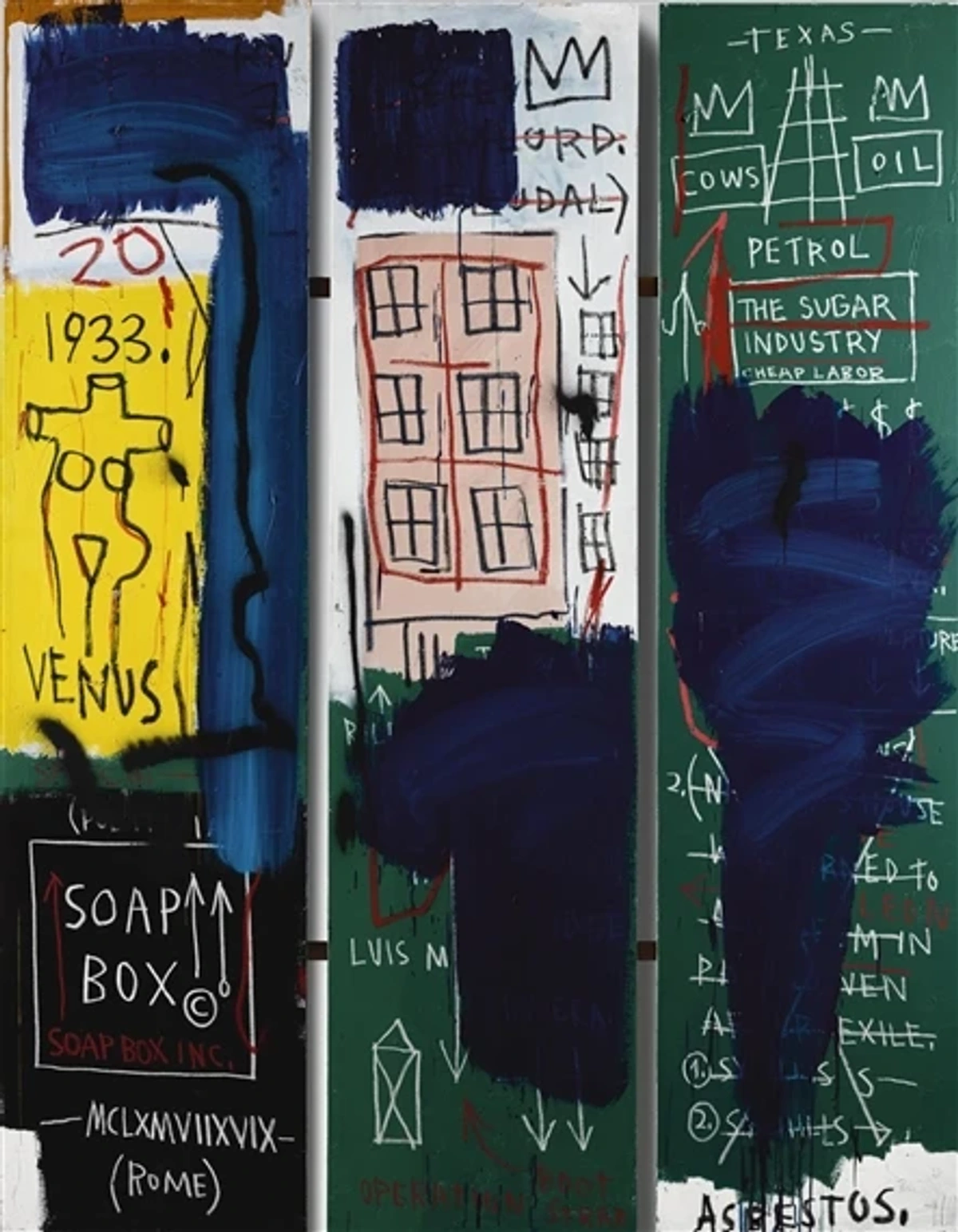

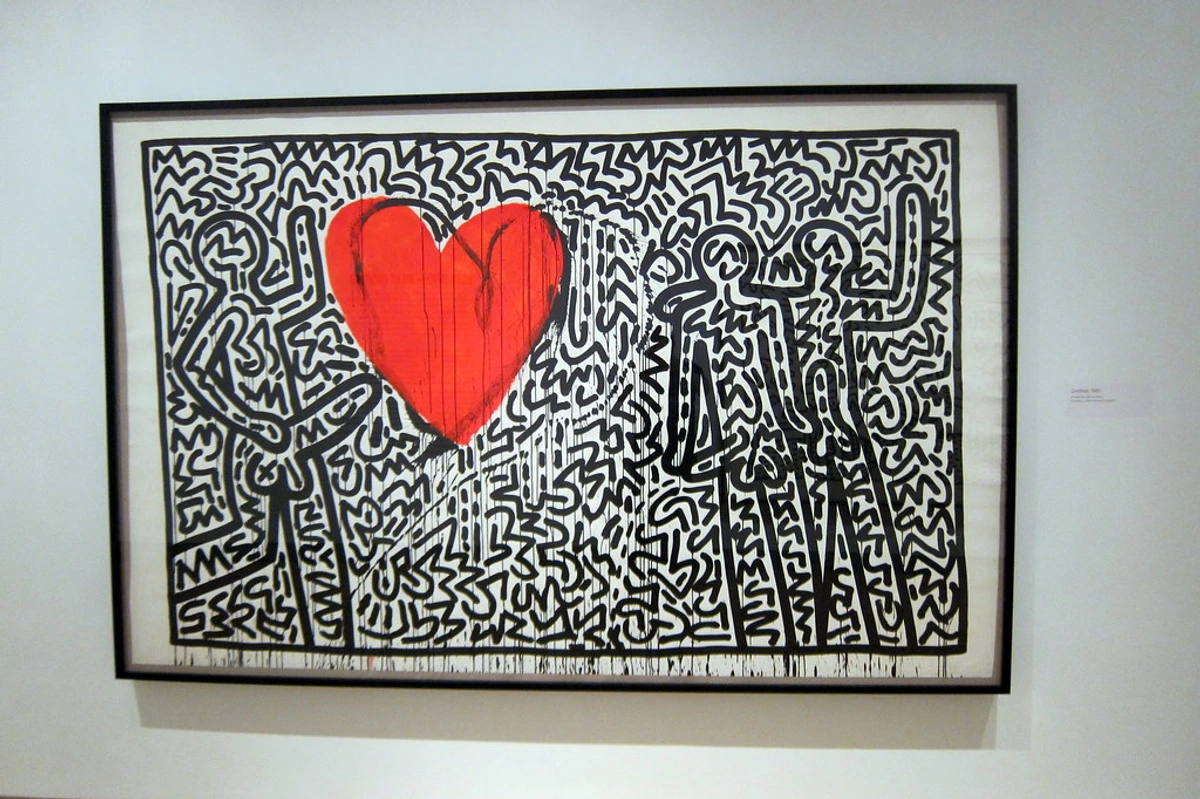

Consider Jean-Michel Basquiat's raw energy, drawing from graffiti and popular culture elements, transforming them into complex narratives that echoed Pop Art's accessible yet critical stance. Or Keith Haring's accessible iconography, taking his vibrant, public art into galleries and museums, making art for everyone. The spirit of Pop Art, celebrating the popular and making it art, lives on in contemporary graphic design (think bold, retro-inspired fonts and layouts), fashion (with its embrace of pop culture icons and vibrant colors), digital art, music album covers, film posters, and even meme culture. Yes, meme culture itself, with its rapid appropriation, recontextualization, and mass dissemination of imagery for commentary or humor, can be seen as a direct, digital descendant of Pop Art's core tenets. Look around; the visual language of Pop Art is still embedded in our everyday!

It's also worth noting the significant commercial success Pop Art achieved. This wasn't just art for the critics; it was art that captivated the public and sold, challenging the romanticized notion of the struggling, misunderstood artist. Its accessibility, novelty, and connection to celebrity and consumer products made it incredibly marketable. Warhol's Campbell's Soup Cans, for example, became so iconic they were sometimes mistaken for actual product labels, blurring the line between art and everyday commodity. In a delicious twist of irony, the very art that critiqued consumerism often became a highly sought-after commodity itself, a complex reflection of its own themes. While some critics argue that by embracing consumerism, Pop Art inadvertently legitimized or even glorified it, its commercial viability further propelled its influence, making art a more tangible and accessible part of daily life for many. This commercial success also had a profound impact on the gallery system, forever intertwining art's market value with its popular appeal – a shift that continues to redefine the art world today. (And yes, the irony of an artist discussing art's commercial success while running a website to buy art is not lost on me – perhaps Pop Art's influence runs deeper than I sometimes realize, even manifesting in my own business model!)

Pop Art also subtly changed our perspective on consumerism itself. By holding up a mirror to our obsession with brands and celebrities, it forced us to confront the very fabric of our modern existence. It's a movement that, for me, always feels fresh, relevant, and a little bit mischievous. Its spirit of playful defiance reminds me of the power of observation and the beauty hidden in plain sight, a journey I continuously explore in my own artistic timeline. If you, like me, find inspiration in art that challenges perceptions and connects with the immediate world, I invite you to explore my own collection to buy. Perhaps you'll find a piece that sparks a similar sense of vibrant recognition and playful defiance in your own space.

My Final Reflections: A Personal Connection to Pop Art's Enduring Spirit

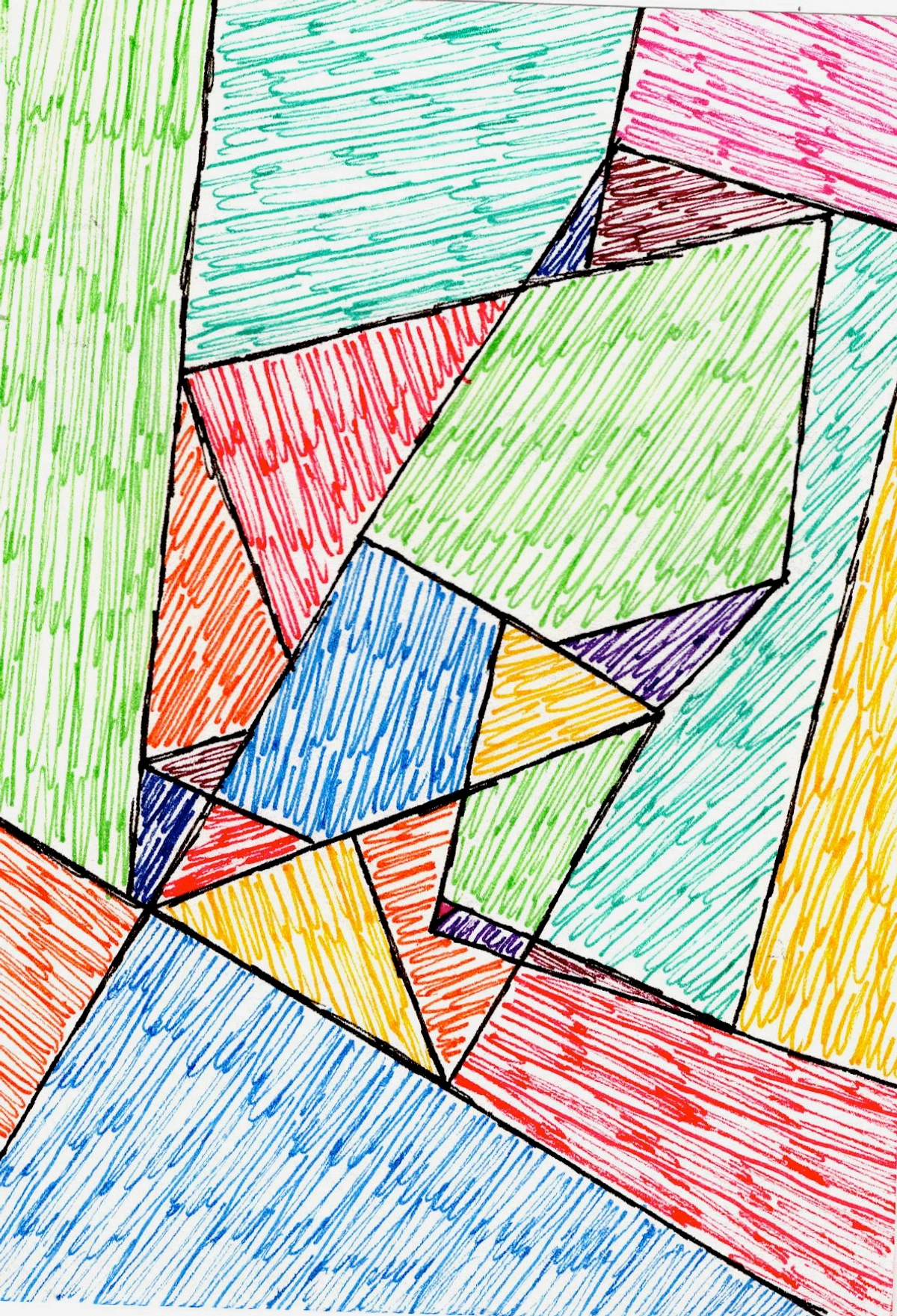

Pop Art taught us that art can be inclusive, that it can comment on society, and that profound impact doesn't always require deep intellectualism. Sometimes, a bold statement on a canvas is enough. This philosophy deeply resonates with my own approach to creating art. I believe that art should be accessible and enjoyable for everyone, not just those with a specific academic background. My own abstract and geometric pieces, while distinct, share that bold energy and directness. Just like Pop Art found beauty and meaning in the mundane, I often find inspiration in the overlooked patterns and vibrant energies of the world around us. This willingness to challenge artistic norms and focus on immediate visual impact is something I deeply connect with in my own work. My compositions often utilize bold lines and vibrant color blocking that, while not directly appropriating commercial imagery, certainly echo the graphic power and immediate recognition that Pop Art celebrated. The spirit of playful defiance, the focus on striking visual impact, and the desire to make art engaging and approachable for all – these are the threads that connect my abstract explorations to the Pop Art movement. Whether you're admiring a piece in a grand museum like my own 's-Hertogenbosch museum' or choosing a print to buy for your home, the connection should be personal and immediate.

So, the next time you glance at a billboard, a product label, or even a comic strip, pause for a moment. You might just find a subtle nod to Pop Art, or perhaps, a spark of inspiration that challenges your own perceptions of what art truly is. What everyday objects in your life do you think hold artistic potential? And how do you think Pop Art's influence shows up in today's digital world?

Frequently Asked Questions About Pop Art

Q: What is Pop Art in simple terms?

A: Pop Art is an art movement that emerged in the mid-1950s, using imagery from popular culture such as advertising, comic books, and everyday objects as its subject matter. It aimed to challenge traditional art values by bringing art closer to everyday life, often using irony and appropriation. It's art that celebrated the popular and familiar.

Q: Who are the most famous Pop Artists?

A: The most famous Pop Artists include Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, Claes Oldenburg, James Rosenquist, Richard Hamilton (often credited with pioneering Pop Art in Britain), and Eduardo Paolozzi. Don't forget Robert Indiana, known for his iconic "LOVE" sculpture!

Q: When did Pop Art start and end?

A: Pop Art officially began in the mid-1950s in the United Kingdom and late 1950s in the United States. It peaked in the mid to late 1960s. While its most prominent period as a distinct movement waned by the early 1970s as new movements like Minimalism and Conceptual Art emerged, its "end" is more accurately described as a transformation rather than a cessation. Its aesthetic, conceptual approaches, and profound influence on graphic design, advertising, and contemporary art continue to be felt today, demonstrating an enduring legacy that far outlives its initial timeframe.

Q: Why is Pop Art important?

A: Pop Art is important because it challenged the elitism of fine art, effectively dismantling the rigid hierarchy between 'high art' and 'low culture'. It democratized art by making it accessible and relatable to the masses, and reflected (and commented on) the consumer culture of its time. It also heavily influenced subsequent art movements, graphic design, and advertising, proving art could be both profound and immensely popular.

Q: What artistic techniques did Pop Art often use?

A: Pop Artists frequently employed commercial art techniques, such as silkscreening (popularized by Andy Warhol for mass production), lithography, and the use of Benday dots (seen in Roy Lichtenstein's work to mimic comic book printing). They also utilized collage, appropriation, and sculpture, often on a monumental scale, embracing the mechanical and mass-produced aesthetic.

Q: Is my art Pop Art?

A: While I love bold colors and dynamic compositions, my art, often abstract and geometric, tends to lean more into a contemporary expression that draws from different influences. The spirit of Pop Art's accessibility and engaging visual language is certainly present, particularly in my use of bold lines, vibrant color blocking, and a focus on immediate visual impact. However, its thematic focus on direct commentary on consumer culture and explicit appropriation of commercial imagery is less central to my work. Instead, my pieces often explore internal emotional landscapes or abstract structural relationships, delving into the interplay of color, form, and personal feeling rather than critiquing or celebrating mass-produced imagery. This offers a different kind of dialogue while still aiming to be universally engaging and deeply personal. If you enjoy bright, engaging pieces that spark conversation, you might find something you love in my collection to buy!