Symbolism Art Movement: Unveiling Inner Worlds & Enduring Legacy

Explore the Symbolism art movement's rebellion against realism, its mystical origins, and philosophical roots. Discover key artists like Moreau, Redon, and Gauguin, their focus on dreams and subconscious emotion, and how its enduring legacy shapes modern art and the artist's own abstract work, inviting you to connect with the soul's whispers.

Symbolism Art Movement: Unveiling the Soul's Whispers & My Creative Echoes

Sometimes, the modern world feels like an endless scroll of reality TV – all surface, all literal, with little room for the mysteries that truly move us. It's as if we've forgotten how to dream with our eyes wide open, how to find meaning beyond the obvious. This fixation on the tangible was my default for a long time. But then, you start looking a bit deeper, don't you? You realize the most profound truths aren't always shouting from the rooftops; sometimes, they're just a whisper in the wind, a strange feeling you can't quite articulate. It was in this search for something more, this yearning for the profound, that I discovered the Symbolism art movement. It felt like stumbling into a quiet, dimly lit room filled with secrets – a sanctuary where imagination wasn't just permitted, but revered as the ultimate truth. This, dear reader, is the very essence of Symbolism: art’s elegant, often melancholic, rebellion against the mundane, a dive into the deep, swirling currents of the human psyche, and a journey into the unseen truths that shape our inner worlds.

The Whispers of the Soul: What is Symbolism?

Imagine the late 19th century. Impressionism was all the rage, capturing fleeting moments of light and color. Realism insisted on showing life exactly as it was, warts and all. And then, a group of artists, writers, and poets in France and Belgium collectively sighed, rolled their eyes, and decided: "Enough! There's more to life than what we see." This introspective yearning, this profound whisper, resonated deep within me, pulling me towards something more meaningful than mere observation. It felt like a quiet rebellion against the clamor of a world increasingly fixated on industrial progress, empirical science, and superficial appearances – a world where the soul's voice risked being drowned out by the relentless march of modernity, the rise of photography seemingly rendering objective painting redundant, and the embrace of positivism.

Symbolism emerged as a profound counter-movement, rejecting the superficiality of the material world and the objective observation of Impressionism. It wasn't interested in what was seen, but why it was felt and how it resonated within. Instead, these artists turned inward, seeking to express absolute truths, emotions, and philosophical ideas through indirect, suggestive means. They weren't painting the world as it appeared; they were painting the world as it felt – or as it dreamed. It was a glorious, often moody, declaration that art should be a window to the soul, not a mirror to nature.

Feature | Impressionism / Realism | Symbolism |

|---|---|---|

| Focus | Objective reality, external world, fleeting moments | Subjective reality, inner world, universal truths |

| Subject Matter | Everyday life, landscapes, portraits (as seen) | Dreams, myths, allegories, emotions, spirituality, occult |

| Style | Visible brushstrokes, natural light, accurate representation | Non-naturalistic colors, suggestive forms, ambiguity, distortion |

| Goal | Capture the visible, document the moment | Evoke feeling, suggest meaning, access the subconscious |

A Tapestry of Dreams: Origins and Philosophical Underpinnings

The roots of Symbolism are deeply entwined with a philosophical current that emphasized spirituality, mysticism, and the subconscious. While Impressionism and Realism captured the world 'as it was,' Symbolism sought the world 'as it felt,' drawing upon a rich history of intellectual and artistic precursors. Think of Romanticism of the early 19th century, with its fervent emphasis on emotion, imagination, individualism, and the sublime power of nature. Romantic artists and poets paved the way by prioritizing inner experience over objective reality, setting the stage for Symbolism's profound introspection. This yearning for belief, a desire to reconnect with something timeless and profound in a rapidly modernizing, secularizing world, fueled their artistic rebellion. They embraced the idea that the visible world was merely a veil, and true reality lay beneath, accessible through intuition, dreams, and symbols. Beyond Western philosophy, an increasing interest in Eastern philosophies and esoteric traditions, such as Theosophy, also offered Symbolists alternative frameworks for understanding hidden spiritual truths and the interconnectedness of all things, further fueling their pursuit of the unseen. We can even trace some shared sensibilities to the British Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, who, while earlier, also imbued their naturalistic details with symbolic meaning and drew heavily from literary and mythological narratives to explore moral and spiritual themes.

The Philosophical Undercurrents

This wasn't just an artistic choice; it was an existential one. Symbolists believed art could convey profound, ineffable truths that science or pure reason could not. They found intellectual kinship in the works of philosophers and writers who dared to plumb the depths of human experience and the mysteries of the mind.

Arthur Schopenhauer, with his ideas on the suffering inherent in existence and the power of will – a blind, irrational, and insatiable driving force behind all reality – resonated deeply with the Symbolists' melancholic and introspective leanings. His philosophy manifested in art that explored themes of fate, despair, and the inescapable human condition through often dark and contemplative imagery, validating their focus on internal struggles and the emotional weight of life.

Friedrich Nietzsche, too, with his exploration of the Apollonian (order, reason) and Dionysian (chaos, passion) aspects of human nature, provided a powerful framework. He urged artists to delve into the irrational and primal forces of the subconscious, embracing emotion and instinct over pure intellect. This was reflected in the often unrestrained emotionality, symbolic intensity, and rejection of traditional narratives found in their work, a direct challenge to the rationalism of their age.

Further intellectual currents shaped the Symbolist landscape. The morbid romanticism and exploration of the macabre found in the works of Edgar Allan Poe offered a literary blueprint for delving into psychological darkness and the supernatural, influencing Symbolists' fascination with death, mystery, and altered states. French poets like Stéphane Mallarmé and Paul Verlaine pushed the boundaries of poetic expression towards the evocative and symbolic, deeply influencing the Symbolists' quest for deeper truths through suggestion rather than direct statement.

Key Literary and Artistic Voices

These philosophical currents found potent expression in the works of key literary and artistic voices of the era, each translating the Symbolist ethos into their unique visual language.

Charles Baudelaire's poetry, particularly his concept of "Correspondences" where senses intermingle and the natural world acts as a "forest of symbols," was foundational. It provided a literary blueprint for the Symbolists' visual approach to synesthesia – the blending of senses – and the idea that deeper meanings are hidden just beneath the surface. Artists sought to create visual analogues for emotional states, using color, line, and composition to evoke a 'correspondence' with an inner spiritual reality. For instance, a specific shade of blue might not just depict the sky, but simultaneously evoke the profound melancholy of a rainy day and the faint scent of damp earth, creating a multi-sensory emotional experience for the viewer that directly links the physical to the metaphysical. This idea of seeing and feeling the world as a complex, interconnected web of sensory and spiritual data is something I constantly chase in my own abstract work, trying to make a visual 'smell' or a 'sound' out of color.

Key figures like Gustave Moreau conjured opulent, often unsettling mythological scenes, not to illustrate a story literally, but to evoke a sense of fatalism, moral decay, and hidden desires. His work, like "The Apparition" (also known as Salome Dancing), drips with symbolic meaning, forcing the viewer to confront the unseen, often exploring themes of sin, temptation, and the enigmatic 'femme fatale', depicting Salome as a powerful yet destructive force. Moreau's intricate details and rich colors served to create an atmosphere of mysterious grandeur rather than a mere biblical illustration.

/finder/page/symbolism-movement-mystical-poetic-art, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Odilon Redon, perhaps my personal favorite for his ethereal, often unsettling charcoal drawings and pastels, famously stated his goal was "to place the logic of the visible at the service of the invisible." He pulled imagery from dreams, nightmares, and the subconscious, creating works that hover between beauty and unease, such as his captivating "The Cyclops". Redon's approach was often more introspective and dreamlike than Moreau's grand historical tableaux, focusing on singular, haunting figures or eyes floating in abstract space.

![]()

/finder/page/symbolism-movement-mystical-poetic-art, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Other significant artists further diversified the Symbolist landscape. Arnold Böcklin, whose "Isle of the Dead" is the epitome of atmospheric melancholy, invited endless contemplation of mortality, often employing stark, isolated landscapes where cypress trees overtly symbolize death and mourning due to their ancient association with cemeteries and funerary rituals. Fernand Khnopff explored enigmatic silence and introspection, often depicting figures lost in thought or dreaming. His highly refined works, such as "I Lock My Door Upon Myself" often feature sphinxes (embodying mystery, fate, and enigma), isolated, androgynous figures, or mirrors (potent symbols of reflection, illusion, or introspection, sometimes even portals to other realities), embodying mystery and the subconscious, presented with a cool, detached precision.

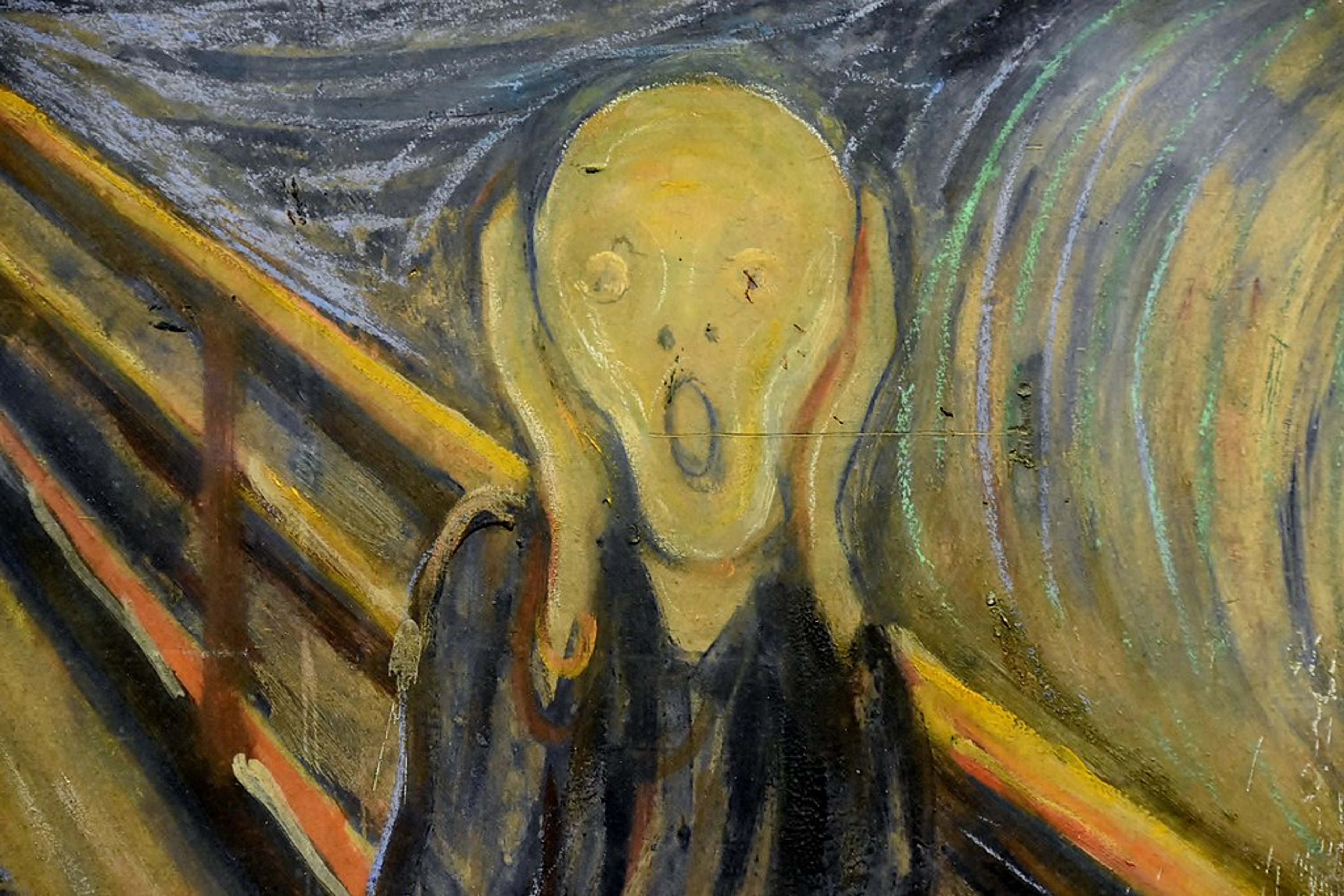

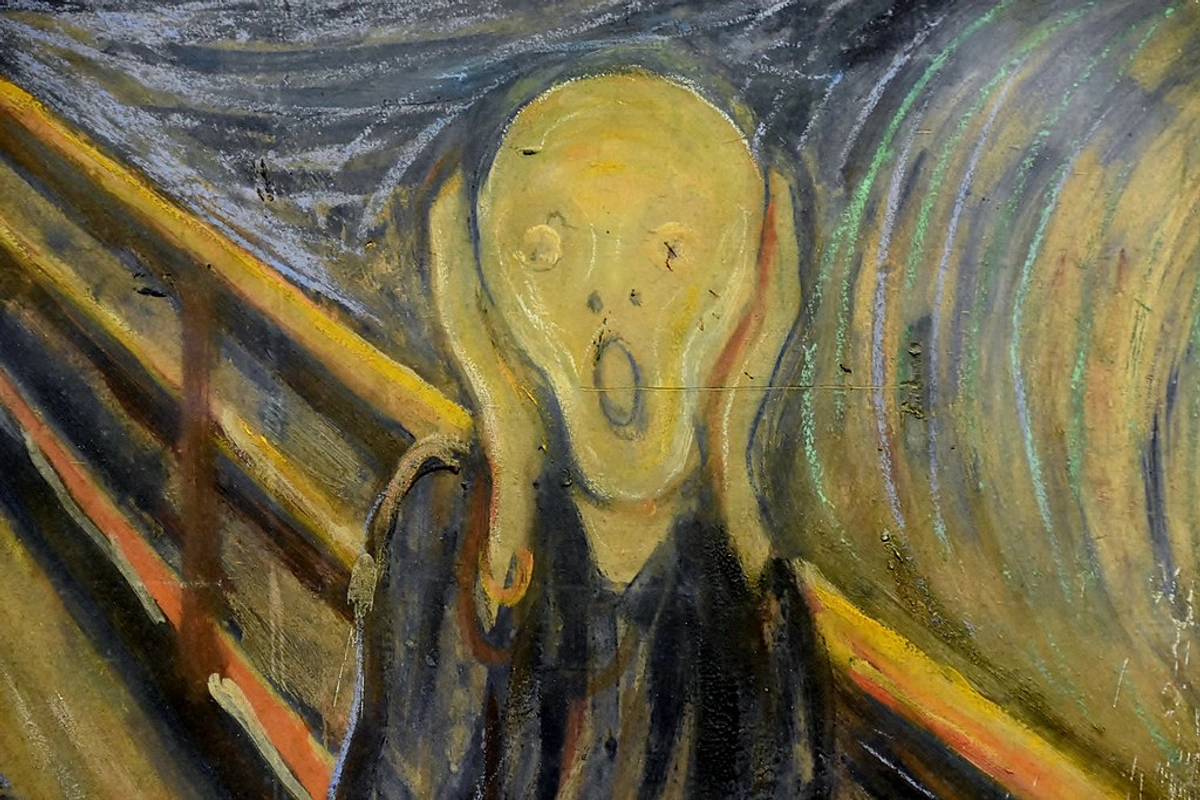

While often seen as a bridge to Expressionism, Edvard Munch's profound psychological depth and existential angst, famously captured in "The Scream", owes a clear debt to Symbolism's focus on inner subjective experience, depicting raw emotions like fear and despair through highly expressive, almost visceral, forms.

Another significant voice, though often categorized slightly differently, was Paul Gauguin. While not strictly a Symbolist, his "Synthetism" was a distinctive approach that deeply resonated with, and in many ways, responded to Symbolist ideals. It sought to express subjective emotions and ideas rather than objective reality, emphasizing the synthetic combination of observation, memory, and feeling. Unlike some Symbolists who relied on literary allegories, Gauguin used bold, non-naturalistic colors and flattened forms, often outlined with dark contours, to create symbolic rather than descriptive effects. He consciously rejected optical realism and the fleeting impressions of Impressionism, drawing heavily on indigenous cultures for symbolic inspiration, aiming to convey the 'inner truth' of his subjects and aligning perfectly with the Symbolist quest for deeper meaning beneath the surface. It's an important distinction that his approach was a direct engagement with the Symbolist challenge to realism.

These artists were less concerned with narrative clarity and more with creating an atmosphere, a mood, a psychological resonance. They wanted to shake you out of your complacent view of reality and nudge you towards something deeper, something perhaps a little uncomfortable but undeniably true. This collective pursuit of the unseen and felt laid the groundwork for the movement's unique aesthetic principles.

Beyond the Visible: Mystical and Poetic Aesthetics

But how did these artists manage to capture the intangible, the whispers of the soul? It wasn't about literal representation. Instead, Symbolists employed a range of aesthetic principles:

- Suggestion and Ambiguity: Rather than explicit statements, they hinted at meaning, inviting the viewer to engage in an inner dialogue. The ambiguity was deliberate, allowing for multiple, personal interpretations. Think of a veiled figure, its identity obscured, inviting your fears or desires to project upon it. This deliberate obscurity encouraged a deeper, more personal engagement than the straightforward narratives of Realism.

- Allegory and Myth: They drew heavily from mythology, religion, and folklore, not as historical records, but as vessels for universal human experiences and archetypal symbols. Common archetypes included the enigmatic femme fatale (a seductive, dangerous woman embodying temptation and destruction, often seen in works featuring Salome or Judith), the Sphinx (embodying mystery and fate), Orpheus (representing the artist's suffering or the power of music), and various religious or occult figures. These ancient narratives provided a ready-made vocabulary for the unseen, allowing artists to explore complex human conditions through established, resonant figures.

- The Power of Color and Line: Color wasn't used descriptively but expressively. Vibrant hues or muted palettes were chosen for their psychological and emotional impact, creating specific moods. Deep blues often evoked mystery or spirituality, greens suggested decay or rebirth, and gold hinted at the divine or opulence. Lines could be sinuous and organic, echoing the fluidity of dreams, or stark and unsettling, reflecting anxiety. This idea of color as an emotional language deeply resonates with my own work, where I strive to convey feeling through vibrant palettes. You can dive deeper into how color speaks in my article on the emotional language of color in abstract art.

- Distortion and Exaggeration: Figures and forms were often distorted or exaggerated to emphasize emotional states rather than physical accuracy, laying groundwork for future movements like Expressionism. This departure from naturalistic representation allowed for a more direct emotional impact.

- Symbolic Objects and Motifs: Beyond archetypal figures, specific objects and motifs were frequently imbued with layered meanings, inviting viewers to decode their hidden messages. Lilies, for instance, often symbolized purity due to their association with the Virgin Mary, but in a Symbolist context, they could also hint at death or fleeting beauty, much like their appearance in Pre-Raphaelite works by artists like Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Peacocks, with their ostentatious tail feathers, frequently represented vanity, pride, or immortality, famously used by James McNeill Whistler in his 'Peacock Room.' Mirrors served as potent symbols of reflection, illusion, or introspection, sometimes even portals to other realities, as seen in Khnopff's introspective portraits. These visual cues, deeply embedded in cultural consciousness, allowed artists to communicate complex, often subconscious, ideas without explicit narrative.

The connection to poetry was paramount. Symbolist poets like Stéphane Mallarmé and Paul Verlaine sought to evoke rather than describe, to suggest rather than state directly, echoing the artists' visual approach. This quest for deeper truths through suggestion and atmosphere also extended to their theatre. Plays by Maurice Maeterlinck, with their sparse dialogue and focus on premonition and inner lives, exemplify Symbolist theatre, sharing the goal of accessing profound emotional and spiritual realities rather than literal narrative.

Music, with its abstract emotional power, was a significant inspiration. Composers like Richard Wagner, whose "total art work" (Gesamtkunstwerk) aimed to unite music, drama, and visual elements to create an immersive, spiritual experience, greatly influenced the Symbolists' holistic aspirations. They saw the Gesamtkunstwerk as a model for how art could transcend individual mediums to create a unified, deeply moving spiritual experience. Artists aimed to translate musical principles—like harmony, dissonance, rhythm, and emotional crescendo—into visual compositions, using color and line to create a similar emotional resonance. Claude Debussy and Frédéric Chopin also created works that evoked moods and emotions without explicit narratives, offering a model for how art could speak directly to the soul. Just like music, Symbolist art aimed to bypass intellectual understanding and go straight for an emotional resonance. It's a journey into the soul, where the art isn't just observed, but felt. What hidden symphonies do these canvases play for you?

My Own Poetic Dance: Symbolism in My Art

Having explored the historical roots and aesthetic principles of Symbolism, I find myself drawn to its enduring spirit, which echoes profoundly in my own contemporary artistic journey. When I think about the Symbolists, I see a kindred spirit, though perhaps a slightly less melancholic one. While I appreciate the profound contemplation in Böcklin's 'Isle of the Dead,' I confess I often prefer my artistic islands with a bit more of a vibrant, living energy! My own abstract art, while miles away in style, shares that deep-seated desire to explore the invisible. I'm fascinated by how we decode personal narratives and infuse meaning into abstract forms, much like the Symbolists used their own visual vocabulary to hint at deeper truths. It's about creating art that resonates not just with the eye, but with the heart and the subconscious.

It's a journey into decoding the personal symbolism and narratives within my work. I might not be painting mythical beasts or allegories of sin, but I'm certainly chasing feelings, dreams, and that strange, indefinable pull of the subconscious. My colors are often bold, my lines sometimes chaotic, yet always striving to evoke an emotion, a memory, or a sense of peace – or perhaps a wonderfully unsettling blend of all three. Sometimes, I find myself staring at a blank canvas, grappling with a feeling I can't name – a specific kind of longing, or a fleeting memory. Instead of trying to literally depict it, I let the colors guide me, allowing a deep blue to bleed into a fiery orange, creating a contrast that feels like that unnameable emotion, much like a Symbolist might use a particular myth to tap into a universal human experience.

For instance, a piece like "The Watchful Eye" (referring to the image used here) functions much like a Symbolist archetype. The recurring motif of a singular, intense blue eye in many of my pieces is not a literal representation but an evocative symbol, often representing introspection, the 'inner gaze,' or a watchful presence. It invites the viewer to look inward themselves and project their own meaning onto it, much as Redon's haunting figures prompt personal interpretation. It's about creating a space where you, the viewer, can bring your own story, your own feelings, and complete the artwork with your unique inner world – a direct echo of Symbolism's call for personal interpretation and connection to the invisible.

My abstract self-portraits, for example, often forgo physical likeness to instead explore my inner world and aspirations through a tapestry of colors and patterns. Like a Symbolist might use a particular myth, I use specific hues and textures to represent my spiritual journey or emotional state, aiming for an abstract depiction of the soul rather than the body. It’s an exercise in placing "the logic of the visible at the service of the invisible," much like Odilon Redon aimed to do, turning the canvas into a mirror of the mind rather than just the world.

The Enduring Echoes: Symbolism's Legacy

The Symbolist movement, though relatively short-lived in its purest form, cast a long, shadowy, and utterly fascinating influence over subsequent art history. It was a crucial bridge from the visible world of the 19th century to the fragmented, internal landscapes of the 20th. Its ideas spread beyond France and Belgium, influencing groups like the Vienna Secession (with artists like Gustav Klimt, whose opulent, gilded works and use of allegorical figures perfectly marry Symbolist mysticism with decorative arts) and the Nabis in France. The Nabis, meaning "prophets" in Hebrew, emphasized spiritual and personal expression, simplifying forms and using bold, flat colors not for realism but for their symbolic and decorative impact, heavily influenced by Gauguin's Synthetism and Symbolist ideals. Furthermore, Symbolism resonated across Europe, giving rise to distinct movements such as Russian Symbolism (featuring artists like Mikhail Vrubel, known for his mystical, often demonic, and richly textured imagery) and Scandinavian Symbolism (as seen in the early works of Edvard Munch and Akseli Gallen-Kallela, who explored Finnish folklore and national myths), demonstrating its widespread impact on European art.

Think of it: without Symbolism's insistence on emotional truth over visual accuracy, and its embrace of distortion for expressive purposes, would we have had the intense psychological drama of Expressionism? Symbolism’s deep dive into the subconscious, dreams, and the irrational provided fertile ground for Surrealism to blossom, plumbing even greater depths of the human psyche by exploring automatism, dreamscapes, and irrational juxtapositions. Even early Abstract Art, with its focus on pure form and spiritual essence (as seen in the early theories of Wassily Kandinsky), owes a quiet nod to the Symbolists' pioneering exploration of the non-representational and the inner world. They cracked open the door to a universe where art wasn't just about showing, but about feeling and knowing on a deeper, almost mystical level. For a broader look at how these movements connect, check out the ultimate guide to abstract art movements. You can also explore understanding symbolism in contemporary art.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Edvard_Munch,_The_Scream,_1893,National_Gallery,Oslo%281%29%2835658212823%29.jpg, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0

Symbolist artists also sometimes experimented with specific materials and techniques to enhance the evocative quality of their work. They often favored tempera, pastels, or watercolor for their soft, luminous, or ethereal qualities, which lent themselves well to dreamlike or mystical subjects, in contrast to the more robust oil paints of Realism. The meticulous detail found in many Symbolist works, particularly those by Moreau and Khnopff, also served to create a sense of otherworldly precision, drawing the viewer deeper into their carefully constructed symbolic realms. While facing criticism for its perceived obscurity and elitism, Symbolism also found early champions among progressive critics and collectors who recognized its revolutionary potential to redefine art's purpose beyond mere imitation, celebrating its courageous dive into the inner life.

Frequently Asked Questions about Symbolism in Art

Here are some common questions to deepen your understanding of this fascinating movement:

Q: What was the main goal of the Symbolism art movement?

A: The main goal of Symbolism was to move beyond mere representation of the visible world to express deeper truths, emotions, and ideas through evocative symbols, myths, and the exploration of the subconscious. It sought to capture inner, subjective realities, emphasizing the spiritual and mystical over the material.

Q: What were common themes explored by Symbolist artists?

A: Symbolists frequently explored themes such as death, sin, eroticism, dreams, the occult, mysticism, mythology, religious experience, the exotic, and the enigmatic figure of the 'femme fatale.' They delved into the darker, more mysterious aspects of the human condition, often with a sense of melancholic introspection.

Q: How did Symbolism differ from Impressionism?

A: Impressionism focused on capturing fleeting moments of light and color in the objective, external world, emphasizing optical perception. Symbolism, by contrast, rejected this objectivity, turning inward to explore subjective emotions, dreams, and spiritual realities, using color and form for expressive, not descriptive, purposes. Symbolism sought deeper meaning, while Impressionism sought visual immediacy.

Q: What materials and techniques did Symbolists commonly use?

A: Symbolist artists often preferred mediums like tempera, pastels, and watercolor for their ability to create soft, luminous, and ethereal effects, which were well-suited to their dreamlike and mystical subject matter. They also employed meticulous detail and rich, non-naturalistic color palettes to enhance the evocative and symbolic qualities of their work, moving away from the more direct, robust oil painting techniques of Realism.

Q: How did Symbolism influence later art movements like Expressionism and Surrealism?

A: Symbolism's rejection of objective reality and its deep exploration of the subconscious, dreams, and emotional truth laid crucial groundwork for 20th-century art. Its use of distortion and non-naturalistic color for expressive purposes directly foreshadowed Expressionism's intense psychological drama. Similarly, Symbolism's fascination with the irrational and inner worlds paved the way for Surrealism's exploration of the dream state and the subconscious, making it a vital bridge from 19th-century traditions to modern art.

Q: Who were some key Symbolist artists?

A: Key Symbolist artists included Gustave Moreau, Odilon Redon, Arnold Böcklin, Fernand Khnopff, Paul Gauguin (with his Synthetism), and Edvard Munch (often seen as a bridge to Expressionism), as well as Gustav Klimt (with his highly decorative and symbolic later work), Mikhail Vrubel, and Akseli Gallen-Kallela.

Q: What were the typical visual characteristics of Symbolist art?

A: Symbolist art often featured rich, non-naturalistic color palettes used for strong emotional impact, sinuous and organic lines, flattened forms, and often highly detailed, dreamlike compositions. It frequently incorporated archetypal figures, mythical creatures, and symbolic objects (like lilies or peacocks) to convey layered meanings, all serving to evoke mood, mystery, and inner experience rather than objective reality. A sense of quiet contemplation or unsettling unease is also common.

Q: What was the geographical reach of the Symbolism movement?

A: While originating primarily in France and Belgium, Symbolism had a significant international impact. Its influence spread across Europe, giving rise to distinct national expressions such as Russian Symbolism (Mikhail Vrubel), Scandinavian Symbolism (Edvard Munch, Akseli Gallen-Kallela), and inspired groups like the Vienna Secession (Gustav Klimt) in Austria, demonstrating its widespread resonance and adaptability to local artistic traditions.

Q: What criticism did Symbolism face during its time?

A: Symbolism was often criticized for its perceived obscurity, elitism, and pessimism. Critics sometimes found its themes too morbid, its imagery too ambiguous, or its rejection of traditional narrative confusing, contrasting sharply with the more accessible realism and Impressionism of the era. Its introspective nature was also sometimes seen as a retreat from modern life.

Q: Does Symbolism still influence contemporary art?

A: Absolutely! While the movement itself faded, its core principles – the exploration of personal narratives, the use of symbols, the focus on emotional and psychological depth, the rejection of pure realism, and the interest in the subconscious – continue to resonate profoundly. You can see its echoes in contemporary abstract and conceptual works, certain forms of surrealism, dark academia aesthetics, and even in digital art that seeks to evoke moods or hidden meanings rather than literal representation. To learn more, check out understanding symbolism in contemporary art.

Q: How can I best appreciate Symbolist art?

A: To truly appreciate Symbolist art, approach it with an open mind and a willingness to engage with its ambiguity. Don't look for a literal story; instead, allow the colors, forms, and imagery to evoke feelings, memories, or thoughts within you. It's an invitation to introspection, a personal dialogue between you and the artwork – a chance to connect with those quiet whispers of the soul it was designed to awaken. What hidden meanings might you discover within its depths?

Finding Your Own Symbols

Ultimately, Symbolism reminds us that art isn't just about what you see on the canvas; it's about what it awakens within you. It’s about the stories, the feelings, the quiet whispers of belief that resonate from the work and into your own soul. It’s a powerful testament to the idea that the most profound truths often lie just beyond what our eyes can see, waiting for us to dream them into being. Indeed, inviting that personal, internal dialogue is perhaps the most profound kind of art there is, and a legacy that continues to inspire artists, including myself, today.

If you're curious to see how these ideas translate into my contemporary abstract work, feel free to explore my latest creations. Or, if you're ever in 's-Hertogenbosch, I'd love for you to visit my museum and experience the conversation between art and observer firsthand. You can also discover my artistic journey to see how my path has led me to these explorations of the unseen. For in the end, perhaps the greatest symbol of all is the one you discover within yourself.