My fascination with observing strangers, not in a peculiar way, but with a quiet, internal wonder about their stories and essence, is the very spark that ignited my lifelong passion for portraiture. It’s a deep-seated human curiosity—to capture and understand a face, or even just the echo of a soul, and it’s precisely why portraiture, in all its fascinating forms, has captivated me for so long. It’s far more than just rendering a likeness; it’s an ambitious attempt to bottle a soul, or at least a significant moment in its journey – a quest to make the invisible inner world visible. Though, speaking from personal experience, sometimes it’s just about getting the nose right, which is notoriously difficult. This journey through portraiture isn't merely an art history lesson; it's a powerful mirror reflecting how humanity has grappled with identity, status, connection, social norms, and even propaganda across millennia. As an artist, I constantly wrestle with what it truly means to 'see' someone, and how to convey that understanding on a canvas, even when no literal face is present. Different artistic mediums – from the chisel to the digital brush – have uniquely shaped this quest, continuously pushing the boundaries of how we define and capture 'self'. We’ll journey through these eras, seeing how the gaze has evolved, what it has revealed, and what it still seeks to find in the human spirit.

What is Portraiture, Really? Beyond the Likeness

When you hear 'portrait,' you probably picture a painting or photograph of someone's face. While that's the common understanding, for me, it's always been about something far deeper. Portraiture, at its core, is the deliberate attempt to capture personality, status, emotion, and the intricate relationship between the subject and their world. It transcends traditional mediums, encompassing sculptures, drawings, digital avatars, and even performance art. Think of it as a visual autobiography, but narrated and interpreted by the artist, who actively endeavors to reveal the subject's internal world. Historically, portraits haven't just been about commemoration or identification; they've served as powerful tools of propaganda, asserting power and ideology. Consider the grandeur of Napoleon's official portraits by Jacques-Louis David, crafted to project an image of infallible leadership, or the stylized, heroic depictions of Soviet leaders, designed to reinforce state ideology and inspire unwavering loyalty. They also functioned as symbols of social mobility for the aspirational, allowing them to visibly assert their rising wealth, education, or connections within society. This historical function of portraiture as a tool for shaping perception and identity is something I deeply resonate with, even in my abstract work, where I aim to evoke a similar sense of presence and internal narrative. Portraits offer a unique window into society's values, often revealing less about who a person truly is, and more about what they represent – a public persona, a role, or an ideal. This very idea of revealing an internal world, even without a literal face, is a core pursuit in my own abstract art, where I strive to infuse vibrant colors with emotion and presence, capturing the echo of a soul without a literal depiction. From ancient pigments and stone to modern digital art and mixed media, the evolution of materials and techniques continually expands how we express the human condition and grapple with identity, often reinforcing or challenging existing social norms. You can explore how feelings guide my own brushstrokes and the emotional resonance of my abstract art here.

The Dawn of the Gaze: Ancient Roots

But how did this profound human fascination with capturing an essence truly begin? Our journey into portraiture stretches back millennia, long before selfies or even mirrors were common. Before even formal portraits, humans made their mark: early forms of self-representation can be traced back to prehistoric cave paintings or small carved figures that hinted at human form, albeit often in a collective or symbolic sense rather than individual likeness. These were primal urges to assert presence.

In Ancient Egypt, pharaohs and nobles commissioned sculptures (often from durable stone like granite, schist, or basalt) and paintings (frescoes on tomb walls) primarily to preserve their eternal spiritual essence, the 'Ka' or life force, ensuring their existence in the afterlife. These weren't about vanity; they were existential safeguards, securing a place beyond the mortal coil, often shaped by strict conventions of the patron's desired depiction rather than pure likeness. There was an ethical dimension even then: the right to be portrayed was a mark of status, and controlling one's image (even after death) was a form of power. Similarly, in Mesopotamia, votive figures with enlarged eyes were sculpted not just as likenesses, but as perpetual stand-ins, praying on behalf of the worshipper in the temple – a form of spiritual presence, long before individual identity was the primary focus. Beyond these, diverse non-Western traditions also sought to capture a person's spirit, lineage, or social role. Consider the intricate ancestor portraits of East Asia, often rendered with delicate ink on silk or paper, which captured not just a likeness but the spiritual continuity of a family, or the detailed, narrative portraiture found in Indian miniature painting, using mineral pigments and gold to convey identity through rich storytelling.

The Romans, ever pragmatic, advanced the concept with incredibly realistic busts (often in marble, sometimes bronze), almost like early identity cards. These imagines maiorum preserved the memory of ancestors and were powerful public statements, adorning forums and villas as symbols of civic pride and dynastic power. I sometimes wonder if they considered, 'Will people truly remember me just from this stone face, or will they just think I had a very specific nose?' These highly detailed, often unflattering, portraits aimed to convey gravitas and wisdom, reinforcing the social hierarchy and the importance of family lineage. Their functional role in society was paramount, serving as tools for public memory and political statement, not merely decoration.

In Ancient Greece, the initial focus was often on idealized forms reflecting arete (excellence or virtue, often expressed as physical perfection). Yet, true individual portraiture slowly began to emerge, particularly with figures like Socrates, whose distinctive, non-idealized features were embraced, and Alexander the Great, whose portraits captured his charismatic presence rather than just generic heroism. This blend of the universal ideal and the emerging individual spirit reflects humanity’s evolving self-perception – a fascinating internal struggle, much like I sometimes feel in my own abstract art between conveying a universal emotion and a very specific personal experience. This era also quietly introduced ethical dimensions, as the right to portray or be portrayed often came with status and power, making these early images not just art, but declarations of social hierarchy and ownership of one's public face. The essential truth these ancient societies tried to preserve was often linked to spiritual continuity, social order, and the enduring legacy of their elites, setting the stage for the Renaissance's focus on the individual.

The Renaissance: Rebirth of the Individual

The Renaissance marked a seismic shift. As humanism flourished, the individual's importance surged, leading to an unprecedented demand for portraits. Wealthy patrons, burgeoning merchants, and even Popes commissioned artists (now with oil paints allowing for richer colors, smoother blending, and greater luminosity) to capture not just their likeness, but their newfound status, piety, and an almost palpable sense of self. It was about solidifying legacy, asserting one's place in a rapidly changing world, and even displaying one's moral virtue. For many, a commissioned portrait was a deliberate act of self-fashioning, a carefully curated public image designed for posterity and social advancement, often reinforcing prevailing social norms around wealth and piety. Portraits became a visible testament to one's achievements and social standing, a means of navigating the changing social landscape. This era also saw the rise of miniature portraits, small, portable, and intimate works, often painted on vellum or ivory, serving as tokens of affection or diplomatic gifts, a personal counterpoint to the grand public display.

Artists like Leonardo da Vinci revolutionized portraiture with his mastery of sfumato, a soft, hazy technique that allowed for incredibly subtle transitions between colors and tones. This created an unprecedented sense of life, depth, and psychological nuance, moving far beyond the flatter, more symbolic representations of the past. This mastery of sfumato, creating those incredibly subtle transitions that breathe life and psychological nuance into a subject, is a technique I constantly strive to emulate in my own work, seeking to imbue color with a similar depth of feeling. The Mona Lisa, with her enigmatic smile and piercing gaze, stands as the quintessential example – it’s not just a face; it’s a living, breathing psychology. Her subtle, almost imperceptible smile, achieved through the delicate blending of shadows around her mouth and eyes, invites endless interpretation, making her presence feel both intimate and elusive. Raphael imbued his subjects with an almost divine grace, while Titian brought a new richness of color and profound psychological depth to his sitters, often using vibrant glazes to achieve luminous effects. These masters weren't simply rendering faces; they were interpreting souls, using their mastery of light, shadow, and color to reveal inner psychology and social standing. It’s hard not to wonder if, during these sittings, they felt the immense pressure to capture something eternal, or perhaps just hoped their patron would settle their bills promptly – a timeless concern for any creator! How did this newfound emphasis on the individual in art shape society's view of itself and its aspirations, and how much of our own online presence today is a form of Renaissance-era self-fashioning, carefully curated for public view?

Baroque and Rococo: Drama, Grandeur, and Intimacy

Transitioning from the Renaissance's measured humanism, the Baroque era exploded with drama, emotion, and theatricality. Portraits became dynamic, often monumental, reflecting the grandeur of the Counter-Reformation and absolute monarchies. Artists often used oil on canvas, employing dramatic chiaroscuro (strong contrasts between light and dark) to heighten emotional intensity. Yet, within this public display, artists simultaneously delved deep into individual psyches. Rembrandt van Rijn, for instance, explored the human spirit with unparalleled sensitivity, his extensive self-portraits chronicling the raw, unvarnished journey of a man’s soul over decades, his masterful use of chiaroscuro illuminating every wrinkle and emotion. Rembrandt's raw, unvarnished journey of a man’s soul over decades, chronicled through his extensive self-portraits, is a profound testament to the power of self-reflection – a practice I find deeply inspiring as I explore my own inner landscape through my art. These powerful self-reflections established self-portraiture as a genre of profound introspection. Peter Paul Rubens, by contrast, painted robust, vibrant figures brimming with life and movement, often creating elaborate canvases that celebrated power and opulence for his royal patrons, reinforcing their authority and idealizing their public image with rich colors and dynamic compositions.

By sharp contrast, the Rococo period offered a lighter, more decorative, and often more intimate view, focusing on the refined pleasures of aristocratic life. This era saw a significant shift, moving from grand religious or royal figures to more candid portrayals of the aristocracy and, increasingly, the aspirational bourgeoisie. Portraits by artists such as Jean-Honoré Fragonard and François Boucher captured subjects in playful, luxurious, often flirtatious settings, emphasizing charm, romance, and a sense of carefree elegance. They utilized delicate pastel colors and soft, feathery brushwork, often on smaller canvases, creating an intimate, almost voyeuristic feel. While Rococo portraits offered an intimate glimpse into aristocratic leisure, my own work often seeks a more visceral, emotional intimacy, aiming to connect with viewers on a primal level. They were, in a way, early forms of self-therapy for the upper classes, allowing them to project an image of idyllic leisure and emotional freedom, often subtly challenging the rigid formality of earlier eras. This pendulum swing between public grandeur and private charm reveals a fascinating dichotomy in humanity's desire for connection and self-expression – a principle that continues to guide my own journey as an artist, where I strive to create visual storytelling through art. What do these vastly different aesthetics tell us about the eras' underlying values and how individuals sought to define themselves in a changing world, shifting towards a more intellectual and moral focus with the coming Neoclassicism?

Neoclassicism and Romanticism: Ideals and Emotions

The late 18th and early 19th centuries witnessed a profound swing towards Neoclassicism, a deliberate return to the classical ideals of order, clarity, and rational thought, often fueled by revolutionary fervor. Portraits of this era, exemplified by Jacques-Louis David, frequently depicted stoic, heroic figures, reflecting a powerful emphasis on civic virtue, duty, and an almost sculptural idealization. Artists focused on clean lines, balanced compositions, and muted palettes, utilizing techniques that conveyed dignity and timelessness, often reminiscent of ancient Greek and Roman sculpture. These portraits weren't just individuals; they were embodiments of an ideal citizen, often used as visual propaganda to inspire revolutionary or nationalistic sentiment, reinforcing new social ideals.

Then, almost as a visceral reaction, came Romanticism, a passionate rebellion against rigid classical forms. This movement celebrated emotion, individualism, the sublime, and a profound introspection into the human condition. Artists like Francisco Goya and Eugène Delacroix captured raw human feeling, emphasizing the unique character, inner turmoil, and often the vulnerability of their subjects. They used bolder brushwork, dramatic lighting, and richer colors to convey intense psychological states. Goya, in particular, delved into psychological shadows and moral complexities, creating portraits that were less about public image and more about searing, unflinching truth – an introspection I find endlessly compelling, much like trying to find the emotional core in a vibrant, chaotic abstract piece of my own. How do these contrasting ideals of civic virtue and raw emotion continue to influence how we portray ourselves today, especially in an age of curated online identities and social expectations, where we constantly balance projecting an ideal self with sharing raw, authentic moments?

The 19th Century: Capturing the Fleeting Moment and Inner World

The 19th century brought radical changes, perhaps none more impactful than the advent of photography in the 1830s. Suddenly, capturing a likeness became accessible and affordable for the masses, posing an existential challenge to painters. This democratization of imagery, however, paradoxically liberated painters, pushing them to explore what photography, in its nascent form, couldn't easily do: capture the subjective experience, the ephemeral impression, and the inner world. Painters responded by moving beyond mere mimetic representation, focusing instead on color, emotion, and eventually abstraction, reclaiming their unique domain. Photography challenged the very definition of 'art' itself, forcing painters to move beyond mere mimetic representation and delve into interpretation, emotion, and the abstract. It also enabled the widespread creation of caricatures, quick, often exaggerated portraits that satirized public figures and social mores, offering a new, critical lens on identity and challenging established norms with humor.

This push led to Impressionism, where artists like Édouard Manet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Edgar Degas, focused on capturing light, color, and the fleeting moments of modern life. Their portraits were less about grand narratives and more about an instantaneous feeling, a glimpse of personality in a casual setting. Think of Degas’s ballet dancers, caught mid-movement, or Renoir's joyful, sun-dappled figures. They used loose brushwork and vibrant palettes to convey the immediate visual sensation, often depicting scenes of leisure and urban modernity. Their focus on capturing light, color, and the fleeting moments of modern life, using loose brushwork and vibrant palettes to convey immediate visual sensation, resonates deeply with my own exploration of color to evoke emotion and atmosphere. It was a revolutionary way of seeing and representing the individual, often highlighting the changing social structures and the rise of leisure time.

![]()

Then, Post-Impressionists like Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin took this exploration of subjectivity even further, using color and brushwork to express intense inner emotion and symbolic meaning rather than merely objective reality. Van Gogh's self-portraits, for instance, are raw, intense explorations of his own psyche, a visual diary of his tumultuous spirit and personal mythology, elevating self-portraiture to a vehicle for psychological confession. Van Gogh's self-portraits, raw and intense explorations of his own psyche, are a visual diary of his tumultuous spirit – a powerful example of how art can serve as a vehicle for profound psychological confession, a principle I embrace in my own abstract expressions. This period also saw the rise of artists like the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in England, whose detailed, narrative portraits, imbued with symbolism and literary references, sought to return to the rich psychological depth and vibrant colors of early Renaissance art, offering a counter-narrative to academic painting. As technology advanced and society modernized, how did artists continue to adapt and redefine the very purpose of portraiture, moving towards increasingly abstract expressions of self, and challenging preconceived notions of beauty and reality, paving the way for the explosions of the 20th century?

The 20th Century and Beyond: Shattering and Redefining the Self

The 20th century saw portraiture fractured, reassembled, and dramatically redefined. Modernism challenged traditional representation entirely, pushing beyond mere likeness to explore deeper psychological and conceptual truths.

Cubism: Fracturing Reality

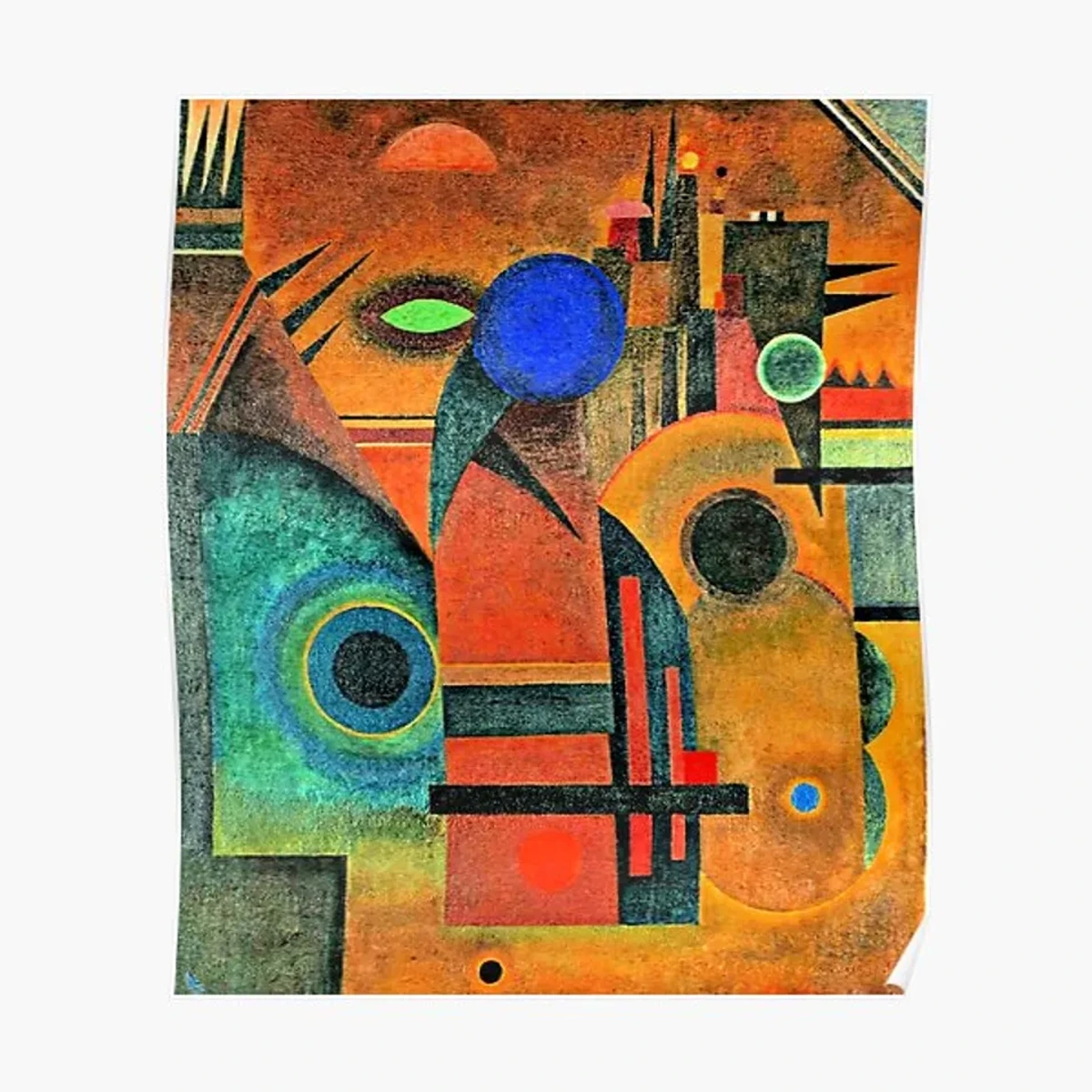

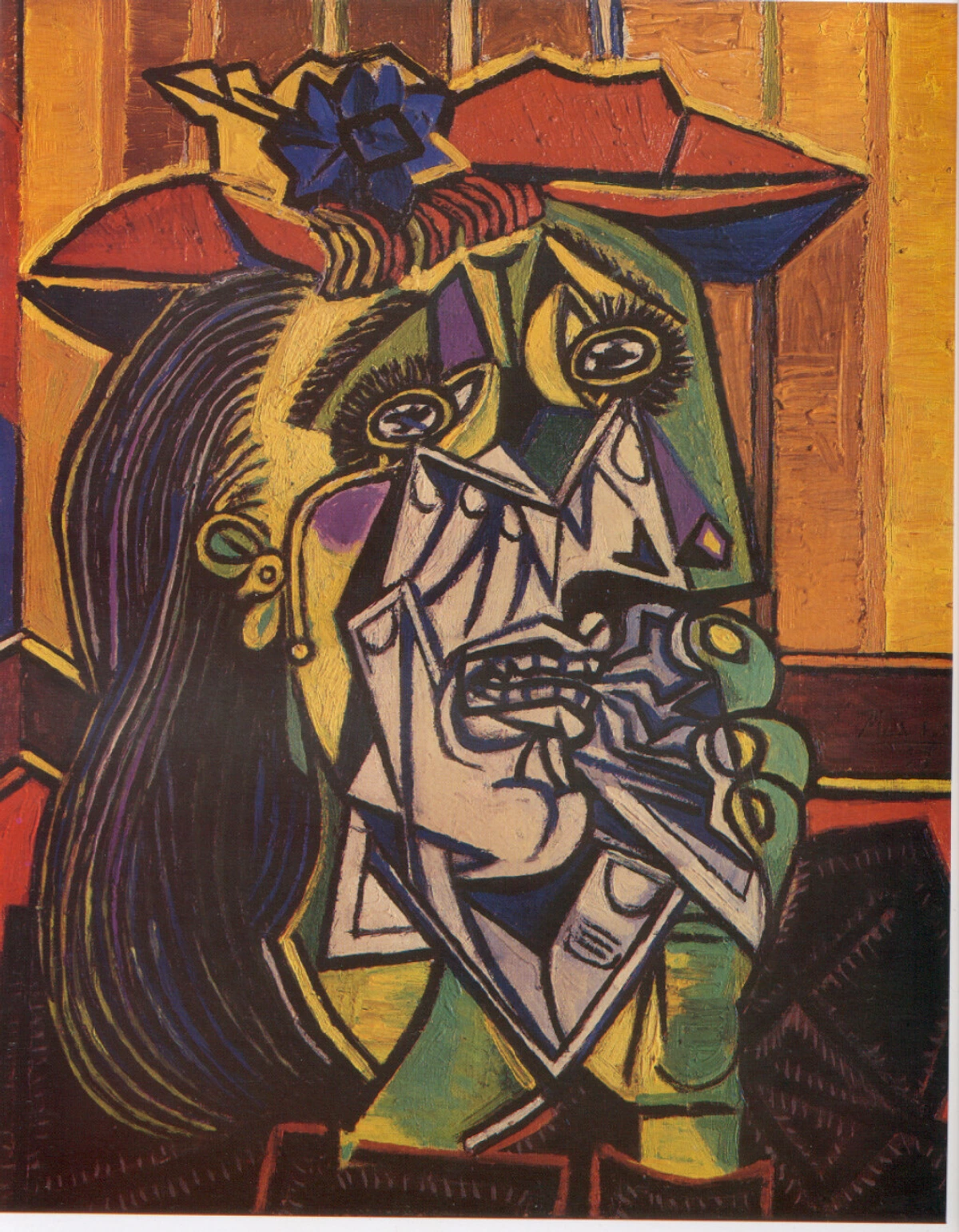

Cubism, pioneered by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, broke subjects into geometric forms, showing multiple viewpoints simultaneously. It wasn't about what a person looked like, but how they could be perceived, exploring the inner complexity and the multi-faceted nature of identity. While not always conventional portraits, works like Picasso's 'The Old Guitarist' or 'Weeping Woman' powerfully explore fragmented perspectives and raw emotion, acting as potent visual representations of internal psychological states. The artists sought to capture the essence of a subject not just from one static viewpoint, but from multiple angles at once, reflecting the fragmented and complex experience of modern life and the subjective nature of perception. You can delve deeper into its depths in the ultimate guide to Cubism. This approach to breaking down and rebuilding emotions deeply resonates with my own contemporary works, where I often seek to convey a fragmented yet cohesive feeling.

Amplifying Inner Worlds: Fauvism, Expressionism, and Symbolism

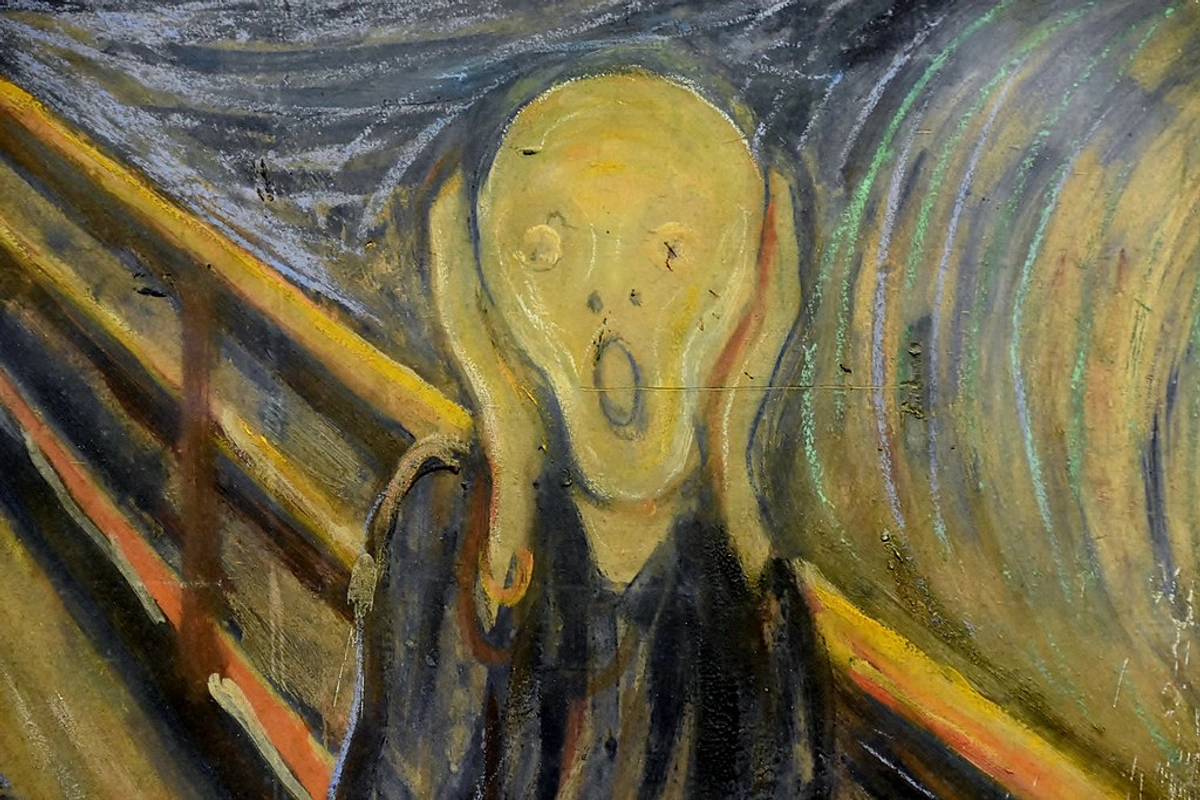

Fauvism, a precursor, saw artists like Henri Matisse use vibrant, often non-naturalistic colors to convey emotional impact rather than objective reality. While not always directly portraiture (e.g., 'The Red Room'), Fauvist principles of bold, expressive color laid the groundwork for a more subjective approach to depicting figures. This paved the way for Expressionism (e.g., Kees van Dongen, Edvard Munch, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner) which amplified emotion through distorted forms and vibrant colors, prioritizing subjective feeling over objective reality. This prioritization of subjective feeling over objective reality, using the portrait as a direct channel to the artist’s and subject's inner world, is a core tenet of my own artistic practice, where I aim to translate raw emotion into vibrant color and form. These artists aimed to evoke rather than merely describe, using the portrait as a direct channel to the artist’s and subject's inner world, often revealing profound psychological states or social anxieties. Munch's iconic 'The Scream,' while not a traditional portrait, powerfully captures an inner emotional landscape, making it a psychological portrait of anguish. Works by artists like Kees van Dongen, such as 'The Blue Dancer' or his expressive portraits, use bold, often clashing colors and simplified forms to convey the energy and mood of urban life, or the sitter's inner vitality, rather than just their physical appearance. You can delve deeper into this movement with the ultimate guide to Expressionism.

Symbolism, which overlapped with early Modernism, also contributed significantly to psychological portraiture, seeking to express profound ideas and emotions through symbolic forms rather than direct representation, delving into the mystical and the subconscious. It was about depicting the idea of a person or emotion. Then came Surrealism, with artists like Frida Kahlo, who explored the subconscious, dreams, and personal mythology, often through powerful and symbolic self-portraits that revealed profound psychological landscapes and challenged conventional narratives of gender and identity. Her work firmly established self-portraiture as a potent tool for personal and political expression, directly challenging societal norms through highly personal narratives.

Pop Art and Contemporary Approaches: Identity in a Mass-Media Age

Later, Pop Art (think Andy Warhol's iconic silk-screened celebrity portraits) blurred the lines between high art and popular culture, heavily influenced by mass media and advertising. It questioned notions of fame, mass production, and identity in a consumer society. Warhol’s signature silk-screening technique, by allowing for mechanical reproduction and slight variations, explicitly critiqued the commodification of celebrity, turning public figures into repeatable, almost anonymous, icons, effectively creating portraits that highlighted the superficiality of mass-media identity. Warhol's critique of mass production and the commodification of celebrity through his silk-screened portraits offers a prescient commentary on our current age of curated online identities and the blurring lines between authenticity and manufactured personas.

In contemporary art, portraiture continues to explode in new directions, often pushing against historical conventions. Artists use everything from traditional paint and sculpture to digital media, performance, and conceptual approaches. The rise of self-portraiture in the digital age, often shared online, reflects an ongoing, sometimes narcissistic, yet endlessly fascinating exploration of identity and 'digital identity' – how we present ourselves in virtual spaces. Contemporary artists often explore identity politics, the fragmented self, the portrait of a community rather than an individual, or even what it means to be human in an increasingly technological world. Artists like Jean-Michel Basquiat (whose vibrant, raw skull paintings challenge conventional beauty and representation, and whose life and work you can explore in the ultimate guide to Jean-Michel Basquiat) use the 'face' as a canvas for broader social commentary, often incorporating found objects and mixed media to challenge societal norms and represent marginalized voices. Basquiat's use of the 'face' as a canvas for broader social commentary, incorporating found objects and mixed media to challenge societal norms, mirrors my own approach of using abstract forms to convey complex ideas and represent marginalized voices or overlooked emotions. Other contemporary artists engage with the idea of the portrait as an act of resistance, giving visibility to those historically excluded from art history, or using new techniques like AI-generated portraits to question authorship and authenticity, exploring the boundaries of human creativity. These new mediums and approaches continuously challenge what a portrait can be, often blurring the lines between artist, subject, and viewer.

Ethical Considerations and the Evolving Role of the Portrait

Beyond aesthetics, portraiture has always touched upon profound ethical dimensions. The politics of representation – who gets portrayed, how they are depicted, and by whom – has shaped narratives and power dynamics throughout history, often reinforcing or subtly challenging societal stereotypes. From ancient pharaohs commissioning idealized images to modern movements giving voice to the voiceless, the power of who controls the image is immense. Issues of consent, particularly with vulnerable subjects, and the commodification of identity, especially with celebrity culture and mass media, continuously challenge its practice. For contemporary artists working on commission, the relationship with the client often involves navigating personal vision versus client expectations, a delicate dance of interpretation and collaboration.

In our current world, saturated with images and increasingly influenced by AI-generated portraits and deepfakes, discerning authenticity and intent becomes an even more crucial and complex part of engaging with portraiture. These technologies raise profound questions about misinformation, the erosion of trust in visual evidence, and the potential for manipulation that blurs the lines between reality and fiction. It forces us to ask: What happens when a 'face' can be conjured from code, completely untethered from a real person? Who owns that image, what does it mean for our understanding of identity itself, and how does this digital identity reflect back on our physical selves? As an abstract artist, even without depicting literal faces, I grapple with these questions of representation and meaning. How can I, through vibrant colors and forms, still convey a sense of 'presence' or evoke a universal human emotion responsibly, ensuring that the 'spirit' of my work honors a deeper truth rather than a superficial likeness or a manipulated image? It's a constant quest for genuine connection in a world overflowing with curated images.

Key Art Movements in Portraiture: A Summary

Era/Movement | Key Characteristics (Portraiture Focus) | Key Concept/Theme | Prominent Artist Examples | Materials/Techniques (Key) | Key Questions Explored |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ancient | Spiritual essence, eternal life, status, idealized forms; later, realism and civic power. | Immortality & Authority | Egyptian Pharaohs (sculpture), Roman Emperors (busts), Socrates | Stone, fresco, bronze | How to ensure eternal presence? How to assert power and lineage? |

| Renaissance | Individualism, humanism, psychological depth, status, piety, self-fashioning. | Individual & Legacy | Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, Titian | Oil on canvas/wood, fresco, miniature | What is the true essence of an individual? How to solidify one's place? |

| Baroque | Drama, emotion, grandeur, psychological introspection, self-portraiture. | Emotion & Power | Rembrandt van Rijn, Peter Paul Rubens | Oil on canvas (chiaroscuro) | How to express profound human emotion? How to project absolute power? |

| Rococo | Lightness, intimacy, aristocratic leisure, charm, subtle flirtation. | Grace & Pleasure | Jean-Honoré Fragonard, François Boucher | Oil on canvas (pastels, soft) | How to capture fleeting beauty and intimate moments? |

| Neoclassicism | Civic virtue, heroism, order, clarity, idealization; often propaganda. | Reason & Idealism | Jacques-Louis David | Oil on canvas (clear lines) | What defines an ideal citizen? How to inspire virtue? |

| Romanticism | Emotion, individualism, inner turmoil, vulnerability, subjective truth. | Passion & Individuality | Francisco Goya, Eugène Delacroix | Oil on canvas (expressive) | How to reveal the raw human experience? |

| 19th Century | Fleeting moments, light/color, social observation (Impressionism); subjective emotion, symbolism (Post-Imp.). | Perception & Inner World | Monet, Renoir, Degas, Van Gogh, Gauguin | Oil on canvas, photography | How to capture the instantaneous? How to reveal inner life? |

| 20th Century | Fractured reality (Cubism), amplified emotion (Expressionism), subconscious (Surrealism), mass media (Pop Art). | Subjectivity & Critique | Picasso, Matisse, Munch, Frida Kahlo, Andy Warhol, Basquiat | Oil on canvas, mixed media | How to portray the complex, fragmented self? How does media shape identity? |

| Contemporary | Identity politics, fragmented self, digital identity, community, AI, performance. | Plurality & Evolution | Jean-Michel Basquiat, AI artists, digital artists, performance artists | Digital media, mixed media | Who gets seen? What is authentic identity in a digital age? |

Why Do We Keep Gazing? The Enduring Power of Portraiture

From the eternal repose of an Egyptian pharaoh to the shattered planes of a Cubist face, and all the way to a hyper-realistic digitally rendered avatar, portraiture remains a fundamental human endeavor. It reflects our innate desire to see ourselves, to understand others, and to leave a lasting mark. It's a profound, evolving conversation not just between artist and subject, but crucially, also with the viewer, whose interpretation often completes and redefines the portrait’s meaning across time and culture. As an artist, I often find myself wondering how much of a portrait’s power truly lies in the original intent, and how much is breathed into it by each new pair of eyes that gaze upon it. The power of a portrait isn't static; it shifts with each gaze, each context, each new generation asking, 'What does this face tell me about myself and the world around me?'

For me, the essence of portraiture, even in its most abstract and non-representational forms, boils down to that connection – that quiet wonder about another's story, their hidden depths, what truly makes them them. It's why I find myself not just drawing literal faces, but ceaselessly trying to capture emotions, presences, and the echoes of souls in my own vibrant abstract art, often seeking that moment of recognition or resonance that transcends superficial appearance. This continuous search, this grappling with the invisible made visible, is what drives my artistic journey, a journey you can explore in my artist timeline or see firsthand at my museum in 's-Hertogenbosch. Sometimes, in my studio, I'll spend hours on a single color, trying to imbue it with a certain emotional weight, a feeling that a viewer might connect with on a primal level – not unlike how a Renaissance master would agonize over a subject's expression.

Portraiture, ultimately, is a mirror held up to humanity, showing us not just who we were, but who we are, and perhaps, who we aspire to be. And in this freedom to explore, to bend and break conventions – sometimes it's just about getting the nose right, and then deciding, 'You know what? Let's make it purple!' – lies its enduring, anarchic power to reveal deeper truths. After all, isn't art, at its best, about breaking the rules, or at least bending them into fascinating new shapes that reveal a deeper truth? I believe it is. You can explore how artists interpret different aspects of identity, such as body language in portrait art or discover my current explorations in abstract expression through my available works. What new truths will portraiture reveal to you today?