Rodin's The Thinker: The Ultimate Guide to its Profound Meaning, History, and Global Legacy

Uncover Rodin's The Thinker: from its origins in Dante's Inferno to its enduring symbolism of human thought and existential struggle. This ultimate guide explores its meaning, history, artistic technique, global impact, and timeless relevance, inviting deep introspection.

Rodin's The Thinker: The Ultimate Guide to Its Profound Meaning, History, and Global Legacy

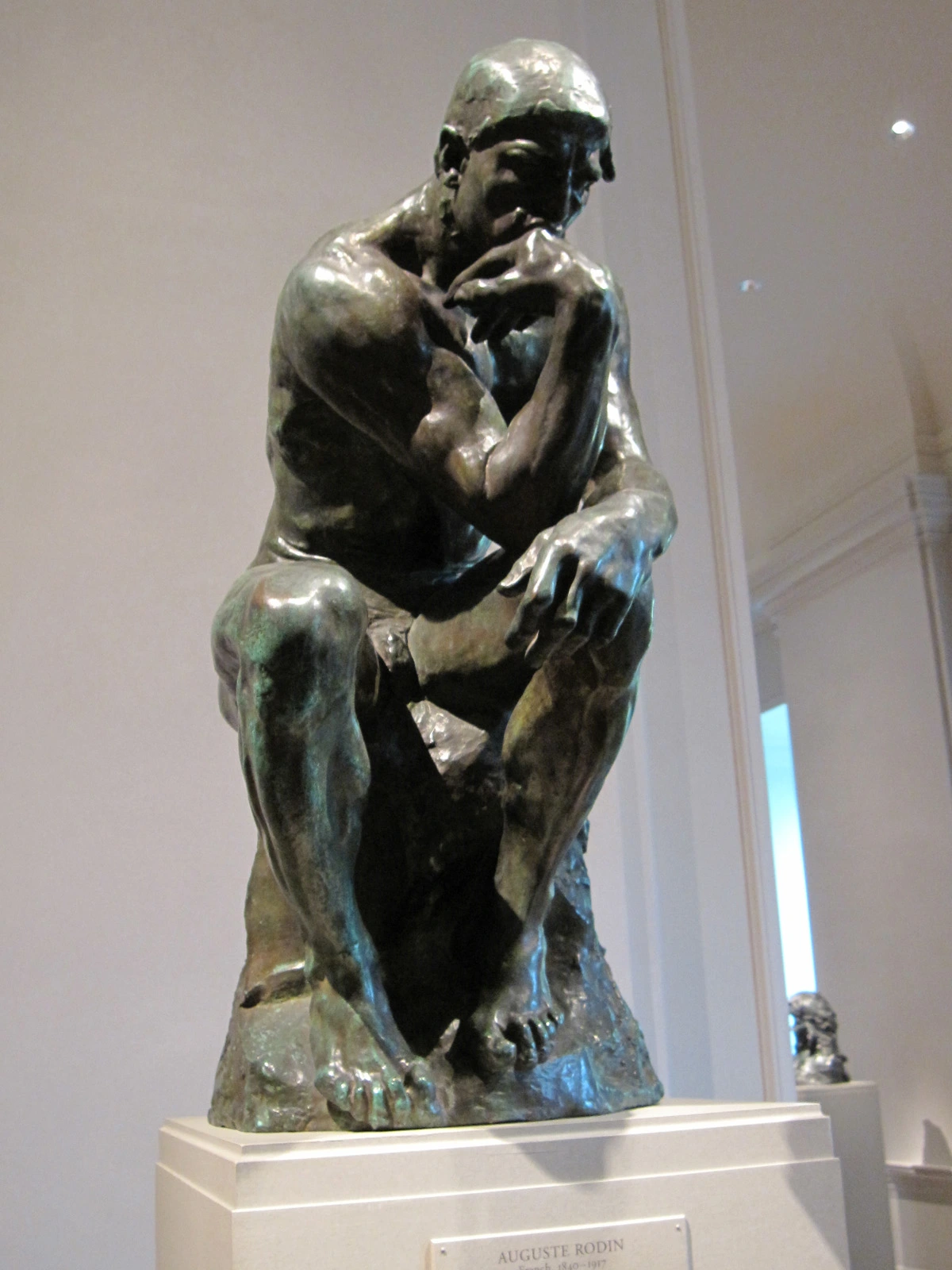

When I first encountered Rodin's The Thinker, probably through a somewhat blurry image in a hefty art history book, I'll confess my initial thought didn't stray much beyond, "Oh, that famous guy sitting there, looking pensive." I remember thinking: surely it's just a dude thinking, what's the big deal? Its ubiquity, through endless reproduction in everything from academic texts to pop culture memes, often risks diluting its true power into a visual cliché. But every single time I stand before one of the monumental bronze casts in person – and believe me, they are everywhere, like a philosophical marathon runner who never stops for a breath! – it’s an entirely different experience. There's this undeniable, palpable weight to it, a profound silence that somehow speaks volumes, an almost visceral sense of struggle and immense intellectual effort. It makes you, well, think. And I believe, with every fiber of my being, that this profound introspection is precisely the point, a silent roar of the mind.

This isn't just about a guy contemplating his grocery list, or even what to have for dinner (though I often grapple with similar weighty decisions, like whether to tackle the overflowing laundry basket or just buy new socks!). This is about humanity's core: the strenuous effort to understand, the painful birth of ideas, and the sheer, often agonizing, work of introspection. It's a masterpiece that, for me, transcends the physical limitations of bronze, inviting us into a universal dialogue about what it means to be human, to grapple with existence itself. My own abstract art often emerges from a similar place of deep contemplation, albeit perhaps less overtly anguished or monumental in scale! This guide will delve into the profound meaning, fascinating history, and enduring global legacy of Rodin's masterpiece, offering a definitive resource for understanding this iconic sculpture.

The Genius Behind the Bronze: Auguste Rodin's Revolutionary Vision

Before we delve into the sculpture's deep meaning, it's essential to understand the revolutionary artist behind it. Let's quickly touch on the man who brought him to life: Auguste Rodin. Born in 1840 in Paris, Rodin was a titan of sculpture, a true pioneer who bravely bridged the gap between traditional academic forms and the burgeoning expressions of modern art. His path wasn't always smooth sailing, and honestly, that's incredibly comforting for a struggling artist like myself. He was famously denied entry to the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts three times. Instead, he trained at the Petite École (École Impériale Spéciale de Dessin et de Mathématiques), where he focused on decorative arts, learning practical skills like ornament design and drawing. Later, he honed his craft working for established sculptors in Brussels, observing and refining his technique, often under masters like Albert-Ernest Carrier-Belleuse.

It was during these formative years, and particularly after a pivotal trip to Italy where he immersed himself in the works of masters like Michelangelo, Donatello, and even the dynamic Baroque forms of Bernini, that his unique vision began to solidify. I'm talking about the raw power of Michelangelo's David or the intensity of his Dying Slave, the deeply humanistic David and St. John the Baptist by Donatello, or Bernini's dramatic Ecstasy of Saint Teresa—these weren't just pretty figures; they embodied profound internal states and emotional narratives. Rodin, much like these masters, became obsessed with the human body, not merely for its physical beauty, but for its incredible power to convey emotion, movement, and profound psychological depth. His work, in many ways, was a precursor to the emotional intensity we'd later see in movements like Expressionism. As he once put it, he believed the human body was a "mirror of the soul." He didn't just sculpt bodies; he sculpted souls, making the invisible struggles of the mind visible, tangibly rendering the internal into the external.

A Rebel's Spirit: Challenging Academic Tradition

It's crucial to understand that Rodin's intense, often roughly textured, and emotionally charged style was not always universally embraced. During his lifetime, his departure from the smooth, idealized, and classically polished forms of academic sculpture was met with significant controversy and criticism. Sculptors adhering to academic norms, such as Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux or Antoine Mercié, prioritized idealized beauty, serene poses, and a finished surface that meticulously obscured the hand of the artist – a stark contrast to Rodin's raw truth. The Thinker, with its raw portrayal of mental anguish through physical form—its roughly textured surface, its contorted, internalizing pose, and its emphasis on psychological truth over classical perfection—was a bold statement against the prevailing artistic norms, particularly the Neoclassical ideal of tranquil beauty seen in works by Canova or even earlier academic masters. This very work solidified his reputation as a revolutionary artist who championed realism and emotional truth, paving the way for modern sculpture.

In stark contrast to the serene, polished nudes favored by the academies, Rodin's figures often showed the marks of their creation, their surfaces alive with the struggle of their subject. This wasn't merely a stylistic choice; it was a profound philosophical statement, suggesting that truth in art lay in the authentic portrayal of inner life, even if that life was messy, un-idealized, and visibly strained. This commitment to raw, unvarnished expression, I believe, is why his work still feels so incredibly relevant and powerful today, speaking directly to our messy human condition. His raw, dynamic handling of surfaces can also be seen in other works like The Burghers of Calais, where the varied textures amplify the figures' individual despair.

From the Gates of Hell: The Thinker's Dramatic Origins

Now, here's a crucial piece of the puzzle that often gets overlooked, and one that absolutely blew my mind when I first learned it. The Thinker (originally Le Penseur) wasn't conceived as a standalone sculpture at all. Imagine, if you will, the epic scale of his larger-than-life commission: The Gates of Hell. This monumental bronze doorway, commissioned in 1880 for a proposed Museum of Decorative Arts in Paris, was meant to be a grand entrance, echoing the magnificent portals of cathedrals, but filled with the tormented souls of Dante Alighieri's The Inferno. Picture the chaos, the despair, the swirling figures, the moral complexity of sin and redemption—it was an ambitious, almost impossible dream. (And, as it often goes with grand plans, the museum was never actually built due to funding issues and shifting political priorities, and the Gates remained largely unfinished during Rodin's lifetime – a classic artist's tale of an unfulfilled commission!).

Dante as the Original Thinker

Out of that unfulfilled architectural dream came some of Rodin's most iconic figures, with The Thinker being the most famous among them. Originally, this figure perched above the central panel of the Gates, looking down upon the tormented souls below. He was Dante himself, or perhaps a representation of the poet, contemplating the immense suffering and moral complexities of his own creation, wrestling with the profound narrative of damnation and salvation that The Inferno so vividly depicts. This context is vital because it immediately shifts our perception from a generic thinker to someone wrestling with profound, perhaps even agonizing, intellectual and emotional weight, an a priori struggle for understanding the human condition and the moral burden of depicting it. It reminds me a bit of the intense focus in Rembrandt's 'Faust,' but in three dimensions.

From Narrative to Universal Symbol

Rodin, ever the astute observer of the human condition, soon recognized the figure's power beyond its narrative confines. Around 1888, he began exhibiting it independently, first in a smaller version, then in monumental scale. It was then that Le Penseur truly took on a life of its own, its meaning expanding, deepening, and becoming universal. The public's enthusiastic reception affirmed its resonance as a symbol for all humanity's intellectual struggles – a defiant, muscular embodiment of thought itself. How did a figure born from the depths of Hell become such a universal emblem of enlightenment and profound contemplation? That, my friend, is the magic, isn't it? It speaks to something fundamental within us all.

Deconstructing the Contemplation: Layers of Meaning & Symbolism in The Thinker

So, if he started as Dante, what makes him The Thinker for everyone, across cultures and centuries? Well, it's in how Rodin masterfully captures an entire internal world through external form. Let's peel back those layers and see what universal truths are embedded in this bronze titan.

The Visceral Power of Human Thought: Embodied Cognition

At its core, The Thinker embodies human thought and creativity as an active, strenuous, and profoundly embodied endeavor. He's a powerful, muscular man, yet his power is focused intensely inward. His body, typically seen as a vessel for action, is instead coiled in supreme mental concentration. It's a physical manifestation of an intellectual act, a kind of internal explosion of thought, a silent, internal roar. This contrast is absolutely captivating, showing the incredible energy and tension required for true intellectual endeavor. Rodin masterfully uses the physical form to convey a purely mental state, suggesting that thought is not passive, but a vigorous, often strenuous, engagement.

This approach aligns beautifully with the philosophical concept of embodied cognition, which posits that our cognitive processes are deeply rooted in our physical experiences and bodily interactions with the world. Rodin's rendering of every taut muscle, every deeply etched line, makes the invisible activity and burden of the soul tangible, visible, and deeply felt. He makes the work of thinking visible, asserting that profound thought is a full-body experience.

The Agony of Introspection: Wrestling with Existence & Phenomenology

Look closely at his posture: the hunched back, the tightly clenched fist under his chin, the tension palpable in every limb, particularly his powerful hands and feet. This isn't a serene meditation, my friend. This is struggle. Rodin's genius lies in conveying that thought, especially deep, existential thought, isn't always peaceful. It can be painful, difficult, a wrestling match with ideas, emotions, and the crushing weight of consequence. His brow is furrowed, his lips pressed, every muscle in his powerful frame contributes to this depiction of an internal, agonizing battle. He's not just thinking; he's grappling with profound questions of life, death, morality, and human destiny.

This intense psychological drama reminds me of the raw emotion you find in works from the Romanticism movement, where intense personal feeling takes center stage. Philosophers of the era and beyond, grappling with the burden of knowledge and individual freedom, like Kierkegaard or even early Nietzsche, find a visual echo in this agonizing figure. It’s a physical embodiment of the burden of consciousness, a tangible representation of our individual and collective wrestling with what it means to simply be, to confront the vastness of existence. This resonates deeply with phenomenology, a philosophical approach that studies conscious experience as experienced from the subjective, first-person point of view, emphasizing the lived experience of being in the world.

The Raw Nude Form: Beyond Idealization

Rodin chose to depict him nude, much like many classical Greek and Renaissance sculptures. Think of the powerful, idealized figures of Donatello's David or Michelangelo's David. This wasn't for mere aesthetics; it was a deliberate choice to strip away any specific cultural, temporal, or social identifiers. This use of heroic nudity, echoing ancient Greek and Roman art, elevates the subject to a universal plane, embodying timeless human qualities and struggles. It elevates the intellectual effort to something primal and fundamental to the human condition, making his contemplation a pure, unadorned expression of humanity.

However, Rodin's nude is distinctly modern, a powerful contrast to the serene, effortless beauty of an antique Apollo or the smooth, finished surfaces of Neoclassical works by sculptors like Canova. While he referenced classical traditions, he deliberately subverted the classical quest for tranquil perfection by showcasing struggle and psychological truth rather than idealized beauty. His Thinker is less about an idealized form and more about the raw, unpolished effort of the mind—a nude that works and strains, embodying the theory of embodied cognition where mental states are inextricably linked to physical experience.

The Silent Pedestal: Symbolism of the Rock

Have you ever really considered the rock he sits upon? It's not just a perch. This rough, unadorned stone pedestal can be seen as symbolizing the raw earth, the primordial foundation from which human thought emerges – a grounding reality for even the most abstract or tumultuous internal worlds. Or perhaps it represents the immovable weight of existence itself, the unyielding burden of consciousness that The Thinker must shoulder. Its geological permanence can also contrast with the ephemeral nature of fleeting thoughts, literally and metaphorically anchoring him in the physical world even as his mind soars (or struggles) with the abstract. For Rodin, who was deeply interested in how thought manifests physically, this rock might represent the concrete reality that our most profound internal worlds are rooted in, making it a silent, stoic witness to his eternal internal drama.

Crafting Immortality: Rodin's Technique, Process, and Global Presence

It's truly fascinating how artworks evolve in meaning beyond their creator's initial intent. Rodin first imagined Dante, but the public saw something broader, something profoundly relatable. This, I think, is the true beauty of great art, isn't it? It becomes a mirror for the collective human experience, an echo across time that can even, for better or worse, become a meme, yet its foundational power remains untouched. This sculpture asks us to slow down, to engage our minds, and to recognize the value in deep, perhaps even uncomfortable, thought. In a world full of distractions, a bronze figure silently urging us to think feels more relevant than ever. Let's delve into how Rodin brought this enduring icon to life and how it spread across the globe.

Mastery in Material: The Art of Bronze Casting & Patina

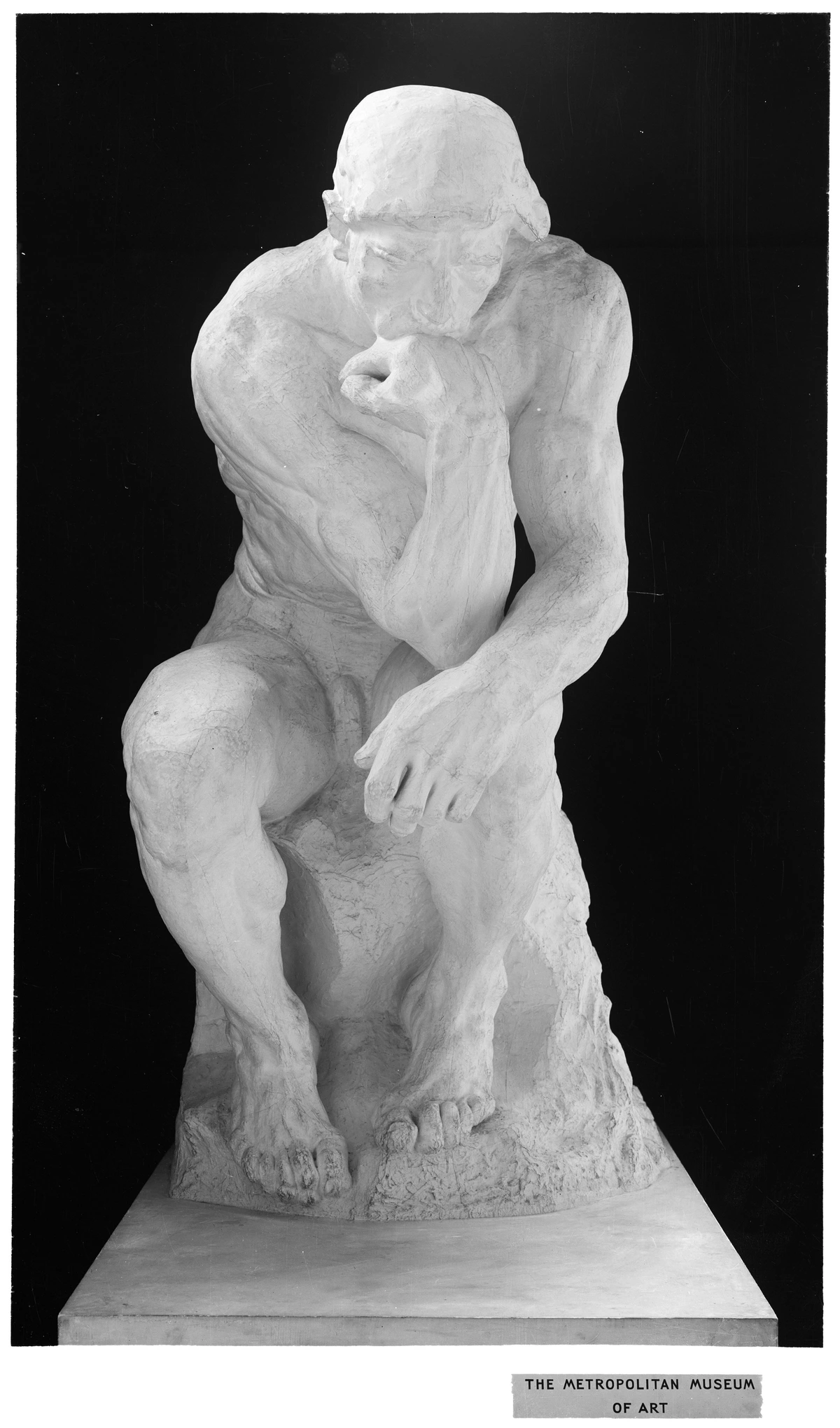

One of the reasons The Thinker is so iconic is Rodin's sheer mastery of materials. His approach to sculpture often involved creating multiple versions in various materials and sizes. He worked extensively in plaster and clay for his models, allowing him to refine forms before casting. For the monumental bronzes, Rodin primarily used the lost-wax casting method (cire perdue), a complex, multi-step process that allows for incredible detail and the reproduction of the nuanced textures of his original clay or plaster models. This technique, sometimes combined with sand casting for larger, simpler forms, was perfectly suited to capturing the rough, vibrant surfaces and expressive hand-marks Rodin desired, contrasting with the smooth, idealized finishes favored by academic sculptors. The internal armature (a supporting framework) would have been crucial for holding the initial clay and plaster forms in place during their creation and refinement.

These surfaces often retain the marks of his tools and his hands, adding to their raw, emotional power and a sense of immediacy, a direct connection to the artist's struggle and creation. The rich, dark patina (the surface finish achieved through chemical treatment) further enhances the sculpture's somber, powerful, and timeless presence, emphasizing its weight and solemnity. Patina isn't just a color; its primary purpose is to protect the bronze from corrosion, but it's also an integral part of the emotional landscape of the work. Different chemical mixtures (like sulfur compounds for reddish-browns, ammonium chloride for greens, or potassium polysulfide for dark browns/blacks) produce varied hues, each adding its own layer of narrative depth to the bronze, helping to make the invisible internal world of the Thinker visible to us.

Rodin's Vision to Bronze: The Creative Process

Rodin's meticulous creative process for The Thinker wasn't a single flash of inspiration, but a journey of refinement, much like an abstract idea slowly crystallizing into a concrete artwork. It began with numerous small sketches and maquettes (small study models, usually in clay or plaster) where he explored various poses and compositions. These initial studies, often dynamic and gestural, allowed him to capture the raw energy and fundamental gesture, experimenting with different angles and expressions until he found the perfect embodiment of intense thought, visible in the slight variations in early versions of the pose.

From these, he would develop larger plaster models, which served as the crucial intermediaries. Plaster models were valuable because they were durable enough for Rodin to work and rework the anatomy and expressive details with incredible precision, but also allowed for multiple casts to be made without damaging the original. These highly finished plaster models then became the basis for the final bronze casts. This multi-stage process, from fluid clay to durable bronze, highlights Rodin's dedication to capturing both the ephemeral nature of thought and the enduring power of human will. It's a testament to the idea that even the most profound ideas require significant effort and iteration to manifest – a lesson I often remind myself of in my own studio, particularly when a painting isn't quite clicking yet!

A World Tour of Thought: Monumental Casts & Global Locations

Rodin himself authorized numerous full-size and smaller versions, leading to approximately 28 monumental bronze casts of The Thinker around the world, in addition to many smaller plaster models, terracotta studies, and bronze reductions. Each is considered an authentic expression of the work, reflecting Rodin's innovative approach to serial production in sculpture. The first monumental bronze cast (completed in 1904) was initially placed in front of the Pantheon in Paris, a bold public gesture to encourage intellectual and social engagement. Later, in 1922, it moved to the serene gardens of the Musée Rodin in Paris, where it stands as a profound focal point within the artist's former home and studio, inviting quiet contemplation.

You can find other significant monumental casts, often slightly varying in patina or specific installation, in prestigious locations across the globe, each offering a unique dialogue with its environment:

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, USA: A central piece anchoring one of the world's most renowned modern sculpture collections.

- The National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Australia: Bringing Rodin's profound message to the Southern Hemisphere, offering a point of reflection in a bustling cultural hub.

- The Detroit Institute of Arts, Michigan, USA: A highlight of a historically significant American collection, often displayed outdoors, emphasizing its public accessibility and grand scale.

- The Legion of Honor, San Francisco, USA: Offering a contemplative moment with panoramic city views, blending classical art with nature and urbanity.

- The Kyoto National Museum, Kyoto, Japan: Bridging Western monumental sculpture with Japanese cultural heritage, symbolizing universal human inquiry and cross-cultural dialogue.

- The National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C., USA: A prominent feature in the nation's capital, inviting civic and intellectual contemplation from all who visit.

It's almost like he's on a perpetual world tour, inviting people everywhere to pause and reflect, a silent ambassador for introspection. The fact that Rodin's own museum, the Musée Rodin, is set in such a beautiful, contemplative space (the Hotel Biron) only adds to the mystique, a tranquil haven for profound thought. It's a testament to his global impact that his silent observer can be found pondering across continents, connecting humanity through shared introspection.

The Conservation of a Contemplative Giant

With so many monumental casts spread globally, the conservation and maintenance of The Thinker sculptures are ongoing efforts. Bronze, while durable, is susceptible to environmental factors like pollution, acid rain, and even bird droppings, which can accelerate corrosion and alter the patina. Beyond these, outdoor bronzes also face challenges like structural integrity issues over long periods for such large pieces, and sadly, the risk of vandalism. Regular cleaning, waxing, and periodic re-patination by skilled conservators are essential to preserve the integrity of the artwork and its intended visual and emotional impact. Each museum maintains a strict regimen, ensuring Rodin's vision continues to inspire for centuries to come, a silent testament to the lasting power of both art and diligent preservation.

My Artistic Dialogue: Rodin's Enduring Influence & Contextual Comparisons

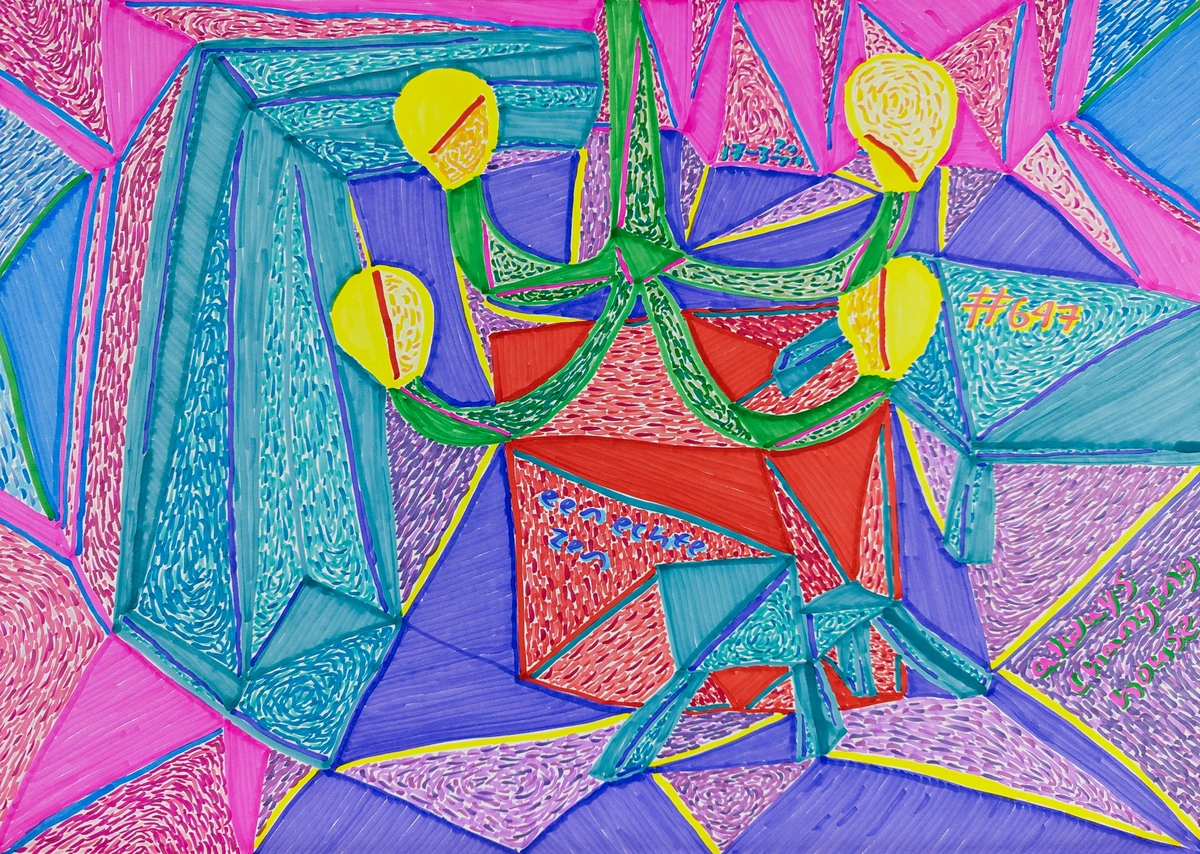

For me, as an artist, The Thinker is a powerful reminder that the process of creation, of truly engaging with an idea, is often as significant as the finished product. My own abstract art is often born from a similar place of deep contemplation, though perhaps less overtly anguished! For example, in my 'Shattered Realities' series, I aim to distill the confusion and eventual clarity of grappling with complex ideas into geometric forms and vibrant, clashing colors. It's about taking the unseen, the internal, and making it tangible through the physical act of painting. Rodin's sculpture embodies that universal struggle to translate the invisible world of the mind into something concrete. He shows us that even in moments of seeming stillness, there can be incredible energy and movement beneath the surface – a silent, internal roar of thought. Much like the quiet intensity of Agnes Martin's grids, where subtle variations in line and texture create immense internal resonance, The Thinker's motionless pose vibrates with internal activity, each muscle in Rodin's figure, like each line and repetition in Martin's work, contributing to a profound, almost spiritual internal rhythm.

Dialogues Across Time: Rodin in Artistic Context

It's always fascinating to see how artists tackle similar themes or forms across different eras and movements. Rodin's approach to sculpture, while revolutionary for his time, also drew heavily from classical traditions and paved the way for future explorations of the human psyche in art. Here's my take on how he stands in relation to some other giants, exploring the human condition and internal states, which I've summarized in this table for clarity:

Artist | Era/Movement | Key Focus | Connection to The Thinker | Key Artistic Innovation/Element |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Auguste Rodin | Late 19th - Early 20th Century (Symbolism, Realism) | Capturing raw emotion, movement, and profound psychological depth in bronze and marble. | His definitive work on the agony and power of human thought and creative struggle, a universal symbol of introspection. | Revolutionary Realism; capturing inner life through physical form. |

| Donatello | Early Renaissance | Reviving classical forms, emotional realism, individual expression through sculpture. | A master of expressive human form whose David and St. John the Baptist conveyed intense inner life and psychological depth, directly inspiring Rodin's use of the nude to convey universal truths through emotionally charged realism. | Emotional Realism; humanistic revival of classical forms, innovative use of linear perspective in relief. |

| Michelangelo | High Renaissance | Monumental scale, idealized human form, conveying spiritual and psychological states through powerful physiques. | His powerful, muscular nudes like David and the Sistine Chapel ceiling figures depict physical prowess mirroring inner strength and divine inspiration through dynamic contrapposto and anatomical exaggeration, a lineage Rodin powerfully continued, albeit with a raw, modern sensibility and focus on human struggle rather than divine perfection. | Monumental Idealism; expressing spiritual force through human physique and dynamic composition. |

| Caspar David Friedrich | Romanticism | Sublime landscapes, figures contemplating nature, themes of introspection, solitude, and profound emotion. | While a painter, his Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog or Two Men Contemplating the Moon echoes the pensive, introspective mood and engagement with profound questions found in The Thinker, albeit through different subjects and mediums, both creating a sense of awe and internal reflection in the face of the vast. | Sublime Introspection; solitary figures confronting vast nature, emphasizing spiritual experience. |

| Edgar Degas | Impressionism, Realism | Capturing fleeting moments of movement and human activity, often focusing on dancers and everyday life. | Degas' sculptures, like his dancers, capture intense focus and physical tension within a concentrated action required for performance, reflecting a different kind of internal discipline and dedication, albeit in dynamic motion rather than stillness, yet both artists sought truth in observing the body's expressive capacity. | Dynamic Naturalism; capturing fleeting moments and concentrated action, often in everyday life. |

| Francis Bacon | Post-War, Expressionism | Distorted, raw, and often violent portrayal of the human figure, exploring angst, existential dread, and psychological torment. | Offers a stark, visceral contrast, showing a later, more anguished exploration of the human psyche and internal suffering that resonates with the 'struggle' aspect of The Thinker, pushing Rodin's emotional intensity to new extremes of distortion and isolation. | Visceral Angst; distorted figures expressing psychological torment and the fragility of the human form. |

| Edvard Munch | Symbolism, Expressionism | Exploring themes of love, fear, death, and existential angst through powerful, often distorted figures and vibrant colors. | While depicting more overt agony and psychological screams in works like The Scream, Munch's focus on internal turmoil and the human psyche offers a compelling parallel to The Thinker's intellectual struggle, highlighting shared themes of suffering and profound human experience, though Munch often externalized this anguish more dramatically. | Emotional Intensification; symbolic representation of inner torment and human isolation. |

| Marcel Duchamp | Dada, Conceptual Art | Challenging art conventions, using readymades, prioritizing intellectual concepts over traditional craftsmanship. | A playful, yet profound contrast: Duchamp's Fountain asks us to think about what art is, shifting the contemplation from the subject within the art to the art object itself and the viewer's interpretation, making the act of viewing itself an intellectual exercise and challenging the very definition of artistic 'thought'. | Conceptual Provocation; challenging art's definition and the viewer's role in creating meaning. |

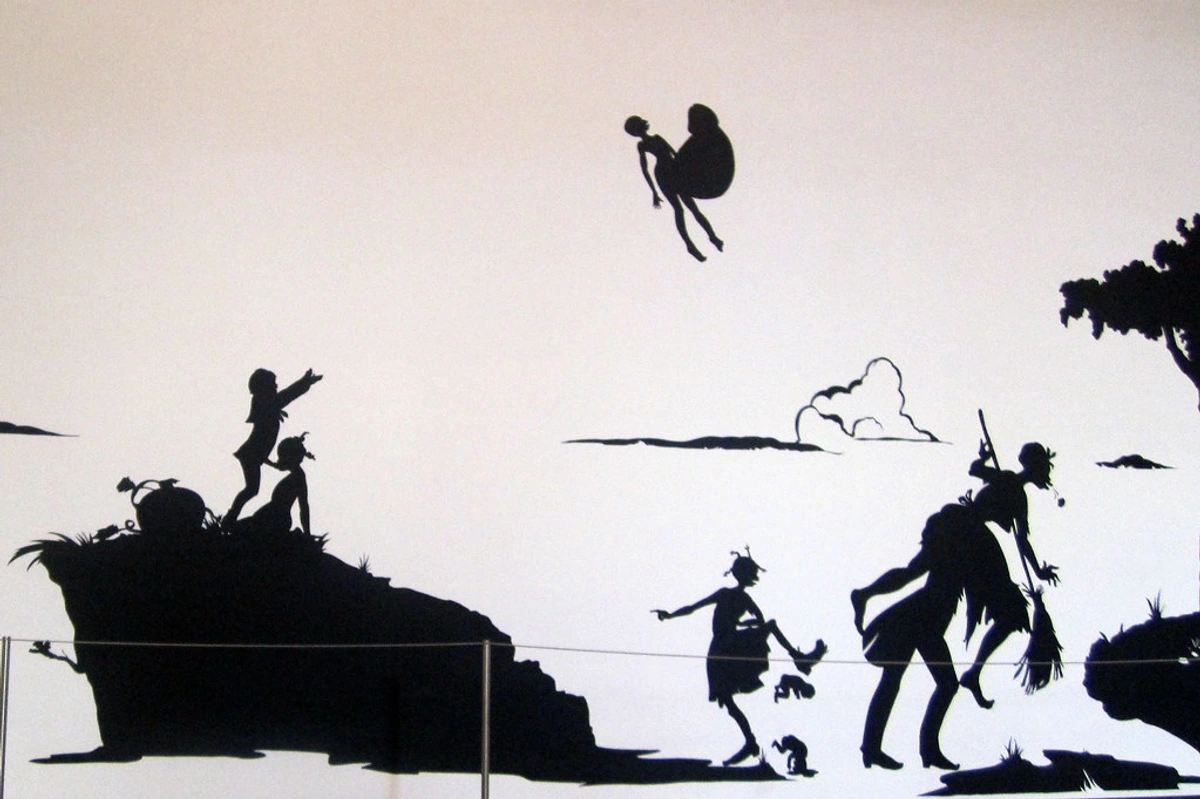

Cultural Reception and Modern Interpretations

Beyond the art world, The Thinker has permeated popular culture, appearing in countless advertisements, cartoons, and political commentary. Famously, the character Homer Simpson was depicted as The Thinker in a gag, highlighting how the image has become instantly recognizable as a shorthand for profound thought – or the humorous lack thereof. More seriously, its image has been used in political cartoons to symbolize public deliberation or a leader's profound (or lack of) strategic thought, and even as a motif in literature and film to represent intellectual struggle or artistic creation. This widespread recognition speaks to its enduring power as a symbol of intellectual pursuit, even if sometimes used humorously or ironically. In a way, these modern reinterpretations, whether reverent or irreverent, only solidify its status as a universal icon. It demonstrates that the core act of contemplation, of grappling with ideas, remains a fundamental and relatable human activity, adaptable to diverse cultural narratives and contemporary issues.

Other Contemplative Works by Rodin

While The Thinker is undoubtedly his most famous work of introspection, Rodin explored similar themes of human emotion and physicality throughout his career. Pieces like The Kiss (1882), which portrays intense passion and idealized love through a deeply entwined, yet emotionally complex, embrace, or The Burghers of Calais (1889), a powerful group sculpture depicting individual sacrifice, despair, and civic anguish in the face of death, showcase his mastery in conveying profound internal states through monumental bronze. Even many of the individual figures destined for The Gates of Hell – like Ugolino and His Children (exploring starvation and moral horror) or The Three Shades (depicting endless despair and resignation) – are deeply contemplative, reflecting on suffering, regret, and the human condition. The Thinker stands as the zenith of this lifelong exploration, a singular, powerful embodiment of the mind's internal theater.

Key Dates and Milestones in The Thinker's Journey

To provide a clearer chronological overview of this enduring masterpiece, here are some key dates and milestones in The Thinker's creation and reception:

Year | Event/Milestone | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| 1880 | Commissioned for The Gates of Hell | Rodin receives the commission for the monumental doorway inspired by Dante's Inferno, for which The Thinker was originally conceived as a figure representing Dante. |

| c. 1881-1882 | First small plaster model created | Rodin creates the initial 70cm plaster model, capturing the fundamental pose and intense focus. |

| c. 1888 | First independent exhibition | Le Penseur begins to be exhibited as a standalone work, signaling Rodin's recognition of its universal appeal beyond the Gates. |

| 1904 | First monumental bronze cast completed | The first life-size bronze cast is made, solidifying its presence as a monumental sculpture in its own right. |

| 1904-1922 | Installed in front of the Pantheon, Paris | The monumental cast is placed in a prominent public space, fostering civic and intellectual engagement. |

| 1922 | Moved to Musée Rodin, Paris | The iconic first monumental bronze finds its permanent home in the serene gardens of Rodin's former home and studio. |

| Ongoing | Numerous casts displayed worldwide | Approximately 28 monumental bronze casts are dispersed globally, cementing its status as a universal symbol of thought and introspection. |

Glossary of Key Terms

To enhance your understanding of the concepts discussed in this guide, here is a brief glossary of key terms:

Term | Definition in Context |

|---|---|

| Armature | An internal skeletal framework, typically made of metal wire or wood, used to support a sculpture (especially in clay or plaster) during its creation, preventing it from collapsing under its own weight. |

| Embodied Cognition | A theory in philosophy and cognitive science suggesting that our thoughts and cognitive processes are not purely abstract but are deeply influenced by our physical body's interactions with the world, including its sensations, movements, and environment. |

| Existentialism | A philosophical movement emphasizing individual existence, freedom, and responsibility. It suggests that individuals are responsible for creating meaning in a meaningless world, often leading to feelings of anguish, dread, and a profound wrestling with personal choice. |

| Lost-Wax Casting (Cire Perdue) | A complex, ancient metal casting technique where a duplicate metal sculpture (often bronze) is cast from an original sculpture. The process involves creating a wax model, encasing it in a mold, melting out the wax, and then pouring molten metal into the cavity. |

| Maquette | A small-scale model or sketch, typically in clay or plaster, made by a sculptor as a preliminary study for a larger work. It helps in exploring composition, form, and overall design. |

| Neoclassicism | An art movement (mid-18th to early 19th century) that drew inspiration from the classical art and culture of Ancient Greece and Rome, emphasizing order, symmetry, idealized forms, and a moralizing tone. It typically favored smooth, polished surfaces in sculpture. |

| Patina | The surface finish or coloration that develops on bronze or other metals over time due to natural aging or through artificial chemical treatment. It serves to protect the metal and contributes significantly to the aesthetic and emotional impact of a sculpture. |

| Phenomenology | A philosophical study of conscious experience as it is experienced from the subjective, first-person point of view. It focuses on the structures of consciousness and the phenomena that appear in acts of consciousness. |

| Sand Casting | A metal casting process that uses non-reusable sand molds to create metal parts. It's often used for larger, simpler bronze forms and can create a slightly rougher surface texture compared to lost-wax casting. |

| Symbolism | An art movement (late 19th century) that sought to express abstract ideas, emotions, and inner truths through symbolic imagery rather than literal representation. It often emphasized the mysterious, the spiritual, and the subjective. |

Frequently Asked Questions About The Thinker

To further illuminate the multifaceted nature of this iconic sculpture, let's address some frequently asked questions.

What is The Thinker trying to do?

Simply put, The Thinker is depicted in deep, intense contemplation. He's wrestling with profound thoughts, likely concerning the fate of the souls in Dante's Inferno (its original context) or, more broadly, the human condition, morality, and destiny. His physically tense posture, with his hunched back and clenched fist, vividly reflects this immense mental and emotional effort. It's an active, even agonizing, process of internal wrestling, not passive reflection, tapping into the a priori human capacity for profound thought. Rodin makes the work of thinking visible.

Is The Thinker meant to be a physical being experiencing thought, or a symbol of thought made physical?

I'd argue it's brilliantly both. Rodin's genius lies in creating a figure so physically robust and demonstrative of effort that it makes the invisible process of thought tangible. The muscular body emphasizes that profound intellectual work is not disembodied; it's a full-body experience, a demanding act of human will and being, aligning with philosophical embodiment theory and even phenomenology (the philosophical study of conscious experience as experienced from the subjective or first-person point of view). So, he's a physical being embodying the experience of thought, while simultaneously serving as a powerful, universal symbol of thought made manifest. He embodies both the individual struggle and the universal human capacity for deep reflection.

What is The Thinker made of?

The most famous and monumental versions of The Thinker are cast in bronze. Rodin also created numerous plaster models, terracotta studies, and marble carvings during the development of the work. The bronze versions are typically dark with a rich patina, which significantly contributes to their somber, powerful, and timeless presence. The rough, textured surfaces of the bronze often bear the marks of Rodin's tools, adding to their raw, expressive quality and showing the hand of the artist and the effort of creation.

How many versions and sizes of The Thinker exist?

There isn't a single definitive "original" in terms of size, as Rodin authorized multiple full-size and smaller versions throughout his lifetime and posthumously. There are approximately 28 monumental (life-size or larger) bronze casts of The Thinker around the world, in addition to many smaller plaster models, terracotta studies, and bronze reductions. Each of these is considered an authentic work authorized by Rodin's estate, showcasing the work's immense impact and demand. This multitude of versions underscores its widespread cultural significance, with each cast acting as a distinct "original" in its own right due to the artist's unique working method.

Where is the original The Thinker located?

This is a great question, but for Rodin's work, "original" is a complex term due to his multi-stage process and authorized reproductions. The very first small plaster model (around 70 cm high), which served as the initial study for the Gates of Hell, is housed at the Musée Rodin in Paris, France. The first monumental bronze cast (completed in 1904) was initially installed outside the Pantheon in Paris, but was later moved to the gardens of the Musée Rodin in 1922, where it remains a central and profoundly moving attraction today. So, both the first small study and the first monumental cast are proudly displayed at the Musée Rodin, making it the primary site to experience its profound legacy, though each authorized cast holds its own authenticity.

What are the typical dimensions of the monumental casts?

The monumental bronze casts of The Thinker are typically around 186 cm (73 inches) in height, 140 cm (55 inches) in width, and 185 cm (73 inches) in depth. This impressive scale significantly contributes to the sculpture's impactful presence, making the viewer feel truly in the presence of a titan of thought. It's not just a statue; it's an imposing, contemplative figure that looms large both physically and metaphorically, commanding attention and demanding reflection.

What inspired Rodin to create The Thinker?

Rodin was initially commissioned to create a monumental doorway, The Gates of Hell, inspired by Dante Alighieri's epic poem The Inferno. The Thinker was originally intended to represent Dante himself, observing the suffering in Hell and contemplating his poetic creation and the moral weight of humanity's choices. Over time, Rodin recognized the figure's universal appeal and gave it an independent existence, broadening its meaning to symbolize universal human thought, intellectual struggle, and the profound act of creation itself. Its roots in Dante's intense narrative gave it a foundational depth that allowed its meaning to expand globally, resonating with anyone who has grappled with weighty decisions or existential questions.

What is the overall message or purpose of The Thinker?

The overall message of The Thinker is to celebrate and monumentalize the act of human thought itself – particularly profound, strenuous, and often agonizing introspection. It serves as a universal symbol for philosophy, intellectual pursuit, and the struggle inherent in human consciousness and creativity. Rodin invites us to acknowledge the immense effort required for true understanding and the burden of knowledge, positioning thought not as a passive state, but as a dynamic and powerful force that shapes our humanity. This aligns with existential philosophical themes that emphasize individual responsibility and the weight of self-awareness in confronting the human condition.

The Unending Invitation to Think

So, the next time you see an image of Rodin's The Thinker, or better yet, stand before one of its bronze forms, don't just see a statue. See a mirror. See the universal struggle of the mind, the profound effort of creation, and the quiet, intense power of introspection. It's a testament to the enduring human capacity to grapple with the big questions, and a beautiful, timeless reminder that sometimes, the most powerful action is simply to think – to truly, deeply, and perhaps even agonizingly, reflect. In our hyper-connected, fast-paced world, The Thinker stands as a silent sentinel, urging us to slow down and engage with our inner lives, to find power in the quiet storm of our own minds.

I challenge you to pause, just like The Thinker, and dedicate a moment to deliberate contemplation today. Perhaps it will inspire you to delve into your own thoughts, to explore connections between art and philosophy, or even to create something new yourself, just as Rodin did. You can always check out some modern inspirations and artistic parallels at my Den Bosch Museum or explore my timeline of artistic influences, seeing how deeply artists throughout history have grappled with the invisible worlds within us. What insights might be waiting within your own mind, eager to be brought into tangible form?