What is Patina? Time's Artful Touch on Materials, Life & Art

Unravel the profound beauty of patina: how this natural surface change forms on metals, wood, stone, glass, and paintings, its deep science, immense value, and the ethical tightrope of preservation. Discover time's unique artistry and the stories objects whisper through age.

What is Patina? The Enduring Art of Time's Touch in Art & Life

I vividly recall a moment, quite some time ago, standing before an ancient bronze sculpture. My first, utterly unfiltered thought was, 'Someone really needs to clean that thing!' It had this peculiar greenish, almost dusty film over it, and my then-unrefined eye saw nothing but neglect, perhaps even a bit of grime. Beauty? Historical depth? Absolutely not on my radar. But little did I know, I was about to embark on a journey of profound re-alignment—a journey I hope to take you on today.

Then, a tiny, internal lightbulb flickered on. I stumbled upon the concept of patina, and honestly, my entire worldview (at least, my art-world view) shifted. It wasn't dirt. It was a testament, a badge of honor, a story etched by the relentless yet gentle hand of time itself onto the surface of that artwork. Suddenly, that 'dirty' sculpture became profoundly beautiful, a living testament to its long, arduous journey. It's truly fascinating how our perception can warp and re-align, isn't it? As an artist who pours so much energy into creating something new, vibrant, and immediate – a snapshot of the present moment, if you will – this shift wasn't just philosophical. It fundamentally reshaped how I approach my materials. I've found myself thinking about not just the initial burst of color or the fresh texture, but how each stroke, each layer, might contribute to a future 'patina' of the piece itself, accumulating depth and narrative over time. It taught me to see a different kind of beauty, a slow-motion narrative of endurance, and even how to deliberately explore textures for abstract paintings that hint at this layered history.

And that's precisely what this deep dive into patina aims to do for you: to unravel the complex beauty and profound significance of these natural surface changes across a myriad of materials – from the obvious metals and woods to the more surprising realm of paintings and textiles. This isn't just about understanding a technical term; it's about seeing the life of an object, much like the lines on an older person's face tell countless tales of laughter, worry, and wisdom. What initially appears as decay or imperfection can, with a slight shift in understanding, unveil itself as a sign of profound authenticity, enduring history, and a character so unique that no human hand could replicate it in a single lifetime. It's a journey into the art of time itself, and a beautiful reminder that change, when embraced, can be its own form of creation.

Patina Unveiled: Its Essence, Origins, and Types

So, let's peel back the layers – what is this mysterious, often revered patina? Simply put, and pronounced pah-TEE-nah, it refers to the surface changes that naturally occur on objects over extended periods. These changes are usually the result of aging, environmental exposure, or various chemical reactions. Think of it as a natural veneer, a thin, often stable and protective layer that forms on materials like metal, wood, or stone. It's not just some random discoloration; it's a deliberate, albeit slow, collaboration between the object and its environment, often culminating in a remarkable visual and tactile transformation.

This layer is often remarkably stable, protective, and yes, undeniably visually appealing. It can manifest as a deep, resonant luster on aged wood, a rich spectrum of green or blue-green on bronze, or a smooth, almost velvety darkened sheen on ancient artifacts. Each mark, each subtle shift in color or texture, is a quiet whisper from the past, an almost geological record of its existence, inviting you to run your fingers over its storied surface.

We often talk about two primary categories when it comes to how these remarkable transformations come about:

- Patina of Age: This refers to changes that primarily arise from the sheer passage of time and exposure to natural environmental factors. Think of the way outdoor bronze statues gradually acquire their beautiful green hue from centuries of interaction with oxygen and moisture, or how sunlight slowly deepens the color of an antique wooden chest. It's time working its quiet magic, an artist you can't rush.

- Patina of Use: This category highlights the impact of human interaction. It's the unique sheen that develops on a well-loved leather armchair from countless touches, the smoothed edges of an old door handle, or the darkened areas on a wooden tool from years of steady grip. It's the physical narrative of an object's life and the stories of all the hands that have cherished and worked with it. Of course, these two aren't mutually exclusive; often, the most cherished patinas are a beautiful blend of both time and human touch.

Patina vs. Tarnish: A Crucial Distinction

This is a nuanced but important distinction, and one that trips many people up! While both are forms of surface change, patina generally refers to a stable, often protective, and usually desirable layer that enhances an object's value and aesthetic (e.g., the rich green or brown on an old bronze statue or the deep luster on antique wood). Patina often integrates deeply into the material's surface, becoming part of its character, like the lines on a wise elder's face, adding to its story. It's considered an integral, often beneficial, part of the object's history, celebrated for its authenticity.

Tarnish, on the other hand, is typically a thinner, less stable layer of corrosion that forms on reactive metals like silver, brass, or copper (often appearing as a dulling, darkening, or blackening film). It is usually considered undesirable because it can obscure the original brilliance and intricate details of the object. While technically a form of oxidation and thus a type of surface change, tarnish is often more superficial and can even lead to more destructive corrosion if ignored. Think of the black film on old silverware – it’s a surface change, yes, but one that detracts from its intended function and beauty. For example, the dull blackening on a silver reliquary might obscure intricate engravings, whereas the vibrant green on a centuries-old Donatello bronze statue is cherished. In essence, desirable patina is celebrated; tarnish is usually rectified. It's the difference between a beautifully weathered face that tells a story and a superficial, obscuring stain – both are changes, but one enhances, the other detracts.

The Secret Life of Materials: How They Dance with Time and Elements

It’s less of a random event and more of a chemical dance, a slow, deliberate performance over years, sometimes centuries. Each material has its own unique way of collaborating with its environment to form these enduring surfaces.

Metals: A Chemical Ballet of Oxidation

For metals like bronze, copper, or brass, patina is most often the result of oxidation, where the metal reacts with oxygen, moisture, and other elements present in the atmosphere – even pollutants play a role! This interaction creates a host of new chemical compounds on the surface. For copper and bronze, we often see vibrant green malachite (copper carbonate) or brilliant blue azurite, forming an elegant, albeit gradual, chemical transformation. Other metals react differently:

- Iron: Develops a distinctive reddish-brown rust (iron oxides) which is generally destructive.

- Aluminum: Might form a very thin, invisible, but protective oxide layer, shielding the metal beneath without a visible color change.

- Silver: Forms a black silver sulfide (tarnish) in the presence of sulfur compounds.

- Lead: Can develop a soft, greyish-white lead carbonate layer.

It's crucial to distinguish between a stable, protective patina (like the bronze carbonates that shield the underlying metal) and active corrosion that eats away at the object itself. Destructive forms like active 'bronze disease' (a powdery, unstable corrosion often caused by chlorides) or the characteristic red rust on steel and iron (a form of oxidation compromising structural integrity) are unequivocally harmful, requiring intervention. My own understanding of these processes has really made me think about the inherent fragility of even the toughest materials, and how much care goes into preserving them.

Wood: The Grain's Silent Storyteller

On antique furniture, carvings, or architectural elements, wood patina is a beautiful tapestry woven from the accumulation of natural oils and waxes transferred from countless human hands (a wonderful example of patina of use), prolonged exposure to light (often darkening and enriching the grain), and the natural aging and oxidation of the wood itself. Oil-based finishes, like linseed or tung oil, interact particularly beautifully with UV light and air over decades, gradually deepening their hue and acquiring a gentle, rounded softness on edges from years of handling. Harder finishes like shellac or lacquer, while protective, tend to show more surface wear and craquelure, rather than the deep penetration of a true wood patina. The tannins and lignins in wood also play a crucial role, reacting with environmental factors to create unique color shifts. Different wood species develop distinct patinas – think of the rich, deep mahogany versus the honeyed glow of aged pine, or the subtle graying of weathered oak. It’s that warm, deep, almost glowing luster you see on pieces that have been cherished for generations. It tells you about quiet rooms, sunlit corners, and human touch, accumulating stories in its very grain. And sometimes, it even has a distinct, comforting scent – the subtle, sweet aroma of aged wood, a quiet testament to its history.

Stone: Nature's Patient Etching

Consider ancient statues, monuments, or venerable buildings. Here, patina isn't just one thing. It could be mineral deposits leaching out and staining the surface (e.g., calcium carbonate from hard water, or iron oxides creating reddish streaks, or the subtle darkening from manganese oxides), the gradual colonization by algae, lichens, or moss (which can etch intricate patterns into granite or marble and even excrete organic acids that slowly break down rock, subtly reshaping the surface over millennia), or simply the slow, relentless process of erosion and weathering that softens sharp edges and smooths surfaces over centuries. Acid rain, for instance, can interact with limestone, creating unique 'chalking' patterns. Imagine a marble statue, initially stark white, slowly gaining a subtle mossy green hue in its crevices, while exposed surfaces are smoothed by centuries of wind and rain. Think of the intricate, almost calligraphic patterns lichens etch onto old gravestones or the dark streaks of mineral runoff on the ancient pyramids. That delicate balance of biological and geological processes creates a unique, unrepeatable surface. I find it endlessly fascinating how nature gently reclaims and subtly redefines man-made objects, integrating them back into the natural world.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/vintage_illustration/51913390730, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/

Paintings: The Canvas's Slow Sigh of Time

While not a chemical layer in the traditional sense, old paintings undeniably develop their own unique 'patina.' Varnishes, applied to protect and enhance colors, inevitably yellow, amber, and often develop a fine network of cracks over time – known as craquelure. This yellowing is often due to the degradation of natural resins (like dammar or mastic) used in older varnishes, sometimes even involving the saponification of oil binders. Saponification, in this context, is when the oils in the paint layer react with metallic pigments (like lead white), creating a soap-like substance that can alter texture, translucency, and shift the entire color balance of the painting. Think of it like a slow, irreversible soap-making process happening right on your canvas.

Pigments themselves can subtly shift or fade. Historically, some organic reds (like madder lake or cochineal) and blues (like indigo) were known to be fugitive, losing their vibrancy with prolonged light exposure, dramatically altering the painting's original chromatic intent. Even the canvas or support itself can show signs of age, such as stretching marks, minor tears, or discoloration from environmental exposure. Historically, craquelure and the warm glow of aged varnish were often celebrated as signs of authenticity; some even tried to mimic craquelure! All these elements combined contribute to a painting's unique journey, adding a depth and visual history that a brand-new canvas simply doesn't possess. It’s like the painting is breathing its own slow, artistic sigh of time. When I look at the delicate web of craquelure on an old master's work, I'm reminded of the intricate textures I build into my own abstract pieces, each tiny crack or raised line telling a silent story of process and time.

Other Materials: Everyday Narratives of Age and Use

Beyond the more common materials, many everyday objects also develop a cherished patina, often telling very personal stories:

- Leather & Textiles: The rich, supple sheen on an old leather armchair, absorbing years of use and conditioning, or the distinct, darkened luster on a vintage doctor's bag from decades of handling, are classic examples of patina of use. For textiles, the gentle fading and softening of dyes and fibers from prolonged use and light exposure also constitutes a form of patina, speaking volumes about the life of a garment or tapestry.

- Paper: The subtle yellowing and softening of an antique book's pages, often due to lignin degradation and acidity, tells its own quiet story of time, sometimes accompanied by 'foxing' (brown spots from mold or iron impurities). Imagine the brittle, darkened edges of an antique map or the subtle loss of vibrancy in early photographic prints due to chemical degradation. My own old sketchbooks, filled with early ideas, are starting to show this beautiful wear, almost like a visual timeline of my artistic journey.

- Glass: Over centuries, especially in archaeological contexts, glass can develop a subtle iridescent sheen or a darkening tint due to glass sickness – a form of deterioration where alkalis leach from the glass, creating an unstable, layered surface that catches the light beautifully. Think of ancient Roman glass vessels unearthed with this ethereal rainbow shimmer.

- Ceramics: While typically more stable, ceramics can acquire patina through subtle glaze crazing (a network of fine cracks that develops in the glaze layer over time due to differing expansion rates between glaze and clay body), mineral deposits from water exposure, or the staining and subtle darkening from absorbed oils and use. An ancient Raku tea bowl, with its unique glaze and surface changes from repeated handling, perfectly embodies the wabi-sabi aesthetic of accepting imperfections. My hands often gravitate to the smooth, cool surface of an old, well-loved ceramic mug, feeling the subtle shifts in its texture that tell of countless cups of coffee.

- Photography: The delicate art of photography also experiences patina. Early photographic prints, such as albumen prints or daguerreotypes, are particularly susceptible to chemical changes. The silver compounds can react with atmospheric pollutants, leading to subtle yellowing, fading, or even a silvery sheen, creating a unique historical character that separates them from pristine, modern prints. This aging process adds an undeniable sense of history and fragility.

In each case, human interaction and simple environmental exposure contribute to a unique, cherished aesthetic.

The Invisible Hand: Science Behind the Sheen

At its heart, patina is a story of interaction – often on a molecular level. For metals, it’s primarily an electrochemical process: the metal surface gives up electrons (oxidation) in the presence of an electrolyte (like moisture in the air) and an oxidant (like oxygen). These new compounds form a stable layer that often adheres tightly, changing the surface's optical properties and forming the visible patina. It's nature's own subtle Instagram filter, applied gradually over centuries. But did you know that factors like humidity, temperature, and even the unique blend of pollutants in the air play a crucial role in accelerating or altering its formation? That's right, your local environment is actively collaborating with your art – it's like a secret co-artist you never commissioned! Coastal environments, for example, with their higher humidity and salt content, can significantly accelerate the patination of metals, often yielding unique finishes with distinct textures, sometimes roughened, sometimes smoothed. Urban environments, with higher concentrations of sulfur compounds, might produce darker, often less stable patinas on some metals. Even altitude, specific geological factors like volcanic ash, or persistent airborne particles can leave their unique mark, creating regional variations in patina that tell another layer of story. I find it endlessly fascinating how these invisible forces conspire to create visible beauty.

For stone, the science shifts. It can involve the slow dissolution and recrystallization of minerals, or perhaps the biological processes of microscopic life. Lichens, for example, can excrete organic acids that slowly break down rock, creating a superficial layer that is both protective and uniquely textured, subtly etching intricate patterns. Algae and mosses similarly contribute, creating vibrant green carpets in damp, shaded areas. It's a complex ballet of physics, chemistry, and even biology, all working in slow motion to create something truly unique. As renowned conservator Dr. Eleanor Vance once noted, "The patina is the object's autobiography, written in chemical reactions and biological growth." When I observe these slow, relentless processes, I'm reminded that even the most static materials possess an inherent drive to transform and interact, much like the dynamic interplay of elements and the deliberate layering in a vibrant abstract painting. This natural artistry serves as a profound inspiration, showing how subtle layers and unexpected reactions can create immense depth – a principle I constantly explore when creating textures for abstract paintings.

https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/53064827119_1b7c27cd96_b.jpg, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.0/

More Than Just Good Looks: The Enduring Value of Patina

Beyond its purely aesthetic appeal, which is considerable, patina holds immense historical, emotional, and even economic value. It’s far more than just surface color; it's a verifiable timestamp, an authentic mark of age that often speaks louder than any signature or date. When you encounter a well-developed patina on an antique, you don't just see it; you feel its history. You know it's been there. It hasn't merely been created; it has truly lived.

A Window to the Past & Authenticity: From Ancient Bronzes to Wabi-Sabi

For art historians, conservators, and serious collectors, patina is akin to a fingerprint of time – unique, complex, and almost impossible to perfectly replicate. It plays a critical role in authenticating a piece, helping to confirm its age, provenance, and origin. A vibrant, stable, and well-preserved patina on a centuries-old bronze object is often the most compelling evidence of careful stewardship and a powerful testament to its genuine antiquity.

Consider the Bronzes of Riace, magnificent 5th-century BC Greek statues discovered in the Ionian Sea. Their rich, dark, and subtly green patinas are integral to their identity and historical narrative. Imagine the Renaissance, when the rediscovery of classical bronzes, often beautifully patinated, fueled a new appreciation for the aged aesthetic, influencing artists like Donatello. This valuing of time's mark isn't exclusive to the West; ancient Chinese bronzes from the Shang and Zhou dynasties are revered not just for their form, but for the intricate, often jade-like patinas that indicate their immense age. Early Roman statuary, initially bright and polychrome, now wears a muted, earthy patina that contributes to its solemn grandeur. Japanese aesthetics, particularly wabi-sabi – a worldview centered on the acceptance of transience and imperfection, finding beauty in the natural processes of aging and decay – deeply embrace the beauty of imperfection, transience, and the natural patina of age. Think of a simple, unglazed Raku tea bowl, its surface subtly changing with each use, acquiring a rich, unique luster. It's an appreciation for quiet decay and the wisdom accumulated through time.

This is why trying to fake a natural patina, while certainly attempted, is incredibly difficult to do convincingly. True connoisseurs, I've noticed, possess an almost intuitive understanding of how natural processes unfold, spotting the tell-tale signs of haste or artificial intervention, like an expert reading a landscape where every ripple and shadow tells a specific geological tale. The authenticity often lies in the subtle variations, the depth of color penetration, the consistency across the surface, and the way the patina interacts with the material's microstructure – things that only time and natural processes can truly impart. Unless you have centuries to spare, or a very convincing time machine, you're unlikely to truly fool an expert. It’s the subtle shifts, the way light plays off a surface that has been handled for generations, the deep resonance of colors that have slowly mellowed – these are the non-verbal cues that connect us directly to the past and confirm an object’s true provenance.

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/6/62/An_old_man._Charcoal_drawing._Wellcome_L0026703.jpg, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0

The Economic and Use-History Value of Patina

Beyond just aesthetic and historical authenticity, a good patina significantly enhances an object's monetary value in the art and antiques market. For collectors, a well-preserved, authentic patina is a hallmark of rarity and provenance, often commanding higher prices than a similar object that has been aggressively cleaned or restored. Imagine two identical 18th-century bronze busts: one stripped to its original gleaming metal, the other retaining its centuries-old, rich green-brown patina. The latter could easily fetch 50% or even 100% more at auction, purely due to the integrity of its surface history. It's not just about age; it's about a history of respectful use and care. A patina tells a story not just of time, but of all the hands that touched it, the environments it endured, and the appreciative owners who recognized its evolving beauty. This 'use-history' adds an invaluable layer of narrative that can't be replicated, making the object more desirable and more valuable. Imagine a centuries-old Dutch master painting; its value is not only in the brushstrokes but in the history it carries, much like the works of Rembrandt, whose canvases have witnessed centuries unfold.

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/2b/Amsterdam_-Rijksmuseum_1885-The_Gallery_of_Honour%281st_Floor%29_-De_Nachtwacht-_The_Night_Watch_1642_by_Rembrandt_van_Rijn.png, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0

The Human Touch and Enduring Appeal

I think there's something profoundly human about our appreciation for patina. It represents an acceptance of transience, a recognition that everything changes, and that change, gracefully weathered, can be utterly beautiful. It touches on concepts like memento mori – a reminder of our own mortality and the impermanence of all things – which, paradoxically, can deepen our appreciation for what endures. My own art is often about capturing vibrant, immediate feelings and colors, the pulse of the present moment. But even I, with my focus on the new, can't deny the profound beauty of something that has patiently, gracefully endured the 'then.' Patina adds a layer of depth, character, and quiet wisdom that newness, for all its brilliance, simply can't replicate. It whispers stories of all the hands that have touched it, all the eyes that have admired it, and all the moments it has witnessed. For my contemporary abstract art, while it doesn't await centuries of aging, I often build up layers and textures, creating a sense of history or a journey within the canvas itself, reflecting this universal desire for depth and narrative. Who wouldn't want their art to tell such a rich, inviting story?

https://leelibrary.librarymarket.com/event/pablo-picasso-his-life-and-times-85968, http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/us/

Patina in Contemporary Art: Can You Guide Time's Hand (Ethically)?

Of course, artists are endlessly clever! Not everyone wants to wait centuries for nature to work its magic (and let's be honest, sometimes I'm just impatient). So, for modern sculptures and other art pieces, artists frequently employ chemical treatments or other specialized techniques to create an artificial patina – a process sometimes called chemical patination. This allows them to achieve specific colors, textures, and finishes right from the start, imparting an immediate sense of history, age, or a desired aesthetic quality. They might use various acids (like ferric nitrate for reddish tones on bronze, or strong acids for etching), oxidizers (like liver of sulfur for dark browns and blacks on bronze or copper, or ammonium sulfide for deeper blackening), heat (ranging from torching for subtle blues and purples to kiln firing), or even certain waxes and pigments to accelerate and control the natural patination processes. Each agent offers a unique spectrum of possibilities; for example, cupric nitrate can yield a stunning blue-green, mimicking natural verdigris. It's a deliberate artistic choice, much like exploring textures for abstract paintings.

Contemporary sculptors like Isamu Noguchi (though primarily modern, his work embraces natural forms and materials that lend themselves to patination), Richard Serra with his massive weathered steel forms, or Anish Kapoor's highly polished yet deeply patinated bronze works, all engage with this concept, evoking a sense of ancient history or raw materiality. Even abstract artists who deliberately distress surfaces, like Christopher Wool with his layered, often distressed techniques, often engage with this concept, evoking a sense of ancient history or raw materiality.

When it comes to newly created art, this isn't 'faking' in a deceptive sense. It's a deliberate artistic choice, a legitimate technique to add depth and character to a piece, providing an immediate sense of history or a specific aesthetic. The philosophy here is often to evoke the feeling of age, the story of endurance, or perhaps to make a commentary on our cultural relationship with authenticity and the passage of time. It’s a powerful testament to how much we, as humans, value that 'aged' look and the stories it implies. In my own work, while I don't typically aim for centuries-old effects, I often experiment with layers and textures that hint at depth and a journey, reflecting a similar desire for immediate character and a sense of history that a pristine surface simply can't convey.

However, this is where the ethical lines can become murky. Sometimes, unscrupulous individuals attempt to artificially age antiques or historical objects to deceptively increase their value. This is a very different scenario. True collectors and experts can often discern the difference between a naturally occurring, centuries-old patina and a hastily applied fake. Nature is the ultimate artist, and trying to rush her masterpiece usually results in a clumsy imitation. The authenticity often lies in the subtle variations, the depth of color penetration, the consistency across the surface, and the way the patina interacts with the material's microstructure – things that only time and natural processes can truly impart. Such deceptive practices undermine the integrity of provenance, devalue genuine historical artifacts, and ultimately harm the entire art market. Unless you have centuries to spare, or a very convincing time machine, you're unlikely to truly fool an expert. It’s the subtle shifts, the way light plays off a surface that has been handled for generations, the deep resonance of colors that have slowly mellowed – these are the non-verbal cues that connect us directly to the past.

https://live.staticflickr.com/2871/13401855525_81707f0cc8_b.jpg, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/

Patina in Everyday Life: The Beauty of Well-Used Things

While artists deliberately create patinas for new works, this appreciation for the aged aesthetic is mirrored in the cherished patina of objects we use and love every day. Beyond grand artworks and ancient artifacts, patina graces countless objects in our daily lives, subtly enhancing their character and telling their unique stories. Think of:

- Your Favorite Leather Bag or Wallet: The rich, supple sheen and darkening that develops from countless touches, oils from your skin, and exposure to light is a classic leather patina. It molds the item to your life, making it uniquely yours, a silent companion on your daily adventures.

- A Well-Worn Wooden Cutting Board: The knife marks, the subtle darkening from absorbing oils and moisture, and the smoothing of its edges speak of years of shared meals and culinary adventures. You can almost smell the faint garlic and herbs clinging to its surface, a memory of countless meals.

- An Old Brass Door Handle: The spots where hands have repeatedly gripped it will often be polished and bright, while recessed areas retain a darker, tarnished patina, creating a beautiful contrast that maps human interaction. It's like a physical record of everyone who has passed through.

- Vintage Denim Jeans: The unique fading patterns, creases, and softened fabric are all forms of patina that tell the story of their wearers and journeys. Each rip and fade is a badge of honor, a chapter in a personal history.

- Antique Books: The subtle yellowing and brittleness of pages, the softened corners of the cover, and the faint scent of aged paper – all contribute to the book's patina, inviting us to imagine the hands that have turned its pages over generations. It's a journey into the past, literally in your hands.

- Musical Instruments: The polished areas on an old violin where a hand has rested for decades, or the darkened brass keys on a saxophone from years of playing – these are beautiful testaments to a life of music, a visual symphony of dedication.

- Well-Used Tools: A hammer with a smooth, dark handle from years of gripping, or a wrench with worn edges, tells a story of craftsmanship and hard work. They feel like an extension of the hand that wields them, imbued with experience.

- Old Coins: The subtle discoloration and wear on the raised surfaces of ancient or vintage coins add to their historical appeal and value. Each abrasion a tiny connection to countless hands that have held it through history.

- A Grandfather Clock's Casing: The deep luster on the aged wood, the softened edges, and the subtle darkening around the keyhole or winding mechanisms speak of generations of careful timekeeping, a silent witness to a family's history.

These everyday patinas remind us that beauty isn't always about perfection or newness; it's often found in the signs of a life well-lived and objects well-loved. What treasured objects in your own home proudly bear these marks of time and use?

Patina in Architecture and Urban Environments

Beyond individual objects, patina scales up to shape the very character of our built environment. Think about grand cathedrals, venerable bridges, or even entire cityscapes. The greening of copper domes, the subtle darkening of limestone facades, or the weathered textures of brick walls are all forms of architectural patina. These changes not only tell stories of construction and enduring use but also integrate structures more harmoniously into their natural surroundings. A new bronze statue might initially stand out, but as centuries pass and its surface deepens to a rich green, it feels less like an imposition and more like an organic outgrowth of the park around it. This process creates a visual dialogue between human creation and natural forces, allowing our urban spaces to breathe, age, and tell a collective story that evolves with every passing season. It reminds me that even large-scale, seemingly permanent structures are subject to the same beautiful, slow transformation as the smallest artifact.

Patina as a Metaphor: The Wisdom of Time

Beyond the tangible world of art and objects, patina offers a rich metaphor for life itself. Just as a sculpture acquires depth and character through environmental exposure and human touch, so too do we, as individuals, accumulate our own 'patina' through experience, challenges, and joy. The lines on an elder's face aren't flaws; they are the craquelure of a lived life, each one a testament to laughter, sorrow, and hard-won wisdom. Scars, both visible and invisible, become the unique textures of our personal history. This perspective encourages an acceptance of transience, a reverence for the wisdom that only comes with time, and a deeper appreciation for the beauty found not in pristine perfection, but in the layered, imperfect, and utterly unique journey of existence. It's a powerful reminder that our stories, too, are etched by the relentless yet gentle hand of time, making us uniquely ourselves.

Conservation vs. Restoration: An Ethical Tightrope

The dilemma of 'to clean or not to clean' often leads to a broader discussion in the art world: conservation versus restoration. While often used interchangeably by the public, these terms have distinct meanings and goals. A conservator focuses on preserving an object in its current state, slowing decay, and maintaining its historical integrity, including its patina. They are the guardians of what is. For example, a conservator might stabilize an ancient bronze sculpture with a beautiful, stable green patina, cleaning only surface dirt while leaving the patina intact because it's integral to its history and aesthetic. Restoration, on the other hand, aims to return an object to a perceived 'original' or 'better' state, which might involve altering or removing parts that have aged. This is where the waters get really murky, and often quite contentious.

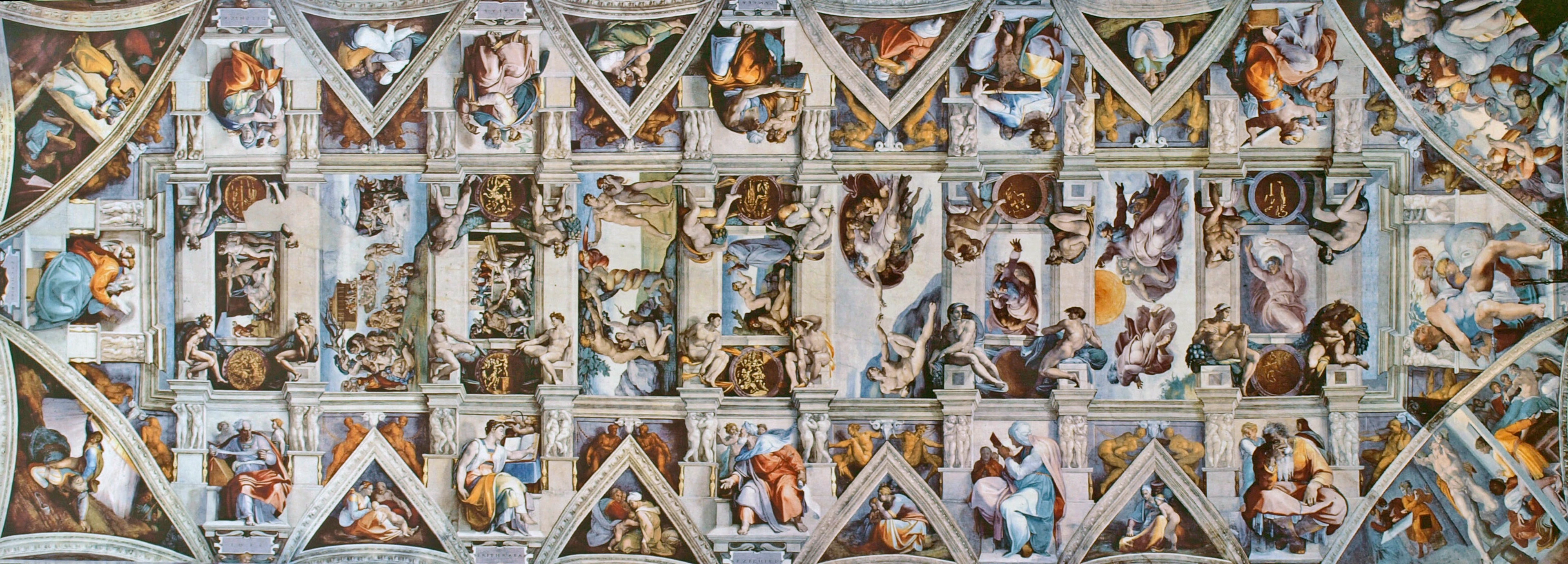

Historically, some restoration efforts, driven by a desire for 'pristine' beauty, have controversially removed centuries of patina. Think of the intense debates surrounding the cleaning of the Sistine Chapel frescoes, for example. While some argued the vibrant colors revealed were the 'true' Michelangelo, others mourned the loss of the aged, softer appearance that centuries had bestowed. Another classic example is the cleaning of old master paintings where layers of darkened varnish (a form of patina) were removed, sometimes revealing colors that were never meant to be seen with such intensity, or altering the delicate balance the artist intended. In another scenario, a conservator might restore a painting with flaking paint and significant losses by carefully inpainting missing areas, but they would still aim to keep the original varnish and its natural craquelure if stable, as it contributes to the painting's age and character. The 19th-century 'restoration' of ancient marble statues, often bleached to stark white, erased centuries of subtle weathering and traces of original polychromy, fundamentally altering our understanding of classical aesthetics. Similarly, the 're-patination' of ancient architectural elements to a uniform, artificial finish strips away the unique geological and environmental narrative of a site.

For ancient Roman bronzes, a perennial debate exists: should they be polished back to their gleaming original state, or should their millennia-old green patina be preserved? It's a profound ethical tightrope walk. As an artist, I often grapple with the idea of 'finishing' a piece; knowing when to stop, when to let go, when to accept the accidental marks as part of its story. This mirrors the conservator's dilemma: when does intervention become an erasure? Those who walk this tightrope, the dedicated conservators, are the quiet heroes of our cultural heritage, often found in places like my museum in 's-Hertogenbosch. They strive to understand the artist's original intent, the historical context, and the material's integrity, weighing the potential benefits of intervention against the irreversible loss of historical evidence embodied in the patina.

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/0/07/CAPPELLA_SISTINA_Ceiling.jpg, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0

To Clean or Not to Clean: The Patina Dilemma

This is a monumental question, especially in the world of art and antiques! For many artworks, particularly those made of metal, wood, or certain stones, removing the patina is often considered a cardinal sin. It's not just stripping away aesthetic beauty; it's frequently damaging the surface and, crucially, erasing vital historical and authenticating information. Think of it as deliberately tearing pages out of a very old, very precious book. Or imagine an old oak tree, deeply furrowed with age. You wouldn't sand down its bark to make it look 'new' again, would you? It's like taking a centuries-old violin and polishing away all the smooth, darkened areas where countless hands have rested, destroying the very evidence of its storied musical life.

My personal rule of thumb (and one widely accepted in the art world) is simple: when in doubt, don't clean it. Imagine you've just acquired a vintage metal sculpture. It has this beautiful, deep green hue, but there are a few dusty spots. Your first instinct might be to grab a spray cleaner, thinking you're 'freshening it up.' But before you do, remember that each speck of dust, each subtle discoloration, might be part of its unique story. Cleaning it with harsh chemicals, abrasive materials, or even vigorous scrubbing can permanently diminish its historical value, its artistic charm, and its market worth. Harsh chemicals might include strong acids or alkalis, while abrasive materials could be anything from steel wool to stiff brushes or even overly aggressive polishing compounds. Imagine cleaning the Statue of Liberty – it would be an outrage! The urge to 'fix' things is strong, but sometimes, the best intervention is no intervention at all (something I have to remind myself of constantly, even in my art!).

That said, there are nuances. Some functional pieces, like certain types of silverware or polished brass, are traditionally meant to be regularly cleaned and shined. And occasionally, a conservator might carefully remove a particularly unstable or aesthetically detrimental patina (like a noxious, actively corroding bronze disease, or deeply ingrained dirt that obscures detail) to save the underlying object. It really depends on the material, the object's original purpose, the artist's intent, and the specific type of patina. If you ever feel a treasured piece needs attention beyond a gentle dusting – perhaps it has active corrosion or significant damage – please, for the love of art, consult a professional conservator. They are the real heroes who understand these delicate balances.

Final Thoughts on Time, Art, and Our Stories

Patina reminds me that art isn't a static, frozen thing. It lives, it breathes, it ages, and it changes, just like us. It accumulates stories, experiences, and a unique character that only the passage of time can bestow. It's a testament to endurance, a quiet defiance against the fleeting nature of things, and a profound collaboration between human creation and the forces of the natural world. In short, patina embodies authenticity, history, and a beauty shaped by patient transformation. It’s also a gentle reminder that even my most vibrant, contemporary abstract works, initially bursting with newness, will one day begin their own subtle journey of aging, accumulating their unique visual histories for future generations. Just as patina forms through layers of interaction, my art often comes alive through layers of paint, texture, and thought, each contributing to a deeper narrative, a slow unfolding of its own story.

So, the next time you encounter an artwork, an antique piece of furniture, an ancient building, or even a well-worn tool that proudly wears its age, take a moment. Look closer. You might just be witnessing a beautiful, slow-motion conversation between material, environment, and time – a conversation that began long ago and continues to unfold even as you stand there. It's a dialogue worth listening to, a narrative that enriches our understanding and appreciation of all art, old and new. Actively seek out patina in museums, antique shops, historical sites, and even in your own home; each mark is a story waiting to be heard.

If you're curious about new art that carries its own vibrant stories, even without centuries of age, I invite you to explore my collection. Perhaps your own new acquisition will begin its journey, slowly acquiring its unique story, its own cherished patina, for future generations to admire. You could even explore my personal artist timeline to see how my own artistic voice has evolved through time, much like a patina forms layer by layer. What treasured objects in your life proudly bear the marks of time and use? I'd love to hear about them.

Frequently Asked Questions About Patina

Q: Does patina always protect the artwork?

A: Often, yes. For many metals, particularly bronze, a stable patina layer (like a bronze carbonate layer) can actually protect the underlying metal from further, more destructive corrosion. It acts as a natural, self-forming shield against the elements, which is a major reason why its removal is often discouraged. However, as discussed in the main article, not all surface changes are protective; rust on iron or active 'bronze disease' are examples of destructive forms of patina. Always assess the type of surface change. Sometimes a patina can be too vibrant or uniform, leading to suspicion of artificial intervention if it's supposed to be natural.

Q: Can I speed up patina formation on my art?

A: Yes, many artists and artisans use various artificial patination techniques, involving chemical treatments (like liver of sulfur for bronze, ferric nitrate for reds, or ammonium sulfide for blacks), heat, or specific waxes, to achieve desired finishes quickly. If you're an artist, experimentation is key! However, if you're a collector considering altering an existing piece, especially an antique or valuable artwork, it's generally best to let natural patina develop over time or to consult a professional conservator. Any attempts to artificially age a valuable item can negatively impact its authenticity and market value.

Q: Are there any materials where patina is always considered detrimental?

A: Yes, absolutely. For instance, the characteristic red rust on steel or iron is a form of oxidation that is usually actively destructive, compromising the material's structural integrity. Similarly, certain types of mold, mildew, or foxing (brown spots) on organic materials like paper or textiles, while a 'surface change over time,' are unequivocally harmful and require careful removal to prevent permanent damage. These are forms of deterioration, not cherished patina.

Q: How can I preserve existing patina on my art?

A: The best way to preserve a stable patina is to ensure a stable environment. This means maintaining consistent temperature and humidity, avoiding direct sunlight or harsh artificial lights, and protecting the object from dust and pollutants with gentle dusting (using soft, dry cloths). Crucially, avoid cleaning with chemicals, abrasives, or vigorous scrubbing. High humidity and salt in coastal environments can accelerate degradation for some materials, so climate control is especially important there. If you notice any active corrosion or deterioration – like a powdery residue or flaking – always consult a professional conservator; they are trained to address specific issues without harming the delicate, stable patina.

Q: What role do conservators play in relation to patina?

A: Conservators play a crucial role as ethical guardians of cultural heritage. They meticulously study the composition of objects and their patinas, assess stability, and make informed decisions on whether to conserve (stabilize and preserve the patina) or, in rare cases, restore (which might involve partial removal of unstable or aesthetically compromising surface layers). Their work involves a delicate balance of science, art history, and ethics, always prioritizing the long-term health and historical integrity of the artwork.

Q: How can you tell the difference between a real and a fake patina?

A: Identifying a fake patina requires an experienced eye, but generally, natural patinas develop slowly and organically, often showing subtle, irregular variations in color and texture, deep integration with the material's microstructure, and consistent growth patterns in sheltered areas. They tend to be stable and feel authentically aged, often with a subtle, deep luster. Fake patinas, in contrast, might appear too uniform, have an artificial sheen or texture, lack the depth of natural coloration, show signs of aggressive chemical application (e.g., drips, uneven coverage in protected areas), or feel superficially applied rather than integral to the object. They often lack the complex chemical layering that only centuries can impart. If you're unsure about a valuable piece, always seek an appraisal from a reputable expert or conservator.

Q: What's the difference between natural and artificial patina?

A: A natural patina forms slowly over time due to genuine environmental exposure, chemical reactions, and/or consistent human touch, making it an authentic record of an object's history. An artificial patina is intentionally created by artists or artisans using controlled chemical treatments, heat, or other techniques to achieve a desired aged appearance on new materials. While artificial patination is a legitimate artistic technique to add character to new works, it is not a substitute for natural patina when evaluating the historical authenticity or antique value of an object.

Q: What are some common misconceptions about patina?

A: One common misconception is that all signs of age are beneficial patina. As we've discussed, destructive rust or aggressive tarnishing are harmful and compromise an object's integrity. Another is that patina can be rushed without compromising authenticity – while artificial patinas have their place in new art, true historical patina cannot be replicated overnight. Some also mistakenly believe that a shiny, "new" appearance is always preferable, overlooking the profound beauty and historical narrative that a well-developed patina offers.

Q: How does patina affect the texture of a material?

A: Patina significantly impacts texture! On metals, it can create a smooth, velvety finish, a granular appearance, or even a rough, pitted surface depending on the compounds formed. On wood, it can soften sharp edges, smooth areas of frequent touch, and enhance the grain's tactile quality, sometimes creating a subtle sheen. For stone, lichens and weathering can etch intricate, uneven patterns, while mineral deposits might create a subtly textured film. Even the craquelure on old paintings adds a delicate network of raised lines, creating a unique visual and tactile experience that a brand-new surface lacks.

Q: Is there a point where patina becomes too much and genuinely detrimental?

A: Absolutely. While a stable, protective patina is desirable, there are forms of surface change that are unequivocally harmful and must be addressed. Active 'bronze disease' on copper alloys, for example, is a destructive, powdery corrosion that can rapidly eat through the metal if left untreated. Similarly, extensive rust on structural iron, deep-seated mold on textiles, or acid degradation of paper all represent points where the 'patina' has become detrimental, compromising the object's integrity and requiring professional intervention to prevent total loss. This is where the distinction between a 'cherished patina' and 'active deterioration' becomes critical.

Q: Does patina always increase an object's value?

A: No. While a stable, authentic, and desirable patina often significantly increases an object's aesthetic and monetary value (especially in antiques and fine art), a detrimental or unstable surface change (like active corrosion, severe tarnish, or excessive biological growth) can actively decrease its value by compromising its integrity or obscuring its original form. The type, stability, and aesthetic quality of the surface change are all crucial factors.

Glossary of Key Patina Terms

- Patina: A surface layer that forms on materials over time due to aging, environmental exposure, or chemical reactions, often enhancing an object's aesthetic and historical value.

- Patina of Age: Surface changes primarily resulting from the sheer passage of time and exposure to natural environmental factors.

- Patina of Use: Surface changes on an object that result from regular handling, wear, and interaction with human hands or daily use.

- Oxidation: A chemical reaction involving the loss of electrons, often causing metals to react with oxygen and moisture, leading to the formation of compounds like rust or the green on bronze.

- Corrosion: The destructive deterioration of a material, usually a metal, by chemical or electrochemical reaction with its environment. While patina is a form of controlled corrosion, many forms of corrosion are harmful.

- Malachite: A green copper carbonate mineral, often a component of the green patina on bronze and copper.

- Azurite: A blue copper carbonate mineral, also commonly found in the patina of copper-based alloys.

- Verdigris: A common blue-green pigment or patina, typically formed on copper, brass, or bronze surfaces when exposed to acetic acid (like from vinegar).

- Tannins/Lignins: Natural organic compounds in wood that contribute to its color changes and patina formation over time.

- Craquelure: The network of fine cracks that develops on the surface of old paintings, typically in the varnish or paint layers, due to aging.

- Saponification: A chemical process where oils (e.g., in paint binders) react to form soap-like compounds, often contributing to varnish degradation and pigment changes in paintings.

- Tarnish: A dulling or darkening surface layer, usually on reactive metals like silver or brass, typically considered undesirable and often removed because it can obscure details or lead to further damage.

- Bronze Disease: An unstable, powdery, and actively corrosive form of patina on bronze, often caused by chlorides, which can be highly destructive and requires professional intervention.

- Conservation: The process of preserving an object in its current state, slowing decay, and maintaining its historical integrity, including its patina. Conducted by a conservator.

- Restoration: The process of returning an object to a perceived 'original' or 'better' state, which may involve altering or removing parts that have aged. Often carried out by a restorer.

- Artificial Patination / Chemical Patination: Techniques employed by artists or artisans to create a desired patina effect quickly using chemical treatments, heat, or other specialized processes on new materials.

- Patination Agent: A chemical substance used to induce or accelerate the formation of an artificial patina on a material, typically metal.

- Provenance: The chronological record of the ownership, custody, or location of a historical object, artwork, or piece of literature. A well-documented provenance confirms authenticity and often increases value.

- Wabi-Sabi: A Japanese aesthetic and worldview centered on the acceptance of transience and imperfection, finding beauty in the natural processes of aging and decay, often visible in patina.

- Weathering: The process of wearing away or changing the appearance or texture of something by long exposure to the atmosphere.

- Glass Sickness: A form of deterioration in glass where alkalis leach from the material, creating an unstable, often iridescent, layered surface.