Holography Art: Sculpting Light, Challenging Reality, & Future Frontiers – Your Ultimate Guide

Dive deep into holography art. This ultimate guide covers foundational science, history, diverse optical & digital techniques, visionary artists, and the profound impact on our perception of reality.

Holography Art: Sculpting Light, Challenging Reality, and Future Frontiers: Your Ultimate Guide

There’s something about light that seems to defy gravity, appearing to float in mid-air, a solid presence born from pure energy. It’s a magic that stops you dead in your tracks, making you question everything you thought you knew about visual perception and the very fabric of reality. I remember the first time I truly saw a hologram – not just a cheap sticker on a credit card, but a genuine, intricate artistic piece. It wasn't merely a 3D image; it was a ghost of reality, shimmering with an otherworldly presence, shifting subtly as I moved, inviting me to step into a space that wasn't physically there. That’s the profound power of holography art, and it’s a subject I’m utterly captivated by. I keep asking myself: what does it truly mean for something to 'be' there, if it lacks physical mass, yet exists tangibly in our space? This feeling of confronting an impossible presence is precisely where the magic of holography lies, a dance between illusion and reality.

It's like witnessing a secret conversation between light and space, a profound dialogue that artists like me harness. In this comprehensive exploration, we’ll delve into the foundational science behind holography, trace its fascinating history, examine the diverse artistic techniques, explore its profound impact on perception, and consider its exhilarating future potential. Ultimately, this article aims to be your definitive guide to understanding how artists sculpt with light, creating illusions that challenge our very understanding of what is real.

What Is Holography Art? Deconstructing the Magic of Light

At its core, holography art is the creation of holograms for artistic expression. But what makes a hologram so fundamentally different from a photograph or even a stereoscopic 3D image? Well, unlike a photograph that merely captures the intensity (brightness) of light from a single perspective – much like how a painter uses different shades or values of color – a hologram records both the intensity and phase (the precise position of each light wave in its cycle) of light waves scattered from an object. Imagine trying to capture a symphony: a photograph would give you a list of the instruments played and their loudness (intensity), but a hologram would capture the full score – every note, every rhythm, every subtle nuance of timing (phase) – allowing you to perfectly recreate the entire performance. This crucial difference is what unlocks the medium's true artistic potential. Recording the phase isn't just a technical detail; it's the key to capturing the spatial information of an object, allowing artists to create a truly volumetric, perspective-shifting illusion rather than a flat representation. It's the difference between seeing a static image of a rippling pond and actually recreating the entire, dynamic wavefront of light as if the original stone were still falling into the water. And that's what makes it so incredibly special.

It’s also important to note early on that while optical holography (light on film) is the traditional form, relying on the actual physical interaction of light waves, digital holography is a rapidly evolving computational approach that creates holographic images using algorithms. But we'll get to that later. For now, let's talk about the mesmerizing dance that makes it all possible.

Holography vs. Other 3D Illusions: Understanding the Key Differences

Before we dive deeper, it's crucial to understand that not all 3D illusions are holograms. Many technologies create compelling visual depth, but they don't operate on the same fundamental principles of wavefront reconstruction. I often get asked, "Is this a hologram?" when people see things like:

- Lenticular Prints: These are flat images that appear to have depth or even animate as you change your viewing angle. They work by layering multiple images and using tiny lenses (lenticules) to direct different images to your eyes depending on your perspective. Think of those 'magic eye' cards or postcards where an image seems to move. They offer a limited form of parallax but don't reconstruct a full light field.

- Stereoscopic Images (like 3D Movies): These rely on presenting slightly different 2D images to each eye, which your brain then fuses into a single 3D perception. This is why you need special glasses. They create an illusion of depth but lack true parallax – if you move your head, your perspective on the objects in the scene doesn't change naturally as it would in real life.

- Pepper's Ghost: This is an old theatrical trick (dating back to the 19th century!) that uses a sheet of glass or a semi-transparent mirror to reflect an off-stage image, making it appear as if a translucent "ghost" is floating on stage. It's a clever optical illusion, but it's a reflection of a flat image, not a true 3D light field reconstruction.

True holography, by contrast, doesn't rely on tricks of perception or separate images for each eye. It actually recreates the physical light wavefront from an object, giving you true, full parallax where your perspective shifts naturally as you move around it, revealing previously hidden parts of the scene. It's less of an illusion and more of a light-based re-presentation of reality itself. And that, for me, is the mind-bending difference.

The Dance of Light: Phase, Interference, and Wavefront Reconstruction Explained

When I try to explain this to friends, their eyes often glaze over at the mention of 'phase' and 'coherence.' My shortcut? Imagine a synchronized swimming team. A regular camera captures their position (intensity). But a hologram captures their exact position and the precise moment each swimmer begins their kick or stroke (phase) – their perfect, unified rhythm. When recreated, you don't just see a static image; you see the potential for their movement in space, from every angle. It's like knowing not just that a wave moved, but the exact timing and height of every ripple, allowing you to recreate the original disturbance with uncanny fidelity. What makes phase so crucial for capturing spatial information is that the relative phase between different light waves encodes the three-dimensional structure of the object. A light wave traveling from a point closer to you will have a different phase relationship to a reference wave than a light wave traveling from a point further away. Recording these tiny phase differences across the entire wavefront is what allows the hologram to reconstruct the object's depth.

This interaction, where waves either reinforce or cancel each other out, is called interference. When two coherent light beams (light waves that are in phase and travel in unison, usually from a laser, which is why lasers are crucial for traditional holography) meet, they create an intricate, microscopic pattern of light and dark fringes. This pattern – where light waves constructively interfere (add up to be brighter) or destructively interfere (cancel each other out to be darker) – is then meticulously recorded on a light-sensitive medium, often a holographic plate with a specialized emulsion layer. Think of it like a highly detailed fingerprint of the light, capturing not just its brightness but the precise timing of every peak and trough of the waves.

What’s groundbreaking is that by capturing this interference pattern, you're not just recording light's brightness; you're also recording its phase – the precise timing and position of each light wave in its cycle. This is like knowing not just that a dancer moved, but their exact pose at every microsecond, or like replaying a perfect symphony, not just the notes but the acoustics of the hall itself. When you illuminate this recorded pattern with the original reference beam, the pattern acts like an incredibly complex diffraction grating, meticulously reconstructing the original light wavefront that came from the object. This process, known as wavefront reconstruction, is what gives you that uncanny, full-parallax, three-dimensional illusion. Parallax here means that as you move around the hologram, your perspective shifts, revealing different parts of the image and hiding others – if you move your head to the left, you see more of the right side of the object, just as you would in real life. It makes the holographic artwork feel alive and interactive, truly changing with your movement, unlike a static image. It's not just a picture of something; it is the light from something, captured and re-presented. Mind-bending, right? This intricate dance of light, captured and replayed, is what provides artists with a palette beyond imagination.

More Than Just a Trick: Holography Art Challenging Perception and Reality

This fundamental scientific principle is the bedrock upon which artists build their unique creations, leading us to explore how this technology transcends mere novelty to become a profound artistic medium. Now, you might be thinking, "Okay, cool tech, but is it art?" Absolutely. Just like the history of photography as fine art reshaped our understanding of visual expression, facing initial skepticism before being embraced, holography pushes the boundaries of what's possible. Artists aren't just making pretty 3D pictures; they're exploring profound themes of perception, presence versus absence, the nature of reality, and illusion itself. They're playing with light as a medium, sculpting with photons rather than pigment or clay. It's a fundamental challenge to our visual assumptions, asking us to look deeper than the surface and engage actively with what we see. For me, this resonates deeply with how I approach what is design in art in my own abstract paintings, constantly seeking new ways to manipulate form and light to evoke emotion and meaning. A holographic portrait, for example, doesn't just show a face; it embodies a profound exploration of presence versus absence, the very fabric of being (ontology), and how we ascertain reality (epistemology), forcing us to confront the ephemeral nature of existence and memory, questioning what it truly means for something to 'be' there. It also delves into phenomenology, challenging how things appear to us, and creating an uncanny valley effect where the hyper-realistic, yet immaterial, representation feels unsettlingly familiar but ultimately alien – almost human, but not quite. It is, in essence, art that confronts you with your own mind, your own qualia – the subjective, conscious experience of perception itself. It directly engages with embodied cognition, where our perception is intertwined with our physical interaction with the world, making the act of viewing a truly active, rather than passive, experience. It’s this profound psychological impact that makes holography a truly unique medium.

A Brief Journey Through Holographic History: Accidental Brilliance

While holography might feel like something out of a futuristic movie, its theoretical groundwork was laid surprisingly early, building on centuries of understanding light as a wave. Dennis Gabor first conceived the theory of holography in 1947, earning him a Nobel Prize. He was actually trying to improve electron microscopes, not invent a new art form! However, Gabor's early efforts were limited by the lack of a suitable light source, often resulting in blurry images – a frustrating technical hurdle that kept true 3D visual holography in the realm of theory for a while. But the real breakthrough for visual, three-dimensional holograms didn't come until the 1960s with the invention of the laser, which provided the crucial coherent light needed for effective wavefront reconstruction. The laser didn't just solve a technical problem; it handed artists a brush made of pure light, a tool to literally sculpt with photons, opening a completely new artistic dimension.

It's a story that always resonates with my own process of discovery in art – how a seemingly disparate thread can unexpectedly lead to a breakthrough. Gabor's accidental Nobel Prize is a perfect illustration of this beautiful randomness, this serendipity of innovation, that often propels both scientific discovery and artistic creation. In the art world, pioneers quickly seized on this new medium. Suddenly, they had a tool to create art that literally occupied space without physical mass, challenging concepts of form and dimensionality that artists have grappled with for centuries. It's been a wild ride, and here are a few milestones:

Year | Key Development/Figure | Significance for Holography Art |

|---|---|---|

| 1947 | Dennis Gabor | Theoretical foundation laid; coined "hologram." Though not immediately practical for 3D imagery due to technical limitations (like the lack of coherent light), it established the core principle of wavefront recording, sparking theoretical artistic possibilities. |

| 1960 | Invention of the Laser | Provided the crucial coherent light source, transforming holography from a theoretical concept into a practical visual medium, making artistic exploration truly possible by giving artists a tool to literally sculpt with photons. |

| 1962 | Yuri Denisyuk & Emmett Leith/Juris Upatnieks | Independently produced the first high-quality 3D optical holograms using lasers, demonstrating the stunning visual potential that captivated early experimental artists and studios, proving holography's artistic viability. |

| 1968 | Stephen A. Benton | Developed the white-light transmission hologram (often called a "rainbow hologram"), which made holograms viewable with ordinary white light (not just lasers), a monumental step for widespread artistic display and accessibility, ushering holography into galleries and public spaces by making it more robust and easier to illuminate. |

| 1970s-80s | Emergence of Holography Studios/Galleries | Artists began exploring holography as a serious art medium globally; first large-scale holographic installations appeared, pushing the boundaries of what art could be, and leading to its initial recognition as a niche art form with dedicated exhibition spaces and a growing community of practitioners. |

| 1980s | Adolf Lohmann & David Parker | Lohmann, for his theoretical work in computer-generated holography, and Parker for his significant contributions to advanced optical techniques in display holography, further pushing the medium's creative potential. |

| 11990s | Early Digital Holography | Emergence of computational methods for generating holographic images, laying the groundwork for real-time manipulation and animation, though early systems were primitive. |

The Art of the Impossible: Techniques and Types of Holograms

Understanding the historical arc reveals not only the evolution of the technology but also the diverse ways artists began to harness its unique properties. When I talk about holography, people often assume there’s just one type, but it’s a diverse field with various techniques, each offering different aesthetic possibilities. It’s a bit like different types of abstract art – same broad category, wildly different results. Understanding these distinctions and their underlying media is key to appreciating the artists' mastery.

Transmission Holograms: Looking Through a Window to Another Dimension

These are often the ones we first think of when we imagine a hologram. Light is shone through the hologram plate to reconstruct the image on the other side. They usually require a specific, coherent light source (often a laser or a precise point source of white light, as with Benton's innovations) and can create incredibly deep, realistic 3D scenes that appear to float behind the plate. It's truly like looking through a window into another dimension, and the depth can be astonishing. I’ve seen pieces where it feels like you could step right into the scene, an invitation to a space that doesn't physically exist. While traditionally monochromatic, achieving full-colour transmission holography is possible, though technically challenging. This is because it requires recording and reconstructing multiple wavelengths (colors) without unwanted interference or 'crosstalk' between the color channels, often necessitating complex multi-laser setups or sequential exposures – which means using multiple lasers simultaneously or taking separate exposures for each color, a technically demanding feat. A common type, the rainbow hologram (a specific kind of white-light transmission hologram pioneered by Benton), sacrifices vertical parallax for full spectral color reproduction from horizontal movement, giving that familiar iridescent effect and significantly increasing display accessibility. It's important to remember that even a rainbow hologram, despite its vibrant visual effect, is still fundamentally a transmission hologram, relying on light passing through it. For display in ambient light conditions, artists sometimes use specific diffuse backlighting or integrate the hologram into light boxes designed to minimize reflections and maintain image clarity, although a precise point source is always optimal for full depth and crispness.

Reflection Holograms: Shimmering Jewels of Light

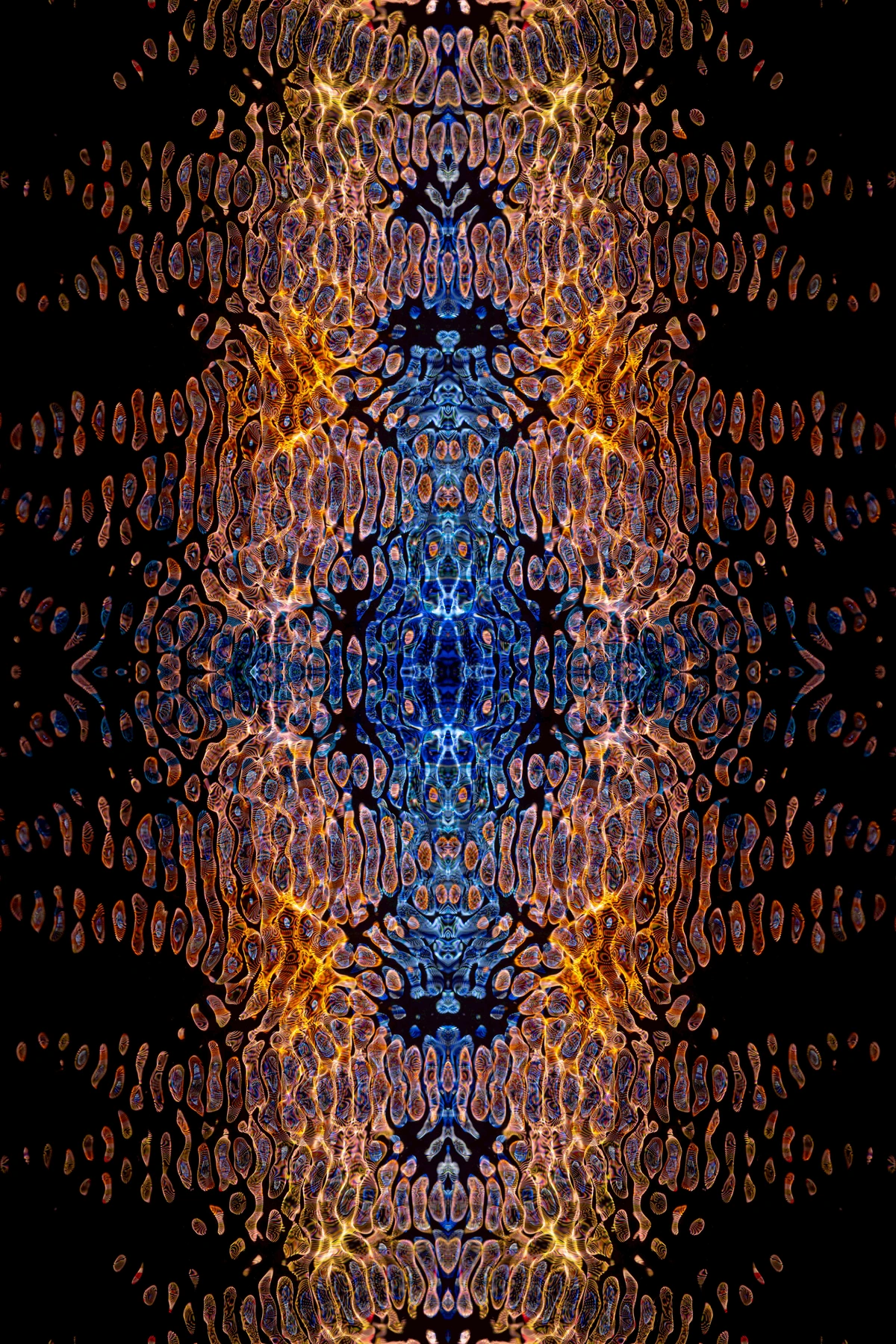

True reflection holograms are fundamentally different; you view them by light reflected from the hologram surface, not transmitted through it. They are recorded and viewed using reflected light from the front, much like looking at a physical object. These are also viewable with ordinary white light, and the image often appears to project in front of, on, or through the plate. These are the dazzling, often jewel-like holograms you might see that shimmer with spectral colors – like a rainbow caught in ice – as you move around them. These spectral colors are caused by the hologram acting as a complex diffraction grating, essentially a finely structured surface embedded in the emulsion layer that bends light into its constituent colors, much like a prism splits white light. This splitting occurs because the very fine, layered interference patterns within the emulsion preferentially reflect specific wavelengths of light depending on the viewing angle, making it appear as if the light is emanating directly from the artwork. I find these particularly captivating because they interact with the ambient light of a space, becoming living, breathing objects that constantly change with the viewer's perspective and surrounding illumination, making them incredibly dynamic and giving a palpable sense of the light emanating from the artwork itself.

Recording Media: Beyond the Film

While we often speak of "holographic plates" or "film," the specific material used to record the interference pattern is crucial and impacts the final artwork. Beyond traditional silver-halide photographic emulsions, artists also utilize:

- Silver-Halide Emulsions: These are the traditional choice, similar to black-and-white photographic film, but with much finer grain. They offer incredibly high resolution and sensitivity, making them ideal for capturing complex interference patterns and deep images. The trade-off? They require darkroom processing with chemical developers and fixers, which can be time-consuming, environmentally impactful, and, as I've found, a true test of patience to get just right. They are also prone to shrinking during processing, which can cause image distortion or color shifts if not carefully managed.

- Photopolymers: These light-sensitive plastic materials change their refractive index (how light bends through them) when exposed to light, recording the hologram. They are often less chemically intensive to process than silver-halide and can offer high diffraction efficiency, making for brighter holograms. However, they can be more expensive and sensitive to UV light. Artists value their cleaner processing and durability for certain installations, allowing for faster experimental iterations without extensive darkroom work, and are often chosen for their crisp, vibrant reconstructions. They are particularly suited for creating impressive, bright display holograms that can stand up to longer exhibition periods.

- Photorefractive Crystals: These exotic materials can record and erase holograms in real-time, offering possibilities for dynamic, rewritable holographic displays. While highly experimental and not widely accessible for individual artists, they represent a cutting-edge frontier for interactive and evolving holographic art, allowing for transient, reactive light sculptures that can change on command – imagine a holographic figure that slowly fades and reappears, or shifts its posture as you approach. They offer unique artistic control over the temporal dimension of light, effectively turning light itself into a mutable, living medium.

Each medium presents its own set of advantages and challenges, pushing artists to innovate not just in what they create, but how.

Digital Holography: The Evolving Frontier of Computational Light

With advancements in computing and display technology, digital holography is becoming increasingly prevalent. This involves creating holographic images computationally using complex algorithms (like Fourier transforms, a mathematical tool for decomposing waveforms, or wavefront propagation simulations) rather than optical interference, and then displaying them on specialized screens or through sophisticated projection systems. Breaking free from the constraints of physical film, digital holography opens up unparalleled artistic freedom for animation, real-time manipulation, and truly interactive installations. A core component of digital holography is Computer-Generated Holography (CGH), where the interference pattern is calculated and simulated mathematically, often using algorithms like the Fresnel transform to model light propagation and diffraction, allowing artists to create holograms of entirely virtual or non-existent objects.

While optical holography captures a physical wavefront, digital methods reconstruct it virtually. We're seeing artists experiment with interactive digital holograms using technologies like:

- Light-field displays: These project slightly different images in different directions, allowing glasses-free 3D viewing from multiple angles, much like looking through a window. Artists use these to create immersive, multi-perspective digital sculptures that don't require external viewing apparatus.

- Volumetric displays: Generating points of light in true 3D space, visible from all 360 degrees. Imagine a solid, luminous form floating in mid-air that you can walk around and see from every side, like the Looking Glass displays used by artists such as Joanie Lemercier for captivating light installations.

- Electro-holographic displays: Using spatial light modulators to reconstruct wavefronts. These are often at the cutting edge, offering potential for full-motion holographic video and highly detailed, dynamic volumetric projections.

These push the medium into new, exciting territories, allowing for hyper-realistic visual effects and even the possibility of holographic video, bringing moving, volumetric scenes to life. As an artist who values the unique 'aura' of a physical artwork, I approach purely digital representations with a healthy skepticism about their permanence and the traditional sense of uniqueness. My personal caution stems from concerns regarding true artistic longevity, the environmental impact of such technologies, and whether a blockchain 'receipt' truly confers inherent artistic worth or simply market speculation, particularly when considering the ease of digital replication and the evolving definition of 'originality' in this new frontier. It’s a fascinating, if sometimes troubling, dialogue around digital scarcity and value that I find myself grappling with.

Here’s a quick overview of the main distinctions:

Feature | Transmission Hologram | Reflection Hologram | Digital Hologram | Embossed Hologram (Commercial) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Light Source | Laser or specific point white light (for rainbow) | White light (spotlight or ambient) | Computer-generated, specialized digital display (light-field, volumetric, electro-holographic) | White light (often diffuse ambient light) |

| Image Location | Appears behind the plate | Appears in front of, on, or through plate | On a specialized digital display, often projecting into real space | On the surface of the material, typically shallow 3D effect. |

| Visual Effect | Deep, realistic 3D window, often monochromatic or filtered full-colour (rainbow), offers remarkable depth and true parallax. Images recede into the plate. | Shimmering, jewel-like, full-colour (spectral), highly interactive with ambient light, often feels like it's projecting forward. Displays vibrant, often single-color, reconstructions. | Highly flexible, interactive, real-time potential, animation, can be dynamic and immersive, limited by display technology. Can achieve full motion and a wide color gamut. | Limited depth, often iridescent, primarily for security/identification. Limited parallax, often looks like a layered sticker. |

| Complexity of Creation | High: Requires laser, vibration-isolation, darkroom, precise chemistry, optical alignment, and significant technical expertise to control interference patterns. | High: Requires laser, vibration-isolation, darkroom, precise chemistry, optical alignment, and significant technical expertise to achieve stable layered structures. | High: Requires advanced computational power, specialized algorithms (e.g., Fourier optics), and often custom display hardware. Focus shifts from physical light manipulation to mathematical modeling and coding. | High for master hologram, low for mass replication (stamping/embossing). |

| Viewing Environment | Often requires specific laser or point light source at precise angle; susceptible to ambient light interference. Best viewed in controlled, often darkened, spaces. Can appear washed out in uncontrolled light. | Easier to display in various settings with good white light; benefits from dedicated spotlight. Its spectral qualities react dynamically to surrounding illumination, making it a living object. | Requires specialized display hardware; can be viewed in diverse settings once displayed, but often needs controlled lighting to maximize visual impact and avoid reflections. Technology is rapidly improving. | Very forgiving, designed for casual viewing in any ambient light, often found on everyday objects like credit cards. |

| Color & Resolution | Typically monochromatic (green or red) with high resolution and deep depth. Rainbow holograms offer spectral color but sacrifice vertical parallax. | Full-color (spectral) with good resolution, often appearing brighter. Colors are inherent to the reflection properties of the recorded layers. | Potential for full RGB color and high resolution, limited primarily by the display technology's pixel density and refresh rate. Rapidly advancing. | Limited resolution, colors are spectral (rainbow-like), not true color. |

Challenges and Limitations of Holography Art: The Practical Realities

But if holography is so revolutionary, why isn't it everywhere? While holography art is undeniably captivating, it's not without its significant challenges. The journey from concept to display can be demanding, and these practical realities often contribute to its niche status within the broader art world:

Technical Complexity: The Finicky Dance of Light and Precision

Creating high-quality optical holograms requires extreme precision. Believe me, this is where my own patience often wears thin, and I usually end up throwing my hands up in exasperation! It's a true labor of love that few master, given the potential for error at every delicate step. This includes:

- Vibration-isolated Environment: A specialized table with air suspension is crucial because even microscopic vibrations during exposure – a heavy truck driving by outside, or a clumsy cough – can destroy the delicate interference pattern. These vibrations cause the light waves to shift relative to each other during the recording, blurring or completely obliterating the intricate pattern that encodes the 3D image. A holographic studio often feels like a sacred, silent temple of light, where absolute stillness is paramount. I've had many a promising exposure ruined by a sudden noise or an accidental bump.

- Powerful Lasers: These are the heart of optical holography, providing the coherent light needed. Examples include Helium-Neon for red light or Argon-ion for blue/green, which can cost thousands of dollars. Each laser has specific power requirements and safety considerations.

- Specialized Optics: Lenses, mirrors, beam splitters, and spatial filters are needed, all requiring micrometre-level alignment. Imagine aligning dozens of tiny, precise components with perfect accuracy; it's a true test of patience! A common error, for instance, is an imperfect beam ratio where the reference and object beams don't have the ideal intensity balance, leading to a weak or noisy reconstruction, or even holographic noise – unwanted scattering or reflections that appear as specks or fogginess in the final image. Artists mitigate this through careful optical design, clean components, and optimizing exposure parameters.

- Light-Sensitive Holographic Plates: These are significantly more expensive than regular film, often costing hundreds of dollars per plate. They are manufactured with extremely fine-grained emulsions to capture the microscopic interference patterns.

- Darkroom and Chemical Processing: A darkroom setup with precise chemical processing is required, akin to traditional analog photography but often even more sensitive to temperature, timing, and chemical concentration. The developer brings out the latent image, and the bleach step often enhances the hologram's brightness and efficiency, turning the silver halides into a transparent refractive index modulation.

It's a demanding process that often involves a blend of artistic vision, scientific expertise, and the unflappable patience of a zen master. My own forays into anything requiring such exactitude usually end with me throwing my hands up in exasperation!

Viewing Conditions: A Specific Kind of Light and Space

Many optical holograms require specific, coherent light sources (like a focused halogen spotlight or a specially designed LED) positioned at precise angles to 'reconstruct' the image effectively. This can make displaying them in diverse settings, especially public ones, quite complex compared to traditional artworks. Artists sometimes overcome this by creating dedicated viewing enclosures, often sleek, minimalist pedestals with integrated lighting, or by designing entire installations where the light source is seamlessly part of the artwork, essentially designing the viewing experience as part of the art itself, almost like a bespoke stage for the light. Furthermore, transmission holograms are particularly susceptible to ambient light interference, which can wash out or distort the image. Exposure to direct sunlight or strong UV light can also degrade the holographic emulsion over time, leading to image fading.

Fragility and Preservation: The Ephemeral Material

Older film-based holograms can be fragile and susceptible to damage from humidity, temperature fluctuations, and improper handling. High humidity can cause the emulsion to swell or warp, while significant temperature shifts can lead to distortions. Their preservation requires careful environmental control – typically a stable temperature between 18-22°C and relative humidity of 40-50% – similar to delicate historical documents or photographs. For silver-halide emulsions, image fading due to chemical reactions or light exposure is a concern, sometimes limiting their archival lifespan to decades without optimal conditions. Photopolymer-based holograms are generally more stable but can still be sensitive to UV light and specific wavelengths of light. Always handle optical holograms by their edges, avoiding touching the emulsion surface, as fingerprints can permanently interfere with light reconstruction. This is a common concern for many contemporary art forms pushing material boundaries, but the light-sensitive nature of holography adds an extra layer of complexity, making the long-term archival challenge a significant consideration for collectors and institutions alike, especially when comparing them to the potential permanence (or impermanence) of digital art forms.

Cost: An Investment in Light

The specialized equipment, materials, and expertise involved in creating and displaying optical holograms can be significant. Lasers, specialized holographic plates, chemical developers, and custom-built vibration-isolation tables represent a substantial investment, making it a relatively expensive art form to produce and collect. The advanced display hardware for digital holography also carries a high initial cost, often in the tens of thousands of dollars for high-resolution volumetric displays, making it a serious financial commitment for individual artists or smaller institutions.

Mass Production Difficulties: The Unique Artifact

While some types of holograms (like embossed security holograms on credit cards) can be mass-produced relatively cheaply, creating unique, high-quality artistic optical holograms remains a meticulous, often one-off process. Each artistic hologram is typically an original optical recording or a limited digital edition, limiting their widespread availability and contributing to their niche appeal. This stands in contrast to the ease of replicating many other digital art forms, such as what is giclee print, which can be reproduced identically in large numbers. For an artist like me, this inherent uniqueness, this sense of a singular moment captured, is part of the deep appeal.

Ethical & Environmental Footprint: The Unseen Costs and Complex Questions

Beyond the practical challenges, the creation and display of holographic art also prompt important environmental and ethical considerations:

- Energy Consumption: Lasers, specialized environmental control systems, and particularly advanced digital holographic displays (like volumetric or electro-holographic systems) can be energy-intensive. A powerful argon-ion laser, for instance, might require significant electrical input and water cooling, potentially consuming as much electricity as several homes during operation. Artists are increasingly grappling with the environmental footprint of their chosen mediums, seeking more sustainable practices or acknowledging the energy demands in their conceptual work.

- Chemical Waste: Traditional optical holography involves chemical processing, similar to analog photography, which generates chemical waste. Responsible disposal and the exploration of more environmentally friendly processing alternatives are ongoing considerations within the field. Think about the careful management of spent developers and fixers, which can contain silver and other heavy metals.

- Ethical Implications of Replication and Digital Identity: As holographic technology advances, the ability to create incredibly lifelike 'digital ghosts' of individuals or even historical artifacts raises profound ethical questions about consent, authenticity, and the nature of representation. What are the implications of digitally replicating a person's likeness without their explicit, ongoing consent, especially after their death? How do we distinguish between an artistic homage and a misleading deepfake? This frontier demands careful consideration as the technology becomes more sophisticated, especially regarding the digital afterlife and our personal identities. Imagine a holographic projection of a deceased musician performing a concert – is that an acceptable artistic tribute or a problematic form of digital necromancy that exploits identity? Or consider holographic memorials that allow you to 'interact' with deceased loved ones; while offering solace, they also blur the lines between memory, presence, and potentially endless digital manipulation. These are the conversations that, frankly, keep me up at night, questioning the boundaries of digital and biological being.

Key Artists Who Shaped the Field: Sculpting with Light

The world of holography art is populated by incredible innovators, artists who truly sculpt with light itself. These pioneers didn't just use a new technology; they redefined what that technology could be, paving the way for future explorations into immateriality and perception.

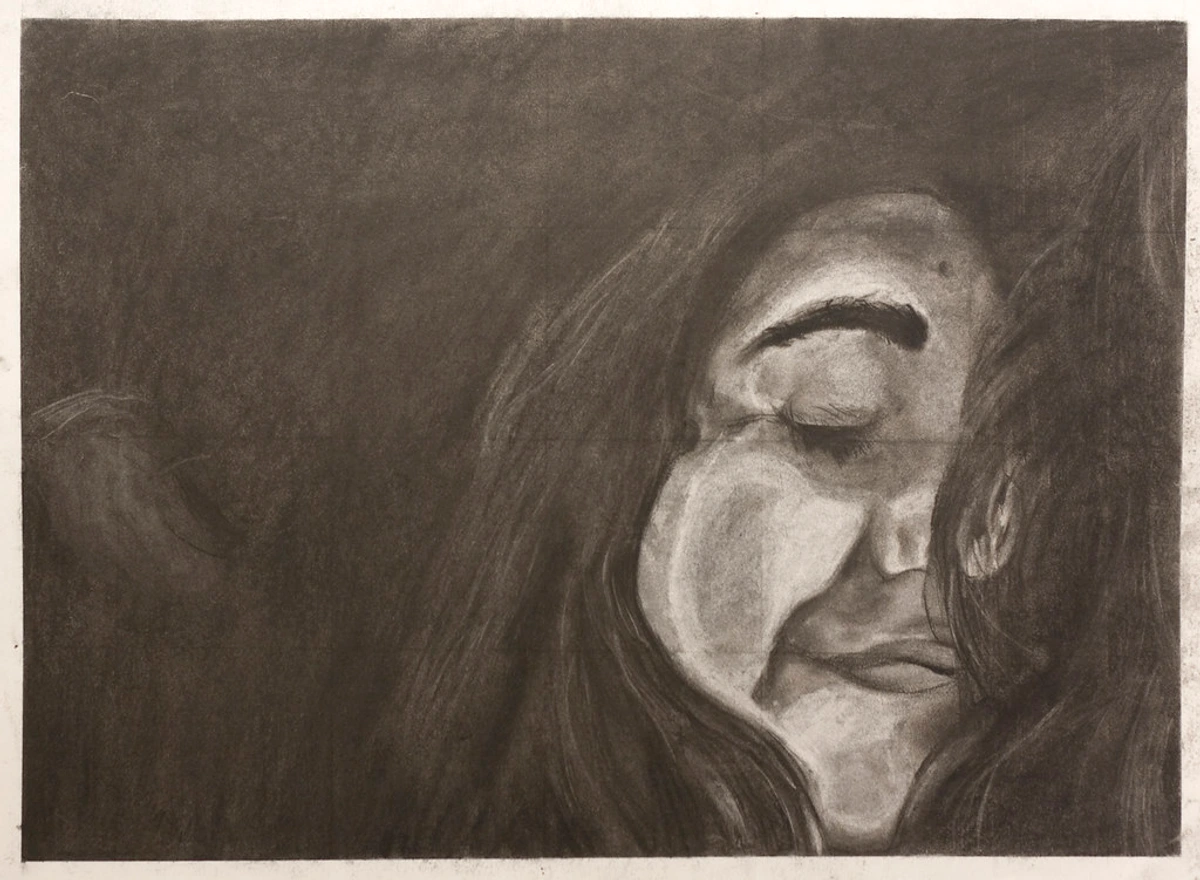

- Rudolph Zouth is renowned for his uncanny holographic portraiture. Works like Portrait of a Young Man challenge the very definition of a likeness, creating lifelike figures that achieve an astonishing depth and presence, making you feel as if the subject is truly there, occupying the same space as the viewer. Zouth's mastery lies in creating an almost unsettling sense of reality in an immaterial form, making the invisible palpable and forcing us to question the tangibility of presence, often exploring the concept of a 'ghostly' or enduring essence.

- Harriet Casdin-Silver, a true pioneer, delved into large-scale holographic installations and abstract forms, often incorporating social commentary, particularly exploring feminist themes, the body, and identity. Her monumental works, such as Ruby and the Calico Cat (a hypothetical title reflecting her known themes), proved that holography could be a powerful medium for profound conceptual exploration, moving beyond simple representation and engaging with societal narratives around female identity and self-perception, using light to dissect cultural constructs of visibility. Her work often gave form to the ephemeral aspects of self.

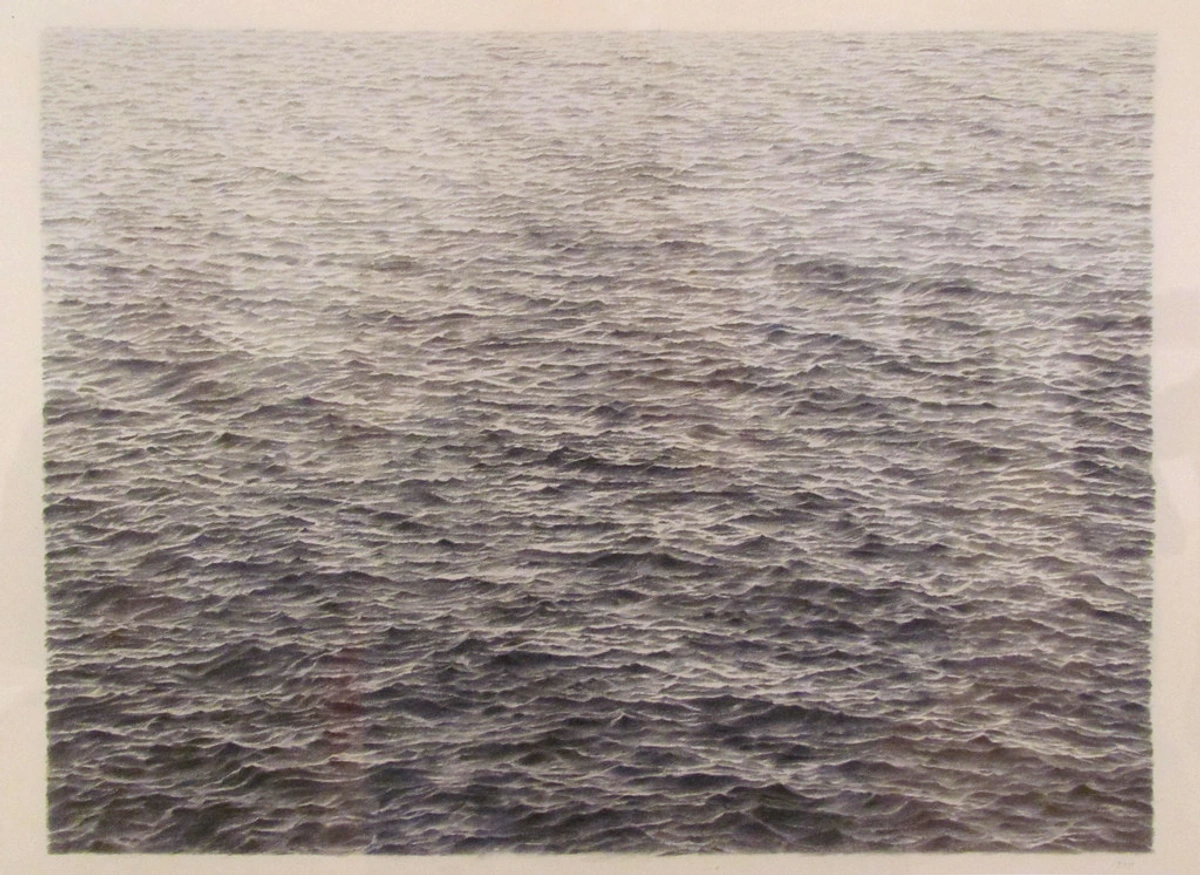

- Dieter Jung, with his mesmerizing abstract light compositions, uses holography to explore the very essence of light as a medium. His pieces, like Light, Space, and Time, often feel incredibly spiritual and contemplative, pushing the boundaries of what what is design in art can achieve with pure light, evoking a sense of cosmic interconnectedness and the infinite. Jung's work often transforms light into a meditative experience, drawing the viewer into a universe of shifting forms and ethereal colors.

- Margaret Benyon, a British artist, is considered one of the first artists globally to seriously experiment with holography in the late 1960s. Her work often explored the female nude and self-portraiture, using the holographic medium to challenge conventional representation by introducing a spectral, elusive quality to the body, delving into issues of perception, identity, and the gaze. Her early explorations were crucial in establishing holography's artistic legitimacy, proving it was a serious medium for introspective and critical work.

- Ana Maria Nicholson, often collaborating with Rudolph Zouth, is celebrated for her exceptional skill in holographic portraiture, particularly capturing subtle expressions and the ephemeral quality of human presence in light. Her works often focus on the intimate and the psychological, making the invisible palpable and inviting a quiet contemplation of human experience, such as in her nuanced portraits that seem to breathe with captured light.

- Seth Riskin combines performance art with digital holography. His interactive works use light to create extensions of the body, blurring the lines between performer, audience, and the luminous artwork itself, pushing into themes of virtual embodiment and ephemeral presence. In pieces like Liquid Light, Riskin explores how digital light can become a direct extension of human movement and expression, turning the body into a conduit for light and creating fluid, reactive sculptures.

- Melissa Crenshaw is known for her ethereal holographic figures and installations that profoundly challenge perceptions of reality. Through works like The Absent Presence, she creates figures that are undeniably 'there' yet entirely immaterial, forcing viewers into a visceral questioning of what constitutes real presence versus perceived illusion, often evoking themes of memory and loss, and the haunting quality of what is almost, but not quite, tangible.

- Sally Weber is recognized for her large-scale holographic installations that often incorporate movement and sound, creating immersive and contemplative environments. Her work pushes the boundaries of spatial experience, turning light into an architectural element that responds to the viewer's journey through a space, crafting multi-sensory light narratives, as seen in pieces that use shifting light patterns to guide the viewer's experience.

- Roger Easton is a foundational figure whose contributions to transmission holography, especially his groundbreaking work at the MIT Media Lab, significantly advanced the technical and aesthetic potential of the medium. His artistic explorations often pushed the boundaries of multi-channel holographic imaging.

- Al Razutis is an experimental artist and filmmaker, a true pioneer in holographic art and video. His early work with multi-exposure holograms and his integration of holographic imagery into film and mixed-media installations challenged conventional cinematic perception and explored the medium's narrative capabilities.

When I look at their work, I’m reminded that artistic vision, truly, knows no bounds. These artists, through their diverse approaches, have collectively broadened our understanding of art, light, and reality.

Holographic Sculpture: Beyond the Flat Plate

While many holograms are flat plates or films, some artists push the boundaries into holographic sculpture. This involves creating three-dimensional forms using multiple holographic elements, often integrated into physical structures or displayed in unique configurations to create complex volumetric displays. Imagine a cube or sphere where each face is a hologram, or a series of plates arranged in space, each revealing a different aspect of a larger, composite holographic image. Artists might also project holograms onto fog or water screens, creating ephemeral, interactive sculptures that blur the line between light and physical presence. This approach moves beyond the 'window' effect of traditional holograms, transforming light itself into a tangible, architectural element that defines space and form.

Why Holography Art Matters: Bridging Worlds and Challenging Realities

Holography art, for me, sits at a fascinating intersection. It’s part of a broader conversation about the ultimate guide to abstract art movements from early pioneers to contemporary trends, pushing against traditional definitions and embracing technology. It's a medium that inherently challenges perception, much like some of the more mind-bending abstract art movements do. It forces us to reconsider the very elements of art – how light, space, and time can be manipulated to create meaning. Its significance lies in several key areas:

- Dimensionality without Mass: Holography offers a unique artistic solution to creating volume and depth without using physical materials in the traditional sense. This opens up entirely new aesthetic and philosophical possibilities, allowing artists to explore themes of immateriality, the intangible, and even the spiritual, representing ideas that defy concrete form. Just as I manipulate color and line to suggest depth where none physically exists on a canvas, holography sculpts with pure light to create form from nothing. It confronts us with the very nature of presence and absence; is something 'there' if it has no mass? This pushes us to confront questions of consciousness, memory, and the elusive quality of being. Think of it as a tangible echo of existence – an exploration that deeply resonates with my own abstract painting process, where I strive to create immersive illusions of space and depth using only pigment.

- Challenging Perception: It makes us acutely aware of how we see and interpret the world. Is what we're seeing 'real' if it has no physical mass? A holographic portrait, for example, can evoke a profound sense of presence, almost like a ghost in the room, forcing us to confront the ephemeral nature of existence and memory. Artists like Melissa Crenshaw, through her ethereal holographic figures, force a visceral questioning of reality, prompting viewers to doubt the tangibility of what they see and inviting a deeper consideration of the 'real' versus the 'perceived,' often blurring the lines between objective and subjective experience. It's a direct invitation to question your own visual certainty, engaging deeply with embodied cognition and the very structure of our sensory experience.

- Bridging Art and Science: Holography is inherently a scientific process, but in the hands of an artist, it becomes a poetic exploration. It’s a beautiful example of how rigorous scientific principles can intertwine with boundless creativity to produce something profoundly moving. Beyond art, holography finds applications in fields like data storage (e.g., storing vast amounts of data in a crystal, offering high-density, secure storage), medical imaging (e.g., creating 3D visualizations of organs for surgical planning or educational purposes, allowing doctors to 'look inside' the body), archival science (preserving delicate artifacts in true 3D, enabling virtual handling and study), and security features (think credit cards or banknotes, where holograms offer robust anti-counterfeiting measures), underscoring the deep scientific roots that artists creatively repurpose. This constant dialogue between the lab and the studio reminds me of the intricate play of light and shadow in my own work, drawing parallels to how I explore the definitive guide to understanding light in art.

- The Viewer's Role as Participant: Unlike a painting or sculpture where the viewer is often a passive observer, holographic art demands active engagement. The illusion of depth and parallax is only fully revealed as the viewer moves, shifting their perspective and becoming an integral part of the artwork's experience. Move left, and you see more of the right side of the image; move up, and you reveal hidden details from below. For example, in a holographic diorama by an artist like John Kaufman (a hypothetical artist known for intricate narrative holograms), moving around the piece might reveal a hidden figure emerging from behind a holographic tree, or a previously obscured message on a wall. This interaction makes the viewer a co-creator, completing the illusion through their movement and unique viewpoint. Sometimes, the art even incorporates sensors for true interactivity, further blurring the line between audience and artwork and creating a truly unique relationship with the piece, deeply engaging embodied cognition.

- Psychological Impact: Beyond mere perception, holography can evoke powerful emotional and psychological responses. The uncanny valley effect, the feeling of confronting a 'ghost' or an impossible presence, can trigger introspection about memory, loss, and the nature of consciousness. This ability to create a profound emotional resonance through immaterial light is a unique artistic frontier, touching upon the subjective experience of qualia and challenging our inherent understanding of what constitutes a 'real' presence. Holography art, in essence, becomes a mirror, reflecting our own inner world and questioning our sense of reality.

Holographic Art in Education and Public Outreach

Holography is not just confined to galleries; it also serves as a powerful tool for education and public engagement. Its ability to present complex 3D information in an intuitive, interactive way makes it ideal for teaching scientific concepts, from wave physics to anatomy. Imagine a holographic projection of a beating heart in a medical school, allowing students to examine it from all angles without dissection. Public installations of holographic art often aim to demystify the technology and spark curiosity, making advanced optics accessible and inspiring a new generation to explore the intersection of art and science. It's a medium that inherently invites wonder, making abstract concepts tangible and exciting.

The Future of Holography Art: Digital Horizons and New Realities

As technology sprints forward, so too does the potential for holographic art. The most exciting developments lie in the seamless integration of digital innovation with artistic vision, pushing the medium into truly immersive and interactive realms. Despite the challenges, the pursuit of holographic art continues to push boundaries, leading us to explore exciting new frontiers.

- Immersive Installations and Public Spaces: Imagine walking into an entire gallery filled with projected holographic environments, reacting to your presence. The evolution of volumetric displays (which create true 3D images in space, viewable from all angles without glasses) and advanced projection mapping allows for truly large-scale, interactive holographic experiences that envelop the viewer, creating fully realized, though intangible, worlds. This moves beyond a 'window' to a 'room' of light you can literally explore. Imagine performance artists interacting with projected holographic partners, or ephemeral holographic forms augmenting physical sculptures in urban spaces, transforming cityscapes into dynamic art galleries. It's a vision of art you don't just see, but inhabit.

- Real-time & Interactive Art: Digital holography enables artists to create dynamic pieces that change in real-time, responding to external data, viewer input (e.g., via gesture control or movement tracking), or even biometric feedback. This opens doors for truly personal and evolving artworks, breaking the static nature of traditional media. Think of light sculptures that evolve as you contemplate them, narratives that branch based on audience participation, or an artwork that subtly mirrors your emotional state through light shifts. The integration of AI could also lead to generative holographic art, where algorithms create constantly evolving, unique holographic compositions based on artistic parameters, reacting to environmental factors or even collective human sentiment. It transforms passive viewing into an active dialogue with the artwork.

- Bridging Virtual and Physical Realities: Future holographic art might blur the lines between virtual reality, augmented reality, and the physical world. Holographic augmented reality could overlay digital information or fully volumetric holographic objects onto physical spaces, creating ephemeral holographic sculptures that appear within a physical gallery, interacting with its architecture. It could even create 'tangible' digital objects that we can interact with through haptic feedback, merging digital presence with physical interaction. This is an exciting, albeit complex, frontier, promising new forms of mixed-reality art where the digital ghost finally steps into our world, inviting us to touch and feel the immaterial.

- Holographic Video and Storytelling: The development of holographic video – dynamic, moving holographic images – promises entirely new forms of narrative art. Achieving truly high-quality holographic video involves significant technical hurdles, including high frame rates, large data processing, and displays capable of rendering realistic motion while maintaining true volumetric properties and full parallax across wide viewing angles. Despite these challenges, imagine watching a story unfold not on a flat screen, but as volumetric figures performing in real space, or experiencing historical events reconstructed holographically with unprecedented realism. This could revolutionize museum exhibitions, performance art, and even personal storytelling, bringing historical figures to 'life' in compelling new ways that challenge our perception of time and memory.

These evolving frontiers demonstrate that holography art is far from static. It's a living, breathing, constantly reinventing medium that promises to challenge our perceptions of reality for generations to come.

Key Takeaways on Holography Art: Your Quick Guide

To synthesize our journey through the magic of light, here are the essential points to remember about holography art:

- More Than 3D: Holography isn't just 3D imagery; it reconstructs the actual light wavefront, offering full parallax and a true volumetric illusion that changes with your movement. It captures the spatial information of an object, making it appear truly present.

- Art & Science Intertwined: Born from rigorous scientific discovery (Gabor's theory, laser invention), holography quickly became an artistic medium, blending technical precision with boundless creativity and finding applications in science and industry.

- Diverse Techniques & Media: From deep transmission holograms to shimmering reflection holograms and the dynamic realm of digital holography, utilizing various recording materials like silver-halide, photopolymers, and photorefractive crystals, artists have many ways to sculpt with light.

- Challenging Reality & Perception: Holographic art profoundly questions perception, presence, and the nature of reality itself, inviting viewers to actively participate in the artwork's illusion and reflect on their own visual certainty and subjective experience (qualia).

- Future is Digital & Interactive: The medium is rapidly evolving with digital technologies and AI, promising immersive installations, real-time interactivity, holographic video, and a blurring of virtual and physical worlds, moving towards art you can inhabit.

- Ethical & Environmental Dialogue: This art form increasingly prompts discussions around energy consumption, chemical waste, and the profound ethical implications of digital replication, consent, and digital identity in a hyper-realistic world, as well as the challenges of long-term archival permanence for some holographic materials.

Frequently Asked Questions About Holography Art

Q: What's the difference between a hologram and other 3D images (like 3D movies or VR)?

A: Not quite! While holograms are undeniably 3D, they're fundamentally different from other 3D imaging techniques like stereoscopic images (which present slightly different 2D images to each eye to create an illusion of depth), lenticular prints (which use tiny lenses to show different images from different angles), or Virtual Reality (VR), where you're immersed in a simulated 3D environment via screens and lenses. Holography, by contrast, reconstructs the actual light wavefront from an object, giving you a true parallax view. This means you can move around it and see different perspectives, revealing previously hidden parts of the object, just like a real object. It recreates the physical light itself, making it a truly volumetric experience that projects an image into your real space, rather than placing you within a simulated space. While a stereogram relies on showing slightly different flat images to each eye to create a perception of depth, a hologram records and reconstructs the full three-dimensional light field, giving you true perspective changes as you move. It is often described as creating an optical illusion art form that is genuinely spatial.

Q: How difficult is it to create a traditional optical hologram vs. a digital one?

A: Historically, creating high-quality optical holograms requires extreme precision: a vibration-isolated environment, powerful lasers, specialized optics, highly sensitive photographic plates, and a darkroom with precise chemical processing. It's a demanding process that blends art and science! However, digital holography is making the creation aspect more accessible through computational methods, as it involves designing light fields mathematically using software. Still, specialized and often expensive display hardware is still needed for viewing the resulting digital holograms, making the display of digital holography challenging in its own way. While optical holography is a highly technical optical illusion art, digital holography shifts the complexity to computation.

Q: Can holography art be bought and collected?

A: Absolutely! Just like any other art form, holographic art is collected by individuals and institutions worldwide. While some pieces are unique (like original film-based optical holograms), others might be produced in limited editions. They do require careful display and lighting, but they are incredibly compelling and unique additions to any collection, offering a distinct visual experience that truly stands apart. Prices can vary widely based on the artist's reputation, the artwork's uniqueness, size, and complexity. Some digital holograms are also now entering the art market, sometimes with unique digital identifiers akin to NFTs, though I tend to approach that particular realm with a healthy dose of artistic skepticism, especially regarding long-term value, environmental impact, and artistic intent versus pure market speculation.

Q: What are Holographic Stereograms?

A: Holographic stereograms are a fascinating hybrid. They aren't true optical holograms in the sense of a single, continuous wavefront recording, but rather composite holograms created from a series of conventional 2D photographs or digital images taken from different perspectives. Each image is then recorded as a narrow strip (or 'slit' hologram) on the holographic plate. When viewed, these strips reconstruct to form a continuous 3D image, often with motion if the original images were a sequence. They are great for displaying moving subjects or computer-generated animations in holographic form, offering good depth and parallax, but they often lack the continuous perspective and deep field of view of a true optical hologram made from a physical object. They're a clever way to bridge conventional imaging with holographic display.

Q: Can I make a hologram with my phone?

A: Not a true optical hologram that records wavefronts in real space. Smartphone apps or certain viewing devices can create simulated holographic effects (often using lenticular technology or 'Pepper's Ghost' illusions) by presenting images that appear to have depth, but they don't reconstruct the actual light field of an object in the same way a true hologram does. A 'Pepper's Ghost' illusion, for example, uses a partially reflective surface to make a flat image appear as if it's floating in space. For now, actual holographic recording remains a specialized process, although digital holography tools are becoming more accessible for artists with computational skills.

Q: How do I properly display a hologram?

A: This is crucial for experiencing a hologram's full potential! Optical holograms often need a specific, coherent light source (like a high-quality halogen spotlight or an LED designed for holograms) positioned at a very precise angle to 'reconstruct' the image effectively. Reflection holograms are a bit more forgiving and can often be viewed with ambient white light, but still benefit immensely from a dedicated, carefully positioned light source to bring out their full brilliance and spectral qualities. Always check the artist's or gallerist's recommendations! Also, avoid exposing optical holograms to direct sunlight or strong UV light, as it can degrade the emulsion over time. Most importantly, always handle optical holograms by their edges, avoiding touching the emulsion surface, as fingerprints can permanently interfere with light reconstruction.

Q: Are there different levels of 'realism' in holography art?

A: Absolutely. Just like painting, holographic art encompasses a wide spectrum of styles and intentions. Some artists strive for hyper-realistic, almost photorealistic holographic portraits or still lifes, aiming to capture every minute detail and create an incredibly tangible sense of presence. Others explore abstract forms, using the holographic medium to sculpt light into ethereal, non-representational compositions that play with color, depth, and movement in purely aesthetic ways. The 'realism' can range from meticulous replication of physical objects to purely conceptual light sculptures that challenge our very definitions of form. It's truly a diverse optical illusion art form.

Q: How does artistic holography differ from commercial applications (like security holograms)?

A: While both use holographic principles, the intent and complexity differ greatly. Commercial security holograms (like those on credit cards or banknotes) are typically mass-produced via embossing, are usually very shallow in depth, and focus on verifiable visual features rather than artistic expression. They are designed for quick recognition and anti-counterfeiting. Artistic holograms, on the other hand, prioritize deep dimensionality, unique aesthetic qualities, and conceptual exploration. They are often one-off or limited editions, meticulously crafted to evoke emotion, challenge perception, or tell a story, rather than for functional security purposes.

Q: Is holography considered a 'new' art form, or is it established?

A: It's an established art form that emerged in the mid-20th century. While it hasn't achieved the widespread commercial recognition of painting or sculpture, it has a rich history, dedicated practitioners (like Stephen Benton, Harriet Casdin-Silver, Dieter Jung, Roger Easton, and Al Razutis), and has been exhibited in major museums and galleries worldwide for decades. It's a niche, but a deeply fascinating and impactful one, continually evolving with technological advancements. So, established but always reinventing itself! It's an art that sculpts with light.

Q: What about the typical dimensions or sizes of holographic artworks?

A: Holographic artworks can vary significantly in size, from small, credit-card-sized pieces to large-scale installations spanning several meters. Traditional optical holograms are often created on plates or films ranging from a few centimeters up to a meter or more in width and height. The practical limits are often dictated by the size of available holographic materials, the optical setup required to illuminate and record them, and the stability of the environment. Digital holographic displays can range from desktop units to large, multi-panel video walls, limited only by current display technology and computational power. The size often influences the viewing experience, with larger pieces allowing for more immersive volumetric effects and spatial imaging.

Q: What about the resolution and color fidelity of holograms?

A: The resolution and color fidelity vary significantly across holographic types. Optical holograms, especially transmission ones, can achieve incredibly high resolution and deep spatial depth, making details very crisp. However, they are often monochromatic (single color) unless complex multi-laser setups are used. Rainbow holograms offer spectral full-color reproduction from horizontal viewing angles, but sacrifice vertical parallax. Reflection holograms inherently display full spectral colors, often appearing brilliant and jewel-like, though sometimes with a slightly lower perceived resolution or shallower depth than the deepest transmission holograms. Digital holography, on the other hand, is limited by the pixel density and refresh rate of its display technology, but is rapidly advancing to offer full RGB color and high resolution, with the added benefit of animation and real-time changes.

My Final Thoughts: Stepping into the Light

I find the whole concept of holography art endlessly fascinating. It's a medium that constantly reminds me that reality isn't always what it seems, and that the boundaries of art are always shifting, always expanding. It asks us to be active viewers, to move, to observe the subtle shifts in light and perspective that unlock its secrets. It’s an art form that doesn't just present an image; it invites you to step into its world, however ephemeral. It feels very much like an extension of how I explore composition and dimension in my own abstract pieces – finding depth and movement where none physically exist, much like a hologram sculpts with light to create illusion.

The ephemeral nature of a hologram, its fleeting presence, only underscores the enduring impact of art itself, reminding us that true wonder lies beyond the tangible. If these explorations of light and perception spark your curiosity, you might find a similar resonance in the abstract dimensions of my own work, available at [/buy], or perhaps delve into the rich historical context of art through the [/den-bosch-museum] or follow my artistic journey on my [/timeline]. There's always something new to discover, isn't there? Ultimately, holography art remains a profound testament to light's boundless potential, forever inviting us to question what we see and imagine what could be.