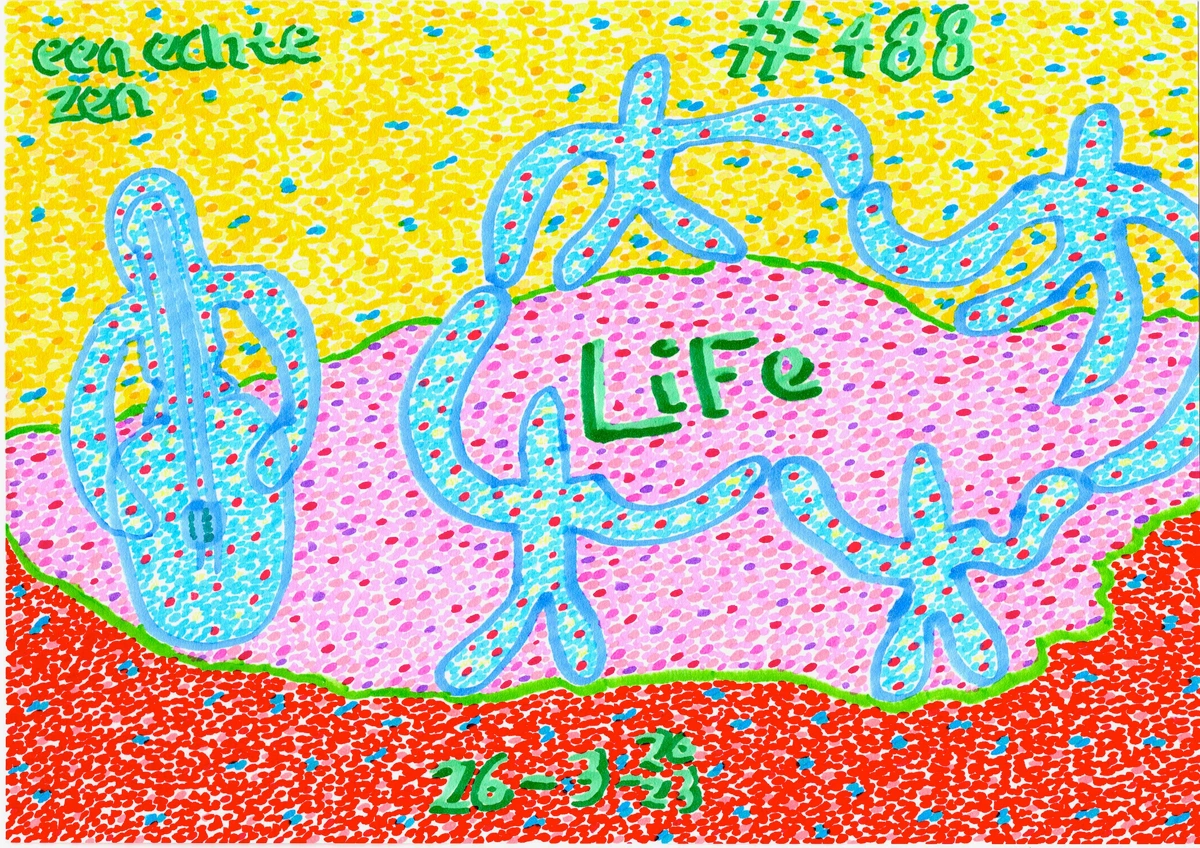

What is Folk Art? Authentic Charm, Enduring Spirit & Global Traditions | Zenmuseum.com

Unpack folk art's profound charm: its community roots, self-taught creators, utility, deep symbolism, and vibrant global traditions. Discover its living legacy, evolution, and how it inspires contemporary abstract art.

What is Folk Art? Unpacking Its Authentic Charm and Enduring Spirit, from Local Roots to Global Resonance

I've always found myself drawn to art that tells a story, something deeply, genuinely rooted in human experience, far beyond the polished walls of a high-brow gallery. I remember, clear as day, being a child and seeing my grandmother's handcrafted quilt — not just fabric, but a vibrant tapestry of family history, each stitch a quiet conversation with the past. That’s why Folk Art holds such a special place in my artistic heart. It’s like peeking into someone’s soul, a direct line to the traditions, beliefs, and daily lives of ordinary people. For me, it’s about the countless hands that must have touched that beautifully worn, hand-carved wooden bird I found in a small market in Mexico, the stories it silently held, not its perfection. This is art made not for critics or the marketplace, but because it needed to be made, a vibrant testament to the human spirit that often emerges from agrarian societies or close-knit communities, reflecting their unique worldviews and preserving rich oral traditions.

When you truly grasp what folk art is – its humble origins woven from necessity and oral traditions, its profound characteristics, and its diverse global presence – you begin to see why its authentic charm and enduring spirit continue to captivate us. This article will journey through the heart of folk art, exploring its roots, its vibrant characteristics, its global reach, and why it continues to resonate so deeply across generations and cultures, often serving as a powerful, tangible link to our shared human story. Let's begin by unraveling what truly constitutes this captivating art form.

The Heart of the Community: Defining Folk Art

Now, when you hear "folk art," you might picture anything from a quirky wooden bird carving to a beautifully woven blanket. And you wouldn't be wrong! It’s wonderfully diverse, spanning continents and centuries. But what really ties it all together? For me, it comes down to a few core ideas, a certain unpolished honesty that speaks volumes.

At its core, folk art is art created by self-taught artists, often within a specific community or cultural group, using traditional methods and materials. It’s born out of necessity, celebration, or spiritual belief, rather than formal training or commercial intent. Think of it as the visual language of a people, passed down through generations, often learned not in formal academies, but through observation, apprenticeship, and hands-on practice within the family or community itself. It's art that truly belongs to the people, by the people.

The Evolution of a Term: Understanding Vernacular Art

The term "folk art" itself gained prominence in the 19th and early 20th centuries, as art historians and collectors began to recognize the distinct aesthetic and cultural value of these traditionally made objects. Figures like John Cotton Dana, an American museum director, played a crucial role in championing what he called vernacular art – art that is indigenous to a particular place or group. This term emphasizes art made by and for a specific locale, often deeply ingrained in daily life and local practices. It's particularly useful because it highlights the embeddedness of the art within a regional culture, distinguishing it more sharply from the "fine art" produced by academic artists for elite audiences. This recognition was an acknowledgment that creativity wasn't confined to established institutions, often standing in contrast to early art criticism that dismissed such works as mere craft or decorative objects. Sometimes, related terms like "naive art" (art by self-taught individuals often characterized by a childlike simplicity) or even "art brut" (raw art, a broader category for outsider art) are used, but folk art specifically carries the weight of communal tradition, unlike the often solitary and idiosyncratic nature of naive or outsider art.

Historically, folk art often emerged from agrarian societies or close-knit communities, where cultural practices and skills were transmitted orally and through apprenticeship. Its origins are deeply intertwined with the daily lives, rituals, and collective identity of a people, reflecting their worldviews and aspirations through tangible forms. I've always been fascinated by how these seemingly simple objects could hold such profound meaning and serve as a record of a community’s soul, giving voice to countless untold stories that might otherwise be lost.

Folk Art vs. Fine Art: A Quick Glance

I often think about the different spaces these art forms inhabit. It’s not about one being “better” than the other, but recognizing their distinct purposes and origins. It's about appreciating what each brings to the vast world of human creativity. To crystallize these distinctions, let's look at this comparison:

Feature | Folk Art | Fine Art |

|---|---|---|

| Creator | Self-taught, learns within community, informal apprenticeship | Formally trained, academic institution, individual mastery |

| Purpose | Utility, cultural expression, storytelling; e.g., a decorated pot for daily use | Aesthetic contemplation, intellectual inquiry; e.g., a purely sculptural piece |

| Audience | Community members, everyday people | Elite patrons, collectors, institutions |

| Materials | Locally sourced, traditional, often humble | Often diverse, high-quality, professional, and experimental |

| Style | Traditional, often symbolic, direct, rooted in shared aesthetics | Varied, experimental, conceptual, individualistic |

| Focus | Preservation of tradition, collective identity | Innovation, individual expression, challenging norms |

| Innovation/Adaptation | Evolution through adaptation within tradition, slow changes | Often embraces radical innovation and paradigm shifts |

| Emotional Resonance | Direct, visceral connection to lived experience, communal history | Often intellectual, aesthetic, or conceptual contemplation |

As you can see, the contrast is stark. Folk art, in its very essence, is tied to its community – think of a beautifully woven basket made for carrying crops, its patterns conveying a family history and shared agrarian knowledge. Fine art, conversely, often pushes boundaries and explores individual vision, like a revolutionary abstract painting intended for a gallery. Each serves a vital, yet distinct, role in the tapestry of human expression.

Folk Art vs. Outsider Art: Unpacking the Nuances

This distinction can sometimes trip people up, myself included when I first started exploring these categories. While both often involve self-taught artists, their origins and intentions diverge significantly. Think of it this way: folk art is rooted in a community and its shared heritage, while outsider art is often born outside conventional artistic or societal norms, driven by an intense, individual vision. Consider Henry Darger, who created an entire, sprawling fictional world in secret, a prime example of an outsider artist. The overlap occurs where self-taught visionaries operate independently but their work eventually finds a communal audience or appreciation, often posthumously. The key here is the shared cultural context inherent in folk art, versus the deeply personal and often idiosyncratic world of outsider art.

Feature | Folk Art | Outsider Art |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | Embedded in community tradition/culture, shared heritage | Isolated, intensely personal vision, often without cultural precedent |

| Artist | Self-taught, learns within community, often anonymous initially | Self-taught, outside art world/society, driven by internal compulsion |

| Purpose | Reflects shared cultural identity/values, communal function | Driven by inner compulsion, personal world-building, often therapeutic |

| Style | Often traditional, shared aesthetic, recognizable forms | Highly unconventional, unique, idiosyncratic, raw, unfiltered |

| Materials | Traditional, local, specific to community, often humble | Often unconventional, found objects, diverse, whatever is available |

| Recognition | Recognized by community, later by art world, cultural significance | Discovered outside mainstream, often posthumously or by specific collectors |

| Audience/Community Interaction | Inherently for and by its community, shared understanding | May be created in isolation; audience often discovered later, often challenging |

Folk Art vs. Craft: More Than Just 'Handmade'

This can be a tricky distinction, and it's one I get asked about often! While all folk art inherently involves craft, not all craft qualifies as folk art. The key often lies in the intent, the context, and crucially, the transmission of knowledge within a specific cultural framework. The line, I've found, isn't always about the object itself, but the story behind its creation and its place in a community. It’s less about what is made, and more about why and how.

Craft is broadly defined by skill in making something, whether functional or decorative. It's about mastery of technique and production. If someone tells me they knitted a scarf after watching a YouTube tutorial, that's a lovely craft project. The maker’s personal skill is the primary driving force, and the knowledge is acquired individually. The term 'craft' itself has also evolved, sometimes elevated by contemporary artists who push the boundaries of traditional techniques into fine art contexts. Think of a ceramicist creating a beautiful, modern mug for commercial sale; it’s a craft object, skillfully made, but without a deep, inherited cultural narrative.

Folk art, however, always carries that cultural weight and connection to a specific group's heritage. It's a craft elevated by its communal purpose and its role in preserving cultural memory. Imagine that same beautifully knitted scarf, but this one uses traditional patterns passed down for generations within an indigenous community for ceremonial purposes, with each color and motif holding specific ancestral meaning. That's folk art. Or consider a simple, handcrafted wooden toy made for a child, admired for its artisan’s skill; that's craft. Now imagine a hand-carved ceremonial effigy, made using traditional joinery and adorned with specific symbols known only to a rural community, intended for a specific ritual to connect with ancestors – that's folk art. The difference isn't always in the object itself, but in the deeper cultural context and community narrative behind it. The transmission of knowledge through established community learning, rather than individual experimentation, is a crucial differentiator. It's the difference between making something beautiful and continuing a living story. It's about an object's 'biography' – how it came into being, who it serves, and what it represents for a collective. This distinction helps us understand why certain handmade objects are treasured as cultural heritage while others are simply admired for their skill.

The Unseen Threads: Key Characteristics of Folk Art

To truly appreciate folk art, I look for a few defining characteristics that weave through its global tapestry, much like recurring motifs in a cherished family quilt. These are the elements that, to me, make folk art so profoundly human, resonating with a universal desire to connect and create.

Foundational Elements:

- Community Roots: This is perhaps the most vital aspect. Folk art reflects the collective identity, values, and traditions of a specific group, whether it's a village, a religious community, or an ethnic diaspora. It’s art by and for a people, serving to bind the community, reinforce shared beliefs, and provide a tangible link to their heritage. It's about a shared history and present, beautifully articulated. I think of the vibrant kente cloth from Ghana, its intricate patterns speaking volumes about tribal history and social status, with specific weaves often reserved for royalty or special occasions. This deep communal connection is what distinguishes folk art from individual craft projects; it's a shared cultural expression.

- Self-Taught Artists & Generational Learning: The creators typically learn their skills through informal apprenticeship, by observing and imitating elders or peers in their community, or through generational transmission of knowledge. Formal art academies are almost entirely absent from their training path. It's about hands-on learning, a natural unfolding of skill, often starting from childhood. For instance, a potter might learn coiling techniques from their grandmother, not a university course, while a weaver might master complex patterns by watching and assisting community elders. This approach fosters a unique aesthetic deeply connected to tradition, often valuing ingenuity and resourcefulness over academic perfection. It's a continuous, living educational process.

Practical Aspects:

- Utility & Aesthetics Combined: Often, folk art pieces serve a practical purpose while simultaneously being beautiful. Think of a decorated pot for cooking, an embroidered textile used for clothing, a carved tool, or a painted furniture piece. The art isn't just on the object; it's part of its function, blurring the lines between daily life and artistic expression. I love how a functional object, like a beautifully crafted wooden spoon, can bring so much joy just by existing and being part of everyday rituals, elevating the mundane to the meaningful. It reminds us that art doesn't have to be sequestered in a gallery to profoundly impact our lives.

- Traditional Methods & Materials: Artists frequently use locally available, traditional materials and techniques. This could mean natural dyes extracted from local plants (imagine the earthy ochres, vibrant madder reds, or deep indigos!), specific types of clay dug from riverbeds, hand-carved woods like cedar, oak, or alder, specific fibers like alpaca wool for Andean textiles, natural pigments mixed from mineral earths, or even beeswax for traditional encaustic painting. The methods might include specific weaving patterns like those of Navajo blankets, regional carving styles like relief carving in Scandinavia, or traditional painting techniques passed down through families. It’s about working with what the earth provides, and what ancestors have taught, often inherently promoting sustainability through resourcefulness and minimal waste. As an artist, I deeply admire the ingenuity required to create such rich palettes from nature, and the sheer skill involved in mastering these age-old techniques. It's a profound connection to both nature and heritage.

Expressive Qualities:

- Symbolism & Storytelling: Folk art is incredibly rich with symbols and narratives. These can convey cultural stories, myths, historical events, religious beliefs, or personal experiences. For instance, animal motifs in Native American pottery often carry spiritual meanings, symbolizing connections to nature or specific tribal totems, while geometric patterns in Ukrainian embroidery (like the Vyshyvanka) can symbolize protection, fertility, or ancestral connections, with each color holding specific significance. The intricate patterns on a Ghanaian Adinkra cloth, for example, are visual proverbs and historical records, embodying generations of oral traditions. Mexican retablos use vivid colors and specific imagery to tell personal stories of miracles and gratitude, often incorporating found objects. In some African mask traditions, specific forms and materials are chosen not just for aesthetic appeal, but to embody ancestral spirits or convey complex social messages during ceremonial dances. Even the simple color palettes themselves can be symbolic, with certain hues reserved for mourning or celebration within a culture. Each stitch, each brushstroke, holds a deeper meaning, often communicating social commentary or collective beliefs in a subtle, enduring way. What stories do you think these symbols might tell, and how do they reflect the collective soul of a community? It’s a language understood deeply by its people.

- Unpretentious & Expressive: It values genuine, direct expression over academic perfection. The charm often lies in its directness, its unpolished sincerity, and a certain candidness that resonates deeply. It doesn't try to impress; it simply is. This raw honesty, for me, is often far more moving than any technically perfect piece. It reminds me of the pure impulse to create. This is a quality I actively strive for in my own abstract art, seeking that raw, honest impulse that bypasses overthinking and connects directly with the material, letting emotion guide the brush.

- Adaptation and Resilience: While deeply traditional, folk art is not static. It constantly adapts, reflecting new influences, materials, or changing social contexts while retaining its core identity. This ability to evolve ensures its survival and continued relevance, demonstrating a living, breathing tradition rather than a relic of the past. It’s a testament to how culture itself is a dynamic, ever-changing entity, finding new ways to express timeless truths.

A World in Every Brushstroke: Global Examples of Folk Art

Armed with these defining threads, let's now embark on a global journey to witness the incredible diversity and richness of folk art in action. Understanding these characteristics helps me, as an artist, truly appreciate the sheer variety and depth of folk art. When I travel, or even just browse through cultural museums, I’m always captivated by the diverse expressions of the human spirit. It's truly a global phenomenon. Here are a few examples that often pop into my mind, and perhaps they’ll spark your own curiosity:

Textile Arts: Woven Histories and Cultural Identity

From intricate Korean embroidered folding screens, often depicting symbols of longevity and prosperity like cranes and pine trees (embodying wishes for good fortune, often for weddings or important celebrations), to vibrant Guatemalan weavings with their rich cultural narratives woven into every thread, textiles tell stories of family, community, and belief. The patterns often carry generations of meaning, becoming wearable histories and embodying communal identity and symbolism. Think also of the stunning Navajo blankets, each design a unique story of the weaver and their world, often passed down through matriarchal lines. These blankets are not merely decorative; their intricate geometric patterns, created with natural dyes and specific weaving techniques (like the distinctive vertical loom method), often carry meanings related to cosmology, sacred mountains, and healing ceremonies. Examples like the intricate patterns of Ukrainian Vyshyvanka embroidery or the storytelling images found in Indian Kantha embroidery (where discarded saris are stitched together to tell stories of village life and mythology) highlight the diversity and depth of narrative within textile folk art. It's a testament to the idea that clothing and decor can be profound historical documents, holding within their fibers the very heartbeat of a culture.

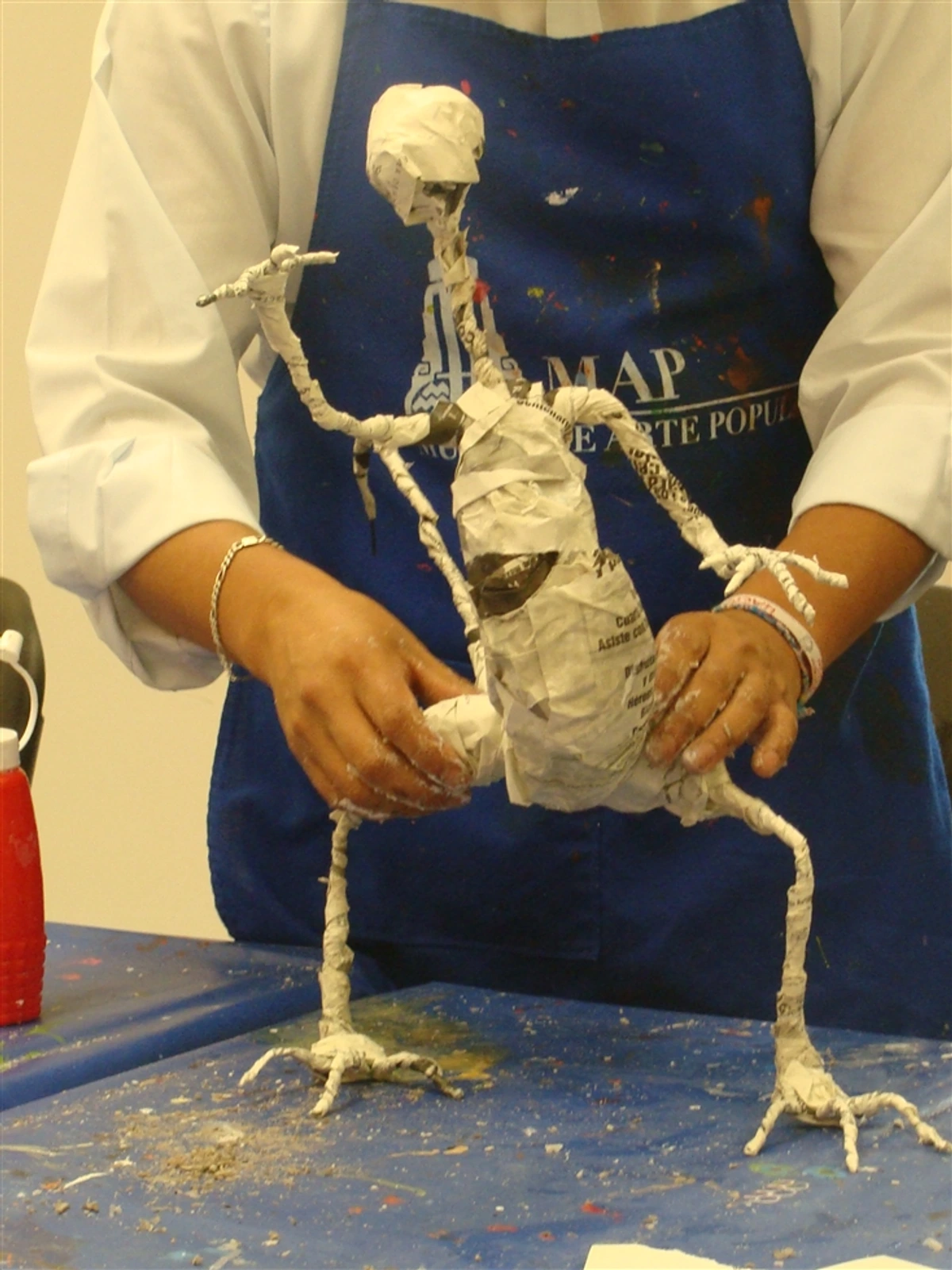

Wood Carvings: Sacred Forms and Everyday Tools

Consider the detailed animal carvings from Appalachia or the stunning religious effigies and katsina dolls from various Indigenous cultures, such as the Hopi. These pieces often carry deep spiritual, protective, or pedagogical significance, teaching lessons through their forms – the Katsina dolls, for instance, are not toys but educational tools to teach children about spirits and cultural values. The intricate Maori carvings (whakairo) from New Zealand, imbued with 'mana' (spiritual power, prestige, and ancestral authority), are profound examples, often adorning meeting houses (wharenui) or ceremonial tools. Their curvilinear designs and figures (tiki) are not just aesthetic; they depict ancestors and gods, literally embodying the living history and genealogy of a people, and are integral to rituals and communal narratives. In many European traditions, decorative elements like relief carvings on furniture or house gables also exemplify folk art, blending utility with symbolic expression – think of the elaborate Norwegian rosemaling found on wooden objects, originally a decorative painting style that incorporates stylized flowers and scrolls, passed down through families. I always marvel at how a piece of wood can hold so much meaning and history, becoming a tangible link to a community's soul and serving a function that ranges from the sacred to the everyday.

Ceramics & Pottery: Earth's Canvas

Decorated functional ware, like Mexican Talavera pottery with its distinctive blue and white motifs influenced by Moorish design and its intricate zellige tiles, or traditional European sgraffito bowls, blends utility with exquisite artistry, often reflecting local flora, fauna, or historical events. Talavera, specifically from Puebla, is a tin-glazed earthenware whose detailed production process (multiple firings, specific clays, and hand-painting) has been passed down for centuries, making each piece a testament to regional skill and history. Each piece is a canvas for local identity, with the texture of riverbed clay shaping its tactile presence. The vibrant slipware of the English countryside, adorned with simple yet charming patterns created by applying liquid clay (slip) before firing, also comes to mind, demonstrating how locally sourced materials and traditional techniques create distinct regional aesthetics. It's incredible to see the earth itself become the medium for such diverse expressions, transformed by human hands into objects of beauty and purpose, from the simplest vessel to the most elaborate tile.

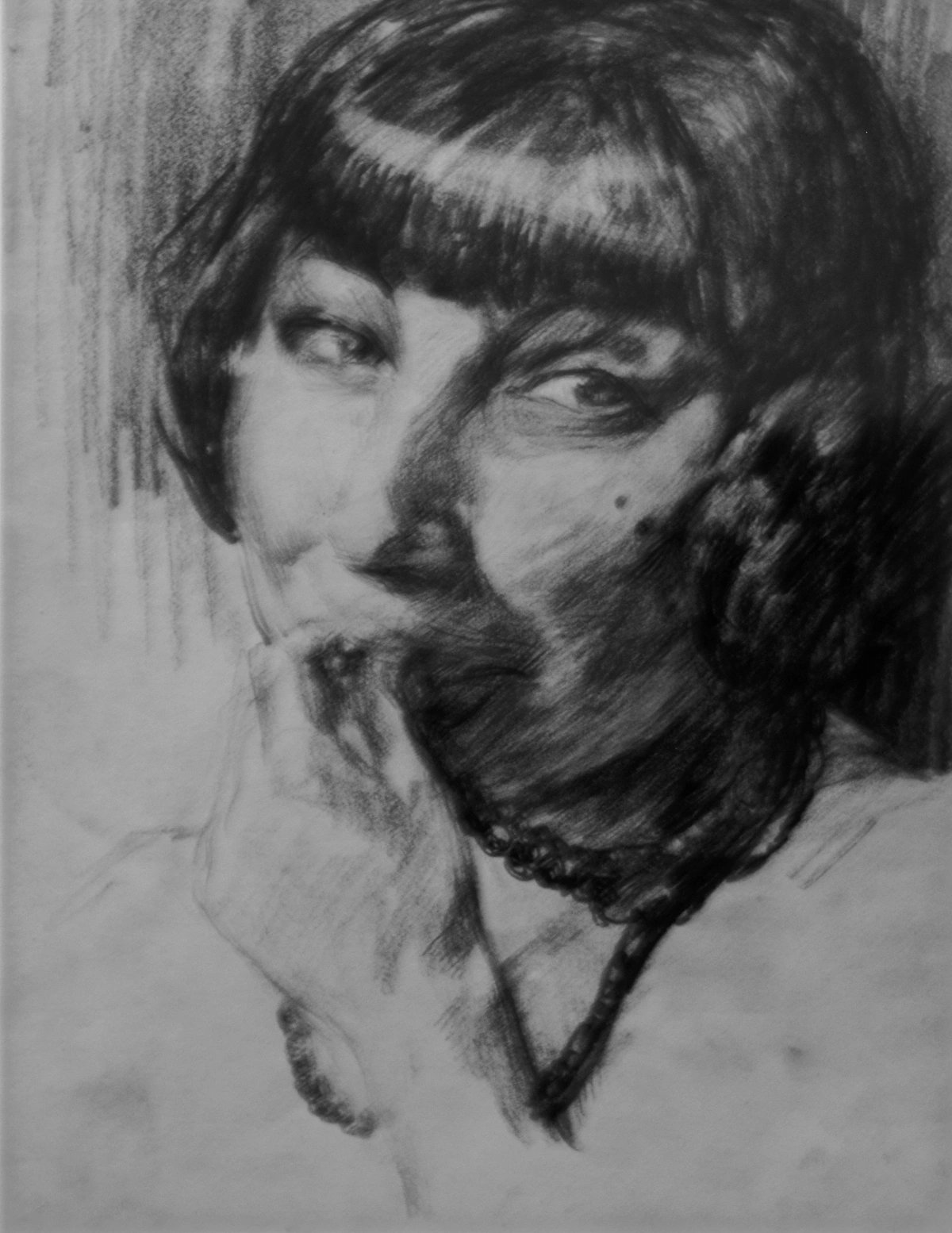

Painting & Illustration: Naive Visions and Sacred Narratives

While not always the first thing that comes to mind, naive paintings, often vibrant and narrative, certainly fall under this umbrella. Artists like Henri Rousseau or many anonymous painters whose works depict local scenes and celebrations embody this direct, untutored approach. Their lack of formal training often results in a refreshing honesty, similar to some outsider art in its directness. The Madhubani paintings from India, traditionally created by women using natural pigments to depict Hindu deities, auspicious symbols, and natural elements (like peacocks, fish, and elephants), are beautiful examples of this narrative folk painting, rich in symbolism and community lore, often passed from mother to daughter. The vibrant retablos of Mexico, small devotional paintings on tin, offer another powerful example, blending religious belief with personal storytelling and often incorporating found objects to give thanks for miracles. It’s art that feels like a window into another world, unburdened by academic rules, offering a pure, unfiltered glimpse into cultural beliefs and the everyday sacred.

Indigenous Art Forms: Living Histories and Spiritual Connections

Many indigenous artistic traditions, like Australian Aboriginal bark paintings, which are deeply connected to ancestral Dreamtime stories and the land (often mapping creation stories and sacred sites), Native American beadwork (used in both decorative and ceremonial contexts, with intricate patterns reflecting tribal identity and spiritual beliefs), or Maori carvings imbued with 'mana', are profound examples of folk art. They are rich with ancestral stories, spiritual connection to the land, and often serve crucial ceremonial or identity-affirming roles within their communities. For instance, many Indigenous Australian artworks serve as literal maps of sacred sites and ancestral journeys, used in ceremonies to transmit complex ecological and spiritual knowledge to younger generations. These traditions are not merely decorative; they are living histories and belief systems made manifest through intergenerational transmission of skills and knowledge, embodying a continuous conversation with ancestors and the earth itself. The beauty here is inextricably linked to cultural survival and identity.

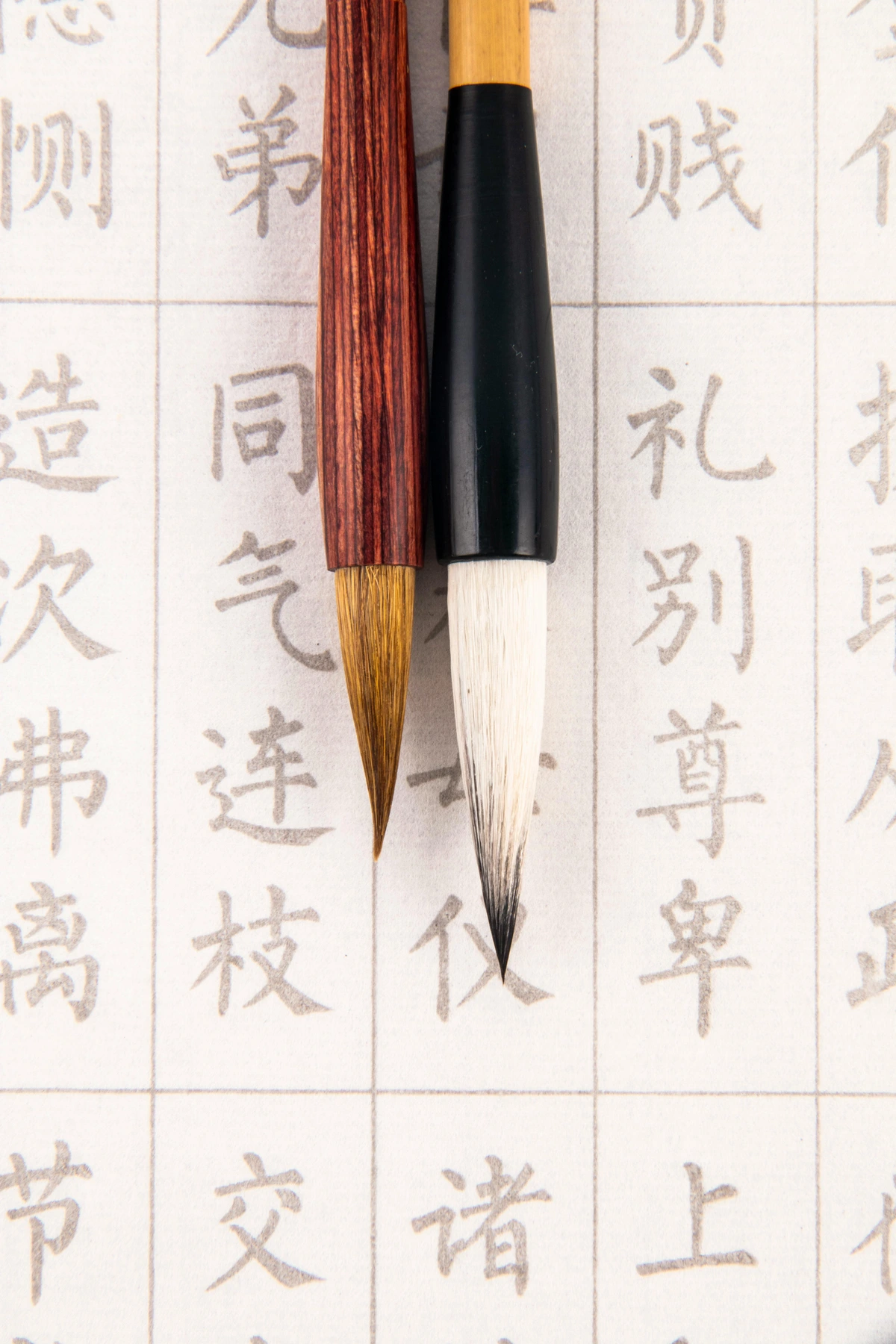

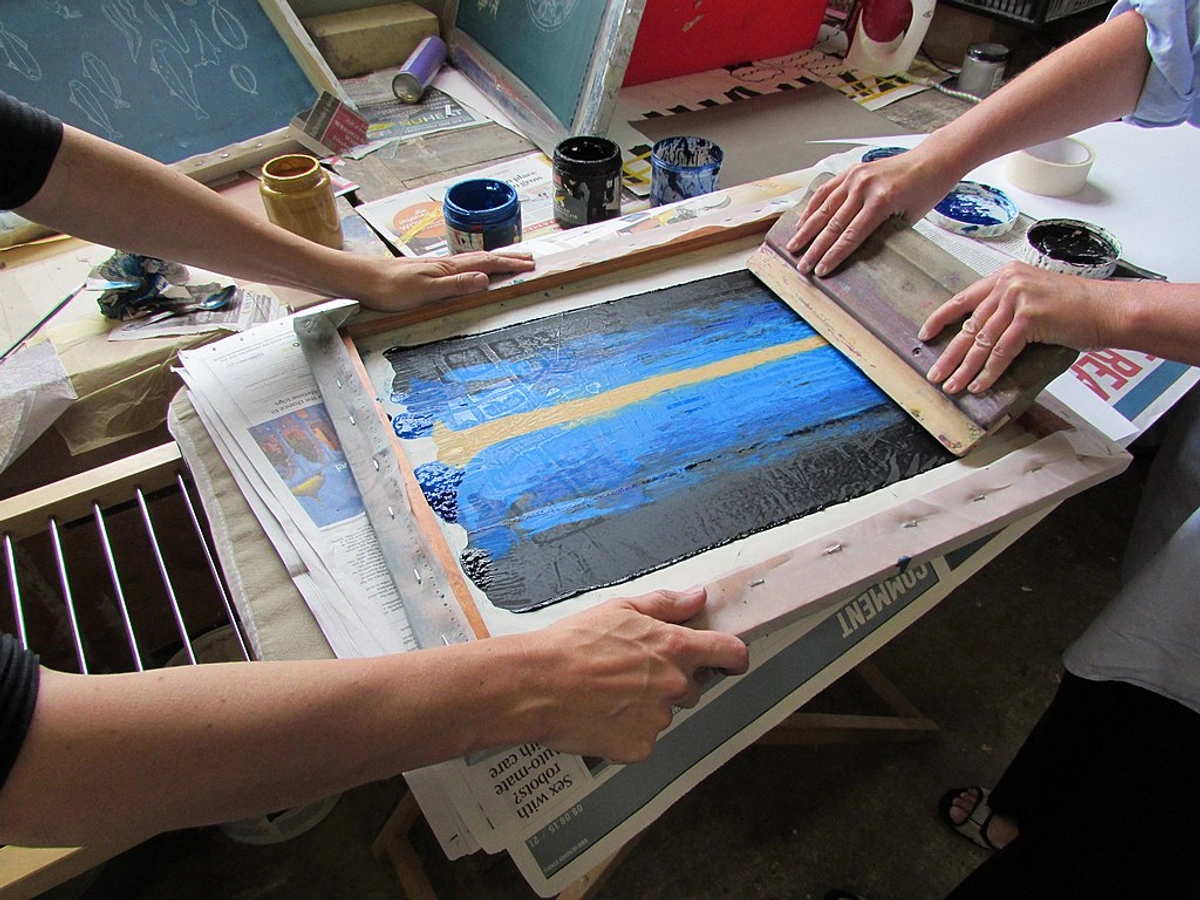

Printmaking: Democratizing Visual Culture

Early forms of woodcut and linocut printing, especially those used for popular imagery, religious tracts, or everyday announcements, were very much a part of folk art traditions, making art accessible to a wider audience. They democratized visual culture long before digital media, offering a way to disseminate shared stories and beliefs widely. Think of rudimentary broadsides, almanac illustrations, or ephemeral street art that once adorned European city walls, communicating everything from news to religious parables and even political satire. These prints often served practical functions: illustrating popular ballads, providing instructional diagrams, or documenting local events, bringing visual narratives directly to the common person. Japanese Ukiyo-e woodblock prints, while often produced by skilled artists, are strongly tied to folk art's spirit because they depicted popular subjects of everyday life – actors, courtesans, landscapes, and folk tales – making them widely accessible and an essential part of collective visual culture for the common person, embodying a popular, narrative approach to art. These forms, in their essence, are about sharing a visual story with many, empowering communities through visual communication.

Folk Art in Architecture and Design: Embellishing Everyday Spaces

While we often think of folk art as portable objects, its principles and aesthetics frequently extend into vernacular architecture and interior design, transforming mere structures into cultural statements. Think of the brightly painted facades of houses in traditional villages (like those with intricate geometric patterns in parts of Eastern Europe, where specific colors and motifs can denote family status or offer protection), the intricate wrought ironwork on balconies in Spanish colonial towns (each scroll a testament to local craftsmanship), or the decorative motifs carved into furniture that reflect local cultural identity and storytelling. It's about infusing everyday spaces with beauty and meaning, crafted with local materials and techniques, such as the elaborate rosemaling found on wooden objects and interiors in Norway, or the intricate tile mosaics (like Moorish zellige) adorning buildings in North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula. These environments aren't just built; they're woven with cultural narratives and a deep sense of place, creating a living canvas where daily life unfolds. Which of these traditions sparks your curiosity the most? Take a moment to imagine the stories they hold, not just in an object, but in an entire lived environment!

The Living Legacy: Preservation and Evolution in a Changing World

Folk art isn't just a relic of the past; it's a living, breathing tradition that plays a crucial role in society today, a constant dialogue between the old and the new. But how does this vibrant heritage survive and evolve in our rapidly shifting global landscape? It’s a question of resilience and adaptation.

Folk Art as a Repository of Cultural Memory and Identity

I see folk art as a magnificent cultural time capsule. Each piece, from a carved mask to an embroidered garment, acts as a repository of knowledge, beliefs, and history for a community. Its practice contributes directly to the continuity of traditions, ensuring that skills, stories, and cultural identities are passed down from one generation to the next. For many communities, particularly marginalized or indigenous groups, folk art is a powerful tool for maintaining and asserting cultural identity in the face of external pressures, often serving as a quiet, enduring protest against assimilation by preserving language, distinct visual identities, and traditional practices that dominant cultures might try to erase. It also holds immense historical significance, shaping national identities and providing invaluable visual records of societal changes across various countries. It fosters a sense of belonging and social cohesion, proving that art can be a form of profound resilience. It’s a tangible link to human history, offering vital lessons about adaptation, communal values, and diverse worldviews for contemporary society.

Challenges in Preservation: Threats to a Living Heritage

In a rapidly changing world, folk art faces significant challenges. Economic pressures often force artisans to abandon traditional practices for more lucrative work, leading to a loss of skills and knowledge – imagine a skilled weaver choosing factory work over the loom to feed their family, or a community's unique pottery technique disappearing because younger generations are no longer taught it due to a lack of perceived economic viability. The rise of mass production, offering cheaper alternatives, also diminishes the market for handmade folk art. Furthermore, cultural assimilation and globalization can dilute unique traditions as younger generations move away from ancestral practices, sometimes seeing them as "old-fashioned" or irrelevant in a modern context. Even climate change, I've observed, can impact the availability of traditional materials, forcing difficult adaptations. Organizations like the Folk Art Alliance and UNESCO's Living Heritage programs actively work to identify, preserve, and promote these invaluable traditions, often through documentation, training, and market support, battling against these powerful forces of change. It's a continuous struggle to maintain authenticity in a world of accelerating homogenization.

The Role of Institutions and Patrons

Beyond individual communities, museums, galleries, and private collectors have played a vital role in recognizing and preserving folk art. Early collectors, much like John Cotton Dana, helped elevate folk art from mere craft to a recognized art form. Today, institutions often provide platforms for folk artists, offering educational programs, exhibitions, and vital economic support. However, this interaction also presents challenges, such as the potential for commercialization to alter traditional forms, leading to a debate around "authenticity" versus "art market value." There's also the ethical complexities of acquiring pieces from vulnerable communities, and the risk of "ghettoization" where folk art is primarily displayed separately from fine art, rather than integrated into broader art historical narratives. This is why I always try to consider the journey a piece has taken and its provenance, aiming to preserve without commodifying excessively. It's a delicate balance, indeed, ensuring that preservation doesn't inadvertently lead to exploitation.

Contemporary Folk Art: Adapting Traditions for a New Era

It’s fascinating to observe how folk art evolves. While it's deeply traditional, contemporary folk artists aren't necessarily confined to their local villages anymore. They continue to create, often adapting ancestral techniques to modern aesthetics or integrating their traditional crafts into contemporary design. This shows a beautiful fluidity in creativity, demonstrating how a tradition can remain vibrant by responding to the present without losing its soul. We see traditional weaving patterns appearing in modern fashion, or ancient carving techniques used to create conceptual installations and contemporary sculptures by indigenous artists, like the contemporary Kwakwakaʼwakw totem poles that blend traditional form with contemporary social commentary. It's a quiet revolution of tradition, showing how deep roots can still sprout new branches, continually expressing relevant meanings for a new generation.

Folk Art in the Digital Age: Opportunities and Challenges

The digital age has opened up new avenues for sharing, offering both opportunities and challenges. Artists can now use online platforms to reach wider audiences, showcasing their traditional crafts and stories to a global market and finding new patrons. This can provide much-needed economic viability and even facilitate digital archiving of techniques for future generations, like 3D scanning objects or creating virtual libraries of traditional patterns. While I'm personally a bit skeptical of fads like NFTs and blockchain for truly appreciating art – I mean, how can a digital token truly capture the tangible history, tactile essence, and communal spirit of a hand-woven basket or a carved effigy? – the inherent value of folk art — its authenticity, its craftsmanship, its story — shines through regardless of how it's presented online. The real art is in the object, not its digital wrapper. The challenge, of course, is balancing this global exposure with preserving the integrity and local context of these traditions, ensuring fair compensation, and preventing cultural appropriation. It's a new frontier, full of promise and pitfalls, demanding careful navigation to ensure technology serves the art, not the other way around.

Why Folk Art Speaks to My Soul (and Might Speak to Yours)

After exploring the profound depth of folk art, it's clear why this art form resonates so deeply with me as an artist. There's a raw honesty in folk art that I find incredibly inspiring. As an artist working often in abstract forms, I sometimes find myself a little too caught up in theoretical concepts or formal concerns. Folk art reminds me of the pure joy of creation, the direct connection between hand and material, and the power of art to communicate without needing a lengthy explanation. It's almost a therapeutic reminder to just make, to get back to the basics, to connect with the material directly, like a conversation between my hands and the canvas, letting the intuition guide the brush.

Even in my own abstract art, where precise representation isn't the goal, the directness and intentionality of folk art reminds me of the raw impulse to communicate emotion and story. The bold, symbolic use of color in traditional folk textiles, for instance, often directly inspires my palette choices in many of my vibrant prints, aiming for that same impactful, immediate emotional resonance. I find that the rhythmic, layered patterns of a ceremonial Aboriginal bark painting, or the stark, impactful symbolism in a West African mask, often echo in the structure and emotional weight of my own abstract figures artwork. I often see echoes of folk art's fundamental design principles – its repetitive patterns, symbolic motifs, and bold color choices – in the vibrant energy of many expressionist works or even the geometric purity of cubist and minimalist art. Artists like Paul Gauguin were famously inspired by non-Western and folk art forms, seeking a raw, authentic expression that transcended academic conventions. It’s a testament to human ingenuity and the universal drive to create beauty and meaning in our lives. It shows that art isn't just for museums (though many folk art pieces now rightly grace those halls!), but it’s an integral part of living, breathing culture, a constant source of inspiration.

It makes me think about my own creative journey and how I can infuse more of that genuine, unpretentious spirit into my own work, whether it’s a vibrant print of abstract birds or an original painting I’m working on in my studio (you can sometimes see glimpses of that journey on my /timeline page!). If you're looking for art that embodies this spirit, you might find something that speaks to you in my collection available to /buy.

Finding True Echoes: Appreciating & Collecting Folk Art

As someone who cherishes authentic expression, I find the appreciation and even collection of folk art incredibly rewarding. But what makes a piece truly valuable, and how do you navigate the market for genuine articles in a world increasingly filled with mass-produced imitations? It’s a bit like being an art detective, but with heart and integrity.

The Layers of Value:

- Value Beyond Price: The value of folk art often goes far beyond its monetary cost. It lies in its story, its cultural significance, its unique craftsmanship, and its ability to connect you to a different way of life. An authentic piece carries the weight of generations, a tangible echo of human history, offering deep personal connection and emotional resonance. It’s an investment in a piece of living heritage, a shared human narrative, and a direct link to the ingenuity of common people.

- Identifying Authenticity: This is where research and reputable sources come in. Look for clear provenance – the history of ownership and creation. Genuine folk art is typically made from traditional, local materials and exhibits the characteristic styles and maker's marks of a specific region or community. But beyond that, look for the subtle imperfections that speak to manual creation, the wear patterns indicative of true age and use, and specific regional stylistic markers that aren't easily replicated. Avoid pieces that seem mass-produced, too perfect, or lack that unique, 'handmade' quality. Talking to local artisans and cultural experts is invaluable. Moreover, be mindful of ethical considerations, especially when collecting indigenous art; ensure it is acquired respectfully and benefits the communities from which it originates, understanding the object's original purpose and meaning, and ideally, supporting fair trade initiatives. I always try to consider the journey a piece has taken, not just its current market value. It's about respecting the art and the artist.

- Joys and Challenges: Collecting folk art is a journey of discovery. The joy comes from unearthing unique pieces, learning their stories, and supporting traditional artisans directly and ethically, often through fair trade initiatives. The challenge can be identifying truly authentic pieces in a world full of replicas, but with diligence and a genuine appreciation for the stories behind the art, it's an incredibly enriching experience. It connects you directly to the heartbeat of humanity, a tangible link to our collective past and present, enriching your own understanding of diverse cultures.

Further Reading & Resources

For those of you who, like me, find yourselves captivated by the enduring spirit of folk art and wish to dive deeper, here are some invaluable resources and institutions that continue to champion its preservation and understanding:

- The Folk Art Alliance: A fantastic organization dedicated to supporting folk artists and promoting the appreciation of folk art through education and advocacy. They offer grants and market opportunities.

- UNESCO's Living Heritage Programs: Their initiatives around Intangible Cultural Heritage offer a global perspective on preserving traditional knowledge and practices, including many folk art forms, often focusing on the processes and skills behind the art.

- International Folk Art Market, Santa Fe: One of the largest markets of its kind, offering direct support to artisans from around the world and a chance to experience the global tapestry of folk art firsthand, promoting fair trade.

- Specific Museum Collections: Many museums worldwide have dedicated folk art collections (e.g., American Folk Art Museum in NYC, International Folk Art Museum in Santa Fe) which are treasure troves of information and inspiration, often showcasing regional specialties.

- Academic Texts: Scholars like Henry Glassie, John Michael Vlach, and Robert Farris Thompson have written extensively on folk art, providing deep insights into its cultural significance and history, offering rigorous methodological approaches to its study.

Frequently Asked Questions About Folk Art

These are the questions that often pop up when I chat with people about folk art, and I'm happy to shed some light on them:

Q: Is folk art always old?

A: Not at all! While many historical examples exist, folk art is a living tradition. Contemporary folk artists continue to create today, often integrating modern themes with traditional techniques, ensuring the art form evolves while retaining its core spirit. It’s a dynamic, ongoing conversation between past and present, much like how language itself evolves. You can find vibrant folk art being made in communities around the world right now, proving its timeless relevance and ongoing cultural significance.

Q: Can folk art be abstract?

A: Generally, folk art is more narrative and representational, focusing on familiar subjects, symbols, or stories within a community. However, abstract elements might appear in decorative patterns or motifs, particularly in textiles or ceramics where geometric designs often carry deep symbolic meaning and can be quite visually abstract in their composition. True abstract art, as we often define it today (think the definitive guide to understanding abstract art from cubism to contemporary expression), typically stems from different art historical movements and intentions than traditional folk art. Yet, as I mentioned, I often find myself seeing folk art's inherent design principles and raw expressiveness echo in later movements, like the rhythmic patterns in cubist art or the stark simplicity of minimalist works. It shows how fundamental visual language transcends categories, even if the intent differs.

Q: What's the difference between folk art and craft?

A: This is a nuanced point! As I mentioned earlier, all folk art involves craft, but not all craft is folk art. Craft can be purely functional or decorative without necessarily having deep cultural roots or community identity. Folk art, however, always carries that cultural weight and connection to a specific group's heritage, reflecting its traditions and collective memory. The key difference often lies in the transmission of knowledge – folk art is typically passed down through established community learning and tradition, while craft might be learned from books, online tutorials, or individual experimentation without that specific cultural lineage. It's the depth of cultural connection and communal purpose that elevates craft to folk art, making it a living document of a people's story, imbued with collective meaning.

Q: How can I identify authentic folk art versus reproductions or mass-produced imitations?

A: This is crucial! To identify authentic folk art, look for clear provenance – the history of who made it and where it came from. Genuine pieces are typically made from traditional, local materials and exhibit characteristic styles or maker’s marks of a specific region. Look for subtle imperfections that reveal manual creation, wear patterns suggesting genuine age and use, and specific regional stylistic markers not easily replicated. Authentic folk art often carries a unique, handmade quality. Be wary of items that appear too perfect, factory-made, or overly commercialized. Engaging with local artisans, cultural experts, and reputable dealers is invaluable. Always prioritize ethical acquisition, especially for indigenous works, to ensure communities benefit and cultural integrity is respected.

Q: How does folk art differ from regional or ethnic art?

A: This is an excellent question, and the terms often overlap! While folk art is almost always regional or ethnic in its origin, the term 'folk art' specifically emphasizes the community-based, self-taught, and tradition-bound nature of its creation. Regional or ethnic art is a broader category that can include 'fine art' created by formally trained artists within a specific region or ethnic group. So, all folk art is regional/ethnic, but not all regional/ethnic art is folk art. Folk art focuses on the shared, everyday practices and cultural expressions of a common people, often distinct from academic or elite artistic traditions, regardless of the region. It's about the everyday art of a specific cultural group, rather than a broad geographical or ethnic designation that could encompass any style or origin.

The Enduring Heartbeat: Why Folk Art Matters

Ultimately, folk art is more than just beautiful objects; it's a testament to human resilience, creativity, and the enduring power of community. It’s a reminder that art can emerge from anywhere, created by anyone, for reasons as diverse as human experience itself. From the intricate patterns of a traditional textile to the humble carving made for daily use, folk art embodies the stories, beliefs, and soul of a people. It's a living heritage that constantly adapts, teaching us about our shared past and guiding us towards a more interconnected future. For me, it serves as a powerful anchor, a reminder to stay authentic and connected to the deeper impulses of creation, a lesson I carry into my own work every single day, as I try to infuse my own abstract art with that same raw, honest spirit. It's a conversation across time and cultures, a heartbeat echoing through generations, and one I hope you'll continue to explore and cherish, finding your own connections to its profound authenticity. It truly is the art of our collective humanity.