Contrapposto Explained: From Ancient Grace to Modern Art's Dynamic Pulse

Dive deep into contrapposto: what it is, its origins in Greek & Roman sculpture, its Renaissance revival, and how this dynamic pose profoundly shaped the representation of the human form, influencing even abstract art today.

Contrapposto in Sculpture: My Personal Journey Through Art's Dynamic Pose and Enduring Legacy

I confess, art history terms used to make my eyes glaze over faster than a glazed donut disappearing at a family gathering. But then, every now and then, one would stick. Contrapposto was one of those. It sounds fancy, doesn't it? Perhaps like a secret handshake among art connoisseurs or a particularly delightful Italian dessert, almost making it feel off-limits. But trust me, once you "get" it, you start seeing its ghost everywhere. Not just in museums, but in the way someone leans casually against a wall, or how a dancer pauses mid-movement. It’s a fundamental shift in how we represent the human form, and it's surprisingly personal once you start looking. In this article, we'll explore what it is, why it was a game-changer, and how its echoes, or even its deliberate rejection, resonate in today's art world – from classical masterpieces to my own abstract explorations.

What Even IS Contrapposto? Breaking Down the Dynamic Shift

So, what are we talking about here? In the simplest terms, contrapposto (pronounced con-tra-PO-sto) refers to a human figure standing with most of its weight on one leg, causing its shoulders and arms to twist off-axis from its hips and legs. Think of it as the ultimate relaxed, natural pose.

Imagine you're just standing, chilling out. Your weight naturally shifts. One leg becomes the sturdy anchor, bearing your weight. The other leg relaxes, perhaps bending slightly or stepping forward. This shift causes a beautiful, subtle chain reaction through the body: the hip on the weight-bearing side rises, while the hip on the relaxed side drops. Conversely, the shoulder on the weight-bearing side drops, and the shoulder on the relaxed side rises. This opposing tilt of the hips and shoulders is what creates that natural, graceful "S" curve through the torso, giving the figure a dynamic twist and a palpable sense of potential movement. It’s the opposite of stiff, front-facing formality, which often implies a static, almost lifeless presentation. It's life breathed into stone.

Before contrapposto, many sculptures (especially ancient Egyptian and archaic Greek ones like the rigid, almost block-like Kouros and Kore figures) often looked a bit... well, like they'd swallowed a broomstick. These early forms, while possessing their own solemn beauty – a stoic, timeless quality – were fundamentally symmetrical and frontal, presenting a figure as a static block rather than a living being. There's a certain charm to that, absolutely, but it doesn't quite capture the messy, wonderful dynamism of a living, breathing person, caught mid-thought. Artists eventually sought to move beyond this, aiming for a more believable, more human presence.

A Brief Jaunt Through History (No Maps Needed)

So, that's the mechanics of it. But how did this revolutionary idea come to be? Well, like many of art's great innovations, contrapposto isn't just a static pose; it has its own rich history within sculpture, unfolding through centuries and artistic movements, and even includes a bit of a dramatic comeback.

The Greek & Roman Origins: Unlocking the Secrets

The ancient Greeks were the true pioneers, famously unlocking the secrets of naturalistic representation. Sculptors like Polykleitos, with his Doryphoros (Spear Bearer), perfected the technique around the 5th century BCE. Polykleitos even developed a Canon of Proportions, a mathematical formula for the ideal human form, which inherently favored the dynamic balance of contrapposto. I've always found it incredible how they moved from the stiff, frontal poses of the earlier Kouros and Kore figures to something so dynamically naturalistic, giving their gods and heroes a grounded, yet ethereal, quality. The Romans, ever practical, loved it too and copied many Greek masterpieces – oh, imagine the sheer volume of artistic cross-pollination! – spreading the contrapposto gospel far and wide. Honestly, I picture Roman workshops churning out these graceful figures like a modern-day factory, saying, "Another heroic contrapposto? Right away!" For a while, it was the way to depict ideal human beauty and athletic prowess.

However, with the fall of Rome and the rise of new cultural values, this dynamic approach to the human form would largely recede, making way for different artistic priorities during the Middle Ages.

The Renaissance Revival: A Roaring Comeback

Then came the Middle Ages, and for various reasons (the Church, for example, often prioritized spiritual concerns over overt anatomical realism, viewing the naturalistic nude as potentially promoting sensuality rather than piety), contrapposto largely fell out of favor. Figures became more stylized, less concerned with anatomical accuracy. I sometimes wonder if the Middle Ages offered a necessary respite from the relentless pursuit of classical perfection, a chance for art to explore different avenues of symbolism and divine abstraction, before the grand resurgence. But oh, how it roared back during the Renaissance! Artists, looking back to classical antiquity for inspiration – often through the study of rediscovered Roman copies of Greek masterpieces – rediscovered contrapposto with gusto. Donatello's David (the bronze one, the first free-standing nude since antiquity) is a prime example, oozing with youthful contrapposto charm, as is his St. George, standing heroically with a clear weight shift.

And Michelangelo's David? Seeing it for the first time, I remember feeling a shiver down my spine. The sheer size, yes, but the way his weight shifts from his right leg, causing his hip to dip and his powerful shoulders to turn ever so slightly in defiance – it's an absolute masterclass in capturing potential movement and internal resolve.

This era really was the ultimate guide to Renaissance sculpture, and contrapposto was a huge part of it, influencing not just sculpture but also the way painters like Raphael (think of the dynamic figures in his School of Athens) and Leonardo da Vinci depicted figures in their masterpieces, bringing a palpable sense of life and realism to the canvas.

The Baroque: Drama, Emotion, and Exaggeration

Just when you thought contrapposto had settled into its dignified classical form, the Baroque period (roughly 17th century) came along and said, 'Hold my beer!' Baroque artists, fueled by a desire for heightened emotion, drama, and theatricality, took the subtle dynamism of contrapposto and cranked it up to eleven. Think Bernini's David (yes, another David!), caught mid-action, muscles coiled, body twisted in an intensely dramatic contrapposto that practically leaps off its pedestal. It's less about serene balance and more about explosive movement and emotional intensity. While the Renaissance saw a rediscovery of contrapposto for its naturalism, the Baroque embraced it as a tool for storytelling, creating figures that truly performed their narratives, engaging the viewer with an almost cinematic dynamism. It's a reminder that even foundational artistic principles can be reinterpreted to serve new cultural and aesthetic purposes – a concept I think about often in my own work.

Why It Matters: Breathing Life into Stone (and Canvas!)

When the ancient Greeks truly mastered contrapposto, it was revolutionary. It wasn't just about making statues look "nicer" or more anatomically correct; it was about imbuing them with a sense of movement, palpable emotion, and a profound psychological depth that had largely been missing. Suddenly, figures weren't just standing; they were in the act of standing, caught in a fleeting moment, suggesting an inner life, a complex thought process, a burgeoning feeling. This could convey anything from serene confidence, quiet contemplation, and stoic resolve to anxious anticipation or defiant struggle. It allowed artists to tell more engaging stories, as figures could interact with their environment and each other more naturally, their bodily language speaking volumes about their internal state or moral character.

It's like the difference between a posed school photo where everyone's perfectly straight and a candid shot where someone is mid-laugh, head tilted, weight shifted. Which one feels more human? Exactly. This principle is a cornerstone in understanding the elements of sculpture itself, laying the groundwork for much of what followed in Western art. It makes us, the viewers, feel a connection, an empathy, because we recognize that subtle, familiar shift in our own bodies. It's profound how a subtle hip tilt can bridge centuries, connecting us to an ancient ideal of humanity. Next time you're wandering through a museum (or perhaps considering a visit to our own museum in 's-Hertogenbosch), pause before a figure, look for that tell-tale weight shift, and you might just feel that connection yourself.

Feeling the Flow: Characteristics of Contrapposto

When I look at a figure in contrapposto, I always try to spot these subtle (and sometimes not-so-subtle) cues, almost like a game of artistic "I Spy." It's fascinating how artists intentionally manipulate these elements to achieve specific effects, from serene grace to defiant tension:

- The Weight-Bearing Leg: One leg is straight, firmly planted, bearing the figure's weight. It’s the anchor, often showing a subtle tension.

- The Relaxed Leg: The other leg is bent, relaxed, maybe slightly forward or to the side, ready to move. This leg feels lighter, freer.

- Hip Tilt: The hip on the side of the relaxed leg will usually be lower than the hip on the weight-bearing leg.

- Shoulder Tilt: Conversely, the shoulder on the side of the relaxed leg will often be higher than the shoulder on the weight-bearing side. This opposing tilt of the hips and shoulders is what truly creates that beautiful, natural "S" curve through the torso, giving the figure a dynamic twist.

- Head Tilt: Sometimes, the head will tilt in the opposite direction of the shoulders, adding even more dynamism and suggesting a moment of thought or engagement.

- Psychological Depth: All these subtle shifts contribute to a figure that feels more human, more thoughtful, less like an inanimate object and more like someone caught mid-thought, perhaps conveying anything from serene confidence to introspective vulnerability, or even a sense of impending action.

Beyond the Classical: Contrapposto's Echoes (or Absence) Today

So, that's contrapposto in its classical glory, largely a Western art phenomenon, though other cultures developed their own sophisticated ways of depicting the human form without necessarily employing this specific weight shift. But what about now, especially in my own corner of the art world? My work, for example, is often abstract, full of vibrant colors and bold lines. You won't find a lot of realistic human figures, let alone classical contrapposto, in my art. And that's okay! It's a different conversation.

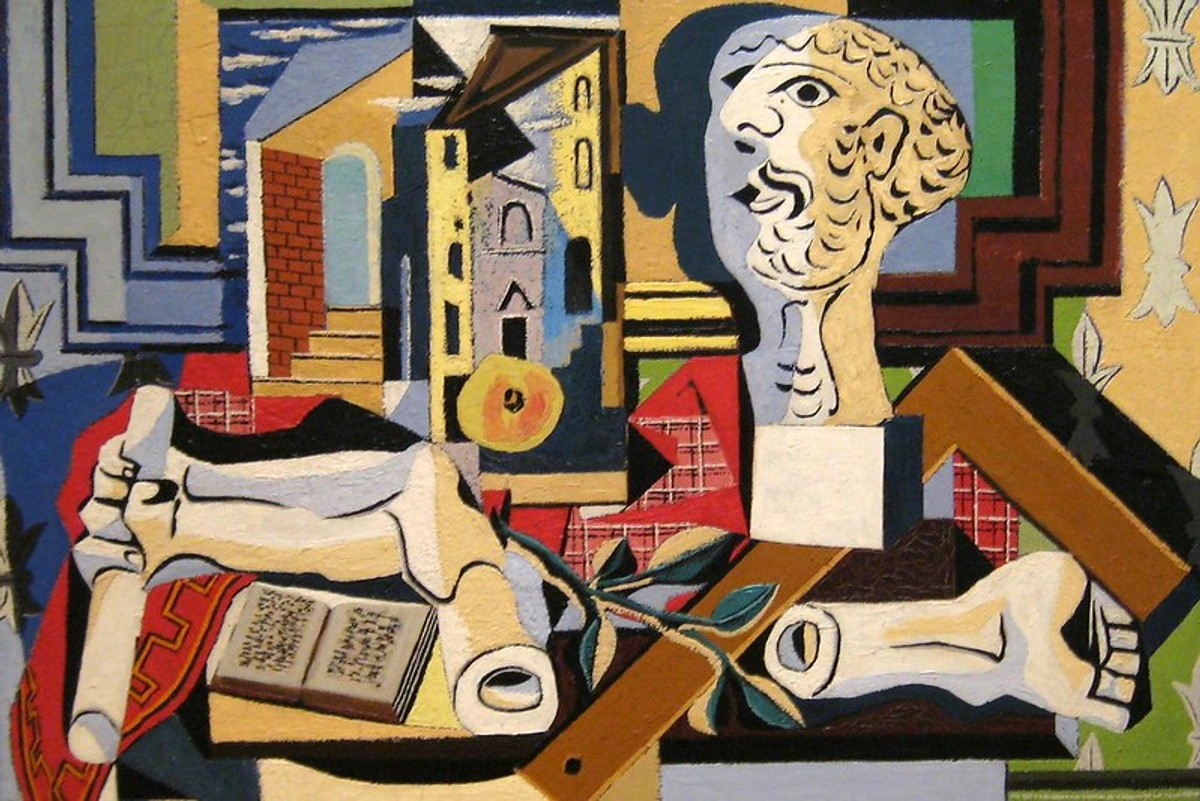

Modern and contemporary art has had a long, fascinating journey away from strict realism and classical ideals. Artists challenged everything, from subject matter to form, to the very materials and techniques of sculpture used. The advent of photography, for instance, arguably freed artists from the imperative of pure mimetic representation, allowing them to explore other dimensions of human experience and perception. Think Cubism, where figures are fractured and reassembled, deliberately rejecting naturalistic representation to explore multiple perspectives simultaneously and delve into abstract intellectual ideas rather than physical realism. If you want to dive deeper into this fascinating period, check out our ultimate guide to Cubism – it's quite a mind-bending ride.

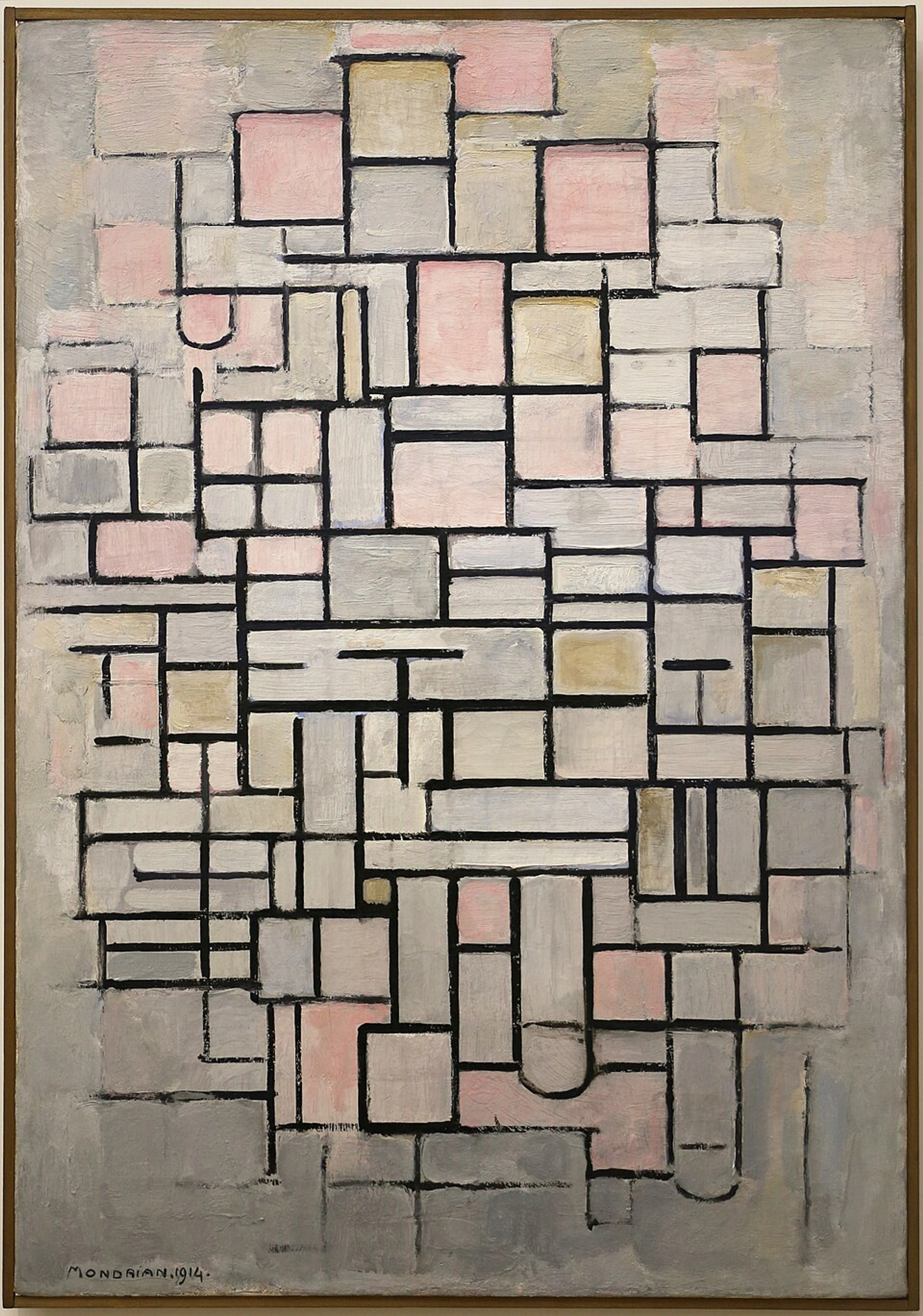

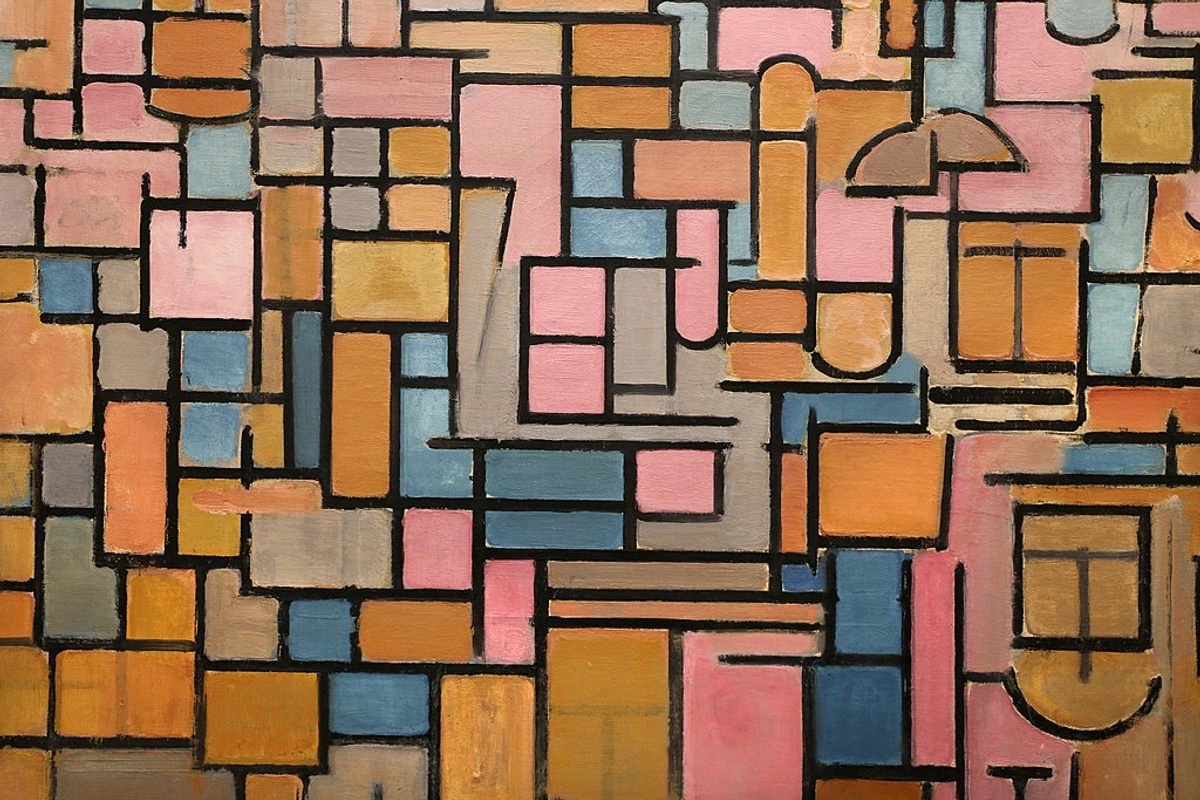

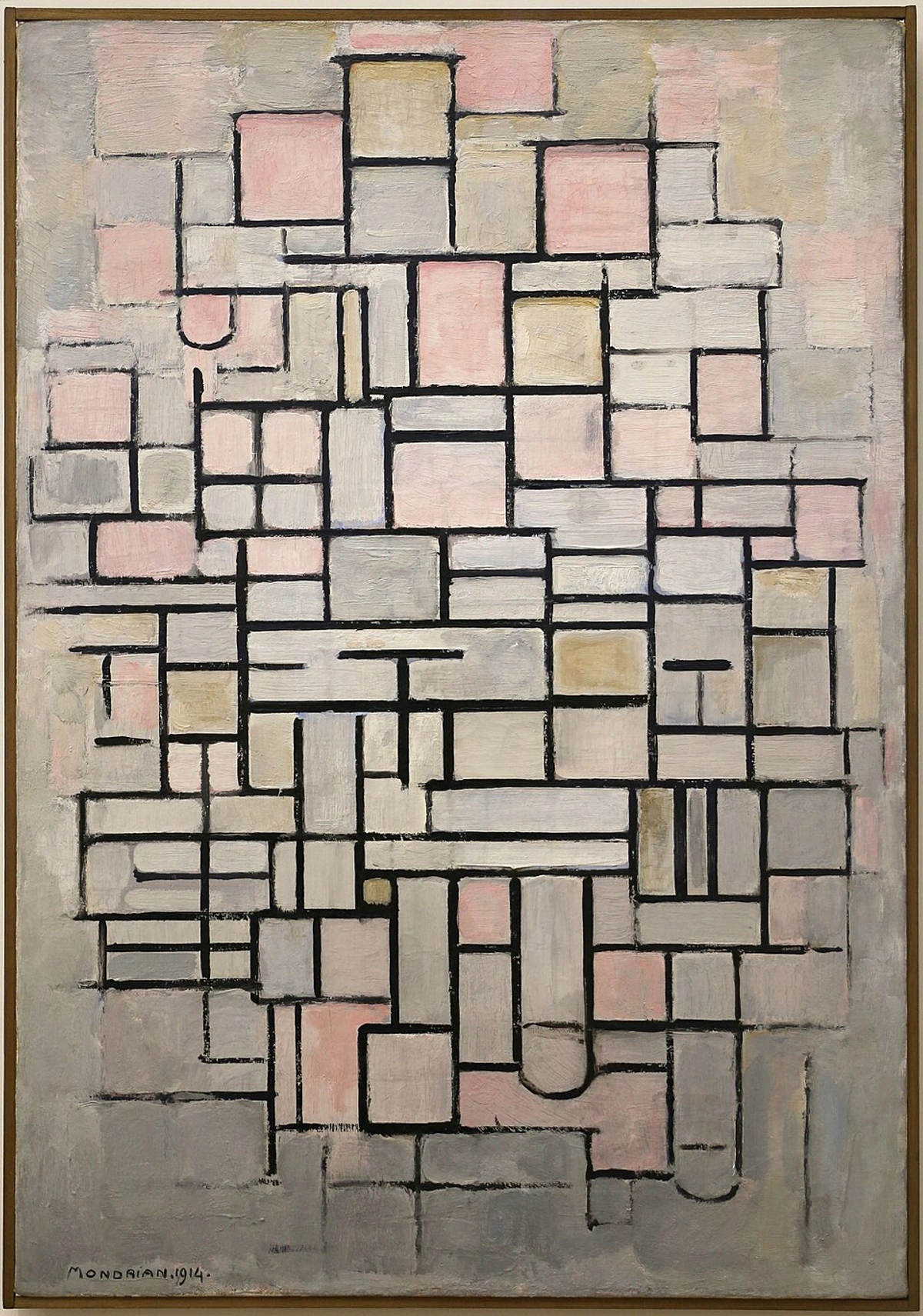

Or consider the pure geometric abstraction of someone like Mondriaan, completely detaching from the human form. When I first encountered such radical departures, I admit, I wondered if all those hours studying classical forms were wasted. But the beauty is, understanding contrapposto helps us appreciate why these modern shifts were so radical. When an artist deliberately avoids the naturalistic flow of contrapposto, they're often making a conscious statement about form, perception, or the very nature of art itself. It's a bit like knowing the rules of grammar so intimately that you can write truly groundbreaking poetry; the deliberate deviation becomes a statement in itself.

For me, transitioning from more traditional art studies to abstract expression was a conscious choice. I found myself drawn to exploring those underlying principles of balance, rhythm, and tension through color and line, rather than anatomical representation. It wasn't a rejection of the past, but a desire to distill its essence into a new visual language. While I don't depict human figures, the energy of a shifted weight in a classical figure finds an echo in the way a strong diagonal line meets a vibrant color block in my own abstract compositions, creating its own sense of movement and harmony. It’s a contemporary 'contrapposto' of visual tension and release, aiming for that same dynamic balance the ancient masters sought, just in a different visual language – a fascinating evolution, don't you think? If you're curious about my approach, you can always explore my artist's journey or see art for sale directly.

Frequently Asked Questions about Contrapposto

Is contrapposto only for standing figures?

While most famously associated with standing figures, the principle of contrapposto—a dynamic counterbalance of the body—can be seen in reclining figures or even figures caught in active motion, though it's most visually striking in a relaxed standing pose.

How did contrapposto evolve in classical periods?

Early classical contrapposto, exemplified by Polykleitos's Doryphoros, was often quite restrained and harmonious, focusing on idealized balance. As Greek art moved into the Hellenistic period, contrapposto became more dramatic, exaggerated, and emotionally charged – think of the intense twist of the Laocoön and His Sons – reflecting a broader shift towards heightened realism and intense emotional expression in sculpture.

Can contrapposto convey different emotional states?

Absolutely! A relaxed contrapposto might suggest serenity, confidence, or contemplation. A more strained or twisted contrapposto, especially when combined with facial expressions or gestures, can convey anxiety, defiance, pain, or even impending struggle, lending immense psychological depth to the figure.

Is contrapposto always obvious?

Not always! The beauty of contrapposto is often in its subtlety. In some works, it's very pronounced (like Michelangelo's David), while in others, it's a gentle hint of natural weight shift that makes the figure feel more alive without being overtly dramatic.

What's the opposite of contrapposto?

The direct opposite would be a rigid, symmetrical, and frontally oriented pose, often referred to as a "frontal" or "hieratic" pose, common in much ancient Egyptian or archaic Greek sculpture before the classical revolution.

Are there specific artists known for their mastery of contrapposto?

Absolutely! Beyond Polykleitos (who developed a Canon of Proportions inherently favoring contrapposto, exemplified in his Doryphoros, for its ideal mathematical balance) and Michelangelo (whose David is a monumental example, renowned for its psychological intensity and powerful, almost defiant, weight shift), other notable masters include Donatello (especially his bronze David and St. George, bringing a revolutionary naturalism to freestanding sculpture), Praxiteles (known for his more sensual and relaxed contrapposto, softening the classical ideal), and later Renaissance artists like Raphael and Leonardo da Vinci, who incorporated the principle into their paintings as well as sculptures, breathing life into their canvas figures.

My Final Thoughts: More Than Just a Pose

So, contrapposto. Not just a fancy word, but a profound artistic invention that completely changed how humans were depicted in art. It gave figures life, emotion, and an undeniable sense of humanity, allowing artists to tell richer, more engaging stories. For me, grappling with terms like this reminds me that even when my own art veers wildly into abstraction, it's built upon centuries of visual language and a shared human desire to express movement, balance, and feeling. Understanding the "rules" of the past makes me a more thoughtful "rule-breaker" today, allowing me to consciously inform the dynamic tensions I seek in my own abstract compositions. It’s all part of the grand, beautiful conversation that is art, and I’m just happy to contribute my voice and perspective to it. What a journey, right?