Multi-Panel Art Demystified: Diptychs, Triptychs, Polyptychs & Their Stories

Join a curator's journey through multi-panel art. Explore the history, psychological impact, and compositional secrets of diptychs, triptychs, and polyptychs, from ancient altarpieces to contemporary abstract works. Discover how artists use multiple canvases to unfold vast narratives and challenge perception.

Unfolding Narratives: A Curator's Personal Journey Through Diptychs, Triptychs, and Polyptychs

I've always been utterly fascinated by how a story, a feeling, or even just one grand idea can simply outgrow a single canvas. It’s like some narratives just demand more room to breathe, to truly unfurl and let their ideas echo and play off each other. This is precisely why multi-panel artworks – from the intimate diptych to the expansive polyptych – have always felt like a secret language I'm still learning to speak fluently. They're not just decorative divisions; they're profound invitations to explore narrative, symbolism, and expansive visual ideas, offering intricate storytelling and a unified yet segmented vision. As a curator, this journey through two, three, or even many panels has been a constant source of wonder, and I want to share that discovery with you, exploring their history, artistic applications, and enduring appeal. I think you'll find, as I have, that these formats excel at conveying complex emotions, showing transformations, or simply giving grand ideas the space they truly deserve.

So, What Exactly Are These Multi-Panel Wonders?

When I first started really seeing art, not just looking, these multi-panel works just stopped me in my tracks. It was like someone had taken a single thought and decided to give it room to breathe, to expand, to really become something more. At their core, multi-panel artworks are compositions of multiple panels intended to be viewed as a cohesive unit – and that's the crucial bit. It means they're meant to be seen as one complete, inseparable idea, not just separate pictures hanging near each other. The deliberate choice of two, three, or many panels isn't arbitrary; it’s a fundamental decision that shapes the entire experience. It dictates the rhythm, the narrative potential, and the viewer's journey through the work. It's this interplay between separation and cohesion that genuinely fascinates me. Our minds, instinctively, seek to bridge the gaps, to find continuity and meaning where there are physical divisions. This active mental reconstruction deepens our engagement, turning a passive viewing into an immersive psychological dance where the whole is greater – and often more profound – than the sum of its parts. It feels like solving a beautiful visual puzzle, but one that challenges your perception and invites a richer, more contemplative experience.

The Diptych: A Duality in Art

A diptych (from Greek di- "two" and ptyche "fold") consists of two panels. There's something so inherently human about a diptych, isn't there? It’s like looking at two sides of a coin, or maybe two sides of yourself that are always in subtle conversation. I often find myself playing with that tension in my own work – the light and the shadow, the loud and the quiet. Historically, these often functioned as hinged writing tablets in Roman times or as intimate devotional images in the Middle Ages. The two panels could either present a continuous scene, a before-and-after narrative, or two complementary subjects designed to be seen in conversation with each other. The physical hinge itself, when present, can even act as a symbolic element, representing both the connection and the potential for separation or revelation between the two worlds depicted. The Diptych of Consuls: Rufius Gennadius Probus Orestes (Constantinople, 534 AD) is a prime example of this historical function, where two panels combine to commemorate an individual with symbolic carvings. Think of it as a contrast between:

- The mundane and the sublime

- The internal and external self

- A memory and its present-day echo

- A husband and wife, or other significant individuals in a secular portrait.

This duality creates a powerful psychological tension, forcing the viewer to hold opposing ideas or emotions simultaneously, often inviting intimate reflection. For me, it's this delicate balance, this forced comparison, that truly amplifies the emotional resonance of the artwork. It’s a potent format for exploring relationships, transformations, or contrasting states of being.

The Triptych: A Story in Three Acts

From the intimate pairing of a diptych, we move to the more structured narrative of the triptych. Perhaps the most recognized form, a triptych (from Greek tri- "three") is an artwork composed of three panels. Often, the central panel is the largest and most prominent, flanked by two smaller wings. It’s like the headliner and its opening acts, all working together to create a show. These side panels might fold inward, protecting the central image, or remain fixed. The three-part structure naturally lends itself to a narrative arc, allowing for a beginning, middle, and end, or perhaps a central theme with supporting elements on either side. While often narratively driven, I've also seen triptychs used to explore a single theme from three distinct perspectives, or to dissect an emotion into its constituent parts – a kind of "thesis, antithesis, and synthesis" that isn't always linear, especially in contemporary or abstract works. Imagine one panel exploding with vibrant energy, another offering quiet contemplation, and the third finding a harmonious synthesis between the two. It’s like a little journey, a mini-narrative that unfolds right before your eyes. Sometimes, my own studio process feels exactly like that, an idea evolving in three distinct phases! Its association with altarpieces, symbolizing concepts like the Trinity or past/present/future, has cemented its place in art history as a powerful format for telling expansive stories in a focused sequence.

The Polyptych: An Expansive Vision

And then you get to the polyptychs... wow. When an artwork comprises more than three panels, it is generally referred to as a polyptych (from Greek poly- "many"). Basically, when the artist ran out of excuses to stop adding panels – just kidding, mostly! These grander compositions allow for extensive narratives, a multitude of characters, or the depiction of complex, multi-faceted themes. The sheer scale and ambition of a polyptych demand close examination, revealing layers of meaning with each glance. The Ghent Altarpiece by Jan van Eyck is perhaps the most famous example, with its intricate array of panels designed to open and close, revealing different scenes depending on the liturgical season or occasion. I remember seeing a polyptych once and just feeling completely overwhelmed, in the best possible way. It makes you think, 'What kind of grand vision could possibly demand that much space? And what kind of incredible planning and resources did it take to even conceive, let alone construct, such a monumental work?' Beyond the creation, just viewing a truly massive polyptych in a gallery can be a feat – you're often stepping back, then moving closer, almost performing a dance with the artwork itself. This interactive element transforms the work from a static image into a dynamic, unfolding narrative, often possessing an architectural quality, offering a truly grand pronouncement of artistic and theological vision.

A Journey Through History: The Evolution of Multi-Panel Art

Having explored their fundamental forms, let's now journey back through time. These forms aren't just clever compositional tricks; they have a deep, rich history that's as fascinating as the art itself. The use of multiple panels is not a modern invention; its roots stretch back through millennia, evolving significantly through various epochs and cultural contexts. Their development is deeply intertwined with human history and artistic expression, reflecting societal changes and artistic innovations.

From Ancient Tablets to Sacred Spaces

The earliest forms of multi-panel compositions can actually be traced back further than Roman times. Ancient Egyptian funerary objects sometimes featured multiple surfaces for sequential imagery, and early illuminated manuscripts often used paired or grouped pages to create continuous narratives. Imagine a medieval scribe, carefully illustrating a biblical passage across two facing pages, treating them as a single canvas. They’d extend a landscape, a grand architectural setting, or even a procession of figures, ensuring the eye flowed seamlessly from left to right, making the act of turning the page feel like progressing through a scene rather than simply starting a new one. This deliberate pairing created a powerful sense of narrative continuity, often amplifying the drama of the depicted events. By Roman times, hinged wax tablets (early multi-panel notepads, if you will) were common for writing. By the early Christian era, these evolved into ivory diptychs depicting religious scenes or portraits, used for commemoration. However, it was during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance that multi-panel artworks, particularly triptychs and polyptychs, reached their zenith, primarily as altarpieces for churches and cathedrals.

These sacred works served a crucial function, often illustrating biblical stories, lives of saints, or complex theological concepts and doctrines. Artists of this period often employed rich materials and intricate techniques, such as tempera on wood, oil painting, extensive gilding for divine light, and intricate carving, to create works of breathtaking beauty and spiritual depth. The folding panels added an interactive element. This wasn't just for show; it was a teaching tool, a way to reveal deeper spiritual truths or to tailor the message to specific feast days, making the artwork a living, breathing part of worship. The closed panels often presented a more subdued scene, perhaps a grisaille (a painting executed entirely in shades of grey or another neutral color), serving a symbolic function by representing the mundane world or a preparatory state, while the opened panels burst with color and dramatic content, reserved for special occasions. The complexity and artistry of these pieces not only served devotional purposes but also became powerful statements of faith and artistic skill, reflecting the era's deep spiritual devotion and the significant investment from patrons.

Beyond the Church: Secular Narratives and Portraits

While deeply rooted in religious contexts, multi-panel art eventually transcended the sacred. This shift was often influenced by changing patronage, with wealthy merchants, nobles, and even royalty commissioning artworks for private devotion, portraiture, or the commemoration of significant personal or historical events. These patrons sought to display their status, piety, or achievements, and multi-panel works offered a grand format for such statements. Renaissance artists began to explore secular themes, using diptychs for portraits, often depicting a husband and wife on separate panels, creating a dialogue of status and affection. Beyond simple portraits, these works could depict allegorical tales of virtue, historical battle scenes, or even grand statements of family legacy, often flanked by coats of arms. Jean Fouquet's Melun Diptych is a notable example, though still religious, it showcases the evolving artistry of portraiture within a multi-panel format. This broadening of purpose allowed for more intimate contemplation and personal connection, signifying a shift in artistic patronage and intention.

Artistic Intent and The Joys (and Headaches) of Composition

Now that we've walked through the ages, let's step into the artist's studio and get down to the nitty-gritty: what makes these multi-panel works work from an artist's perspective? Creating a compelling multi-panel artwork requires a profound understanding of composition in art and how individual elements coalesce into a unified whole. It is here that the artist's hand truly shapes the viewer's experience, often navigating intriguing visual challenges inherent in segmenting a larger vision.

When I'm wrestling with a multi-panel piece, the biggest question is always: how do I make these separate bits sing together? It’s not just about making them look pretty side-by-side; it’s about creating a conversation, a dance. Sometimes it feels like herding cats – especially when you're trying to get a specific emotional cadence across three distinct panels – but when it works... oh, it works.

The Practicalities: Crafting a Multi-Panel Work

Beyond the aesthetic and conceptual challenges, artists grapple with very real, practical hurdles when creating multi-panel art. Imagine ensuring consistent material quality across multiple canvases or wooden boards, especially for larger polyptychs where slight variations could disrupt the overall harmony. I once had a client commission a large diptych, and after weeks of work, discovered that one of the wood panels was subtly warping, throwing off the entire intended alignment! It was a headache, to say the least. Then there's the monumental task of physically joining, framing, and ultimately, transporting these often massive creations. Each panel needs to align perfectly, the surface textures must be uniform (unless intentional contrast is desired), and the structural integrity has to withstand the test of time and movement. You also have to consider how the materials will age over time – will one panel's paint crack differently than another's? It's a testament to an artist's dedication that they navigate these logistical complexities to bring their grand visions to life.

And speaking of headaches, let's talk about scale. When you're dealing with multiple panels, you're not just composing on individual surfaces; you're composing for an entire wall, sometimes an entire room. The sheer physical presence of a large polyptych can be overwhelming, demanding a different kind of vision from the artist and a different kind of engagement from the viewer. I remember once working on a series that started as individual pieces, but as I arranged them, the space between them started to feel like its own powerful element, influencing the entire rhythm of the final work. It wasn't just paint on canvas anymore; it was an environmental statement.

It's this complex dance between individual panels and their collective impact that defines the mastery of multi-panel art. So, how do artists navigate this intricate terrain?

Unity and Continuity

One of the primary challenges and triumphs of multi-panel art lies in establishing unity across disparate canvases. It’s like trying to get a group of very opinionated friends to agree on a movie – everyone has their own thing, but you need them all to harmonize for the evening to work. Artists achieve this through various means, creating not just visual harmony but also a psychological sense of completeness, a visual rhythm that guides the eye:

- Continuous Landscape or Background: A seamless vista stretching across all panels, often seen in large altarpieces, visually stitching the work together. Think of a sweeping sky that unifies separate scenes across a triptych, creating a serene cadence.

- Recurring Elements of Art: Consistent use of color theory, line, or form that guides the viewer's eye and creates cohesion. For example, a dominant color palette used across all panels can bind disparate images into a single emotional experience. This also includes creating visual rhymes or echoes – repeating shapes, gestures, or patterns subtly across panels to reinforce connection. Sometimes, even the negative space or the physical gaps between panels are intentionally used as compositional elements, guiding the eye or emphasizing the fragmentation as part of the overall unity. I've seen contemporary abstract artists use a carefully placed sliver of unpainted canvas between panels to create a striking new line, a visual breath that's just as deliberate as a painted stroke.

- Shared Light Source or Perspective: A consistent source of light and perspective ensures visual harmony and a believable space, making the separate panels feel like windows into the same reality.

Contrast and Juxtaposition

Conversely, multi-panel works also excel at exploiting contrast. As an artist, I find this particularly compelling – it’s a way to really make two ideas ping off each other. Artists might place opposing ideas, emotional states, or chronological moments side-by-side, enhancing their impact. This isn't just for visual interest; it's to amplify the meaning of each element by placing it in direct dialogue with its opposite, forcing the viewer to consider the nuances of each. For example, one panel might depict a scene of vibrant celebration while an adjacent panel portrays quiet contemplation, creating a powerful dialogue between states of being. The separation of panels naturally lends itself to creating distinct yet related scenes, allowing for powerful juxtapositions that would be difficult to achieve on a single canvas. Roy Lichtenstein's iconic Whaam!, for instance, uses two canvases to dramatically contrast the explosive action of a fighter jet with the ensuing destruction, making the narrative impact undeniable across the two separate, yet interconnected, panels. In contemporary abstract art, this contrast might be more subtle but equally potent. Imagine a diptych where one panel features a swirling vortex of cool blues and greens, evoking a sense of calm, while its counterpart bursts with jagged, aggressive reds and oranges, suggesting turmoil. Or perhaps contrasting textures – a smooth, glossy panel next to one with heavy impasto. The stark emotional and chromatic juxtaposition forces a dialogue that wouldn't be as impactful on a single canvas, inviting us to reconcile these opposing forces within a unified aesthetic experience.

Narrative Flow and Time

The sequential nature of panels offers a unique way to depict time and narrative. A diptych might show "before" and "after" – consider a diptych illustrating a landscape before and after a storm, a subject in youth and old age, or a profound psychological shift. A triptych can illustrate the progression of a story, such as the life of a saint or a biblical sequence. Polyptychs, with their expansive surfaces, can unfold epic sagas, guiding the viewer through multiple scenes and subplots, much like chapters in a book. This temporal dimension adds a layer of intellectual engagement for the observer, encouraging a slower, more deliberate viewing process.

Interactive Elements: The Unfolding Story

Many historical multi-panel works were designed to be opened and closed, revealing different configurations. This interactive aspect transformed them from static images into dynamic objects, where the act of viewing became a performance. The closed panels often presented a more subdued scene, perhaps a grisaille, serving a symbolic function by representing the mundane world or a preparatory state, while the opened panels burst with color and dramatic content, reserved for special occasions. This element of revelation heightens the impact and sacrality of the artwork. This wasn't just for show; it was a pedagogical tool, a way to reveal deeper spiritual truths or to tailor the message to specific feast days, making the artwork a living, breathing part of worship.

Multi-Panel Art in the Modern Era: A Vibrant New Accent

While the historical foundations are crucial, the true magic for me lies in how these forms continue to breathe and evolve in contemporary studios. The spirit of multi-panel art has found new life, as contemporary artists have embraced and reinterpreted these structures, pushing their boundaries beyond religious or historical narratives to explore new artistic frontiers, demonstrating the enduring versatility of the format.

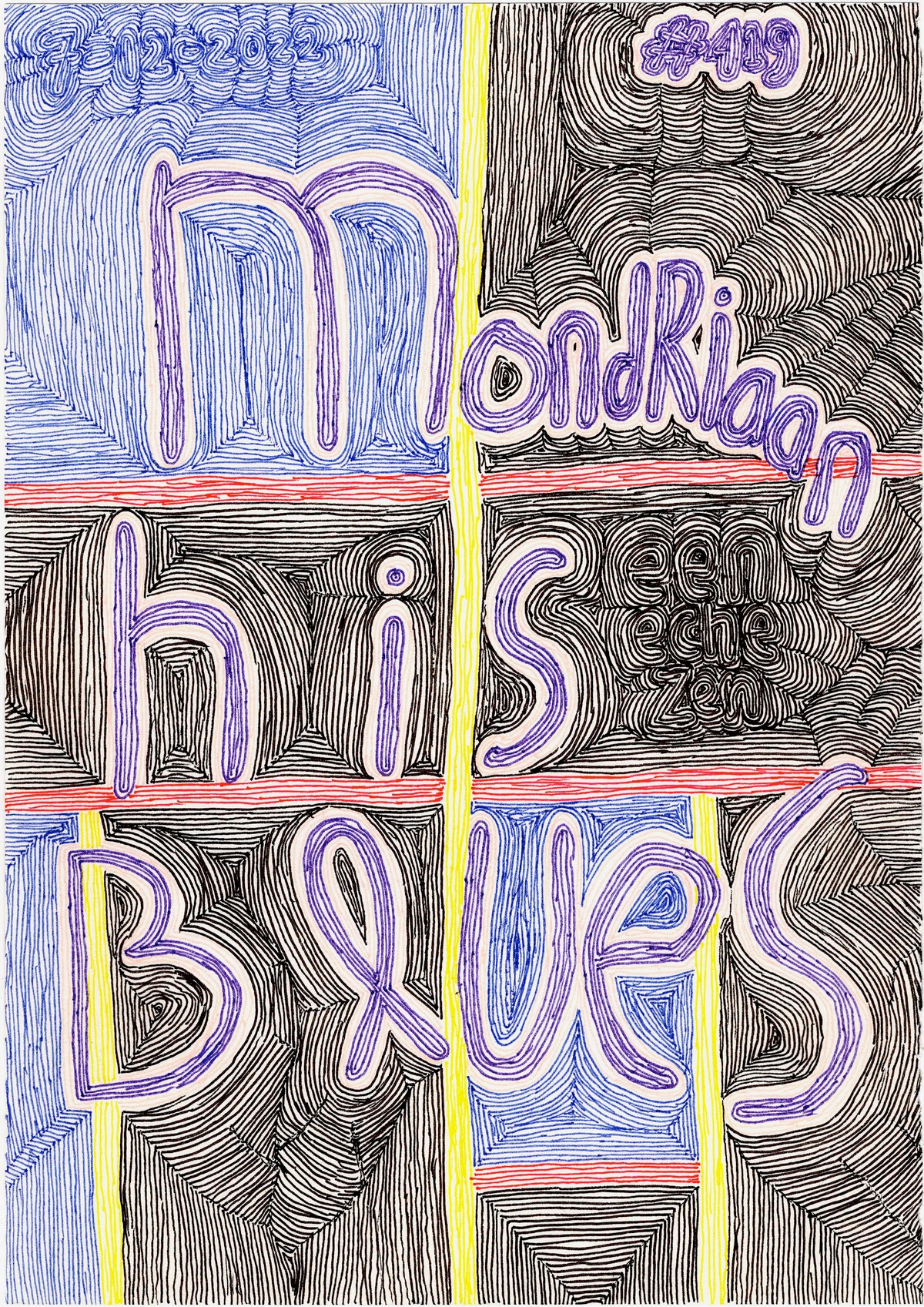

Abstract and Contemporary Interpretations

This is where things get really exciting for me. Seeing how artists today use these structures not for straightforward stories, but for pure feeling, for exploring color and form in ways that feel utterly new. It’s like taking that ancient language and giving it a modern, vibrant accent. I find myself constantly inspired by how a simple division can completely change the energy of a piece. In the 20th and 21st centuries, artists have adopted diptychs, triptychs, and polyptychs to explore abstract concepts, emotional landscapes, and purely formal concerns. Here, the panels might not depict a sequential narrative but rather variations on a theme, fragmented views, or a deconstructed whole. It’s like they’re saying, 'Let’s take this idea, chop it up, rearrange it, and see what happens!' And usually, something brilliant happens. Abstract artists often use multiple panels to explore texture, space, or geometric relationships. For example, a diptych might present two subtly different color palettes—one panel featuring bold, primary colors while the other explores muted earth tones—creating a dynamic dialogue between intensity and subtlety, or exploring the subtle shift in a color's temperature. A triptych could present a single form from three radically different viewpoints, challenging our perception of its solidity, perhaps with one panel showing a close-up texture, another a wider context, and a third a completely deconstructed view. The fragmentation can manifest as a single image split across panels, or distinct abstract compositions that share a visual language but offer varied perspectives, inviting the viewer to mentally reconstruct a larger, implied whole. Beyond purely formal concerns, contemporary multi-panel works often delve into themes of memory and identity, reflecting on how our experiences are fragmented and reassembled over time. Artists might use multiple panels to explore the shifting nature of self, or to comment on the pervasive influence of the digital age where information is constantly fractured, presented in discrete windows, and yet expected to form a cohesive whole in our minds – much like scrolling through a social media feed or flipping between browser tabs. It's a powerful way to mirror the complexity of modern perception.

For instance, an artist might use a triptych to explore the evolution of a brushstroke or the layering of different materials, creating a tactile story across the surfaces. This focus on process and material, rather than just subject, is a hallmark of contemporary multi-panel abstraction. Similarly, a polyptych might become an expansive field of vibrant geometric abstraction, drawing the eye across a vast canvas of interconnected forms, with each panel offering a slightly different angle or emphasis within the overall composition.

Andy Warhol's iconic Marilyn Diptych exemplifies this reinterpretation, using repetition and striking color variation across two panels to explore themes of celebrity, mortality, and mass media culture. The repeated imagery and fading hues on one side powerfully comment on the transient nature of fame and the dehumanizing aspects of mass production.

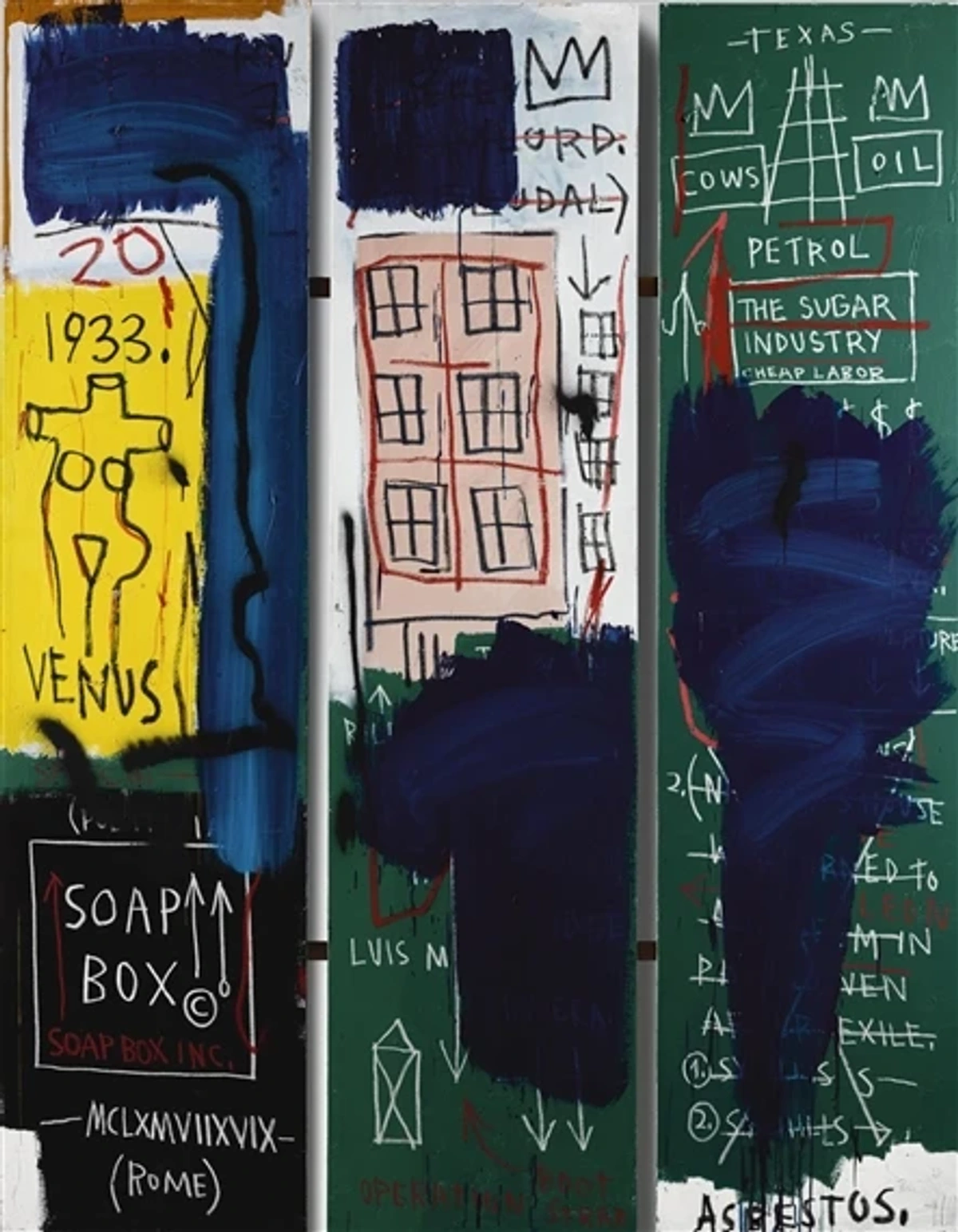

Beyond the Canvas: Photography, Sculpture, and Mixed Media

The concept of multi-panel artwork has also expanded beyond traditional painting. Photographers create diptychs and triptychs to present a series of related images, exploring narrative or theme through sequence—think of a photographic diptych capturing a changing expression over time, different perspectives of a single subject, or showing a subject's transformation over minutes or years. Sculptors, too, have embraced this multi-panel philosophy, creating modular sculptures or multi-part installations that function as three-dimensional polyptychs. Here, distinct sculptural elements are arranged to be viewed in sequence or from multiple angles, exploring spatial relationships and varied viewpoints – imagine walking around several distinct, but related, geometric forms, and as your perspective shifts, a new, continuous story unfolds. Similarly, mixed media artists often combine various materials across panels to add tactile and visual complexity, leveraging the panel divisions as compositional elements themselves, allowing different textures to engage in a unique dialogue. Contemporary artists like Jean-Michel Basquiat frequently employed multi-panel formats, using them to create complex, layered narratives filled with symbols, text, and raw energy. His works often juxtapose diverse elements across panels, building a rich, fragmented dialogue that reflects the complexity of modern experience.

Appreciating Multi-Panel Works: A Guided Viewing

So, you've seen them, you've understood them, now how do you truly experience them? Approaching a multi-panel artwork offers a unique viewing experience, inviting observers to engage with it not merely as a collection of individual pieces but as an integrated whole, a conversation between segments. As a curator, I encourage viewers to embrace this dynamic interplay, allowing the artwork to unfold its secrets at its own pace.

Practical Guidance for the Viewer

When I'm looking at a multi-panel piece, I try to do a few things. First, I just let it wash over me... the whole thing. I try to get a sense of its overall presence, its scale, its initial emotional impact. Then, I start to zoom in, panel by panel, like I’m dissecting a really interesting thought, before stepping back to see how the individual pieces contribute to the larger puzzle.

- Observe the Overall Impact and Scale: Begin by observing the entire composition to grasp the overall impact, unity, and physical scale. For a large polyptych, the sheer expanse contributes significantly to its immersive quality. Does the sheer size of a polyptych make you feel small and awestruck, or does it draw you in like a portal? Then, move closer to examine each panel individually, appreciating its unique details and how it contributes to the larger narrative or aesthetic.

- Analyze Relationships and Dialogue: Actively seek the connections between the panels. Are they sequential, contrasting, complementary, or variations on a theme? Look for visual rhymes or echoes between the panels – a repeated color, a gesture, a line that continues across a divide. Also, pay attention to the edges where panels meet; sometimes a new shape or tension is created right there in the gap. Understanding these relationships unlocks deeper meaning and enriches the viewing experience, revealing the artist's conceptual intentions.

- Follow the Narrative (or Abstraction): If the work is narrative, endeavor to follow the story or concept from panel to panel. How does the artist use the divisions to enhance the storytelling and pace the unfolding events? If it’s abstract, the 'narrative' might manifest as an emotional arc or the development of visual ideas. Observe how forms, colors, or textures develop, contrast, or echo across the panels, and how they might imply a larger, unseen structure or concept, or even a subtle shift in mood. What journey do your eyes take? What emotional resonance does the artist create by segmenting these visual ideas?

- Consider the Artist's Formal Choices: Reflect on the artist's deliberate decision to employ a diptych, triptych, or polyptych format. What advantages does this structure offer for their particular message or aesthetic, and how might the work differ if presented on a single canvas? What couldn't they achieve on one surface? This structural choice is a fundamental aspect of the artwork's meaning.

- Embrace the Physicality: Notice the physical attributes of the artwork—the joins between panels, the texture of the surfaces, the craftsmanship involved in their creation, and the way light interacts with the multiple planes. These physical elements contribute to the overall tactile and visual experience, often emphasizing the segmented nature of the whole.

- Evaluate Framing and Installation: The way a multi-panel work is framed or installed can significantly influence its perception. Are the panels tightly abutted, or is there space between them? How does this choice affect the sense of unity or fragmentation, and how does it interact with the exhibition space? How does the framing emphasize unity or highlight fragmentation?

Frequently Asked Questions about Multi-Panel Art

Q1: Is a multi-panel artwork always hinged?

A1: Not necessarily. While many historical diptychs and triptychs were hinged to allow for folding, contemporary multi-panel artworks are often displayed as separate, fixed panels intended to be viewed together. The key defining feature is their artistic cohesion as a single conceptual piece, regardless of physical connection. The artist's intent for the panels to be seen as a unified whole is paramount.

Q2: What's the difference between a multi-panel artwork and a series of paintings?

A2: A true multi-panel artwork (diptych, triptych, polyptych) is conceived as a single, unified work, where each panel is interdependent and contributes directly to a larger singular artistic statement or narrative. The removal of one panel would diminish the entirety of the intended message. While a series of paintings might share a theme or style and even be intended for sequential viewing, each piece in a series typically retains its primary meaning as a standalone work. The crucial difference lies in the inherent interdependence and singular artistic statement of a multi-panel work, making it a truly indivisible entity.

Q3: Can abstract art be presented as a diptych or triptych?

A3: Absolutely. Modern and abstract artists frequently utilize multi-panel formats. This allows them to explore variations in color, form, or composition across separate panels, creating a dynamic dialogue within the overall artwork without relying on a traditional narrative. It serves as a powerful way to engage with fragmented views of a larger whole, to present a theme through serial visual investigations, or to explore the fragmentation of perception and the simultaneous existence of multiple realities, making it a compelling choice for abstract art.

Q4: Does the physical arrangement of the panels matter in multi-panel art?

A4: Absolutely! The artist's choice in arranging the panels—whether tightly abutted, with deliberate gaps, in a horizontal row, a vertical stack, or even staggered—significantly impacts the viewer's experience and the work's meaning. These arrangements dictate rhythm, emphasize connections or discontinuities, and can create a sense of movement, tension, or harmony that is integral to the overall composition.

Q5: Are there any famous polyptychs besides the Ghent Altarpiece?

A5: Yes, several notable examples exist, each magnificent in its own right. Rogier van der Weyden's The Last Judgment (Beaune Altarpiece) is renowned for its intricate details, emotional intensity, and profound theological narrative, with its central panel depicting Christ in judgment, flanked by vivid scenes of heaven and hell. Another monumental work is Duccio di Buoninsegna's Maestà (Siena Cathedral altarpiece), which revolutionized Sienese painting with its narrative complexity, emotional expressiveness, and innovative use of multiple panels to illustrate the life of the Virgin Mary and Christ, showcasing groundbreaking techniques for its era. Both are pivotal in their respective art historical periods for their profound impact and storytelling capabilities, showcasing incredible detail and complex iconography.

Q6: What considerations should I have when collecting multi-panel art?

A6: Collecting multi-panel art offers a unique opportunity to acquire works with significant presence. Practical considerations include the substantial space required for display, as these pieces often demand an entire wall to be fully appreciated – think about how it would transform a home versus a vast gallery space. Their complexity and scale also inherently influence pricing; they represent a greater investment of time, materials (multiple supports, frames, and pigments), and sheer artistic labor, often resulting in higher price points reflective of the monumental effort and vision involved. When considering a purchase, reflect on how such a piece interacts with its intended space, recognizing its ability to transform an environment through its dynamic presence. Contemporary abstract art by artists exploring these themes, for instance, offers unique perspectives on unity and fragmentation, providing opportunities for profound aesthetic statements. If you're interested in supporting artists and finding a piece that speaks to you, perhaps consider exploring art for sale directly, or even visiting an artist's studio or gallery for a deeper understanding.

Conclusion

Ultimately, for me, creating and appreciating multi-panel works is about more than just dividing space; it’s about exploring complexity, finding harmony in multiplicity, and experiencing the sheer joy of an idea blooming across multiple surfaces. Each division isn't a limitation but an opportunity to deepen the narrative, amplify contrast, or simply invite a richer, more contemplative pause. The next time you encounter a diptych, triptych, or polyptych, I hope you'll see not just separate pieces, but a whole world waiting to be discovered – a testament to the artist’s profound vision and relentless pursuit of expression. Perhaps you'll even find yourself inspired to explore how these principles resonate with your own creative journey, just as I've integrated these multi-panel concepts into my own studio practice. You can discover more about my personal artist's journey or visit my museum in 's-Hertogenbosch, where you'll often encounter my vibrant, abstract multi-panel works, each panel telling a part of a larger, unfolding story. And if you’re looking to add a piece that encourages this unique visual dialogue to your own collection, remember to explore the art for sale directly from the studio.