Collage Art's Layered Journey: From Cubist Rebellion to Digital Frontiers & Ethical Debates

Explore the revolutionary history of collage art through a personal lens. Trace its evolution from Cubist fragmentation and Dada's rebellious photomontages, through Surrealist dreamscapes and Pop Art's consumer critique, to contemporary mixed media, digital innovation, and crucial ethical discussions on appropriation. A comprehensive guide for artists and enthusiasts alike.

You know, there’s this quiet, almost conspiratorial thrill I get from taking things that don’t quite belong together – a torn map, a stray thought, a snippet of a song – and watching them fuse into something entirely new. Maybe it’s the way my own life often feels like a beautiful, glorious mess of disparate experiences, but I’ve always been drawn to the imperfect, the pieced-together, the miraculous moment when fragments find their whole. Just last week, wrestling with a painting, feeling utterly blocked, I stumbled upon an old, discarded map in my studio. Gluing that humble fragment onto the canvas immediately shifted the entire composition, creating an unexpected depth and a narrative of journey I hadn't foreseen. That, my friends, is the raw, beating heart of collage art for me. It's more than an art form; it’s a philosophy, a way of seeing the world in pieces and daring to reassemble them. There’s a profound, almost cathartic joy in finding beauty in the discarded, in the unexpected juxtaposition. Today, when we casually toss around terms like mixed media, it feels so natural, so ubiquitous, influencing everything from graphic design to film editing. But the path to this point was anything but smooth – a wild, rebellious ride that pushed boundaries from physical fragments to digital layers, and yes, even sparked crucial conversations about ethics and authorship, particularly the fine line between creative appropriation and outright infringement. These are concerns that continue to shape contemporary artistic practice, making collage as relevant as ever. So, settle in, grab your favorite brew, and let’s trace this revolutionary journey chronologically, from its explosive Cubist beginnings, through the defiant spirit of Dada and the dreamscapes of Surrealism, to its vibrant present in contemporary mixed media, and even a peek into its fascinating digital future. We’ll explore how these seemingly simple acts of assemblage transformed art and continue to inspire creators across disciplines, forming a comprehensive roadmap of artistic evolution and the questions it poses.

Zenmuseum, https://zenmuseum.com/

The Big Bang: When Cubism Ripped Up the Rules (and Newspapers)

Think about it: painting was, for centuries, about creating an illusion on a flat surface. Then came Cubism, and suddenly, that illusion was shattered. Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, bless their brilliant, rule-breaking hearts, didn’t just paint objects from multiple perspectives; they started incorporating pieces of the real world directly onto their canvases. This wasn't just groundbreaking; it was a bold challenge to centuries of artistic tradition that prized the seamless illusion and the painter's singular, skilled hand. They were reacting to a world rapidly changing with photography and mass media, where images were increasingly fragmented and readily consumed – why shouldn't art reflect that new reality? The Cubists were essentially saying, “Hey, the world isn't neat and tidy; why should our art be?” And honestly, that resonates with my own approach to abstract art – sometimes, embracing the chaos is the most honest thing you can do (and often, the most fun, let’s be real).

For me, it was that jarring sensation – that unexpected meeting of high art and mundane reality. The rough edge of the newsprint against the painted canvas, the actual words staring back at you… it truly defined their radical approach, forcing you to question what was real, what was painted, and what was simply there. Imagine the audacity! Taking a piece of newspaper, a scrap of wallpaper, or a fragment of patterned paper – mundane, everyday objects – and gluing them into a painting. This wasn't about rendering a newspaper; it was the newspaper itself. This distinction was crucial, as it fundamentally challenged the illusionistic premise of painting, bringing material reality directly into the artwork's space, asserting its presence beyond mere representation.

They called it papier collé (glued paper) or collage, and it completely blew open the doors of what art could be. Using materials like newsprint, actual wallpaper patterns, or even scraps of fabric alongside oil paint and charcoal, Cubist collages offered a tactile, multi-layered experience. This blend of painted and 'found' elements didn't just add texture; it forced a new visual engagement, making the viewer acutely aware of the artwork's physical construction. This approach didn't just challenge the notion that an artist's skill lay solely in mimicking reality with paint; it also reflected a world rapidly changing with the advent of photography and mass media, where images were increasingly fragmented and readily consumed. Early cinema, for instance, presented a rapid succession of images, while newspapers offered fragmented glimpses of global events, echoing the fractured experience of modern life. The purpose of these works was aesthetic exploration: to challenge fixed perspective, break traditional representation, and reveal multiple facets of reality in a single frame. And if you're curious about influences, this fragmented vision was deeply influenced by non-Western art, particularly the abstract and stylized representations found in African masks and Iberian sculpture. These showed Picasso and Braque how forms could be deconstructed and multiple viewpoints presented simultaneously – for instance, by showing a face from both frontal and profile views, or breaking down a figure into geometric planes – a task that collage readily facilitated by allowing them to literally break apart and reassemble forms.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/gandalfsgallery/20970868858, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.0/

For more on this revolutionary movement, you might find my guide to Cubism insightful. Through collage, Cubism initiated a profound dialogue between art and reality, fundamentally altering the course of modern art. It asked us to see the world not as a singular, perfect image, but as a collection of moments and perspectives. Can you imagine the shock? What happens when art stops merely imitating life and starts actively incorporating it? The tactile nature of these works, the deliberate friction between the painted and the 'real,' was a radical departure, forcing a new kind of engagement with the artwork itself.

Dada's Provocation: Collage as Rebellion and the Birth of Assemblage

Just as the dust was settling from Cubism's explosion – having shattered traditional perspective and introduced literal fragments of reality – along came Dada. Born from the chaos and despair of World War I, Dada artists weren't interested in beauty or logic; they wanted to shake things up, challenge authority, and scream into the void. Figures like Tristan Tzara and Hugo Ball, through their provocative manifestos and anarchic performances at venues like the Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich, laid the groundwork for a movement that scorned convention. And guess what? Collage was their perfect weapon, a direct assault on the very idea of artistic sanctity. The fragmentation and absurdity of their collages mirrored the fractured reality and perceived irrationality of a world consumed by war, making a visceral statement against the senselessness they witnessed. It was a raw, defiant cry against the very systems that had led to such destruction, systems that often relied on carefully constructed narratives and propaganda. Dadaists used the very tools of mass media against itself, disassembling and reassembling its persuasive imagery to expose its manipulative power. I’ve certainly had moments in my own life where the only logical response felt like embracing pure, glorious chaos. This anti-establishment stance, using art as a form of social and political commentary, set a precedent for future movements, including the strategic use of imagery for counter-propaganda during and after wartime. So, what does it mean to use art as a weapon against the systems that create such destruction?

While Cubists used collage to explore new visual language, Dadaists wielded it like a blunt instrument – a joyful act of cultural sabotage – precisely because it incorporated mundane, ready-made materials from newspapers and advertisements. They grabbed images from magazines, newspapers, advertisements – the very fabric of society – and reassembled them into nonsensical, satirical, and often deeply political statements. Think of Hannah Höch's powerful photomontages, where she dissected gender roles and societal norms with a razor blade and glue stick. Her method involved precise cutting and layering of photographic fragments, often manipulating scale and playing with negative space to create biting commentary and grotesque juxtapositions, as seen in her iconic "Cut with the Kitchen Knife Through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany." This title, in its bluntness, critiqued the perceived decadence, political instability, and societal hypocrisy of post-WWI German society, particularly its male-dominated institutions. She used the very imagery of bourgeois life to critique it, turning the tools of mass media against itself. Or Kurt Schwitters, who, faced with the impossibility of rational art, collected scraps of rubbish from the streets to create his intricate Merz pictures – unique, abstract collages that transformed discarded materials into personal, immersive universes, reflecting the absurdity and fragmentation of post-war life. Schwitters even started creating entire walk-in environments, his Merzbau, as a kind of immersive, three-dimensional collage – essentially, an early form of assemblage, a broader category for artworks made from found objects, extending collage into three dimensions. Raoul Hausmann, another prominent Dadaist, also used photomontage to critique societal structures and the political climate, often blending photographic portraits with mechanical elements, as seen in his iconic "Mechanical Head (The Spirit of Our Time)" where he attached various measuring devices to a mannequin's head. Even figures like Marcel Duchamp, while known for his 'readymades,' certainly echoed the Dadaist spirit of challenging artistic convention and using everyday objects to provoke thought, aligning with the collage ethos. The purpose of Dadaist collage was undeniably political and social commentary, a raw, visceral protest against the irrationality of war and bourgeois values, making the mundane a weapon.

Zenmuseum, https://zenmuseum.com/

This wasn't just art; it was an act of cultural sabotage, a joyful destruction of traditional values. It highlighted the absurdity of modern life and the fragmented nature of perception. The enduring legacy of this rebellious spirit is something I often reflect on; if you’re curious, you can read more about Dadaism's influence. Dadaists proved that art could be a powerful, disruptive force, using collage to mirror and critique a fractured world. From Dada's raw rebellion and societal chaos, the art world, perhaps seeking a different kind of order, turned inward, plumbing the hidden landscapes of the mind. That's how the fragmented reality of collage became a portal to the subconscious, unlocking secrets we never knew existed.

Surrealism's Dreamscapes: Unconscious Assemblages

The path from societal upheaval to psychological exploration was a natural one. Then came the Surrealists, who, influenced by Freud's groundbreaking theories on the unconscious mind – his ideas about dreams as a 'royal road to the unconscious' and the power of repressed desires – took the fragmented reality of collage and plunged it into the subconscious. Freud's assertion that dreams offer a symbolic language of our deepest urges and fears provided a potent framework for artists seeking to bypass rational thought and express the irrational, especially in the wake of a devastating world war that challenged all previous notions of reason and order. This appeal to the irrational resonated deeply with artists disillusioned by the rationalist ideologies that had, in their view, led to such global destruction. Artists like Max Ernst used collage to explore dreams, irrationality, and the uncanny. Ernst, in particular, developed techniques like frottage (rubbing an object under paper to create a texture) and grattage (scraping paint from a canvas to reveal layers beneath), both of which, in their focus on revealing hidden forms and textures, echoed the spirit of collage by uncovering unexpected visual elements for incorporation. He frequently created compelling collages by juxtaposing Victorian engravings to create bizarre, fantastical scenes that felt both familiar and deeply unsettling – almost like waking up from a vivid dream you can't quite piece together. This sense of the "uncanny" often arises from the disruption of familiar contexts, forcing us to confront the irrational or the repressed desires surfacing from the subconscious. Beyond Ernst, figures like Dora Maar, known for her powerful photographic collages blending portraits with surreal elements, Eileen Agar (whose assemblages often incorporated found natural objects), Remedios Varo, Leonora Carrington, and even Man Ray (with his haunting photograms and collages) also wove dream-like narratives with cut and pasted fragments, each bringing their unique psychological lens to the uncanny. For them, the purpose was psychological expression: to tap into the hidden depths of the human mind and reveal the unconscious desires and fears that shape our reality, often evoking a profound emotional response in the viewer. The act of cutting and reassembling disparate images became a method for visual free association, bypassing rational thought to create a direct conduit to the subconscious. Techniques like automatic drawing (where the artist tries to draw without conscious control to express the subconscious) and exquisite corpse (a collaborative game where participants add to a drawing or text in sequence without seeing previous contributions, resulting in a surprising, often surreal composite) were direct analogues to the collage method, emphasizing chance and subconscious flow. These methods, by embracing the accidental and the illogical, were a deliberate attempt to subvert rational thought and allow the hidden currents of the mind to manifest visually.

Collage for the Surrealists was a way to bypass rational thought, to let the unconscious hand guide the scissors and the glue. The resulting images were often unsettling, beautiful, and profoundly psychological – like a waking dream made tangible, or a memory unexpectedly triggered by a bizarre combination of images. I remember a period when my own work felt heavily influenced by half-remembered dreams, where colors and shapes would emerge from a haze, guiding my hand in ways I couldn't explain. This idea of trusting intuition and letting materials lead the way is something I deeply connect with in my own exploration of mixed media. For more on this captivating movement, explore the enduring legacy of Surrealism. Surrealism transformed collage into a tool for introspective journeys, revealing the hidden landscapes of the human psyche. Moving from Surrealism's introspective dreamscapes, the art world shifted its gaze outward, from probing the subconscious to satirizing society's obsession with consumerism, using the very images it critiqued.

Pop Goes the Art: Mass Culture Meets the Scissors and the Combine

Fast forward to the mid-20th century, and collage found a new voice with Pop Art. Artists like Richard Hamilton and Peter Blake (who designed The Beatles' Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band album cover – a quintessential collage!) embraced consumer culture, advertising imagery, and popular media. The proliferation of readily available printing technologies and mass-produced magazines and newspapers made a vast archive of popular imagery accessible, fueling this artistic shift and inherently democratizing art materials. They cut out glossy magazine ads, comic strip panels, and celebrity photos, recontextualizing them to comment on the burgeoning consumerism and celebrity obsession of the era.

A precursor, or at least a powerful contemporary, Eduardo Paolozzi in the UK was already experimenting with collages made from American magazine clippings in the 1940s and '50s, a movement often associated with the Independent Group, which deeply influenced the nascent Pop Art movement by highlighting the burgeoning visual language of mass media long before Pop Art solidified its iconic status. Pop Art didn't just use these commercial images; it reflected on the persuasive power of commercial imagery itself, hinting at its potential for propaganda and shaping public desire, fundamentally altering how viewers perceived reality, art, and the commercial landscape around them. This deliberate engagement with popular culture created a shared visual language, making art more accessible while simultaneously critiquing the very systems that produced these images. Even someone like Andy Warhol, with his silkscreen prints, was conceptually playing with collage – taking existing images, repeating them, recontextualizing them, much like a cut-and-paste artist, forcing us to look at the mundane with fresh, often critical, eyes. I remember myself as a kid, poring over glossy magazine ads, never quite realizing they were silently selling me a dream, until Pop Art came along and started tearing them apart. American artists like Robert Rauschenberg, with his groundbreaking combines – essentially three-dimensional collages or assemblages (a broader category of art involving found objects, extending collage into three dimensions, which we briefly touched on with Schwitters' Merzbau) – literally blurred the line between painting and sculpture by incorporating found objects and images directly onto his canvases. His iconic work, Monogram (1955-59), famously features a taxidermied goat with a tire around its torso, standing on a painted panel – a stunning example of combining disparate elements into a new, often provocative whole, where assemblage incorporates collage. Jasper Johns also often integrated collaged elements and text into his work, using everyday signs and symbols in a fragmented, reassembled way, while Roy Lichtenstein, known for his comic book-style paintings, also conceptually embraced the cut-and-paste ethos by isolating and enlarging comic panels, recontextualizing them into 'high art' through his distinctive style. Pop Art's pioneering use of mass media imagery and recontextualization paved a crucial path for the digital manipulation of images we see in contemporary art today. The purpose of Pop Art collage was primarily social commentary, reflecting on and critiquing the images that saturated daily life, and even served to highlight the persuasive power of commercial imagery, hinting at its potential for propaganda.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/catmurray/13401878023, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.0/

Pop Art collage was often bold, graphic, and ironic. It blurred the lines between high art and popular culture, forcing viewers to reconsider the images that saturated their daily lives. It was accessible, playful, and yet deeply critical, showing us how we were being sold a dream, one glossy image at a time. It’s funny how those glossy magazine ads, once symbols of aspiration, now feel like historical artifacts themselves, pieced together to tell a new story. What lasting impact do you think this embrace of mass media imagery has had on how we consume and create art today? For a deeper dive into this influential period, consider my ultimate guide to Pop Art. Pop Art used collage to hold a mirror to society, transforming consumer culture into compelling artistic commentary. The dissolution of traditional artistic boundaries and an unparalleled expansion of materials truly blossomed after Pop Art's embrace of varied imagery, leading us into the boundless possibilities of today's mixed media.

The Contemporary Canvas: Mixed Media's Boundless Possibilities

And so we arrive at today, where collage, fueled by Pop Art's embrace of varied imagery, has blossomed into the vast, exciting world of mixed media. But what exactly is mixed media? Simply put, it's any artwork that uses more than one medium or material. This broad definition allows for an incredible range of expression, moving far beyond traditional painting or sculpture. It's no longer just paper; it's paint, ink, fabric, found objects, digital prints, discarded treasures – anything and everything can become part of the artistic tapestry. The possibilities feel truly endless, particularly with the widespread accessibility of printing technology, which has democratized the creation of layered artworks. For me, mixed media is about embracing layers – literal and metaphorical. It's about building a narrative, a feeling, or an abstract concept not just with color and form, but with the inherent textures and histories of the materials themselves. It’s about creating a dialogue between the smooth surface of paint and the rough edge of recycled cardboard, or the boldness of a drawn line and the subtle weave of textile. When I consider the archival quality of my work, I'm always thinking about the longevity of all these disparate materials, ensuring they will age gracefully together without degradation.

Physical Mixed Media: Boundless Materiality

Beyond the screen, the physicality of mixed media continues to expand. I remember once I found an old, faded piece of fabric that just felt like a memory, and it completely changed the direction of a painting, adding a layer of poignant history I hadn't planned. The scale of these works can vary immensely, from intimate, hand-held assemblages to monumental, room-filling installations, showcasing collage's incredible versatility. And sometimes, I think about found poetry, a literary parallel where writers select and reassemble words and phrases from existing texts to create new meanings – a collage of language, really. The process of culling, selecting, and recontextualizing fragments of language mirrors the visual artist's thoughtful choice of images and materials. This versatility isn't confined to fine art either; collage principles are ubiquitous, profoundly influencing everything from album cover art and book illustration (think Eric Carle's vibrant creations) to theatrical set design and film editing, where disparate visual elements (like montage sequences or layering visual effects) and auditory elements are brought together to create a cohesive narrative. It has also greatly impacted printmaking, where multiple plates, layering techniques, and found textures are often combined to create complex new compositions. You even see its influence in graphic design, where layered imagery, typography, and textures are combined to form compelling branding or editorial layouts, and in architecture and interior design, where different textures, materials, and historical elements are juxtaposed to create a new aesthetic. Its DIY aesthetic also lends itself perfectly to zines and independent publishing, offering an accessible way for counter-cultural movements to disseminate their messages.

Meanwhile, the concept of décollage, where instead of adding layers, existing layers are torn away to reveal what's underneath, offers a striking inverse of collage, often associated with artists like Mimmo Rotella and the Nouveaux Réalistes. This technique highlights that both addition and subtraction can create powerful visual stories by revealing the hidden history within a surface. Think of artists like Tony Cragg, who creates dynamic sculptures from found plastic objects, or the intricate, often grotesque, assemblages of Isa Genzken, which speak to consumer culture and urban decay. These artists, among many others, demonstrate the expansive potential of physical assemblage in contemporary art, extending collage beyond flat surfaces into three dimensions.

https://live.staticflickr.com/5788/23056316130_98a5297e4c_b.jpg, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0/

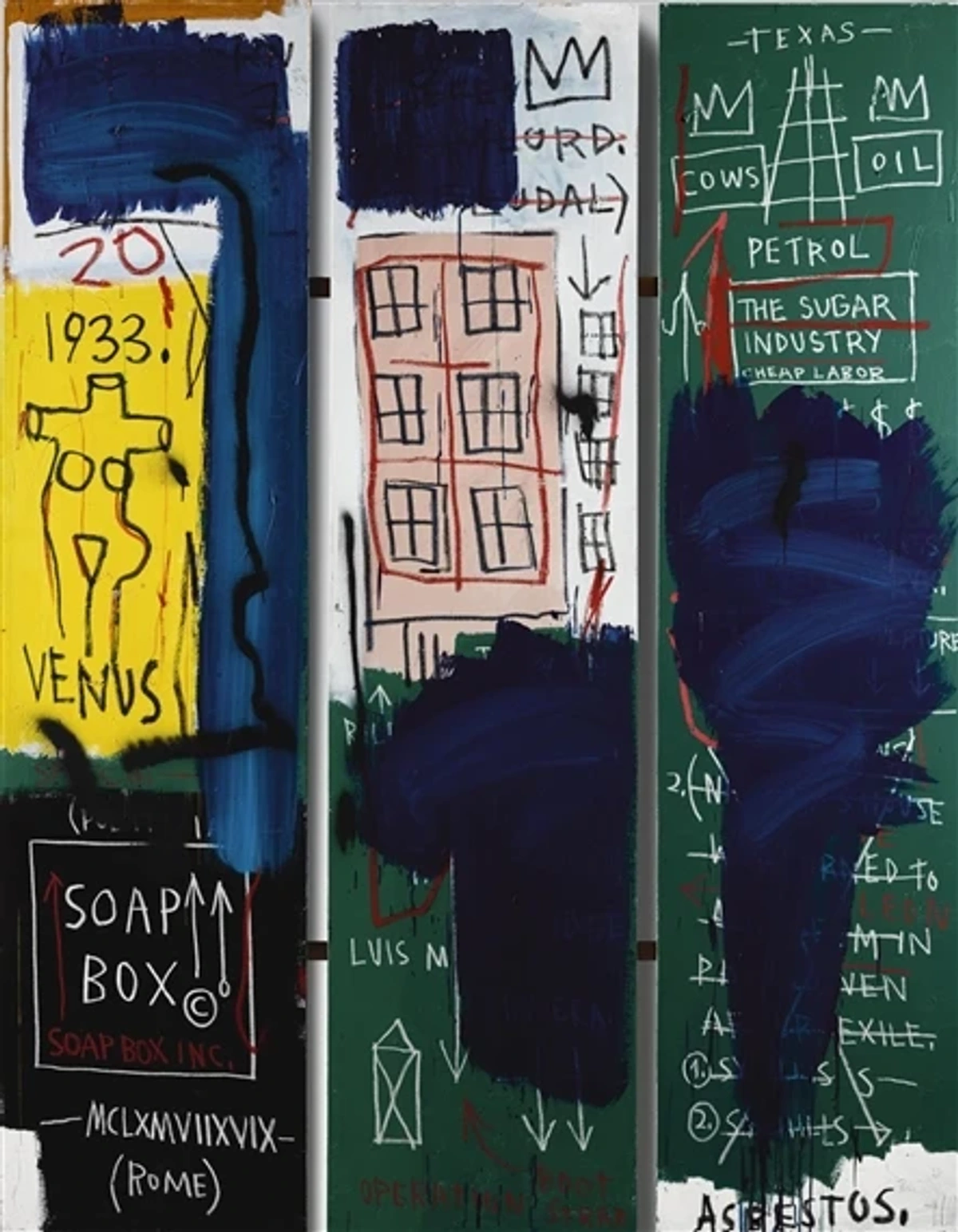

Jean-Michel Basquiat is a brilliant example of a contemporary master who transcended categories, blending graffiti, text, figures, and abstract marks into powerful mixed-media statements. His work is a raw, energetic testament to the power of combining elements to create something entirely new and profoundly impactful. Think of the powerful, often politically charged work of Wangechi Mutu, who combines magazine cutouts, medical illustrations, and African traditions to create surreal, compelling figures. Or Kara Walker, whose intricate cut-paper silhouettes, while not strictly 'glued' collages, certainly employ the art of assemblage and recontextualization to explore challenging historical narratives. Other contemporary artists like Nick Bantock, with his intricate, narrative-driven assemblages, or abstract digital artists like Casey Reas, who uses generative code to 'collage' visual elements, continue to expand collage's reach. The purpose in contemporary mixed media is incredibly varied, from personal expression and narrative building to social and political commentary, often embracing a multiplicity of meanings.

The Digital Frontier: Pixels and Possibilities

We've even seen the rise of digital collage, where artists manipulate pixels and layers on a screen using software like Photoshop, Procreate, Illustrator, or even browser-based tools, bringing the cut-and-paste ethos into the virtual realm with incredible precision or expressive freedom. Digital tools offer unparalleled ease of iteration and correction, precise control over placement and color through features like blending modes and digital brushes, and the ability to experiment rapidly with countless compositions or palettes without material waste. While they can sometimes lack the tactile satisfaction and unpredictable 'happy accidents' of physical materials, a clever digital artist can intentionally introduce these 'imperfections' – using textured brushes, employing random generators, or even embracing "glitches." This can evolve into complex forms like generative art, where algorithms create and combine images based on rules (think abstract patterns that grow and change, or dynamic landscapes composed of synthesized elements), or glitch art, which intentionally distorts digital imagery for aesthetic effect, leveraging digital 'breaks' as a form of visual assemblage (imagine distorted images or corrupted data made beautiful). Even AI-assisted compositions challenge our definition of authorship, using algorithms to 'cut' and 'paste' vast databases of images into new forms, blurring the lines between human and machine creativity. This often involves prompt engineering, where artists hone their textual commands to guide the AI in generating specific visual outcomes, effectively becoming curators of algorithmic creation. It's a wonderful, slightly overwhelming world out there, isn't it? So many tools, so many images – it sometimes feels like I'm drowning in possibility, endlessly scrolling through digital libraries or getting gloriously lost in layers. But that's part of the fun, right? This ease of creation begs a philosophical question though: does the democratized access to digital tools risk devaluing the labor and intention behind art, or does it simply open the floodgates to more diverse voices? It's a debate worth having.

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/b/b2/Untitled_Jean-Michel_Basquiat_.webp, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0

Navigating the Ethical Landscape: Appropriation and Copyright

Of course, this boundless freedom of contemporary collage also brings its own set of questions. When you're pulling from the vast ocean of existing imagery, you bump into concepts like appropriation and, yes, even copyright. It's a delicate dance, navigating the line between homage, critique, and creation, always asking: whose story am I telling, and with whose permission? What is an artist's ethical responsibility when transforming pre-existing works? Honestly, as an artist, this is a conversation I have with myself almost constantly when I'm reaching for that found image or that intriguing text fragment. Just last month, I found a gorgeous vintage advertisement, and for a moment, I wanted to use it directly, but then I paused, asking myself, "What new meaning will I add? Am I critiquing, or just reusing? Is this truly my voice, or am I just echoing another's?" It’s about being intentional, I think, and respectful of the original source, even while transforming it. Historically, artists from the Dadaists and Pop Artists were among the first to grapple directly with appropriation, using mass media images to provoke and critique society, long before formal legal frameworks caught up. Landmark cases like Rogers v. Koons (1992), while controversial, highlighted the complexities of fair use in art, prompting deeper scrutiny of how artists engage with copyrighted material.

Many artists navigate this by significantly transforming the source material, ensuring their new creation carries a distinct message, thus falling under the legal concept of transformative use. This simply means the new work has a distinctly different purpose or character from the original, adding new expression, meaning, or message. Think of it like this: taking a recognizable corporate logo or a fashion advertisement, then altering its colors, adding conflicting elements, and placing it within a critique of consumer culture, perhaps alongside imagery of environmental degradation. The original logo's commercial intent is fundamentally changed and recontextualized to convey a new, critical message. This often aligns with the legal principle of fair use in jurisdictions like the US, which permits limited use of copyrighted material without permission for purposes such as commentary, criticism, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, or research. It's a balance of public interest and creator rights. Moreover, collage has a long history in protest art and activism, with artists utilizing readily available imagery to create powerful, easily disseminated political posters and zines that challenge authority and spark dialogue. It's a crucial dialogue that challenges us to think about ownership, influence, and the very nature of creation in a world saturated with images.

If you're curious about diving deeper into this fascinating realm, I have a whole article dedicated to collage art and an extensive guide to mixed media in abstract art. For more on a specific master, explore the ultimate guide to Jean-Michel Basquiat. You can also peek into my own exploration of mixed media and how it shapes my abstract expression. Today, mixed media and digital collage push the boundaries of what art can be, celebrating infinite layers of meaning and material.

The Evolution of Collage: A Summary Across Eras

To summarize this incredible evolution and how each era approached collage, here's a quick overview:

Era | Core Approach to Collage | Key Materials/Mediums | Key Techniques | Purpose/Meaning | Key Characteristics | Key Artists |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cubism | Incorporation of real objects (papier collé) | Newsprint, wallpaper, fabric, oil paint, charcoal | Papier collé, fragmentation, deconstruction | Aesthetic exploration, challenging representation | Fragmented reality, multiple perspectives, tactile texture, influenced by non-Western art, challenging illusion | Picasso, Braque |

| Dada | Photomontage, assemblage of found objects | Newspaper, magazine cutouts, advertisements, photographs, found objects (rubbish) | Photomontage, layering, recontextualization, assemblage, manipulation of scale, grotesque juxtaposition | Political/social commentary, protest | Absurdity, satire, disruption of traditional values, anti-establishment, visceral protest against war, fractured reality, use of mass media for critique | Höch, Schwitters, Hausmann, Tzara |

| Surrealism | Juxtaposition of disparate images, automatic techniques | Victorian engravings, photographs, natural objects, paint, found texts | Juxtaposition, frottage, grattage, visual free association, automatic drawing, exquisite corpse | Psychological expression, tapping unconscious | Dreamlike, uncanny, emotional, explores inner mind, irrationality, direct access to subconscious, unsettling narratives, influenced by Freud | Ernst, Maar, Agar, Carrington, Man Ray |

| Pop Art | Use of mass media imagery, consumer items | Magazine ads, comic strips, celebrity photos, found objects, silkscreen, paint | Recontextualization, silkscreening (conceptual collage), assemblage, combine | Social commentary, critique of consumerism | Bold, graphic, ironic, blurs high/low art, celebrity culture, advertising, reflection of consumer society, visual language of commerce | Hamilton, Blake, Paolozzi, Rauschenberg, Warhol, Johns, Lichtenstein |

| Contemporary | Boundless mixed media, digital techniques | Paint, ink, fabric, found objects, digital prints, discarded treasures, code, pixels | Hybrid methods, digital manipulation (layers, blending modes), generative art, glitch art, décollage, AI-assisted | Personal narrative, social critique, ethical inquiry, authorship | Layers, diverse materials, digital manipulation, conceptual depth, addresses appropriation, hybrid approaches, expanding definitions of art, philosophical questions | Basquiat, Mutu, Walker, Reas, Cragg, Genzken |

FAQ: Your Collage Conundrums Answered

I know the world of collage can sometimes feel like a beautiful, bewildering maze. So, let's untangle a few common threads...

Is Collage “Real” Art?

Oh, the age-old question! My short answer: absolutely, unequivocally YES. For a long time, some in the art world (the ones who liked their art neat and predictable, I suppose) balked, dismissing it as mere craft or child's play. This dismissal often stemmed from a deeply ingrained academic tradition that prioritized meticulous skill in rendering, seamless illusion, and the artist's singular hand, seeing collage's use of 'found' or 'mundane' materials as inherently less artistic or even a shortcut. It directly challenged the established hierarchy of art forms and the definition of what constituted artistic labor. But history, with its beautiful habit of proving the rebels right, quickly demonstrated collage’s profound capacity for expression. Its inherent artistic merit lies in its ability to transform the mundane into the profound, creating new narratives and challenging perceptions through thoughtful juxtaposition and recontextualization – a fundamental artistic act akin to metaphor in literature. Pioneering exhibitions at institutions like the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, which championed Cubist collage early on, and influential European galleries like those of Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, helped solidify its place in the canon. Critics like Clement Greenberg, while sometimes controversial, acknowledged its formal innovations, further cementing its status. It challenges perceptions, provokes thought, and can be as technically demanding and conceptually rich as any other art form, offering deep conceptual depth and emotional resonance. The revolutionary use of mundane materials, once seen as an affront, became a testament to art's ability to transform the everyday into the profound. And beyond fine art, collage's principles have profoundly influenced graphic design, book illustration (like Eric Carle's vibrant, layered creations), advertising, and even film editing, where disparate visual and auditory elements are brought together to create a cohesive narrative. It's truly a testament to how boundary-pushing ideas often become the foundation of new traditions.

How Can I Start with Collage?

Just start! Honestly, that’s the best advice for any creative endeavor. Gather some old magazines (look for interesting textures, bold headlines, intriguing portraits, or unexpected color palettes – vintage fashion magazines offer striking aesthetics, scientific journals provide technical imagery and diagrams, old maps or book pages add texture and narrative depth, while gardening or home decor magazines can be great for natural elements or patterned backgrounds), newspapers, discarded photos, fabric scraps, or any other textured papers (like handmade paper, tissue paper, or sandpaper for texture). Scissors, a good quality PVA glue (archival PVA is great for longevity for paper-based collages and prevents yellowing and degradation), or a reliable spray adhesive for larger, flatter areas, and perhaps a craft knife and self-healing cutting mat are your basic tools. Don't worry about perfection; focus on play. Remember to opt for acid-free materials if you want your creations to last without yellowing or degradation over time.

Experiment with tearing versus cutting, layering, juxtaposing unexpected images, or even trying techniques like décollage (ripping away existing layers to reveal buried imagery, often by layering posters and then tearing parts away) or transfer techniques (using a medium like gel to lift an image from one printed surface and adhere it to another, creating a unique, often distressed look). Maybe start with a simple theme: 'chaos and calm,' 'a day in my life,' 'found narratives from old books,' or 'urban textures' and just see what jumps out at you. The beauty of collage is its accessibility and the freedom it offers. It's a wonderful way to explore different visual languages, and honestly, to simply have some fun. My own journey often starts with a single image or color that sparks an idea, and then I just let the materials lead the way.

How Do I Preserve My Collage Artworks?

Preservation is key if you want your collages to last! The most important step is to use archival-quality materials from the start: acid-free papers, glues, and paints. Acid-free PVA glue is excellent for paper-based collages, as it won't yellow or degrade over time. If you're using found objects, consider if they are stable; some materials (like certain plastics or decaying organic matter) can degrade and damage surrounding elements. A good quality UV-protective spray varnish or fixative can protect against fading from light exposure. For framing, always choose acid-free mats and backing boards and, ideally, UV-filtering glass or acrylic to prevent environmental damage. Storing collages flat in archival boxes, away from extreme temperatures, humidity, and direct sunlight, will also significantly extend their lifespan. Think of your finished collage as a precious artifact – you want it to tell its story for generations! And if your artwork heavily utilizes appropriation, consider documenting your process or original sources for ethical and historical transparency.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Creation_Of_The_Mountains.jpg, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.en

The Next Layer: My Continuing Exploration

The history of collage is a testament to human creativity and our endless desire to make sense of, or even intentionally disrupt, our surroundings. From Picasso’s daring newspaper fragments to Basquiat’s layered urban poetry, collage has always been about reinvention, about finding beauty and meaning in the unexpected assembly of things. It’s a powerful reminder that art can transform the mundane into the profound, and that our stories are often best told in fragments brought together with intention, reflecting the fragmented yet interconnected nature of modern life itself. It's a continuous, evolving narrative, much like my own artistic journey.

For me, there's something incredibly liberating about collage. It’s an exercise in relinquishing control, a dance between intention and accident. You might start with a clear idea, but the materials often have other plans. A torn edge might suggest a new horizon; a random image might spark an unexpected narrative. Those "happy accidents" are sometimes the best part, aren't they? It’s a constant process of discovery. It’s a wonderful, messy parallel to life itself, trying to fit all the broken pieces, the beautiful scraps, into a narrative that feels authentically you. I often feel this when I'm wrestling with a new canvas; the initial chaos, the doubt, then that moment when disparate elements finally click into place. This embrace of the unexpected, this willingness to let the materials guide me, is fundamental to how I approach all my art, from painting to sculpture, and even extends to how I think about graphic design and film editing, where disparate elements are brought together to create a cohesive vision.

My own artistic journey continues to be shaped by this spirit of discovery, and you can see glimpses of it in my artist timeline. Who knows what I'll cut and paste next? Perhaps a piece reflecting the vibrant energy of my museum in 's-Hertogenbosch, or a new series inspired by the very act of reassembly that you can find among the art for sale on my website. Thank you for joining me on this exploration. I hope it sparked some thoughts and maybe even inspired you to pick up some scissors and glue yourself! What fragments of your own life are waiting to be brought together to create something new, a testament to your own unique story?