Finding Humor in Contemporary Art: An Artist's Engaging Guide to Witty Works

Explore the surprising role of humor in contemporary art. An artist shares personal insights, delves into satirical, absurd, and witty works, and explains why laughter is a powerful tool in the art world.

The Unexpected Chuckle: Finding Humor in Contemporary Art

You know, for the longest time, I thought art was supposed to be serious. Like, capital 'S' Serious. You walk into a gallery, you put on your most thoughtful face, you nod sagely at canvases, and you definitely don't laugh. Laughter felt... disrespectful, somehow. Like you weren't taking the artist's profound message seriously enough. It felt like breaking some unwritten rule of the art world.

I remember one time, years ago, walking into a minimalist exhibition. Everything was stark white, clean lines, silent reverence. I was trying my best to feel something deep and meaningful, nodding along with the hushed whispers of other visitors. Then I saw it – a single, perfectly placed banana duct-taped to the wall. My brain did a double-take. Was it a statement? A critique? Or... was it just funny? A genuine, unexpected chuckle escaped before I could stop it. The immediate internal conflict – Is this allowed? Is this art? – was almost as interesting as the piece itself. And that's when I started to realize art didn't always have to be solemn. It could be a conversation, a shared moment, even a laugh. That moment, honestly, felt like a secret handshake, a quiet rebellion against the perceived stuffiness of the art world.

Yes, my friend. It absolutely is allowed. Humor in contemporary art isn't just allowed; it's a powerful tool, a sharp critique, a moment of connection, or sometimes, just a glorious, intentional joke.

Why So Serious? Breaking Down the Art World's Stiff Upper Lip

Why does the art world often feel so... intimidating? Let's be honest, it does. There's jargon, history, and a whole lot of discussion about meaning. When you're trying to figure out what is modern art or contemporary art meaning, adding humor into the mix can feel like a curveball. It certainly felt that way for me. Like I wasn't smart enough to 'get' the serious stuff, and the funny stuff must surely be a trick. Maybe you've felt that too?

This idea that 'serious' art must be devoid of humor isn't new. It often stems from academic traditions that valued gravitas and profound themes, or perhaps the rise of movements like Abstract Expressionism, which were often presented with intense intellectual weight. The art market, too, can sometimes seem to value solemnity over wit, equating seriousness with importance and, well, higher prices. It's like there's an unwritten rule that if you're not frowning thoughtfully, you're not truly appreciating the work. But I think that misses a huge part of what art can be.

Think about it: humor is fundamentally human. It's how we cope, how we connect, how we point out the ridiculousness of the world. Why wouldn't artists, who are often holding a mirror up to society (or sometimes, just holding a banana to a wall), use one of our most basic forms of communication? It's a way to cut through the noise, to disarm the viewer, and to make a point that might otherwise be too heavy or confrontational.

For me, encountering humor in art is like finding a secret handshake. It breaks down that wall of 'seriousness' and invites you in. It says, 'Hey, I see the absurdity too. Let's share a moment about it.' It makes the art feel less like an untouchable artifact and more like a conversation. It's a way to connect with the work on a different, perhaps more immediate, level. This isn't a new phenomenon; artists have been using wit and satire for centuries. Let's look at where this lighter side of art comes from.

A Brief History of Art's Lighter Side

Holding a mirror up to society, or just holding a banana to a wall... artists have been using wit, satire, and playful subversion for centuries. It's not a new phenomenon, just one that has evolved dramatically. Exploring this history felt, for me, like uncovering a hidden lineage of rebels and pranksters within the grand narrative of art.

Think of the biting social critiques embedded in the works of artists like William Hogarth in the 18th century. His print series like Beer Street and Gin Lane used exaggerated, often grotesque, caricatures to mock the societal ills brought on by excessive drinking. The humor here is sharp, moralistic, and aimed squarely at the viewer's conscience – a direct ancestor of today's satirical art.

Or consider the dark, often grotesque humor found in some of Francisco Goya's prints, particularly his Caprichos series. These works satirized the follies and superstitions of Spanish society with a sharp, sometimes disturbing, wit. Goya's willingness to expose the uncomfortable through caricature resonates deeply in contemporary art that uses humor to tackle difficult truths. It's humor that makes you squirm a little, but also makes you think.

The early 20th-century movements like Dada and Surrealism really amplified the use of absurdity and playful disruption as core artistic strategies. Dada artists, reacting to the horrors of World War War I, embraced nonsense and anti-art gestures. Think of Marcel Duchamp's Fountain, a urinal signed 'R. Mutt'. Was it a serious philosophical statement about authorship and readymades? Absolutely. Was it also a giant, cheeky middle finger to the establishment that was inherently funny in its audacity? You bet. Discovering Dada felt like permission to question everything, often with a smirk. Dada paved the way for art that didn't take itself too seriously, even when making profound points, a spirit very much alive in contemporary humorous art.

![]()

Surrealism, while often delving into the subconscious and dreams, frequently employed juxtaposition and unexpected imagery for humorous effect. René Magritte's pipe that isn't a pipe (The Treachery of Images) or his men raining from the sky (Golconda) are visually witty, playing with logic and expectation. Salvador Dalí's melting clocks (The Persistence of Memory) are iconic surrealism, but there's an undeniable absurdity, a visual joke about the fluidity of time and reality. This surrealist playfulness with reality and expectation is a key ingredient in much contemporary humorous art.

Moving into the mid-20th century, Pop Art embraced mass culture with a wink and a nudge. Andy Warhol's soup cans and celebrity portraits, while commenting on consumerism and fame, have a deadpan, repetitive quality that can be seen as a form of visual humor or irony. Roy Lichtenstein's comic strip panels (Whaam!, Drowning Girl) take low-brow source material and elevate it, often highlighting the melodrama and clichés with a sense of playful detachment. Pop Art's use of irony and appropriation directly influences contemporary artists who comment on media and consumer culture through humor.

Even movements like Fluxus in the 1960s and 70s, with their emphasis on performance, events, and everyday objects, often incorporated elements of chance, playfulness, and absurdity that elicited smiles, confusion, and sometimes outright laughter. It was about breaking down the barriers between art and life, often in delightfully unexpected ways, a legacy seen in contemporary performance and conceptual art that uses humor.

The Many Faces of Funny: Types of Humor in Contemporary Art

So, how does humor manifest in the art we see today? It's not just about a banana on a wall (though that certainly fits!). Contemporary artists use a vast palette of comedic approaches, often blending them in unexpected ways. It's like they have a whole new set of colors on their palette, but instead of pigment, it's punchlines and visual gags.

- Satire and Social Critique: This is a classic, tracing back to Hogarth and Goya. Artists use humor to point out the absurdities, injustices, and hypocrisies of society, politics, or the art world itself. It can be biting, subtle, or laugh-out-loud ridiculous. Example: A sculpture of a politician with exaggerated features, mocking their policies, or a painting mimicking a corporate logo to critique consumerism. The humor comes from recognizing the target and the artist's clever jab.

- Absurdity and Nonsense: Echoing Dada and Surrealism, sometimes the humor comes from a complete lack of logic or meaning, pushing boundaries to the point of delightful confusion. This can challenge our expectations of what art should be or mean. Example: A video of someone performing a repetitive, nonsensical task for an extended period, or a sculpture of a melting teapot pouring sand. It's funny because it defies rational explanation.

- Irony and Sarcasm: Saying one thing and meaning another, or presenting something seriously that is clearly ridiculous. This requires the viewer to 'get' the disconnect, creating a shared moment of understanding (and often, a smirk). Pop Art often used this. Example: A painting that meticulously imitates a kitschy style but depicts a mundane or unsettling subject, or a series of seemingly earnest instructional drawings for impossible tasks. The humor is in the gap between appearance and intent.

- Visual Puns and Wordplay: Clever use of imagery or text to create a double meaning or a visual joke. This can be simple and direct or layered and complex. Example: A sculpture shaped like a common object but made from an unexpected material, creating a visual pun (like a fork made of forks), or an artwork incorporating text that plays on words related to the image. It's the visual equivalent of a dad joke, but often much smarter.

- Slapstick and Physical Comedy: Less common in traditional mediums, but can appear in performance art or video, using exaggerated actions or situations for comedic effect. Drawing on Fluxus traditions, this type of humor is often about the artist's body or interaction with objects. Example: A performance piece involving clumsy movements or exaggerated facial expressions, or a video installation where objects behave in unexpectedly silly ways. It's the art world's version of tripping over your own feet.

- Conceptual Jokes: The humor lies not in the visual object itself, but in the idea or concept behind it. The banana on the wall is a prime example – the humor is in the gesture, the context of the gallery, and the implications for the art market. This is a direct descendant of Conceptual Art and Fluxus. Example: An artwork consisting solely of a lengthy, overly complicated set of instructions for a simple action, or a piece where the title is the punchline. It's the art equivalent of a shaggy dog story.

- Self-Deprecating Humor: Artists turning the joke on themselves, their process, or the perceived pretentiousness of the art world. This can be incredibly disarming and relatable. Example: A painting that includes text like "I spent three months on this and it's still terrible", or a performance piece where the artist highlights their own failures or awkwardness. It's the artist saying, "Yeah, I know this is weird, but aren't we all?"

It's often a mix of these. An artist might use absurdity to make a satirical point, or irony to highlight a conceptual joke. The beauty is in the unexpected combination, the moment you realize the artist isn't just making something, they're telling you something, often with a wink.

Humor also manifests differently depending on the medium. In performance art, timing, interaction with the audience, and the artist's physical presence are key to comedic effect. Video art can use editing, sound, and juxtaposition to create visual gags or build narrative absurdity. Installation art might use scale, unexpected materials, or placement within a space to create a humorous environment or situation. Each medium offers unique possibilities for a chuckle.

Contemporary Artists Who Master the Chuckle

Ready to meet some artists who aren't afraid to make you laugh (or at least smirk)? Beyond the historical figures, many artists working today wield humor with incredible skill. Here are just a few examples, and some specific pieces that might make you smile, or at least think with a smirk:

- Maurizio Cattelan: The king of controversial, often hilarious, interventions. His work frequently critiques the art market and societal values through absurdity and shock. La Nona Ora (The Ninth Hour, 1999), depicting Pope John Paul II struck down by a meteorite, uses dark, absurd humor to comment on the vulnerability of even the most powerful figures. And of course, Comedian (2019), the banana duct-taped to a wall, is a masterclass in conceptual humor, sparking global debate and countless memes, highlighting the absurdity of the art market itself. It's the kind of piece that makes you groan and laugh at the same time.

- Sarah Lucas: Known for her provocative and witty sculptures using everyday objects, particularly furniture, tights, and cigarettes, to explore themes of gender, sexuality, and the body. Her work is often raw, direct, and uses a blunt, sometimes dark, humor that is both challenging and funny. Pieces like Two Fried Eggs and a Kebab (1992), using a table and food items to represent a reclining nude, are visually crude and humorous, directly confronting societal views on the body with a defiant wink. It's humor that makes you blush a little.

- Martin Creed: His work often involves simple, conceptual gestures that can be seen as playful or absurd, questioning the definition of art itself. Work No. 11 (1994), a crumpled ball of paper, or Work No. 227: The lights going on and off (2000), where lights in a gallery simply turn on and off at five-second intervals, are examples where the humor lies in the minimalist execution of a seemingly pointless action or object, prompting questions about value, meaning, and the viewer's own expectations with a deadpan delivery. It's the art world equivalent of watching paint dry, but somehow funnier.

- David Shrigley: His drawings, sculptures, and animations are instantly recognizable for their simple, often crude style and darkly humorous, often existential, captions or themes. He finds humor in the mundane, the awkward, and the slightly disturbing aspects of life. A drawing of a potato with the caption "Potato" is a simple visual pun and conceptual joke. His sculpture Thumbs Up (2016), a giant bronze thumb, is an absurdly monumental take on a casual gesture, blending the everyday with the traditionally heroic scale of public sculpture for humorous effect. Shrigley's work often feels like the funniest, most depressing doodle you've ever seen.

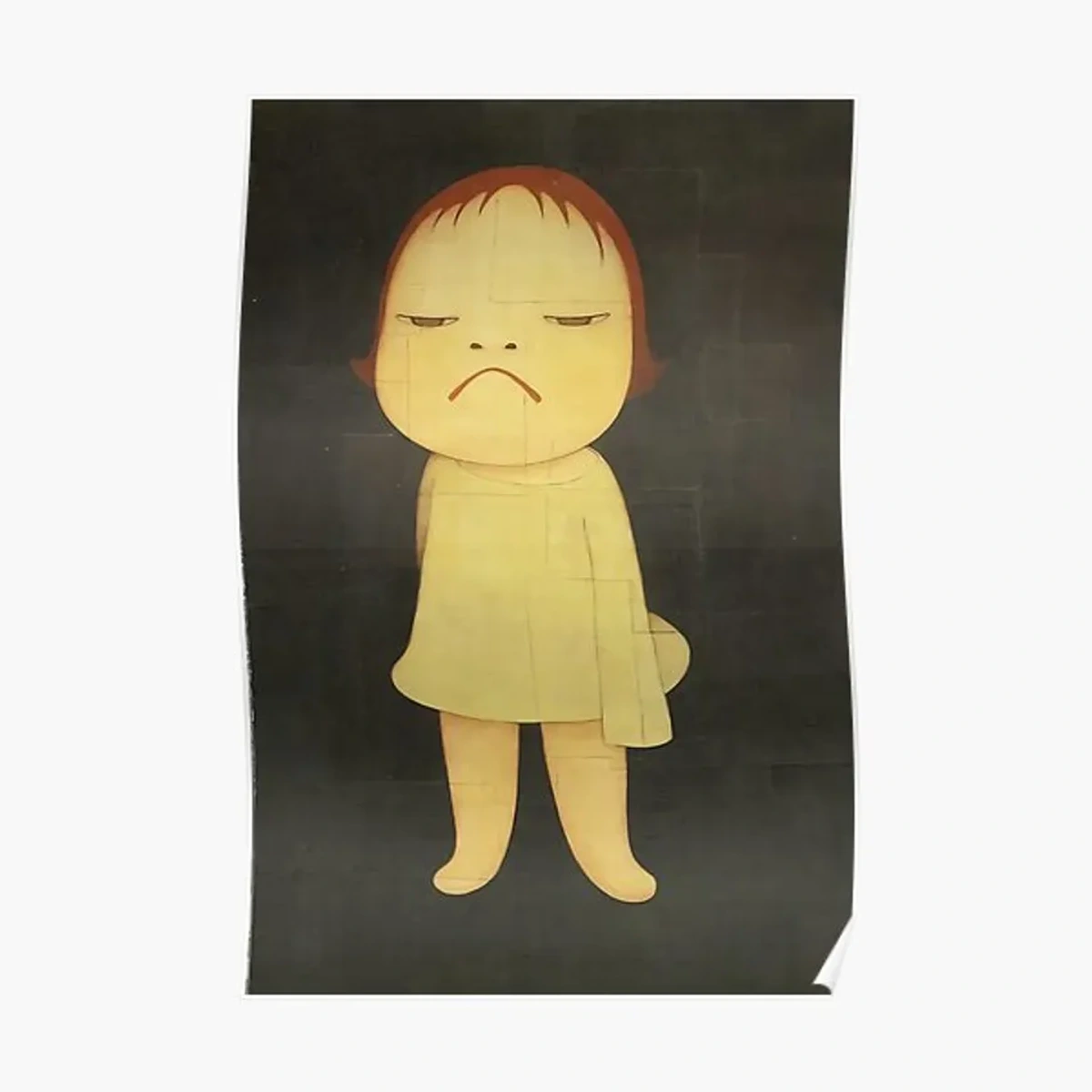

- Yoshitomo Nara: While his images of wide-eyed, sometimes slightly menacing children and animals might seem cute at first glance, there's often an underlying layer of dark humor, rebellion, or loneliness that resonates deeply. The humor is subtle, often stemming from the unexpected juxtaposition of innocence and attitude. His iconic angry or defiant children, like the one in The Little Pilgrim (Night Walking) (1999), often carry a quiet, rebellious humor that challenges expectations of childhood innocence. It's the kind of humor that makes you chuckle and then feel a little pang.

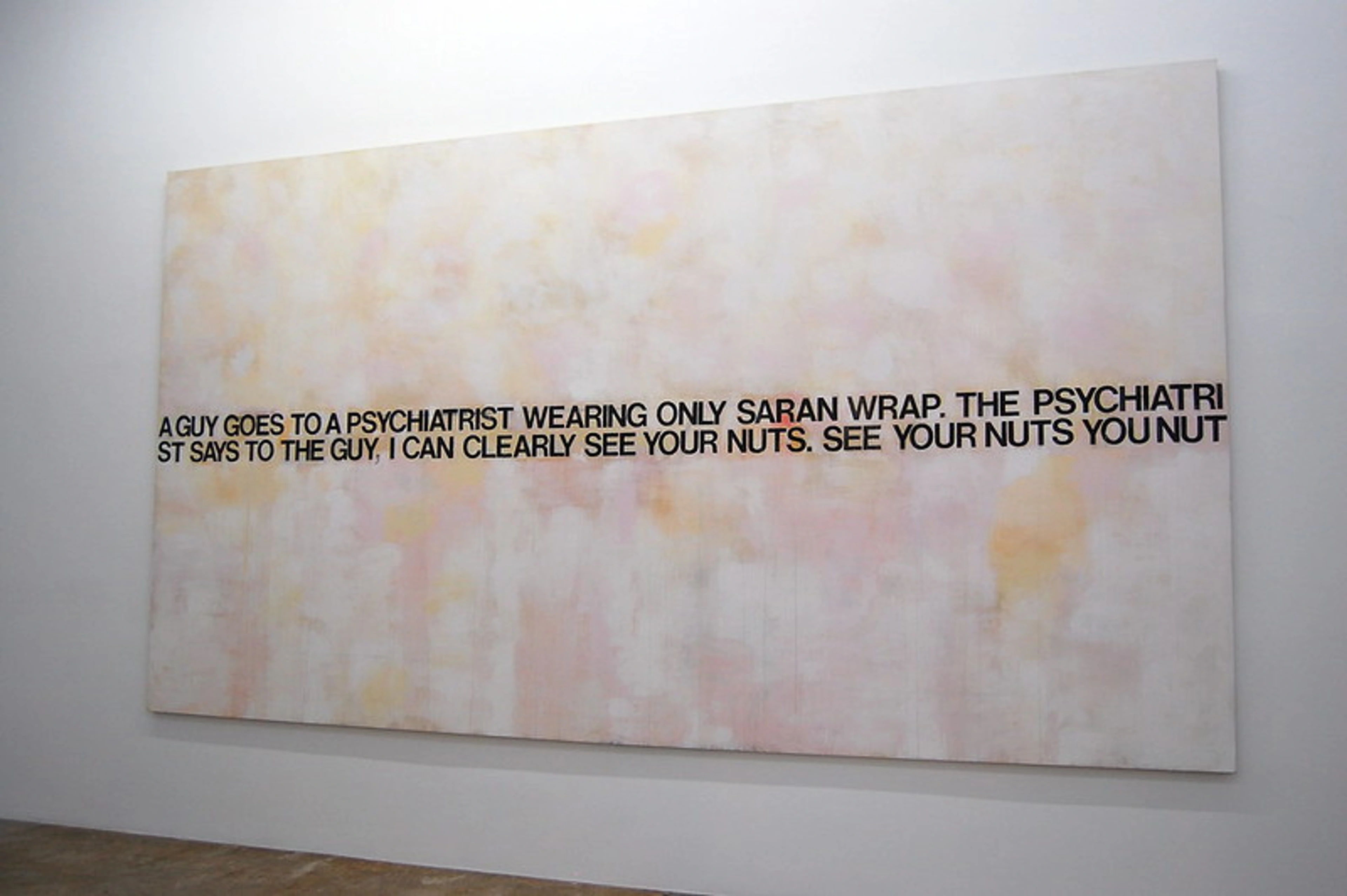

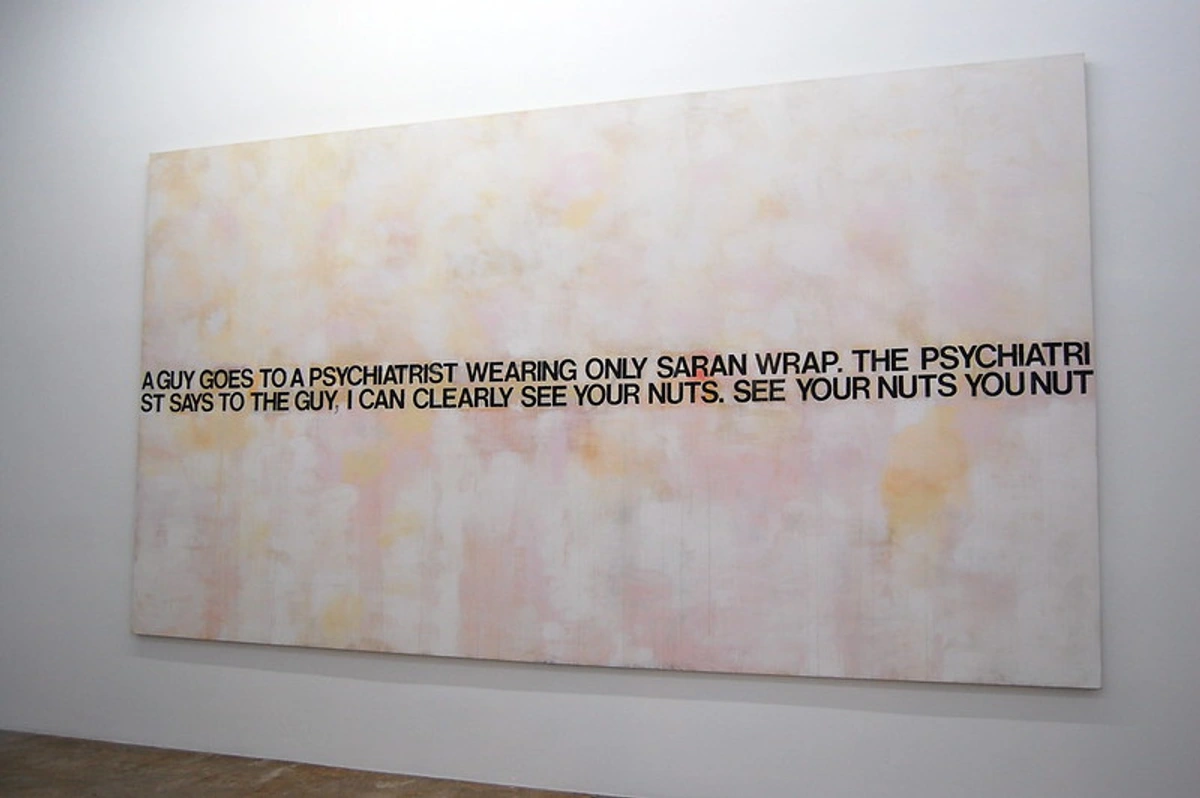

- Richard Prince: Known for his controversial use of appropriation, particularly re-photographing advertisements. His Joke Paintings, which feature printed jokes on canvas, use conceptual humor and irony to comment on authorship, mass culture, and the art market itself. The humor is often dry, even uncomfortable, forcing the viewer to confront the context of the joke within the high-art setting. It's humor that makes you question who's really laughing.

- Banksy: While primarily known for street art and social commentary, Banksy frequently employs satire and visual puns with a sharp, often humorous edge. His stencils often place unexpected images in public spaces to create witty or critical statements, like the image of two policemen kissing (Kissing Coppers, 2004) or the girl with the balloon being pulled away (Girl With Balloon, 2002), which, while poignant, also has an element of visual absurdity. It's humor with a message, delivered with a spray can.

- John Baldessari: A pioneer of Conceptual Art, Baldessari often used text and image juxtaposition for witty and ironic effect. His work frequently pointed out the absurdities of art-making and interpretation. Pieces like I Will Not Make Any More Boring Art (1971), written repeatedly on a gallery wall, or his photo-text works that combine seemingly unrelated images and captions, are prime examples of his dry, intellectual humor. It's humor that makes you think, and then maybe chuckle at the thought.

The Power and Reception of Humorous Art

So, why do artists bother with humor? It's more than just getting a cheap laugh. Humor can be incredibly effective, and for me, it's a vital part of connecting with an audience. It's a tool I try to use in my own work, finding that balance between depth and approachability.

- It Disarms: Laughter is a natural human response that lowers defenses. A humorous artwork can make a viewer more open to a difficult or challenging message than a purely serious one might. It breaks the ice.

- It Creates Connection: Sharing a laugh, even with an artwork, creates a bond. It makes the viewer feel like they are 'in on the joke' with the artist, fostering a sense of understanding and accessibility. It's that secret handshake again.

- It Makes the Uncomfortable Accessible: Satire and dark humor can allow artists to tackle sensitive or taboo subjects in a way that is thought-provoking without being overly preachy or alienating. It's the spoonful of sugar that helps the medicine go down.

- It Challenges Authority: Humor, especially satire, has a long history of punching up. It can effectively critique power structures, institutions (including the art world itself), and societal norms in a way that is memorable and shareable. It's a gentle (or not so gentle) nudge to the status quo.

- It's Memorable: Let's be honest, you're probably going to remember the banana duct-taped to the wall longer than a beige abstract painting (unless that painting is also somehow funny). Humor makes art stick in your brain, creating a lasting impression.

However, humorous art isn't always met with open arms. Some critics and viewers dismiss it as lightweight, not 'serious' enough to be considered important art. They might argue it lacks technical skill, or that the humor distracts from deeper meaning. There's often a debate about its longevity or its place in the market compared to more traditionally solemn works. This brings us back to that initial feeling I had in the gallery – the internal conflict about whether laughter belongs. Perhaps some people are simply uncomfortable with not knowing how to react – is it okay to laugh? Am I supposed to be thinking something profound instead? But perhaps that conflict is part of the point. Humorous art forces us to question our own preconceived notions about what art should be and how we should react to it. It challenges the viewer as much as it challenges the art world itself.

Finding Your Own Chuckle in the Gallery

Next time you find yourself in a gallery or museum, maybe looking at some famous contemporary art or exploring contemporary art galleries in Europe, try looking for the humor. Don't feel pressured to maintain a solemn face. Look for the unexpected juxtapositions, the subtle ironies, the outright visual gags, or the conceptual winks. Look for the pieces that make you pause, maybe tilt your head, and then perhaps, just perhaps, let out an unexpected chuckle.

It's okay to laugh. It doesn't mean you're not taking the art seriously. Sometimes, it means you're finally getting it on a deeper, more human level. And who knows, maybe that connection will inspire you to explore art further, perhaps even find a piece that brings a smile to your own walls. You can always buy art that speaks to you, whether it's funny or not. My own artist's journey has certainly been filled with unexpected moments of levity, and I try to bring that into my own work, available for sale or seen in places like my museum in Den Bosch.

So go on, seek out the chuckle. The art world might just surprise you.